In this issue of Blood, Roger and colleagues present data on the magnitude of influence that broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitors exert on TLR-driven immune responses, thus demonstrating that HDAC inhibitors are immunosuppressive drugs.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have become promising candidates for the treatment of different types of cancer. “At least 80 clinical trials are under way, testing more than eleven different HDAC inhibitory agents,”1p1 for their antitumor effect in hematologic and solid malignancies. The HDAC inhibitor vorinostat is now an approved add-on therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2 HDAC inhibitors induce growth arrest, differentiation, and programmed cell death, and inhibit invasion and angiogenesis. However, over the years, evidence has accumulated showing that HDAC inhibitors also have immunomodulatory activity even in nonapoptotic concentrations. Although HDAC inhibitors increase acetylation of histones, a condition associated with increased transcriptional accessibility, multiple reports have shown that HDAC inhibitors possess suppressive effects on immune response gene induction. Individual cytokines that are induced by microbial components triggering Toll-like receptors (TLRs) were reported to be inhibited by HDAC inhibitors.3-5 Yet, the extent of those inhibitory effects and possible functional consequences during infections were largely unknown.

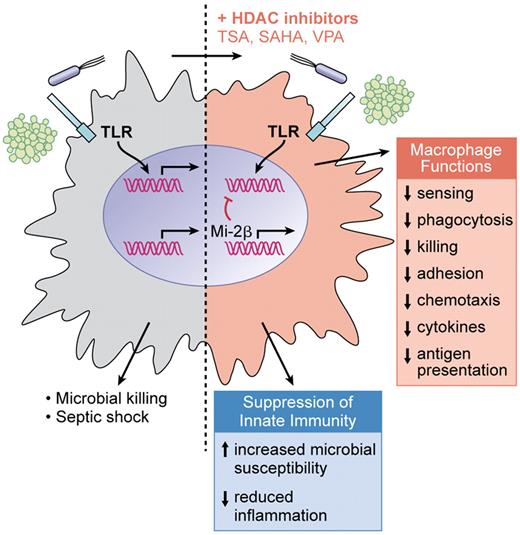

Addition of broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitors to macrophages stimulated through TLRs results in a dominant inhibition of gene expression (up to 60% of TLR-induced genes) encompassing suppression of all major functions of macrophages. Consequently, in vivo susceptibility to infections is increased when the HDAC inhibitor valproate is administered to mice, whereas overreactivity of innate immunity as observed in septic shock is decreased. (Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.)

Addition of broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitors to macrophages stimulated through TLRs results in a dominant inhibition of gene expression (up to 60% of TLR-induced genes) encompassing suppression of all major functions of macrophages. Consequently, in vivo susceptibility to infections is increased when the HDAC inhibitor valproate is administered to mice, whereas overreactivity of innate immunity as observed in septic shock is decreased. (Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.)

In this issue, Roger et al used genome-wide expression profiling to study global alteration of TLR-induced gene induction by HDACs in macrophages.6 Surprisingly, up to 60% of genes transcriptionally increased by TLR2 or TLR4 stimulation were inhibited in the presence of the broad-range HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A, whereas only 16% of genes were potentiated. Gene activity that was inhibited included all major functions of activated macrophages, such as microbial sensing by pattern-recognition receptors, signal-transduction mediators, transcription regulators, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and costimulatory molecules. Thus, this work unexpectedly found that HDAC inhibitors were mostly immunosuppressive.

Of note, these results find their counterpart in vivo: treatment of mice with the HDAC inhibitor valproate increased the susceptibility to develop pneumonia by Klebsiella pneumoniae or systemic candidiasis. Conversely, HDAC inhibition conferred protection in models of septic shock by limiting the cytokine burst. Corroborating these observations, it has been reported previously that patients treated with HDAC inhibitors show an increased susceptibility to develop severe infection even without neutropenia.7 Inhibiting cytokine activity is also known to affect microbial susceptibility in studies using tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition. Thus, within the ongoing HDAC inhibitor trials attention should be paid to infectious susceptibility. The protective effect of HDAC inhibitors on dysregulated inflammation offers a potential therapeutic intervention in the treatment of sepsis. Of note, and taking into account the link between chronic inflammation and cancer, one might wonder whether part of the therapeutic activity of HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapies is due to the pronounced inhibition of inflammation.8

Defining the mode of action of HDAC inhibitors on the immune system is clearly needed, yet so far only poorly understood. The article by Roger et al suggests a novel activity of HDAC inhibitors, that is induction of the chromatin modifier Mi-2β. Enhanced promoter recruitment of Mi-2β to the interleukin 6 (IL-6) promoter is followed by inhibition of IL-6 transcription. Mi-2 is part of the nucleosome remodeling, histone deacetylation (NuRD) complex. Mi-2β/NuRD acts antagonistically to the SWI/SNF nucleosome-remodeling complex and inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced cytokine production in macrophages and dendritic cells.9 In accordance with its role as remodeling suppressor, genes known to be dependent on initial nucleosome remodeling—as exemplified by IL12p40 and IL6—are specifically affected by HDAC inhibitors, whereas expression of “primary” genes with an open promoter conformation (for example, TNF) is less inhibited on TLR stimulation. This might indicate that very directly hard-wired genes can still be induced in HDAC inhibitor–treated cells, thus limiting the magnitude of innate immune suppression. The selective block of nuclear remodeling and modification of accessibility of promoter regions by HDAC inhibitor–induced Mi-2β/NuRD may also explain the inhibition of cytokine expression on the level of transcription factor binding without affecting upstream signal transduction (nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation), an observation that had previously been made. However, the results presented in this issue do not exclude that additional mechanisms (for example, increased acetylation of transcription factors) participate in the modifying effects, as Mi-2β has only been studied in detail for IL-6 and differing results for TNF have been published.

In contrast to previous reports,3 prolonged Stat1 tyrosine phosphorylation and increased IFNβ expression are novel observations. However, inconsistent with increased IFNβ/Stat1 activation, IFNβ-dependent genes in general are suppressed. Furthermore, Stat1 itself can be acetylated, resulting in an enhanced dephosphorylation.10 Timing of HDAC inhibitor administration and microbial stimulation might be a decisive variable.

Taking into account that Trichostatin A (TSA) inhibits up to 11 different HDACs with striking differences in substrate specificity to histone and nonhistone proteins, the question of contribution of individual HDACs toward the immune-suppressive effect of HDAC inhibitors arises. Today, several more or less isoform-specific HDAC inhibitors are available. The next step would be to focus on isoform-specific inhibitors and to test their effects on inhibition (dominating with TSA) or activation of immune responses. One study claims that inhibition of HDAC1/2 indeed results in an induction instead of inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines.11 In the end, this report confirms and strengthens the notion of HDAC inhibitors as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■