Abstract

Abstract 1658

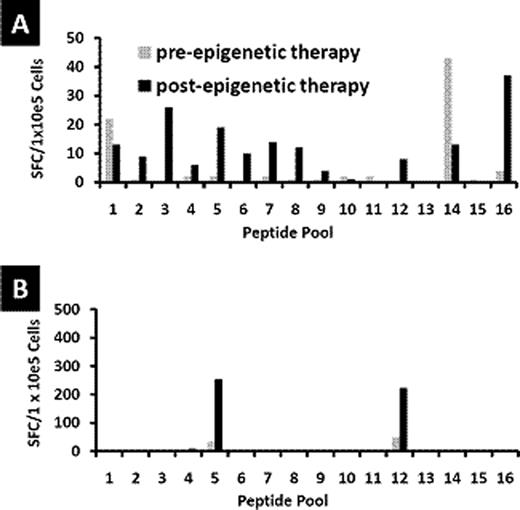

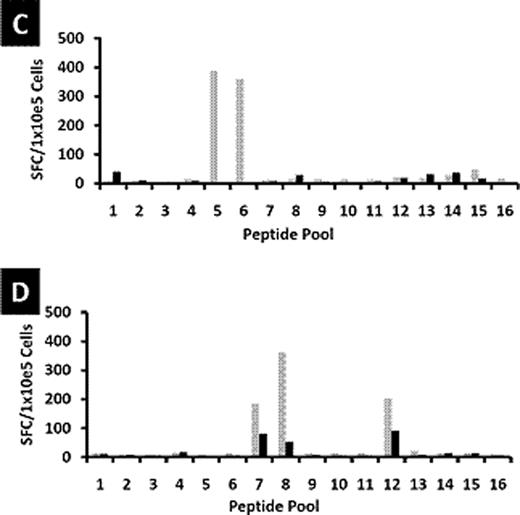

Patients with Hodgkin's Lymphoma (HL) who relapse after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) have limited options for long-term cure. We have shown that infusion of cytotoxic T cells (CTL) targeting Epstein Barr virus (EBV)-derived proteins induced complete remissions in EBV+ HL patients. A limitation of this approach is that up to 70% of relapsed HL tumors are EBV-negative. For these patients, an alternative strategy is to target the cancer/testis antigen MAGE-A4 which is present in EBV antigen-negative Hodgkin's lymphoma tumors. Furthermore, epigenetic modification by clinically available demethylating agents can enhance MAGE-A4 expression in previously MAGE-negative tumors. We explored the feasibility of combining adoptive T-cell therapy with epigenetic modification of tumor antigen expression. We first verified whether MAGE-A4-specific CTL could be expanded from autologous and allogeneic donors. Dendritic cells from healthy donors (n=15) or HL patients (n=9) were pulsed with overlapping peptides spanning the MAGE-A4 protein. Healthy donor T-cell lines expanded to sufficient numbers for clinical use and predominantly comprised CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (mean 60%; range 42–81%) and CD4+ T helper cells (mean 20%; range 8–45%). A mean response of 152 interferon gamma (IFNγ) spot forming cells (SFC)/1 × 105 cells (median 78; range 12–635) was observed against MAGE-A4 peptides compared to a mean of 6 IFNγ SFC/1×105 cells (median 4; range 0–30) to irrelevant peptides. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets contributed to the interferon response. In T cells expanded from the peripheral blood of patients with HL, a mean of 296 SFC/1×105 cells (range 32–1031) responded to MAGE-A4 peptides compared to a mean of 5 SFC/1×105 cells (range 1–11) responding to irrelevant targets. Five of fifteen CTL lines generated from healthy donors showed specificity for a particular peptide (aa266-285, NPARYEFLWGPRALAETSYV). In contrast, T-cell lines derived from HL patients showed a range of MAGE-A4 epitope specificities. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell and dendritic cell numbers were reduced, and T cells from these patients failed to expand after several stimulations consistent with the profound immune deficiency frequently seen in HL patients. We next evaluated the effect of combining MAGE-CTL with the epigenetic-modifying demethylating agent 2'-deoxy-5'azacytidine. To determine if decitabine would negatively affect the function of the TAA-specific T cells, we examined the effects of the drug on the function of MAGEA4-specific T cells in vitro. Our results showed that treatment of T cells with decitabine – in concentrations that exceed expected levels following drug treatment (1 μM) - did not adversely affect the phenotype and function of MAGE-A4 specific T cells in vitro. To evaluate the in vivo effects of decitabine on tumor antigen specific T cells, patient samples were obtained before and after treatment. In patients who received a decitabine containing regimen (75 mg/m2 daily × 5 days) (n=2), one of whom had clinical responses on PET scan, we observed that MAGE-specific T cells were of greater magnitude and recognized a broader number of MAGE-A4 epitopes after decitabine treatment (see Figure below – a and b are patients with a decitabine containing regimen; c and d are patients receiving no decitabine). In patients (n= 2) who did not receive a decitabine containing regimen, the magnitude of MAGE-specific reactivity was reduced, as measured by IFNγ Elispot. These results suggest that although decitabine may modulate immune function, the effect of other chemotherapies may result in the lack of appreciable endogenous T-cell responses to tumor antigens in these patients. Hence, adoptive transfer of MAGE-A4 specific T cells combined with the administration of epigenetic-modifying drugs to increase expression of the target antigens may improve the efficacy of treatment of relapsed Hodgkin's Lymphoma.

Disclosures:

Younes:Celgene: Speakers Bureau; Syndax: Research Funding; SBIO: Research Funding; Genentech: Research Funding; Sanofi-Aventis: Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Novartis: Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Seattle Genetics, Inc.: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau, Travel Expenses; Gilead: Honoraria; Pharmacyclic: Honoraria.

Author notes

*

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

© 2011 by The American Society of Hematology

2011