Abstract

The early blood vessels of the embryo and yolk sac in mammals develop by aggregation of de novo–forming angioblasts into a primitive vascular plexus, which then undergoes a complex remodeling process. Angiogenesis is also important for disease progression in the adult. However, the precise molecular mechanism of vascular development remains unclear. It is therefore of great interest to determine which genes are specifically expressed in developing endothelial cells (ECs). Here, we used Flk1-deficient mouse embryos, which lack ECs, to perform a genome-wide survey for genes related to vascular development. We identified 184 genes that are highly enriched in developing ECs. The human orthologs of most of these genes were also expressed in HUVECs, and small interfering RNA knockdown experiments on 22 human orthologs showed that 6 of these genes play a role in tube formation by HUVECs. In addition, we created Arhgef15 knockout and RhoJ knockout mice by a gene-targeting method and found that Arhgef15 and RhoJ were important for neonatal retinal vascularization. Thus, the genes identified in our survey show high expression in ECs; further analysis of these genes should facilitate our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of vascular development in the mouse.

Introduction

The development of the vascular system is one of the earliest events in organogenesis. Soluble factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins, fibroblast growth factors, and WNTs are crucial in inducing hematopoietic, endothelial, and cardiovascular progenitors.1–4 Recent studies have shown that mesodermal cells positive for Flk1 (vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGF-R2) are multipotent and can differentiate into endothelial, hematopoietic, smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes in an in vitro embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation model as well as during development.5–9 The existence of the hemangioblast, a bipotential precursor for hematopoietic and endothelial cells (ECs), is supported by the evidence that many genes are shared by the 2 lineages and that both the hematopoietic and angioblastic lineages are affected in Flk1-deficient embryos.10 Indeed, blast colony-forming cell, a progenitor cell capable of differentiating into 2 lineages, is present during ES differentiation and in mouse embryos.11,12 After differentiation, Flk1 is down-regulated in hematopoietic but not endothelial lineages.13

Vascular development in the mouse is strongly influenced by the dosage of VEGF-A; haploinsufficiency of VEGF-A results in embryonic lethality because of abnormal vascular development.14,15 Flk1 expression level is also important for proper vascular development, because Flk1 expression levels differ in specific EC types such as tip and stalk cells in the developing retina, and relative expression levels affect the positioning of ECs.16

Many of the events that occur during the normal progression of vascular development in the embryo are recapitulated in adults when neoangiogenesis occurs. Most notably, many tumors promote their own growth and disperse to form metastases by recruiting host blood vessels to grow into the vicinity of the tumor. In the adult, although Flk1 is expressed at low or moderate levels in normal vascular beds, it is increased in the neovasculature associated with tumor formation.17 VEGF-A signaling constitutes the dominant regulatory pathway for tumor angiogenesis.17 The humanized monoclonal anti–VEGF-A Ab bevacizumab (Avastin) provides an overall survival benefit for patients with colon cancer when combined with chemotherapy,17 thus validating angiogenesis inhibition as an effective anticancer strategy. However, progressive and refractory disease often supervenes in patients, perhaps mediated by VEGF resistance via the production of alternative angiogenic mediators, such as fibroblast growth factors, and reactivation of tumor angiogenesis.18 Therefore, identification of new molecules involved in vascular development should lead to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of vascular development as well as the establishment of more-effective approaches for treating conditions such as cancer that depend on angiogenesis.

Here, we performed a microarray analysis and identified 184 genes that are highly expressed in developing ECs and are potentially involved in vascular development. In situ hybridization analysis confirmed that Arhgef15, Arap3, Gpr116, Gpr182, Tmem204, and Plvap are expressed in developing ECs. Knock-down experiments with small interfering RNA (siRNA) for 22 human orthologs showed that 6 of these genes play a role in tube formation in HUVECs. Furthermore, we created Arhgef15 knockout (KO) and RhoJ KO mice with the use of a gene-targeting protocol and found that both Arhgef15 and RhoJ are important for neonatal retinal vascularization. Taken together, the transcriptome of developing ECs described in this study will provide us with an increased understanding of the molecular background of vascular system development.

Methods

Mice

The generation of Flk1+/GFP knock-in mice has been described previously.19 In brief, GFP cDNA (Clontech) was introduced into the first exon of the Flk1 gene to substitute for endogenous Flk1 expression. The mice were maintained on an ICR genetic background. Arhgef15 KO mice and RhoJ KO mice were created with the use of Arhgef15-lacZ knock-in ES cells (Arhgef15tm1(KOMP)Vlcg, clone 10757B-C6) and RhoJ-ires-lacZ knock-in ES cells (Rhojtm1a(KOMP)Wtsi, clone EPD0234_2_H08), respectively, purchased from the KOMP repository (www.komp.org). The ES cells were injected into blastocysts from C57B6/J mice to produce chimeric mice, which were crossed with wild-type (WT) C57B6/J mice to establish a heterozygous line. This study was approved and conducted in accordance with the Regulations for Animal Experimentation of the University of Tsukuba.

Purification of ECs

Flk1+/GFP embryos were dissected out at 8.5 days after coitus (dpc) and treated with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich). Strongly GFP+ cells, which include abundant numbers of ECs, were sorted by a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences), fluorescence-activated cell sorter in the flow cytometric facility.

Microarray analysis

WT, Flk1+/GFP, and Flk1 KO embryos proper (fetuses), at the 3-4 somite stage before the start of circulation, were dissected out at 8.5 dpc and genotyped noninvasively with the use of their GFP expression pattern. Flk1+/GFP embryos show specific fluorescence in blood islands and vascular ECs, including the yolk sac vascular network and dorsal aorta, whereas Flk1 KO embryos lack a signal in the dorsal aorta and yolk sac regions (Figure 1). The embryos proper were free of yolk sac and allantois. After homogenization, total RNAs were purified with an RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN). cDNAs were hybridized on the GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix). After washing, the arrays were treated with streptavidin-PE and analyzed on a scanner. GeneSpring GX 7.3.1 and GeneSpring GX 10 were used for the gene expression analysis. Transcripts with low expression levels (< 25% of the median gene expression value in WT embryos) and with frequent miss hybridizations (> 2 absent Flags among the samples) were not analyzed further. Transcripts that showed a > 2-fold reduction in expression in Flk1 KO embryos compared with WT embryos were extracted. In addition, transcripts that showed a > 3-fold increase in expression in the ECs that had undergone FACS compared with WT embryos were extracted. The transcript list contained 264 transcripts, including expressed sequence and transcribed locus. A total of 184 genes harboring open-reading frame are included in the transcript list (expressed sequence and transcribed locus were excluded). The location (cellular localization) and type (function) of the genes were classified by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software and/or public database search. All microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE37431.

We identified 158 human genes that are orthologous to the 184 mouse genes with the use of the GeneSpring GX10 software; the levels of expression of these human genes in VEGF-A–treated HUVECs were compared with information from a public microarray database (GSE1077820 ) in combination with GeneSpring GX 10 software.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs purified from the ECs, Flk1 KO embryos, WT embryos, HUVECs, and 293T cells that had undergone FACS were used to generate cDNA with the use of the Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN). Real-time PCR was performed with the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System (TaKaRa Bio Inc) and SYBR Premix EX Taq II (TaKaRa Bio Inc). Relative cDNA amounts were calculated with the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System Software (TaKaRa Bio Inc) and normalized against expression of Hprt. Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

cDNA clones

We obtained the cDNA clone 6430550H21 (GenBank #NM_172930, contains the 3′ untranslated region [UTR] of Fam70a) from Riken,21 and clone F830224M15 (GenBank #AK157580, contains 3′ UTR of She) from Open Biosystems. IMAGE clone 30099512 (GenBank #BC013517, contains the 3′ UTR of Plvap) and clone 6844583 (GenBank #BC089365, contains 3′ UTR of Arhgef15) were obtained from Open Biosystems.

In situ mRNA hybridization and IHC

Whole-mount in situ mRNA hybridization was performed as described previously.22 Primer sequences for cRNA probe synthesis are listed in supplemental Table 2. Whole-mount IHC with anti–PECAM-1 (MEC13.3; BD Biosciences), anti-GFP (MBL Co Ltd) and anti-Tie2 (TEK4; eBioscience) was performed as described previously.23

Tumor implantation

Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) tumors were created as previously described.24 In brief, 1.0 × 106 LLC cells in 10 μL of PBS were injected subcutaneously into 10-week-old Arhgef15 KO mice and WT littermates. The tumor volumes were evaluated from day 6 to day 10; the tumors were removed from the mice on day 10 and weighed.

X-gal staining

Whole-mount embryos were subjected to X-gal staining as previously described.10 Briefly, the embryos were fixed in glutaraldehyde solution for 10 minutes and were incubated with X-gal solution (25 mg/mL X-gal in dimethylformamide diluted in 2mM MgCl2, 0.01% deoxycholate, 0.02% Nonidet P40, 0.21% potassium ferricyanide, 0.164% potassium ferrocyanide, and PBS) at 37°C for between 4 and 12 hours, depending on levels of LacZ activity.

Tube formation assay of HUVECs

The tube formation assay was performed with HUVECs maintained in 12-well culture plates coated with Matrigel (Becton Dickinson), in a total volume of 200 μL/well. The Matrigel was allowed to solidify at 37°C for 3 hours, after which time 2 × 104 HUVECs that had been transfected with siRNAs listed in supplemental Table 3 were added to each well. VEGF-A (100 ng/mL) was also added to the wells at this time. After 16 hours, the capillaries were observed with a BioRevo inverted microscope (Keyence), and relative tube lengths, branch points and vessel area from randomly chosen fields were quantified with BZ-Analyzer software (Keyence).

Retinal whole-mount immunostaining

IHC of retinal whole mounts was performed as previously described.25 For the BrdU incorporation assay, 100 μg of BrdU/g of body weight (BD PharMingen) dissolved in sterile PBS was injected intraperitoneally 2.5 hours before killing. Isolated retinas were stained with a BrdU IHC system (Calbiochem). Two primary Abs were used, hamster anti-CD31 (2H8; Chemicon) or Collagen IV (Cosmo Bio); these were detected with DyLight549/DyeLight649-conjugated IgGs (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc) as the secondary Abs. In some experiments, blood vessels and monocyte-lineage cells were simultaneously visualized with biotinylated isolectin B4 (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by fluorescent streptavidin conjugates (Molecular Probes). Fluorescent images (Figures 6E-N, 7A-H) were obtained using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000-D; Olympus) at room temperature. Scanning was performed in sequential laser emission mode to avoid scanning at other wavelengths. The images in Figures 6G through N, 7C through H, and supplemental Figure 7 were digitally recorded with a high magnification objective lens (40×/1.3 NA oil objective) to minimize their pseudo-positive detection of the neighboring layers, while the other images (Figures 6E-F, 7A-B) were scanned with a low magnification lens (4×/0.1 NA). FV10-ASW Viewer 3.0 software (Olympus) was used to process the images (brightness and contrast), and export them as .jpg format. For image acquisition of samples stained with X-gal and Isolectin (Figure 6A-C), an inverted microscope (CKX41; Olympus) equipped with an objective lens (20×/0.4 NA) and a digital camera (DP20; Olympus) were used at room temperature. For constructing merged images, 2 images were overlaid using Adobe Photoshop CS2 and were exported as .jpg format. Quantification of substances of interest was performed in fields of view per sample in each scanned image with a high magnification objective lens (40×/1.3).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means and SEs. Differences were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

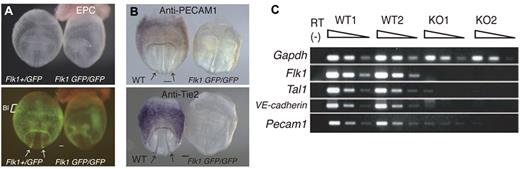

Genome-wide identification of EC-enriched genes expressed in embryos 8.5 dpc

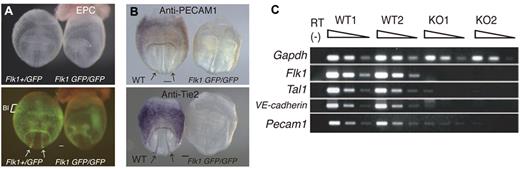

WT and Flk1 KO embryos proper were genotyped noninvasively and then used to survey genes that are expressed abundantly in ECs at 8.5 dpc, a developmental stage with a high rate of angiogenesis (Figure 1A). The primitive hematopoietic cells, which first arise in the yolk sac blood island regions, start to migrate into the embryo proper at approximately the 4-8 somite pair stage.26 Thus, WT embryos proper (3-4 somite stage) at 8.5 dpc had endothelial but not hematopoietic cells, whereas the Flk1 KO embryos proper had neither cell type. This suggests the possibility that EC-enriched genes could be identified by comparing the gene expression profiles in these 2 genotypes. Indeed, expression of the proteins PECAM-1 and Tie2 was markedly reduced in Flk1 KO embryos (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1), consistent with a previous report.10 mRNA expression of endothelial markers such as VE-cadherin, Pecam1, and others was also markedly reduced in the Flk1 KO embryo proper (Figure 1C).

Flk1 KO mice are deficient in vascular ECs. (A) Flk1+/GFP and Flk1 GFP/GFP embryos at 8.5 dpc; (top) bright field images and (bottom) fluorescent images. EPC indicates ectoplacental cone; and BI, blood island. Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (B) Reduced expression of the PECAM1 and Tie2 proteins in Flk1 KO embryos. Whole-mount IHC shows PECAM1 and Tie2 are expressed in ECs of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac of WT but not Flk1 KO embryos. Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. (C) Reduced expression of endothelial marker mRNAs, such as VE-cadherin and Pecam1, in Flk1 KO embryos at 8.5 dpc. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed on serially diluted cDNAs from WT and Flk1 KO embryos proper. Images were captured with a Leica DC500 CCD camera attached to a Leica MZ FLIII microscope (Plan APO 1.0/0.125 NA lens).

Flk1 KO mice are deficient in vascular ECs. (A) Flk1+/GFP and Flk1 GFP/GFP embryos at 8.5 dpc; (top) bright field images and (bottom) fluorescent images. EPC indicates ectoplacental cone; and BI, blood island. Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (B) Reduced expression of the PECAM1 and Tie2 proteins in Flk1 KO embryos. Whole-mount IHC shows PECAM1 and Tie2 are expressed in ECs of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac of WT but not Flk1 KO embryos. Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. (C) Reduced expression of endothelial marker mRNAs, such as VE-cadherin and Pecam1, in Flk1 KO embryos at 8.5 dpc. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed on serially diluted cDNAs from WT and Flk1 KO embryos proper. Images were captured with a Leica DC500 CCD camera attached to a Leica MZ FLIII microscope (Plan APO 1.0/0.125 NA lens).

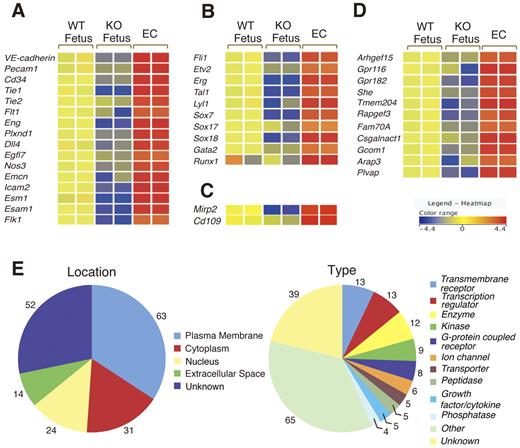

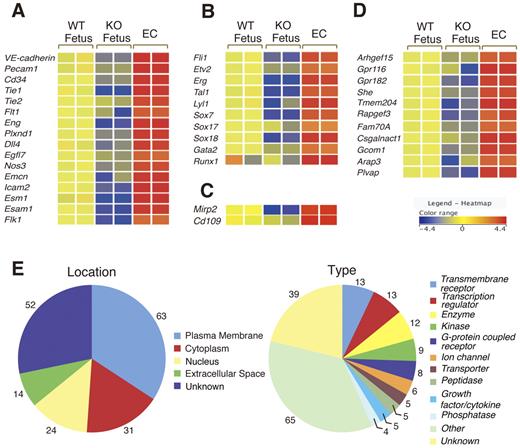

To identify genes potentially involved in vascular development, we performed microarray analysis of > 39 000 sequence tags, which include > 34 000 genes in Flk1 KO embryos proper at 8.5 dpc. The ratios of relative gene expression levels in Flk1 KO versus WT embryos proper were calculated. We identified and extracted 318 transcripts with a > 2-fold decrease in their expression levels in Flk1 KO embryos proper (data not shown). These transcripts included VE-cadherin, Pecam1, Tie1, Tie2, Cd34, and other well-known endothelial markers (data not shown), suggesting our analytical method could be used to search for EC-enriched genes. To improve the efficiency of the screen, ECs purified from embryos at 8.5 dpc were used for a comparison of gene expression profiles. Because ECs show high Flk1 expression at 8.5 dpc,13 a population of high Flk1+ cells (∼ 6% in total) was sorted from Flk1+/GFP embryos (supplemental Figure 2). Quantitative RT-PCR showed that endothelial marker genes, such as VE-cadherin and Pecam1, were expressed at a > 10-fold higher level in the Flk1-high cells compared with the WT embryo proper, indicating that the cell fraction was highly enriched for ECs (supplemental Figure 2). Using this enriched EC fraction, we obtained 264 transcripts that showed a > 3-fold up-regulation in ECs compared with the WT embryo proper (supplemental Table 4). The 264 transcripts contained 184 genes with an open-reading frame (supplemental Table 4). This group included most, if not all, known genes for EC surface molecules such as VE-cadherin, Pecam1, Endoglin, Tie1, Tie2, Flt1, Endomucin, and Cd34, indicating that the endothelial surface markers were highly enriched. Although the list also contained the transcription factors Tal1, Lyl1, Gata2, Runx1, Sox,7,17,18 and Ets [Fli1, Etv2(Er71), Erg], some of these are known to be expressed in developing ECs. Gene ontology analysis indicated that, in addition to these 10 DNA-binding transcription factors, another 14 genes were classified as “nucleus” (Figure 2E; supplemental Table 4), suggesting that they could potentially be involved in vascular development, endothelial-specific gene transcription, and leukemia. The gene list also contained Mirp2 and Cd109, which are highly expressed in tumor endothelium but not normal endothelium in the adult,27,28 suggesting a potential similarity between angiogenesis during development and tumor angiogenesis. We also identified genes that have not previously been characterized as up-regulated in developing ECs (see below).

Summary of the microarray analysis on WT fetus and Flk1 KO embryos (KO fetus) and ECs. (A) Expression of cell surface marker genes. Most of the putative EC surface markers were present among the 184 genes obtained. The relative intensities of gene expression are shown in the heat map. (B) Expression of transcription factors Ets (Fli1, Etv2, Erg), bHLH (Tal1, Lyl1), Sox (Sox7, Sox 17, and Sox18), Gata2, and Runx1. (C) Expression of tumor endothelial markers. Mirp2 and Cd109 showed high expression in ECs. (D) Expression of genes not previously studied as endothelial-specific genes during early vascular development. These genes were down-regulated in Flk1 KO embryos. (E) Location and motif classification of the 184 genes obtained in the microarray analysis by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis.

Summary of the microarray analysis on WT fetus and Flk1 KO embryos (KO fetus) and ECs. (A) Expression of cell surface marker genes. Most of the putative EC surface markers were present among the 184 genes obtained. The relative intensities of gene expression are shown in the heat map. (B) Expression of transcription factors Ets (Fli1, Etv2, Erg), bHLH (Tal1, Lyl1), Sox (Sox7, Sox 17, and Sox18), Gata2, and Runx1. (C) Expression of tumor endothelial markers. Mirp2 and Cd109 showed high expression in ECs. (D) Expression of genes not previously studied as endothelial-specific genes during early vascular development. These genes were down-regulated in Flk1 KO embryos. (E) Location and motif classification of the 184 genes obtained in the microarray analysis by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis.

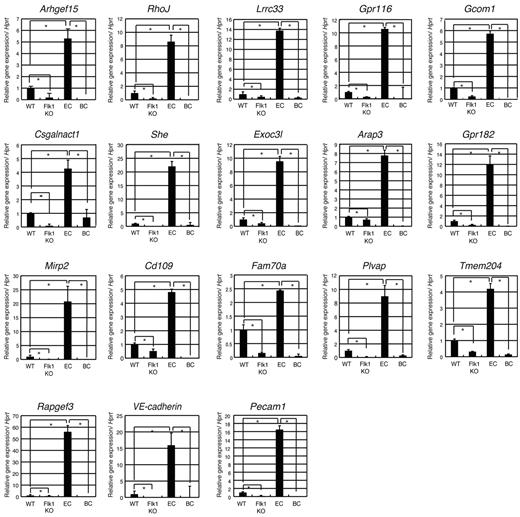

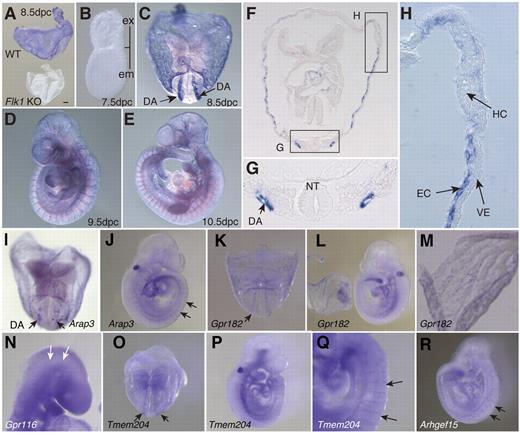

Expression of candidate genes in the mouse embryo

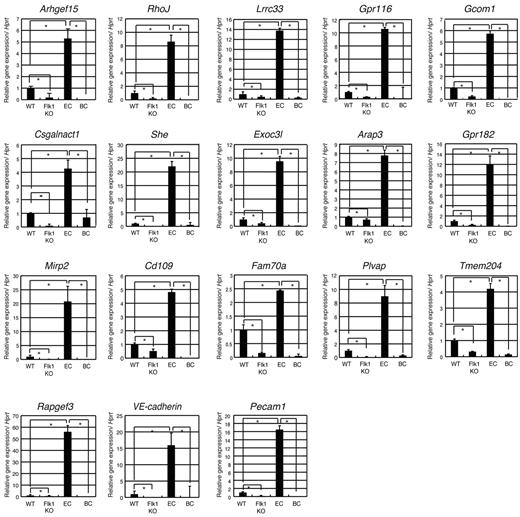

We performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis to characterize genes that have not previously been considered as important for developing ECs (Figure 3). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis clearly showed that Arhgef15, RhoJ, Lrrc33, Gpr116, Gcom1, CSgalnact, She, Exoc3l, Arap3, Gpr182, Mirp2, Cd109, Fam70a, Plvap, Tmem204, and Rapgef3 were highly expressed in the developing ECs (Figure 3). Whole-mount in situ mRNA hybridization analysis on embryos at 8.5-10.5 dpc was performed for 32 genes to obtain a more precise understanding of their expression patterns (Figure 4; data not shown). Although the protein Plvap is an essential component of stomatal and fenestral diaphragms of ECs,29–32 the pattern of expression of Plvap during embryogenesis is not known. We found that Plvap was highly expressed at the dorsal aorta and yolk sac of WT embryos at 8.5 dpc but not in Flk1 KO embryos (Figure 4A,C,F-H). Because vascular smooth muscle cells do not cover the endothelial layer at 8.5 dpc,33,34 then Plvap must be expressed at the endothelial layer of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac but not the smooth muscle layer. Plvap was not expressed in either primitive hematopoietic cells or the visceral endoderm (Figure 4H). Plvap was not expressed at 7.5 dpc, indicating that the gene is expressed in differentiated ECs but not in EC progenitors (Figure 4B). Plvap was also expressed in ECs of the dorsal aorta and intersomitic vessel of embryos at 9.5 and 10.5 dpc (Figure 4D-E).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of endothelial markers and novel genes in WT, Flk1 KO embryos, and ECs. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that Arhegf15, RhoJ, Lrrc33, Gpr116, Gcom1, CSgalnact1, She, Exoc3l, Arap3, Gpr182, Mirp2, Cd109, Fam70a, Plvap, Tmem204, and Rapgef3 were down-regulated in Flk1 KO embryos proper and were highly expressed in developing ECs (Flk1 GFP high cells), but not in hematopoietic cells. VE-cadherin and Pecam1 are endothelial markers. BC indicates blood cells.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of endothelial markers and novel genes in WT, Flk1 KO embryos, and ECs. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that Arhegf15, RhoJ, Lrrc33, Gpr116, Gcom1, CSgalnact1, She, Exoc3l, Arap3, Gpr182, Mirp2, Cd109, Fam70a, Plvap, Tmem204, and Rapgef3 were down-regulated in Flk1 KO embryos proper and were highly expressed in developing ECs (Flk1 GFP high cells), but not in hematopoietic cells. VE-cadherin and Pecam1 are endothelial markers. BC indicates blood cells.

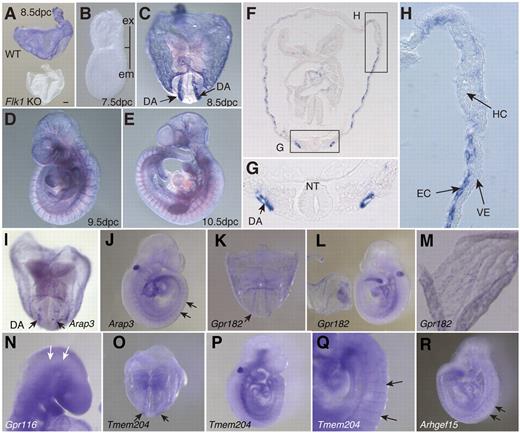

Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis.Plvap mRNA expression in WT and Flk1 KO embryos isolated at 8.5 dpc (A). WT embryo at 7.5 dpc (B), 8.5 dpc (C), 9.5 dpc (D), and 10.5 dpc (E) Scale bar indicates 100 μm. Ex indicates extraembryonic region; and em, embryonic region. (F) Transverse section of embryo 8.5 dpc. (G) Enlarged image of region indicated by rectangular box in panel F. DA indicates dorsal aorta; and NT, neural tube. (H) Enlarged image of region indicated by rectangular box in panel F. HC indicates primitive hematopoietic cells; and VE, visceral endoderm. (I-J) Arap3 at 8.5 and 9.5 dpc, respectively. (K-L) Gpr182 at 8.5 and 9.5 dpc, respectively. (M) Strong expression of Gpr182 in the yolk sac at 8.5 dpc. (N) Gpr116 at 9.5 dpc. (O-Q) Tmem204 at 8.5 dpc (O) and 9.5 dpc (P). High magnification images of intersomitic vessels (Q) of embryo at 9.5 dpc. (R) Lateral view of Arhgef15 at 9.5 dpc. Images (A-R) were captured with a Leica DC500 CCD camera attached to a Leica MZ FLIII microscope (Plan APO 1.0/0.125 NA lens) and with IM50 Imaging Manager.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis.Plvap mRNA expression in WT and Flk1 KO embryos isolated at 8.5 dpc (A). WT embryo at 7.5 dpc (B), 8.5 dpc (C), 9.5 dpc (D), and 10.5 dpc (E) Scale bar indicates 100 μm. Ex indicates extraembryonic region; and em, embryonic region. (F) Transverse section of embryo 8.5 dpc. (G) Enlarged image of region indicated by rectangular box in panel F. DA indicates dorsal aorta; and NT, neural tube. (H) Enlarged image of region indicated by rectangular box in panel F. HC indicates primitive hematopoietic cells; and VE, visceral endoderm. (I-J) Arap3 at 8.5 and 9.5 dpc, respectively. (K-L) Gpr182 at 8.5 and 9.5 dpc, respectively. (M) Strong expression of Gpr182 in the yolk sac at 8.5 dpc. (N) Gpr116 at 9.5 dpc. (O-Q) Tmem204 at 8.5 dpc (O) and 9.5 dpc (P). High magnification images of intersomitic vessels (Q) of embryo at 9.5 dpc. (R) Lateral view of Arhgef15 at 9.5 dpc. Images (A-R) were captured with a Leica DC500 CCD camera attached to a Leica MZ FLIII microscope (Plan APO 1.0/0.125 NA lens) and with IM50 Imaging Manager.

Arap3 (Centd3) encodes an Arf-GAP that contains a RhoGAP domain, an ankyrin repeat, and a PH domain 3.35 Arap3 has been reported to regulate Arf6-dependent membrane ruffling.36 We found that Arap3 was expressed in ECs of the dorsal aorta and intersomitic vessels (Figure 4I-J); Arap3 may, therefore, be involved in angiogenesis by regulating Arf6-dependent membrane protrusion in ECs.

The adrenomedullin receptor Gpr182, a member of the G protein–coupled receptor family, was expressed in ECs of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac at 8.5 dpc (Figure 4K-L). The observed expression patterns indicate that Gpr182 was expressed preferentially in the yolk sac ECs at 9.5 dpc (Figure 4M). Because adrenomedullin is known to be an angiogenic factor,37 Gpr182 expression in developing ECs may be important for adrenomedullin-dependent angiogenesis. We also investigated Gpr116, another member of the G protein–coupled receptor family. Bioinformatics analysis of publicly available microarray data from Wallgard et al suggested that Gpr116 is expressed in microvascular ECs,38 although the exact spatiotemporal expression pattern was not specified. Our in situ hybridization analysis indicated that Gpr116 was expressed in the ECs at 9.5 dpc (Figure 4N).

Tmem204 is a 4 transmembrane–spanning protein that is induced at the mRNA level by hypoxic treatment and functions as an adherens junction protein.39 Tmem204 was found to be expressed in the ECs of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac (Figure 4O-Q). Our mRNA in situ hybridization analysis indicated that Tmem204 was highly expressed in a part of the intersomitic vessels but weakly in the dorsal aorta (Figure 4O-Q), suggesting that Tmem204 is highly expressed at the location where angiogenesis is actively occurring.

Arhgef15/Vsm-Rhogef is a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Ogita et al identified Arhgef15 as a novel Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells but not ECs of the adult mouse.40 Arhgef15, however, was clearly expressed in the ECs of the dorsal aorta and yolk sac at 8.5 dpc as well as ECs at intersomitic vessels and dorsal aorta at 9.5 dpc (Figure 4R).

Expression of genes in human ECs

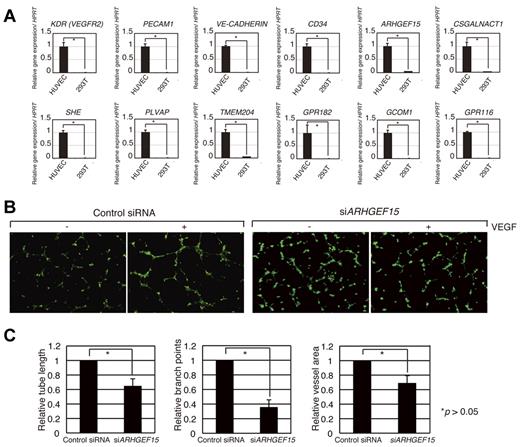

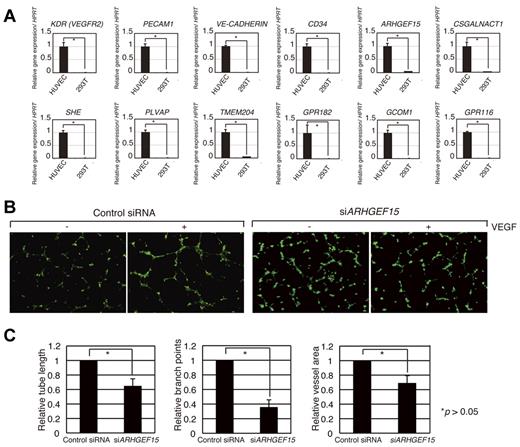

Although our analysis identified genes expressed in developing ECs of the mouse, it was not clear whether these genes also played a role in angiogenesis in human ECs. To examine this question, we first surveyed the human genome for genes with orthology to the 184 mouse genes and identified 158 candidate genes (supplemental Figure 3A). We found that 124 of these human genes showed significant expression in HUVECs. To investigate whether the expression of these human genes was influenced by VEGF-A signaling, we examined their levels of expression with the use of information available in a public microarray database and analysis with GeneSpring software (supplemental Figure 3A). Delta-like 4 (Dll4), a Notch ligand is known to be induced by VEGF-A signaling41 and is induced in the experiment20 (supplemental Figure 3B). The levels of 158 human candidate gene expressions showed dynamic changes with time after the addition of VEGF-A. Approximately 30 genes showed significant induction or suppression after 360 minutes of VEGF-A treatment (supplemental Figure 3A), indicating that they may be controlled by VEGF-A signaling. We also performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis and confirmed that some of these genes were expressed in HUVECs (Figure 5A; data not shown). Therefore, we designed siRNA knockdown oligonucleotides for 22 human orthologous genes that are expressed in HUVECs (supplemental Figure 4). The control siRNA oligonucleotide did not disturb VEGF-dependent tube formation in the HUVECs; however, siRNAs for ARHGEF15, RHOJ, LRRC33, GPR116, GCOM1, and EXOC3L reduced the ability for vascular network formation, indicating that these genes play important roles in tubular network formation in HUVECs (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figure 5).

Functional screening in HUVECs of human genes contributing to angiogenesis. (A) Expression of ARHGEF15, CSGALNACT1, SHE, PLVAP, TMEM204, GPR182, GCOM1, and GPR116 in HUVECs. KDR, PECAM1, VE-CADHERIN, and CD34 are endothelial markers. (B) Knockdown of ARHGEF15 mRNA inhibits tube formation in HUVECs. A control siRNA oligonucleotide did not affect VEGF-dependent tube formation of HUVECs; however, siRNA for ARHGEF15 reduced the ability to form a vascular network. (C) Quantification of relative tube length, branch points, and vessel area in control and knockdown HUVECs. Images (B) were captured with a Keyence BioRevo microscope (Plan Fluor 10×/0.30 NA lens) and with BZ-II Viewer.

Functional screening in HUVECs of human genes contributing to angiogenesis. (A) Expression of ARHGEF15, CSGALNACT1, SHE, PLVAP, TMEM204, GPR182, GCOM1, and GPR116 in HUVECs. KDR, PECAM1, VE-CADHERIN, and CD34 are endothelial markers. (B) Knockdown of ARHGEF15 mRNA inhibits tube formation in HUVECs. A control siRNA oligonucleotide did not affect VEGF-dependent tube formation of HUVECs; however, siRNA for ARHGEF15 reduced the ability to form a vascular network. (C) Quantification of relative tube length, branch points, and vessel area in control and knockdown HUVECs. Images (B) were captured with a Keyence BioRevo microscope (Plan Fluor 10×/0.30 NA lens) and with BZ-II Viewer.

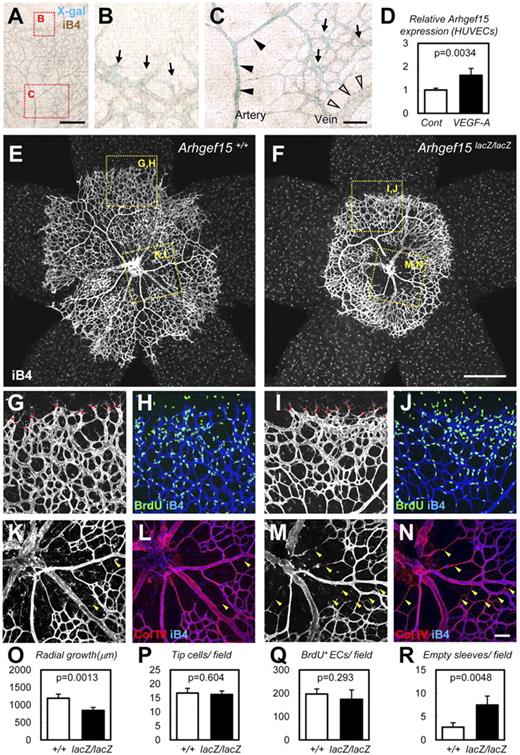

Characterization of Arhgef15 KO and RhoJ KO mice

To further examine the developmental roles of these genes, we created Arhgef15 KO mice as described in “Methods.” A lacZ expression sequence in the first exon was used as a surrogate for endogenous Arhgef15 expression (supplemental Figure 6). We found that lacZ was expressed in arterial and venous ECs of Arhgef15+/lacZ embryos during development (E8.5-E10.5). The number of liveborn Arhgef15 KO mice conformed to a Mendelian ratio (WT, n = 32; Het, n = 70; KO, n = 26), and the mice were subsequently found to be fertile. We investigated the function of Arhgef15 in postnatal vascular development by screening retinal vascularization in neonates, a process that mainly involves sprouting vascular growth. Arhgef15 expression was examined by X-gal staining in Arhgef15+/lacZ embryos at postnatal day 5 (P5) and was found to occur predominantly in arterial ECs, with weaker expression levels in venous and capillary ECs, including tip/stalk cells (Figure 6A-C).42 Because this expression pattern is similar to those of VEGF-induced genes such as Dll4 and ephrin B2,43 we examined the effect of VEGF-A supplementation on ARHGEF15 expression in HUVECs. We found significant up-regulation of ARHGEF15 in the presence of VEGF-A (Figure 6D). However, neither Notch inhibition (γ-secretase inhibitors) nor Notch gain-of-function (Jag1-peptides)44 significantly altered Arhgef15 expression (data not shown), suggesting that Arhgef15 lies downstream of VEGF signaling and is distinct from the Notch/ephrin B2 pathway.44 Next, we examined the retinal vasculature of Arhgef15 KO mice. Arhgef15 KO mice showed delayed radial growth and sparse vasculature in the central area of their retinas compared with WT mice (Figure 6E-F,O). At the vascular front, the numbers of tip cells/filopodia were not significantly different between WT and Arhgef15 KO mice, and the same was true for endothelial proliferation (Figure 6G-J,P-Q; supplemental Figure 7). We identified a potential mechanism for the vascular sparsity in the central retina of Arhgef15 KO mice, which showed a marked increase in empty basement membrane sleeves that were positive for collagen IV but lacked endothelial markers, such as isolectin-B4 (Figure 6K-N,R), indicating increased vessel regression.45 Overall, our observations suggest that Arhgef15 deficiency primarily impairs stabilization of vessels rather than interfering with sprouting or proliferation at the vascular front. Similar phenotypes have been reported in astrocyte-specific VEGF knockouts,46 suggesting a critical role for Arhgef15 as a downstream effector of astrocyte-derived VEGF. Consistent with this notion, Arhgef15 is induced by VEGF. It has been reported that ECs undergo dynamic shuffling, such as backward and forward movements, and overtaking each other, even at the tip.16,47 Therefore, it is conceivable that defects in the central retina, even in the absence of defects in the vascular front, lead to the inhibition of overall vascular growth. Some genes control both physiologic angiogenesis, such as in embryonic development, and pathologic angiogenesis, such as in tumor growth. To address the effect of deficiency of Arhgef15 on tumor growth, we implanted LLC cells into the back of Arhgef15 KO mice and their WT littermates and found no significant difference in subsequent tumor weights between the 2 genotypes. It is known that tumor angiogenesis depends on the tumor cell type. Thus, further study will be needed to elucidate unambiguously the functional role of Arhgef15 in tumor angiogenesis.

Arhgef15 stabilizes vessels in neonatal retinal vasculature. (A-C) X-gal staining combined with isolectin B4 (iB4) staining of Arhgef15+/lacZ retinas at P5. Arhgef15 is predominantly expressed in arterial ECs (closed arrowheads), whereas weaker expression was detected in venous (open arrowheads) and capillary ECs, including tip/stalk cells (arrows). (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 50 ng/mL VEGF-A (12 hours) after 12 hours of serum starvation (n = 4). (E-N) Whole-mount IHC of P5 retinas with the indicated Abs. Arhgef15 KO mice showed delayed radial growth and sparse vasculature in the central retina (E-F). Although the number of tip cells (red points in G and I) and proliferation (H,J) were not affected, Arhgef15 KO mice showed markedly increased empty sleeves (Col IV(+) iB4(−); arrowheads in K-N). (O-R) Quantification of each parameter (n = 4). Scale bars: 500 μm (E-F), 200 μm (A), and 50 μm (B-C,G-N).

Arhgef15 stabilizes vessels in neonatal retinal vasculature. (A-C) X-gal staining combined with isolectin B4 (iB4) staining of Arhgef15+/lacZ retinas at P5. Arhgef15 is predominantly expressed in arterial ECs (closed arrowheads), whereas weaker expression was detected in venous (open arrowheads) and capillary ECs, including tip/stalk cells (arrows). (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 50 ng/mL VEGF-A (12 hours) after 12 hours of serum starvation (n = 4). (E-N) Whole-mount IHC of P5 retinas with the indicated Abs. Arhgef15 KO mice showed delayed radial growth and sparse vasculature in the central retina (E-F). Although the number of tip cells (red points in G and I) and proliferation (H,J) were not affected, Arhgef15 KO mice showed markedly increased empty sleeves (Col IV(+) iB4(−); arrowheads in K-N). (O-R) Quantification of each parameter (n = 4). Scale bars: 500 μm (E-F), 200 μm (A), and 50 μm (B-C,G-N).

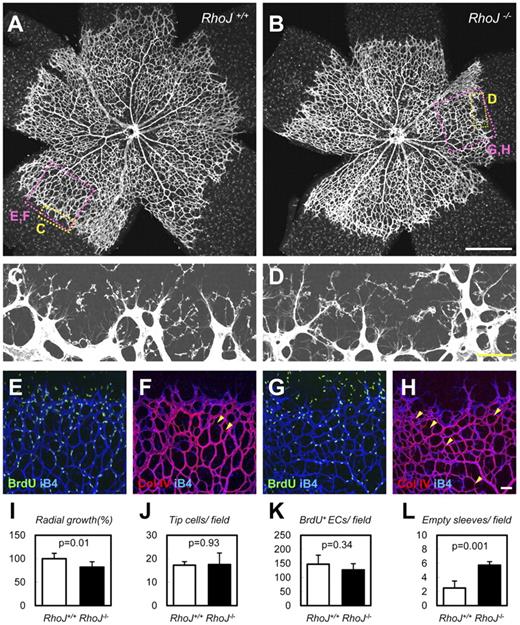

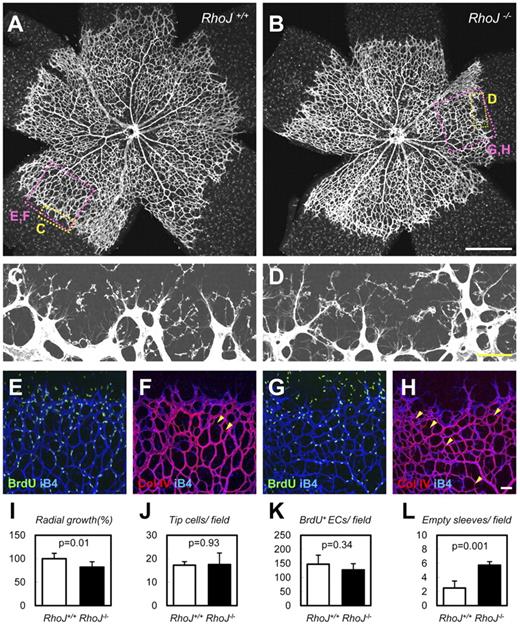

We also created RhoJ KO mice as described in “Methods,” because knockdown of RHOJ severely impaired tube formation in HUVECs. It is reported that RhoJ is an endothelial Rho that plays a critical function in lumen formation. Liveborn RhoJ KO mice were obtained in a Mendelian ratio (WT, n = 18; Het, n = 53; KO, n = 23) and were subsequently found to be fertile. We investigated the function of RhoJ in retinal vascularization in neonates. RhoJ KO mice showed slightly but significantly delayed radial growth in the area of their retinal vasculature compared with WT mice (Figure 7A-B,I). At the vascular front, the numbers of tip cells/filopodia were not significantly different between WT and RhoJ KO mice, and the same was true for endothelial proliferation (Figure 7C-E,G,J-K). RhoJ KO mice showed marked increase in empty sleeves (Figure 7F,H,L), which may explain their delayed radial growth. Different from Arhgef15 KO mice, increased vessel regression was evident in the vascular front but not central retina. In stark contrast to Arhgef15, RhoJ is expressed in capillaries in the vascular front but not in arteries,48 which probably causes the spatial difference in manifestations of abnormalities between Arhgef15 and RhoJ KO mice.

RhoJ stabilizes vessels in neonatal retinal vasculature. (A-H) Whole-mount IHC of P5 retinas with the indicated Abs. RhoJ KO mice showed delayed radial growth and increased empty sleeves (Col IV(+) iB4(−); arrowheads in F,H). (I-L) Quantification of each parameter (n = 4). Scale bars: 500 μm (A-B) and 50 μm (C-H).

RhoJ stabilizes vessels in neonatal retinal vasculature. (A-H) Whole-mount IHC of P5 retinas with the indicated Abs. RhoJ KO mice showed delayed radial growth and increased empty sleeves (Col IV(+) iB4(−); arrowheads in F,H). (I-L) Quantification of each parameter (n = 4). Scale bars: 500 μm (A-B) and 50 μm (C-H).

Discussion

We exploited Flk1 KO fetuses, which lack vascular ECs, to perform a genome-wide survey to identify EC-enriched genes. Our gene ontology analysis indicated that the identified genes were involved in vascular formation such as “angiogenesis,” “blood vessel development,” “vasculature development,” and “blood vessel morphogenesis” (supplemental Table 4; data not shown). This suggests that our screening strategy was effective at identifying genes that are highly expressed in ECs. Indeed, Arhgef15, Arap3, Gpr116, Gpr182, and Tmem204 were specifically expressed in the vascular ECs of fetuses at 8.5-10.5 dpc. Knockdown experiments indicated that 6 of 22 tested genes had a role in tubular network formation in HUVECs. Furthermore, deficiency of Arhgef15 and RhoJ in the retina affected retinal vascularization, showing that our screening strategy identified genes with roles in angiogenesis.

Ten transcription factors were present among the genes obtained here, namely, Tal1, Lyl1, Gata2, Runx1, Sox (Sox7, Sox17, and Sox18), and Ets (Fli1, Etv2, and Erg). Four of these, Tal1, Fli1, Sox2, and Etv2, were shown to have roles in vascular development. It will be interesting to investigate whether other genes are associated with vascular anomalies. It is notable that Tal1, Lyl1, Runx1, and Fli1 are causative genes for leukemia. Gene ontology analysis indicated that 14 other genes identified here belong to the “nucleus” category (Figure 2E; supplemental Table 4), suggesting that they might be involved in vascular development, gene transcription in endothelium, or leukemia.

The genes identified in this study were expressed in newly formed ECs. At the developmental stage at which ECs begin to appear, the primitive vascular plexus is undergoing a complex remodeling process in which growth, migration, sprouting, and pruning lead to the development of a functional circulatory system. One might imagine that this aggressive angiogenic development occurs with the use of similar molecular mechanisms as tumor angiogenesis. Mirp2 (Kcne3) and Cd109, which are expressed in tumor endothelium but not in normal endothelium,27,28 were obtained in our microarray screen. Although previous studies found that tumor and normal endothelium in the adult differ at the molecular level, our study indicates that some genes are shared by embryonic angiogenesis and tumor angiogenesis.

Overall, we identified 184 genes that are highly expressed in the ECs of embryos at 8.5 dpc by microarray analysis. Most of these genes, if not all, have not been characterized as EC enriched in previous studies. The endothelium is implicated in various physiologic processes, such as angiogenesis, blood pressure control, a niche for stem cells, and inflammation.49 Thus, the transcriptome identified by this study may provide us not only with an improved understanding of the background of vascular development but also with candidate genes for blood pressure control, a niche for stem cells, and inflammation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Y. Suzuki and M. Ojima for technical assistance. H.T. thanks Mr T. Azami for help with the confocal microscopy analysis.

This work was supported in part by Genome Network Project (S.T.), Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology (M.E.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C, 23500488, M.E.), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Innovative Areas “Cellular and Molecular Basis for Neuro-vascular Wiring” (No. 23122503, M.E.) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

Authorship

Contribution: M.E. designed the research. H.T., R.Y., R.S., and K.M. performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis on mouse cells and HUVECs; R.S., T.K., and K.U. performed the microarray analysis; Y.K. examined whole-mount retina; R.Y., R.S., H.M., H.I., S. Takano, S. Takahoshi, and A.O. performed the in situ hybridization analysis; H.I. performed the whole-mount IHC; and M.E. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Masatsugu Ema, Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba 305-8575, Japan; e-mail: masaema@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

H.T., K.M., and R.Y. contributed equally to this study.