Abstract

B-cell activating factor (BAFF) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with autoimmune diseases. Because patients with classic and overlap chronic GVHD (cGVHD) have features of autoimmune diseases, we studied the association of recipient and/or donor BAFF SNPs with the phenotype of GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Twenty tagSNPs of the BAFF gene were genotyped in 164 recipient/donor pairs. GVHD after day 100 occurred in 124 (76%) patients: acute GVHD (aGVHD) subtypes (n = 23), overlap GVHD (n = 29), and classic cGVHD (n = 72). In SNP analyses, 9 of the 20 tag SNPs were significant comparing classic/overlap cGVHD versus aGVHD subtypes/no GVHD. In multivariate analyses, 4 recipient BAFF SNPs (rs16972217 [odds ratio = 2.72, P = .004], rs7993590 [odds ratio = 2.35, P = .011], rs12428930 [odds ratio2.53, P = .008], and rs2893321 [odds ratio = 2.48, P = .009]) were independent predictors of GVHD subtypes, adjusted for conventional predictors of cGVHD. This study shows that genetic variation of BAFF modulates GVHD phenotype after allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Introduction

Chronic GVHD (cGVHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT).1,2 The National Institutes of Health consensus criteria for classifying cGVHD have prognostic significance.3-6 Retrospective studies have shown that patients with classic and overlap cGVHD have improved overall survival.4,6 B-cell activating factor (BAFF) is a cytokine of the tumor necrosis factor family that plays an important role in both normal and post-SCT B-cell homeostasis.7-9 Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of BAFF have been associated with the development of autoimmune diseases.10-15 Patients with classic and overlap cGVHD after allo-SCT present with phenotypes that mimic these naturally occurring autoimmune diseases.1 Elevated BAFF to B-cell ratios at 6 months after allo-SCT can predict for the development of cGVHD, thus further linking B-cell homeostasis to GVHD phenotype.16,17 B cells have further been implicated in the pathogenesis of GVHD, as patients who develop antibodies to minor antigens have a higher risk of cGVHD.18 This study hypothesizes that recipient and/or donor BAFF SNPs would be associated with the GVHD phenotype after allo-SCT.

Methods

Adult patients undergoing matched related or unrelated allo-SCT at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from January 1999 to September 2008 with availability of pretransplantation germline recipient and donor DNA samples and surviving until day 120 after allo-SCT (to enrich for patients with cGVHD) were eligible. Mismatched allo-SCT, age < 18 years, and cord blood transplant were excluded. The final cohort consisted of 164 recipient-donor pairs. As previously described, cGVHD classification and severity were determined as per National Institutes of Health criteria, and records were abstracted for transplant characteristics (Table 1).3,5 Seventeen patients experienced either cGVHD or acute GVHD (aGVHD) subtypes between day 100 and day 120. All patients were transplanted on Institutional Review Board-approved or standard of care protocols.

SNP selection and genotyping

A total of 24 tagSNPS were targeted for genotyping, of which 20 passed quality control. TagSNPs were identified using linkage disequilibrium select via the Genome Variation Server (Build 5.09) on the SeattleSNPs Web site (www.gvs.gs.washington.edu/GVS) using a combination of Seattle SNPs and HapMap with the following parameters: (1) minor allele frequency of > 10%, (2) r2 threshold > 0.8, and (3) reference sequence encompassing the 2-kb 5′ and 3′ flanking region. Whole genome amplification was performed using the REPLI-g UltraFast Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Whole genome amplification was verified by RNASE-P analysis on the TaqMan 7200. Genotyping of amplified DNA was performed with a custom GoldenGate (Illumina) combined with VeraCode technology on the BeadXpress reader system according to the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina).

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint for the study was to test for associations between BAFF SNPs and GVHD subtypes (classic/overlap GVHD compared with aGVHD subtypes/no GVHD). Classic and overlap were combined as one category as both of these groups have features of cGVHD. All SNPs analyzed passed quality control (test of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P > .001, minor allele frequency > 0.10, SNP call rate > 0.95, and pair-wise r2 value < 0.8), and linkage disequilibrium was calculated for donors and recipients. All single SNP tests of association were performed using PLINK (www.pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/∼purcell/plink) and included all European-American persons (153 donors and 156 recipients). Univariate logistic regression was performed to test for association between GVHD subtype and each SNP using an unadjusted, additive genetic model. P values were adjusted using false discovery rate,19 and SNPs retaining significance were used in multivariate models. In multivariate analyses, logistic regression was used to test for association of SNPs with GVHD subtypes while adjusting potential confounding variables, such as age at transplantation (continuous variable), donor type (related or unrelated), and source of stem cell (marrow or peripheral blood). As we included patients with a minimum survival of 120 days after allo-SCT, multivariate analyses were done for the entire cohort and also for the subset that experienced GVHD only after day 120 (N = 147). Descriptive statistics, including median and interquartile range for continuous variables as well as percentages and frequencies for categorical variables, were calculated. To test for differences between the 2 groups, χ2 test was used for the categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using PLINK and R 2.10.1 (www.R-project.org).

Results and discussion

Patients

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. GVHD after day 100 occurred in 124 (76%) patients: recurrent/persistent/delayed aGVHD (N = 23), overlap cGVHD (N = 29), and classic cGVHD (N = 72). Among patients with overlap and classic cGVHD (N = 101), mild, moderate, and severe GVHD were seen in 13 (13%), 22 (22%), and 66 (65%) persons, respectively.

Univariate analysis

Because of shared clinical phenotype, overlap and classic cGVHD were combined into a single outcome variable and were compared with patients with aGVHD subtypes and no GVHD after day 100. There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between patients with or without classic plus overlap cGVHD (Table 1). In single SNP analysis, 9 (2 donors, 7 recipients) of the 20 tagSNPs had significant P values of < .05 when comparing classic plus overlap with aGVHD plus no GVHD (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Because the majority of significant SNPs identified were recipient derived, the remainder of the analysis was focused on recipient SNPs. Among patients with classic or overlap cGVHD, there was no significant association between BAFF SNPs with organ involvement or global severity of GVHD (mild/moderate vs severe or mild vs moderate/severe), overall survival, or relapse-free survival (data not shown).

Multivariate analysis

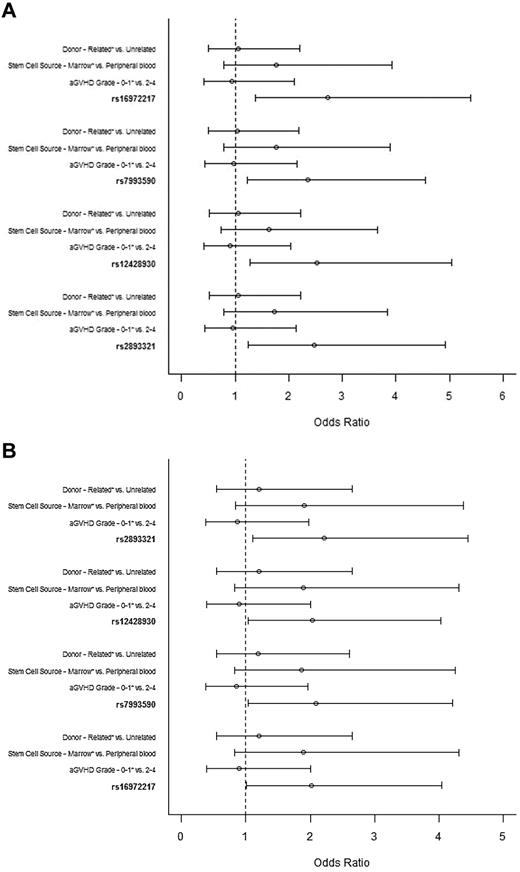

Although no clinical variable was associated with cGVHD (classic plus overlap), multivariate analyses was adjusted for conventional predictors of cGVHD (donor status, stem cell source, aGVHD [before day 100]). After adjusting for false discovery rate, 4 intronic recipient BAFF SNPs remained significant and were used in multivariate analyses. All 4 BAFF SNPs (rs16972217 [odds ratio = 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.38-5.39, P = .004]; rs7993590 [odds ratio = 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22-4.55, P = .011]; rs12428930 [odds ratio = 2.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.27-5.04, P = .008]; and rs2893321 [odds ratio = 2.48; 95% confidence interval, 1.25-4.92, P = .009]) were independent predictors of GVHD phenotype (Figure 1A). The same SNPs retained statistical significance in multivariate analyses done on the subset patients experiencing GVHD after day 120 from allo-SCT (Figure 1B). The other known predictors of cGVHD were not significant.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with GVHD phenotype. (A) Entire cohort. Odds ratio ≥ 1 is associated with increased odds of developing aGVHD subtypes or no GVHD after day 100 from allo-SCT. *Reference group. The tested alleles were as follows: rs16972217, A; rs7993590, T; rs12428930, C; and rs2893321, G. (B) Subset of patients with GVHD after day 120. Odds ratio ≥ 1 is associated with increased odds of developing aGVHD subtypes or no GVHD after day 100 from allo-SCT. *Reference group. The tested alleles were as follows: rs16972217, A; rs7993590, T; rs12428930, C; and rs2893321, G.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with GVHD phenotype. (A) Entire cohort. Odds ratio ≥ 1 is associated with increased odds of developing aGVHD subtypes or no GVHD after day 100 from allo-SCT. *Reference group. The tested alleles were as follows: rs16972217, A; rs7993590, T; rs12428930, C; and rs2893321, G. (B) Subset of patients with GVHD after day 120. Odds ratio ≥ 1 is associated with increased odds of developing aGVHD subtypes or no GVHD after day 100 from allo-SCT. *Reference group. The tested alleles were as follows: rs16972217, A; rs7993590, T; rs12428930, C; and rs2893321, G.

Conclusion

This study shows that recipient BAFF SNPs modulate GVHD phenotype. Multiple observations suggest that B cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of cGVHD.16-18,20-23 The finding of the association of BAFF SNPs with GVHD allows potentially for identification of a subset of patients who may benefit from intervention that modulates the BAFF pathway.

This study is the first to report the association of recipient BAFF SNPs and GVHD phenotype. None of the known clinical predictors of limited/extensive cGVHD was associated with classic or overlap cGVHD. The impact of recipient BAFF SNPs predominated. BAFF production from residual host-derived macrophages,24 dendritic cells, and salivary gland epithelial cells25 possibly explains the association of recipient BAFF SNPs with GVHD subtypes. Of the 3 SNPs previously reported to be associated with increased BAFF levels and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma,26 one SNP (rs12428930) was also an independent predictor of GVHD phenotype.

Our study is limited as we included only patients with a minimum survival of 120 days after allo-SCT. These findings need to be confirmed in a larger cohort along with functional correlation of BAFF SNPs with BAFF levels. Rituximab, starting at 3 months after transplantation, has been used for prophylaxis of cGVHD.27 The association of recipient BAFF SNPs with GVHD phenotype may allow for an individualized approach in the management of GVHD as a predictor of response with rituximab therapy, using rituximab for cGVHD prophylaxis in high-risk patients, and by developing new strategies that target BAFF or alter B-cell homeostasis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Cara Sutcliffe and Dr Holli Dilks, DNA Resource Center, Center for Human Genetics Research; Dr Cindy Vnencak-Jones, Molecular Diagnostics; and Carey Clifton, Catherine Lucid, and Leigh Ann Vaughan, Long Term Transplant Clinic. The Vanderbilt University for Human Genetics Research, Computational Genetics Core provided computational and analytical support for this work.

Authorship

Contribution: W.B.C. and M.H.J. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; W.B.C. and J.S. performed experiments; K.D.B.-G. and D.C.C. advised SNP assay design and analyzed SNP data with PLINK; H.C. and K.-H.F. analyze data and performed statistical analysis; B.G.E. and B.N.S. reviewed and provided critical input in revision of the manuscript; and A.K., J.P.G., and F.G.S. provided critical review for the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Madan H. Jagasia, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2665 Vanderbilt Clinic, Nashville, TN 37232-5505; e-mail: madan.jagasia@vanderbilt.edu.