Abstract

Mutations of the TP53 gene and dysregulation of the TP53 pathway are important in the pathogenesis of many human cancers, including lymphomas. Tumor suppression by p53 occurs via both transcription-dependent activities in the nucleus by which p53 regulates transcription of genes involved in cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis, signaling, transcription, and metabolism; and transcription-independent activities that induces apoptosis and autophagy in the cytoplasm. In lymphoid malignancies, the frequency of TP53 deletions and mutations is lower than in other types of cancer. Nonetheless, the status of TP53 is an independent prognostic factor in most lymphoma types. Dysfunction of TP53 with wild-type coding sequence can result from deregulated gene expression, stability, and activity of p53. To overcome TP53 pathway inactivation, therapeutic delivery of wild-type p53, activation of mutant p53, inhibition of MDM2-mediated degradation of p53, and activation of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways have been explored experimentally and in clinical trials. We review the mechanisms of TP53 dysfunction, recent advances implicated in lymphomagenesis, and therapeutic approaches to overcoming p53 inactivation.

Introduction

The TP53/P53 gene (tumor protein p53), initially identified as an oncogene in 1979, has been recognized as a tumor suppressor gene since 1989.1 Tumor suppressor p53 protein (cellular tumor antigen p53), is “the guardian of the genome,” preserves genome stability under cellular stress, and is involved in various processes of development, differentiation, aging, and disease.2

p53 and tumor suppression

Structure and functions

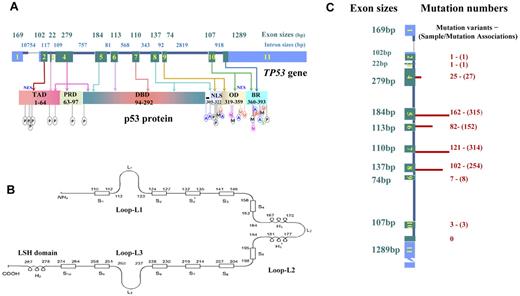

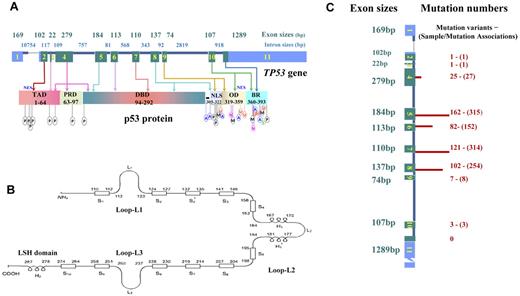

TP53 spans 19 144 bp on chromosome 17p13.1. The dominant TP53 transcript is a 2586-nucleotide (nt) mRNA, including a 5′-untranslated region (UTR) from exons 1 and 2, a 3′-UTR from exon 11, and coding sequence (CDS) from exons 2 to 11, which is translated into the canonical product of p53 consisting of 393 amino acids with several functional domains and motifs (Figure 1).

Schematic structure of TP53 and p53, and numbers of mutations in exons in lymphoid malignancies. (A) TP53 gene structure, p53 functional domains, and posttranslational modifications. Exons are in blue (UTRs) or green (CDS) and are drawn proportionally to their sizes; introns are dark blue and not drawn to scale. Sizes of exons/introns are according to NCBI (reference NC_000017.10 sequence). Domains of p53 include transactivation domain (TAD), proline-rich domain (PRD), DBD, nuclear localization sequence (NLS), oligomerization domain (OD), and basic/repression (BR) of DBD. Both the TAD and OD have a nuclear export signal (NES). Posttranslational modification of p53 can occur by phosphorylation (P), acetylation (A), ubiquitination (U), methylation (M), neddylation (N), or sumoylation (S). (B) Schematic of p53 protein structure. Shown are positions in the p53 primary sequence for 3 loops (L1, L2, L3) involved in DNA binding, 11 β-strands (S1-S10) as components of 2 anti-parallel β-sheets, and 3 α-helices, including 2 in the helix-loop-helix motif. (C) TP53 CDS mutation numbers in lymphoid malignancies. These mutations are not randomly distributed, as indicated by the finding that mutation numbers (shown on right side and illustrated by the length of red bars) in each exon are not proportional to exon sizes (on the left side). Mutation numbers (unique mutation variants and sample/mutation associations) are according to the IARC TP53 database (R15 release, November 2010).

Schematic structure of TP53 and p53, and numbers of mutations in exons in lymphoid malignancies. (A) TP53 gene structure, p53 functional domains, and posttranslational modifications. Exons are in blue (UTRs) or green (CDS) and are drawn proportionally to their sizes; introns are dark blue and not drawn to scale. Sizes of exons/introns are according to NCBI (reference NC_000017.10 sequence). Domains of p53 include transactivation domain (TAD), proline-rich domain (PRD), DBD, nuclear localization sequence (NLS), oligomerization domain (OD), and basic/repression (BR) of DBD. Both the TAD and OD have a nuclear export signal (NES). Posttranslational modification of p53 can occur by phosphorylation (P), acetylation (A), ubiquitination (U), methylation (M), neddylation (N), or sumoylation (S). (B) Schematic of p53 protein structure. Shown are positions in the p53 primary sequence for 3 loops (L1, L2, L3) involved in DNA binding, 11 β-strands (S1-S10) as components of 2 anti-parallel β-sheets, and 3 α-helices, including 2 in the helix-loop-helix motif. (C) TP53 CDS mutation numbers in lymphoid malignancies. These mutations are not randomly distributed, as indicated by the finding that mutation numbers (shown on right side and illustrated by the length of red bars) in each exon are not proportional to exon sizes (on the left side). Mutation numbers (unique mutation variants and sample/mutation associations) are according to the IARC TP53 database (R15 release, November 2010).

p53 is expressed in all tissues with a half-life of approximately 20 minutes under normal conditions because of murine double minute 2 homolog (MDM2)–mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Under stressed conditions, p53 is transcriptionally induced and stabilized/activated by posttranslational modifications (Figure 1).3 It is thought that phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation in stressed cells release p53 from MDM2 inhibition and activate p53, whereas sumoylation and neddylation increase p53 stability by inhibiting ubiquitination and repress p53 function.3,4

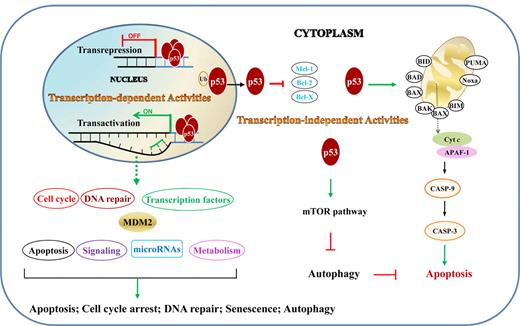

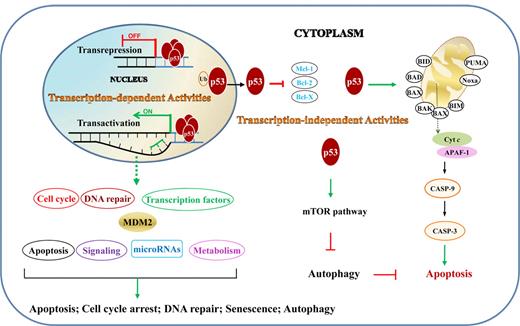

The tumor suppressor function of p53 is reflected in its regulation of cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, and autophagy, through both transcription-dependent and -independent activities (Figure 2).

TAs and TIAs of p53 in lymphocytes. TAs are those that p53 activates or represses in nucleus by binding directly or indirectly to target genes. TIAs include regulation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and autophagy through protein-protein interactions in the cytoplasm. Ub indicates ubiquitination.

TAs and TIAs of p53 in lymphocytes. TAs are those that p53 activates or represses in nucleus by binding directly or indirectly to target genes. TIAs include regulation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and autophagy through protein-protein interactions in the cytoplasm. Ub indicates ubiquitination.

Transcription-dependent activities (TAs) of p53 are required for p53-dependent tumor suppression, as demonstrated in mouse models that succumb to thymic lymphomas because of expression of mutant p53QS (Leu25Trp26 to Gln25Ser26), which abolishes p53 TA but retains its transcription-independent function of apoptosis intact.5 TAs of p53 in lymphocytes (supplemental Table 1; Figure 3)6-11 are distinct from TAs in other cells.11

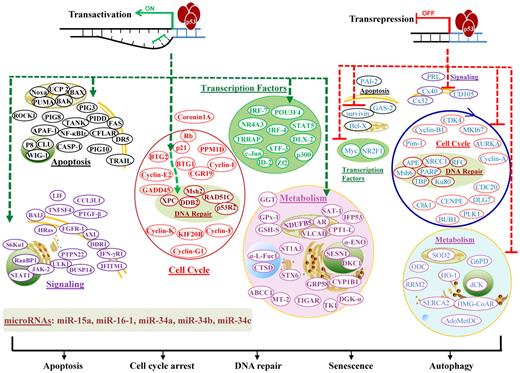

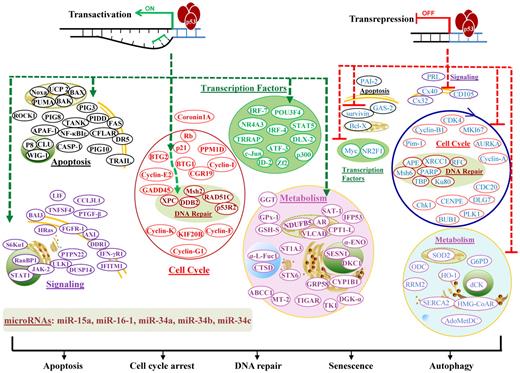

Illustration of p53 TAs in lymphocytes. TAs of p53 transactivate or transrepress hundreds of target genes, whose products are depicted according to their main functions. Downstream events fulfill the tumor suppression function with apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, or autophagy as consequences. In the diagram, green hyphenated lines with arrows indicate up-regulation of gene expression; and red hyphenated lines, down-regulation of gene expression. For the downstream events, proteins/effectors are grouped according to their major functions and subcellular locations. Up-regulated effectors are marked in bold and depicted in colors representing functional groups, whereas down-regulated effectors are not in bold and are all depicted in blue.

Illustration of p53 TAs in lymphocytes. TAs of p53 transactivate or transrepress hundreds of target genes, whose products are depicted according to their main functions. Downstream events fulfill the tumor suppression function with apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, or autophagy as consequences. In the diagram, green hyphenated lines with arrows indicate up-regulation of gene expression; and red hyphenated lines, down-regulation of gene expression. For the downstream events, proteins/effectors are grouped according to their major functions and subcellular locations. Up-regulated effectors are marked in bold and depicted in colors representing functional groups, whereas down-regulated effectors are not in bold and are all depicted in blue.

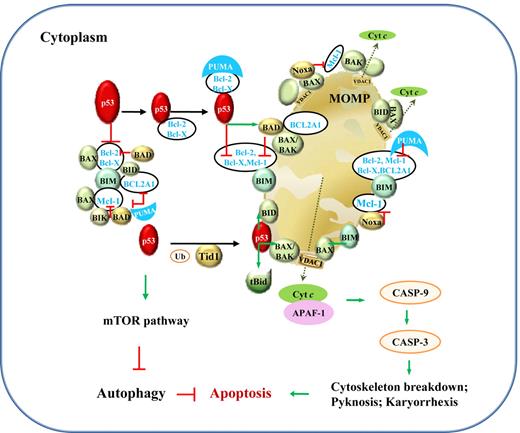

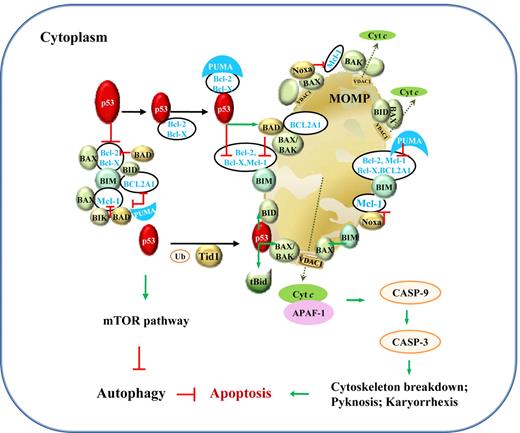

In comparison, transcription-independent activities (TIAs) of p53 are mediated by protein-protein interactions, associated with apoptosis via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway and autophagy (Figure 4). The induction of apoptosis by cytoplasmic p53 has been demonstrated by retrovirus-mediated exclusive delivery of wild-type (WT) p53 with mitochondrial import leader fusions to p53-null or p53-mutant (p53-mut) lymphoma B cells, with low or no infectivity on normal cells.12 This holds hope for the killing of tumor cells without invoking potentially lethal pathology by massive apoptosis. However, the role of p53 is undermined by p53-independent apoptosis pathways. In PW B-cell lymphoma cells, radical oxygen species (ROS) generation, rather than p53, appears to be the key regulator of apoptosis.13

Illustration of p53 TIAs in lymphocytes. TIAs of p53, via protein-protein interactions with Bcl-2 family members and the mTOR pathway, induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and inhibit autophagy. The mechanism for p53-mediated apoptosis is clear, whereas the autophagic role of p53 is not well elucidated. Under stress, PUMA sequestrates Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L), which associate with cytoplasmic p53. Within 30 minutes, cytoplasmic p53 and proapoptotic proteins translocate to mitochondria. In mitochondria, p53 releases BAX, BAK, BIM, and BID from Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), BCL2A1, and Mcl-1; BIK, BAD, and Noxa act in similar ways as p53. Their interactions with antiapoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L) BCL2A1, and Mcl-1 in the cytoplasm are also shown. In addition, transient association of p53 with tBid (BID cleaved by caspase-8 as a result of death-inducing signaling complex activation in extrinsic apoptosis pathway; not shown) or with BAX, BAK, BID, and BAD activates these proapoptotic proteins through structural changes. BAX, BAK, and BID form homo- or hetero-oligomers and trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and consequently cytochrome c (cyt c) release. Cyt c then associates with APAF-1, together activating the downstream caspase cascade leading to apoptosis, preceding a second wave of apoptosis triggered by p53 transcription-dependent activities. The effectors in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis might vary in different cells by different stimuli. Green arrows indicate positive protein-protein interactions, and red lines, negative protein-protein interactions. Ub indicates ubiquitination; and VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1.

Illustration of p53 TIAs in lymphocytes. TIAs of p53, via protein-protein interactions with Bcl-2 family members and the mTOR pathway, induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and inhibit autophagy. The mechanism for p53-mediated apoptosis is clear, whereas the autophagic role of p53 is not well elucidated. Under stress, PUMA sequestrates Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L), which associate with cytoplasmic p53. Within 30 minutes, cytoplasmic p53 and proapoptotic proteins translocate to mitochondria. In mitochondria, p53 releases BAX, BAK, BIM, and BID from Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), BCL2A1, and Mcl-1; BIK, BAD, and Noxa act in similar ways as p53. Their interactions with antiapoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L) BCL2A1, and Mcl-1 in the cytoplasm are also shown. In addition, transient association of p53 with tBid (BID cleaved by caspase-8 as a result of death-inducing signaling complex activation in extrinsic apoptosis pathway; not shown) or with BAX, BAK, BID, and BAD activates these proapoptotic proteins through structural changes. BAX, BAK, and BID form homo- or hetero-oligomers and trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and consequently cytochrome c (cyt c) release. Cyt c then associates with APAF-1, together activating the downstream caspase cascade leading to apoptosis, preceding a second wave of apoptosis triggered by p53 transcription-dependent activities. The effectors in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis might vary in different cells by different stimuli. Green arrows indicate positive protein-protein interactions, and red lines, negative protein-protein interactions. Ub indicates ubiquitination; and VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1.

The role of p53 in autophagy is incompletely elucidated. Cytoplasmic p53 inhibits autophagy by promoting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, whereas nuclear p53 stimulates autophagy by transactivating the mTOR inhibitors, damage-regulated autophagy modulator, and several metabolism genes.3,14 Autophagy is also regulated by PI3K-Akt-mTOR, STK11 (serine/threonine kinase 11)–AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase)–mTOR, Beclin1, Bcl-2, and other molecules.15 Inhibition of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53 has not been investigated in lymphocytes, but induction of autophagy by nuclear p53 has been shown in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) lymphocytes and is associated with drug resistance to dasatinib.16

p53-regulated miRNA genes in lymphocytes

microRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous single-stranded RNAs (∼ 22 nt) that bind to complementary sequences of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or suppression of translation. miRNA genes are transcribed into pri-miRNAs and pre-miRNAs in the nucleus, which are processed into mature miRNAs and anti-sense miRNA* in the cytoplasm. There are 1527 human miRNAs transcribed from approximately 800 published miRNA gene loci in the miRBase 18 database (http://www.mirbase.org, released November 2011).17 Approximately half of mammalian pre-miRNAs are found in non-protein–coding transcripts, and half are located in the introns of protein-coding transcripts from a host gene.

miRNAs transactivated by p53 in lymphocytes include miR-15a, miR-16-1 (targeting oncogene MYB, antiapoptotic BCL2 and MCL1),18 miR-34a (targeting oncogene FOXP1 and BCL2),19 miR-34b, and miR-34c (targeting ZAP70).18 The dysregulation of these miRNAs is associated with poor clinical outcomes.18,19 miR-15a and miR-16-1 are expressed from intron 4 of the LEU2 gene,20 a locus deleted in 55% of CLL cases (del13q14).18 MIR34B and MIR34C loci are deleted in 18% of CLL cases (del11q).18 MIR34A is located at chromosome 1p36.22 and has been suggested to be a p53-induced tumor suppressor in a CLL mouse model.21 The promoter of the MIR15A/MIR16-1 cluster has several p53 responsive-elements, and expression of miR-15a and miR-16-1 correlates with p53 expression.22 p53 induces expression of miR-34a, miRs-34b/34c by directly binding to their promoters.21 miR-34a overexpression can block B-cell development,19 and reduced miR-34a expression has been correlated with inferior overall survival (OS) in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)23 and significantly shorter treatment-free survival in CLL patients.21

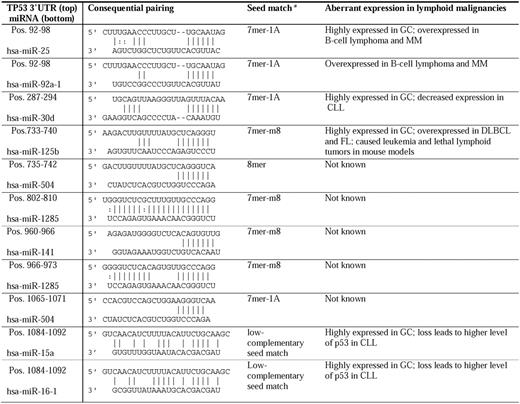

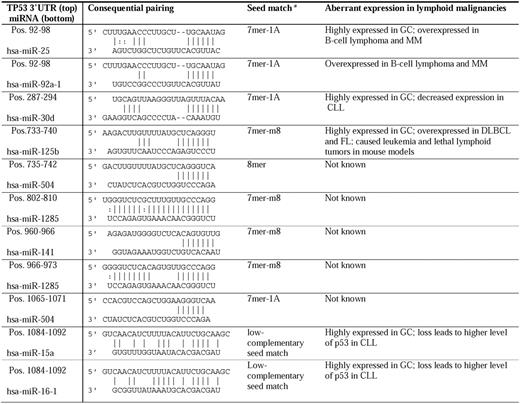

In human lymphoblastoid cell lines,24 p53 induces let-7 miRNA family members, miRNAs (miR-142-3p, miR-142-5p) that are brought close to the 5′ region of MYC because of a translocation,25,26 5 of 7 miRNAs of the miR-17-92 cluster, and other potential oncomirs (miR-155, miR-145, miR-143, and miR-21), although p53 represses the miR-17-92 cluster in colorectal carcinomas.27 In myeloma cells, p53-inducible miRs-192, -194, and -215 target MDM2 and therefore activate p53.28 The aberrant expression and clinical importance of these miRNAs are summarized in Table 1.18,19,21,23,28-35

Effect of p53 activities in lymphocytes

p53 simultaneously promotes cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis, prompting the question as to whether a cell dies or survives after repair. The choice between cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis depends on cell type, cell-cycle stage, extent of DNA damage, p53 level and ratio to p53 isoforms, external survival factors, and internal cellular setting.4,36,37 Lymphocytes are prone to apoptosis under stress compared with other cell types that are prone to permanent cell-cycle arrest, transformation, or mitotic catastrophe leading to p53-independent apoptosis or necrotic death.37 Lethal hematopoietic syndrome resulting from an acute p53 response is characterized by massive apoptosis.37

Drugs can modulate the balance of p53 functions. For example, RO-3306, a CDK1 inhibitor, blocks cell-cycle arrest by inhibiting p53-mediated activation of p21 but enhances apoptosis by reducing levels of antiapoptotic Bcl-2, survivin, and MDM2, and thereby caused enhanced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines with WT-p53.38

On the other hand, when the downstream apoptotic pathway is blocked, or p53 is an apoptosis-deficient mutant, p53 in lymphocytes can enhance cell-cycle arrest and senescence, characterized by irreversible growth arrest, and delay lymphomagenesis, as has been shown in several murine lymphoma models.37,39-41

Apoptosis also appears to be affected by autophagy, although the role of autophagy in cell death or cancer remains debatable. Autophagy correlates with drug resistance and tumor progression in several lymphoid malignancies. In a Myc-induced model of lymphoma, inhibition of autophagy by either chloroquine, an inhibitor of late autophagy, or short hairpin RNA for ATG5, a key autophagy gene, enhanced p53-dependent and -independent apoptosis, suggesting that autophagy is a survival pathway in lymphoma progression.42 Chloroquine also sensitized dasatinib-resistant CLL16 and imatinib-resistant CML cells.43 Oppositely, it has been suggested that cell death induced by bortezomib in multiple myeloma (MM) is via an autophagic pathway.44

Loss of p53 function and lymphomagenesis

In p53-deficient mouse models, either absence45,46 or loss of function,47 malignant lymphoma is the predominant tumor type. Loss of phosphorylation of Ser15 and Ser20 in human p53 was associated with lymphomagenesis of loss of apoptosis in p53-mut mice p5318A, p5323A, and p53S18/23A (Ser18/23 to Ala). In contrast with p53−/− mice, which predominantly develop thymic T-cell lymphomas within 6 months,45,46 most p53S23A mice develop late-onset B-cell lymphomas in lymph node and spleen48 ; some p53S18A mice develop a spectrum of malignancies with late onset, including B-lineage lymphomas and occasionally leukemia.49 Interestingly, no increase in spontaneous tumorigenesis was observed in double-mutant p53S18/23A mice, but accelerated aging did occur.3,49

Disruption of p53-dependent apoptosis is essential for the development and progression of lymphoproliferative diseases.37,50,51 Overexpression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein), and survivin, or deletion/silencing of proapoptotic genes, inactivates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and is implicated in lymphomagenesis. For example, Bcl-2 overexpression resulting from the t(14;18)(q32;q21) in follicular lymphomas (FLs), and deletion, mutation, or silencing of BIM and NOXA in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), and DLBCL,52 appear to be necessary events in lymphoma development.

Mechanisms of TP53 dysfunction in lymphoid malignancies

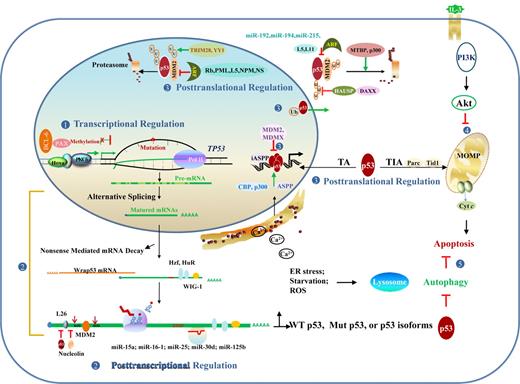

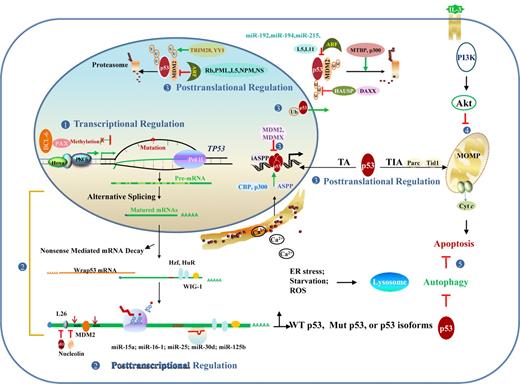

TP53 dysfunction in lymphoid malignancies can arise at the DNA, mRNA, or protein level in cis or in trans, as summarized in Table 2 and Figure 5.

Regulation and dysregulation of TP53 function implicated in lymphomagenesis. (1) At the DNA level, dysregulation of transcription factors and hypermethylation can silence gene expression. (2) At the RNA level, posttranscriptional regulation events include alternative splicing that produces p53 isoforms with altered function, mRNA stability/degradation, and translational regulation. (3) At the protein level, posttranslational modification, redox regulation, and p53 regulators affect p53 stability and function in the nucleus and cytoplasm. (4) p53-independent pathways, including PI3K/Akt affects p53-dependent apoptotic pathway. (5) Autophagy caused by ER stress, starvation, and other forms of stress inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis in most cases. Conversely, cytoplasmic p53 inhibits autophagy by promoting the mTOR pathway, whereas nuclear p53 stimulates autophagy by transactivating genes involved in autophagy. MOMP indicates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; and U or Ub, ubiquitination.

Regulation and dysregulation of TP53 function implicated in lymphomagenesis. (1) At the DNA level, dysregulation of transcription factors and hypermethylation can silence gene expression. (2) At the RNA level, posttranscriptional regulation events include alternative splicing that produces p53 isoforms with altered function, mRNA stability/degradation, and translational regulation. (3) At the protein level, posttranslational modification, redox regulation, and p53 regulators affect p53 stability and function in the nucleus and cytoplasm. (4) p53-independent pathways, including PI3K/Akt affects p53-dependent apoptotic pathway. (5) Autophagy caused by ER stress, starvation, and other forms of stress inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis in most cases. Conversely, cytoplasmic p53 inhibits autophagy by promoting the mTOR pathway, whereas nuclear p53 stimulates autophagy by transactivating genes involved in autophagy. MOMP indicates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; and U or Ub, ubiquitination.

Mutations and polymorphisms of TP53 CDS

p53 mutation patterns.

Mutations in the TP53 CDS have been extensively studied. The curated International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 somatic mutation database (R15 release, November 2010, http://www.iarc.fr) includes 26 608 unique sample/mutation associations, 6.1% of which are from hematologic tumors.53 TP53 CDS mutations occur less often in hematopoietic neoplasms than in many other tumor types: 19.3% in lymphoid malignancies, 11.1% in myeloid malignancies, and 14.9% in lymphoid/plasmacytic malignancies (Table 3).53 Mutations have a lower occurrence (13.6%) in the US population than in developing countries.53

More than 90% of p53 mutations in hematologic malignancies are point mutations, 79.9% of which are missense mutations. Allele deletions have been reported in CLL, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL), FL, and DLBCL. TP53 gene duplication is rare, and translocations involving the TP53 gene have not been reported. A total of 80.7% of p53 mutants have no transactivation function, 10% have partial function, and 9.3% have transactivation function.54 Many p53 mutants act in a dominant-negative manner to inhibit WT-p53 function. Single allele mutations are frequently followed by loss of heterozygosity, which further promotes tumor development.55 The transcription-independent p53 function is also impaired in many mutants. For example, on doxorubicin treatment, p53 mutants in human lymphoma cells can still translocate to mitochondria but cannot induce apoptosis; the latter can be restored by ellipticine.56 On the other hand, some p53 mutants preserve proapoptotic function but lack the ability to translocate to mitochondria, which can be restored by Tid1.57

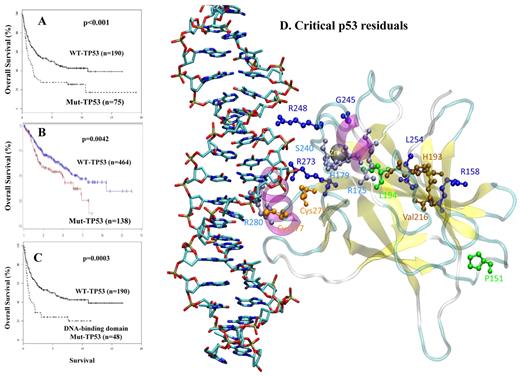

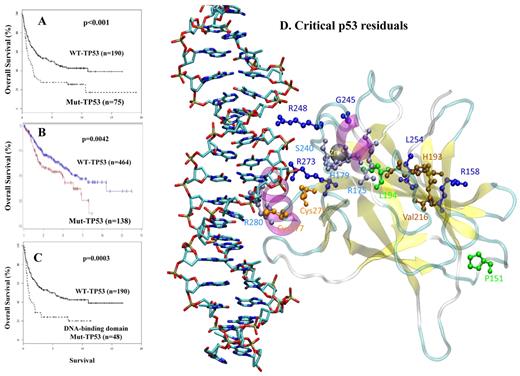

TP53 point mutations in lymphoid malignancies occur most often in the p53 DNA-binding domain (DBD; Figure 1), most frequently at codons 248, 273, and 175, similar to the codon distribution pattern in other types of cancer.55 Four of the 5 mutations at these 3 codons (R175H, R248Q, R273H, and R273C) occur in CpG sites, which have elevated mutability (with the exception of R248W). The high frequency of these mutations is also a reflection of functional selection.58 Codons 248 and 273 bind to minor and major grooves of DNA, and mutations at codon 175 disrupt p53 structure (Figure 6D).59 Indeed, all 5 mutants have lost transactivation function in a p53-functional assay.54 Codons 176, 158, 244, and 245 also have a high frequency of mutation.

The prognostic significance of TP53 mutations in patients with DLCBL. (A) OS (in years) after treatment with the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) regimen among patients with a p53 mutation versus those with WT-p53. (B) OS (in months) after treatment with the rituximab-CHOP regimen among patients with p53 mutations versus those with WT-p53. (C) OS (in years) after CHOP treatment among patients with a TP53 DNA-binding domain mutation versus those with WT-p53. (D) Location of critical p53 residues in the p53 domain model designed from the published crystal structure. The mutations depicted are associated with poor outcome identified from our group study in 1187 DLBCL cases. The residues are color-coded as follows: green represents mutation from or to proline; deep blue, residues close to zinc sites; light blue, residues close to DNA-binding sites; brown, residues far from both zinc and DNA; and orange, cysteine residues implicated in the oxidation-reduction activity of p53.

The prognostic significance of TP53 mutations in patients with DLCBL. (A) OS (in years) after treatment with the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) regimen among patients with a p53 mutation versus those with WT-p53. (B) OS (in months) after treatment with the rituximab-CHOP regimen among patients with p53 mutations versus those with WT-p53. (C) OS (in years) after CHOP treatment among patients with a TP53 DNA-binding domain mutation versus those with WT-p53. (D) Location of critical p53 residues in the p53 domain model designed from the published crystal structure. The mutations depicted are associated with poor outcome identified from our group study in 1187 DLBCL cases. The residues are color-coded as follows: green represents mutation from or to proline; deep blue, residues close to zinc sites; light blue, residues close to DNA-binding sites; brown, residues far from both zinc and DNA; and orange, cysteine residues implicated in the oxidation-reduction activity of p53.

Prognostic significance of p53 mutations in lymphoid malignancies.

Despite the low frequency of p53 mutations in hematologic malignancies, p53 mutations predict an unfavorable prognosis.51,60 The IARC prognosis dataset indicates that p53 mutations correlate with poor survival for patients with DLBCL, AML, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), CLL/SLL, FL, MCL, and MM. Our own studies have shown that TP53 mutations in the DBD significantly correlate with poorer OS in patients with DLBCL (Figure 6). Concurrent p53 mutations and inactivation of other genes with prognostic impact (eg, p21, p27, ATM, p16INK4a, and ARF) have been correlated with a worse prognosis. As overexpression of p53 often correlates with p53 mutations, p53 immunohistochemical staining has been investigated by others, but its prognostic value has been inconsistent, probably because of different antibodies and different cutoffs for positivity. The combined p53+/p21− immunophenotype might be a better surrogate for p53 mutations with prognostic value.

In a 138 B-CLL cohort, p53 mutations correlated with shorter OS and selective resistance to alkylating agents, fludarabine, and γ-irradiation, but not to some other cytotoxic drugs functioning via p53-independent pathways.61 Moreover, prior chemotherapy is strongly associated with the presence of p53 mutations. Exposure to DNA-damaging alkylating agents has been suggested as being responsible for the development of TP53 mutations and resistance to second-line anti-cancer chemotherapy.61 In a more recent study, however, no clonal evolution of new TP53 mutants was identified after chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or bone marrow transplantation in 181 CLL patients.62

In Lane's model of p53 function, tumor cells without functional p53 treated with low-dose DNA-damaging agents survive and continue to replicate resulting in mutations and aneuploidy, whereas in cells treated with high-dose DNA-damaging agents, replication attempts result in mitotic failure and cell death.1 In contrast to the prevailing notion that WT-p53 is associated with better prognosis, it has been suggested that, in the absence of apoptosis, WT-p53 can protect tumor cells treated with ionizing radiation or chemotherapy from mitotic catastrophe or permanent arrest by mediating cell-cycle arrest and DNA repair, and therefore serves as a survival factor.37 WT-p53 also may serve as a survival factor for tumor cells when p53 induces autophagy that inhibits apoptosis. As reported by Amrein et al, autophagy was induced only in primary CLL lymphocytes expressing WT-p53, and contributed to drug resistance.16

Polymorphisms of p53 and association with lymphomagenesis.

TP53 has several polymorphisms, most of which occur in introns or UTRs, whereas 8 synonymous and 11 nonsynonymous polymorphisms occur within the CDS.63 The codon 72 polymorphism has been studied regarding its population prevalence and effects on p53 function. The p53 Pro72 variant has stronger transcriptional activity than Arg72, and is twice as stable as the Arg72 in Daudi (human BL) cells. Arg72 is also more susceptible to degradation induced by the human papillomavirus E6 protein. On the other hand, Arg72 has more capacity to induce apoptosis because of its greater ability to localize to mitochondria and lower affinity to the p53 inhibitor iASPP.63

In one study, 4 of 25 (17.5%) ALL patients carried the R72P (Arg to Pro) polymorphism.64 No association was found between this polymorphism and the risk or prognosis of AML, CLL, FL, DLBCL, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), or non-HL (NHL). Conversely, R72P was associated with increased risk of NHL65 and progression of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL)66 in a Japanese population, and increased risk of NHL in a Korean population.67

Transcriptional dysregulation of TP53 at the DNA level in lymphoid malignancies

Mutations in TP53 promoters.

TP53 has 3 promoters. The canonical p53 transcript is driven by the first promoter, P1, located approximately 300 bp upstream of the first exon. P2 is longer and is located within the first intron, whereas P3, located from exon 2 to intron 4, initiates transcription from intron 4.14,68,69 Differential regulation of P1 and P2 has been observed during differentiation of HL-60 cells to granulocytes or monocytes. Expression from P2 was induced 5- to 10-fold during differentiation, whereas expression from P1 remained constant.70 In 2 of 18 (11%) Li-Fraumeni syndrome or Li-Fraumeni syndrome–like families without TP53 mutations in the CDS and splice junctions, one single nucleotide deletion (A:T) was detected within the C/EBP-like site of the TP53 promoter.71

Transcription factors and methylation.

Numerous transcription factors regulate TP53 transcription by modulating the TP53 promoter, possibly in a tissue-specific manner. Confirmed transcription factors in lymphocytes include the transcriptional repressors PAX-5, BCL-6, oncostatin M, oncoprotein TAX, LANA (latency-associated nuclear antigen), and the activators PKCδ and HOXA5. PAX proteins bind to the TP53 promoter, thereby inhibiting transcription and apoptosis, subsequently important in pro-B-cell differentiation.72 Dysregulation of PAX-5 expression is associated with lymphomagenesis as evidenced by the t(9;14)(p13;q32) in a subset of lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma.73 BCL-6 binds to the TP53 promoter and suppresses TP53 expression, thereby facilitating rapid expansion of the germinal center (GC). Aberrant BCL-6 expression contributes to lymphomagenesis.60,74

Posttranscriptional dysregulation at the mRNA level in lymphoid malignancies

Alternative splicing.

Alternative splicing generates transcript variants that are translated into corresponding isoforms. p53 isoforms expressed in quiescent lymphocytes in a tissue-dependent manner include p53β (p53i9 generated by alternative splicing of intron 9, 341 aa) and p53γ (346 aa) with shorter and different C-terminals compared with p53, Δ40p53s missing 39aa (Δ40p53α, 354 aa; Δ40p53β, 302 aa; and Δ40p53γ, 307 aa) and Δ133p53s missing 132aa (Δ133p53α, 261 aa; Δ133p53β, 209 aa; and Δ133p53γ 214 aa) at the N-terminal regions. Compared with p53 (p53α), these p53 isoforms have different subcellular localization and function, and affect p53 function, but reports have been inconsistent.78-81

Aberrant expression of several novel p53 isoforms has been reported in lymphoid malignancies. A p53 isoform (Δp53) with loss of 66 aa (257-322) produced by alternative splicing was identified in human bone marrow and HSC93 (human B-cell lymphoma) cells.82 Δp53 has a selective transactivation function and acts on a different phase of cell cycle than does full-length p53.82

A TP53 transcript variant, “Delta Ex6,” has been identified in CLL.83 Translation produces a truncated p53 isoform (189 aa) devoid of TA function, based on functional analysis of separated alleles.83 Delta Ex6 and p53β were also found in 1.2% and 2.3% of 1287 CLL cases, respectively.62 Expression of TP53 Delta Ex6 transgene conferred to p53−/− H1299 cells a proliferative phenotype with loss of intercellular contacts and apoptosis defects.

In PW lymphoma cells treated with L-buthionine sulfoximine, the full-length p53 level was unchanged, whereas a truncated isoform of p53 (∼ 50 kDa) was induced, reaching the highest level when apoptosis was induced irreversibly.13 In contrast, the rapid shift from a truncated p53 (Δ, probably p53β) toward the full-length p53 expression was found responsible for the apoptosis and cytopenia as a response to chemotherapy in 5 AML patients.84

Dysregulation of mRNA stability and translation.

Recent investigations have identified novel posttranscriptional mechanisms of TP53 regulation in various cancer cell lines, including regulation of mRNA stability (by Wrap53, HuR, Hzf/hematopoietic zinc finger, WIG-1) and translation (by HuR, Hzf, WIG-1, L26, Nucleolin, p53, MDM2) through the 5′-UTR, 3′-UTR, or CDS.14,85 Isoform Δ40p53 is possibly generated from an alternative internal ribosome entry site because a stem-loop structure formed in the 5′-UTR of p53 mRNA hampers ribosome scanning and translation.80 Interestingly, ARF, which increases p53 protein stability by antagonizing MDM2, was required for the nuclear export of p53 mRNA, with the presence of either Hzf or HuR as a prerequisite.86 These findings suggest that posttranscriptional dysregulation of TP53 may be implicated in lymphomagenesis. A single case of ALL with a one-nucleotide substitution in the 5′-UTR of TP53, which might affect posttranscriptional regulation, has been reported.64

In addition to binding to p53 protein, MDM2 directly binds to the nucleotides of p53 mRNA corresponding to the MDM2-binding domain (MBD) of p53 and enhances TP53 translation. Cancer-derived silent-point-mutations in the MBD weaken MDM2 binding to p53 mRNA, leading to lower levels of p53 protein and apoptosis.87 After p53 is translated, the E3 ligase activity of MDM2 leads to the rapid degradation of p53. Δ40p53 stabilizes p53 in the presence of MDM2.80,81,87

miRNAs targeting the 3′-UTR have emerged as new posttranscriptional regulators. Based on experimental data, 9 miRNAs (miRs-25, -30d, -92a, -125b, 504, -1285, -141, -15, and -16) have been reported to repress the TP53 gene directly (Table 4).18,88-94 miRNAs of interest in lymphocytes include miR-15a and miR-16-1 in CLL,18 miR-25 and miR-30d in MM,88,89 and miR-125b. Interaction of miR-15/16:TP53 is an unconventional low-complementary seed match. The regulation of TP53 by miR-15a/miR-16-1 completes miRNA/TP53 feedback circuitry.18 miRs-15a, -16-1, -25, -30d, and -125b are all highly expressed in GC centroblasts but not in naive (before GC) and memory (after GC) B cells.90 In addition, these p53-regulatory miRNAs have aberrant expression in lymphoid malignancies. The oncogenic clusters miR-17-92 (containing 2 copies of MIR92A) and miR-106b-25 (containing MIR25) are aberrantly overexpressed in B-cell lymphoma95 and MM.91 In contrast, significantly decreased miR-30d expression has been observed in all cases of CLL.29 miR-125b was overexpressed in DLBCL and FL.34 Generally, miR-125b was associated with leukemogenesis in mouse models, but all Eμ/miR-125b transgenic mice developed lethal lymphoid tumors with overexpression of antiapoptotic miR-125b.96

Posttranslational dysregulation of p53 at the protein level in lymphoid malignancies

p53 degradation.

MDM2 mediates polyubiquitination of p53 followed by degradation, both in the cytoplasm and nucleus, and mono-ubiquitination, which enhances nuclear export. Other E3 ligases (Pirh2, COP1, and ARF-BP1) also ubiquitinate p53.14,97 MDMX ubiquitinates but does not degrade p53.4 p53 mutants deficient in MBD can be degraded through oligomerization with WT-p53.98 Oligomerization of p53 with Δ40p53 lacking MBD increases mono-ubiquitination, nuclear export, and stability of p53.81,99

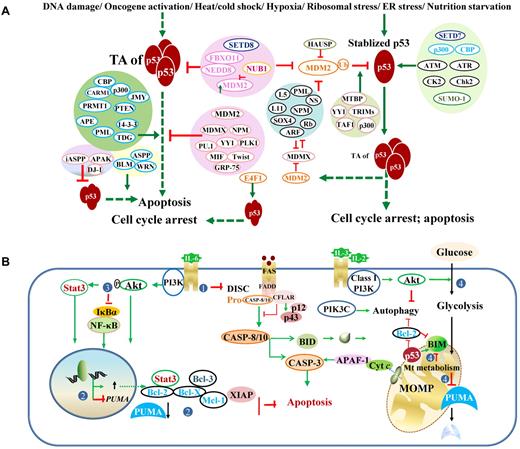

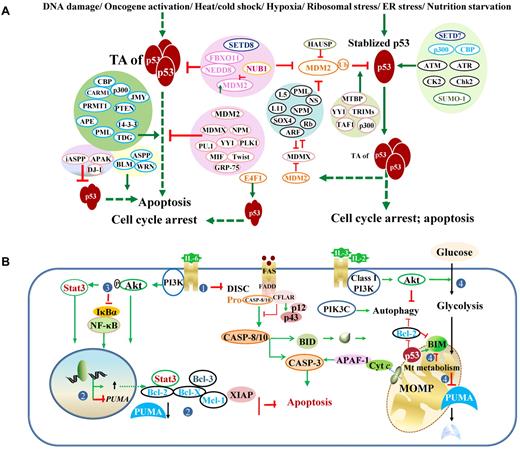

MDM2 overexpression has been associated with tumorigenesis and poorer prognosis in patients with FL, DLBCL, MCL, MZL, BL, ALL, AML, CLL, MM, and plasma cell leukemia. Malignancies also result from dysregulation of MDM2 regulators (illustrated in Figure 7A).4,14,97,100 In BL cells, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of INK4/ARF and epigenetic silencing of the p16INK4a gene were associated with tumor progression.101

Posttranslational regulation of p53 and regulation of p53-effectors. (A) Regulation of p53 transcriptional activities and stability. Under stress conditions, p53 protein is stabilized and activated. Various proteins (mostly shown on the left) and posttranslational modifications (mostly shown on the right) regulate p53 degradation and p53 TAs. Generally, acetylation (eg, by p300, CBP) and phosphorylation (eg, by CK2, Chk2) inhibit ubiquitination, stabilize and enhance p53 activity, whereas neddylation (eg, by FBXO11, NEDD) increases p53 stability but suppresses p53 function. However, association with p300 is required for MDM2-mediated polyubiquitination and degradation of p53. Methylation on different residues has different effects on p53. The methyltransferase SETD7 increases p53 stability; SETD8 inhibits p53 activity. Controversially, Setd7 is dispensable for the p53 function (cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis) in vivo. Effect of sumoylation is also controversial. Acetylation state of SUMO-1 affects its activity toward p53 stability. Ubiquitination decreases p53 stability and activity. MDM2 mediates p53 degradation and inhibits p53 acetylation and activity. NUB1 decreases neddylation by NEDD8 and stimulates p53 ubiquitination, promotes cytoplasmic localization of p53, and inhibits p53 TA. The atypical ubiquitin ligase E4F1 has no effect on p53 degradation or localization but modifies p53 transcriptional program by enhancing cell-cycle arrest and not apoptosis. In the diagram, solid green arrows indicate positive regulation; solid red lines, negative regulation; and hyphenated green arrows, up-regulation of gene expression. (B) Downstream dysregulation of the TP53 pathway by p53-independent pathways, including the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways. The PI3K/Akt pathway counters both the p53-mediated extrinsic (designated as 1: by inhibiting Fas/CD95 death-inducing signaling complex activation without affecting Fas expression) and intrinsic (designated as 2: by increasing antiapoptotic gene expression and decreasing PUMA expression; designated as 4: by suppressing the metabolic up-regulation of PUMA, decreasing PUMA stability, and inhibiting BIM cytotoxicity) apoptotic pathways, and activates the NF-κB pro-survival function (designated as 3: by phosphorylation of NF-κB inhibitor IκBα). DISC indicates death-inducing signaling complex.

Posttranslational regulation of p53 and regulation of p53-effectors. (A) Regulation of p53 transcriptional activities and stability. Under stress conditions, p53 protein is stabilized and activated. Various proteins (mostly shown on the left) and posttranslational modifications (mostly shown on the right) regulate p53 degradation and p53 TAs. Generally, acetylation (eg, by p300, CBP) and phosphorylation (eg, by CK2, Chk2) inhibit ubiquitination, stabilize and enhance p53 activity, whereas neddylation (eg, by FBXO11, NEDD) increases p53 stability but suppresses p53 function. However, association with p300 is required for MDM2-mediated polyubiquitination and degradation of p53. Methylation on different residues has different effects on p53. The methyltransferase SETD7 increases p53 stability; SETD8 inhibits p53 activity. Controversially, Setd7 is dispensable for the p53 function (cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis) in vivo. Effect of sumoylation is also controversial. Acetylation state of SUMO-1 affects its activity toward p53 stability. Ubiquitination decreases p53 stability and activity. MDM2 mediates p53 degradation and inhibits p53 acetylation and activity. NUB1 decreases neddylation by NEDD8 and stimulates p53 ubiquitination, promotes cytoplasmic localization of p53, and inhibits p53 TA. The atypical ubiquitin ligase E4F1 has no effect on p53 degradation or localization but modifies p53 transcriptional program by enhancing cell-cycle arrest and not apoptosis. In the diagram, solid green arrows indicate positive regulation; solid red lines, negative regulation; and hyphenated green arrows, up-regulation of gene expression. (B) Downstream dysregulation of the TP53 pathway by p53-independent pathways, including the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways. The PI3K/Akt pathway counters both the p53-mediated extrinsic (designated as 1: by inhibiting Fas/CD95 death-inducing signaling complex activation without affecting Fas expression) and intrinsic (designated as 2: by increasing antiapoptotic gene expression and decreasing PUMA expression; designated as 4: by suppressing the metabolic up-regulation of PUMA, decreasing PUMA stability, and inhibiting BIM cytotoxicity) apoptotic pathways, and activates the NF-κB pro-survival function (designated as 3: by phosphorylation of NF-κB inhibitor IκBα). DISC indicates death-inducing signaling complex.

Dysfunction of p53 TA.

The activity of p53 is fine-tuned by posttranslational modifications and p53-regulators (Figure 7A),4,14,97,100 adding another mechanism to the ones affecting p53 level. The effects of posttranslational modifications on p53 activity are controversial because of different models and stress conditions used, and interplay between modifications. In addition, p53 has 12 cysteine residues that can be modified by redox, 9 of which are in the DBD. Reduced or oxidized forms of cysteine affect stability, DNA binding, and the transactivation function of p53. Redox modulators influencing p53 include glutathione, REF-1, thioredoxin, metals, and electrophiles.102 Dysregulation of p53 regulators can result in p53 dysfunction without TP53 mutation. Reduced ASPP1 expression resulting from promoter methylation has been found in 25% of ALL cases (n = 180) and correlates with poorer prognosis.103 In CLL, loss of ATM function results in a reduced level of p53 and function.104 MDM2 inhibitors may overcome ATM-mediated resistance to fludarabine in CLL with WT-p53.105

Dysfunction of p53 TIA.

The regulation of TIA of cytoplasmic p53 associated with apoptosis and autophagy is less elucidated than the regulation of TA of nuclear p53.

Tid1 (mtHsp40) and mono-ubiquitination of p53 promote translocation of p53 to mitochondria.57,106 Acetylation of K120 is required for p53 to release BAK from Mcl-1, and for transcription-independent apoptosis.3 Other posttranslational modifications and redox modulation also affect the translocation.3,107

The E3 ubiquitin ligase, CUL-9/Parc, enhances the cytoplasmic function of p53 in vivo. CUL-9/Parc bound to p53 localized in the cytoplasm and activated p53 cytoplasmic function in a mouse model do not support former reports that CUL-9/Parc antagonized p53-mediated apoptosis by sequestering p53 in the cytoplasm. However, the specific biochemical mechanisms that activate p53 cytoplasmic function remain unclear. Deletion of Cul9 accelerated Eμ-Myc–induced lymphomagenesis and attenuated DNA damage-induced apoptosis but had no significant effect on cell-cycle progression.108

Downstream dysregulation of the TP53 pathway.

Lymphomagenesis can result from dysregulation of downstream p53-effectors by p53-independent pathways. In mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, API2/ mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue 1, the result of the t(11;18)(q21;q21), activates NF-κB signaling and inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis, although p53 is induced and subcellular localization is not changed.109

Addition of the cytokine IL-6 or thapsigargin (TG, endoplasmic reticulum [ER] calcium-ATPase inhibitor) inhibits p53-induced apoptosis in mouse myeloid leukemic M1-t-p53 cells.110 Inhibition of apoptosis by IL-6 and TG is partially explained by induction of different p53-independent pathways; p53 transcriptional function was generally not affected. IL-6 did not affect any of the p53-induced proapoptotic genes, whereas TG prevented up-regulation of Gadd45 and Dffb.110

Further investigation showed that IL-6 antagonizes p53 function via the p53-independent PI3K/Akt survival pathway (Figure 7B steps 1-3), which counters both the p53-mediated extrinsic (by inhibiting Fas/CD95 death-inducing signaling complex activation) and intrinsic (by increasing Mcl-1 expression) apoptotic pathways, and activates the NF-κB pro-survival function (by phosphorylation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα).111

In a murine B-ALL cell line dependent on IL-3, after cytokine withdrawal, only cells expressing Bcl-X(L) or active Akt maintain 50% glycolysis and are resistant to apoptosis. Conversely, Akt-mediated cell survival requires glucose metabolism or alternative mitochondrial fuel to prevent apoptosis.112 In contrast, Bcl-X(L) expression strongly protects cells deprived of glucose from apoptosis. Altered metabolism resulting from glucose and/or IL-3 deprivation induces Puma and Bim expression and apoptosis; p53 is required for maximal Puma induction. Activated Akt drives glycolysis to suppress Puma expression via metabolism checkpoints that control p53 activity and to reduce Puma protein stability, as well as inhibit cytotoxicity of Bim protein possibly by phosphorylation (Figure 7B step 4). Similarly, survival of several human T-ALL cell lines, possibly highly glycolytic and with activated Akt, also depends on mitochondrial metabolism.112

Therapeutic approaches to overcome p53 inactivation

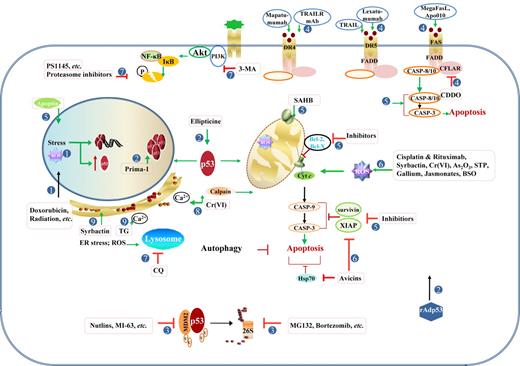

Figure 8 and supplemental Table 2 summarize the drugs and compounds targeting the TP53 pathway reviewed in thisarticle.

Therapeutic modulation of the TP53 pathway. Strategies to activate p53 functions or p53-independent apoptotic pathways have been explored in p53-wt or p53-mut cancer cells. (1) Induction and activation of p53 by stress within the nucleus, including DNA damage caused by alkylating agents, DNA-intercalating agents, base analogs, irradiation, and ROS. Mitotic inhibitors and cell cycle-mediated drugs also effectively activate p53. (2) Therapeutic gene delivery of p53 and pharmacologic activation of p53 mutant. (3) Antagonism of MDM2-mediated degradation by MDM2 inhibitors and proteasome inhibitors. (4) Activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and agonistic anti-TNF antibodies, or CFLAR/c-Flip inhibitors. (5) Enhancement of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis by targeting Bcl-2 and IAP family members, or by directly activating caspases or BAX/BAK. (6) Induction of p53-independent apoptosis by various compounds and agents, mostly via the mitochondrial pathway and ROS generation. (7) Inhibition of survival pathways, including NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, and autophagy. (8) Induction of apoptosis by Cr(VI) through the calcium/Ca2+-calpain pathway and mitochondrial pathway induced by oxidative stress. (9) Increased unfolded/misfolded proteins that can be induced by proteasome inhibitors (Syrbactin, bortezomib), and increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration that can be induced by TG, can induce ER stress and autophagic cell death in several cancer cells.

Therapeutic modulation of the TP53 pathway. Strategies to activate p53 functions or p53-independent apoptotic pathways have been explored in p53-wt or p53-mut cancer cells. (1) Induction and activation of p53 by stress within the nucleus, including DNA damage caused by alkylating agents, DNA-intercalating agents, base analogs, irradiation, and ROS. Mitotic inhibitors and cell cycle-mediated drugs also effectively activate p53. (2) Therapeutic gene delivery of p53 and pharmacologic activation of p53 mutant. (3) Antagonism of MDM2-mediated degradation by MDM2 inhibitors and proteasome inhibitors. (4) Activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and agonistic anti-TNF antibodies, or CFLAR/c-Flip inhibitors. (5) Enhancement of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis by targeting Bcl-2 and IAP family members, or by directly activating caspases or BAX/BAK. (6) Induction of p53-independent apoptosis by various compounds and agents, mostly via the mitochondrial pathway and ROS generation. (7) Inhibition of survival pathways, including NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, and autophagy. (8) Induction of apoptosis by Cr(VI) through the calcium/Ca2+-calpain pathway and mitochondrial pathway induced by oxidative stress. (9) Increased unfolded/misfolded proteins that can be induced by proteasome inhibitors (Syrbactin, bortezomib), and increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration that can be induced by TG, can induce ER stress and autophagic cell death in several cancer cells.

To bypass p53 defects, therapeutic gene delivery of p53 and restoring function of p53 mutants have been explored for chemotherapy-refractory malignancies.56,113,114 However, although activated p53 triggers rapid tumor cell apoptosis in the Eμ-Myc mouse model in vivo, restoration of p53 function potently selects for p53-resistant tumors in which p19ARF or p53 were inactivated.115 Delivery of downstream miRNAs also has been proposed as a potential therapeutic approach, yet many challenges need to be addressed, including nuclease-mediated degradation, adverse off-target effect, toxicity, and unwanted immune response.

Targeting p53 stability, MDM2 inhibitors increase apoptosis and have therapeutic implications in various lymphoma cells. However, early clinical trials with Nutlin-3a have not shown such effects. In an Eμ-Myc mouse model, both Mdm2+/− and Mdm4+/− delayed onset of B-cell lymphoma with increased p53 activity, but hematopoietic failure and cerebellar hypoplasia in double heterozygous Mdm2+/−/Mdm4+/− mice indicate that caution is warranted in the use of the inhibitors of p53 antagonists.116 Similarly, Mdm2−/−p53515C/515C mice (Mdm2- null, and encoding the p53R172P mutant lacking apoptosis ability but maintaining cell-cycle arrest function) died of hematopoietic failure.117 Inhibitors of calpain protease or the proteasome also increased p53 stability and elevated p53 levels and apoptosis.118 However, in MM, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib significantly increased basal autophagy that was thought to protect myeloma cell viability.44 Novel syrbactin analogs exhibiting proteasome inhibitory activity induced proapoptotic ER stress and cell death in MM and B-ALL cells and might substitute for bortezomib.119

Drugs targeting the dysregulated p53-dependent apoptosis pathway include Bcl-2 anti-sense oligonucleotides for CLL, XIAP inhibitor for CLL and ATLL, small-molecule inhibitors of Bcl-2/Bcl-X(L) for CLL, MCL, splenic marginal zone lymphoma, and Bcl-2-dependent lymphomas.120 Stabilization and activation of p53 also can overcome downstream apoptosis pathway defects. MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin-3a increased intrinsic apoptosis in a preclinical model of DLBCL with WT-p53 and Bcl-2 overexpression because of t(14;18)(q32;q21).121 Similarly, Nutlin-3a induced apoptotic death in ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma.122 Interestingly, Nutlin-3a also enhanced doxorubicin cytotoxicity in p53-mut anaplastic large cell lymphoma and DLBCL. This synergistic effect was suggested to be a result of p73 up-regulation.121,122

The potential of anti-cancer drugs that function through p53-independent apoptosis pathways also has been explored. Hexavalent chromium Cr(VI) induced both p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis in U937 lymphoma cells without functional p53.123 The Ca2+-calpain pathway and mitochondrial pathway played significant roles in Cr(VI)–induced G2 block and p53-independent apoptosis. ROS generation was involved in both pathways, whereas c-Jun–N-terminal kinase and FAS activation were not detected.123 The proapoptotic function of the Ca2+-calpain pathway in p53-deficient U937 cells is opposite to the inhibition of apoptosis by calcium mobilizer TG in M1-t-p53 cells,110 and by calpain in LY-ar lymphoma cells with functional p53.118 Indeed, TG induced autophagy when used alone and increased apoptosis when combined with autophagy inhibitors in MM,44 increased ER stress and apoptosis in human MM and B-ALL,119 induced apoptosis in murine lymphoma cells,124 and induced differential apoptosis in human T-cell lymphomas with or without PLCγ1 phospholipase.125 Therefore, both apoptosis and autophagy can be induced by calcium flux, ROS, are affected by the proteasome or protease, and have an effect on mitochondria. It will be interesting to investigate further whether and how apoptosis and autophagy induced by these drugs regulate each other in lymphomas and how their interaction varies according to p53 status.

Similarly, apoptin, DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, gallium maltolate, Avicins, ionizing radiation combined with arsenic trioxide or staurosporine, cisplatin combined with rituximab or fludarabine, can induce p53-independent apoptosis pathways in lymphoma cells regardless of p53 status.123,126-133 Nonapoptotic cell death mechanisms are also implicated in jasmonates (plant stress hormones)-induced cell death of murine B-lymphoma with severe ATP depletion, resulting from compromised oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. The authors suggested that apoptotic death in p53-wt cells is p53-independent, whereas nonapoptotic death, probably necrosis, is responsible for p53-mut cell death.134

Noncanonical autophagy (Beclin1-independent) and apoptosis were simultaneously induced by a novel small-molecule compound C1 via ROS production and subsequent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun-N-terminal kinase in various cell lines.135 More importantly, autophagy triggered by C1 is tumor cell specific, occurring in lymphoma cells but not reactive lymphocytes.135

In conclusion, TP53 pathways through TA and TIA of p53 play important roles in determining cell death or cancer progression. miRNAs, new executors in the TP53 pathway, further add to the complexity of the global regulatory network of p53 functions. Identifying key executors in the TP53 pathway can help stratify patients and develop novel therapeutic strategies. The paradoxical roles of p53 in autophagy by TA and TIA reveal novel p53 functions, but the cytoplasmic autophagic function of p53 in lymphocytes remains unclear. Dysfunction of p53 in lymphoma patients can result from deletion, mutations, and dysregulation of TP53 gene expression and p53 activities. These mechanisms provide lymphoma cells multiple ways to inactivate the functions of the TP53 pathway. Proper function of the TP53 pathway is crucial for tumor suppression and achieving favorable outcome in lymphoma patients. Currently, therapeutic approaches attempt to restore WT-p53 function and maintain p53-dependent and -independent apoptosis yet face problems, such as treatment-induced selection of p53-resistant clones, hematopoietic failure, and inefficient or nonspecific miRNA delivery. Mitochondrially targeted delivery of p53 provides hope for tumor-specific killing without adverse effects. However, TIA of p53 is not sufficient for tumor suppression and TA of p53 is required for tumor suppression in other models. Challenges also come from the fact that these agents could induce autophagy, senescence, or apoptosis in different clinical and biologic contexts. Complicated interactions of autophagy and apoptosis lead to cell death in one scenario but survival of tumor cells in other scenarios. This uncertainty related to drug resistance has been observed with proteasome inhibitors, calcium mobilizers, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, and many other drugs. Inhibition of autophagy has been shown to be a new anti-cancer treatment. On the other hand, autophagy and necrosis may represent alternative approaches to cell death for apoptosis-resistant tumors only if they lead to, but not protect from, cell death. More attractively, some of these drugs specifically target only tumor cells that harbor genetic lesions or defective pathways. Further investigation to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these results will lead to the advent of effective therapeutic intervention.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maitrayee Goswami and Virginia Mohlere from the Department of Scientific Publications for technical and publication editing support. The authors apologize for not including many excellent references because of space limitations.

K.H.Y. was supported by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional R&D Fund, Institutional Research Grant Award, the Myeloma SPORE Development Research Program Award, Gundersen Medical Foundation Award, and Forward Lymphoma Fund. This study is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01CA138688 and 1RC1CA146299, Y.L., K.H.Y.) and the MD Anderson Cancer Center SPORE in Multiple Myeloma (P50CA142509, R.Z.O).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Z.Y.X.-M. and K.H.Y. wrote the paper; and L.J.M., Y.L., R.Z.O., M.A., C.E.B.-R., T.C.G., and T.J.M. provided critical comments and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ken H. Young, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Hematopathology, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77230-1439; e-mail: khyoung@mdanderson.org.