Abstract

The B7 family consists of structurally related, cell-surface proteins that regulate immune responses by delivering costimulatory or coinhibitory signals through their ligands. Eight family members have been identified to date including CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2), CD274 (programmed cell death-1 ligand [PD-L1]), CD273 (programmed cell death-2 ligand [PD-L2]), CD275 (inducible costimulator ligand [ICOS-L]), CD276 (B7-H3), B7-H4, and B7-H6. B7 ligands are expressed on both lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues. The importance of the B7 family in regulating immune responses is clear from their demonstrated role in the development of immunodeficiency and autoimmune diseases. Manipulation of the signals delivered by B7 ligands shows great potential in the treatment of cancers including leukemias and lymphomas and in regulating allogeneic T-cell responses after stem cell transplantation.

Introduction

Cancer and the immune system are fundamentally interrelated.1,2 Cancer cells express tumor-specific aberrant antigens3,4 and must therefore evade immune detection to survive,5 either by inducing immunosuppression2 or deriving survival signals from tumor-infiltrating immune cells.6 T cell–mediated antitumor immunity4 requires recognition of cancer-associated antigen by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), and appropriate costimulatory and repressive secondary signals arising from complex interactions with other immune, stromal, and tumor cells. Dysfunction of costimulation pathways may contribute to failed antitumor immunity.

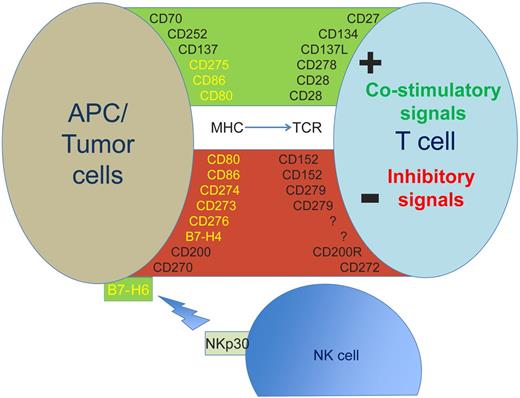

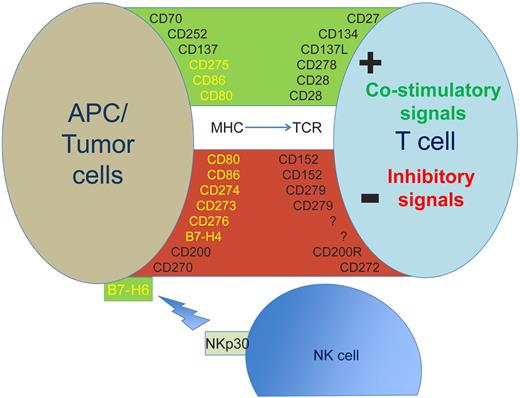

The B7 system (Table 1) is one of the most important secondary signaling mechanisms and is essential in maintaining the delicate balance between immune potency and suppression of autoimmunity. Potential therapeutic applications include immune-boosting adjuvants to conventional anticancer therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), antitumor vaccines, bioengineered T cells as well as attenuation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The B7 family is only one aspect of a complex signaling network (Figures 1 and 2) that comprises other immunoglobulin superfamily (IGSF) members, the tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFRSF), chemokines, cytokines, and adhesion molecules. However, based on a substantial evidence base and a growing therapeutic armory, the B7 family requires particular attention, as summarized in Table 2.7

Expression of selected antigens expressed on the cell surface of PC or tumor cells and their costimulatory or inhibitory ligands on the surface of T cells or NK cells. B7 family members are shown in yellow. APC indicates antigen presenting cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NK, natural killer cell; and TCR, T-cell receptor.

Expression of selected antigens expressed on the cell surface of PC or tumor cells and their costimulatory or inhibitory ligands on the surface of T cells or NK cells. B7 family members are shown in yellow. APC indicates antigen presenting cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NK, natural killer cell; and TCR, T-cell receptor.

The standardized approach to nomenclature is the cluster of differentiation (CD), which has not yet been applied to all members of the family. While many researchers are more familiar with their original names, which are still widely used in the literature, for the purposes of this review, the CD designation is used wherever possible.

B7 founder members

CD80, CD28, and CD152 (CTLA-4)

The first B7 family member was a molecule discovered on activated, proliferative splenic B lymphocytes,7 and termed B7 in an early nomenclature convention attributed to B cell–defining markers. Subsequent cloning and sequencing of the B7 gene revealed sequence homology with IGSF members and expression in a variety of lymphoid malignancies.8 B7 was found to bind CD28,9 an IGSF member on T cells, which augmented their activation.10-12 Further molecular profiling identified a CD28 homologue, CD152 (cytolytic T cell–associated sequence-4 [CTLA-4]),13 which mapped to the same chromosomal region as CD2814 and bound B7 more potently.15 The B7 signal blockade using a CTLA-4.Ig construct led to suppression of humoral16 and cell-mediated immune responses,17 while transfection of immunogenic murine melanoma cell lines with B7 enhanced antitumor immunity, which could be abrogated by CTLA-4.Ig.18

Initial experiments suggested that both anti-CD28 and anti–CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were T-cell activators,19 but contrary evidence showing a suppressive role for CTLA-4 soon emerged20,21 and was conclusively demonstrated in Ctla-4−/− mice, which rapidly develop fatal lymphoproliferation and multisystemic autoimmunity.22,23 Multiple mechanisms for CTLA-4–mediated immunosuppression are proposed (Figure 3), including competition for CD28 binding and induction of suppressive intracellular signaling pathways (reviewed in Rudd and Schneider24 ).

Differential cellular binding of 2 B7-directed mAbs (anti–BB-1 and anti-B7) suggested distinct molecular targets (B7-1/CD80 and B7-2/CD86),25,26 a finding confirmed when the B7-2 gene was cloned from a CTLA-4.Ig-binding activated-B-cell cDNA library.27 Both molecules were demonstrated on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) including dendritic cells (DCs) and activated macrophages.28

CD80/CD86 expression in malignancy

A role for B7 in antitumor immunity was confirmed by the demonstration that cytotoxic T cells better eradicated murine malignancies transfected to express B7-1 and B7-2.18 In contrast to solid tumors, both molecules are expressed innately in many hematologic malignancies.29-31 After in vitro activation, follicular lymphoma (FL) cells up-regulate CD80/CD86 and other costimulatory and adhesion molecules,32 thereby increasing APC activity and augmenting primed T-cell responses. The malignant Hodgkin Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells of classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) express high levels of CD80/CD86.33,34 Expression in multiple myeloma (MM) is variable, and may influence prognosis.35 Expression is low in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) unless the cells are stimulated,36 and rare in acute leukemia.37,38 However, expression of these costimulatory molecules alone is clearly inadequate for effective antitumor immunity because even malignancies showing high expression levels inevitably progress without therapy. Both molecules are widely expressed in the tumor immune microenvironment, and loss of expression may contribute to the failed antitumor responses.30,39,40

Therapeutic modulation of CD28, CD152, and CD80/86

CD80 has been targeted using the mAb galiximab41 in phase 1 and 2 trials in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and CHL, both alone42 and combined with rituximab.43,44 Off-target immune suppression through CD80 blockade may limit the efficacy of such an approach. Anti-CD28 mAb therapy showed preclinical promise as an agent that could specifically expand regulatory T-cell subsets as therapy for autoimmune disorders. However, the subsequent clinical trial led to disastrous toxicity resulting from the use of too high a dose of the antibody and an unanticipated massive cytokine storm,45 urging caution in future therapeutic approaches to B7 pathway modulation. The first B7 pathway-targeting agent, anti–CTLA-4 mAb (ipilimumab) has now been Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.46,47 Evidence is accumulating for its efficacy in hematologic malignancies, including in vitro enhancement of antitumor T-cell responses.48 Efficacy as a single agent is limited, although use in combination therapies may improve this.

Expansion of the B7 family and an immunosuppressive axis: CD274 (B7-H1/PD-L1), CD273 (B7-DC /PD-L2), and CD279 (PD-1)

A GenBank database B7 homology search identified a gene (B7-H1/CD274) encoding a protein distinct in amino acid sequence and tissue distribution from the founder B7 members, but with a similar tertiary protein structure.49 Expression in hematologic tissue was restricted to activated T cells and monocytes, although nonhematologic expression was widespread. Its natural ligand was neither CD28 nor CTLA-4 and proved elusive. In contrast to the effects of CD80/CD86.Ig, B7-H1.Ig enhanced proliferation in activated T cells, but induced IL10 and IFN-γ production with negligible IL4 and IL2.

A subtractive cDNA library comparing DCs and macrophages revealed another homologous protein (B7-DC) whose structure and genomic sequence was similar to B7-H1, and which failed to bind CD28 or CTLA-4.Ig.50 B7-DC.Ig stimulated activated T cells more potently than CD80.Ig, inducing IFN-γ and IL2 production and, in contrast to B7-H1, very little IL10. Its ligand, programmed cell death 1 [PD-1], a molecule discovered a decade before, also bound B7-H1. The properties of this new receptor/ligand interaction were not stimulatory like CD28, but profoundly inhibitory.

An experiment designed to reveal mechanisms of programmed cell death, applied subtractive hybridization cDNA library cloning to T-cell lines and identified a cell death–specific gene.51 CD279 (PD-1) was an IGSF homologue and, consistent with a role in T-cell turnover, found predominantly in the thymus. Expression was confirmed in activated circulating human T and B cells.52,53 Pd-1−/− mice developed splenomegaly and a systemic autoimmune syndrome suggesting a role in immunosuppression.54

Structural similarities between CD279 and CD152 (CTLA-4), but without CD80/86 binding,55 suggested an interaction between the B7-stimulatory and PD-1–inhibitory systems. A PD-1–specific ligand, coexpressed with CD80/CD86 on APCs and other nonhematopoietic tissues, was discovered through further B7-homologue searches and cloned from human and murine cDNA libraries.56 Termed CD274 (PD-1-ligand-1 [PD-L1]), ligation with PD-1 induced profound suppression of T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion, which was overcome by excess anti-CD28 or anti-CD3. PD-L1 and B7-H1 transpired to be the same molecule, while B7-DC,50 independently named PD-L2 (CD273) after an expressed sequence tag (EST) database search for PD-L1 homologues,57 identified the second ligand for CD279.

Although initial in vitro work showed PD-L1/PD-L2.Ig transmitted stimulatory signals to activated lymphocytes,49,50 binding to their ligand PD-1 conveyed potent suppressive signals.56,57 Evidence for bidirectional signaling emerged from murine B cell– and T cell–specific gene deletion and transplantation experiments.58 Knock-out of T cell–specific PD-1 or B cell–specific PD-L2 impaired long-lived plasma cell formation, implying a stimulatory role for reverse signaling. Receptor/ligand pairing is also more promiscuous than originally believed. A search for binding partners for CD80 using Ctla-4−/−Cd28−/− activated CD4+ T cells suggested PD-1 as a candidate, with CD80 signaling through PD-1 independent of CTLA-4 or CD28, to inhibit T-cell proliferation.59 The complexity of the B7 system is becoming clear: context and direction of signaling determines responder cell outcome.

CD279 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), and CD273 (PD-L2) expression in malignancy

The PD-1/PD-L1/PD-L2 axis has been widely demonstrated to contribute to failed antitumor immunity. Pd-1−/− mice and Pd-1wt/wt mice treated with anti–PD-L1 antibody demonstrate superior rejection of PD-L1–expressing tumors60 through PD-1–dependent and –independent pathways.61 Growth of pancreatic cancer cells in immunocompetent B6 mice is impaired by administration of anti–PD-1 or PD-L1 mAbs.62 Tumor-specific T cells fail to lyse melanoma cells in host 2C/Rag2−/− mice despite stimulatory IFN-γ treatment because IFN-γ also induces up-regulation of immunosuppressive PD-L1.63 PD-L1 is expressed in many tumors and cell lines57,61 and appears to be associated with poorer outcome in solid malignancy,62,64-67 while PD-1 expression by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) may also confer poorer outcomes.68 After treatment using a tumor-vaccination strategy of murine acute leukemia, long-lived residual leukemia cells were found to up-regulate PD-L1, suggesting a mechanism of leukemia persistence and relapse.69 These cells resisted CTL-mediated cell lysis, which could be overcome by anti–PD-L1 mAbs. However, blockade using anti–PD-1 mAbs did not reverse CTL resistance, while blocking CD80 had a similar effect to a PD-L1 block. The B7 systemÆs complexity is further illustrated by these findings: CD274 appears to have further immunosuppressive binding partners, while CD80 may be capable of mediating suppressive as well as costimulatory signals.70

There is sparse and conflicting evidence for CD274 (PD-L2) expression in acute leukemia,71,72 although the molecule is apparently up-regulated on malignant cell exposure to IFN-γ or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand, and at relapse. Evidence for reduced T cell–mediated specific lysis in vitro correlates with CD274 expression and is reversible by blocking CD274.73 Functional work in CLL has demonstrated a clear role for the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in mediating systemic, as well as antitumor, immune defects.74 Expression of CD279 by circulating T cells and CD274 by leukemia and FL cells is greater than in nonmalignant control cells, while CD274 expression is associated with poorer clinical outcome. T cells derived from patients with various malignancies have impaired in vitro ρ-GTPase signaling with reduced immune synapse formation.74 This defect is reversed by treatment with anti-PD1 and anti–PD-L1 mAbs, along with blockade of further inhibitory molecules CD200, CD270, and CD276 (B7-H3). Lenalidomide exposure also reverses this defect, coincident with down-regulation of CD274 and CD276 expression.74 These findings, along with evidence that CD80 expression is up-regulated on lenalidomide-exposed CLL cells,75 provide some insight into the drugÆs mechanism of action. In patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), CD279 expression on CD8+ T cells is up-regulated compared with ATLL-free HTLV1+ (human T-cell lymphotrophic virus) controls.76

CD279 is invariably expressed in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, frequently in CLL, but absent in most other NHL.77-79 CD279 is expressed in the immune microenvironment of NHL, where it may have a prognostic significance,80 and there are conflicting reports of expression in the CHL microenvironment.81-83 Evidence for expression of CD274 in NHL is sparse and inconsistent. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometric studies have shown expression by the malignant cell in the majority of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL)84 and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), a minority of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and not at all in most other NHL.85 CD274 is overexpressed in the HRS of CHL82,86 associated with copy number aberrations86,87 and activating translocations involving the 9p24 chromosomal region containing the CD273 and CD274 genes,88 and upstream through the CD274 and CD273 expression-regulating JAK2 pathway.86 Limited in vitro evidence suggests that there is CD274-dependent suppression of T cells in CHL, evidenced by suppressed proliferation and IFN-γ production.82,85

There is variable expression of CD274 in myeloma89,90 with evidence for an important role in myeloma-induced immunosuppression. CTL generated in vitro by exposure to IFN-γ–treated myeloma cell lines show impaired cytolysis of subsequently presented target myeloma cells.89 NK-cell trafficking and cytotoxic potency in vitro is augmented by pretreatment with anti–PD-1 mAb.91 An autologous transplantation and costimulator/vaccine-based treatment strategy for myeloma in a cell line–based mouse model, which had showed evidence for the emergence of dysfunctional circulating CD279-expressing CD8+ T cells, is augmented by the administration of PD-L1 antibodies.90

While somewhat conflicting and lacking functional corroboration, these findings suggest that therapeutic modulation of this axis in hematologic malignancy may have a role.

Therapeutic modulation of CD274, CD279, and CD273

Fully humanized IgG4 mAbs targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis have reached clinical trials. Anti PD-L1 therapy (BMS936559) was administered to 160 heavily pretreated patients with a diverse group of solid tumors in a phase 1 trial.92 Objective and often durable responses were observed in up to 19% of patients, along with autoimmune and infusion reactions consistent with the murine PD-L1−/− models. A similar clinical trial of an anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy (BMS936558) demonstrated comparable response rates in 296 patients.93 There was an association between response and level of tumor PD-L1 expression. Further combination therapy approaches using anti–PD-1 mAbs are under way, including combination with the anti–CTLA-4 mAb ipilimumab in melanoma (NCT01024231), with conventional combination chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NCT01454102) and with tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib and pazopanib in renal cell carcinoma (NCT01592370). Another PD-1 antibody (MK-3475) has also shown activity in patient with advanced solid tumors.94 A phase 1 safety and pharmacokinetic study of the anti–PD-1 mAb in advanced diverse hematologic malignancies showed a reasonable safety profile and a 33% overall response rate95 with further monotherapy and combination therapy trials proposed. The results are promising, but these drugs remain at an early stage of development and are likely to find their most active role as immune adjuvants to conventional therapy.

B7 pathway modulation to augment immunotherapy

Allogeneic HSCT

Failure of allogeneic HSCT may in part be mediated by suppressive B7 signaling. Anti–CTLA-4 mAb therapy has been applied successfully in phase 2 clinical trials to treat relapsed CHL, myeloma, and leukemias after allogeneic HSCT96 without the anticipated exacerbation of GVHD seen in murine transplantation experiments.97 Use of PD-L1/PD-1 axis blockade to enhance allogeneic T-cell responses has not yet reached clinical trial, although there is promising preclinical data in a murine AML model using TCR-engineered AML antigen-specific allogeneic T cells.98 Late transfer of these cells led to poorer antitumor responses accompanied by PD-1 overexpression. Responses were restored by treatment with anti–PD-L1 mAb. PD-1 blockade, however, accelerated GVHD lethality.99

Tumor vaccination strategies

B7 molecules may play an essential role in cancer vaccination strategies. Mouse model immunization strategies using highly immunogenic cancer cell lines showed early success, particularly with chemokine costimulatory approaches.100 Tumor lysate-pulsed DCs have been incorporated into some vaccination strategies,101 showing modest success in patients with advanced lymphoma.102 Idiotype-specific tumor vaccines have been produced for myeloma103 and NHL,104,105 while immunogenic tumor-specific antigens have been identified in CLL106,107 and acute leukemia.108 However, vaccination has yet to make any real impact on cancer therapy: an informal meta-analysis incorporating almost 1000 patients with a variety of malignancies showed an overall response rate of < 4%.109

Combining vaccination strategies with immunosuppressive B7 pathway blockade may improve these disappointing outcomes. CTLA-4 mAb-enhanced melanoma rejection has been demonstrated in a clinical trial,110 but studies in NHL have been disappointing, with minimal responses achieved in vaccinated patients treated with ipilimumab.48,111 Encouraging in vitro evidence suggests that a similar strategy could be applied to PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade, although this has yet to be incorporated into any clinical trial. One group showed PD-L1/PD-L2 siRNA silencing improved DC-induced leukemia-specific T-cell responses,112 while another demonstrated enhanced T-cell responses after PD-1 antibody treatment in a myeloma/DC fusion vaccination strategy.113

Bioengineered T cells

In contrast to the active immunization strategies outlined in the previous paragraph, an alternative strategy is to expand and reinfuse autologous bioengineered T cells. Autologous TILs extracted from melanoma biopsies, expanded and reinfused into immunosuppressed recipients, have shown some therapeutic success114-116 but failed to translate to other malignancies. Attempts to augment autologous T-cell specificity for tumor antigens led to TCR bioengineering approaches, first against EBV-driven lymphoproliferative tumors117 and subsequently other tumor-specific antigens.118-120 While clinical responses are reported, reactive clones tend to rapidly lose efficacy or die off altogether.121 Subsequent developments used tumor antigen-inoculated transgenic mice whose T cells express human MHC, expanding tumor-specific T-cell clones and hence deriving ôready rearrangedö TCR genes for transfection into patient-derived T cells.122 Newer techniques incorporate novel receptor constructs into autologous T cells using chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). Here, a rearranged, antigen-specific immunoglobulin variable region gene is combined with intracellular domains of the TCR gene, thus bypassing MHC-restricted antigen recognition. CARs have the advantage of being amenable to further augmentation with costimulatory motifs, of which CD28123 and CD80124 have demonstrated efficacy. CARs incorporating costimulatory modifications have reached phase 1 clinical trials in NHL125 using an anti–CD19-CD28-TCRζ chain construct, and CLL, using an anti–CD19-CD137 construct (a TNFRSF member). Promising results have been observed, even in refractory patients.126 Further optimization is needed and B7 family members will play a central role in this.

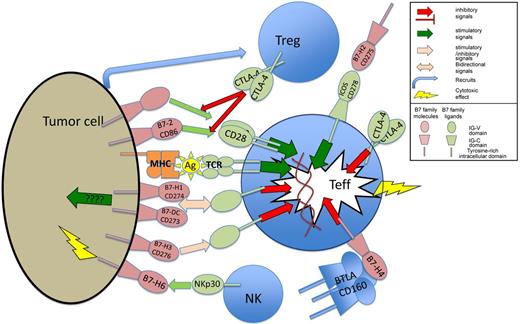

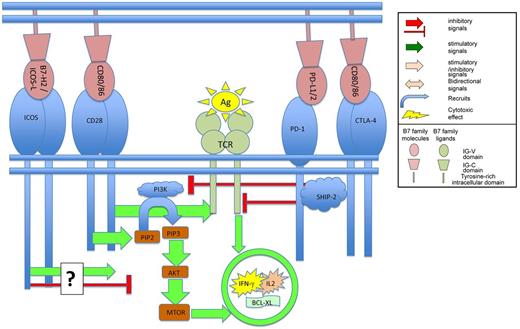

Expression of B7 family members and their receptors have complex interactions with the tumor immune environment. Treg indicates T regulatory cells; Teff, T effector cells; ????, limited evidence base for mechanism; Ag, antigen presented in MHC complex; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; and TCR, T cell–receptor complex.

Expression of B7 family members and their receptors have complex interactions with the tumor immune environment. Treg indicates T regulatory cells; Teff, T effector cells; ????, limited evidence base for mechanism; Ag, antigen presented in MHC complex; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; and TCR, T cell–receptor complex.

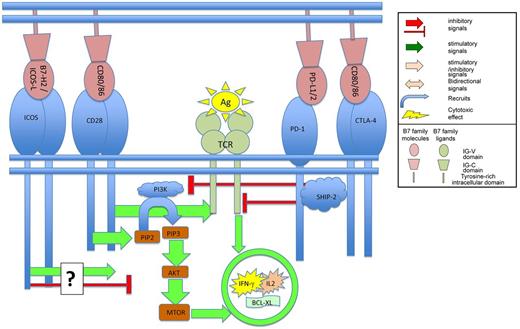

Binding of B7 family members to their ligands on T cells regulates TCR mediated signaling.

Binding of B7 family members to their ligands on T cells regulates TCR mediated signaling.

GVHD attenuation

Allogeneic organ transplantation tolerance may be induced through CD80/CD86 blockade,17 and this finding has encouraged research into a role for the B7 molecules in GVHD. Fully HLA-mismatched mixed lymphocyte reactions are partially abrogated by CTLA-4.Ig or CD80/CD86 antibody treatment, and fully by combination treatment.127 This observation led to a promising clinical trial using CTLA-4.Ig to anergize donor lymphocytes and attenuate GVHD after mismatched allogeneic HSCT for hematologic malignancy.128,129 Early immune reconstitution with relatively low rates of acute and chronic GVHD and viral infection was observed, without the high relapse rates seen after T-cell depletion. Another potential GVHD-attenuating strategy, through PD-1/PD-L1/2 axis manipulation, is a promising hypothetical concept.99

Regulatory T cells

The role of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in suppression of successful antitumor immunity is becoming more evident. There is an association between adverse outcome in solid tumor and increased FOXP3-expressing cells in the microenvironment130 suggesting that their presence suppresses antitumor immunity.131,132 However, in B-cell malignancies the converse has been found, with increased infiltrate associated with improved outcome.133-135 CTLA-4136,137 and PD1/PD-L1138-140 are key pathways used by Tregs to mediate their suppressive activity, hence therapeutic interference with these pathways may contribute by depleting this profoundly suppressive population. These possibilities are under active investigation.

Another costimulatory B7 pathway: ICOS and B7-H2

A further avenue of B7 family costimulatory molecules opened with the discovery of another CD28-like molecule (CD28-related peptide-1 [CRP-1]).141 The human equivalent was confirmed to be a stimulatory molecule expressed only on activated T cells, hence termed inducible costimulator142 (ICOS/CD278). A second clone from the same library, termed B7-related peptide-1 (B7RP-1), had structural similarities to CD80/CD86. ICOS failed to bind CD80/CD86, B7RP-1 failed to bind to CD28 or CTLA-4, but ICOS and B7RP-1 specifically bound each other. B7RP-1 had already been discovered and functionally characterized by an independent group and named ôB7hö143 ; its human homolog was identified and named B7-H2.144 This was the same molecule, ICOS-ligand (B7RP-1/B7h/ICOS-L/CD275), and a later study showed that ICOS-L could bind and costimulate via CD28.145

ICOS may play a role in maintaining durable immune reactions146 and is expressed at particularly high levels in germinal center T cells or TFH (follicular helper) cells.147,148 ICOS-L is constitutively expressed by APCs as well as diverse nonhematologic tissues143 and down-regulated with ongoing inflammation,149,150 in contrast to the activation-induced CD28 ligands CD80/CD86.141,151 In CD28−/− mice, germinal center formation is rescued by ICOS overexpression, while inappropriate overexpression in CD28wt/wt mice induces systemic autoimmunity. T cells derived from ICOS−/− mice show normal thymic T-cell development but dysfunctional proliferation, cytokine and immunoglobulin production, and germinal center formation while paradoxically conferring greater susceptibility to Th1/IFN-γ–mediated disease including experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE).152 The contradictory functions of ICOS suggest a more complex role in T-cell regulation, perhaps favoring IL4/IL10/IL13 and humoral responses at the expense of IFN-γ–mediated cytotoxic/Th1 responses.153 ICOS also plays a role in maintaining immunosuppressive CD4+ T-cell subsets, with ICOS+ enriched CD4+ cell cultures secreting more IL10 and less TNFα than ICOS-depleted systems154 and ICOS, with FOXP3, essential for proper Treg development in the context of autoimmune diabetes and airway immune tolerance in ICOS−/− mice.155

Mutations in the human ICOS gene lead to an attenuated adult-onset common variable immunodeficiency (CVID),156 a predominantly B-cell defect likely arising from a loss of TFH cell function. The disease manifests with a variety of autoimmune phenomena as well as cancer and infection susceptibility.157 The complexity of ICOS makes any therapeutic applications difficult to predict, but its importance is clear.

ICOS and B7-H2 in cancer

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma cells express ICOS, PD-1, and CXCR5, consistent with being the malignant counterpart of TFH lymphocytes.158 ICOS expression has also been described as a potential survival mechanism in NPM-ALK fusion anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells.159 Although induced ICOS-L expression enhances cytotoxic T cell–mediated tumor rejection,160-162 there is sparse and conflicting evidence for its expression in solid tumors,163,164 while expression in myeloma165,166 and acute leukemia is widely heterogeneous.71,166 Despite these sometimes contradictory findings, the ICOS/ICOS-L axis may yet have an indirect role in enhancement of tumor immunity. ICOS is inducible on NK cells, which demonstrate cytotoxicity against ICOS-L–transfected murine leukemia cell lines.167 Cytokine-induced killer cells (CIK) demonstrate MHC-independent cytotoxicity and antitumor activity,168,169 enhanced after ICOS transfection.170 Optimal immunostimulatory therapy using CTLA-4 mAbs may be dependent on an intact ICOS/ICOS-L pathway,171 with CTLA-4 blockade increasing tumor-specific IFN-γ–secreting T cells in cancer patients.172

Therapeutic modulation of ICOS/ICOS-L

ICOS is overexpressed during acute allogeneic solid organ rejection and tolerance is improved with pathway blockade,173 which suggests that this pathway may have importance in GVHD. Murine acute GVHD is reduced if donor Icos−/− mice or ICOS-blocking antibodies are used,174 with less gut and liver GVHD and improved survival175 despite intact Icos−/− donor cell cytotoxic function, cytokine-secretion152,153 and tissue trafficking,175 while Icos−/− recipient mice better tolerate allogeneic HSCT with more rapid and complete donor chimerism.174 However, a further study demonstrated more severe GVHD arising from allogeneic CD8+Icos−/− cell transplantation compared with wild type,176 a contradiction perhaps explained by the differing mouse genetic backgrounds and variable use of Treg-depleting anti-CD25 mAbs. ICOS appears central to GVHD modulation, although because of these controversies, a therapeutic application has yet to emerge.

Controversial immunosuppressive pathways: B7-H3 and B7-H4

CD276 (B7-H3) was identified soon after ICOS,177 not detectable in resting blood cells but present in various normal tissues, in several tumor cell lines and induced on activated DCs and monocytes. B7-H3.Ig stimulates and increases IFN-γ secretion by activated T cells. Its ligand was eventually isolated from a CD28 family database homology search of a murine splenocyte cDNA library. Only TLT-2 showed specific binding,178 a member of the innate immune response-amplifying TREM (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells) molecular family TLT-2 is constitutively expressed on activated CD8+ T cells, inducible on CD4+ T cells and ligation augments T-cell activation. This murine molecule remains controversial in humans, with evidence for179 and against180 its role as CD276 ligand. As such, the function of CD276 also remains contentious, with stimulatory177,181,182 and inhibitory180,183 functions described, and the context of expression clearly central to its role. CD276 expression on solid tumors confers an adverse outcome.184,185 Our group demonstrated expression in CLL,74 down-regulated by lenalidomide, and where antibody-mediated blockade improved in vitro T-cell function.

A further B7/CD28-like molecule expressed on activated T cells, B cells, monocytes, and DCs has been described (B7-H4) which fails to bind CTLA-4.Ig, ICOS.Ig, or PD-1.Ig,186 possesses a binding partner expressed on activated T cells and whose Ig molecular construct, in contrast to that of all other B7-family molecules, inhibits, not stimulates, T-cell function. ‘B7S1’ was discovered by a second group, mAb blockade of which exacerbated murine EAE,187 while a third group identified ‘B7x,’ suggested that it was the same molecule188 and proposed a ligand, a molecule that had been identified during previous gene expression profiling of Th1 polarized cells: BTLA (B and T lymphocyte attenuator). BTLA-binding properties suggested immunosuppressive functions analogous to those mediated by CTLA-4 and PD-1, which was supported by the Btla−/− mouse, which demonstrates enhanced Th1 activity.189 However, subsequent investigations failed to confirm that BTLA is the ligand of B7-H4. A TNFRSF molecule, HVEM, seems to be the major BTLA-interacting immunosuppressive molecule.190

Although B7-H3 and B7-H4 are structurally related B7 family members, there is little consensus on function or binding partners. Crosstalk between other pathways, stimulatory as well as repressive functions, inducible as well as constitutive, tissue-dependent expression and 2-way signaling without clear receptor/ligand polarity are likely complexities existing across all molecules of this class and not only these more recently described members.

B7-H6: a tumor-specific family member

Investigation into natural killer cell (NK) effector mechanisms revealed the most recently identified member of the B7 family, B7-H6, a PD-L1/B7-H3 homologue specifically binding the CTLA-4-homologous NK-effector molecule NKp30.191 Membrane-bound B7-H6 activates NK cells, leading to degranulation and IFN-γ secretion. Unlike other B7 family members, B7-H6 is not expressed in any normal tissue even after activation, but is expressed in a variety of primary tumors and cell lines. The potential for therapeutic manipulation is clear, already inspiring incorporation of NKp30 into CAR constructs.192

An extended B7 definition? Butyrophilin and Skint

Other B7 homologues have been described with potential importance in cancer immune surveillance193,194 and immune modulation, including the diverse Butyrophilin195 family and the epidermal T cell–associated Skint (Selection and upKeep of INTraepithelial T cells) family.196 Butyrophilin subfamily 3 (BTN3) has a structural similarity to B7-H4197 and is expressed on immune cells198 as well as human ovarian cancer,197 while BTN3 agonists may induce immunosuppression.199 However, functional data are conflicting200 ; no ligand has been determined and no in vivo data generated. These molecules are intriguing but their role in cancer immunology remains speculative.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the B7 family has expanded enormously because the costimulatory pathways were first described. Contemporary models of immune regulatory networks reflect this complexity. The promise of immune-mediated enhancement of autologous and allogeneic responses through pharmacologic manipulation of this pathway shows substantial promise. Ongoing studies investigating the role of the most recently described members of the family: B7-H3, B7-H4, B7-H6, Butyrophilin, and Skint will likely reveal further potentially modifiable pathways as therapeutic targets for intervention. Whereas manipulation of the B7 family members and their ligands in suppressing GVHD and augmenting GVL after allogeneic HSCT has shown benefit in murine studies, and promising results in limited phase 2 clinical studies, this remains an area for clinical trial development. The contribution of ICOS/ICOS-L to GVHD appears to be fundamental; however, based on our current understanding of this pathway, the complexities of the interactions make predictions of clinical responses difficult to predict. After decades of study, strategies incorporating B7 family members, such as CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathway-inhibiting molecules and CAR-T cells, have finally demonstrated clear clinical benefit, fulfilling the early promise of the importance of this family in hematologic malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from P01 CA81538 from the National Cancer Institute to the CLL Research Consortium (J.G.G.) and by the Baker Foundation (P.G.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.G. and J.G.G. reviewed the literature and wrote the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.G.G. has received honoraria from Celgene, Roche, Napp, Merck, and Pharmacyclics. J.G.G. receives grant funding from National Institutes of Health and Cancer Research UK and receives an honorarium from the American Society of Hematology as an associate editor of Blood. The remaining author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John G. Gribben, Barts Cancer Institute, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, United Kingdom; e-mail: j.gribben@qmul.ac.uk.