In this issue of Blood, Janelsins et al1 report that substance P (SP)–treated dendritic cells (DCs) efficiently home to lymph nodes, where they induce inflammatory DCs to produce interleukin-12 (IL-12), thereby promoting type 1 polarized immunity.

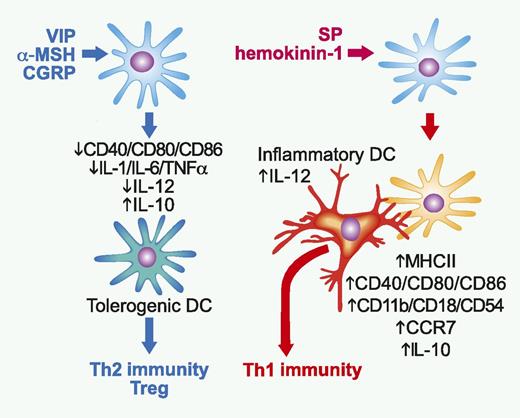

Opposing impacts of anti-inflammatory vs proinflammatory neuropeptides on DCs. VIP, α-MSH, and CGRP downregulate expression of costimulatory molecules and production of inflammatory cytokines and IL-12 by DCs, whereas augmenting their production of IL-10. The resulting tolerogenic DCs, in turn, induce immunologic tolerance by favoring Th2-biased immunity and promoting Treg generation. By contrast, SP and hemokinin-1 elevate expression of MHC class II molecule, costimulatory molecules, adhesion molecules, and CCR7 on DCs. Not only do the DCs stimulated with NK1R agonists migrate to draining lymph nodes (LNs), but they also induce recruitment of Ly6C+ inflammatory DCs to the same LNs, where they physically interact with and trigger IL-12 production by inflammatory DCs. Thus, NKR1 agonists promote Th1-polarized immunity through indirectly activating inflammatory DCs. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Opposing impacts of anti-inflammatory vs proinflammatory neuropeptides on DCs. VIP, α-MSH, and CGRP downregulate expression of costimulatory molecules and production of inflammatory cytokines and IL-12 by DCs, whereas augmenting their production of IL-10. The resulting tolerogenic DCs, in turn, induce immunologic tolerance by favoring Th2-biased immunity and promoting Treg generation. By contrast, SP and hemokinin-1 elevate expression of MHC class II molecule, costimulatory molecules, adhesion molecules, and CCR7 on DCs. Not only do the DCs stimulated with NK1R agonists migrate to draining lymph nodes (LNs), but they also induce recruitment of Ly6C+ inflammatory DCs to the same LNs, where they physically interact with and trigger IL-12 production by inflammatory DCs. Thus, NKR1 agonists promote Th1-polarized immunity through indirectly activating inflammatory DCs. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Nerve fibers project to virtually all organs of the body not only to monitor the external environment, but also to control the internal homeostasis. Neutropeptides released from nerve fibers (and inflammatory leukocytes) facilitate the immune system to accomplish its 2 opposing tasks of maintaining immune tolerance to self-antigens, while inducing robust immune responses against external insults. A wide variety of neutropeptides have been shown to suppress host inflammatory and immune responses. These anti-inflammatory neutropeptides include vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone (α-MSH), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), adrenomedullin, urocortin, and cortistatin.2 VIP and α-MSH are both known to inhibit phagocytic activities of innate leukocytes, such as neutrophils and macrophages. Moreover, VIP and α-MSH maintain T helper 2 (Th2)–biased immune balance by acting directly on differentiating T cells, as well as on DCs (see figure). VIP, α-MSH, and CGRP have been shown to downregulate surface expression of costimulatory molecules and production of inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α [TNFα]) and IL-12 by DCs, while augmenting their production of IL-10.2-4 The resulting “tolerogenic” DCs, in turn, induce immunologic tolerance by favoring Th2-biased immunity and promoting the generation of regulatory T cells.2,3

In marked contrast to the anti-inflammatory neuropeptides, a limited number of neuropeptides have been shown to promote inflammatory responses and Th1-directed immunity. SP is an undecapeptide with the amino acid sequence of Arg-Pro-Lys-Pro-Gln- Gln-Phe-Phe-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2 originally identified in extracts of brain and intestine as a hypotensive and spasmogenic factor. In the central nerve system, SP is involved in complex brain functions associated with pain, depression, anxiety, and stress responses. SP and hemokinin-1, both of which belong to the tachykinin family of neuropeptide, primarily bind to G-protein–coupled, neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R) expressed on a wide variety of cell types. SP augments inflammation by causing local vasodilatation and by attracting and activating neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, monocytes, and macrophages.5 DCs are known to express NK1R regardless of their maturation status, and SP has been reported to sustain the survival of DCs in culture and in living animals.6 On the other hand, immunologic impacts of NK1R agonists on DCs remain relatively unknown. Using natural SP, homokinin-1, and a synthetic NK1R-specific SP homolog, Janelsins et al1 sought to fill in this gap. These investigators found that NK1R agonists increase surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecule, costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86), adhesion molecules (CD11b, CD18, and CD54), and C-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7) in murine bone marrow–derived DCs. Although NK1R agonists failed to alter the secretion of IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-12 by DCs, they potently inhibited IL-10 production. When injected subcutaneously after antigen loading, those DCs stimulated with NK1R agonists migrated efficiently to skin-draining LNs and elicited robust activation of CD4 and CD8 T cells producing interferon-γ and antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells. How can those DCs that secrete only negligible amounts of IL-12 initiate type 1 immunity? The DCs pretreated with NK1R agonists were found to induce marked recruitment of Ly6C+ inflammatory DCs to the skin-draining LNs, where they physically interacted with inflammatory DCs and promoted their production of IL-12. Janelsins et al1 elegantly determined the source of IL-12 by transferring SP-pretreated DCs from IL-12 p35-deficient mice into wild-type recipient mice—these recipient mice still exhibited robust Th1-polarized immunity. Their findings demonstrate that NK1R agonists counteract with anti-inflammatory neuropeptides by directing DC functionality into contrary directions (see figure).

At the same time, the above findings raise several important questions. What are the underlying mechanisms by which anti-inflammatory neutropeptides and proinflammatory neuropeptides produce opposing outcomes in DCs? VIP, α-MSH, and CGRP are known to downregulate the transcription of inflammatory cytokine genes by activating the cyclic AMP (cAMP)–protein kinase A pathway, thereby inhibiting the nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) pathway.2

Interestingly, Janelsins et al1 showed that NK1R agonists triggered NFκB-dependent gene transactivation in DCs. This may corroborate a previous report showing that VIP and CGRP, but not SP, elevated intracellular cAMP levels in DC preparations isolated from skin.7

Do NK1R agonists polarize T-cell differentiation only into the type 1phenotype? Recently, SP and hemokinin-1 have been reported to switch noncommitted human memory CD4 T cells into Th17 cells producing large amounts of IL-17A and interferon-γ.8 Thus, it will be interesting to determine whether SP-treated DCs can also promote Th17-polarized immune responses. What is the clinical significance? Increased levels of SP and elevated NK1R expression have been detected in lesions of inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, suggesting pathogenic roles for SP in autoimmune inflammatory disorders.5 It is, therefore, tempting to speculate that tissue-resident DCs may undergo Th1-biased maturation in the SP-rich microenvironment at the inflammatory lesions. If so, currently available peptide and nonpeptide NK1R antagonists9 may be used to redirect DC maturation in those autoimmune diseases. Alternatively, NK1R agonists may serve as unique DC-targeted adjuvants specifically designed to harness Th1-polarized immunity against cancer cells and intracellular pathogens. In fact, this concept has been proven by local administration of a synthetic NK1R-specific SP homolog into the vaccination sites.10 Obviously, many questions remain to be addressed. Nevertheless, the study by Janelsins et al provides key information for our understanding of immunologic impacts of NK1R antagonists.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.