Abstract

Since the National Institutes of Health Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease (cGVHD) Consensus Project in 2005, a need has emerged to evaluate cGVHD more methodically, not only to make a cGVHD diagnosis, but also to accurately classify individual organ and global organ severity, at baseline and in follow-up so that subjects participating in clinical trials may reliably be assigned an accurate response category irrespective of the evaluator. Even for patients not enrolled on a clinical trial, periodic complete cGVHD assessments can allow subtle manifestations to be detected, monitored carefully, and/or treated early with the goal of hopefully avoiding progression to highly morbid, difficult to treat, and quite often irreversible forms of cGVHD. Early feedback has been that the National Institutes of Health approach to diagnosis classification, staging, and response, as well as other new assessment tools, are too detailed and overly complex. This article tries to address many of these issues by describing how I conduct a comprehensive cGVHD assessment using a streamlined and reliable method that I use regularly within the constraints of a busy clinic.

Introduction

Major changes in the diagnosis, classification, and response evaluation of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) were suggested in several position papers by the Working Groups of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference in Clinical Trials in cGVHD conducted in 2005.1-4 By necessity, as the field moves toward validating these approaches, there has emerged a need to evaluate patients more methodically, not only to make a cGVHD diagnosis, but also to accurately classify individual organ and global organ severity, at baseline and in follow-up, so that subjects participating in clinical trials may reliably be assigned an accurate response category irrespective of the evaluator.

The ongoing “0801” cGVHD intervention trial5 of the Blood and Marrow Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) has embraced these new principles, but early feedback has been that the detail and complexity of the new diagnosis, classification, and response assessment fit poorly within the constraints of a busy clinic. In this article, I propose a streamlined reliable method for completing a comprehensive cGVHD assessment, which takes ∼ 17 minutes, comparable or shorter in duration to a full clinical neurologic examination. The entire approach is also demonstrated in a 30-minute instructional video (http://www.fhcrc.org/science/clinical/gvhd/)6 together with the cGVHD Provider Survey. In my own clinical practice, even for patients not enrolled on a clinical trial, I have learned that it is essential to periodically perform complete cGVHD assessments to avoid missing subtle early signs, which, if undetected, may progress to highly morbid, difficult to treat, and quite often irreversible forms of cGVHD.

Since the initial description of chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) in the 1980s, countless publications have presented outcomes data based on the dogma that cGVHD occurs only after day 100 and that its severity is simply “limited” or “extensive” based on the number of organs involved rather that the severity of manifestations within organs.7 This dichotomous classification has been replaced by a schema that rates individual and global organ severity as none (score 0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), based on the degree to which organ involvement negatively affects a patient's activities of daily living.1 For example, severe isolated oral cGVHD that significantly limits oral intake because of pain or dysphagia is appropriately classified as severe, both on an individual and global severity basis as shown in the video and accompanying cGVHD Provider Survey.6 In contrast, the historical classification of isolated oral manifestations as “limited” provides no information on how the cGVHD is affecting the patient. Similarly, many patients with “extensive” cGVHD could have trivial GVHD manifestations in several organs that either singly or together do not significantly impact activities of daily living. Any attempt to prospectively validate this new schema will require diligent assessment of each organ potentially affected by cGVHD.

An added complexity for the patient who is starting a new cGVHD therapy, and who is perhaps enrolled on a cGVHD intervention trial, is how to assess clinical response using measurement tools that were designed and proposed during the Consensus Conference as a first step toward improving objectivity and reliability. The first study of the NIH oral examination scoring showed very good intrarater reliability but only poor to moderate inter-rater reliability.8 More recently, the complete NIH cGVHD assessment was evaluated in 4 consecutive pilot trials, and the results showed that inter-rater reliability estimates were satisfactory for some assessments, including the oral examination, but that very complex measures, such as moveable sclerosis, will probably need further training to achieve improved reliability.9 Although early reports on the use of these instruments have provided mixed results, I see multiple opportunities for improvement. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the oral examination study relied only on the clinical experience of participants and provided no training on how to apply the new scoring system. The study by Mitchell et al provided a single 2.5-hour training session with no opportunity for iterative training and calibration.9 Given that the transplantation community seeks to move the field forward, then more training is needed and some instruments might require modification (or removal) for the comprehensive cGVHD assessment to be accomplished efficiently and reliably.

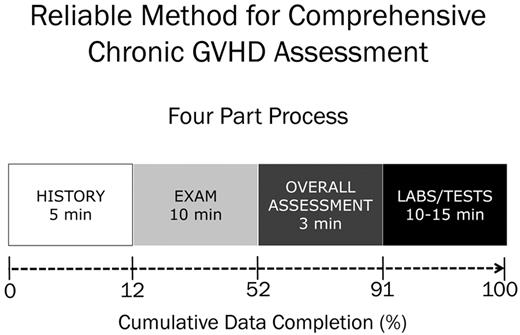

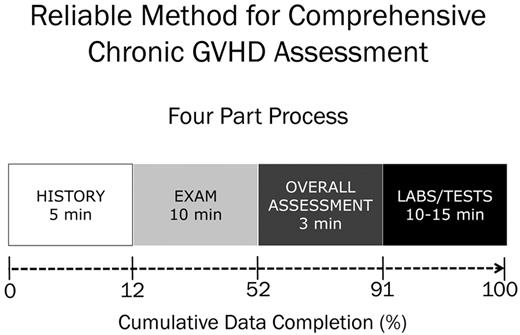

Schema for reliable method

Most processes that are subject to careful scrutiny can be made more efficient and reliable by proceeding in a stepwise manner that has been consciously developed to avoid unnecessary duplication, errors, and back-tracking.10 I think that clinicians ranging from the relatively inexperienced to the very experienced can hone their comprehensive cGVHD assessment to < 17 minutes if they embrace the method, or at least the principles, proposed herein (Figure 1). In this 4-part schema, certain components of the assessment (“Labs/Tests”) may be delegated to a specifically trained nonphysician provider or perhaps to a study coordinator for the patient who is enrolled in a clinical trial. These delegatable items might include the 2-minute walk time, grip strength, Schirmer tear test, pulmonary function testing, and tabulation of laboratory results. It might be possible to save additional time by converting the screening history questions from “Begin with history” into a check box format that a patient completes in the waiting room. One caution here is that face-to-face questioning of patients allows for nuances and clarifications as needed, probably improving data quality and also avoiding the possibility of skipped questions.

Begin with history

As a cGVHD consultant, I often have to ascertain quickly by phone or e-mail from a care provider, or face-to-face with a patient, whether new signs and symptoms might be manifestations of cGVHD, and if so, the severity of the GVHD. Table 1 shows a battery of typical questions that can be given to a patient in the waiting room or given to a provider at a remote site to help screen patients for cGVHD. I find it helpful to take 3-5 minutes myself to run through these 30 or so mostly closed-ended standard questions to glean a more precise assessment of the patient's relevant symptoms and signs. The question of cGVHD severity can be quickly answered because the NIH organ severity scale relies mainly on symptoms to assign the 0- to 3-point score that rates the degree of functional impairment in each organ (Table 1 right column). I always follow up any positive responses with questions aimed at determining the onset of symptoms and their temporal relationship to the tapering of immunosuppressive medications. Familiarity with NIH organ severity definitions, as exampled in the BMT CTN 0801 Provider Survey,6 is advised so that you understand how specific history questions lead to individual organ scoring.

A key point for incorporating history elements into the cGVHD assessment, and especially with regard to form completion, is that symptoms are only scored if you know or suspect that they are related to cGVHD and were present within the last week. The relatedness and duration criteria were arbitrarily defined in an attempt to reduce the cGVHD “signal to noise” ratio. Examples of symptoms that are not scored would include: chemotherapy-associated alopecia, Clostridium difficile toxin-positive enteritis, oral thrush, or confluent acute erythema that was temporally associated with prolonged sun exposure. If I am unsure about causality and the symptoms could be related to GVHD, then I err on the side of scoring them. For example, if the patient has nausea that may or may not be related to a new medication and there has been no time to stop the medication to determine whether the nausea resolves, then I would score this as a GVHD symptom. Another approach would be to assign a proven, probable, or possible GVHD rating and refine the assignment with serial follow-up visits as additional information becomes available.

Physical examination

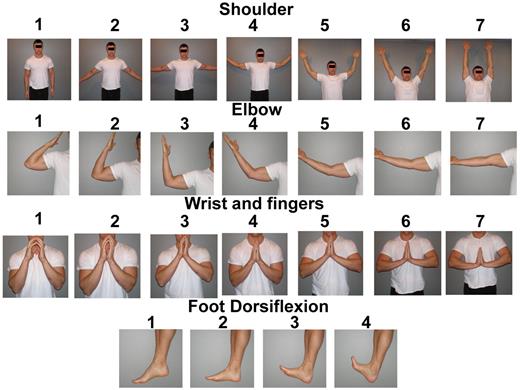

Screening for limited range of motion

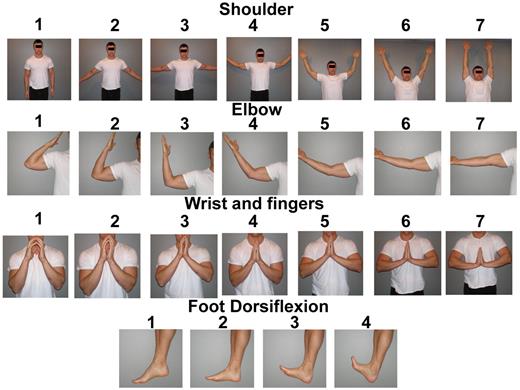

I like to begin the physical examination with 4 maneuvers that quickly screen for sclerosis or fasciitis because either of these manifestations can lead to limited range of joint motion. It is efficient to begin with the gowned patient sitting opposite you on an examination table. In this position within 60 seconds, I can assess flexibility at the small joints of the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, and ankles. Another helpful maneuver in children is to ask them to sit cross-legged as this can bring out limitation of movement at the hips. By sitting directly opposite the patient and demonstrating, I am able to encourage full performance, which is in critical to detect early and often subtle abnormalities of range of motion. For example, when attempting the Buddha Prayer position (Figure 2; see image under score 7 for “Wrist and fingers”) the earliest abnormality may be volar tightening of the forearms if the patient is trying hard to fully extend the wrists. I like to emphasize the forced stretch into full wrist extension with palms held tightly apposed because this will bring out any clawing of the fingers because of fibrosis of the flexor tendon compartment. Eventually, the patient is unable to perfectly appose the palms and fingers during the Prayer position (Figure 2; see images under scores 6-1 for “Wrist and fingers”). If I am unsure whether a patient is simply unable to follow instructions, I take one hand at a time and gently try to force the patient's wrist into extension. I next ask myself whether the patient can fully lock out the elbows to 180 degrees with arms fully stretched out to the sides. Next, can the patient fully raise his or her arms above the head with the upper arms kept close to the ears? If possible but with some difficulty, I ask myself whether this maneuver provokes skin tightening, dimpling, or a grooved appearance to the upper medial arms. Finally, I ask the patient to dorsiflex the feet. Limited dorsiflexion is usually accompanied by Achilles tendon tightening. I then circle the images in Figure 2 that best represent the patient's range of motion and keep this record for future serial comparisons.

Documenting range of motion. Beginning with the full (normal) range of motion on the right, the images indicate progressively more limited range of motion as the numeric scores decrease toward maximally restricted joint motion. By row, from top to bottom, the tasks being attempted are: full shoulder abduction with upper arms brought next to ears, full elbow extension with arms outstretched, “Buddha Prayer” position, and full ankle dorsiflexion.

Documenting range of motion. Beginning with the full (normal) range of motion on the right, the images indicate progressively more limited range of motion as the numeric scores decrease toward maximally restricted joint motion. By row, from top to bottom, the tasks being attempted are: full shoulder abduction with upper arms brought next to ears, full elbow extension with arms outstretched, “Buddha Prayer” position, and full ankle dorsiflexion.

Rapid scoring of oral cavity involvement

I continue my examination with the patient still seated opposite me. With gloved hands and a halogen light source, it usually takes me 60 seconds to score the oral cavity for erythema, lichenoid lesions, ulcers, and mucoceles. It cannot be overemphasized that, without a halogen light source, mucoceles and other subtle lesions will be missed. The light from an examination room otoscope or ophthalmoscope works well. The lesions of interest often appear to overlap, which makes the task often seem daunting. However, using focused “mind's eye” snapshots and an A, B, C approach, it becomes easy to apply the categorical scoring that forms the basis of the NIH oral examination. Other than for mucoceles, total oral surface involvement with the other 3 lesions of interest is used to determine severity. Therefore, a working knowledge of the 5 component parts of the oral surface is essential to accurate scoring. Left and right buccal mucosae together account for 40% of the total scored oral surface, lips, and lower labial mucosa 20%, dorsal tongue 20%, and soft palate and ventrolateral tongue account for the final 20%. For completeness, the gingivae and hard palate are also inspected but do not contribute to scoring.

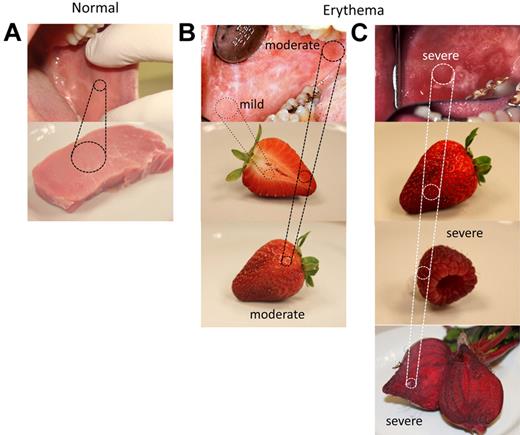

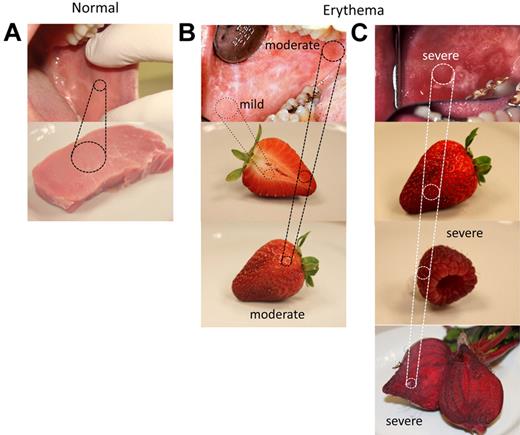

My first snapshot focuses on erythema. Using an A, B, C approach, step A begins by blocking out all other abnormalities besides redness. With step B, I eyeball whether severe erythema covers one-fourth or more of the total oral surface. If yes, then I score 3 and move on to the next snapshot without obsessing on finer detail. If no, step C is to consider whether severe redness is completely absent, and whether any mild redness present. If yes, then provided that moderate redness does not cover one-fourth or more of the total, then I score 1 and move on. Any erythema not satisfying the aforementioned, by default, is given a score of 2 (see video minutes 5:27-6:43).6 I have found that clinicians who are new to scoring tend to overcall severe erythema. To provide a frame of reference for gradations of erythema, the reader might indulge the following analogies. Normal mucosa has the approximate color and erythema intensity of uncooked lean pork (Figure 3A). Mild erythema is like the inner part of an almost ripe strawberry; and moving out toward the skin, the color intensity nicely approximates moderate erythema (Figure 3B). Severe erythema could be the color of the fully ripened strawberry, raspberry, or red beet (Figure 3C). Another area that can be confusing is how to score erythema that might be masked by overlying confluent lichenoid patches. The NIH did not provide guidance on this detail, but my approach has been to try to determine how uniform is the grade of erythema that surrounds the lichenoid patch and also any erythema that is possibly peaking through the patch. If the erythema is fairly consistent, then I will extrapolate that erythema grade to cover the same entire area as the obscuring lichenoid patch.

Frame of reference for grading oral erythema. (A) Normal mucosa has the approximate color of uncooked lean pork. (B) Mild erythema appears similar to the inner part of an almost ripe strawberry; and moving outwards, the more intense color of the skin approximates moderate erythema. (C) Severe erythema is most often the color of a fully ripened strawberry, raspberry, or red beet.

Frame of reference for grading oral erythema. (A) Normal mucosa has the approximate color of uncooked lean pork. (B) Mild erythema appears similar to the inner part of an almost ripe strawberry; and moving outwards, the more intense color of the skin approximates moderate erythema. (C) Severe erythema is most often the color of a fully ripened strawberry, raspberry, or red beet.

My second snapshot focuses on lichenoid lesions. These may range in appearance from lacy white hyperkeratotic striae to confluent white plaques of hyperkeratosis. Again using the A, B, Cs: In step A, I ignore erythema, ulcers, and mucoceles. Then in step B, I ignore lichenoid mimickers, such as the bright white-coated lesions of candidiasis that can usually be scraped off to some degree, or anatomic variants seen in the general population, such as hairy tongue, geographic tongue, and prominent linea alba (see video minutes 6:46-7:24).6 Finally, in step C, I apply 3-point categorical scoring to eyeball whether lichenoid lesions cover less than one-fourth (score 1), more than a half (score 3), or in between (score 2).

My third snapshot focuses on ulcers. Step A begins with blocking out erythema, lichenoid changes, and mucoceles. In step B, I zone in on mucosal sores, often covered in part by whitish-pale yellow pseudomembranes. And in step C, I ask myself whether they cover > 20% (score 3) or < 20% (score 2) of the total oral surface. Not surprisingly, there is no (score 1) mild category of ulcers. In addition, the computer upweights these severe and moderate scores to 6 points and 3 points, respectively, for a total NIH oral score of 15 (see video minutes 7:26-7:55).6

The final snapshot involves directing the halogen light source at the lower inner lip plus the soft palate and eyeballing whether there are > 10, < 5, 5 to 10, or no mucoceles to assign respectively scores of 3, 1, 2, or 0. This completes the oral examination (see video minutes 7:56-9:10).6

Reducing the complexity of the skin examination

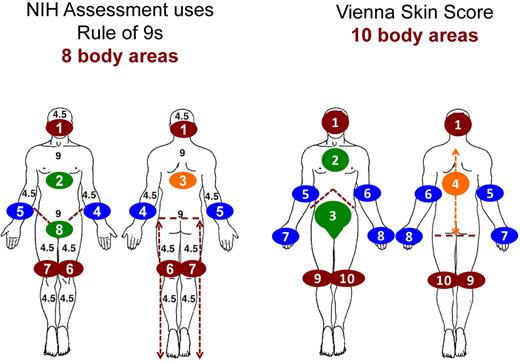

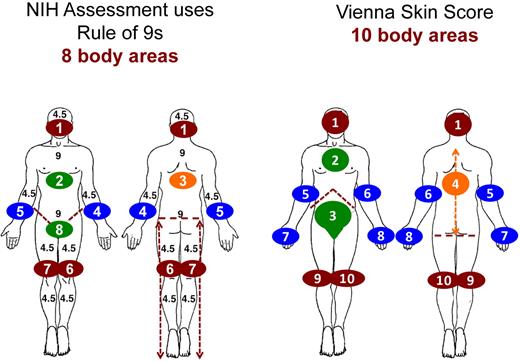

The final component of the physical examination is often the most challenging because the expectation is to score the extent of cGVHD within the entire skin surface. The scoring recognizes that lesions may occupy both superficial and deep layers of the skin, which requires the integration of visual and tactile sensory inputs over a sometimes large and unwieldy body surface. Nonetheless, reductionism allows this task to be accomplished efficiently. I favor a “look, feel, move” approach that is applied iteratively to each of the component skin surfaces. Contemporary trials are comparing the Vienna skin scoring (VSS)11 of 10 skin areas to the NIH skin scoring of 8 skin areas, and both methodologies each have their pros and cons (Table 2; Figure 4). It is efficient to first conduct VSS before NIH because NIH scoring can be extrapolated from VSS for documentation purposes.

Flow of the iterative “look, feel, move” skin examination

The streamlined method has so far maintained the gowned patient sitting toward you, which serves well to initiate the skin examination. I start with the hands by “looking,“ “feeling,” and “moving” the skin to detect cGVHD lesions of interest, noting any textural deviations from normal and defining the extent of any abnormalities relative to the individual Vienna or NIH body area that is being examined. I try always to proceed in an orderly manner to both preserve patient modesty yet examine the entire body surface. With the seated patient, I examine the fingers, hands, and arms and move quickly on to the facial and neck strap muscles that are each palpated for any tightness. I ask the patient to lie prone and I cover the legs while examining the back. It is important to always expose the buttocks because sclerosis may be seen at the base of the spine down to the natal cleft. I then cover the back and buttocks and examine the posterior aspects of the lower legs. After examining the legs in the supine position, I cover the chest and abdomen and expose the anterior legs. If during the look, feel, move iterations, I detect abnormal skin texture, I stop and palpate the contralateral side to better detect textural asymmetries. If I am unsure whether both sides might be affected equally, then textural comparisons with normal can be made with reference to a clearly unaffected body part. On occasion, I resort to referencing the texture of my own skin and tissue if I remain uncertain that a subtle abnormality exists. I am always estimating in my mind what percentage of a designated body area is involved with lesions of interest. Strong familiarity with the body areas used in the VSS and NIH scales maximizes efficiency (Figure 4). Finally, I cover the legs and expose the chest and abdomen to complete the examination, always remembering to examine the genitalia.

Goals of the comprehensive skin examination

Having established the flow for the skin examination, it is important to gather in real time all the relevant information. The first goal is to survey all body areas for diagnostic, distinctive, and any other signs of skin GVHD. The second goal is to quantify the extent of 3 main categories of skin lesion: erythema, dyspigmentation, and sclerosis.

The first is erythema because this is associated with active GVHD. NIH methodology scores erythema separately,1 but VSS has chosen to emphasize the linkage of erythema to areas of moderate and severe sclerosis.11 In VSS, as would be expected, erythema always appears red. However, less intuitively, the NIH approach includes cGVHD rashes that may not always appear red but are scored under the category of erythema because they are considered to be manifestations of active cGVHD rather than postinflammatory lesions such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation.

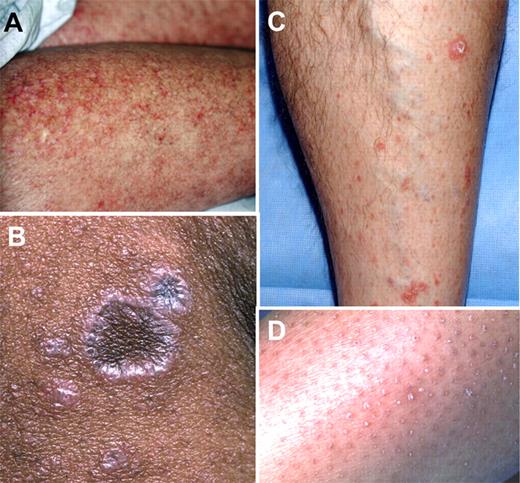

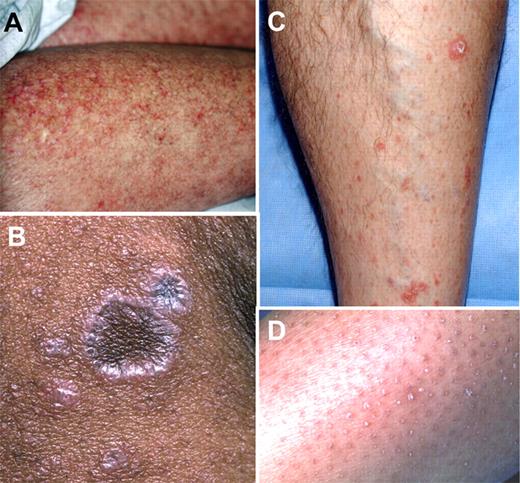

One needs to survey the skin for “classic” and therefore diagnostic lesions of cGVHD.1 These include lichen planus–like lesions or poikiloderma that are quantified under the category of erythema using NIH scoring and under the category of score 1 using the VSS (Figure 5A-B). The other main classic lesions of cGVHD are morphea-like lesions that may preempt their more advanced counterpart, superficial sclerosis. Morphea can be recognized often by its shiny appearance and by textural changes of progressive thickening and reduced pinchability (Figure 6A). Hypopigmentation may also be readily apparent in the adjacent or overlying skin. Severely sclerotic skin often appears shiny and tight, and there may be active inflammation and ulceration (Figure 6B). I pay particular attention to skin dimpling or groove signs that indicate deep sclerosis, even when the superficial skin is not obviously involved (Figure 6C).

Lesions included in the NIH category of erythema. (A) Poikiloderma. (B) Lichen-planus like. (C) Papulosquamous plaques. (D) Keratosis pilaris–like lesions.

Lesions included in the NIH category of erythema. (A) Poikiloderma. (B) Lichen-planus like. (C) Papulosquamous plaques. (D) Keratosis pilaris–like lesions.

Morphea- and sclerodermatous-like cGVHD. (A) Hidebound sclerosis with significant erythema and skin ulcerations. (B) Morphea that is categorized under moveable sclerosis by NIH or VSS 2, and the thickened skin is associated with overlying hypopigmentation and also adjacent hyperpigmentation. (C) Deep sclerosis of the arm showing skin dimpling (thin arrows) and groove sign (thick arrow).

Morphea- and sclerodermatous-like cGVHD. (A) Hidebound sclerosis with significant erythema and skin ulcerations. (B) Morphea that is categorized under moveable sclerosis by NIH or VSS 2, and the thickened skin is associated with overlying hypopigmentation and also adjacent hyperpigmentation. (C) Deep sclerosis of the arm showing skin dimpling (thin arrows) and groove sign (thick arrow).

In contrast to classic lesions that are sufficient to make a cGVHD diagnosis without obtaining biopsy confirmation, I often see “distinctive” lesions that are not unique to cGVHD and therefore, by themselves, are not diagnostic. These include papulosquamous plaques and keratosis pilaris–like lesions that generally appear red but may not be, and once again these are scored under erythema using NIH, or score 1 using VSS (Figure 5C-D). Nail dystrophy occurs commonly and is another distinctive manifestation that is noted but not scored.

The second category of skin lesion is dyspigmentation, which is usually seen after an inflammatory or erythematous phase of GVHD. A key difference between the NIH and VSS scales is that dyspigmentation is ignored by the NIH but given a low score in the VSS.

The third type of lesion is sclerosis, and this is scored dichotomously in the NIH approach as either moveable sclerosis or nonmoveable sclerosis, with the latter category also including deep sclerosis or fasciitis (Figure 6C).

VSS

Rather than the 2-grade NIH approach to sclerosis, the VSS assigns one of 3 possible severity scores. Scores 2 through 4 of the 5-point VSS enable a fairly straightforward approach to categorizing 3 grades of sclerosis.11 Once again, an A, B, C approach to VSS helps me proceed iteratively through all body areas, palpating for early mild sclerotic skin that feels thickened yet moves easily, score 2; upgrading to score 3 for thickened tissue that moves poorly but is still able to be pinched, and upgrading maximally to score 4 if the skin is hidebound and can no longer be pinched. When documenting any of the 10 VSS body parts, step A begins by scoring the most affected areas before least affected areas. This means identifying the percentage of hidebound skin (score 4), then the percentage of poorly moveable but pinchable skin (score 3), then any skin that feels thick but still moves easily (score 2), followed by discolored skin (score 1). It is noteworthy that score 1 is not associated with textural change but rather includes any of the aforementioned types of skin discoloration. Finally, consider the remaining percentage of normal skin (score 0) within the body part. Step B simply notes the fraction of hidebound or poorly moveable sclerosis that also appears red. Therefore, this applies only to the sections of a body part that have been assigned scores of 3 or 4. Step C ensures that the percentages of all scored areas within all 10 body parts total 100%. Preliminary data have shown that intraobserver reliability for the VSS is good to excellent. Interobserver agreement is also moderate to good for scores 0, 3, and 4, but more education and training will be needed to achieve better agreement for scores 1 and 2.11

Particular challenges of skin scoring

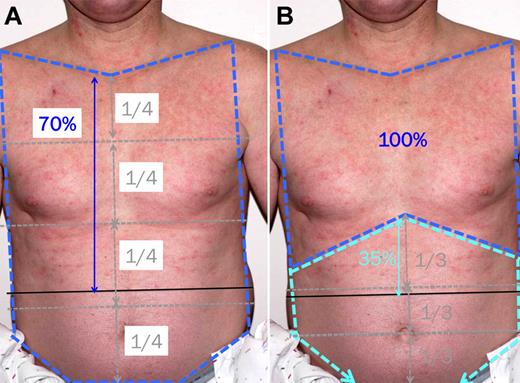

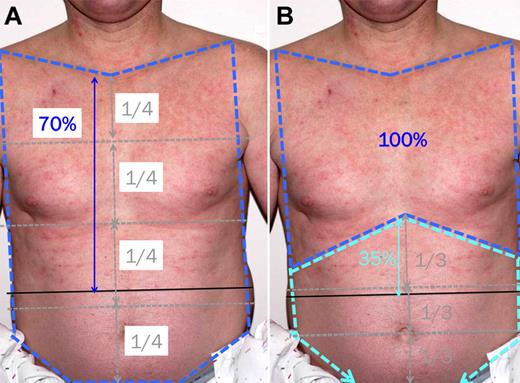

The challenge of skin scoring probably arises from the need to have to simultaneously integrate visuospatial and tactile information to estimate percentages of involvement for each type of lesion of interest within each body part. For details I refer the reader to minutes 14:30 to 19:10 and 24:56 to 27:42 of the video “How to Conduct a Comprehensive Chronic GVHD Assessment” (http://www.fhcrc.org/science/clinical/gvhd/). I find it helpful to visualize each body area fractionated into convenient subdivisions, such as thirds, fourths, or fifths. I then visualize a line of best fit through the periphery of the particular skin abnormality. By then comparing the overall size of this outlined abnormal area with any number of the subdivisions (eg, one-fourth, one-half, three-fourths), I can generally score the abnormal area as a simple fraction from which I can extrapolate the percentage for the entire body area (Figure 7).

Estimating the percentage of skin involvement within a body area. (A) NIH scoring of erythema for the NIH anterior torso body area (dark blue dashed line) involves dividing the area into fourths using your mind's eye, drawing a line of best fit across the lower edge of erythema, to arrive at ∼ 70% involvement. (B) VSS of erythema for the anterior torso involves scoring for 2 body areas. The chest body area (dark blue dashed line) is 100% involved. The abdomen and genitalia body area (light blue dashed line) is divided into thirds using your mind's eye, and a line of best fit across the lower edge of erythema leads to ∼ 35% involvement.

Estimating the percentage of skin involvement within a body area. (A) NIH scoring of erythema for the NIH anterior torso body area (dark blue dashed line) involves dividing the area into fourths using your mind's eye, drawing a line of best fit across the lower edge of erythema, to arrive at ∼ 70% involvement. (B) VSS of erythema for the anterior torso involves scoring for 2 body areas. The chest body area (dark blue dashed line) is 100% involved. The abdomen and genitalia body area (light blue dashed line) is divided into thirds using your mind's eye, and a line of best fit across the lower edge of erythema leads to ∼ 35% involvement.

Early experience with the NIH scale tells us that novice raters tend to overestimate the extent of moveable sclerosis and underestimate the extent of nonmoveable sclerosis. Examples of tricky situations include defining the margins of moveable sclerosis where skin may be thickened and move poorly but is not yet hidebound (equivalent of VSS 3). Another potential problem is when tissue edema during the inflammatory phase of sclerosis, or perhaps as a medication side effect, obscures underlying hidebound sclerosis. Through further use of the NIH and VSS systems and with better understanding of their pitfalls, we might be able to improve inter-rater reliability by providing guidance on how to handle gray areas.

Would a sentinel skin area be helpful?

The third goal of the skin examination in contemporary clinical trials is to prospectively evaluate whether just one sentinel area (typically the worst affected) might serve as a valid baseline for measuring future response to therapy. The analogy would be how sentinel lesions on a chest computed tomography scan might be followed to monitor the response of solid tumor lung metastases to chemotherapy. If this approach could be validated, it would greatly simplify the skin examination.

Use of the mRSS

For patients who are not on current clinical trials, I and several of my experienced colleagues prefer to monitor sclerosis using the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS), which is simpler than the more complex NIH or VSS because it does not require multiple determinations of skin surface areas. The mRSS involves a 0- to 3-point scale to assess skin thickness in 17 body areas, and satisfactory interobserver and good intraobserver reliability has been demonstrated.12,13 The highest score for each area is summed for a total possible mRSS of 51 points, which is sensitive to change with minimally important differences being ∼ 3-5 points.14 Although the mRSS has not been validated in GVHD, we may soon be able to attempt validation in cGVHD by extrapolating mRSS from the VSS by reassigning VSS 0, 2, 3, and 4 with mRSS scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Overall evaluation

The history and physical examination together provide just more than half of the data required to complete the comprehensive cGVHD assessment. For patients enrolled in current clinical trials, such as the 0801 BMT CTN study, it takes just 2 minutes longer to gather another 39% of the remaining data, starting with the assignment of an overall global severity rating using a mild, moderate, and severe scale or a more delineated 0- to 10-point scale. There are also several yes or no checkboxes as to whether therapy was changed (and if yes, why). The clinician is asked to classify whether the patient has no GVHD or whether the patient has late acute, overlap, or classic cGVHD. Another assignment is to check whether a particular organ will guide your treatment decisions; and if there is more than one, rank the order of importance. The overall assessment also captures other indicators or complications of cGVHD that were previously present or currently present and whether they are mild, moderate, or severe. Finally, the assessment captures active infections and severity of peripheral edema, if any (see video minutes 27:56-29:03).6

Labs/Tests

The final 9% of data collection is composed of items that are part of the comprehensive NIH cGVHD assessment and can be obtained by the clinician or, in many instances, by an alternatively trained person. The items include the recording of aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, serum bilirubin, platelet count, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, and corrected diffusing capacity. Three other items are the Schirmer tear test, grip strength for 3 attempts in the dominant hand, and the number of feet walked in 2 minutes using standard protocols that are explained during minutes 29:06 to 32:40 of the video “How to Conduct a Chronic GVHD Assessment” (video details at http://www.fhcrc.org/science/clinical/gvhd/).

How should comprehensive assessments be incorporated in the clinic?

My practice is to run through the 3-5 minutes of screening history at every clinic visit. The comprehensive physical examination takes me < 10 minutes to perform at every visit. However, detailed documentation of the examination findings on the provider survey takes more time and is reserved for more comprehensive visits: every 3 months if the cGVHD disease tempo is aggressive or uncertain and every 6 months if more stable. At my own institution, medical photographs are taken in a standardized manner at initial diagnosis and every 6 months if skin and/or joints are involved until resolution of reversible manifestations or discontinuation of therapy, whichever is longer. The digital images are stored in a separate electronic record and are accessible for serial comparisons from the computer in every examination room. During any clinic visit, the current state of a patient's skin lesions and/or limited joint mobility may be readily compared with archived images taken at prior visits using slide show mode together with zoom-in and zoom-out functions for finer details. Pulmonary function should not be overlooked as part of cGVHD screening. Therefore, formal spirometry with lung volumes and corrected diffusing capacity are done every 3 to 6 months, again based on cGVHD disease tempo. If significant new obstructive changes arise, then spirometry is done monthly 3 times or longer until forced expiratory volume in 1 second stabilizes. Consultation with subspecialists in dental/oral medicine and gynecology might also be indicated at 3- to 6-month intervals or more often as dictated by organ-specific involvement. Annual bone mineral density testing is appropriate for patients receiving glucocorticoids or abnormal prior tests.

In conclusion, my hope is that, through a better understanding of the comprehensive cGVHD assessment, this article and the accompanying video might foster improved efficiency and reliability among the clinicians who typically perform these assessments. Through ongoing prospective validation, it is conceivable that the various approaches might be simplified, modified, or in some cases removed from the overall assessment battery. Whether or not the delegatable items in “Labs/Tests” are performed by the clinician or delegated to another person, the total assessment can be done efficiently in the clinic using the streamlined reliable method as outlined in this video presentation.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Steven Z. Pavletic, Edward W. Cowen, Paul Nghiem, Mark M. Schubert, and Elvira P. Correa for contributing clinical photographs for this article or in the accompanying video produced by Clayton Hilbert and Philip Meadows at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's Collaborative Data Services, and also to Anne Thompson for still life photography in Figure 3.

Authorship

Contribution: P.A.C. wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul A. Carpenter, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Mailstop D5-290, 1100 Fairview Ave N, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: pcarpent@fhcrc.org.