Key Points

GATA3 is elevated in E2A−/− DN2 cells.

GATA3 contributes to arrested T-cell development from E2A−/− DN2 cells.

Abstract

The E2A transcription factors promote the development of thymus-seeding cells, but it remains unknown whether these proteins play a role in T lymphocyte lineage specification or commitment. Here, we showed that E2A proteins were required to promote T-lymphocyte commitment from DN2 thymocytes and to extinguish their potential for alternative fates. E2A proteins functioned in DN2 cells to limit expression of Gata3, which encodes an essential T-lymphocyte transcription factor whose ectopic expression can arrest T-cell differentiation. Genetic, or small interfering RNA-mediated, reduction of Gata3 rescued T-cell differentiation in the absence of E2A and restricted the development of alternative lineages by limiting the expanded self-renewal potential in E2A−/− DN2 cells. Our data support a novel paradigm in lymphocyte lineage commitment in which the E2A proteins are necessary to limit the expression of an essential lineage specification and commitment factor to restrain self-renewal and to prevent an arrest in differentiation.

Introduction

T-lymphocyte specification and commitment are associated with dynamic alterations in the transcriptome which are regulated by the complement of expressed and functional transcription factors.1 Although numerous transcription factors are essential for T-cell development, the transcriptional networks in which they operate and their essential targets are not well understood.

One critical regulator of T-lymphocyte specification is NOTCH1, a transmembrane receptor and transcriptional coactivator. The intracellular domain of NOTCH1 (ICN1), which translocates to the nucleus and regulates gene expression,2 activates multiple transcription factors in thymocytes, including Notch1, Hes1, Tcf7, and Gata3. TCF7 (TCF1) induces a subset of NOTCH1 target genes, including Gata3, and limits alternative fates from multipotent progenitors (MPPs) in vitro in the absence of NOTCH1,3 although its role as a T-cell commitment factor in vivo is disputed.4 Although GATA3 is essential for T-cell specification, high concentrations of GATA3 block T-lymphocyte differentiation in vitro at the DN2 stage and prevent the development of T lymphocyte–committed DN3 cells.5 Moreover, overproduction of GATA3 reprograms DN2 cells into mast cells, but this reprogramming is restrained by NOTCH1.6 Thus, GATA3 expression should be regulated to promote T-cell specification and commitment while not achieving sufficient expression to block T-cell development or divert cells to an alternative fate. However, it remains controversial whether GATA3 can achieve the concentration necessary to block T-cell development under physiologic conditions and whether mechanisms exist to limit Gata3 during T-cell development.

The E2A transcription factors are required for proper T lymphopoiesis but, unlike NOTCH1 and GATA3, they are essential at earlier stages of lymphopoiesis.7 Mice lacking E2A have reduced numbers of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors and common lymphoid progenitors; therefore, they should have fewer thymus-seeding cells.7 In addition, E2A−/− lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors fail to express CCR9, a chemokine receptor involved in thymic homing,8 and have reduced expression of Notch1.9 Thus, E2A−/− bone marrow cells should be compromised in their ability to seed the thymus. In vitro, E2A−/− hematopoietic progenitors fail to differentiate into T lymphocytes unless they are forced to express ICN1, suggesting that their reduced expression of Notch1 prevents T-cell differentiation.10 Nonetheless, previous studies showed that the earliest T-cell population (DN1) is present in the thymus of E2A−/− mice, although differentiation appears to be partially arrested just before the DN2 stage (DN1.5).11,12 These older studies used staining strategies that are now known to be insufficient to identify the earliest thymic progenitors (ETPs) within the heterogeneous DN1 compartment.13,14 Therefore, a requirement for E2A at the earliest stages of T lymphocyte lineage specification or commitment in the thymus has not been demonstrated.

Here, we demonstrated that E2A was required for the efficient differentiation of DN2 cells into T lymphocyte lineage-restricted DN3 cells. We found that E2A played a critical role in limiting Gata3 expression specifically in DN2 cells. With the use of both Gata3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and heterozygous deletion of Gata3, we demonstrated that GATA3 was responsible for the arrested differentiation of E2A−/− DN2 cells. Moreover, we demonstrated that the heightened expression of GATA3 caused an aberrant proliferation of DN2 and DN3 thymocytes in vivo. In the absence of E2A, DN2 cells have an increased propensity to adopt non–T-cell fates that was not influenced by Gata3 dose. However, reducing Gata3 resulted in an overall reduction in the number of non–T-cell progenitors in vivo. We propose a model in which the overproduction of GATA3 extends the self-renewal capacity of DN2 cells and inhibits T lineage restriction, whereas E2A deficiency, independent of the overproduction of GATA3, allows DN2 cells to access alternative fates. Thus, T-lymphocyte commitment requires passage through a checkpoint in DN2 cells in which positive and negative inputs to Gata3 must be balanced to allow further differentiation.

Methods

Mice and genotyping

This work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Chicago under protocol ACUP 71 119. Mice were housed at the University of Chicago Animal Resource Center. Genotyping for the E2A and Gata3 alleles was performed as described.15,16 Tie2Cre transgenic mice were genotyped by PCR. Adult mice were analyzed at 6-8 weeks of age.

Flow cytometry/cell sorting

The antibody clones and fluorochrome combinations used in this study are available on request. All antibodies were purchased from eBiosciences or BD Biosciences.

The lineage cocktail for adult thymocytes included CD3ϵ, CD8α, TCRβ, TCRγδ, NK1.1, CD11c, Ter-119, CD11b, Gr1, B220, and CD19 and for fetal liver (FL) included Ter119 and Gr1. For in vitro culture of retrovirus-transduced MPPs, cells were sorted 48 hours after transduction as GR1−Ter119−CD117+CD27+GFP+ cells. Cells were examined on a FACSCanto or FACSAria and analyzed with FlowJo Version 9.5 (TreeStar). For sorting, thymocytes were depleted of Lin+ cells on a magnetic column (Miltenyi Biotec) before staining for sorting.

In vivo BrdU incorporation

Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of BrdU per 6 g of body weight (BD Biosciences) 24 hours and 12 hours before the analysis. BrdU staining was performed with the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences).

In vitro culture and retroviral transduction

OP9-DL1 stromal cells were maintained in OPTI-MEM and plated 1 day before use to achieve a near confluent monolayer of cells. Cells were cultured on OP9-DL1 cells in the presence of 5 ng/mL Flt3 ligand, IL-7, and CD117 ligand. The retroviral vectors and transduction procedures were described previously.17

RNA analysis

RNA was extracted with the use of the RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed with SuperscriptIII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with the use of random hexamers. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed in triplicate with the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and detected by the MyiQ Single color Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Expression levels were calculated for each gene relative to Hprt with the use of the ΔCT method. The primers used in this study are available by request. Microarray procedures (GEO accession no. GSE43224) were as described previously.9

Results

E2A is required for the proper generation of T-cell progenitors

A rigorous analysis of E2A−/− thymocytes by flow cytometry showed that E2A was required for normal ETP, DN2, and DN3 thymocyte numbers in vivo (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The previously defined “DN1.5” population identified among E2A−/− Lin− thymocytes11,12 was not detected when ETPs/DN2 cells were identified with CD117. However, a Lin−CD25loCD117lo population was present that included CD44lo cells that lacked IL7Rα and CD122, and CD44hi cells that expressed IL7Rα but not CD122. In vitro culture of Lin−CD25loCD117lo subsets showed that they included progenitors of non–T-cell lineages, including natural killer (NK) cells.

On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that E2A was necessary to bias ETPs/DN2s toward the T-lymphocyte fate. To test this hypothesis, we compared the ability of cells from E2A+/+, E2A+/−, and E2A−/− mice to generate Lin−CD44−CD25+ cells (DN3-like cells) in vitro. When cultured under T cell–supportive conditions the progeny of wild-type ETPs and DN2s were predominantly DN3-like, and only a few cells expressed the NK-cell marker NK1.1 (Figure 1A-B). Further, wild-type (WT) ETPs and DN2s underwent an approximate 10 000-fold increase in numbers (not shown). In contrast, E2A−/− ETPs and DN2s expanded poorly and generated few DN3-like cells (Figure 1A,C). Most E2A−/− cells remained CD44lo/+CD25lo, and a substantial portion of these cells expressed NK1.1 (Figure 1A-B). E2A+/− DN2s, and to a lesser degree ETPs, also generated fewer DN3-like cells, indicating a dose-dependent requirement for E2A (Figure 1A-C).

A dose-dependent requirement for E2A in the generation of DN3 cells from ETPs and DN2 cells. FACS-purified ETPs (250 cells/well) and DN2 cells (500 cells/well) from adult E2A+/+, E2A+/−, and E2A−/− thymuses were cultured on OP9-DL1 for 10 days, and CD11b−CD8− cells were analyzed for expression of (A) CD44 and CD25 or (B) NK1.1 and CD25. (C) Relative number of DN3 cells generated from E2A+/+, E2A+/−, or E2A−/− ETPs and DN2s on day 10 of culture. Data represent the average of 5 independent experiments; *P < .001. (D) Single DN2 cells from E2A+/+ and E2A−/− mice were sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate that contained OP9-DL1 and cultured for 10 days. Individual colonies were analyzed for expression of CD44 and CD25 on CD11b−CD8− cells. Percentage of colonies that generated only DN3 cells (black) or a mixture of DN3 cells and other cell types (gray) or no DN3 cells (white) is shown. Numbers are combined from 3 independent experiments with 3 plates per sample. (E) Representative FACS plots of colonies generated from single E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells.

A dose-dependent requirement for E2A in the generation of DN3 cells from ETPs and DN2 cells. FACS-purified ETPs (250 cells/well) and DN2 cells (500 cells/well) from adult E2A+/+, E2A+/−, and E2A−/− thymuses were cultured on OP9-DL1 for 10 days, and CD11b−CD8− cells were analyzed for expression of (A) CD44 and CD25 or (B) NK1.1 and CD25. (C) Relative number of DN3 cells generated from E2A+/+, E2A+/−, or E2A−/− ETPs and DN2s on day 10 of culture. Data represent the average of 5 independent experiments; *P < .001. (D) Single DN2 cells from E2A+/+ and E2A−/− mice were sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate that contained OP9-DL1 and cultured for 10 days. Individual colonies were analyzed for expression of CD44 and CD25 on CD11b−CD8− cells. Percentage of colonies that generated only DN3 cells (black) or a mixture of DN3 cells and other cell types (gray) or no DN3 cells (white) is shown. Numbers are combined from 3 independent experiments with 3 plates per sample. (E) Representative FACS plots of colonies generated from single E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells.

We next tested the frequency of DN2s with T-lineage potential with the use of single-cell analysis. A reduced frequency of E2A−/− DN2 cells gave rise to DN3-like cells compared with WT DN2s, although the cloning efficiencies were identical (Figure 1D). Further, single E2A−/− DN2s produced more non–T cells (mostly NK1.1+) than DN3-like cells, indicating that in the absence of E2A these cells were not efficient T-lymphocyte progenitors (Figure 1D-E). Taken together, our data indicated that E2A−/− and E2A+/− ETPs and DN2s had a diminished capacity to differentiate into committed T lymphocytes but had increased potential for alternative lineages such as NK cells. Our findings are consistent with a previous study showing that deletion of E2A and Heb in early T-lineage cells arrests differentiation at the DN2 stage in vitro.18

Decreased T cell– and increased NK cell–associated transcripts in E2A−/− DN2 cells

A plausible explanation for the reduced T-cell potential of E2A−/− DN2 cells is that they expressed less Notch1.10 qPCR analysis of E2A−/− DN thymocytes showed that Notch1 mRNA was decreased by only 50% compared with WT (Figure 2A). Given that Notch1+/− mice can generate DN3-like cells19 and that E2A−/− thymocytes express the Notch target gene Deltex1 (Figure 2A), we concluded that reduced Notch signaling did not explain the decreased ability of E2A−/− DN2s to generate DN3-like cells.

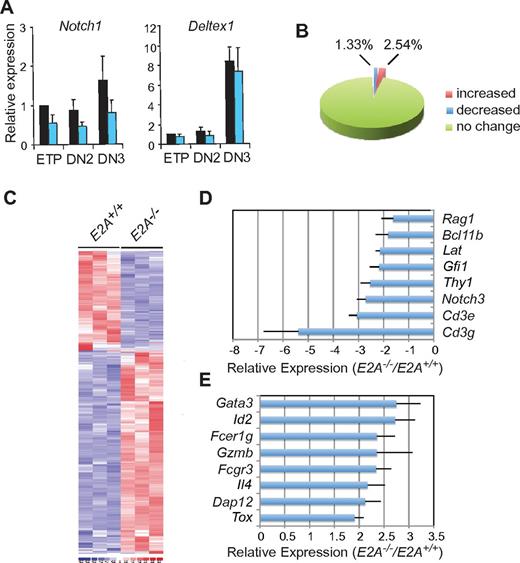

E2A−/− DN2 thymocytes have altered expression of T lymphocyte– and NK cell–associated genes. (A) qPCR analysis of Notch1 and Deltex1 mRNA in E2A+/+ and E2A−/− ETPs and DN2 and DN3 thymocytes. Expression was normalized to Hprt and shown relative to E2A+/+ ETPs. Data are combined from 3 experiments with triplicate measurements. (B) Pie graph shows the percentage of genes that were differentially expressed between E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells as determined by microarray analysis. (C) Heat maps show differential gene expression in E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells. (D) Relative change in expression for a selected set of genes that decreased or (E) increased in E2A−/− compared with E2A+/+ DN2 cells. Error bars represent the SE from triplicate microarray experiments.

E2A−/− DN2 thymocytes have altered expression of T lymphocyte– and NK cell–associated genes. (A) qPCR analysis of Notch1 and Deltex1 mRNA in E2A+/+ and E2A−/− ETPs and DN2 and DN3 thymocytes. Expression was normalized to Hprt and shown relative to E2A+/+ ETPs. Data are combined from 3 experiments with triplicate measurements. (B) Pie graph shows the percentage of genes that were differentially expressed between E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells as determined by microarray analysis. (C) Heat maps show differential gene expression in E2A+/+ and E2A−/− DN2 cells. (D) Relative change in expression for a selected set of genes that decreased or (E) increased in E2A−/− compared with E2A+/+ DN2 cells. Error bars represent the SE from triplicate microarray experiments.

To gain insight into the mechanism underlying the loss of T-cell potential in E2A−/− DN2s, we performed a global analysis of gene expression. Remarkably, only 5.87% of the total DN2 cell transcriptome was altered by the loss of E2A, and most of the differentially expressed genes were increased in E2A−/− compared with E2A+/+ DN2 cells (Figure 2B-C). Multiple T cell–associated genes were decreased in E2A−/− DN2s, whereas NK cell-associated genes were increased (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Table 1). The altered expression of some of these genes may be a direct consequence of the loss of E2A (eg, Gfi1 and Cd3e).20 However, some genes may be differentially expressed because E2A−/− DN2 cells initiated differentiation toward alternative cell fates. Three genes were of particular interest, Bcl11b, Gfi1, and Gata3 (Figure 2D-E). Preliminary screens showed that Bcl11b expression was not affected by E2A deficiency in MPPs cultured under T-cell conditions. Moreover, ectopic expression of BCL11b did not rescue T-cell differentiation from E2A−/− MPPs in vitro (not shown). Gfi1 produces the transcriptional repressor GFI1 that is highly related to GFI1b, and both proteins were reported to be differentially expressed in E2A−/− T-cell lymphomas, and they repress Gata3.17,21 However, although ectopic expression of GFI1 or GFI1b promoted differentiation of E2A−/− MPPs to the DN2 stage in vitro, DN3 cells failed to develop, and GFI1-deficiency, unlike E2A-deficiency, did not compromise T-cell differentiation from MPPs in vitro (supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, we focused on GATA3 as the probable mediator of arrested T-cell development in E2A−/− mice.6

Increased expression of Gata3 in E2A−/− DN2 thymocytes

To confirm the differential expression of Gata3, we performed qPCR analysis on highly purified Lin− thymocytes from E2A+/+, E2A+/−, and E2A−/− mice. Gata3 transcripts were increased selectively in the DN2s, but not in ETPs or DN3 cells, of E2A+/− or E2A−/− mice (Figure 3A). The elevated Gata3 mRNA was not a consequence of altered Gata3 promoter usage because most mRNA initiated at the Gata3-1b promoter, as is seen in WT thymocytes (data not shown).22 Moreover, in E2A−/− MPPs cultured in vitro, Gata3 mRNA remained Notch-signaling dependent and increased progressively between days 4 and 8 (Figure 3B). GATA3 protein was elevated in E2A−/− DN2s and DN4s, and at varying amounts in DN3 thymocytes as well as in E2A−/− MPPs cultured in vitro for 10 days (Figure 3C-D). However, E2A−/− NK1.1+ cells did not express high levels of GATA3, indicating that deregulation of GATA3 was restricted to cells with T-cell potential. Taken together, our data indicate that E2A was required to limit Gata3 during commitment to the T-cell fate.

Elevated expression of Gata3 in E2A−/− DN2 cells in vivo and in vitro. (A) qPCR analysis shows Gata3 mRNA in ETPs, DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells from E2A+/+ (light blue), E2A+/− (medium blue), and E2A−/− (dark blue) mice. One of 4 representative experiments is shown with the SE from triplicate reactions. (B) qPCR analysis for Gata3 mRNA in E2A+/+ (light shade) or E2A−/− (dark shade) FL MPPs cultured on OP9 (green) or OP9-DL1 (blue) with Flt3L and IL-7 for 4, 6, or 8 days. One of 2 experiments is shown with error bars from triplicate measurements. (C) FACS analysis shows expression of GATA3 in ETPs and DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells from E2A+/+ (blue) and E2A−/− (red) mice or (D) DN1, DN2, DN3, or NK1.1+ cells from in E2A+/+ (blue), E2A+/− (green), and E2A−/− (red) in FL MPPs after 10 days of culture. Negative control staining is shown in gray. One of at least 3 experiments is shown.

Elevated expression of Gata3 in E2A−/− DN2 cells in vivo and in vitro. (A) qPCR analysis shows Gata3 mRNA in ETPs, DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells from E2A+/+ (light blue), E2A+/− (medium blue), and E2A−/− (dark blue) mice. One of 4 representative experiments is shown with the SE from triplicate reactions. (B) qPCR analysis for Gata3 mRNA in E2A+/+ (light shade) or E2A−/− (dark shade) FL MPPs cultured on OP9 (green) or OP9-DL1 (blue) with Flt3L and IL-7 for 4, 6, or 8 days. One of 2 experiments is shown with error bars from triplicate measurements. (C) FACS analysis shows expression of GATA3 in ETPs and DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells from E2A+/+ (blue) and E2A−/− (red) mice or (D) DN1, DN2, DN3, or NK1.1+ cells from in E2A+/+ (blue), E2A+/− (green), and E2A−/− (red) in FL MPPs after 10 days of culture. Negative control staining is shown in gray. One of at least 3 experiments is shown.

GATA3 overproduction prevents T-cell development from E2A−/− MPPs

We hypothesized that the dysregulation of Gata3 in E2A+/− and E2A−/− DN2 cells underlies their reduced DN3 cell potential. If this were the case, then lowering Gata3 expression should relieve E2A−/− cells from this developmental block. To test this hypothesis, we transduced E2A+/+ and E2A−/− MPPs with a retrovirus that produced Gata3 siRNA17,23 and assessed the ability of these cells to differentiate into DN3-like cells. When expressed in WT MPPs, the Gata3 siRNA induced a dose-dependent arrest at the DN2 stage (supplemental Figure 3; Figure 4A-B). In contrast, when Gata3 siRNA was expressed in E2A−/− MPPs, CD25+ cells developed and DN3-like cells were evident, whereas the control retrovirus failed to promote the development of these cells (supplemental Figure 3; Figure 4A-C). E2A−/− DN3 stage cells were enriched in the GFPlow population, whereas GFPhigh cells were arrested at the DN2 stage, indicating that low expression of Gata3 siRNA facilitates differentiation of E2A−/− MPPs to the DN3 stage, whereas high expression of Gata3 siRNA inhibits T-cell differentiation. The DN1 and CD25+ cells in E2A−/−Gata3 siRNA-expressing cultures had less Gata3 and Id2 mRNA compared with E2A−/− DN1 or CD25+ cells that expressed the control retrovirus (Figure 4D). These cells also expressed the T cell–associated genes Ptcra and Gfi1, indicating that they were specified to the T-cell fate (Figure 4D). Moreover, DN3-like cells in E2A−/−Gata3 siRNA-expressing cultures expressed Notch1 and Rag1 mRNA, indicating that they are T-lineage cells (supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, Gata3 siRNA was sufficient to allow some E2A−/− MPPs to reach a DN3-like stage.

Gata3 siRNA restores DN3-like cell development from E2A−/− FL MPPs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of E2A+/+ or E2A−/− FL MPPs transduced with control retrovirus or Gata3 siRNA retrovirus and cultured on OP9-DL1 in T cell–supportive conditions. GFP+ cells were enriched by cell sorting 48 hours after transduction and cultured for a further 12 days. (A) GFP versus side scatter (SSC) with gated regions indicate GFPneg, GFPlow, and GFPhigh populations. (B) CD44 and CD25 expression on GFPneg, GFPlow, and GFPhigh cells. One of 4 representative experiments is shown. (C) Average + SE of the percentage of cells expressing CD25 in all experiments. (D) qPCR analysis for Gata3, Id2, Ptcra, and Gfi1 mRNA in DN1-like and CD25+ cells isolated from E2A+/+ or E2A−/− cells transduced with control retrovirus (C) or with Gata3 siRNA (G). NA indicates not available. One of 2 similar experiments is shown. Bars represent the average + SE for the triplicate measurements in the experiment.

Gata3 siRNA restores DN3-like cell development from E2A−/− FL MPPs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of E2A+/+ or E2A−/− FL MPPs transduced with control retrovirus or Gata3 siRNA retrovirus and cultured on OP9-DL1 in T cell–supportive conditions. GFP+ cells were enriched by cell sorting 48 hours after transduction and cultured for a further 12 days. (A) GFP versus side scatter (SSC) with gated regions indicate GFPneg, GFPlow, and GFPhigh populations. (B) CD44 and CD25 expression on GFPneg, GFPlow, and GFPhigh cells. One of 4 representative experiments is shown. (C) Average + SE of the percentage of cells expressing CD25 in all experiments. (D) qPCR analysis for Gata3, Id2, Ptcra, and Gfi1 mRNA in DN1-like and CD25+ cells isolated from E2A+/+ or E2A−/− cells transduced with control retrovirus (C) or with Gata3 siRNA (G). NA indicates not available. One of 2 similar experiments is shown. Bars represent the average + SE for the triplicate measurements in the experiment.

Our data indicated that in the absence of E2A excess GATA3 caused a block in T-cell differentiation. However, the Gata3 siRNA was efficient at reducing Gata3 mRNA and reduced the total number of cells generated from WT and E2A−/− MPPs under T-cell conditions. To confirm that the excess GATA3 was responsible for this differentiation block, we generated mice deficient in E2A and heterozygous for a mutated allele of Gata3 in hematopoietic cells (Gata3+/Δ).24 We reasoned that this decrease in Gata3 may be sufficient to at least partially rescue the E2A−/− DN2 stage arrest. We first examined the effect of the Gata3+/Δ genotype on E2A−/− MPPs cultured in vitro. Remarkably, although few E2A−/−Gata3fl/+ MPPs acquired a DN3-like phenotype, as many as 15% of the cells derived from E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ MPPs were DN3-like on day 10 of culture (Figure 5A-B). As predicted, Gata3 mRNA was decreased by approximately 50% in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ cells compared with E2A−/− DN2-like cells (Figure 5C). Further, the E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN3-like cells underwent T cell–lineage specification as indicated by the increased expression of Notch1 and Rag1 mRNA (Figure 5D). These data indicated that inactivation of 1 Gata3 allele was sufficient to augment T cell–lineage commitment from E2A−/− MPPs during in vitro culture.

Heterozygous deletion of Gata3 restores DN3-like cell development from E2A−/− FL MPPs. (A) FACS analysis for CD44 and CD25 on the progeny of Lin− FL cells from control (including WT, Cre+, or Gata3+/fl), E2A−/−, or E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ embyros after culture on OP9-DL1 for 12 days. Data are representative from at least 3 experiments. (B) Average + SE derived from 6 mice of each genotype. (C) qPCR analysis for Gata3 or (D) Notch1 and Rag1 mRNA isolated from sorted DN1-like (white), DN2-like (gray), or DN3-like (black) cells isolated from the cultures shown in panel A. Expression is shown relative to WT DN1 cells. NA indicates not available. Data are from 1 of 2 similar experiments.

Heterozygous deletion of Gata3 restores DN3-like cell development from E2A−/− FL MPPs. (A) FACS analysis for CD44 and CD25 on the progeny of Lin− FL cells from control (including WT, Cre+, or Gata3+/fl), E2A−/−, or E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ embyros after culture on OP9-DL1 for 12 days. Data are representative from at least 3 experiments. (B) Average + SE derived from 6 mice of each genotype. (C) qPCR analysis for Gata3 or (D) Notch1 and Rag1 mRNA isolated from sorted DN1-like (white), DN2-like (gray), or DN3-like (black) cells isolated from the cultures shown in panel A. Expression is shown relative to WT DN1 cells. NA indicates not available. Data are from 1 of 2 similar experiments.

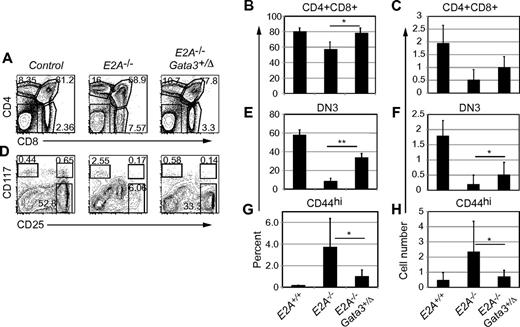

GATA3 overproduction contributes to the arrested T-cell development in E2A−/− mice

We next analyzed T-cell development in the thymus of E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice. Thymocyte populations in Gata3+/Δ mice were indistinguishable from WT, and there was no selection against the deleted allele (supplemental Figure 4). In accordance with previous reports,11,25 E2A−/− mice had a decreased percentage of double-positive (DP) thymocytes and an increased percentage of single-positive (SP) cells (Figure 6A-B). In contrast, the percentage of DP and SP cells among E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ thymocytes was indistinguishable from that of WT mice (Figure 6A-B). The number of DP thymocytes was only slightly increased by heterozygous deletion of Gata3, suggesting that GATA3 influenced differentiation but did not augment thymocyte expansion in the absence of E2A (Figure 6C). As expected, the number of ETP and DN2 cells in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice was similar to that in E2A−/− mice (data not shown). However, E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice had an increased frequency and number of DN3 cells compared with E2A−/− mice (Figure 6D-F). More dramatically, the frequency and number of Lin−CD117lo/−CD25lo (and CD44hi, not shown) cells in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice was lower than in E2A−/− mice, indicating that the reduced expression of Gata3 prevented the development of these cells while simultaneously augmenting DN3 cell differentiation in E2A−/− mice (Figure 6G-H). Given that Lin− numbers were decreased in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice compared with E2A−/− mice (data not shown), the increased number of DP and DN3 cells was striking, and the increased frequency of these populations is probably a better measure of differentiation potential than number compared with E2A−/− mice. The restoration of DP, SP, and DN3 cell frequencies and the partial rescue of DN3 cell numbers combined with the decreased frequency and number of Lin−CD117lo/−CD44hiCD25lo NK cell progenitors in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice supports the hypothesis that elevated expression of Gata3 in E2A−/− DN2 and/or DN4 cells perturbs T-cell development in vivo.

Heterozygous deletion of Gata3 partially restores T-cell development in E2A−/− mice. (A) FACS analysis for CD4 and CD8 in the thymus of E2A+/+, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice. The frequency of DP and SP subsets is shown. One representative of more than 10 experiments is shown. (B) Average + SD of the percentage or (C) total number of DP cells in control (including E2A+/+, Cre+, or Gata3+/fl) mice, E2A−/− mice, or E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice. *P < .05. (D) FACS analysis for CD117 and CD25 on Lin− thymocytes from the same mice as in panel A. The frequency of ETPs and DN2 and DN3 cells is shown in the gated regions. (E) Average + SD of the percentage or (F) total number of DN3 cells in mice of the indicated genotype. A minimum of 10 mice of each genotype were analyzed; **P < .01. (G) Average + SD of the percentage or (H) total number of Lin-CD117lo/−CD44hiCD25lo thymocytes in mice of the indicated genotype. A minimum of 10 mice of each genotype was analyzed.

Heterozygous deletion of Gata3 partially restores T-cell development in E2A−/− mice. (A) FACS analysis for CD4 and CD8 in the thymus of E2A+/+, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice. The frequency of DP and SP subsets is shown. One representative of more than 10 experiments is shown. (B) Average + SD of the percentage or (C) total number of DP cells in control (including E2A+/+, Cre+, or Gata3+/fl) mice, E2A−/− mice, or E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice. *P < .05. (D) FACS analysis for CD117 and CD25 on Lin− thymocytes from the same mice as in panel A. The frequency of ETPs and DN2 and DN3 cells is shown in the gated regions. (E) Average + SD of the percentage or (F) total number of DN3 cells in mice of the indicated genotype. A minimum of 10 mice of each genotype were analyzed; **P < .01. (G) Average + SD of the percentage or (H) total number of Lin-CD117lo/−CD44hiCD25lo thymocytes in mice of the indicated genotype. A minimum of 10 mice of each genotype was analyzed.

Overproduction of GATA3 compromises the DN3 cell potential of E2A−/− DN2 cells

One plausible explanation for the increased number of DN3 thymocytes in E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice is that these cells proliferated more than E2A−/− cells. Previous studies showed that E2A−/− or E2A/HeB double-deficient DN3 cells incorporate more BrdU than WT DN3 cells, suggesting that these cells proliferate more rapidly than their WT counterparts.18,26 We found that E2A−/− DN2s and DN3s incorporated more BrdU in vivo than WT cells (Figure 7A). In contrast, BrdU incorporation into E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2s and DN3s was comparable with WT (Figure 7A). Therefore, heterozygous deletion of Gata3 limited proliferation of E2A−/− DN2 and DN3 thymocytes. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that heterozygous deletion of Gata3 restored DN2 cell differentiation rather than promoting the expansion of DN3 cells.

Deletion of 1 Gata3 allele restores the ability of E2A−/− DN2 thymocytes to differentiate to the DN3 stage. (A) FACS analysis for BrdU in DN2 or DN3 cells from control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice determined 24 hours after in vivo administration of BrdU. Shaded histogram is negative control. Representative FACS plots from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Limiting dilution analysis of DN3 cell development from control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells cultured on OP9-DL1 for 12 days. Control DN2 cells were plated at 3, 9, and 27 cells/well; E2A−/− and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells were plated at 5, 15, and 45 cells/well with 48 replicate cultures for each cell concentration. On day 12, each well was scored for growth, followed by FACS analysis for surface expression of CD44 and CD25. Results are plotted as percentage of negative cultures versus input cell number. The frequency of responding cells was determined as the input cell concentration where 37% of wells are negative for DN3 cells. (C) Representative FACS plots from single wells seeded with DN2 cells of the indicated genotype. (D) Percentage of DN3 cells in each positive well (with the highest number of cells plated) of control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3Δ/+ DN2s culture; *P < .05.

Deletion of 1 Gata3 allele restores the ability of E2A−/− DN2 thymocytes to differentiate to the DN3 stage. (A) FACS analysis for BrdU in DN2 or DN3 cells from control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ mice determined 24 hours after in vivo administration of BrdU. Shaded histogram is negative control. Representative FACS plots from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Limiting dilution analysis of DN3 cell development from control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells cultured on OP9-DL1 for 12 days. Control DN2 cells were plated at 3, 9, and 27 cells/well; E2A−/− and E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells were plated at 5, 15, and 45 cells/well with 48 replicate cultures for each cell concentration. On day 12, each well was scored for growth, followed by FACS analysis for surface expression of CD44 and CD25. Results are plotted as percentage of negative cultures versus input cell number. The frequency of responding cells was determined as the input cell concentration where 37% of wells are negative for DN3 cells. (C) Representative FACS plots from single wells seeded with DN2 cells of the indicated genotype. (D) Percentage of DN3 cells in each positive well (with the highest number of cells plated) of control, E2A−/−, and E2A−/−Gata3Δ/+ DN2s culture; *P < .05.

To determine whether the increased number of E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN3 cells was the consequence of restored T cell–lineage differentiation or survival/accumulation of DN3 cells, we quantified the frequency of DN2 cells capable of generating DN3-like cells. As expected, the frequency of E2A−/− DN2 cells that gave rise to DN3-like cells was lower than from control DN2 cells (Figure 7B). Moreover, the E2A−/− DN2 cells that produced DN3-like cells generated only a low percentage of DN3 seconds and produced a large population of CD44+CD25lo cells (Figure 7C-D). In contrast, the frequency of E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells that progressed to the DN3-like stage was similar to WT cells (Figure 7A-C). Moreover, individual E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2s generated more DN3-like cells in any given well than E2A−/− DN2s (Figure 7D). Nonetheless, similar to E2A−/− DN2s, E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2s consistently gave rise to cells that also adopted the alternative fates (Figure 7C). Taken together, our data indicated that heterozygous deletion of Gata3 augmented the ability of E2A−/− DN2 cells to generate T cell–committed DN3 cells without affecting the frequency of cells that give rise to NK cells.

Discussion

We identified a novel role for the E2A transcription factors in controlling the T cell–differentiation potential of DN2 thymocytes. E2A impeded NK-cell differentiation from DN2 thymocytes and limited the expression of GATA3, thereby restraining DN2 cell proliferation and promoting T-cell differentiation. Our study is the first to identify a physiologic mechanism to limit GATA3 at this stage of development and to implicate GATA3 in the excessive proliferation of E2A−/− DN thymocytes. The ability of GATA3 to derail T-cell development indicates a critical difference between the regulatory networks that drive B-lymphocyte and T-lymphocyte commitment. In B lymphocytes, E2A initiates a self-sustaining feed-forward pathway in which each transcription factor activates the downstream component, which then feeds back to enforce the expression of the upstream factor while cooperatively activating B cell–specific genes and promoting the repression of non–B-cell genes. In contrast, T lymphocyte lineage commitment involves both feed-forward (induction of Gata3 by NOTCH1) and repressive mechanisms (restriction of Gata3 by E2A) that ensure the appropriate expression of a transcription factor that can promote T-cell development only within a narrow concentration range.

A previous study implicated Notch1 as the essential E2A target whose deregulated expression prevents T-cell differentiation in E2A−/− mice.10 Nonetheless, we found that Notch1 mRNA was expressed at sufficient levels in E2A−/− thymocytes to promote expression of Deltex1 and Gata3. Therefore, Notch signaling is functional in E2A−/− DN2 cells and sufficient to support T-cell differentiation. Notch1 is a target of Notch signaling; therefore, although E2A−/− thymus-seeding cells express low levels of Notch1,9 sufficient Notch-signaling may occur in the thymus to up-regulate Notch1 mRNA. NOTCH1 can restrain the ability of high GATA3-expressing DN2s to adopt the mast cell fate,6 and E2A−/− DN2s did not generate mast cells in vitro, suggesting that the slight decrease in Notch1 may have had no consequence. However, these cells may have failed to adopt the mast cell fate because E2A:SCL heterodimers are necessary for mast cell differentiation.6,27 In contrast, E2A−/− DN2s readily generated NK cells when cultured on OP9-DL1, suggesting that the level of Notch signaling was insufficient to restrain NK-cell differentiation or, alternatively, that E2A was necessary to prevent NK-cell differentiation even in the presence of Notch. On the basis of the known requirement for ID2 in NK-cell differentiation28 and previous studies that show the dose responsiveness of NK-cell inhibition by NOTCH1,10,29 we favor the latter explanation.

We conclude that the overproduction of GATA3 in E2A−/− DN2s antagonized T-cell development and caused an increase in NK-cell progenitors in vivo even though E2A deficiency was the primary mechanism that allowed for NK-cell development. The hypothesis that the overproduction of GATA3 underlies the arrested T-cell development in E2A−/− progenitors is supported by the increased frequency of DN3 cells generated in vitro from E2A−/− MPPs after knocking down Gata3 with an siRNA and after heterozygous deletion of Gata3 in E2A−/− hematopoietic cells. Although heterozygous deletion of Gata3 had little effect on the frequency of E2A−/− DN2 cells that generated alternative fates, in vivo the frequency and number of Lin−CD117loCD44hiCD25lo cells was reduced. We propose that GATA3 influences the number of cell divisions a DN2 cell undergoes before making the choice between T-cell differentiation and alternative fates. Thus, reducing GATA3 decreased DN2 cell “self-renewal,” augmented T-cell differentiation, and resulted in fewer Lin−CD117loCD44hiCD25lo cells in the thymus. We propose that in vitro E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells retained the potential for NK-cell/alternative fate differentiation but made a cell fate choice after fewer divisions. If this model is correct, then E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN2 cells must have undergone some, although limited, “self-renewal” in vitro before T-cell commitment such that most wells contained both DN3 and NK cells. A role for GATA3 in augmenting self-renewal is consistent with the ability of ectopic GATA3 to promote T-cell transformation in transgenic mice.30,31

In vivo, E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN3 cells did not recover to the number of WT DN3 cells, although the ratio of Lin−CD117lo/−CD44+CD25lo to DN3 cells changed dramatically. The multiple functions of E2A in DN3 cells probably contributed to this observation. E2A is required for proper rearrangement and expression of TCRβ32 and probably controls the expression of multiple DN3 cell genes.20 In addition, E2A−/− DN3 cells are able to pass β-selection without expressing a functional pre-TCR and may rapidly differentiate to the DP stage.33,34 Another potential explanation for the failure of E2A−/−Gata3+/Δ DN3 cells to recover to WT numbers is that heterozygous deletion of Gata3 did not reduce GATA3 sufficiently to fully restore DN3 numbers. It is possible that deletion of 1 allele of Gata3 resulted in a < 50% reduction in GATA3 because GATA3 stability can be affected by interactions with other transcription factors35,36 and GATA3 can be regulated translationally.37 In vitro we found that heterozygous deletion of Gata3 was sufficient to restore the frequency of E2A−/− DN2 cells that could differentiate to the DN3 stage. Therefore, a 50% reduction in Gata3 alleles is sufficient to at least partially alleviate the differentiation block in E2A−/− thymocytes.

The question of how E2A limits Gata3 expression warrants further investigation. Gata3 may be a direct target of E2A because E2A binds near the Gata3 gene in T cells.20,38 E proteins can function as transcriptional repressors when associated with the class II bHLH protein Tal1/SCL, which is expressed in DN2 cells.39,40 However, direct regulation of Gata3 by E2A:SCL is unlikely because transgenic expression of SCL in T cells phenocopies E2A deficiency, implying that SCL inhibits E2A function.41,42 Another possibility is that E2A target genes such as Gfi1 and Gfi1b function as repressors of Gata3.17,21 However, Gfi1−/− MPPs generated DN3 cells in vitro, showing that these cells do not phenocopy E2A−/− MPPs. Therefore, although GFI1 and/or GFI1B may play a role in limiting Gata3 expression, GFI1 alone is not essential. We hypothesize that multiple targets of E2A participate in restricting Gata3 expression in DN2 cells. An analysis of the cis-regulatory elements that control Gata3 will be necessary to determine how Gata3 is controlled during T-cell development.

The mechanisms by which GATA3 arrests T-cell development have not been elucidated. A previous study suggested that GATA3 induces the expression of the Notch signaling antagonist DELTEX1, which can reduce Notch signaling and block T-cell development.43 However, E2A−/− MPPs cultured on OP9-DL1 had lower expression of Deltex1 mRNA than WT cells.10 In addition, Deltex1 mRNA was expressed at near WT levels in E2A−/− DN2 or DN3 cells. We did observe high expression of Deltex1 and Id2 in E2A−/− Lin−CD117loCD44+CD25lo thymocytes, which differentiated into NK cells in vitro. These findings suggest that this population may have confounded the previous studies. Nonetheless, removing Deltex1 from Id1 transgenic mice, which have reduced E protein activity, had a modest effect on early T-cell development, consistent with previous data showing that an increase in Notch signaling in E2A−/− cells can augment T-cell development.10,43 However, DELTEX1 does not appear to be a main contributor to GATA3-induced developmental arrest in E2A−/− DN2 cells.

It remains to be determined whether high concentrations of GATA3 target the same genes (altering their level of expression) or a unique set of genes (resulting in ectopic expression) from those regulated by lower concentrations of GATA3. Ectopic expression of GATA3 alters the expression of multiple genes, including Il7ra, Sfpi1, Ptcra, and Rag1, but GATA3 only binds directly to Rag1 in T-lymphocyte progenitors.5,6,40,44 Interestingly, a comparison of the genes that are differentially expressed in E2A−/− DN2s with genes that are bound by GATA3 in DN1, DN2, or DP thymocytes showed that only a few E2A-dependent DN2 genes were bound by GATA3, and these were largely T cell–associated genes, including Rag1, Bcl11b, Gfi1, and Cd3e.40 In contrast, a larger portion of the genes that increased in E2A−/− DN2 cells were bound by GATA3, including Lgals3, Rora, Sema4f, Ccr6, Icos, Id2, Zbtb16, Il4, Itgb2, and Itgb3.40 These observations raise the possibility that GATA3 activates genes in E2A−/− cells and that lower concentrations of GATA3 may fail to activate these genes or even repress them. This hypothesis is consistent with previous studies that reported that GATA3 functions are concentration dependent and may be influenced by interactions with other transcription factors. For example, high concentrations of GATA3 antagonize PU.1 function in DN2s, whereas low concentrations of GATA3 synergize with PU.1 to produce a gene expression signature that allows for T-cell lineage commitment.6,45,46 Additional studies will be necessary to determine how the elevation of GATA3 influences the differentiation and commitment of T-lymphocyte progenitors.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Avinash Bhandoola for assistance with identification of ETPs and helpful suggestions; Dr Jose Alberola-Ila for the Banshee-Gata3 siRNA vector; Dr Ivan Moskovitz for the Tie2-Cre mice; Drs I-Cheng Ho and Sun-Yun Pai for the Gata3+/fl mice; Drs Sheila Dias and Mary Yui for help with the GATA3 staining; Dr Renee de Pooter for comments on the manuscript; and members of the Kee laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA099978, R01 AI079213, and R21 AI096530). B.L.K. is supported by a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar Award. S.M. was supported by the University of Chicago Medical Scientist Training Program T32 GM07281, and K.R. was supported by T32 GM38663 and R01 CA099978-S1.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.X. designed and performed experiments and helped write the manuscript; T.C. and S.M. contributed to some experiments; K.R. analyzed microarray data; M.S. performed microarray analysis; and B.L.K. designed experiments, wrote the manuscript, and obtained funding for the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Barbara L. Kee, Department of Pathology, The University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Ave, MC1089, Chicago, IL 60637; e-mail: bkee@bsd.uchicago.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal