Key Points

Adoptive transfer of autologous lentiviral-engineered T cells expressing an antisense is safe in chronic HIV infection.

Conditionally replicating lentiviral vector was associated with antiviral effects in patients as assessed by viral evolution and viral load.

Abstract

We report the safety and tolerability of 87 infusions of lentiviral vector–modified autologous CD4 T cells (VRX496-T; trade name, Lexgenleucel-T) in 17 HIV patients with well-controlled viremia. Antiviral effects were studied during analytic treatment interruption in a subset of 13 patients. VRX496-T was associated with a decrease in viral load set points in 6 of 8 subjects (P = .08). In addition, A → G transitions were enriched in HIV sequences after infusion, which is consistent with a model in which transduced CD4 T cells exert antisense-mediated genetic pressure on HIV during infection. Engraftment of vector-modified CD4 T cells was measured in gut-associated lymphoid tissue and was correlated with engraftment in blood. The engraftment half-life in the blood was approximately 5 weeks, with stable persistence in some patients for up to 5 years. Conditional replication of VRX496 was detected periodically through 1 year after infusion. No evidence of clonal selection of lentiviral vector–transduced T cells or integration enrichment near oncogenes was detected. This is the first demonstration that gene-modified cells can exert genetic pressure on HIV. We conclude that gene-modified T cells have the potential to decrease the fitness of HIV-1 and conditionally replicative lentiviral vectors have a promising safety profile in T cells. This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as number NCT00295477.

Introduction

Genetic modification of T lymphocytes to disrupt the HIV virus replication cycle offers a promising alternative to life-long antiviral therapy.1 To evaluate the effects of such interventions in the current era, in which drug treatment failure patients are not common, most studies transiently discontinue antiretroviral therapy (ART) to evaluate the new viral set point after an intervention in what has been called “analytical treatment interruption” (ATI). It is well established that HIV RNA levels in the plasma predict outcome in patients with chronic HIV infection.2 A 1-log reduction in the viral set point results in an approximate doubling of the time to progression to AIDS, suggesting that reduction in viral load without complete suppression has significant therapeutic benefit.3

One approach to HIV therapy based on gene transfer employs VRX496, an HIV-1–based lentiviral vector expressing a 937-base antisense gene complementary to HIV env. Expression is under the control of the native HIV long terminal repeat (LTR),4 so infection with HIV and the resulting Tat expression transactivates VRX496 to up-regulate antisense expression. Because VRX496 retains HIV cis-acting elements required for replication, VRX496 can potentially be mobilized by HIV infection and spread to new CD4 T cells. The presence of VRX496 proviruses in cells blocks HIV replication in vitro.5-7 Preclinical studies indicated that HIV evolution in the antisense-targeted region in the presence of VRX496 was associated with deletions and A → G transitions, suggesting that the mechanism of action of the antisense was mediated by the host adenosine deaminase enzyme4,8,9 and caused production of replication-impaired HIV.

We previously reported results after a single IV infusion of VRX496-containing CD4 T cells (VRX496-T; trade name, Lexgenleucel-T) in 5 patients failing ART.6 The infusion was safe and associated with improved CD4 counts, persistent gene transfer, no evidence of insertional mutagenesis, and self-limited mobilization of the vector in 4 of 5 patients. In 1 patient, a decrease of almost 2 Log10 in viral load was observed. We hypothesized that multiple infusions of gene-modified cells in earlier stage patients with well-controlled viral loads would improve the persistence of VRX496-T and enhance the therapeutic effect. We report herein the results of a multiple infusion trial of VRX496-T. In patients with well-controlled HIV infection, a significant decrease in viral load set point was observed after ATI, which was correlated with antisense pressure on the virus, but not with enhanced HIV-specific immune responses. Unexpectedly, multiple infusions did not enhance the persistence of VRX496-T. The data in this study support the safety and rationale for continued development of gene-based cell therapy for HIV and demonstrate a favorable safety profile of lentiviral vector gene therapy in T cells.

Methods

Lentiviral vector and cell manufacturing

Vector was manufactured by transient transfection using a 2-plasmid production system as described previously.6,10 Cell manufacturing was performed as described previously,6 with the exception that retronectin was not used for transduction and the Wave Bioreactor (GE Life Sciences) was used to generate the required number of cells.

Patients and clinical procedures

The study was conducted at the MacGregor Clinic of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA, and at the Jacobi Medical Center in Bronx, NY. The study (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as number NCT00295477) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review boards and biosafety committees of both institutions, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA; Center for Biologics Evaluation Review), and the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee and Department of AIDS. The study enrolled HIV-infected subjects ≥ 18 years of age with undetectable viral loads by ultrasensitive assay (typically < 20 copies/mL) and a CD4 cell count > 450 cells/mL at screening who were on a stable ART regimen and were willing to continue their regimen for the duration of the study and to undergo ATI after multiple infusions of VRX496-T. Excluded were recent HIV seroconverters; subjects with a history of cancer (other than treated basal or squamous cell carcinoma), congestive heart failure, pregnancy, or hepatitis B or C infection; prior recipients of HIV vaccines; and subjects with significant laboratory abnormalities, a positive VSV-G serology, or those using steroids or any other immunomodulators. Also excluded were subjects with allergy or hypersensitivity to study product excipients (human serum albumin, DMSO, and dextran).

T-cell infusions were administered biweekly at weeks 0, 2, and 6, with a safety evaluation at weeks 5-8, followed by a second cycle of infusions at weeks 9, 11, and 13. Thirteen patients with detectable VRX496-T underwent ATI 4 or 5 weeks after the last infusion. To avoid the generation of resistant HIV strains, patients on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) discontinued NNRTIs first and then, within 48 hours, discontinued other ARVs because NNRTIs have been reported to have longer persistence in vivo. For patients receiving 6 infusions, ATI was initiated at study week 18, and for patients receiving 3 infusions, ATI was initiated at week 10. Patients were evaluated at study weeks 20 and 22 or weeks 12 and 14 for patients receiving the 6 or 3 infusions, respectively, and then every 4 weeks thereafter. Patients would continue on ATI until they met the requirement for reinstatement of ART under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines at the time (HIV-1 RNA ≥ 100 000 copies/mL 3 consecutive times or a confirmed CD4 T-cell count of < 350 cells/mm3 or a cumulative drop of > 50% from baseline). The kinetics of viral rebound during ATI has been well characterized, typically occurring within 2-4 weeks after discontinuation of ART drugs.11 The criteria for the resumption of ART was a confirmed HIV-1 RNA ≥ 100 000 copies/mL or a confirmed CD4+ cell count of < 350 cells/mm3 or a cumulative decrease in CD4 counts of > 50% from baseline, in accordance with DHHS guidance at the time. After resumption of ART, subjects were followed monthly until their HIV RNA viral load became undetectable.

Primary end points of the study were safety, effects of infusion on viral load before ATI, effects on the timing of viral recrudescence and set point during ATI, and the change in CD4 T-cell counts from baseline to ATI. The original planned sample size for the study was 18 patients, which would provide sufficient power to detect a difference of 11 days in the time to virus recrudescence after AIT. Of the first 7 patients who underwent ATI, none had a delay in time to recrudescence, indicating that either there was no effect of the cells or that the time to viral recrudescence was not an optimal surrogate end point for evaluating efficacy. However, of the 7 patients, 3 remained off of ART long enough to establish a new viral load set point, all 3 had decreases in their set point that were more than their historic values measured before initiating ART. Therefore, we took an adaptive approach to the study design and continued enrolling patients with a modified end point of change in viral load set point from historic baseline. Baseline CD4 counts were taken as an average of the week −2 and day 0 CD4 counts (screen values were not used to avoid the regression to the mean phenomenon). Set points after ATI were taken as an average of weeks 10 and 14, which were the visits on the protocol that best fit with AIDS Clinical Trial Group standards.11,12 Historic viral load set points were derived from the average of all available values before the initiation of ART (supplemental Table 2, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Viral load assays used included the Roche Amplicore QNT PCR, Roche Cobas TaqMan ampliprep PCR, Versant branched DNA assay, or the Smith Kline Beecham PCR assay as indicated in supplemental Table 2. Secondary end points included evaluation of the persistence and trafficking of VRX496-T in peripheral blood and in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), evaluation of T-cell immune response measured by ELISPOT response to different mitogens, and measurements of TCR diversity.

Gene transfer and antiviral effects were also assessed by viral sequence evolution, vector integration site locations, and HIV sequences in VRX496-modified T cells. Control samples after treatment interruption were derived from randomized study NCT0051818.13 Detailed information about the samples evaluated for viral evolution are described in detail in supplemental Table 5.

After completion of the study intervention period, just after 1 year after infusion, all subjects are being monitored for delayed adverse events possibly related to gene transfer, as recommended in FDA guidelines, on a biannual basis for 5 years after infusion and then annually until 15 years after infusion.

Additional methods

For more details, see supplemental Methods.

Results

Study design, manufacturing, and safety

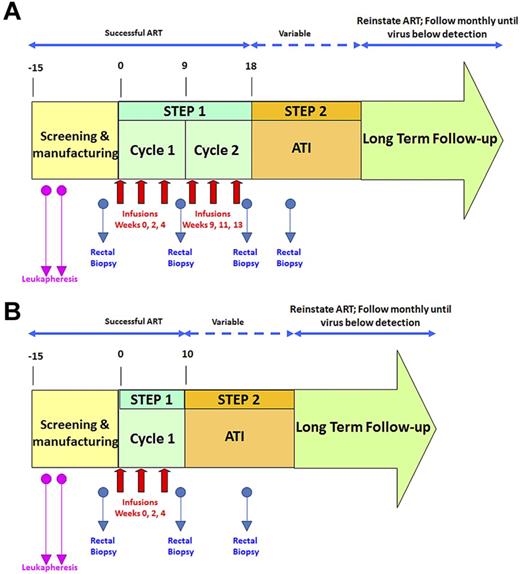

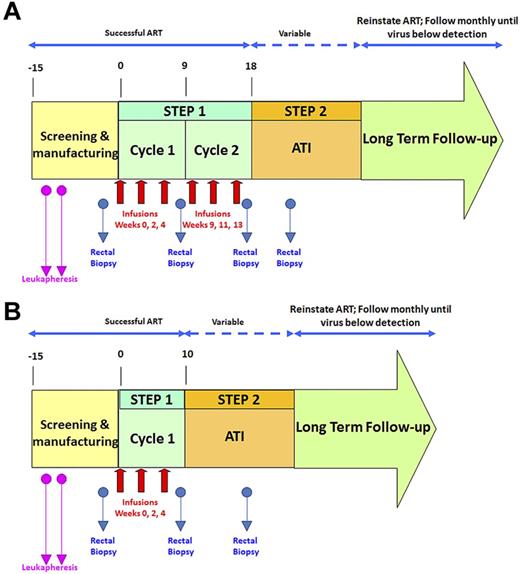

An overview of the study design is shown in Figure 1. To assess the effects of VRX496-T separately from ART, patients underwent an ATI and the effect on time to viral recrudescence, viral load set point, and viral sequence composition was assessed. Persistence of VRX496-T in the peripheral blood and in GALT was evaluated, and integration site analysis was used to assess possible vector-mediated genotoxicity.

Schematic of clinical trial design. Red arrows indicate infusions of 10 billion T cells each. Blue arrows indicate time points of rectal biopsies. The second leukapheresis (pink arrows) was taken to provide baseline samples and also to serve as a backup if the first manufacture run failed. After initial data indicated that the second cycle of infusions was not increasing VRX496-T persistence, it was removed for later patients. (A) Original study design. (B) Modified study design after removal of second infusion cycle .

Schematic of clinical trial design. Red arrows indicate infusions of 10 billion T cells each. Blue arrows indicate time points of rectal biopsies. The second leukapheresis (pink arrows) was taken to provide baseline samples and also to serve as a backup if the first manufacture run failed. After initial data indicated that the second cycle of infusions was not increasing VRX496-T persistence, it was removed for later patients. (A) Original study design. (B) Modified study design after removal of second infusion cycle .

Twenty-one patients were screened for this study: 17 were enrolled (Table 1) and 4 were screened out because of a detectable viral load at screening (n = 3) or failure to comply with study visits (n = 1). During step one, each patient received up to 2 treatment cycles of 3 infusions of 5 × 109 to 1 × 1010 autologous VRX496-transduced CD4 T cells at a target transduction range of 0.5-5 copies per cell. A total of 87 infusions were given to the 17 subjects. After the first 12 participants received 6 infusions, it was observed that the second cycle of infusion did not result in improved VRX496-T persistence and therefore the protocol was amended so that the last 5 participants received 3 infusions and cycle 2 of step 1 was discontinued (Figure 1).

No serious adverse events and no unexpected adverse events related to the study treatment occurred during a median of 5 years of follow-up (range, 3.5-6 years as of November 1, 2012). Three grade 4 adverse events were reported in individual patients. These were determined to be unrelated to the study and were the result of: (1) a preexisting condition (hypertriglyceridemia) occurring 8 months after infusion and in the absence of persisting cells, (2) hospitalization resulting from a fractured arm after an accidental fall, and (3) a high aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase in a patient with a known history of heavy alcohol consumption. All subjects who interrupted therapy and restarted ART regained an undetectable HIV RNA viral load. No vector-derived replication-competent lentivirus was detected and there were no safety concerns associated with multiple infusions (supplemental Section 2.2). The most frequent side effect was the characteristic odor of DMSO related to the cryopreservative in the cryopreserved cells. All participants are now in long-term follow-up ranging between 3.5 and 6 years after infusion. A range of 5 × 109 to 1 × 1010 cells per infusion was administered, and VRX496 copy numbers per cell ranged from 0.25-3.4.

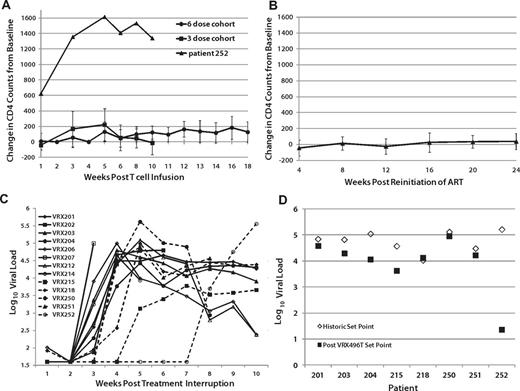

Changes in CD4 counts and viral load

Changes in CD4 T-cell counts since the time of infusion were computed for each patient. Significant within-subject increases of circulating CD4 cells after the infusion of the modified T cells was observed in the 6-dose cohort primarily between weeks 10 and 18 when ATI was initiated (P < .05 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test), but not in the 3-dose cohort, possibly because ATI was started at week 10 (Figure 2A and supplemental Table 3A-B). Patient 252, who received 3 doses, experienced an unexplained and unusually high increase in CD4 counts immediately after infusion, which was sustained after ATI (Figure 2A and supplemental Table 3A). Increases in CD4 counts after adoptive transfer of autologous lymphocytes in HIV patients have been reported previously,14 and were expected as a benefit in this study. Decreases in CD4 T-cell counts from baseline were significant during ATI compared with subjects who did not undergo ATI (P = .01 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test). CD4 counts of patients who underwent ATI but resumed ART returned to baseline (Figure 2B). There was no difference in CD4 changes from baseline in patients who either never underwent ATI or those who underwent ATI but resumed ART (P = .2).

Effects of VRX496-T on viral load and CD4 counts. (A) Average CD4 counts in patients after infusion and before ATI, with 252 plotted separately as an outlier. (B) CD4 counts in patients after resuming ARVafter ATI. No difference was observed between patients never on ATI and those who resumed ARV after ATI (P = .2345). (C) Virus recrudescence after ATI. (D) Viral set point analysis. Shown are the average of historic set point readings (♢) and the after ATI viral load readings averaged at week 10 and 14 after ATI (■). Patient 252 ultimately did have a measurable viral load, but it was undetectable at weeks 10 and 14 when the post-ATI set point was assessed.

Effects of VRX496-T on viral load and CD4 counts. (A) Average CD4 counts in patients after infusion and before ATI, with 252 plotted separately as an outlier. (B) CD4 counts in patients after resuming ARVafter ATI. No difference was observed between patients never on ATI and those who resumed ARV after ATI (P = .2345). (C) Virus recrudescence after ATI. (D) Viral set point analysis. Shown are the average of historic set point readings (♢) and the after ATI viral load readings averaged at week 10 and 14 after ATI (■). Patient 252 ultimately did have a measurable viral load, but it was undetectable at weeks 10 and 14 when the post-ATI set point was assessed.

Of the 17 patients treated with VRX496-T, 13 proceeded to ATI. As expected, the majority (11 of 13) of patients experienced recrudescence of virus between weeks 2 and 4 after ATI. However, patients 215 and 252 had a 4- and 14-week delay in the time to virus recrudescence, respectively (Figure 2C, supplemental Figure 6, and supplemental Table 1A-B). Patient 252 was a 52-year-old African-American woman who had been infected with HIV-1 for at least 6 years, with an HIV RNA viral load before the initiation of ART of 366 667 copies/mL and a nadir CD4 cell count of 302 cells/mm3. At entry, her CD4 cell count was 772 cells/μL, increasing to 2200 cells/μL after receiving 3 infusions of 1010 autologous VRX496-modified CD4 T cells. Initially, up to 12% of her circulating PBMCs carried the lentiviral insert, with no evidence of clonal expansion. Six weeks after the last infusion ART was discontinued. Her total bilirubin, which was elevated because of the atazanavir that she was receiving, decreased from 3 mg/mL to 0.6 mg/dL, confirming that she had discontinued her medication. Transduced CD4 cell frequency in the peripheral blood declined to 0.2% at day +76 after ATI. During a follow-up period of 104 days, the patient maintained an HIV RNA viral load below the limit of detection and a CD4 cell count greater than 1200 cells/μL. Afterward, her viremia returned, but remained below her baseline set point until 9 months after infusion (supplemental Table 1B).

Eight of the 13 patients who underwent ATI had historic viral load set points recorded before the initiation of ART, sometimes years before enrolling in this study. Of these 8, 6 had HIV RNA viral loads that were lower after ATI than their original set points (Figure 2D, Table 2, and supplemental Table 2). Using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to evaluate the changes in each patient, the overall decrease in viral load after infusion was nearly significant when using log-transformed data (P = .07812). These data suggest that the intervention may have had a direct although modest ART effect in vivo.

HIV sequence changes in the antisense target region

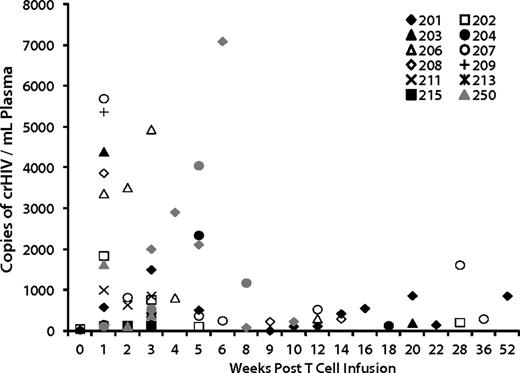

We evaluated genetic and immunologic factors to identify correlates with the effects on viral load. VRX496 was designed as a conditionally replicating viral vector in that it retains complete 5′ and 3′ LTR and other cis elements required for retroviral replication, so mobilization of the vector in the presence of wild-type HIV could influence therapeutic outcome.4,15 Conditional replication of VRX496 genomes was reported in our initial trial6 and occurs when HIV infects a transduced cell and then mobilizes the integrated vector genome, which interferes with HIV replication7 and theoretically could enhance control of HIV replication.16 Conditional replication was detected periodically through 1 year after infusion (Figure 3). Of the 8 patients evaluated after ATI, 5 of the 6 patients who had decreases in set point also had evidence of conditional replication, with patient 252 not showing conditional replication likely because no virus was replicating to support packaging of VRX496. One of the 2 “nonresponders,” patient 218, did not show signs of conditional replication (Figure 3). Evidence of conditional replication supports the hypothesis of viral evolution because it provides evidence for the existence of cells coinfected with HIV-1 and VRX496.

Conditional replication of VRX496 in vivo. Shown are all patients who had detectable conditionally replicating VRX496, which is measured by RT-PCR for vector RNA in patient plasma. Only time points at which VRX496 RNA was detected are shown. Closed symbols (black and gray) are patients who were evaluable for viral load changes.

Conditional replication of VRX496 in vivo. Shown are all patients who had detectable conditionally replicating VRX496, which is measured by RT-PCR for vector RNA in patient plasma. Only time points at which VRX496 RNA was detected are shown. Closed symbols (black and gray) are patients who were evaluable for viral load changes.

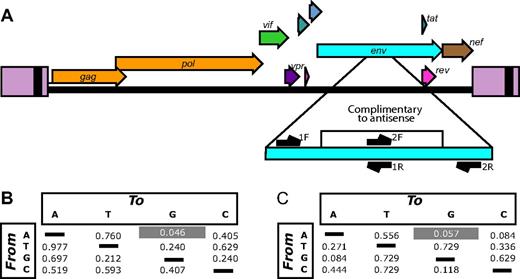

VRX496-mediated pressure on HIV env is known to lead to A → G substitutions or deletions in the antisense target region, yielding HIV mutants with genetic lesions likely to obstruct replication.4,9 Antisense-specific sequence variation was detected in an hNSG mouse model in which VRX496 modified human T cells and unmodified cells were infected with HIV.9 In this model, the presence of the antisense vector in cells was correlated with the accumulation of A → G base substitutions and deletions in replicating HIV-1 populations. Therefore, we sought to determine whether such patterns could be detected in circulating HIV from the subjects treated in the present study.

Plasma samples from the 8 patients evaluable after ATI were studied longitudinally from at least 2 time points ranging from approximately 4-42 weeks after ATI (supplemental Table 4). In some patients, the earliest specimen available was several weeks after the time of viral recrudescence. As a control, 9 patients from an unrelated treatment interruption trial were also studied (supplemental Table 5).13 The first time point was the earliest available after viral recrudescence. RNA was purified and amplified by RT-PCR with primers querying the antisense targeted region and adjacent nontarget regions that served as controls (Figure 4A). After pyrosequencing, approximately 220 000 sequences were obtained.

Viral evolution associated with VRX496 antisense. (A) The HIV genome showing the antisense-targeted region and the positions of amplicons used for deep-sequencing analysis. Note that each of the 2 amplicons query both antisense-targeted bases and adjacent nontarget bases. (B) P values comparing the enrichment of each type of base substitution in the antisense target region in VRX496-exposed patients with control ATI patients. For each patient, the proportion of reads with at least 5% of the indicated substitution (the starting base is shown to the left, the substituted base on top) was scored. Mean values of these proportions were compared between the VRX496-exposed and control ATI groups using the Mann-Whitney test. (C) P values comparing VRX496-exposed and ATI control patients using measurements derived from the difference in rates of each base substitution between the antisense-targeted region and the adjacent antisense-nontargeted region within each patient. P values were determined using the Mann-Whitney test.

Viral evolution associated with VRX496 antisense. (A) The HIV genome showing the antisense-targeted region and the positions of amplicons used for deep-sequencing analysis. Note that each of the 2 amplicons query both antisense-targeted bases and adjacent nontarget bases. (B) P values comparing the enrichment of each type of base substitution in the antisense target region in VRX496-exposed patients with control ATI patients. For each patient, the proportion of reads with at least 5% of the indicated substitution (the starting base is shown to the left, the substituted base on top) was scored. Mean values of these proportions were compared between the VRX496-exposed and control ATI groups using the Mann-Whitney test. (C) P values comparing VRX496-exposed and ATI control patients using measurements derived from the difference in rates of each base substitution between the antisense-targeted region and the adjacent antisense-nontargeted region within each patient. P values were determined using the Mann-Whitney test.

After quality filtering, consensus sequences were determined for each patient HIV-1 population for the first time point and base changes departing from the consensus tabulated (see supplemental Methods for details). Sequences were scored by whether they achieved 5% substitutions of each of the 12 types of base substitutions. Figure 4B compares the frequencies of such sequences for the VRX496-treated subjects and the control ATI subjects at the first time point. A → G transitions showed enrichment in the VRX496-treated subjects relative to controls (P = .046 by Mann-Whitney test). No other base substitution showed a significant difference. A second form of comparison took advantage of control regions flanking the VRX496-targeted region, allowing a differential to be scored for each type of base substitution between the targeted and nontargeted regions. The differentials for the VRX496-treated subjects and control ATI subjects were then compared (Figure 4C). A trend was seen toward greater differentials for A → G in the VRX496-treated subjects (P = .057 by Mann-Whitney test). A → G was also the most strongly affected substitution in this case. These differences were seen only in the initial time point analyzed after ATI and not at later time points, tracking with the temporal decline in the total proportion of gene-modified cells and enhanced replication of HIV-1 after ATI.

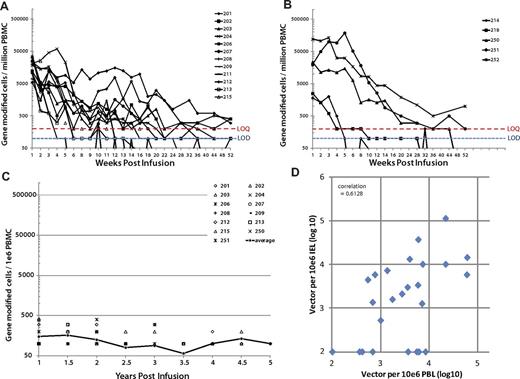

Persistence of gene-modified cells and gut mucosal trafficking

The frequency of gene-modified cells increased after the first 3 VRX496 gene-modified T-cell infusions, but the increases were transient and were not sustained during cycle 2 compared with cycle 1. There was variability in the level of persistence, with patients 251 and 252 exhibiting up to 10% or more PBMCs containing VRX496 and others, such as 214 and 218, with minimal persistence (Figure 5A-B and supplemental Table 6A-B). The half-life of VRX496-T was evaluated using an exponential decay model. There was no difference in half-life duration of VRX496-T between the 3- and 6-infusion cohorts by F test (P = .08), and the estimated combined half-life across all patients was 5.28 weeks (95% confidence interval, 4.07-7.53). Thirteen of the patients had sustained persistence of VRX496-T in the blood for up to 5 years (Figure 5C and supplemental Table 6A-B). Persistence did not stabilize or increase during ATI, indicating that there was no selection for VRX496-T during viremia. To investigate whether any VRX496-T cells were eliminated by an immune response targeted against cryptic open reading frames possibly present in the vector, we performed a series of flow cytometry–based assays on the cell product using serum and cells collected before and after the T-cell infusion in a subset of patients who either had good or poor persistence of VRX496-T. There were no detectable cellular or humoral responses to the cell product (supplemental Figures 4 and 5).

Persistence of VRX496-T in patients receiving 6 and 3 doses of cells in blood and gut. Individual patients are shown because of a high level of variability in persistence levels between patients. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the PCR assay was 200 copies (red dotted line) and the limit of detection was 100 copies (blue dotted line). Incidences where vector was detected below the LOQ but above the limit of detection are plotted at 100. Graphs show persistence in patients receiving 6 (A) and 3 (B) doses. Note that patient 214 was enrolled on the 6-dose protocol but only received 3 infusions because of a quality control test delay and so is represented in panel B. (C) Long-term persistence of VRX496-modified cells in patients with engraftment beyond 1 year. Average level in blood is indicated by the closed circles and black line, with individual data points indicated. Only patients with persisting cells at 1 year and beyond are shown. (D) Levels of VRX496 in mononuclear cells in the gut versus the peripheral blood. The correlation is highly significant at P = .000017 with an R2 of 0.667. Samples below the LOQ were defined as 10 for the visual purposes of this graph; changing the value of the number assigned to samples below the LOQ to 1 was evaluated and had no impact on the level of significance of the correlation.

Persistence of VRX496-T in patients receiving 6 and 3 doses of cells in blood and gut. Individual patients are shown because of a high level of variability in persistence levels between patients. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the PCR assay was 200 copies (red dotted line) and the limit of detection was 100 copies (blue dotted line). Incidences where vector was detected below the LOQ but above the limit of detection are plotted at 100. Graphs show persistence in patients receiving 6 (A) and 3 (B) doses. Note that patient 214 was enrolled on the 6-dose protocol but only received 3 infusions because of a quality control test delay and so is represented in panel B. (C) Long-term persistence of VRX496-modified cells in patients with engraftment beyond 1 year. Average level in blood is indicated by the closed circles and black line, with individual data points indicated. Only patients with persisting cells at 1 year and beyond are shown. (D) Levels of VRX496 in mononuclear cells in the gut versus the peripheral blood. The correlation is highly significant at P = .000017 with an R2 of 0.667. Samples below the LOQ were defined as 10 for the visual purposes of this graph; changing the value of the number assigned to samples below the LOQ to 1 was evaluated and had no impact on the level of significance of the correlation.

It is now widely recognized that the gastrointestinal tract is the dominant site of HIV replication.17 Only 2% of the total body T cells circulate in the peripheral blood, with the remainder found in lymphoid tissues such as the lymph nodes, tonsils, and gut mucosa. Rectal mucosal biopsies are preferred to lymph node or tonsillar biopsies because of patient tolerability, ability to acquire repeat samples, and fewer complications.18 Prior studies have evaluated trafficking of gene-marked cells to gut mucosae through bulk tissue analysis by PCR.19,20 Intraepithelial lymphocytes were isolated from rectal biopsies at baseline and post infusion before and after ATI,21 characterized for CD3/4/8 by flow cytometry, and analyzed for VRX496 by PCR. The percentage marking per CD4 T cell was calculated and compared with the levels in the periphery using a linear mixed (random) effects mode; negative values were evaluated as a constant or as a random number from 0 to the limit of detection.22 We found a significant correlation between VRX496-T in the GALT and persistence in the periphery (Figure 5D and supplemental Table 7). To our knowledge, this is the first report that quantitatively measures engraftment of gene-modified cells in the lymphoid compared with the peripheral blood compartments. These data indicate that gene marking in the peripheral blood is a good predictor of engraftment of gene-modified cells in the GALT.

Persistence of VRX496-T was not correlated with antiviral response (supplemental Table 6A-B). Furthermore, no increase in HIV-specific immune responses was observed in any patients by the CD107b degranulation assay (supplemental Table 10). Therefore, to date, no immune correlates of viral load changes have been identified.

Integration site analysis

To detect potential adverse effects of vector integration, we recovered more than 24 000 unique integration sites from longitudinal samples ranging from preinfusion up to 24 weeks after infusion in a select subset of patients chosen based on high level of gene-marked cells at these time points, and analyzed their abundance and genomic distribution (supplemental Table 8). For analysis, sites from all evaluated patients were pooled from preinfusion transduced cells or postinfusion cells. Integration sites from a Jurkat cell line infected in vitro were also included for comparison. Preinfusion, postinfusion, and Jurkat sites were all enriched in transcription units, with the level in Jurkat cells being slightly lower (P < .001; Figure 6A). Preinfusion integration sites were the most enriched in highly expressed genes, followed by Jurkat cells, with postinfusion sets being the least favored (Figure 6B). Similar trends were seen comparing the 3 sets with other genomic features associated with gene expression, such as regions high in the CpG island, gene density, and guanosine-cytosine content. We also assessed the frequency of vector sites near reported cancer-associated genes (Figure 6C). Postinfusion samples did not show statistically significant favoring of integration near cancer-associated genes in any of the patients. Furthermore, we did not find any evidence for enrichment of sites near cancer-associated genes at the latest time point examined (24 months afater infusion; data not shown). We did not recover any sites near or within genes associated with vector-induced oncogenesis observed in gene therapy trials targeting hematopoietic stem cells (eg, LMO2, CCND2, SPAG6/BMI1, and EVI1) in samples from patients after infusion. This is consistent with our earlier analysis of VRX496 viral integration sites in the first 5 participants in the phase 1 study.23 We conclude that there was no evidence of vector-induced clonal expansion in the participants of this study.

Integration site distributions from pre- and postinfusion time points in or near transcription units, highly expressed genes, and cancer-associated genes. (A) Proportion of integration sites found within genes as defined by the RefSeq database normalized to the proportion of matched random control sites within genes. The line at 1 marks the expected frequency for a random distribution; levels above 1 indicate associations enriched or favored compared with random; below 1, disfavored. Ex vivo indicates integration sites from patient cells transduced ex vivo, before infusion back into the patient; Jurkat, sites from Jurkat cells infected in vitro; postinfusion, sites isolated from CD4 T cells taken postinfusion (supplemental Table 8). Ex vivo and postinfusion datasets represent pooled sites from all 5 patients and time points. (B) Proportion of sites in highly expressed genes. Genes were binned into 7 equal bins of increasing gene expression as measured by the Affymetrix HU133 plus Version 2.0 gene chip array. Genomic intervals of 1 Mb were annotated for the numbers of highly expressed genes, with low expression on the left and high expression on the right, and then the proportions of integration sites in these bins were plotted. The line at 1 shows the expectation for a random distribution. “Ex vivo” and “postinfusion” represent pooled data from all 5 patients. (C) Proportion of sites near cancer-associated genes. The plot shows the proportion of sites < 50 kb from a RefSeq gene that were also < 50 kb from a cancer-associated gene. No patient showed significant enrichment of integration sites near cancer-associated genes (Fisher exact test, 1-sided in the direction of enrichment postinfusion found no pairs significantly different).

Integration site distributions from pre- and postinfusion time points in or near transcription units, highly expressed genes, and cancer-associated genes. (A) Proportion of integration sites found within genes as defined by the RefSeq database normalized to the proportion of matched random control sites within genes. The line at 1 marks the expected frequency for a random distribution; levels above 1 indicate associations enriched or favored compared with random; below 1, disfavored. Ex vivo indicates integration sites from patient cells transduced ex vivo, before infusion back into the patient; Jurkat, sites from Jurkat cells infected in vitro; postinfusion, sites isolated from CD4 T cells taken postinfusion (supplemental Table 8). Ex vivo and postinfusion datasets represent pooled sites from all 5 patients and time points. (B) Proportion of sites in highly expressed genes. Genes were binned into 7 equal bins of increasing gene expression as measured by the Affymetrix HU133 plus Version 2.0 gene chip array. Genomic intervals of 1 Mb were annotated for the numbers of highly expressed genes, with low expression on the left and high expression on the right, and then the proportions of integration sites in these bins were plotted. The line at 1 shows the expectation for a random distribution. “Ex vivo” and “postinfusion” represent pooled data from all 5 patients. (C) Proportion of sites near cancer-associated genes. The plot shows the proportion of sites < 50 kb from a RefSeq gene that were also < 50 kb from a cancer-associated gene. No patient showed significant enrichment of integration sites near cancer-associated genes (Fisher exact test, 1-sided in the direction of enrichment postinfusion found no pairs significantly different).

Discussion

This early-phase study used an adaptive design and was originally powered to detect changes in time to virus recrudescence; changes in viral load set point were performed as a secondary end point. The original planned sample size for the study was 18 patients but, of these, only 8 underwent ATI and had available historic viral load values before initiation of ART. Therefore, a limitation to this study is that it may not be sufficiently powered for the set point end point. Furthermore, several patients only had a single historic viral load set point for comparison. A conservative approach of including all available historic set points for patient 250 was used rather than selecting only the most recent values, which tend to increase over time in patients who are infected for a long period before initiating ART. With these caveats in mind, our data show that infusion of VRX496-T was associated with near significant decreases in viral load set point after ATI.

After these intriguing clinical findings and data from prior studies in vitro and in hNSG mice9 demonstrating direct antisense effect on virus evolution, in the present study, we further evaluated the effect of the VRX496 antisense on virus in these 8 patients. We found that A → G transitions were enriched in HIV sequences in subjects exposed to the antisense RNA, which is consistent with a model in which genetic pressure is exerted on the virus during infection of transduced CD4 T cells and parallels previous results in vitro and in hNSG mice.9 Control samples for this analysis were obtained from a separate ATI trial and were matched as best as possible; nevertheless, the effect on our results of differences in background ART, or in the exact time point after ATI, cannot be definitively excluded from our results. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of genetic pressure on HIV exerted by gene-modified cells in human subjects.

For the first time, we quantify herein the engraftment of vector-modified CD4 T cells in the GALT, and show that levels in peripheral blood are a predictor of engraftment in GALT. The data also show that 6 infusions did not improve engraftment over 3 infusions, and the majority of patients have long-term persistence of the gene-modified T cells. Finally, after up to 6 years of long-term follow-up for delayed adverse events, we report that there is no evidence of clonal selection of lentiviral vector–transduced T cells. In-depth analysis of integration sites did not provide evidence for selection of cells with integration events that confer a growth advantage, so we have shown by several measures that conditionally replicative lentiviral vectors are safe.

Pressure on a virus exerted by ART, even in the absence of full viral suppression, is recognized to produce a population of variants that can be less fit and therefore less pathogenic.24 Previous in vitro studies indicated that similar effects on fitness were observed for VRX496-T.4 In previous work with a mouse model, we documented evidence of antisense pressure on circulating virus in vivo.9 In the present study, we found evidence for modestly higher A → G transitions in patients receiving VRX496-T, although the same was not true for deletions. The A → G effect was only apparent for the first time point, which tracks with declining proportions for VRX496-T in patients over time. Once a virus breaks through, it is likely that any antisense effect would be progressively diluted because fewer viruses interact with dwindling numbers of modified cells, making antisense signatures more difficult to detect at later time points. The A → G effects were most evident when interpreted against the founder consensus generated from only those sequences obtained from the first time point analyzed after ATI. This is consistent with the expectation that antisense pressure would be discernible at the level of breakthrough virus rather than in later variants. The A → G signal observed in our clinical trial was less than in our prior animal model study, in which VRX496-modified cells comprised 4%-10% of all engrafted T cells and the input virus was homogenous. In the clinical trial, the levels of VRX496-T in the blood around the time of ATI was less than 1% in all patients and even lower (0.01%-0.20%) around the first time points after ATI, and the in vivo heterogeneity of HIV reduced the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting antisense-mediated changes. These considerations likely account for the lower rate of A → G substitutions observed in the clinical trial.

Our present study further demonstrates the safe use of lentiviral vectors in T cells. Lentiviral vectors may be safer than gammaretroviral vectors because of the lack of strong enhancer elements in the LTR,25 and although potential insertional mutagenesis has been observed in stem cells, T cells are known to be more resistant to transformation than stem cells.26 Conditional replication of VRX496 was observed for at least 1 year in the present study, whereas in our previous pilot study, this was observed for only 6 weeks.6 Long-term follow-up of the participants in this and our prior HIV-based lentiviral vector trials, combined with the extensive integration site analysis, continues to support safety of these conditionally replicating vectors.6,23 Long-term follow-up from our predecessor trial has now entered its eighth year and no delayed adverse events related to VRX496-T have occurred.6

Maintaining and improving CD4 T-cell function is a central goal in the management of persons infected with HIV. Clinical studies have shown that genetically modified CD4 T lymphocytes can survive for long periods in vivo in HIV-infected subjects.6,27,28 Genetically modified lymphocytes can repopulate subjects suffering from SCID when modified cells have a selective advantage over unmodified cells.29 A central aim of the present study was to increase the percentage of VRX496-T in patients by administering multiple infusions followed by selective outgrowth of cells during ATI. Unexpectedly, we found that additional infusions did not improve persistence, and that poor persistence did not result from antibody- or cell-mediated rejection of the cell product. A possible explanation is that there may have been competition of TCR-peptide MHC interactions and other trophic factors that govern the dominance of T-cell clones in vivo, which could self-limit the survival of large numbers of infused cells.30,31 This may contribute to the safety of T-cell therapy with integrating vectors.32,33

Unless repeat infusions are given, prolonged engraftment is required for HIV gene therapy to have durability. The half-life of VRX496 T cells was 5 weeks in the present trial, but we have demonstrated decade-long engraftment of T cells expressing the CD4-ζ chimeric antigen receptor in HIV patients, indicating that long-term engraftment is possible.34 The mechanism for the much longer (> 16-year) half-life of CD4-ζ chimeric antigen receptor T cells remains unclear, because we were unable to demonstrate an immune response directed against VRX496 T cells. VRX496-T did not selectively expand in the presence of viremia, confirming mathematical modeling16,35 and indicating that VRX496, as expected, does not protect transduced cells once they are infected. Alternative approaches may be needed, such as combination with a more potent genetic antiviral to drive selective outgrowth of cells during viremia1,36-38 or preinfusion conditioning regimens to promote homeostatic proliferation of the infused cells to enhance engraftment39 and facilitate durable efficacy.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shane Jensen for statistics discussions regarding viral evolution; Frances Male for assistance on the virus sequence evolution and integration site studies; Kyle Bittinger for help with de-noising pyrosequence reads for the study regarding viral evolution; Cathleen Afable and Kris Andre for vector production and release and for carrying out assays for vector persistence and expression in patient samples; Angelo Seda, Larisa Zifchak, and Joe Quinn for serving as the research nurses; Mark Sudell for data collection; Ro Kappes for regulatory support and guidance; Michael Lederman, Paul Johnson, Luis Montaner, Guido Silvestri, and David Weiner for helpful discussions as advisors; Boro Dropulic for vector design and contributions to the field; and Frosso Volgaropoulou and Sandra Bridges for constructive input as program officers.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (program project grant U19 AI066290); the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants AI48398 and U01AI065279 to L.J.M.); James Hoxie and the Penn Center for AIDS Research (P30 AIO45008); and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (fellowship to T.B.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.T. designed the study and acted as the lead primary investigator; D.S. acted as the co–primary investigator; G.B.-S. was responsible for the management and execution of all aspects of the clinical study and analysis and wrote the manuscript; R.M. designed and carried out the viral evolution; T.B. performed the integration site analysis; T.R. contributed to the clinical design and analysis; L.H. contributed to the scientific design of the vector and analysis of vector persistence and expression in patient samples; M.K. performed the immune correlative studies; E.P. and L.J.M. contributed the control patient samples for the virus-sequencing analysis; D.S. managed all patient samples and performed intraepithelial lymphocyte isolation and flow analysis; F.S. performed analysis for HIV and vector on intraepithelial lymphocyte samples; A.L.B., Z.Z., and J.C. performed the cell-manufacturing validation and product manufacture and release; V.S. performed vector production and release and carried out assays for vector persistence and expression in patient samples; E.V. maintained Good Clinical Practices and all regulatory aspects of the study; A.M. served as the study monitor and provided audited data for the manuscript; W.-T.H. performed all statistical analyses; F.A. and J.Z. performed the rectal biopsies; J.B. directed the management of patient sample handling and intraepithelial lymphocyte isolation procedures; R.G.C. led the molecular analyses on the intraepithelial lymphocytes; F.D.B. conceived and directed the virus-sequence analysis and integration site studies; B.L.L. developed the cell-manufacturing process and contributed to the study design; and C.H.J. conceived of the clinical study, assembled and managed the clinical and research teams, functioned as regulatory sponsor, and coordinated the data analysis and final manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.S., T.R., and L.H. are/were employees of ViRxSYS Corporation. C.H.J. and B.L.L. have intellectual property rights to some of the cell-culture technologies described in the manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Carl H. June, Smilow Center for Translational Research, 3400 Civic Center Blvd, Bldg 421, 8th FL, Rm 123, Philadelphia, PA 19104-5156; e-mail: cjune@exchange.upenn.edu.

References

Author notes

P.T., D.S., and G.B.-S. contributed equally to this work.