Abstract

We have previously hypothesized that higher systemic exposure to asparaginase may cause increased exposure to dexamethasone, both critical chemotherapeutic agents for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Whether interpatient pharmaco-kinetic differences in dexamethasone contribute to relapse risk has never been studied. The impact of plasma clearance of dexamethasone and anti–asparaginase antibody levels on risk of relapse was assessed in 410 children who were treated on a front-line clinical trial for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and were evaluable for all pharmacologic measures, using multivariate analyses, adjusting for standard clinical and biologic prognostic factors. Dexamethasone clearance (mean ± SD) was higher (P = 3 × 10−8) in patients whose sera was positive (17.7 ± 18.6 L/h per m2) versus nega-tive (10.6 ± 5.99 L/h per m2) for anti–asparaginase antibodies. In multivariate analyses, higher dexamethasone clearance was associated with a higher risk of any relapse (P = .01) and of central nervous system relapse (P = .014). Central nervous system relapse was also more common in patients with anti–asparaginase antibodies (P = .019). In conclusion, systemic clearance of dexamethasone is higher in patients with anti–asparaginase antibodies. Lower exposure to both drugs was associated with an increased risk of relapse.

Introduction

Glucocorticoids and asparaginase are critical chemotherapeutic agents for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Dexamethasone is being used extensively because its use results in lower incidences of bone marrow and central nervous system (CNS) relapse compared with prednisone.1,2 Recently, we observed significant interpatient variability in dexamethasone pharmacokinetics, which could partly be explained by concomitant treatment with asparaginase.3 We found that patients with higher plasma exposure to asparaginase had more profound hypoalbuminemia, lower dexamethasone clearance, and thus increased exposure to dexamethasone, whereas those who received less asparaginase or who developed allergic reactions to asparaginase had lower exposure to dexamethasone.

There are conflicting data as to whether asparaginase allergy or the development of anti–asparaginase antibodies is associated with ALL relapse.4-8 Hitherto, no one has studied the potential impact of dexamethasone pharmacokinetics on the risk of ALL relapse. We hypothesized that lower exposure to both asparaginase and dexamethasone would potentiate the risk of ALL relapse. In this study, we investigated whether the development of anti–asparaginase antibodies is associated with interpatient variability in systemic exposure to dexamethasone and whether these measures are associated with treatment outcome.

Methods

Patients

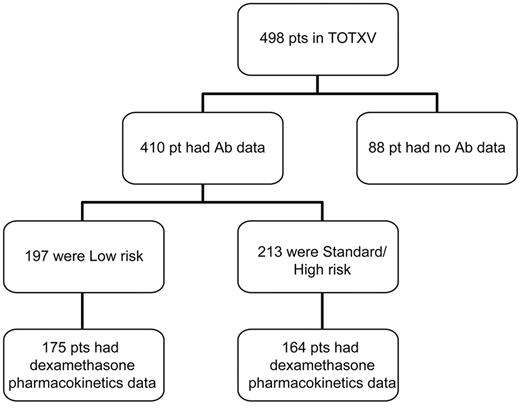

Newly diagnosed children with ALL (N = 498) were enrolled on institutional review board-approved St Jude protocol Total XV, after informed consent was obtained from patients older than 18 years, and from parents or guardians for younger children in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Figure 1).9 Based on presenting clinical and biologic features and on the level of minimal residual disease (MRD) on days 19 and 46, patients were assigned to the low-risk (LR) treatment arm or to the standard- or high-risk (SR/HR) treatment arms.9 Of the 498 patients, 410 patients (197 LR and 213 SR/HR treatment risk arm; Figure 1) had evaluable anti–asparaginase antibody results. Dexamethasone clearance data (at week 8 of continuation phase of therapy) were evaluable in 175 of 197 LR and 164 of 213 SR/HR patients. There were no significant differences in the distribution of clinical features between patients who had evaluable dexamethasone clearance and those who did not (supplemental Table 1), with the exception that the SR/HR risk arm had fewer patients with evaluable dexamethasone clearance compared with the LR group (P = .01). Of the 339 patients with dexamethasone clearance, 214 were included in our prior report.3 Racial ancestry was assigned using germline genetic testing as previously described.10

Consort diagram. A total of 498 children were enrolled on frontline protocol Total XV. Of these, 410 patients (pts) had evaluable anti–asparaginase antibody (Ab), and 339 patients had evaluable dexamethasone apparent oral clearance data, measured at week 8 of continuation phase of therapy. Dexamethasone pharmacokinetics were previously reported for a subset of 214 patients.3

Consort diagram. A total of 498 children were enrolled on frontline protocol Total XV. Of these, 410 patients (pts) had evaluable anti–asparaginase antibody (Ab), and 339 patients had evaluable dexamethasone apparent oral clearance data, measured at week 8 of continuation phase of therapy. Dexamethasone pharmacokinetics were previously reported for a subset of 214 patients.3

Asparaginase and dexamethasone

Treatment regimen and sample collection.

Asparaginase (Elspar) was administered at 10 000 U/m2 per dose intramuscularly thrice weekly for 6 doses (or 9 doses to day 19 MRD+ patients) during remission induction (Figure 2). After a common remission induction and consolidation phase, subsequent doses of dexamethasone and asparaginase therapy differed by treatment arm (Figure 2).9 Patients in the SR/HR arms received 25 000 U/m2 per week of asparaginase from weeks 1 to 19, whereas those in the LR arm received 10 000 U/m2 thrice weekly for 9 doses at weeks 7 to 9 (reinduction I) and weeks 17 to 19 (reinduction II). Dexamethasone at 8 mg/m2 per day (LR arm) and 12 mg/m2 per day (SR/HR arm) was given orally for 5 days on weeks 1, 4, and 14 of continuation therapy. On days 1 to 8 and 15 to 21 of both reinductions I and II, all patients received dexamethasone at 8 mg/m2 per day orally divided into 3 doses.

Overview of asparaginase and glucocorticoid dosing, and sample collection for dexamethasone pharmacokinetics and anti–asparaginase antibody measurement. Patients received prednisone (PRED) at 40 mg/m2 per day during remission induction. Dexamethasone (DEX) was administered at 12 mg/m2 per day (SR/HR arm) and 8 mg/m2 per day (LR arm) in 5-day blocks during continuation weeks 1, 4, and 14; and at 8 mg/m2 on days 1 to 8 and 15 to 21 during reinduction I (weeks 7-9 of continuation) and reinduction II (weeks 17-19 of continuation) for both risk groups. Asparaginase (L-ASP) at 10 000 U/m2 per dose was administered to all patients during remission induction at days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 (and at days 19, 21, and 23 for those with ≥ 1% residual leukemia cells in bone marrow on day 19). During the continuation phase, those in SR/HR arms received 25 000 U/m2 once per week from weeks 1 to 19; those in the LR arm received 10 000 U/m2 thrice weekly at weeks 7 to 9 and 17 to 19. Anti–asparaginase antibodies (ANTI–ASP) were determined on days 5, 19, and 34 of remission induction and day 1 of weeks 7 and 19 of continuation therapy, and dexamethasone pharmacokinetics (PK) were determined on day 1 of week 8 of continuation therapy.

Overview of asparaginase and glucocorticoid dosing, and sample collection for dexamethasone pharmacokinetics and anti–asparaginase antibody measurement. Patients received prednisone (PRED) at 40 mg/m2 per day during remission induction. Dexamethasone (DEX) was administered at 12 mg/m2 per day (SR/HR arm) and 8 mg/m2 per day (LR arm) in 5-day blocks during continuation weeks 1, 4, and 14; and at 8 mg/m2 on days 1 to 8 and 15 to 21 during reinduction I (weeks 7-9 of continuation) and reinduction II (weeks 17-19 of continuation) for both risk groups. Asparaginase (L-ASP) at 10 000 U/m2 per dose was administered to all patients during remission induction at days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 (and at days 19, 21, and 23 for those with ≥ 1% residual leukemia cells in bone marrow on day 19). During the continuation phase, those in SR/HR arms received 25 000 U/m2 once per week from weeks 1 to 19; those in the LR arm received 10 000 U/m2 thrice weekly at weeks 7 to 9 and 17 to 19. Anti–asparaginase antibodies (ANTI–ASP) were determined on days 5, 19, and 34 of remission induction and day 1 of weeks 7 and 19 of continuation therapy, and dexamethasone pharmacokinetics (PK) were determined on day 1 of week 8 of continuation therapy.

We collected blood samples before the morning doses of asparaginase on days 5, 19, and 34 of the induction phase, and on day 1 of reinduction I and reinduction II (corresponding to weeks 7 and 17 of continuation therapy; Figure 2) to measure antibody levels against asparaginase. For dexamethasone pharmacokinetics, blood was drawn before and 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours after the morning dose on day 8 of reinduction I (corresponding to week 8 of continuation therapy; Figure 2). Dexamethasone was measured by HPLC using a 150 × 2.0-mm Phenomenex Luna C182 column (5 μm; Phenomenex), with a limit of detection of 1.36nM, and apparent oral clearance was estimated for 339 patients as previously described.11

Determination of anti–asparaginase antibodies

A total of 2010 blood samples were measured by ELISA for antibodies to 3 forms of asparaginase (Elspar, Erwinase, and Oncaspar), using a modification of our prior methods.12-15 Blood samples were collected on days 5, 19, and 34 during remission induction, and week 7 and week 17 during the continuation phase of therapy (Figure 2). This sampling strategy was designed to have evaluable antibody samples at comparable times relative to asparaginase dosing for all patients. Samples were assessed as positive or negative for antibodies based on optical density readings at a 1:400 dilution, and patients were considered positive for analysis if they had detectable antibody levels for at least one time point. Anti–asparaginase antibody area under the curve (AUC) was calculated separately for Elspar, Erwinase, and Oncaspar. We estimated chronic exposure to asparaginase antibodies based on the anti–Elspar AUC (see supplemental Methods for details, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article); considering the possible cross-reaction between antibodies to Elspar and Oncaspar15 and with uncertain contribution of anti–Erwinase antibodies, we also estimated the sum of the AUCs of antibodies to all 3 forms of asparaginase (see supplemental Methods for details). Asparaginase antibody timing was assessed as the time when the patient first tested positive for anti–Elspar antibody.

Statistics

Relapse definitions were as published.10 The cumulative incidence of any relapse, hematologic relapse, or any CNS relapse (isolated plus combined) was estimated by the method of Kalbfleisch and Prentice16 and compared between groups with the Gray test.17 The Fine and Gray regression model,18 including previously identified prognostic factors (initial leukocyte count, treatment risk arm, age [≥ 10 years or < 10 years], race, ALL lineage, CNS status, MRD status on the date of remission [day 46], and the presence of t(1;19)(TCF3-PBX1) fusion in ALL blasts)9 was applied to investigate any prognostic effect of dexamethasone clearance (continuous variable) and anti–asparaginase antibody status (categorical variable).

Results

Dexamethasone clearance differed by patient age and treatment arm

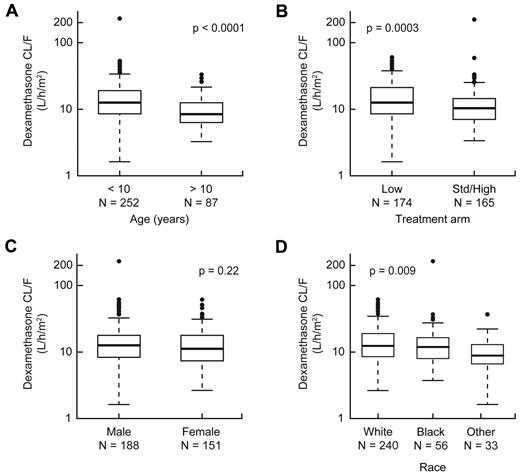

We investigated how clinical features might confound any associations between dexamethasone pharmacokinetics and therapeutic outcomes. In univariate analyses, lower clearance (hence higher exposure) to dexamethasone was associated with older age group (P < .0001) or SR/HR treatment arm (P = .0003; Figure 3A-B). Patients with white or black genetic ancestry had higher dexamethasone clearance than those with other genetic ancestries (Figure 3D). Dexamethasone clearance was not associated with sex (Figure 3C), MRD status, ALL lineage, or most other presenting features (supplemental Table 2).

Dexamethasone clearance was affected by age and treatment risk group. Association of dexamethasone apparent oral clearance with age (A), treatment arm (B), sex (C), and race (D).

Dexamethasone clearance was affected by age and treatment risk group. Association of dexamethasone apparent oral clearance with age (A), treatment arm (B), sex (C), and race (D).

Anti–asparaginase antibody status differed by race, treatment arm, and immunophenotype

Consistent with our prior report on asparaginase allergy,19 the proportion of patients positive for anti–asparaginase antibodies to Elspar was higher among those treated on the LR arm than among those on the SR/HR arm (69% vs 47%, P < .00001, supplemental Table 3). Clinical allergy to asparaginase was also more common among patients on the LR than those on the SR/HR treatment arms (51% vs 32%, C.L., J.D.K., C.C., D.P., C.A.F., X. Cai, K. Crews, S. Kaste, J.C.P., W.P.B., S. Jeha, J. Sandlund, W.E.E., C.-H.P., M.V.R., unpublished data, December 2011) and was also associated with higher dexamethasone clearance (supplemental Figure 1). We also investigated whether other clinical features were associated with the presence of anti–asparaginase antibodies. Age, sex, and MRD were not associated with antibody status (supplemental Table 3), but the frequencies of positive antibodies at any time of therapy were 62% in white, 56% in black, and 39% in patients of other ancestries (P = .006, supplemental Table 3). Anti–asparaginase antibodies were detected more frequently in patients with B-lineage ALL than in those with T-cell ALL (62% vs 35%, P = .0001, supplemental Table 3).

Effect of anti–asparaginase antibody on dexamethasone pharmacokinetics

Patients who tested positive for anti–Elspar antibodies at any time during therapy had higher apparent oral clearance (average ± SD) of dexamethasone (17.7 ± 18.6 L/h per m2 vs 10.6 ± 5.99 L/h per m2; P = 3 × 10−8, Figure 4A) and correspondingly lower plasma dexamethasone AUC (527.7 ± 308.5nM*h vs 756.9 ± 398.4nM*h; P = 5 × 10−9, Figure 4B). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the level of anti–Elspar antibody and dexamethasone clearance (Figure 4C) and a corresponding inverse correlation with dexamethasone AUC (Figure 4D). When the sum of antibody AUCs to all 3 forms of asparaginase was analyzed, correlations with dexamethasone pharmacokinetics were essentially identical (data not shown). In addition, consistent with the preliminary observation by Yang et al3 in a smaller subset of patients, higher serum albumin was associated with higher dexamethasone clearance (P = 3 × 10−4) and correspondingly lower dexamethasone AUC (P = 1 × 10−6, supplemental Figure 2).

Patients with anti–asparaginase antibodies had higher dexamethasone clearance. Patients who tested positive for anti–asparaginase antibodies had (A) higher dexamethasone clearance and (B) lower dexamethasone exposure (AUC). The level of anti–asparaginase antibodies over time (AUC) was correlated directly with dexamethasone clearance (C) and inversely with dexamethasone plasma exposure (D).

Patients with anti–asparaginase antibodies had higher dexamethasone clearance. Patients who tested positive for anti–asparaginase antibodies had (A) higher dexamethasone clearance and (B) lower dexamethasone exposure (AUC). The level of anti–asparaginase antibodies over time (AUC) was correlated directly with dexamethasone clearance (C) and inversely with dexamethasone plasma exposure (D).

Pharmacologic measures and relapse

In univariate analyses, dexamethasone clearance was associated with the cumulative incidence of any relapse (hematologic, CNS, combined, and other, P = .003) and of any CNS relapse (CNS and CNS + hematologic, P = .001) but not with hematologic relapse (isolated or combined with CNS, P = .24). In multivariate analyses, including covariates that are known prognostic risk factors and those significantly associated with treatment outcome in the primary protocol analysis,9 higher dexamethasone clearance remained significantly associated with any relapse (P = .0104, Table 1) along with SR/HR treatment arm (P = .0035) and African ancestry (P = .0261). Furthermore, higher dexamethasone clearance was associated with any relapse (P = .008) when the analysis was restricted to the SR/HR treatment group.

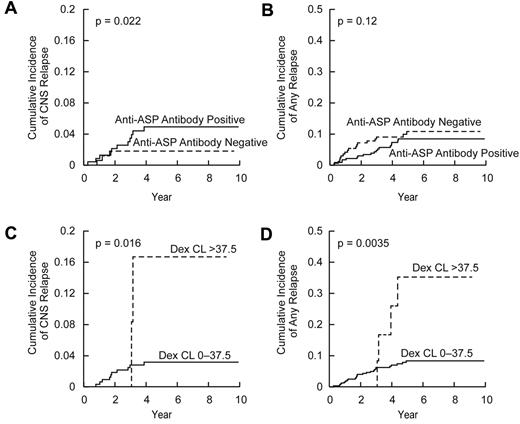

In multivariate analysis, CNS status at diagnosis (P = .006), dexamethasone clearance (P = .014), and positive anti–Elspar antibody status (P = .019) were independently associated with the cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (Table 2; Figure 5A,C). Moreover, CNS status at diagnosis (P = .008) and positive anti–Elspar antibody status (P = .02) were associated with CNS relapse when the analysis was restricted to the SR/HR patient subset.

Cumulative incidence of relapse based on dexamethasone clearance and anti–asparaginase antibody status. Cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (A) and any (hematologic, CNS, combined, and other) relapse (B) in patients who became positive (N = 207) versus those who remained negative (N = 132) for anti–asparaginase (ASP) antibodies with P values based on multivariate analysis (Table 1). Cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (C) and any relapse (D) in patients with dexamethasone (Dex) clearance (CL) greater than (N = 12) versus lower (N = 327) than 37.5 L/h per m2 with P values based on log-rank test.

Cumulative incidence of relapse based on dexamethasone clearance and anti–asparaginase antibody status. Cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (A) and any (hematologic, CNS, combined, and other) relapse (B) in patients who became positive (N = 207) versus those who remained negative (N = 132) for anti–asparaginase (ASP) antibodies with P values based on multivariate analysis (Table 1). Cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (C) and any relapse (D) in patients with dexamethasone (Dex) clearance (CL) greater than (N = 12) versus lower (N = 327) than 37.5 L/h per m2 with P values based on log-rank test.

CART analysis

To identify threshold values for dexamethasone clearance that might be important for evaluating risk factors for relapse, we performed classification and regression tree (CART) analysis, which allows sequential division of the cohort based on dichotomization of prognostic features, in their order of prognostic importance. CART analysis included all covariates used in the multivariate analysis (Table 1), with cumulative incidence of any relapse as a dependent variable. The 339 patients were first dichotomized based on treatment arm (supplemental Figure 3), with those in the LR arm having fewer relapses than those in SR/HR arm. In the LR arm, patients with dexamethasone clearance greater than 37.5 L/h per m2 were at higher risk of relapse than those with lower dexamethasone clearance. Interestingly, when all patients (LR and SR/HR) were analyzed, patients with dexamethasone clearance greater than 37.5 L/h per m2 had a significantly higher cumulative incidence of CNS relapse (16.7% ± 11.3%, P = .016, Figure 5C) and any relapse (35.2% ± 15.1%, P = .0035, Figure 5D) than those with lower clearance (3.2% ± 1.0% for CNS relapse and 8.3% ± 1.6% for any relapse). In the SR/HR treatment arms, patients with African genetic ancestry had a higher risk of relapse (supplemental Figure 3).

Discussion

The inclusion of dexamethasone20-22 and increased dose intensity of asparaginase has significantly improved event-free survival and decreased the risk of hematologic and CNS relapses in pediatric ALL.23-27 In randomized trials, dexamethasone yielded better event-free survival and fewer CNS and hematologic relapses compared with prednisolone or prednisone.1,2 Herein, we confirmed our preliminary observations that there is an interaction between asparaginase treatment and dexamethasone systemic exposure3 ; and for the first time, we have shown that interpatient variability in exposure to dexamethasone affects the risk of both hematologic and CNS relapse.

Patients who had higher asparaginase exposure, by virtue of being on the SR/HR treatment arm or because they lacked anti–asparaginase antibodies, had lower dexamethasone clearance and consequently higher dexamethasone exposure, whereas those who received less asparaginase had lower exposure to plasma dexamethasone. Consistent with our prior report on asparaginase allergy,19 the proportion of patients positive for anti–asparaginase antibodies to Elspar was higher among those treated on the LR arm than among those on the SR/HR arm (69% vs 47%, P < .00001, supplemental Table 3). The higher the antibody level, the higher the dexamethasone clearance (Figure 4C) and the lower the dexamethasone AUC (Figure 4D). Thus, patients who develop asparaginase allergy may be doubly disadvantaged, as they have less exposure to 2 of the major antileukemic agents used in ALL. We hypothesize that asparaginase may decrease dexamethasone clearance because of its hypoproteinemic effects, particularly on hepatic protein synthesis.28,29 It should be noted that, although dexamethasone is moderately bound (∼ 80%) to plasma proteins, including albumin, hypoalbuminemia caused by asparaginase is probably not the mechanism by which clearance of dexamethasone is increased; because dexamethasone is a low-intrinsic-clearance drug, only unbound drug is cleared, and any free drug displaced from plasma proteins is available for clearance. Dexamethasone is metabolized by CYP3A cytochromes P450. Decreased synthesis of hepatic P450s and transporters, for example, could result in decreased clearance of dexamethasone by decreasing its hepatic metabolism or decreasing its excretion.3 Other concurrent supportive care therapies, such as azole antifungals, may also affect dexamethasone clearance.

Regardless of the mechanism, variation in asparaginase exposure among patients results in variation in dexamethasone exposure. Pharmacokinetic variability for other antileukemic agents (methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine30,31 ) has been associated with variation in treatment outcome; on St Jude Total XV, we adjusted doses of methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine based on pharmacokinetic parameters to avoid suboptimal exposure to these agents9 ; however, variability in disposition of dexamethasone and asparaginase persisted, as these agents were not adjusted based on pharmacokinetics. We therefore reasoned that patients who had lower exposure of dexamethasone and asparaginase might have a higher risk of relapse. The close interaction between the 2 drugs supports our approach of considering how the combination of both anti–asparaginase antibodies and dexamethasone clearance is associated with treatment outcome.

In multivariate analysis, including dexamethasone clearance, anti–asparaginase antibody status, treatment arm, age, race, and other prognostic covariates,9 higher dexamethasone clearance was associated with a higher risk of any type of relapse (hematologic, CNS, combined, and other; Table 1; Figure 5) in all patients and when the analysis was restricted to SR/HR patients. The CART analysis (supplemental Figure 3) revealed that dexamethasone clearance was prognostic in patients on the LR arm as well. Moreover, the cumulative incidences of any relapse and of CNS relapse (Figure 5C-D) in all patients were higher in patients with clearance greater than 37.5 L/h per m2 compared with patients with lower dexamethasone clearance. Patients whose clearance was greater than 37.5 L/h per m2 had much lower dexamethasone systemic exposure, with average trough (3.1 ± 2.8 vs 40.8 ± 35.8nM) and average Cmax (50.7 ± 34.0 vs 141.3 ± 68.7nM) plasma concentrations substantially lower compared with patients with lower dexamethasone clearance. Interestingly, trough plasma dexamethasone concentrations of approximately 3nM are slightly lower than the median dexamethasone IC50 of 7.5nM observed in B-lineage ALL32 and in other dexamethasone-sensitive leukemia cell lines,33 consistent with the notion that, for high-clearance patients, exposure to dexamethasone was subtherapeutic, thereby increasing their risk for relapse. Surprisingly, MRD at day 46, which was prognostic in a univariate analysis,9 trended in the right direction but was not significant in this multivariate analysis that include multiple additional covariates.

Multivariate analyses revealed that both higher dexamethasone clearance and positive anti–asparaginase antibody status were independent risk factors for CNS relapse (Table 2). These findings suggest that anti–asparaginase antibodies may have a direct impact on CNS relapse, not just via an indirect effect of its influence on dexamethasone clearance. Although asparaginase does not cross the blood-brain barrier, it depletes asparagine in the cerebrospinal fluid, which is in equilibrium with asparagine levels in the plasma.34,35 The importance of asparaginase in preventing CNS relapse is supported by randomized studies of Erwinia versus Escherichia coli asparaginase,26,27 with the somewhat more favorable pharmacokinetic profile of Escherichia coli yielding better event-free survival and fewer CNS relapses compared with Erwinia asparaginase.

In conclusion, our data support the importance of adequately dosing dexamethasone and asparaginase in ALL. We have shown that interindividual variability in dexamethasone pharmacokinetics was influenced by anti–asparaginase antibodies and that both of these variables affected the efficacy of ALL treatment. Anti–asparaginase antibodies were particularly important in affecting CNS relapse, a finding consistent with the idea that asparaginase is one of the agents making an important contribution to the treatment of CNS disease despite its lack of penetration into the CNS. Possible strategies to minimize allergic reactions include avoiding no-asparaginase “holidays” and perhaps pretreatment with antihistamines or glucocorticoids, but such strategies remain to be tested. Optimizing therapy to minimize allergic reactions is predicted to not only improve asparaginase effects but also to improve exposure to dexamethasone, and perhaps to other ALL medications.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research nurses, clinical staff, and patients and their parents for their participation; May Chung, Natalya Lenchik, and Drs Wenjian Yang, Xiangjun Cai, and Kristine Crews at St Jude; and Dr Lawrence Hak and his research group at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grants CA 142665, CA 36401, and CA 21765), the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Pharmacogenomics Research Network (U01 GM92666), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.V.R. and J.D.K. conceived and designed the project, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; C.L. analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; C.A.F. assisted in developing the anti–asparaginase antibody assay; J.C.P. determined dexamethasone pharmacokinetics; D.P. and C.C. performed the statistical analyses; W.E.E., S.C.H., D.C., W.P.B., and C.-H.P. were investigators for the clinical protocols; and all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.V.R. receives a portion of the income St Jude receives from licensing patent rights related to TPMT and GGH polymorphisms, and funding for investigator-initiated research on the pharmacology of asparaginase from Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals. W.E.E. receives a portion of the income St Jude receives from licensing patent rights related to TPMT and GGH polymorphisms. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary V. Relling, St Jude Children's Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Place, Memphis, TN 38105-2794; e-mail: mary.relling@stjude.org.