Key Points

Live imaging of endothelial to hematopoietic conversion identifies distinct subpopulations of hESC-derived hemogenic endothelium.

Expression of the Notch ligand DII4 on vascular ECs drives induction of myeloid fate from hESC-derived hematopoietic progenitors.

Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated that hematopoietic cells originate from endothelium in early development; however, the phenotypic progression of progenitor cells during human embryonic hemogenesis is not well described. Here, we define the developmental hierarchy among intermediate populations of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). We genetically modified hESCs to specifically demarcate acquisition of vascular (VE-cadherin) and hematopoietic (CD41a) cell fate and used this dual-reporting transgenic hESC line to observe endothelial to hematopoietic transition by real-time confocal microscopy. Live imaging and clonal analyses revealed a temporal bias in commitment of HPCs that recapitulates discrete waves of lineage differentiation noted during mammalian hemogenesis. Specifically, HPCs isolated at later time points showed reduced capacity to form erythroid/megakaryocytic cells and exhibited a tendency toward myeloid fate that was enabled by expression of the Notch ligand Dll4 on hESC-derived vascular feeder cells. These data provide a framework for defining HPC lineage potential, elucidate a molecular contribu-tion from the vascular niche in promoting hematopoietic lineage progression, and distinguish unique subpopulations of hemogenic endothelium during hESC differentiation.

Introduction

Hematopoietic cells have been shown to arise from specialized endothelial subpopulations with hemogenic potential.1-4 In animal models, the transition from endothelial to hematopoietic identity has been directly observed both in vitro and in vivo using live and explanted embryonic tissues; however, analogous studies using human embryos are handicapped by technical and ethical obstacles. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) provide an in vitro platform for studying the initial cellular and molecular events involved in the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs). But a major impediment to the isolation, expansion, and study of hESC-derived HPCs is that their putative cells of origin, the hemangioblast or hemogenic endothelium,5 exist only ephemerally during hESC differentiation, and the early stages of hematopoietic ontogeny in this context have not been clearly described.

During in vivo development, the progressive emergence of hematopoietic rudiments is observed at various sites within the embryo. Numerous studies have demonstrated the existence of hemogenic endothelium in the large vessels of fetal and extra-embryonic tissues,6-9 and recent work suggests that discrete populations of hemogenic ECs may account for primitive and definitive waves of mouse embryonic hematopoiesis.10 Provided that the developmental hierarchy of in vitro ESC differentiation truly recapitulates embryonic events, hematopoietic derivatives obtained from hESCs may be endowed with variable differentiation potential, depending on which embryonic correlate they represent. Yet without anatomic reference points that typically enable isolation and interrogation of important tissues within the embryo, defining the cellular origins, phenotype, and developmental potential of hESC-derived HPCs is a challenging problem.

A clear demarcation of the ontogeny of hematopoietic cells that arise from hESCs would facilitate the integration of in vivo and in vitro developmental studies and enable efforts to generate therapeutically useful cell types. To these ends, we generated a transgenic hESC line that separately identifies emergent endothelial and hematopoietic cells during differentiation and used it to directly observe the spectrum of phenotypic progression from hemogenic endothelium to multipotent HPCs and their derivatives. Live imaging of hemogenic ECs during endothelial to hematopoietic transition (EHT) and subsequent differentiation identified phenotypic milestones during hemato-endothelial specification and revealed a temporal bias in lineage potential that correlates with discreet waves of hemogenesis noted in mouse and human fetal tissues.

Methods

hESC culture

The experiments delineated in this report were performed using WMC-2 hESCs. Permission for use of this cell line was secured after review by the Cornell-Rockefeller-Sloan Kettering Institute ESCRO committee. hESC culture medium consisted of Advanced DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% Knockout Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), L-Glutamine (Invitrogen), Pen/Strep (Invitrogen), β-Mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), and 4 ng/mL FGF-2 (Invitrogen). hESCs were maintained on Matrigel using hESC medium conditioned by mouse embryonic fibroblasts (GlobalStem).

Fetal liver tissue

The Investigational Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical College approved the use of fetal tissues. Three samples of human fetal liver (age 9, 10, and 13 weeks, from Advanced Bioscience Resources) were incubated in Accutase for 20 minutes, followed by dissociation through a p1000 pipette tip and passage through a cell strainer. Cells were collected and stained using directly conjugated antibodies to human VE-cadherin and CD45. The VE-cadherin+CD45− population was collected by FACS for RNA isolation and cell culture.

Lentiviral transduction

The AdE4ORF1, blue fluorescent protein (BFP), GFP, and Dll4 cDNAs were cloned into the pCCL-PGK lentivirus vector.11 This vector was also modified to replace the PGK promoter with a 1.5-kb fragment of the human VE-cadherin gene promoter driving mOrange fluorescent protein or a 1.0-kb fragment of the human CD41a gene promoter driving GFP. Scrambled and Dll4-specific shRNA constructs were cloned into the pLKO vector. Lentivirus particles were generated in 293T cells by the calcium precipitation method as previously described.12 Supernatants were collected 40 and 64 hours after transfection. Clonal hESC lines containing constitutive and tissue specific transgenes were obtained as previously described.13

Differentiation on E4ORF1+ ECs

HUVECs were isolated and transduced with lentiviral AdE4ORF1 as previously described.14 One day before plating hESCs to begin differentiation, mouse embryonic fibroblast conditioned medium was replaced with hESC culture medium without FGF-2 and supplemented with 2 ng/mL BMP4. The next day, hESCs were plated directly onto an 80% confluent layer of E4ORF1+ EC in hESC culture medium (without FGF-2, plus 2 ng/mL BMP4) and not disturbed for 48 hours. This point of culture was considered as differentiation day 0. Cells were sequentially stimulated with recombinant cytokines in the following order: day 0 to day 7 supplemented with 10 ng/mL BMP4; day 2 to point of harvest supplemented with 10 ng/mL VEGF-A; day 2 to point of harvest supplemented with 5 ng/mL FGF-2; and day 7 to point of harvest supplemented with 10 μM SB-431542.

FACS

Flow cytometric analysis and sorting were performed on a FACSAriaII (BD Biosciences). Antibodies used were specific for (CD14 [M5E2], CD15 [HI98], CD33 [P67.6], CD31 [MEC 13.3], CD34 [8G12], CD43 [1G10], CD45 [2D1], CD71 [L01.1], CD73 [AD2], CD235a [HIR2], BD Biosciences), (CD41a [HIP8], CD42a [GR-P], CD61 [VI-PL2], Dll4 [MHD4-46], SSEA3 [MC-631], eBioscience), (VE-cadherin [123413], R&D Systems), and (VEGFR2 [1C11], Imclone). Data were analyzed using FACS Diva software. Sorting at serial dilutions and single cells was done using the FACSAriaII Automated Cell Deposition Unit.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was prepared from cells using the RNeasy extraction kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed using Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative PCR was performed on a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems). Human-specific primer pairs used were: Brachyury, forward, 5′-cagtggcagtctcaggttaagaagga-3′, reverse, 5′-cgctactgcaggtgtgagcaa-3′; Dll4, forward, 5′-aactgcccttcaatttcacct-3′, reverse, 5′-gctggtttgctcatccaataa-3′; HEY1, forward, 5′-gtgcggacgagaatggaaa-3′, reverse, 5′-ctggccaaaatctgggaaga-3′; Oct3/4, forward, 5′-aacctggagtttgtgccagggttt-3′, reverse, 5′-tgaacttcaccttccctccaacca-3′; VEGFR2, forward, 5′-actttggaagacagaaccaaattatctc-3′, reverse, 5′-tgggcaccattccacca-3′. Cycle conditions were: one cycle at 50°C for 2 minutes, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 1 minute. Threshold cycles were normalized to β-actin.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were stained as previously described.15 Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in PBST, and blocked in 5% donkey serum for 45 minutes. Samples were incubated for 2 hours in blocking solution containing primary antibodies that were directly conjugated to Pacific Blue, Alexa-488, -568, or -647. Antibodies used were Oct3/4 ([9E3.2], Millipore), Brachyury ([605402], R&D Systems), CD31 ([MEC 13.3], BD Biosciences) and VEGFR2 (Imclone, [1C1116 ]). Imaging was performed using a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope using a 10× objective.

Live imaging

Cell cultures that were transduced with combinations of PGK-BFP/GFP/mOrange, VPr-GFP/mOrange, and/or CD41a-GFP reporter transgenes were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a stage mounted incubation chamber (Tokai Hit) and exposed at variable intervals on either Eclipse Ti phase contrast (Nikon) or 710 META confocal (Zeiss) microscope using a 10× objective. Cell tracking was done using frame-by-frame analysis.

Colony assay

Hematopoietic derivatives were isolated by FACS and cultured for 10-14 days in collagen-based medium (Megacult) or methocellulose (Methocult) supplemented with hematopoietic cytokines. After enumeration of colony-forming units, the cellular fraction was isolated from methocellulose by centrifugation and labeled with antibodies for flow cytometric analysis. Single cells were sorted directly into Methocult medium using the FACSAriaII Automated Cell Deposition Unit.

Results

hESCs undergo hemato-endothelial differentiation in coculture with vascular feeder cells

We first set out to develop a serum-free platform for robust differentiation of hESCs. Many studies have used feeder-based cocultures composed of murine OP9 fibroblastic and mesenchymal cells to create an in vitro microenvironment that enhances hemato-endothelial differentiation from hESCs.17,18 Primary ECs transduced with the adenoviral gene fragment E4ORF1 (E4ORF1+ ECs14 ) could serve as an alternative to OP9 cells, as they express pro-angiogenic factors and extracellular matrix components that are involved in specification and maintenance of hemato-endothelial identity19-21 while also maintaining their growth potential in serum-free conditions. To investigate this potential, a vascular specific hESC reporter line, in which GFP or mOrange is expressed under control of a promoter fragment of the human VE-cadherin gene (VPr-GFP/mOrange13,15 ), was deposited on E4ORF1+ ECs and serially activated with BMP4, FGF-2, VEGF-A, and SB431542, a small molecule inhibitor of TGF-β signaling (Figure 1A-B; see “Methods”). Four to 5 days after seeding, hESC derivatives began to migrate onto the feeder layer (SV1), ultimately forming colonies that were enriched with VPr+ vascular foci (Figure 1C).

Hemato-endothelial differentiation of hESCs in serum-free conditions is augmented by coculture with vascular feeder cells. (A) hESCs that were transduced with a vascular specific reporter transgene, VE-cadherin-GFP/mOrange (VPr-hESCs), and clonally selected were placed in serum-free differentiation coculture with primary ECs (HUVECs) that had been transduced with E4ORF1 cDNA and expanded. (B) Cocultures were sequentially stimulated with a series of cytokines and a small-molecule inhibitor of TGF-β signaling; a schematic view of the differentiation protocol is shown. (C) VPr hESCs were differentiated on E4ORF1+ ECs from 14 days followed by confocal microscopy; a wide-field view of vascular colonies is shown. (D-F) hESCs that were differentiated in coculture with E4ORF1+ ECs were fixed on days 3, 5, and 7 and stained for the markers Oct3/4 (red, D-E), Brachyury (green, E-F), and VEGFR2 (blue, F); E4ORF1+ ECs were labeled by CD31 (white). (G) The crude hESC-derived population on days 3-8 of differentiation was separated from feeder cells by flow cytometry, and relative levels of the transcripts Oct3/4, Brachyury, and VEGFR2 were measured. (H) Surface expression of VEGFR2 and SSEA3 was measured on hESC derivatives at multiple time points during differentiation on EC feeders (solid area curve), as well as hESCs differentiated in feeder-free conditions (black line), and hESCs differentiated on non-EC bone marrow stromal cells (bar graph, measured at day 8). (I-J) VPr-hESCs were clonally labeled with PGK-BFP so that differentiated derivatives could be distinguished from feeder cells (I). (J) Flow cytometry identified a significant portion of the BFP+ population that was positive for the VPr transgene and CD31. (K) VPr-hESCs that were clonally labeled with PGK-BFP were isolated at multiple time points during differentiation, and the percentage of hESC derivatives expressing both the VPr transgene and CD31 was measured. (L) Endothelial cells were FACS isolated from hESC differentiation cultures based on expression of the VPr-GFP transgene and plated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 on gelatin-coated tissue culture plastic. Time-lapse microscopy was performed over 5 days; 0-, 24-, 48-, and 72-hour time points are shown. (M) Commencing at day 13 during differentiation of VPr-hESCs on E4ORF1+ ECs, time-lapse confocal microscopy was performed over 3 days with addition of anti CD43-allophycocyanin antibody at 48 hours; 0-, 24-, 48-, and 50-hour time points are shown. (G-H) Error bars represent SD of experimental values performed in triplicate. (K) Error bars represent at least 6 replicates for each time point. (C-F) Lower panels: Higher power views of the dashed stroke box in the upper panel. (C,E insets) Bright-field view. (M insets) Magnified views of the stroke boxes. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Hemato-endothelial differentiation of hESCs in serum-free conditions is augmented by coculture with vascular feeder cells. (A) hESCs that were transduced with a vascular specific reporter transgene, VE-cadherin-GFP/mOrange (VPr-hESCs), and clonally selected were placed in serum-free differentiation coculture with primary ECs (HUVECs) that had been transduced with E4ORF1 cDNA and expanded. (B) Cocultures were sequentially stimulated with a series of cytokines and a small-molecule inhibitor of TGF-β signaling; a schematic view of the differentiation protocol is shown. (C) VPr hESCs were differentiated on E4ORF1+ ECs from 14 days followed by confocal microscopy; a wide-field view of vascular colonies is shown. (D-F) hESCs that were differentiated in coculture with E4ORF1+ ECs were fixed on days 3, 5, and 7 and stained for the markers Oct3/4 (red, D-E), Brachyury (green, E-F), and VEGFR2 (blue, F); E4ORF1+ ECs were labeled by CD31 (white). (G) The crude hESC-derived population on days 3-8 of differentiation was separated from feeder cells by flow cytometry, and relative levels of the transcripts Oct3/4, Brachyury, and VEGFR2 were measured. (H) Surface expression of VEGFR2 and SSEA3 was measured on hESC derivatives at multiple time points during differentiation on EC feeders (solid area curve), as well as hESCs differentiated in feeder-free conditions (black line), and hESCs differentiated on non-EC bone marrow stromal cells (bar graph, measured at day 8). (I-J) VPr-hESCs were clonally labeled with PGK-BFP so that differentiated derivatives could be distinguished from feeder cells (I). (J) Flow cytometry identified a significant portion of the BFP+ population that was positive for the VPr transgene and CD31. (K) VPr-hESCs that were clonally labeled with PGK-BFP were isolated at multiple time points during differentiation, and the percentage of hESC derivatives expressing both the VPr transgene and CD31 was measured. (L) Endothelial cells were FACS isolated from hESC differentiation cultures based on expression of the VPr-GFP transgene and plated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 on gelatin-coated tissue culture plastic. Time-lapse microscopy was performed over 5 days; 0-, 24-, 48-, and 72-hour time points are shown. (M) Commencing at day 13 during differentiation of VPr-hESCs on E4ORF1+ ECs, time-lapse confocal microscopy was performed over 3 days with addition of anti CD43-allophycocyanin antibody at 48 hours; 0-, 24-, 48-, and 50-hour time points are shown. (G-H) Error bars represent SD of experimental values performed in triplicate. (K) Error bars represent at least 6 replicates for each time point. (C-F) Lower panels: Higher power views of the dashed stroke box in the upper panel. (C,E insets) Bright-field view. (M insets) Magnified views of the stroke boxes. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

To define the kinetics of differentiation in coculture with E4ORF1+ ECs, hESC-derived cells were isolated at multiple time points and assessed by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1D-F), quantitative PCR (Figure 1G), and flow cytometry (Figure 1H-K). As expression of Oct3/4 transcript began decreasing after day 4 of differentiation, Brachyury transcripts increased, peaking at day 5 before dropping precipitously (Figure 1G), and this was followed by increased expression of VEGFR2, a marker of cardiovascular derivatives.22-24 Immunofluorescence data supported the trend identified by quantitative PCR (Figure 1D-F). Many hESC derivatives were Oct3/4 negative by day 3, and remaining Oct3/4+ cells were enriched at the border zone between E4ORF1+ ECs and the hESC colony (Figure 1D). At day 5, Oct3/4+ cells at the boundary between E4ORF1+ ECs and hESC derivatives were also Brachyury+ and began to migrate onto the E4ORF1+ EC feeder layer (Figure 1E). By day 7, VEGFR2 was observed in migratory cells that were in direct cellular contact with underlying E4ORF1+ ECs (Figure 1F). Collectively, these data showed a progressive loss of hESC pluripotency, mesoderm induction, and acquisition of a vascular signature.

To monitor acquisition of vascular cell fate, the surface phenotype of hESC derivatives was assessed by flow cytometry at multiple time points, focusing on the emergence of differentiated (SSEA3−) VEGFR2+ cells (Figure 1H). Starting at day 6 of differentiation, the majority of VEGFR2+ cells were SSEA3−, with near-complete absence of residual undifferentiated SSEA3+ cells by day 8. Compared with feeder-free conditions (Figure 1H hyphenated line), or cocultures with non-EC bone marrow stromal cells (Figure 1H right), E4ORF1+ ECs induced a larger proportion of SSEA3−VEGFR2+ hESC derivatives. To exclude E4ORF1+ EC feeders from measurements of the hESC-derived population, undifferentiated hESCs were clonally labeled with a constitutively expressed BFP (Figure 1I-K). After differentiation, the percentage of VPr+CD31+ cells among hESC derivatives (green, Figure 1I-J) was measured at 2-day intervals from day 12 to 18 (Figure 1K). Culture of the VPr+CD31+ population after isolation at day 14 revealed hematopoietic-like cells among cellular derivatives (Figure 1L and SV2), and round VPr+ cells were also observed within heterogeneous hESC differentiation cultures (Figure 1M). Time-lapse imaging of one such region was performed for 48 hours, followed by addition of a directly conjugated antibody against CD43 (Figure 1M; and SV3), positively labeling VPr+ cells and affirming their hematopoietic identity.

Hematopoietic derivatives of hESCs originate from hemogenic ECs

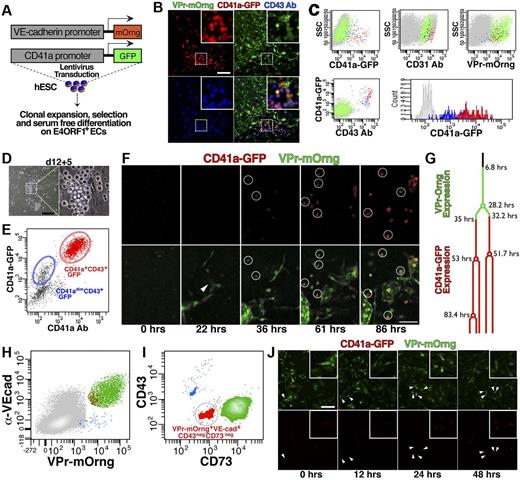

To provide spatiotemporal context for the specification of endothelial and/or hematopoietic identity during differentiation, the VPr-mOrange hESC line was transduced with an additional lentiviral reporter construct (Figure 2A) containing green fluorescent protein under control of a promoter fragment of human CD41a (CD41a-GFP), which is specifically expressed during early embryogenesis in precursors of definitive hematopoietic cells.25 After differentiation of this dual reporting hESC line on E4ORF1+ ECs, derivatives coexpressing both reporter transgenes and CD43 were evident (Figure 2B). Flow cytometric analysis showed coexpression of the CD41a-GFP transgene with CD43, as well as CD31 and VPr-mOrange (Figure 2C). Notably, after expansion on hESC-derived ECs for 5 days (Figure 2D-E), CD43+ cells that were not brightly positive for CD41a-GFP dimly expressed the transgene (blue, Figure 2C,E) but lacked surface expression of CD41a (Figure 2E). In contrast, CD41a-GFPbright cells were CD41a+ (red, Figure 2C,E). Live confocal imaging during differentiation (Figure 2F; and SV4 and 5) captured the onset of VPr-mOrange expression around day 11 of differentiation, and tracking of a putative hemogenic EC (Figure 2F-G) revealed the sequential induction of VPr-mOrange and CD41a-GFP expression.

Hematopoietic derivatives of transgenic hESCs express the CD41a-GFP and originate from VPr-mOrange+ hemogenic ECs. (A) hESCs that were transduced with the vascular specific reporter transgene (VPr-mOrange) as well as a hematopoietic specific transgene (CD41a-GFP) were placed in serum-free differentiation coculture with E4ORF1+ ECs (see “Methods”). (B) At day 14 of differentiation, cells were observed that expressed the VPr-mOrange (green) and CD41a-GFP (red) transgenes, and were labeled by an allophycocyanin-conjugated CD43-specific antibody (blue). (C) At day 14 of differentiation, cultures were labeled for flow cytometry with antibodies specific for CD31 and CD43; scatter plots showing the distribution of CD41a-GFP+/CD43+ (red), CD41a-GFP−/CD43+ (blue), and remaining VPr-mOrange+ (green) cells are shown. (D-E) CD43+ derivatives were isolated at day 12 and cultured for an additional 5 days in the presence of hematopoietic cytokines, followed by labeling with an antibody specific for CD41a; a scatter plot of CD41a-GFP versus CD41a antibody identifies derivatives that dimly (blue) or strongly (red) expressed the CD41a-GFP transgene. (F) The VPr-mOrange/CD41a-GFP hESC line was differentiated on E4ORF1+ ECs for 11 days, and then time-lapse confocal microscopy was performed over the next 4 days. Panels shown are time 0, the first indications of VPr-mOrange expression in an isolated EC (22 hours), when the VPr-mOrange+ cell noted at time 0 began to display discernible expression of the CD41a-GFP transgene (36 hours), and late time points at 61 and 86 hours as the double-positive population expands. (G) Lineage dendrogram of hemogenic EC progression with the onset of VPr-mOrange expression (green) and the onset of CD41a-GFP expression (red); cell divisions are marked by circles. (H-J) At day 14 of differentiation, hESC-derived ECs were isolated based on a VPr-mOrange+VE-cadherin+CD43−CD73− phenotype (red in panels H-I) and continuously monitored by confocal time-lapse microscopy for > 60 hours. (J) Zero-, 12-, 24-, and 48-hour time points with arrowheads indicating an EC undergoing EHT. (B,D,J insets) Magnified views. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Hematopoietic derivatives of transgenic hESCs express the CD41a-GFP and originate from VPr-mOrange+ hemogenic ECs. (A) hESCs that were transduced with the vascular specific reporter transgene (VPr-mOrange) as well as a hematopoietic specific transgene (CD41a-GFP) were placed in serum-free differentiation coculture with E4ORF1+ ECs (see “Methods”). (B) At day 14 of differentiation, cells were observed that expressed the VPr-mOrange (green) and CD41a-GFP (red) transgenes, and were labeled by an allophycocyanin-conjugated CD43-specific antibody (blue). (C) At day 14 of differentiation, cultures were labeled for flow cytometry with antibodies specific for CD31 and CD43; scatter plots showing the distribution of CD41a-GFP+/CD43+ (red), CD41a-GFP−/CD43+ (blue), and remaining VPr-mOrange+ (green) cells are shown. (D-E) CD43+ derivatives were isolated at day 12 and cultured for an additional 5 days in the presence of hematopoietic cytokines, followed by labeling with an antibody specific for CD41a; a scatter plot of CD41a-GFP versus CD41a antibody identifies derivatives that dimly (blue) or strongly (red) expressed the CD41a-GFP transgene. (F) The VPr-mOrange/CD41a-GFP hESC line was differentiated on E4ORF1+ ECs for 11 days, and then time-lapse confocal microscopy was performed over the next 4 days. Panels shown are time 0, the first indications of VPr-mOrange expression in an isolated EC (22 hours), when the VPr-mOrange+ cell noted at time 0 began to display discernible expression of the CD41a-GFP transgene (36 hours), and late time points at 61 and 86 hours as the double-positive population expands. (G) Lineage dendrogram of hemogenic EC progression with the onset of VPr-mOrange expression (green) and the onset of CD41a-GFP expression (red); cell divisions are marked by circles. (H-J) At day 14 of differentiation, hESC-derived ECs were isolated based on a VPr-mOrange+VE-cadherin+CD43−CD73− phenotype (red in panels H-I) and continuously monitored by confocal time-lapse microscopy for > 60 hours. (J) Zero-, 12-, 24-, and 48-hour time points with arrowheads indicating an EC undergoing EHT. (B,D,J insets) Magnified views. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

To focus on ECs that undergo EHT, we first set out to identify the population of hESC derivatives that includes hemogenic endothelium (SF1). We divided CD43−CD31+VPr+ ECs into fractions that were positive and negative for CD73, a mesenchymal marker that is specifically absent from hESC-derived hemogenic ECs.26 Indeed, CD73− cells generated significantly more hematopoietic derivatives than the CD73+ fraction (SF1a and SFb). To further define the phenotype of hESC-derived hemogenic ECs, VPr+CD31+CD73− cells were divided into populations that were positive and negative for CD34, a canonical marker of adult hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Limiting dilution analysis of CD34+ versus CD34− fractions revealed that hemogenic ECs occurred at a frequency of 1 in every 353 to 506 VPr+CD31+CD73−CD34+ cells. To show that EHT derives from conversion of cells with a bona fide EC surface phenotype, VPr+VE-cadherin+CD43−CD73− cells were isolated (Figure 2H-I) and observed by confocal time-lapse microscopy for 60 hours (Figure 2J; and SV6). A single EC maintained adherent morphology during 2 cell divisions before uniformly giving rise to round cells that expressed CD41a-GFP.

hESC-derived HPCs generate multiple lineage specific populations

The constituents of the hematopoietic system are broadly categorized into 3 progenitor cell types: erythroid/megakaryocytic, myeloid, and lymphoid. To define the phenotypic signatures displayed by hESC-derived hematopoietic cells, they were tested for surface expression of numerous lineage specific markers (Figure 3A-G). Although cells positive for lymphoid markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD19) were uniformly and consistently absent from differentiation cultures (data not shown), erythroid (Figure 3E), megakaryocytic (Figure 3F), and myeloid (Figure 3G) derivatives were observed among hematopoietic cells expanded on hESC-derived ECs. Specifically, 5 populations were distinguished within the pool of hESC-derived hematopoietic cells, identified by combinatorial expression of the surface markers CD14, CD15, CD33, CD41a, CD42a, CD43, CD45, CD61, CD71, and CD235a. Variable expression of these antigens identified the following unique populations: megakaryocytic, CD41a+CD42a+CD61+ (green, Figure 3A-F; SF2a); erythroid, CD71+CD235abright (yellow, Figure 3A-E; and SF2b); Lineage−, CD15−CD41a−CD45dimCD71− CD235a− (blue, Figure 3A-E; and SF2c); granulocytic, CD15+CD33dim (pink, Figure 3A-E,G; and SF2d); and monocytic, CD14+CD33brightCD45bright (red, Figure 3A-E,G; and SF2e).

The CD41a-GFP dimLineage− population is composed of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. (A-G) CD43+ cells were isolated from hESC differentiation at day 14 and cultured for an additional 5 days on hESC-derived ECs; flow cytometry was performed examining multiple parameters as shown in panels B through G. (E) Erythroid derivatives are indicated by colocalization of CD71 and CD235a. (F) Labeling of the CD41a fraction with CD42a and CD61 indicates megakaryocyte identity. (G) Labeling of the CD15+ and CD45bright populations with CD14 and CD33 indicates myeloid identity. (H) CD43+ cells were isolated from VPr-mOrange/CD41a-GFP hESCs at day 14 of differentiation and cultured for an additional 5 days on hESC-derived EC feeders, followed by labeling to distinguish Lineage− and Lineage+ populations; expression of CD41a-GFP transgene and CD41a surface antigen is shown for all populations. (I-O) CD41a-GFP dimLineage− cells indicated in panel H were collected for Megacult (I) and Methocult (J-O) colony assays. (J) The colony-forming potential of Lineage− cells was compared with Lineage+ populations, and the number of CFU-GEMM, CFU-E, and CFU-G/M were scored after 2 weeks. (L-O) The CD41a-GFP dimLineage− population was sorted as single cells directly into Methocult medium; after 15 days, clones were isolated and labeled and surface phenotype was assessed by flow cytometry. (J) Error bars represent SD among 3 replicates.

The CD41a-GFP dimLineage− population is composed of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. (A-G) CD43+ cells were isolated from hESC differentiation at day 14 and cultured for an additional 5 days on hESC-derived ECs; flow cytometry was performed examining multiple parameters as shown in panels B through G. (E) Erythroid derivatives are indicated by colocalization of CD71 and CD235a. (F) Labeling of the CD41a fraction with CD42a and CD61 indicates megakaryocyte identity. (G) Labeling of the CD15+ and CD45bright populations with CD14 and CD33 indicates myeloid identity. (H) CD43+ cells were isolated from VPr-mOrange/CD41a-GFP hESCs at day 14 of differentiation and cultured for an additional 5 days on hESC-derived EC feeders, followed by labeling to distinguish Lineage− and Lineage+ populations; expression of CD41a-GFP transgene and CD41a surface antigen is shown for all populations. (I-O) CD41a-GFP dimLineage− cells indicated in panel H were collected for Megacult (I) and Methocult (J-O) colony assays. (J) The colony-forming potential of Lineage− cells was compared with Lineage+ populations, and the number of CFU-GEMM, CFU-E, and CFU-G/M were scored after 2 weeks. (L-O) The CD41a-GFP dimLineage− population was sorted as single cells directly into Methocult medium; after 15 days, clones were isolated and labeled and surface phenotype was assessed by flow cytometry. (J) Error bars represent SD among 3 replicates.

The Lineage− population is composed of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors

Flow cytometry and cytospin identified erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid cells among HPC derivatives; however, the absence of markers on the Lineage− population (blue, Figure 3A-E,H) raised the possibility that this phenotype identified a multipotent progenitor. Moreover, cells within this population showed dim expression of the CD41a-GFP transgene (Figure 3H), and CD41a is transiently expressed in multipotent progenitors in vivo.2,25,27-29 To further define the place of each population in the hierarchy of embryonic hemogenesis, cells were segregated according to surface phenotype (excluding the CD45bright population) and plated as single clones or groups of 10 cells on hESC-derived EC feeders (SF3). These experiments revealed that, whereas the CD15+CD33dim population (pink, SF3a and SF3b) mostly gave rise to myeloid cells and the CD71+CD235abright (yellow, SF3a and SF3d) and CD41a+CD42a+CD61+ (green, SF3a and SF3e) populations mostly generated erythroid and/or megakaryocytic derivatives, the Lineage− population (blue, SF3a and SF3c) was capable of generating both myeloid and erythro-megakaryocytic cells.

To assay their functional potential, in vitro colony formation was performed for each hESC-derived hematopoietic population using Megacult (Figure 3I) and Methocult (Figure 3J-O) assays. Lineage− cells formed CD41a+ colonies in collagen-based Megacult assay (Figure 3I) and yielded significantly more colonies in Methocult medium than other populations (Figure 3J). Although the majority of CFUs formed in Methocult from Lineage− cells were of the CFU-GM variety, CFU-GEMM and CFU-E were also observed; and although CD71+CD235abright cells yielded mostly CFU-E colonies, the CD15+CD33dim group generated only few CFU-GM. Cytospins of Methocult preparations revealed cellular morphology indicative of distinct myeloid derivatives, containing a mix of monocyte/macrophage and granulocyte precursors (Figure 3K). In contrast, Methocult cultures of the CD15+CD33dim and CD14+CD33brightCD45bright populations showed exclusively monocyte/macrophage morphology (SF4). To affirm that the diverse phenotypic derivatives obtained in these experiments were clonally derived from single multipotent progenitors within the Lineage− population, single CD41a-GFPdimLineage− cells were deposited in Methocult medium (Figure 3L-O). Clonal outgrowth was observed at a frequency of 13.9% (±2.2, 288 replicates), and the morphology and surface phenotype of CFUs varied from homogeneous colonies of putative monocytes or granulocytes (Figure 3L and M, respectively), to heterogeneous groups of mixed GM (Figure 3N) or GEMM (Figure 3O) phenotype.

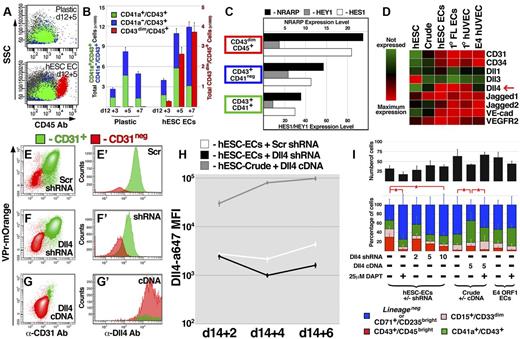

Up-regulation of Dll4 ligand in hESC-derived EC feeders promotes myeloid differentiation of HPCs

During embryogenesis, HPCs migrate between multiple microenvironments,5 each endowed with a unique signaling milieu. As such, expansion and maturation of hemogenic progenitors may involve molecular inputs from defined tissue beds. The association of HPCs with ECs during their specification suggested that the vascular niche provides trophic factors to foster proliferation and/or differentiation. Indeed, when CD43+ cells were isolated at day 12 and expanded on hESC-derived EC feeders, a significant proportion of cells differentiated to the CD14+CD33brightCD45bright phenotype; however, these cells were almost completely absent among derivatives expanded in feeder-free conditions (Figure 4A-B). Our group and others have demonstrated that Notch ligands expressed by ECs safeguard self-renewal of long-term repopulating HPCs derived from adult mice.19,21 In contrast, coculture with hESC-derived ECs induced myeloid differentiation of Lineage− HPCs, and RNA sequencing of lineage committed populations (Figure 4C) revealed that, in CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells, there was increased expression of NRARP and HES1, both of which are targets of Notch signaling during lymphoid differentiation of human cord blood progenitors.30 To define the molecular contribution from hESC-derived ECs toward myeloid specification of Lineage− HPCs, the CD43+ population was isolated and cultured in various conditions.

Expression of Dll4 ligand on vascular feeder cells specifically promotes myeloid differentiation of HPCs. (A-B) The CD43+ population was isolated from hESC differentiation cultures at day 12 and cultured for an additional 7 days in either the absence (plastic) or presence (hESC EC) of VPr+ EC feeders; scatter plots of the derivative populations (A) are shown at day 3 and 5 after isolation, and the distributions of CD41a+CD43+, CD41a−CD43+, and CD43dimCD45bright populations are quantified in panel B. (C) RNA sequencing was performed on the CD41a+CD43+, CD41a−CD43+, and CD43dimCD45bright populations; expression levels of NRARP, HES1, and HEY1 are shown. (D) RNA sequencing was performed on undifferentiated hESCs, crude non-EC derivatives of hESC differentiation, VPr+CD31+ ECs, primary fetal liver ECs from aborted human fetus, neonatal umbilical cord ECs (HUVEC), and E4ORF1 ECs; a heat map describing the expression of vascular specific markers and Notch ligands is shown. (E-G) VPr+ ECs were isolated from hESC differentiation at day 14 and incubated with lentivirus encoding control (scrambled) or Dll4 shRNA. Crude non-EC derivatives were also isolated and incubated with lentivirus encoding Dll4 cDNA. Flow cytometric analysis defined the expression of the VPr-mOrange transgene, CD31, and Dll4 in cultured derivatives after 6 days. (H) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) value of Dll4 surface expression was plotted for cells described in panels E-G at 2, 4, and 6 days after addition of lentivirus. (I) At 48 hours after addition of lentivirus, cells described in panels E-H were washed with culture medium, and GFP+CD43+ cells isolated from day 16 of differentiation were added at 10 cells per well of a 48-well dish. After 4 days, the total number of GFP-derivatives (black bar), as well as the percentage of CD43dimCD45bright, CD15+CD33dim, CD41a+CD43+, and CD71+CD235abright/Lineage− cells was measured. (I) The numbers indicate the concentration of lentivirus particles added to cells in ng/mL. (B,H) Error bars represent SD among 3 replicates. (I) Error bars represent SD among 8 replicates. *P < .05.

Expression of Dll4 ligand on vascular feeder cells specifically promotes myeloid differentiation of HPCs. (A-B) The CD43+ population was isolated from hESC differentiation cultures at day 12 and cultured for an additional 7 days in either the absence (plastic) or presence (hESC EC) of VPr+ EC feeders; scatter plots of the derivative populations (A) are shown at day 3 and 5 after isolation, and the distributions of CD41a+CD43+, CD41a−CD43+, and CD43dimCD45bright populations are quantified in panel B. (C) RNA sequencing was performed on the CD41a+CD43+, CD41a−CD43+, and CD43dimCD45bright populations; expression levels of NRARP, HES1, and HEY1 are shown. (D) RNA sequencing was performed on undifferentiated hESCs, crude non-EC derivatives of hESC differentiation, VPr+CD31+ ECs, primary fetal liver ECs from aborted human fetus, neonatal umbilical cord ECs (HUVEC), and E4ORF1 ECs; a heat map describing the expression of vascular specific markers and Notch ligands is shown. (E-G) VPr+ ECs were isolated from hESC differentiation at day 14 and incubated with lentivirus encoding control (scrambled) or Dll4 shRNA. Crude non-EC derivatives were also isolated and incubated with lentivirus encoding Dll4 cDNA. Flow cytometric analysis defined the expression of the VPr-mOrange transgene, CD31, and Dll4 in cultured derivatives after 6 days. (H) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) value of Dll4 surface expression was plotted for cells described in panels E-G at 2, 4, and 6 days after addition of lentivirus. (I) At 48 hours after addition of lentivirus, cells described in panels E-H were washed with culture medium, and GFP+CD43+ cells isolated from day 16 of differentiation were added at 10 cells per well of a 48-well dish. After 4 days, the total number of GFP-derivatives (black bar), as well as the percentage of CD43dimCD45bright, CD15+CD33dim, CD41a+CD43+, and CD71+CD235abright/Lineage− cells was measured. (I) The numbers indicate the concentration of lentivirus particles added to cells in ng/mL. (B,H) Error bars represent SD among 3 replicates. (I) Error bars represent SD among 8 replicates. *P < .05.

First, to test whether exogenously added cytokines contributed to induction of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright phenotype, media additives were omitted from cocultures during expansion/differentiation of HPCs on hESC-derived EC feeders (SF5). Although inclusion of hematopoietic cytokines SCF, Flt3 ligand, and thrombopoietin resulted in increased hematopoietic derivatives at the population level, the amount of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells was not significantly reduced on exclusion of any one exogenous media additive.

To determine whether lineage progression observed in our system occurred in response to generic trophic factors or signals specifically endowed by hESC-derived ECs, we compared differentiation of HPCs cocultured with a variety of feeder cell types (SF6), including VPr+ ECs and crude non-EC derivatives from hESC differentiation, freshly isolated HUVECs, fetal liver ECs from aborted human fetuses, and E4ORF1+ ECs. Notably, coculture yielded more total cells than tissue-culture plastic; however, there was no significant difference in total hematopoietic derivatives cultured on different feeder cell types. And although coculture with hESC-derived ECs, primary HUVECs, and fetal liver ECs elicited an increased proportion of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells, the percentage of this population was not significantly greater in coculture with crude non-ECs or E4ORF1+ ECs than it was on tissue culture plastic alone.

The differential capacity for EC feeder cells to elicit myeloid differentiation suggested that they exhibit unique expression profiles. Indeed, RNA sequencing showed that the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 (Dll4) was highly expressed on hESC-derived ECs, fetal liver ECs, and primary HUVEC (cell types that promoted increased myeloid differentiation of HPCs), and weakly expressed in feeder cell types (E4ORF1 HUVEC and hESC-derived non-EC crude) that did not significantly increase myeloid differentiation (Figure 4D). To explore the hypothesis that activation of Notch signaling via Dll4 mediates differentiation of the Lineage− population to CD14+CD33brightCD45bright identity, lentiviral shRNA targeted against Dll4 and cDNA encoding Dll4 were used to knock down or increase expression on hESC-derived EC feeders or crude non-ECs, respectively (Figure 4E-I; and SF7). On addition of the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT, the proportion of myeloid derivatives was sharply reduced, and with an increasing dose of lentivirus encoding Dll4 shRNA, a progressive decrease in the percentage of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells was observed (Figure 4I). In contrast, enforced expression of Dll4 in non-EC crude derivatives of hESC differentiation induced an increased percentage of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells, and this effect was abrogated by DAPT.

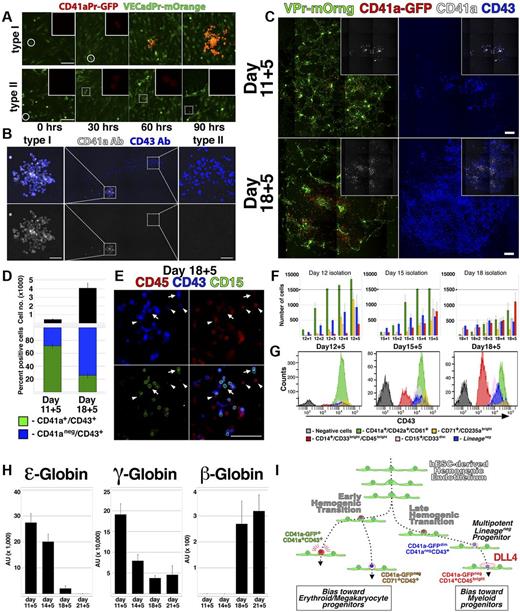

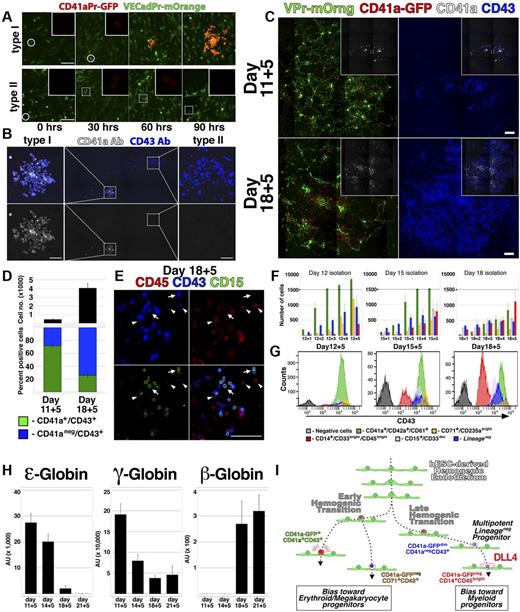

Lineage potential of hemogenic ECs varies with the stage of hESC differentiation

The restricted lineage potential exhibited by the CD41a-GFPbrightCD41a+CD43+ population (Figure 3J; supplemental Figure 3E, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) was consistent with in vitro studies conducted with hESCs17 ; however, numerous in vivo studies have shown that CD41a marks a precursor of multipotent hematopoietic cells.2,25,27-29 To define the dynamics of CD41a expression during hemogenesis, VPr-mOrange+CD31+CD43− ECs from day 12 of differentiation were monitored by confocal time-lapse microscopy (Figure 5A-B; and SV7 and SV8). These video captures demonstrated the direct conversion of single adherent VPr-mOrange+ CD41a-GFP− ECs to round VPr-mOrange+ CD41a-GFP+ HPC derivatives. Moreover, by observing multiple foci of EC to HPC conversion, 2 distinct types of EHT were noted. Whereas one type of conversion was followed by sustained and robust expression of the CD41a-GFP transgene clonally in all derivatives (Figure 5A; and SV7, type I), another coincided with weak expression of the CD41a-GFP transgene (Figure 5A; and SV8, type II). After 111 hours, samples were labeled using antibodies specific for CD41a and CD43 (Figure 5B), revealing a correlation of weakly expressing derivatives with the CD41a−CD43+ surface phenotype, and robustly expressing derivatives with the megakaryocytic CD41a+ phenotype. Time-lapse imaging and live immunolabeling of another group of cells revealed that at least 3 distinct phenotypic signatures could be generated from single hematopoietic cells downstream of EC to HPC conversion (supplemental Video 9; supplemental Figure 8). In contrast, CD41a-GFPbrightCD41a+ cells were clustered monotypic clones. These results suggested that hESC-derived hemogenic ECs may be composed of 2 subtypes that clonally generate either megakaryocyte lineage-restricted (type I, CD41a-GFPbrightCD41a+CD43+) or multipotent Lineage− (type II, CD41a-GFPdimCD41a−CD43+) progenitors.

Lineage potential of hemogenic ECs varies with the stage of hESC differentiation. (A) Single time points from live confocal image capture shown in SV7 and 8 are shown at 30-hour intervals for type I and type II hemogenic conversion. (B) At the end of image capture, the time-lapse cultures shown in supplemental Videos 7 and 8 were labeled with antibodies specific for CD41a and CD43; staining of type I and type II hemogenic derivatives is shown. (C-E) VPr+CD73−CD34+ ECs were isolated from differentiation of VPr-mOrange/ CD41a-GFP hESCs at day 11 and day 18 and cultured in parallel under continuous observation by confocal microscopy (SV10); after 5 days, cultures were labeled with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies to identify CD41a and CD43 cells. (D) The relative surface area of total CD43+ cells (black) and the proportion of CD41a+CD43+ (green) to CD41a−CD43+ (blue) populations were calculated using ImageJ Version 1.43 software. (E) Cultures that were recorded in the time-lapse video were also labeled with antibodies to CD15 (green) and CD45 (red); arrows indicate CD15+ cells; and arrowheads, CD43dimCD45+ cells. (F-G) CD43+ cells were isolated from parallel VPr-hESC differentiation cultures at multiple 12-, 15-, and 18-day time points and expanded in coculture with hESC-derived ECs for an additional 5 days. Cells were labeled each day with antibodies to identify Lineage− and Lineage+ populations, and their distribution was quantified at each day during expansion. (H) Hematopoietic progenitors were isolated from hESC differentiation cultures at variable time points and expanded for 5 days; after expansion, CD71+ cells were isolated, and expression of ϵ, γ, and β globins was measured by quantitative PCR. (I) A schematic representation of distinct early and late phases of EHT during hESC differentiation. (D) Error bars represent SD between duplicate samples. (F,H) Error bars represent SD among triplicates. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Lineage potential of hemogenic ECs varies with the stage of hESC differentiation. (A) Single time points from live confocal image capture shown in SV7 and 8 are shown at 30-hour intervals for type I and type II hemogenic conversion. (B) At the end of image capture, the time-lapse cultures shown in supplemental Videos 7 and 8 were labeled with antibodies specific for CD41a and CD43; staining of type I and type II hemogenic derivatives is shown. (C-E) VPr+CD73−CD34+ ECs were isolated from differentiation of VPr-mOrange/ CD41a-GFP hESCs at day 11 and day 18 and cultured in parallel under continuous observation by confocal microscopy (SV10); after 5 days, cultures were labeled with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies to identify CD41a and CD43 cells. (D) The relative surface area of total CD43+ cells (black) and the proportion of CD41a+CD43+ (green) to CD41a−CD43+ (blue) populations were calculated using ImageJ Version 1.43 software. (E) Cultures that were recorded in the time-lapse video were also labeled with antibodies to CD15 (green) and CD45 (red); arrows indicate CD15+ cells; and arrowheads, CD43dimCD45+ cells. (F-G) CD43+ cells were isolated from parallel VPr-hESC differentiation cultures at multiple 12-, 15-, and 18-day time points and expanded in coculture with hESC-derived ECs for an additional 5 days. Cells were labeled each day with antibodies to identify Lineage− and Lineage+ populations, and their distribution was quantified at each day during expansion. (H) Hematopoietic progenitors were isolated from hESC differentiation cultures at variable time points and expanded for 5 days; after expansion, CD71+ cells were isolated, and expression of ϵ, γ, and β globins was measured by quantitative PCR. (I) A schematic representation of distinct early and late phases of EHT during hESC differentiation. (D) Error bars represent SD between duplicate samples. (F,H) Error bars represent SD among triplicates. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

The different forms of EHT exhibited during hESC differentiation may reflect discreet waves of lineage potential that have been described during mammalian embryogenesis. Indeed, of 9 observed conversion events derived from a population of day 12 VPr+CD31+CD43− ECs (supplemental Videos 7 and 8), the majority (7 of 9) were of the type I megakaryocyte lineage-restricted variety. To determine whether hESC-derived hemogenic ECs exhibit variable potential at different points during differentiation, VPr+CD31+CD73− ECs derived from the VPr-mOrange/ CD41a-GFP line were isolated from day 11 or day 18 of differentiation and observed continuously by time-lapse microscopy (Figure 5C-E; and SV10). Although the same amount of cells were seeded, ECs from day 18 generated a significantly greater yield of CD43+ cells after111 hours of culture (Figure 5C-D); however, the proportion of CD41a+CD43+ to CD41a−CD43+ cells was higher among cells isolated at day 11. In addition, lineage-specific populations, as denoted by CD15 and CD45 surface labeling (Figure 5E), were observed at higher frequency at the later time point.

To stratify the relative lineage potential of HPCs as hESC differentiation progresses, cells that were differentiated in parallel from the same parental culture were isolated at different time points and assayed (Figure 5F-G). Among derivatives of CD43+ cells cocultured for 5 days on hESC-derived EC feeders, there was a shift at later time points in the proportion of cells that assumed erythro-megakaryocytic versus myeloid identity. Specifically, CD43+ cells isolated at day 12 of hESC differentiation were relatively biased to specification and/or expansion of cells with CD41a+CD42a+CD61+ and CD71+CD235abright surface phenotype, whereas cells isolated at day 15 and 18 were biased toward CD14+CD33brightCD45bright myeloid phenotype.

Previous studies have shown that hESC-derived hematopoietic cells undergo globin switching with extended culture31 and erythroid cells expressing adult (beta) globins are identifiable at later stages of hESC differentiation.32 To test whether the shift in lineage bias observed in Figure 5C through G coincided with changes in globin levels, we examined the expression of ϵ (embryonic), γ (fetal), and β (adult) globins in CD71+ erythroid cells that were isolated at different time points during differentiation and expanded for 5 days on day 15 hESC-derived EC feeders (Figure 5H). At early time points, ϵ and γ globins were highly expressed and β globin was not detected. At later time points, however, ϵ and γ globins were reduced, and the expression of β globins became more pronounced. This change in globin expression with advancing temporal stage of differentiation suggested a shift in intrinsic potential in the hESC-derived HPC population that recapitulates successive waves of lineage potential that are observed in vivo.

Discussion

In human embryogenesis, the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region generates long-term engraftable hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) beginning at ∼ 4 weeks; and although erythroid progenitors are observed in the fetal liver as early as day 30, cells with multilineage potential have not been noted there until week 13, and long-term culture initiating cells have not been found in the placenta before week 8.33-37 Indeed, a recent human study mapped the spatiotemporal and qualitative development of hematopoietic cells during embryogenesis and suggested a hierarchy in which hematopoietic progenitors become progressively more distributed among tissues with advancing development of the embryo,38 culminating in bona fide HSCs evident in the bone marrow. However, the phenotypic progression that embryonic and fetal HPCs undergo during these stages is unknown. The sustained live imaging, tracking, and clonal analyses of hematopoietic populations in this study provide a framework of early hematopoietic specification (Figure 5I) that integrates in vitro experiments using hESCs17 with in vivo studies.2,25,27-29

Previous work has identified the CD41a+CD43+ population as erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors17 ; however, it has been posited that these cells derived from a more primitive CD34+VEGFR2+ non-EC progenitor and that CD41a−CD43+ multipotent progenitors emerge later from CD34+VEGFR2+VE-cadherin+ hemogenic ECs. Our results showed that Lineage− cells were capable of generating lineage restricted CD41a+CD42a+CD61+ derivatives. Furthermore, we demonstrated that both Lineage− and CD41a+ clones originated directly from single adherent hESC-derived VE-cadherin+VPr-mOrange+ ECs and that the intrinsic potential of HPCs to generate erythro-megakaryocytic versus myeloid cells varied with the timing of EC to HPC conversion.

The live image capture of single ECs converting to hematopoietic identity also reconciled data from hESC studies with those using mouse embryonic models.2,25,29 It has been shown that definitive HSCs arise from a population of CD41a+ cells; however, the CD41a+ fraction of hESC differentiation cultures has been shown to exhibit restricted differentiation potential. We have demonstrated that Lineage− HPCs weakly express the CD41a-GFP transgene after transition from adherent hemogenic endothelial progenitors. Indeed, Lineage− cells maintained weak expression of the transgene but lacked surface expression unless they ultimately differentiated to CD41a+ megakaryocytic progenitors. These results are supported by in vivo studies in zebrafish28 and mouse,29 showing that low CD41a expression levels mark long-term reconstituting HSCs and that all lymphomyeloid lineages of the adult are derived from a CD41a-expressing cell. However, CD41a-GFPdimLineage− cells did not show the same potential for in vivo engraftment exhibited by definitive HSCs isolated from mouse and human fetal tissues. Indeed, numerous attempts to differentiate hESC-derived HPC populations into lymphoid cells in vitro, or to engraft them into immunocompromised NOD/SCID IL2γRnull mice, failed (data not shown). Nevertheless, the reduced activity of the CD41a-GFP transgene in the Lineage− population may reflect the weak and/or ancestral expression of CD41a exhibited by hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in vivo.

In mouse embryos, classification of hemogenesis has been segregated into 3 distinct waves, as defined by the site of origin and lineage potential of hematopoietic cells in question.39 First, a “primitive” population of cells emerges in the yolk sac and generates large nucleated erythroid cells and megakaryocytes. Next, a wave of “definitive” hematopoietic progenitors emerges at multiple intra- and extra-embryonic sites, generating erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid lineages. Finally, hemogenic ECs in the AGM region give rise to HSCs capable of long-term engraftment and multilineage reconstitution. Based on their lack of in vivo engraftment or lymphoid differentiation potential and their temporal bias toward myeloid fate at later stages of hESC differentiation, the Lineage− progenitors described in this study are probably an hESC-derived correlate of “definitive” erythroid/myeloid progenitors.

Evidence in mouse has suggested that at least 2 distinct types of hemogenic endothelium exist10 : one arising from a TEK+ population and giving rise to an early wave of definitive erythroid/myeloid progenitors, and another that stems from Sca1+ cells and generates definitive HSCs. This suggests that the multipotent Lineage− population may derive from human correlates of mouse TEK+ hemogenic progenitors. However, a homolog of Sca1 does not exist in humans, thus precluding comparison of hESC-derived hemogenic subpopulations based on expression of TEK versus Sca1.

Distinct populations of HPCs arise within specific tissues in vivo and are presumably supported by paracrine factors supplied by the niche; however, hESC differentiation cultures lack the anatomic context to identify and/or distinguish hemogenic compartments. Nevertheless, vascular ECs augment stem cell expansion and organ regeneration in vitro and in vivo19-21 and are a probable source of trophic factors40 that affect HPC specification and maturation during embryogenesis. The role for Dll4 in enhancing differentiation of CD14+CD33brightCD45bright cells (Figure 4) elucidated EC-derived Notch signaling as a modulator of hematopoietic lineage progression. Yet it is unclear whether modulation of Dll4 signaling in this system directly affected lineage progression of hESC-derived HPCs or mediated increased myeloid differentiation via secondary effects of Notch signal perturbation on hESC-derived EC feeders. Similarly, whether the high level of myeloid cells downstream of Notch signal activation resulted from increased self-renewal of the myeloid progenitor pool or greater induction of myeloid differentiation remains unknown. Experiments in zebrafish41 have shown that somite-specific expression of Notch ligands is required for definitive hematopoiesis, and Notch activation has been shown to play a role in the differentiation of T cells from human cord blood.30 However, null mutation of Notch1 or Notch2 receptors does not adversely affect the colony-forming activity of yolk sac erythroid/myeloid progenitors in vivo.42 Yet it is possible that the Lineage− population we identified may be a correlate of erythroid/myeloid progenitors that arise outside the yolk sac and are induced to myeloid fate by up-regulation of Notch ligands on vascular ECs.

The differentiation of human pluripotent cells to authentic HPCs that match the in vivo potential of definitive hematopoietic stem cells demands close examination of intermediate stages of hematopoietic ontogeny as well as the molecular stimuli that mediate progression between them. This study demonstrates that hESC-derived ECs not only generate distinct waves of hemogenic endothelium exhibiting variable lineage potential but also establish a vascular niche that directs and sustains expansion and differentiation of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. By defining phenotypic intermediates involved in early hemogenic ontogeny, along with specific paracrine factors within the vascular niche, this work provides an important experimental foundation for efforts to generate functional and engraftable long-term repopulating hematopoietic cells from human pluripotent stem cells.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

D.J. and S.R. were supported by the Empire State Stem Cell Board and the New York State Department of Health (grants C024180, C026438, and C026878), the Qatar National Priorities Research Foundation (NPRP08-663-3-140) and the Qatar Foundation Biomedical Research Program, Ansary Stem Cell Institute, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Howard Hughes Funding

Authorship

Contribution: S.R. interpreted results and wrote the paper; C.C.K. performed cell culture experiments and interpreted results; J.M.B. contributed reagents and performed experiments; M.G. prepared lentivirus particles for gene transduction; E.G. contributed reagents and performed Megacult colony assays; R.L., P.J., and B.-S.D. performed experiments; Q.Z. performed initial derivation of hESC lines and expanded/archived transgenic hESC lines; J.X. prepared samples for RNA sequencing; O.E. performed alignment and analysis of RNA sequencing data; N.Z. performed initial derivation of hESC lines; Z.R. contributed human embryos for initial derivation of hESC lines; M.S. assisted with interpretation of data; J.A.R. contributed reagents and interpreted results; and D.J. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daylon James, Department of Genetic Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, 1300 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: djj2001@med.cornell.edu.