Abstract

CTLA-4 inhibits T-cell activation and protects against the development of autoimmunity. We and others previously showed that the coreceptor can induce T-cell motility and shorten dwell times with dendritic cells (DCs). However, it has been unclear whether this property of CTLA-4 affects both conventional T cells (Tconvs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Here, we report that CTLA-4 had significantly more potent effects on the motility and contact times of Tconvs than Tregs. This was shown firstly by anti–CTLA-4 reversal of the anti-CD3 stop-signal on FoxP3-negative cells at concentrations that had no effect on FoxP3-positive Tregs. Secondly, the presence of CTLA-4 reduced the contact times of DO11.10 x CD4+CD25− Tconvs, but not DO11.10 x CD4+CD25+ Tregs, with OVA peptide presenting DCs in lymph nodes. Thirdly, blocking of CTLA-4 with anti–CTLA-4 Fab increased the contact times of Tconvs, but not Tregs with DCs. By contrast, the presence of CD28 in a comparison of Cd28−/− and Cd28+/+ DO11.10 T cells had no detectable effect on the contact times of either Tconvs or Tregs with DCs. Our findings identify for the first time a mechanistic explanation to account for CTLA-4–negative regulation of Tconv cells but not Tregs in immune responses.

Introduction

T-cell responses require an antigen-specific signal generated by the TCR/CD3 and CD4-CD8-p56lck complexes1,2 as well as by coreceptors, such as CD28, inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS), CTLA-4, and programmed death-1 (PD-1).3,4 CTLA-4 is inhibitory as demonstrated by the phenotype of Ctla4−/− mice that develop a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by massive tissue infiltration and early lethality.5,6 CTLA-4 raises the threshold that is needed for T-cell activation by cell intrinsic and extrinsic pathways.7 Cell intrinsic mechanisms include inhibition of ZAP-70 microcluster formation,8 an altered immunologic synapse (IS),9 modulation of TCR signaling by phosphatases SHP-2 and PP2A,10,11 and interference with the expression or composition of lipid rafts on the surface of T cells.12-14 Cell extrinsic functions include the ecto-domain competition for CD28 binding to CD80/CD86,15 occupancy or removal of CD80/8616 or the release of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)17 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β).18 CTLA-4 expression is also needed for optimal suppression by regulatory T cells (Tregs).19 The external domain of CTLA-4 has been reported to mediate anergy induction, whereas its effect in reducing TCR signaling required the internal domain.20 In this context, we have shown that CTLA-4 induces T-cell motility (ie, motility activator) and limits contact times with DCs as well as affecting the migration of T cells in lymph nodes.8,21,22 Reduced contact times by CTLA-4 would be expected to limit TCR ligation events and raise the threshold for T-cell activation.21-24 The motility inducing effects of CTLA-4 have been confirmed by several laboratories in various in vivo models,25-27 and involves CTLA-4 activation of the GTP binding protein Rap1 and LFA-1 adhesion.24,28

Immune responses are regulated by a balance of inflammatory responses by conventional or responder T cells (Tconvs) and suppression by Tregs that maintain tolerance to self-antigen.29,30 Treg suppression of the in vitro proliferation of Tconvs is cell-contact–dependent.31 Further, Tregs constitutively express CTLA-4 which can be released to the cell surface and is needed for optimal suppressor function.19,32,33 In this context, it has been unclear whether CTLA-4 can reverse the stop-signal of both Tconv and Treg cells. In this study, we show that Tconvs are significantly more affected by the CTLA-4 reversal of arrest than Tregs. This was shown in responses of GFP-FoxP3–positive T cells to CTLA-4 reversal of anti-CD3 induced arrest, in a comparison of the contact times of CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ T cells from DO11.10 x Ctla4+/+ versus Ctla4−/− T cells with DCs in lymph nodes, and in the selective increase by anti–CTLA-4 Fab of contact times of Tconvs with DCs.

Methods

Cells and mice

Primary murine T cells from DO11.10 mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 2mM glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50μM 2-ME. CD4+ T cells were purified using Dynabeadsmouse CD4 (L3T4) and DetachaBeadmouse CD4 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2mM glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50μM 2-ME, 20 ng/mL recombinant murine GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL IL-4. On day 7 of culture, BMDCs were induced to mature by adding 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide to the medium. After an overnight incubation, nonadherent cells and loosely adherent proliferating BMDC aggregates were collected, washed, and replated for 1 hour at 37° C to remove contaminating macrophages. CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells were separated using a CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of both populations was greater than 95% as assessed by flow cytometry. Ctla4−/− x DO11.10 and Cd28−/− x DO11.10 Tg mice were a kind gift from Dr Arlene Sharpe (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA) and Dr Jonathan Green (Washington University of Medicine, St Louis, MO), respectively. GFP-FoxP3 mice were kindly provided by Dr Vijay Kuchroo (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA).

Antibodies and reagents

Anti–mouse CD3 (145-2C11) and anti–mouse CTLA-4 (UC10-4F10-11) were purchased from BioXCell, CFSE (carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) was from Sigma-Aldrich. OVA peptide (323-339) was purchased from Bachem. Dynabeads M-450 Epoxy, yellow-green fluorescent microspheres (505/515) and SNARF-1 were purchased from Invitrogen. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell isolation kit was bought from Miltenyi Biotec, Lab-Tek chambered coverglass were from Nunc. Anti–CTLA-4 Fab fragments were prepared using the Fab preparation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific).

Cell motility assays

Murine CD4+ T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 hours, before transfection with 2 μg CTLA-4-GFP or vector (pEGFP) per 1 × 106 cells using the Amaxa Nucleofector Kit (Lonza), as described34 (Figure 1). Cells were then maintained in culture without anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours (ie, rested) followed by analysis of motility. In experiments not involving transfection (Figures 2,Figure 3,Figure 4,Figure 5–6), 48 hour activated cells were also rested for 24 hours before use in assays. For in vitro motility assays, pre-activated GFP-FoxP3–positive and GFP-FoxP3–negative CD4-positive T cells were stimulated with either soluble isotype antibody (40 μg/mL), or with soluble anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) in the absence or presence of various soluble anti–CTLA-4 concentrations (5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL) during the time of tracking on ICAM-1-Fc (2 μg/mL) coated plates. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used to crosslink the primary anti-CD3 and CTLA-4 antibodies using a concentration ratio of 1:4 relative to the primary antibodies. Images were acquired every 10 seconds for 20 minutes. Images were processed by Zeiss LSM510 confocal software and Volocity software (Improvision).

Imaging on LN slices

Ex vivo imaging of T cells and APCs in lymph node (LN) slices was carried out as described.35,36 T cells from DO11.10 x Ctla4−/− and Ctla-4+/+ mice were initially activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 hours to induce CTLA-4 surface expression on DO11.10 x Ctla-4+/+ T cells and rested for 24 hours before use for experiments. Between 1 to 5 × 105 CFSE labeled T cells in 10 to 20 μL of RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS were plated onto the surface of each LN slice. DCs were loaded with SNARF-1 and plated at 1 × 106 cells per LN slice. In some experiments, DCs were incubated with OVA peptide before plating them on top of the slice. T-cell behavior within a LN slice was analyzed in the T-cell area, 10 to 20 μm in depth from the cut surface. Images were acquired every 10 seconds for 20 minutes. Images were processed by Zeiss LSM510 confocal software and Volocity software (Improvision). T-cell/APC interactions were then monitored by ImageJ Version 1.45 software.

Results

CTLA-4 modulates T-cell motility in LNs

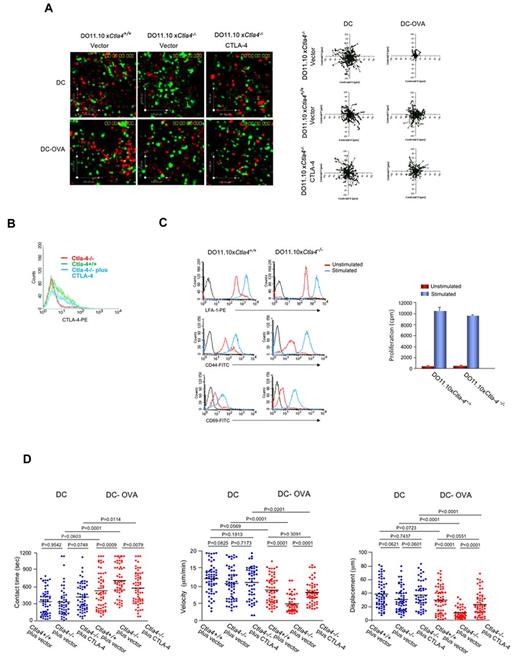

We previously showed that CTLA-4 induces T-cell motility, and reverses the “stop-signal” needed for T cell–APC conjugation.8,21,22 However, these initial studies were performed using separated primary CTLA-4–positive and –negative T cells of normal mice and cell lines.8,21,22 In a complementary approach, the motility and contact times of T cells from genetically ablated Ctla4−/− mice were contrasted with cells from Ctla4+/+ DO11.10 Tg mice in LN slices in the presence of mature bone marrow (BM)–derived DCs35,36 (Figure 1). Both sets of T cells were initially activated for 48 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 to induce CTLA-4 expression on the Ctla4+/+ T cells. Cells were then transfected with vector (pEGFP) or CTLA-4-GFP and rested for 24 hours before analysis. Mature DCs were labeled with SNARF-1 and pre-incubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA) before incubation with T cells on LN slices, as described.35 Adhesion of T cells was partly dependent on ICAM-1 as shown by a 55% reduction in binding in the presence of blocking anti–ICAM-1 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). T cells were seen to move dynamically and randomly on and within the lymph node, often entering the tissue and reappearing along the nodal surface (Figure 1A, supplemental Video 1). Tracking profiles of Ctla4−/− T cells were restricted by the presence of DC-OVA consistent with the arrest-signal (right top panels). By contrast, profiles of Ctla4+/+ T cells showed extensive migration similar to cells incubated with DCs alone (right middle panels). To confirm that the difference in migration was due to CTLA-4 expression and not to a difference in the activation status of the 2 sets of cells, Ctla4−/− T cells were transfected with CTLA-4-GFP (right bottom panels). The expression level of transfected CTLA-4 was similar to that seen with endogenous CTLA-4 on activated Ctla4+/+ T cells (Figure 1B). Significantly, CTLA-4-GFP expression in Ctla4−/− T cells was sufficient to restore migration comparable with wild-type Ctla4+/+ T cells (right bottom panels). Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− T cells also showed comparable LFA-1 (Figure 1C top left panel), CD44 (middle left panel) and CD69 (bottom left panel) expression and underwent similar proliferation induced by anti-CD3/CD28 ligation as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation (right panel). These findings indicated that the expression of CTLA-4 itself was responsible for the reversal of the TCR stop-signal.

CTLA-4 reverses TCR stop-signal and limits T cell/DC dwell-times in Ctla4+/+ DO11.10 T cells.Ctla4+/+ T cells fail to stop in response to DC-OVA peptide in contrast to Ctla4−/− T cells. GFP-vector or GFP-CTLA-4, CD4-positive T cells from Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− DO11.10 TCR Tg mice were preactivated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 hours, transfected and then rested for 24 hours. Cells were tracked for migration on LN slices as described.35 Ctla4−/− cells plus CTLA-4 represents Ctla4−/− T cells transfected with mouse GFP-CTLA-4. Ctla4−/− cells plus vector represents Ctla4−/− T cells transfected with pEGFP. T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs (see supplemental Video 1). (A) Tracing of the migration of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells on LN slices. T-cell tracks have been superimposed from their starting positions. (B) CTLA-4 expression in transfected Ctla4−/− T cells. Ctla4−/− CD4-positive T cells were transfected with CTLA-4-GFP and assessed for expression by FACS. (C) Left panel: Unstimulated or anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− DO11.10 CD4-positive T cells for 48 hours followed by resting for 24 hours were stained with anti–LFA-1-PE, anti–CD44-APC or anti–CD69-APC. Right panel: 3H-thymidine incorporation of unstimulated and anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated DO11.10 CD4-positive Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− T cells. (D) Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− DO11.10 CD4-positive T cells were seeded with SNARF-1 labeled DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Migration on LN slices was monitored over a time period of 20 minutes. Left panel: Contact times of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Middle panel: Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T-cell velocities with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Right panel: Measurements of displacement of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 6 separate experiments.

CTLA-4 reverses TCR stop-signal and limits T cell/DC dwell-times in Ctla4+/+ DO11.10 T cells.Ctla4+/+ T cells fail to stop in response to DC-OVA peptide in contrast to Ctla4−/− T cells. GFP-vector or GFP-CTLA-4, CD4-positive T cells from Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− DO11.10 TCR Tg mice were preactivated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 hours, transfected and then rested for 24 hours. Cells were tracked for migration on LN slices as described.35 Ctla4−/− cells plus CTLA-4 represents Ctla4−/− T cells transfected with mouse GFP-CTLA-4. Ctla4−/− cells plus vector represents Ctla4−/− T cells transfected with pEGFP. T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs (see supplemental Video 1). (A) Tracing of the migration of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells on LN slices. T-cell tracks have been superimposed from their starting positions. (B) CTLA-4 expression in transfected Ctla4−/− T cells. Ctla4−/− CD4-positive T cells were transfected with CTLA-4-GFP and assessed for expression by FACS. (C) Left panel: Unstimulated or anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− DO11.10 CD4-positive T cells for 48 hours followed by resting for 24 hours were stained with anti–LFA-1-PE, anti–CD44-APC or anti–CD69-APC. Right panel: 3H-thymidine incorporation of unstimulated and anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated DO11.10 CD4-positive Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− T cells. (D) Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− DO11.10 CD4-positive T cells were seeded with SNARF-1 labeled DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Migration on LN slices was monitored over a time period of 20 minutes. Left panel: Contact times of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Middle panel: Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T-cell velocities with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Right panel: Measurements of displacement of Ctla4+/+, Ctla4−/−, and GFP-CTLA-4 transfected Ctla4−/− T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 6 separate experiments.

Velocity measurements confirmed this finding (Figure 1D). For contact times, Ctla4−/− T cells showed an increase in the duration of contact from 370 seconds with DCs alone to 750 seconds with DC-OVA (P = .0001; left panel). Contrarily, Ctla4+/+ T cells increased dwell times from 350 with DCs alone to 440 seconds with DC-OVA. This difference was statistically insignificant (P = .0603). Transfection of Ctla4−/− T cells with CTLA-4-GFP reduced contact times from 750 to 575 seconds with DC-OVA (P = .0079). In terms of velocity, Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ T cells moved at 11 to 13 μm/min with DCs alone. In the presence of DC-OVA, Ctla4−/− DO11.10 T cells slowed from 10.99 to 5.14 μm/min (P < .0001). By contrast, Ctla4+/+ T cells slowed in a manner that was marginally significant from 12.12 to 9.10 μm/min (P = .0569; middle panel). Transfection of Ctla4−/− T cells with CTLA-4-GFP in turn restored motility from 4.7 to 8.0 μm/min (P < .0001). For displacement values (ie, distance traveled from point of origin), Ctla4−/− T cells showed a reduction from 38 to 10 μm (P < .0001), whereas the displacement for Ctla4+/+ T cells from 39 to 31 μm did not achieve statistical significance (P = .0723). However, transfection of Ctla4−/− T cells with CTLA-4-GFP increased displacement from 10 to 27 μm (P < .0001; right panel). Collectively, these data further indicated that CTLA-4 expression on primary T cells conferred a resistant to motility arrest induced by TCR engagement.

CTLA-4 reversal of anti-CD3 arrest occurs independently of CD28 expression

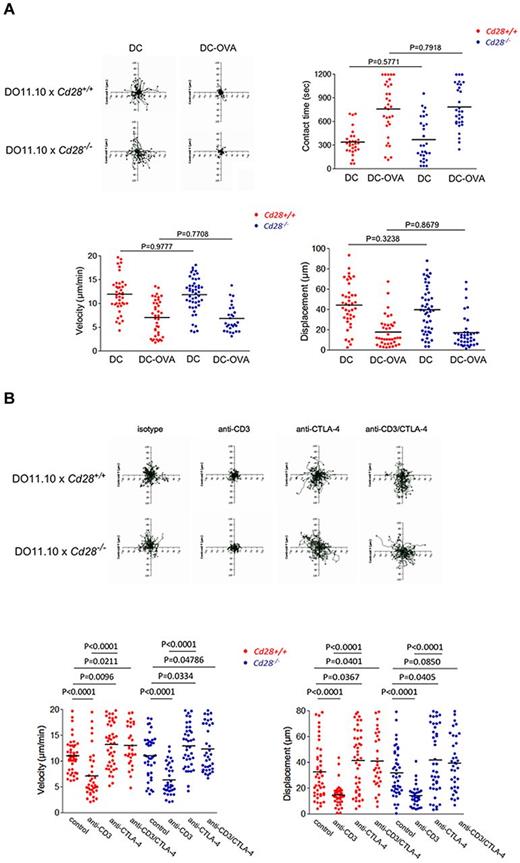

The ability of CTLA-4 to limit contact times could be related to intracellular signaling events, or indirectly be related to competition with CD28 for binding to shared ligands CD80/86. In one scenario, CTLA-4 would interfere with CD28 binding to CD80/86, and in the process indirectly interfere with CD28 regulation of contact times. This latter possibility was considered unlikely because although CD28 and CTLA-4 compete at the level of signaling at an already formed IS37 there have been no reports of CD28 potentiating T-cell contact times with DCs. However, to test this, the response of CD4+ DO11.10 T cells from Cd28−/− and Cd28+/+ mice were assessed in LN slices in the presence of DC-OVA (Figure 2A). Cells were prepared in the same manner as described for the experiments with T cells from Ctla4+/+ versus Ctla4−/− mice. However, the contact time, velocity, and displacement values showed no difference between T cells from Cd28+/+and Cd28−/− mice. Tracking profiles of individual cells showed that T cells from Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− mice both slowed in response to DC-OVA (top left panels). Dwell times increased from 356 to 777 seconds for Cd28+/+ T cells which resembled Cd28−/− T cells from 364 to 782 seconds (P = .7918; top right panel). Speeds were also similar with a change from 12.3 to 7.5 μm/min for Cd28+/+ T cells and 12.4 to 7.6 μm/min for Cd28−/− T cells (P = .7708; bottom left panel). Displacement values were comparable (bottom right panel). These data showed that the presence of CD28 had no detectable effect on the contact times with DCs, or on T-cell motilities. CTLA-4 was therefore unlikely to have reversed the stop-signal and limit T-cell contacts with DCs via an indirect effect on CD28.

The reversal of the anti-CD3 stop signal is unaffected by the presence of CD28. (A) Interaction of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/−CD4-positive T cells with DCs presenting OVA peptide. Left panel: Tracing of the migration of pre-activated Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells on LN slices. T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been pre-incubated with OVA peptide (0.5 μg/mL; DC-OVA). T-cell tracks have been superimposed from their starting positions. Right panel: Contact times of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4- positive T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Bottom left panel: Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T-cell velocities with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Bottom right panel: Measurements of displacement of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. (B) Anti–CTLA-4 reverses equally the stop-signal on both the Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells. Top panel: Tracing patterns of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells. T cells were initially activated for CTLA-4 surface expression and then rested for 24 hours before use in experiments. Cells were monitored over 20 minutes for random movement on glass slides coated with 2 μg/mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3, anti–CTLA-4, or anti-CD3/CTLA-4. Stimulation with soluble antibody isotype served as a negative control. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking (1:4 ratio to primary antibodies). Bottom left panel: measurements of velocity; right panel: measurements of displacement. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 4 separate experiments.

The reversal of the anti-CD3 stop signal is unaffected by the presence of CD28. (A) Interaction of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/−CD4-positive T cells with DCs presenting OVA peptide. Left panel: Tracing of the migration of pre-activated Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells on LN slices. T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been pre-incubated with OVA peptide (0.5 μg/mL; DC-OVA). T-cell tracks have been superimposed from their starting positions. Right panel: Contact times of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4- positive T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Bottom left panel: Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T-cell velocities with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. Bottom right panel: Measurements of displacement of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ T cells with DCs in the presence and absence of OVA peptide on LN slices. (B) Anti–CTLA-4 reverses equally the stop-signal on both the Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells. Top panel: Tracing patterns of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4-positive T cells. T cells were initially activated for CTLA-4 surface expression and then rested for 24 hours before use in experiments. Cells were monitored over 20 minutes for random movement on glass slides coated with 2 μg/mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3, anti–CTLA-4, or anti-CD3/CTLA-4. Stimulation with soluble antibody isotype served as a negative control. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking (1:4 ratio to primary antibodies). Bottom left panel: measurements of velocity; right panel: measurements of displacement. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 4 separate experiments.

To extend these observations further, we compared the effect of anti–CTLA-4 antibody on the anti-CD3 induced stop-signal of Cd28+/+ vs. Cd28−/− T cells on ICAM-1-Fc coated plates. Anti-CD3 and anti–CTLA-4 were cross-linked with rabbit anti–hamster (Figure 2B). Tracking profiles showed that both T-cell subsets exhibited random movement as shown by extensive tracks of individual cells over time (top panel). Anti-CD3 ligation caused a restricted profile indicative of stoppage, whereas coligation with anti–CTLA-4 restored tracks of both Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− T cells. Velocity measurements revealed that anti-CD3 reduced the speeds to a similar extent, from 11.2 to 7.1 μm/min for Cd28+/+ cells (P < .0001) and from 11.0 to 6.4 μm/min for Cd28−/− cells (P < .0001; left bottom panel). CTLA-4 coligation with TcR/CD3 reversed the stop-signal to a similar level, with a motility change from 7.1 to 13.3 μm/min for Cd28+/+ T cells (P < .0001) and from 6.4 to 13.0 μm/min for Cd28−/− T cells (P < .0001). No difference was noted in the displacement values for the 2 subsets (bottom right panel). This clearly showed that anti–CTLA-4 is capable of reversing the anti-CD3 stop-signal equally on both T-cell populations. Anti–CTLA-4 alone increased the motility of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− T cells to a comparable extent from 11.2 to 13.3 μm/min for Cd28+/+ T cells (P = .0096) and 11.0 to 13.0 μm/min for Cd28−/− T cells (P = .0334). Displacement measurements confirmed these findings (right panel).

CTLA-4 reversal of the TCR stop-signal preferentially affects Tconvs

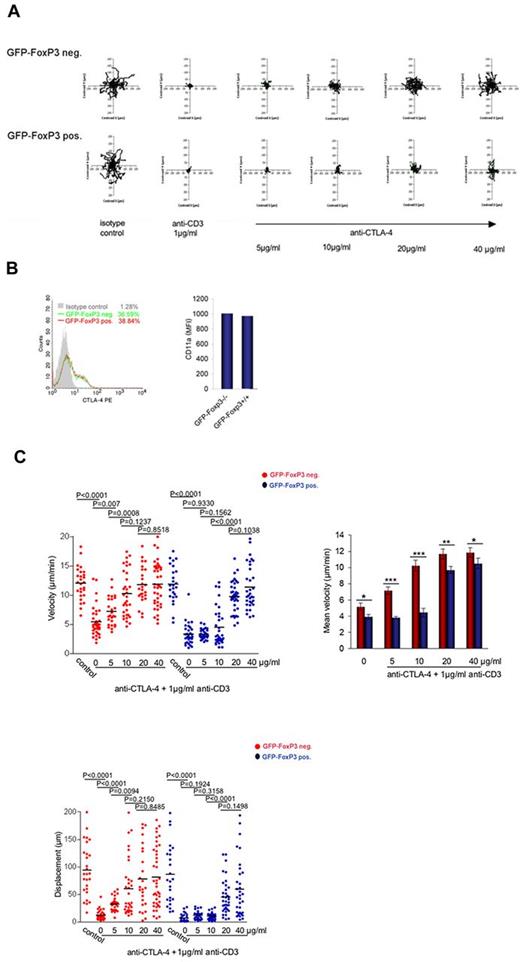

Although CTLA-4 can reverse the TCR “stop-signal” in a mixed population of CD4+ T cells,8,21 it has been unclear whether it could exert an influence equally on Tconvs and Tregs. To assess this, CD4+ T cells from GFP-FoxP3 knock-in mice were initially tracked for motility on ICAM-1-Fc coated plates in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 and/or anti–CTLA-4 cross-linked with rabbit anti–hamster (Figure 3A). As before, CD4+ T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 hours to induce CTLA-4 surface expression followed by resting for 24 hours before use in experiments. GFP-positive (Treg) and GFP-negative (Tconv) T cells were then tracked within the same population of cells. Based on tracking profiles, both subsets underwent comparable random movement in the absence of anti-CD3 (Figure 3A left top and bottom panels). Anti-CD3 arrested motility of both subsets as shown by the more restricted tracking profiles. Anti–CTLA-4 coligation with anti-CD3 reversed the arrest-signal as seen by a restoration of the movement of the GFP-FoxP3–negative Tconvs at concentrations from 5 to 20 μg/mL. By contrast, the arrest of GFP-FoxP3–positive Tregs was relatively resistant to the effects of anti–CTLA-4 (bottom panel). In terms of speed as determined by Volocity software, 5 μg/mL anti–CTLA-4 reversed the arrest-signal on GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells from 5.5 to 7.0 μm/min (P = .007), whereas the same concentration of antibody had no effect on the GFP-FoxP3–positive Treg subset (ie, 3.5 to 3.7 μm/min; P = .9330; Figure 3C top panels). Similarly, although 10 μg/mL of anti–CTLA-4 restored motility in GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells (ie, 7.0 to 10.5 μm/min; P = .0008), it had no effect on GFP-FoxP3–positive T cells (ie, 3.7 to 4.8 μm/min; P = .1562). Only at higher anti–CTLA-4 concentrations from 20 to 40 μg/mL was a reversal of the stop-signal evident in the Treg population (histogram right panel). Displacement values further emphasized this finding where 5 μg/mL anti–CTLA-4 changed the displacement of GFP-FoxP3–negative cells from 9.68 to 28.15 μm (P < .0001), although having no effect on the GFP-FoxP3–positive cells (P = .1924; bottom panel). Anti–CTLA-4 (10 μg/ml) increased displacement of GFP-FoxP3–negative cells further from 28.15 to 67.58 μm (P = .0094), although having no effect on GFP-FoxP3–positive Tregs (P = .3158). Even with 20 to 40 μg/mL anti–CTLA-4, the displacement value for Tregs was less than observed for Tconv cells. FoxP3-positive Tregs were therefore relatively resistant to the anti–CTLA-4 reversal of the arrest-signal induced by anti-CD3, when contrasted with the response of Tconvs. This occurred although the 2 T-cell subsets expressed comparable levels of surface CTLA-4 and LFA-1 (CD11a; Figure 3B). This suggested that the 2 populations differed in signals needed to reverse the stop-signal for motility, and was not merely because of a difference in the expression of surface receptors.

TCR arrested GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells are relatively resistant to the arrest reversal effects of CTLA-4. (A) Left panel: Tracing patterns of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-FoxP3-negative-CD4–positive T cells. T cells were initially activated for CTLA-4 surface expression and then rested for 24 hours before use for experiments. Cells were monitored over 20 minutes for random movement on glass slides coated with 2 μg/mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 alone, or in combination with various anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Stimulation with soluble antibody isotype served as a negative control. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking. Top panels: GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells; bottom panels: GFP-FoxP3–positive T cells. (B) CTLA-4 and LFA-1 (CD11a) are expressed at similar levels of Tconvs and Tregs. Left panel: CTLA-4–expression in GFP-FoxP3–positive and GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells. Cells were stained with CTLA-4-PE and analyzed by FACS. Right panel: Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of LFA-1 expression in FoxP3-positive and -negative T cells after activation. (C) Measurements of the velocities of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-FoxP3–negative CD4-positive T cells. Left panel: Velocity of cells were monitored on glass slides coated with 2 μg /mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 alone, or in combination with various anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking. Right panel: Histogram showing mean velocity of the 2 populations in response to different anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Bottom left panel: Measurements of displacement of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-Foxp3-CD4–negative T cells. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant; *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Data are representative of at least 3 separate experiments.

TCR arrested GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells are relatively resistant to the arrest reversal effects of CTLA-4. (A) Left panel: Tracing patterns of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-FoxP3-negative-CD4–positive T cells. T cells were initially activated for CTLA-4 surface expression and then rested for 24 hours before use for experiments. Cells were monitored over 20 minutes for random movement on glass slides coated with 2 μg/mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 alone, or in combination with various anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Stimulation with soluble antibody isotype served as a negative control. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking. Top panels: GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells; bottom panels: GFP-FoxP3–positive T cells. (B) CTLA-4 and LFA-1 (CD11a) are expressed at similar levels of Tconvs and Tregs. Left panel: CTLA-4–expression in GFP-FoxP3–positive and GFP-FoxP3–negative T cells. Cells were stained with CTLA-4-PE and analyzed by FACS. Right panel: Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of LFA-1 expression in FoxP3-positive and -negative T cells after activation. (C) Measurements of the velocities of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-FoxP3–negative CD4-positive T cells. Left panel: Velocity of cells were monitored on glass slides coated with 2 μg /mL of ICAM-1-Fc in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 alone, or in combination with various anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Rabbit anti–hamster antibody was used for crosslinking. Right panel: Histogram showing mean velocity of the 2 populations in response to different anti–CTLA-4 concentrations. Bottom left panel: Measurements of displacement of GFP-FoxP3-CD4–positive T cells and GFP-Foxp3-CD4–negative T cells. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant; *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Data are representative of at least 3 separate experiments.

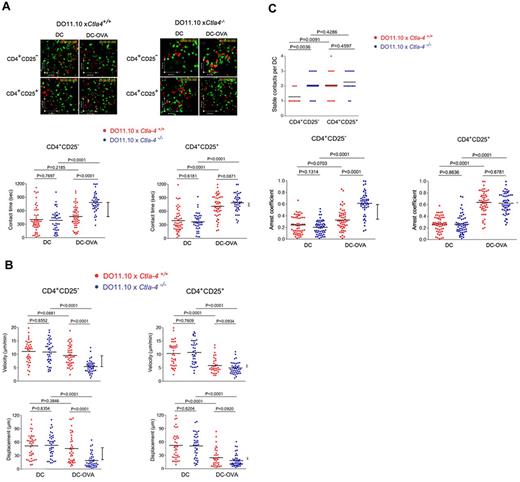

To assess responses in the context of peptide antigen presented by DCs, pre-activated CFSE labeled CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells from Ctla4+/+ and Ctla-4−/− DO11.10 Tg mice were imaged with DCs in syngeneic LNs (Figure 4). As above, CD4+ T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 hours to induce CTLA-4 surface expression followed by resting for 24 hours before use in experiments. Although naive T cells from DO11.10 mice on a Rag−/− background lack Tregs,38 the in vitro expansion of CD4+CD25+ T cells by anti-CD3/CD28 activation resulted in FoxP3 expression on more than 90% of T cells (supplemental Figure 2). This population of CD4+CD25+ T cells represents an expanded group of inducible Tregs (iTregs). Matured DCs were labeled with SNARF-1 and preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA) before incubation on LN slices. Ctla4+/+ and Ctla-4−/− CD4+CD25+/+ iTregs and CD4+CD25− Tconv cells exhibited the same random movement on surface of LNs in the presence of DCs without OVA peptide (Figure 4A; supplemental Videos 2-3). In the CD4+CD25+ iTreg population, Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ T cells showed the same increase in contact times from 370-385 to 780-820 seconds (right panel). In other words, CTLA-4 did not affect the interaction of iTregs with DCs. Within the CD4+CD25− Tconv population, Ctla4−/− T cells lacking CTLA-4 showed a similar increase in contact times from 360 to 825 seconds (P < .0001). However, by contrast, the presence of CTLA-4 prevented an increase in contact times (ie, 370 seconds to 450 seconds, P = .2185). Similar differences in the dependency of the Tconv but not the iTreg population was seen with velocity and displacement (Figure 4B). It was also reflected in a difference in the number of stable T-cell contacts with DCs (Figure 4C top panel). Stable T-cell contacts were defined as the number of T cells that bound to DCs for longer than 5 minutes. Although CD4+CD25+ Tregs with or without CTLA-4 or CD4+CD25− Tconvs lacking CTLA-4 showed an average of 2 cells/DC, the presence of CTLA-4 on the Tconvs reduced this value to 1.4 cells/DC. Similarly, a measure of the arrest coefficient showed the same pattern where the presence of CTLA-4 only affected the arrest coefficient of the Tconv cells (bottom panels). These findings clearly showed that Tconv and iTregs differ fundamentally in the response to the ability of CTLA-4 to limit contact times with DCs and increase motility.

CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs slow in response to OVA peptide in a CTLA-4–independent manner. (A) Dwell times of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− Tcons and CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ CD25− T cells from Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− x DO11.10 Tg mice were labeled with CFSE and tracked for migration on LN slices as described (see supplemental Videos 2-3).38 T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly longer contact times than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable contact times in the presence of DC-OVA. (B) Velocity and displacement of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− Tcons and CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells move significantly slower than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable velocities in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly reduced displacement compared with Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable displacement measurements in the presence of DC-OVA. (C) Stable contacts and arrest coefficients of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/−CD4+CD25− Tcons and CD4+CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Top panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly more stable contacts with DCs than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show similar behavior for stable T cell/DC interaction. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show a significant higher arrest coefficient than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show similar arrest coefficients. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant; *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments.

CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs slow in response to OVA peptide in a CTLA-4–independent manner. (A) Dwell times of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− Tcons and CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ CD25− T cells from Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− x DO11.10 Tg mice were labeled with CFSE and tracked for migration on LN slices as described (see supplemental Videos 2-3).38 T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly longer contact times than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable contact times in the presence of DC-OVA. (B) Velocity and displacement of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− Tcons and CD4+ CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells move significantly slower than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable velocities in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly reduced displacement compared with Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable displacement measurements in the presence of DC-OVA. (C) Stable contacts and arrest coefficients of Ctla4+/+ and Ctla4−/−CD4+CD25− Tcons and CD4+CD25+ Tregs on LNs in response to OVA peptide. Top panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show significantly more stable contacts with DCs than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of DC-OVA. Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show similar behavior for stable T cell/DC interaction. Bottom left panel: Ctla4−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show a significant higher arrest coefficient than Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25− T cells. Bottom right panel: Ctla4−/− and Ctla4+/+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells show similar arrest coefficients. Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant; *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments.

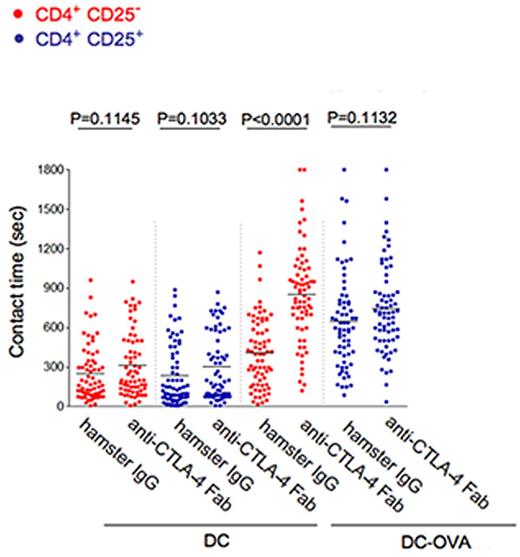

CTLA-4 blockade increases the contact times of Tconvs but not Tregs

Another approach was to use anti–CTLA-4 Fab to block CTLA-4 binding and assess the effect on the contact times of T cells with DCs (Figure 5). Anti–CTLA-4 Fab increased the mean contact times of Tconv cells with DC-OVA cells from 510 to 905 seconds (P < .0001), an effect consistent with the limitation on contact times of Tconvs with DCs by CTLA-4. The net effect on Tconvs was to achieve the same contact period observed for CD4+CD25+ Tregs. At the same time, anti–CTLA-4 Fab antibody had no effect on the contact times of the CD4+CD25+ Tregs (P = .1132). This finding strongly supported the concept that CTLA-4 limits the contact times of Tconvs but not Tregs with antigen presenting cells.

Dwell times of Tconvs versus Tregs with DCs in the presence of blocking anti–CTLA-4 Fab. CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells from DO11.10 x Ctla4+/+ mice were incubated with anti–CTLA-4 Fab, or isotype anti–hamster IgG control. After 30 minutes, contact times were measured between DCs and T cells in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Differences between the mean values were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Dwell times of Tconvs versus Tregs with DCs in the presence of blocking anti–CTLA-4 Fab. CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells from DO11.10 x Ctla4+/+ mice were incubated with anti–CTLA-4 Fab, or isotype anti–hamster IgG control. After 30 minutes, contact times were measured between DCs and T cells in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Differences between the mean values were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments.

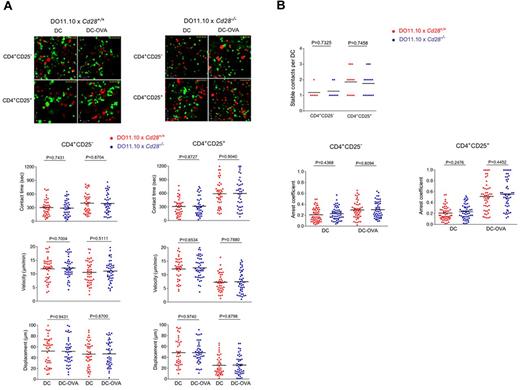

CD28 expression does not affect the contact time and motility of Tconvs or Tregs

Unlike CTLA-4, CD28 expression had no detectable effects on the contact duration of T cells with DCs or T-cell motility. Tconvs and Tregs were isolated from DO11.10 x Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− mice and analyzed for their velocity and contact times with peptide presenting DCs on LN slices (Figure 6A; supplemental Videos 4-5). The behavior of Cd28+/+ CD4+CD25− T cells regarding contact time, velocity, and displacement was comparable with Cd28+/+ CD4+CD25+T cells (left panels). Further, the greater resistance of Tregs to the reversal of the TCR induced arrest-signal was similar in the absence and presence of CD28 (right panels). Further, no difference could be observed in terms of stable contacts with DCs and arrest coefficient between CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells either expressing CD28 or being deficient of the coreceptor (Figure 6B).

CD28 expression does not affect the contact time and motility of conventional and regulatory T cells. (A) CD4+CD25− and CD4+ CD25+ T cells from DO11.10 x Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− mice show similar values for contact times, velocity, and displacement. Anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ CD25− T cells from Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− x DO11.10 Tg mice were labeled with CFSE and tracked for migration on LN slices as described (see supplemental Videos 4-5).35,36 T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs. Both Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show comparable contact times (left top panel), velocities (left middle panel), and displacement values (left bottom panel) in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA (DC-OVA). Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable contact times (right top panel), velocities (right middle panel), and displacement values (right bottom panel) in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA (DC-OVA). (B) Top panel: Stable Contact times of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells with DC-OVA. Contact times were comparable between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Bottom panels: Arrest coefficient values between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Arrest coefficient is comparable between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells (left panel) and between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells (right panel). Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments.

CD28 expression does not affect the contact time and motility of conventional and regulatory T cells. (A) CD4+CD25− and CD4+ CD25+ T cells from DO11.10 x Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− mice show similar values for contact times, velocity, and displacement. Anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ CD25− T cells from Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− x DO11.10 Tg mice were labeled with CFSE and tracked for migration on LN slices as described (see supplemental Videos 4-5).35,36 T cells were seeded with DCs alone or with DCs that had been preincubated with OVA peptide (DC-OVA). Dwell-times were followed on syngeneic LNs in the presence of SNARF-1 labeled DCs. Both Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells show comparable contact times (left top panel), velocities (left middle panel), and displacement values (left bottom panel) in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA (DC-OVA). Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells show comparable contact times (right top panel), velocities (right middle panel), and displacement values (right bottom panel) in the absence (DC) and presence of OVA (DC-OVA). (B) Top panel: Stable Contact times of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells with DC-OVA. Contact times were comparable between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Bottom panels: Arrest coefficient values between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells versus Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Arrest coefficient is comparable between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells (left panel) and between Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD4+ CD25+ T cells (right panel). Differences between means were tested using 2-tailed Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). P < .05 was considered significant. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments.

Discussion

We have previously shown that CTLA-4 can induce T-cell motility and in the process prevent or reverse the TCR stop-signal.8,21,22 The effect on motility and migration has now been reported by several other groups.25-27 In this study, we reveal a clear difference in CTLA-4 modulation of the contact times and motility of Tconvs relative to Tregs. This was shown in several assays including the finding that CTLA-4 ligation reversed the anti-CD3 induced stop-signal on FoxP3-negative cells at concentrations that had no effect on FoxP3-positive Tregs, and that the presence of CTLA-4 reduced the contact times of DO11.10 x CD4+CD25− Tconvs, but not DO11.10 x CD4+CD25+ Tregs, with OVA presenting DCs in lymph nodes. The blocking of CTLA-4 binding to CD80/86 on DCs with anti–CTLA-4 Fab alone had a clear effect in increasing the contact times of Tconvs, but not Tregs, with DCs. Our findings therefore identify for the first time a mechanistic explanation for why CTLA-4–negative regulation of Tconv cells, but not Tregs in immune responses.

Previous studies have shown that CTLA-4 selectively inhibits the function of conventional T cells,39 but by contrast, is actually required for the optimal suppressor function of Tregs.19,32 This seemingly paradoxical observation has lacked an explanation. Our findings provide a potential explanation based on the difference in CTLA-4 effects on the arrest times of the 2 subsets. In the case of Tconvs, CTLA-4 reduction of dwell times would reduce receptor ligation events resulting in the hypoactivation of cells. By contrast, the resistance of Tregs to CTLA-4 resulted in longer contact times with DCs which should lead to more efficient occupancy or removal of CD80/86 from DCs.16,40 The longer contacts were also mirrored by a greater number of Tregs bound to DCs which should also increase CD80/86 occupancy, and the possible induction of other effecter events such as the release of inhibitory factors.17 Tconvs had similar contact times in the absence of CTLA-4 (ie, on Ctla4−/−) which was reduced with the expression of CTLA-4. Although unlikely to be the sole explanation to account for the inhibitory effects of CTLA-4 on Tconvs, these new findings continue to support our model where the reversal of the stop-signal contributes to CTLA-4 inhibition of responder T cells. In our model, CTLA-4 inhibits immune response by 2 different mechanisms on Tconvs and Tregs. One pathway would limit the contact of Tconvs with DCs, whereas a second pathway would involve Tregs whose dwell times are not limited by CTLA-4, thereby allowing the coreceptor to interfere with CD80/86 presentation to CD28.

In the same vein, our findings also relate to an understanding of the basis for cell intrinsic and extrinsic regulation by CTLA-4. Cell intrinsic effects would be due to reduced dwell times leading to hypoactivation of Tconv cells. This will probably involve coreceptor signaling as evidenced by the fact that anti–CTLA-4 cross-linking alone can induce motility. In addition, the blockade of CTLA-4 binding to CD80/86 by anti–CTLA-4 Fab increased dwell times of Tconvs with DCs (Figure 5). Additional hyposignaling in Tregs (independent of our effects on dwell times) might also contribute to cell intrinsic regulation.20 By contrast, cell extrinsic effects would be due to Tregs, and their longer contact times that lead to CD80/86 occupancy or removal. The basis for the resistance of the Treg population to the reversal effects of CTLA-4 is unclear. They were not completely resistant to CTLA-4 as shown by high dose anti–CTLA-4 (ie, 20-40 μg/mL) reversal of the anti-CD3 stop-signal. The difference in sensitivity may be because of altered CTLA-4 signaling, or other intracellular mechanisms that are needed for the adhesion or motility of Tregs versus Tconvs. Studies are currently underway to uncover signaling differences between the subsets that might account for the difference in CTLA-4 mediated effects on contact times.

Our study also excludes the possibility that the observed effects of CTLA-4 on contact times are indirectly related to competition with CD28 for binding to CD80/86. In keeping with the absence of reports in the literature implicating CD28 in the modulation of T-cell contact times with DCs, we could find no evidence that contact times per se were regulated by CD28. No differences in contact times, motility, displacement or arrest coefficients were evident in the comparison of CD4+ DO11.10 T cells from Cd28−/− and Cd28+/+ mice. The involvement of CD28 in T-cell biology therefore seems more related to signaling events and the formation of the immunologic synapse in already formed T cell–DC conjugates.3,41,42 We and others have shown that CD28 can enhance signaling via the binding to intracellular proteins, such as phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI 3K),43 Grb-2,44 and protein kinase C θ.45 CTLA-4 can also alter the spatiotemporal distribution of CD28 during conjugate formation.46

Lastly, our findings could potentially explain a report from the Bluestone laboratory showing that anti–CTLA-4 blockade failed to reverse the dwell times of tolerized islet antigen-specific T cells.47 It is conceivable that certain tolerized T cells behave like Tregs in their resistance to CTLA-4 arrest reversal. In addition, our findings are consistent with aspects of a recent report from Tai et al who found that Treg suppression required only the external domain of CTLA-4, whereas TCR hyposignaling was dependent on its internal domain.20 Our findings may also have relevance to the use of anti–CTLA-4 (ipilimumab and tremelimumab) in clinical settings.48-50 Anti–CTLA-4 antibodies can induce tumor regression by having effects on both Tconvs and Tregs.50 Further studies will be needed to explore the full range of effect of anti–CTLA-4 therapy in the modulation of immune function in different clinical settings.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Arlene Sharpe for the kind gift of Ctla4−/− x DO11.10 mice (PPG National Institutes of Health P01 AI56299).

C. E. Rudd was supported by a Program Grant and holds a Principal Research Fellow Award (PRF) from the Wellcome Trust.

National Institutes of Health

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: Y.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; H.S. performed experiments, contributed to paper preparation, and wrote parts of the paper; and C.E.R. directed the study and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Helga Schneider, University of Cambridge, Dept of Pathology, Cell Signaling Section, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1QP, United Kingdom; e-mail: hs383@cam.ac.uk.