Key Points

Ribosome biogenesis and hematopoiesis are impaired in iPSCs from DBA patients.

The abnormalities of DBA iPSCs are ameliorated by genetic restoration of the defective ribosomal protein genes.

Abstract

Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a congenital disorder with erythroid (Ery) hypoplasia and tissue morphogenic abnormalities. Most DBA cases are caused by heterozygous null mutations in genes encoding ribosomal proteins. Understanding how haploinsufficiency of these ubiquitous proteins causes DBA is hampered by limited availability of tissues from affected patients. We generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from fibroblasts of DBA patients carrying mutations in RPS19 and RPL5. Compared with controls, DBA fibroblasts formed iPSCs inefficiently, although we obtained 1 stable clone from each fibroblast line. RPS19-mutated iPSCs exhibited defects in 40S (small) ribosomal subunit assembly and production of 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Upon induced differentiation, the mutant clone exhibited globally impaired hematopoiesis, with the Ery lineage affected most profoundly. RPL5-mutated iPSCs exhibited defective 60S (large) ribosomal subunit assembly, accumulation of 12S pre-rRNA, and impaired erythropoiesis. In both mutant iPSC lines, genetic correction of ribosomal protein deficiency via complementary DNA transfer into the “safe harbor” AAVS1 locus alleviated abnormalities in ribosome biogenesis and hematopoiesis. Our studies show that pathological features of DBA are recapitulated by iPSCs, provide a renewable source of cells to model various tissue defects, and demonstrate proof of principle for genetic correction strategies in patient stem cells.

Introduction

Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA; OMIM105650) is a rare congenital anemia with erythroid (Ery) hypoplasia, developmental abnormalities, growth retardation, and an increased risk of malignancy.1 About half of DBA cases are caused by heterozygous mutations in genes encoding ribosomal proteins, leading to haploinsufficiency2 or, less frequently, dominant-negative effects3 with consequent defects in ribosome formation and/or function. RPS19 and RPL5 mutations are the most frequently mutated genes, representing ∼25% and 7% of all cases.4 RPS19 is required for ribosomal RNA (rRNA) processing and assembly of the small 40S ribosomal subunit.5 RPL5 binds 5S rRNA thereby facilitating its transport to the nucleolus for assembly into the 60S ribosomal subunit.6

How ribosomal defects produce the unique constellation of DBA abnormalities is not understood. RPS19-deficient animal models, including genetically manipulated zebrafish and mice, provide insights into the pathophysiology of DBA,7-11 although the extent to which they recapitulate the hematopoietic defect in humans is not clear. The Ery defects of DBA have been characterized further through RPS19 knockdown in normal hematopoietic cells12,13 and examination of primary hematopoietic progenitors from affected patients.14-16 The pathophysiology of RPL5 mutations is largely unstudied and no relevant animal models are available, although this represents a relatively common DBA gene associated with a particularly high incidence of craniofacial, heart, and thumb malformations.17 Studies of affected tissues from DBA patients complement animal model studies. However, obtaining patient-derived DBA cells is limited by the rarity of the disease (especially non-RPS19 mutant forms), and the invasive nature of tissue sampling. Moreover, Ery progenitors are reduced in at least some forms of DBA due to enhanced apoptosis,15 which precludes obtaining the relevant affected cell type directly from patients. Consequently, adequate human cellular models for DBA are insufficient.

Findings that human somatic tissues can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) via ectopic expression of several transcription factors have created new opportunities for disease modeling.18 iPSCs, which resemble embryonic stem cells (ESCs), can be differentiated to form blood lineages in vitro, and therefore offer potentially relevant tissue sources for studies of inherited blood disorders, including DBA. Moreover, patient-derived iPSCs are amenable to genetic manipulation and gene correction, providing a promising strategy for cellular therapy. We generated iPSCs from 2 DBA patients, 1 carrying a RPS19 mutation and the other a RPL5 mutation. Despite a low reprogramming efficiency, iPSCs were obtained in both cases. These lines exhibited ribosomal and hematopoietic defects of DBA that were reversed upon restored expression of the mutated gene. Our studies provide new tools for investigating DBA and more generally, offer proof of principle that patient-derived iPSCs recapitulate human blood disorders.

Methods

Creation and differentiation of iPSCs from DBA patients

The human samples used to make iPSCs were collected under a protocol approved by the institutional review board at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Skin fibroblasts were reprogrammed using STEMCCA vector, and differentiated into blood lineages, as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website) and supplemental Figure 1. The DBA iPSCs described in this study are available upon request.

Detailed methods for analysis of ribosome biogenesis, gene targeting of the AAVS1 locus in iPSCs, flow cytometry, western blotting, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are described in supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

The Student t test was performed and P values were determined using the 2-tailed t test for groups with equal variance.

Results

Generation of iPSCs from an RPS19-mutated DBA patient

We used a lentiviral reprogramming virus to generate iPSCs from dermal fibroblasts of a 14-year-old male DBA patient who is heterozygous for the RPS19 mutation c.376 C>T, p.Q126X.19 We generated wild-type (WT) control iPSCs from skin fibroblasts of normal individuals using a similar reprogramming cassette (see supplemental Methods for details). The DBA patient is transfusion dependent and has no congenital anomalies. The C-terminal truncated protein predicted by this mutation is not expressed in ESCs or 293T cells (supplemental Figure 2), consistent with observations that many DBA-associated RPS19 mutant proteins, particularly those with premature stop codons, are either not expressed due to nonsense-mediated decay,20 or eliminated rapidly by proteasomal degradation.21,22 Control fibroblasts generated iPSC colonies at a frequency of 0.03%. The DBA fibroblasts generated iPSC colonies at a reduced frequency (0.0045%). Moreover, upon further passaging, most DBA clones exhibited spontaneous differentiation or death. Overall, we attempted to expand 18 RPS19-mutated colonies. Only 1 of these clones (5%), termed RPS19+/p.Q126X, proliferated normally and retained stable characteristics of iPSCs upon prolonged culture. These include undifferentiated morphology, expression of pluripotency markers, normal karyotype, and capacity to form 3 germ layers in teratomas (supplemental Figure 3). The RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs were heterozygous for the patient DBA mutation (supplemental Figure 3A).

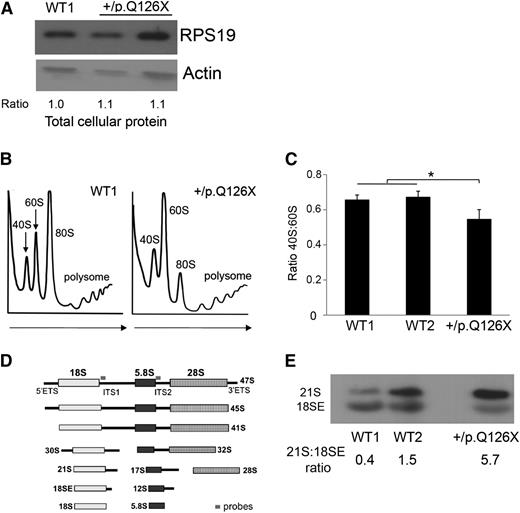

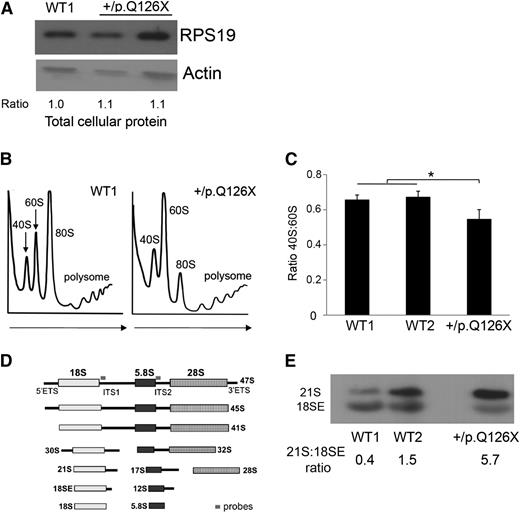

Perturbed ribosome biogenesis in DBA iPSCs heterozygous for an RPS19 mutation

The mutant iPSCs expressed a normal steady-state level of total cellular RPS19 (Figure 1A). However, genetic haploinsufficiency of this protein could still be limiting for ribosome assembly. In support, RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit reduced RPS19 protein in the nucleus, suggesting that the protein may be limiting in the nucleolus, where ribosome assembly occurs (see Figure 4C-D described below and “Discussion”). To investigate this, we used sucrose gradient centrifugation to analyze polysome profiles in the mutant and 2 WT lines. Compared with the WT lines, RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibited decreased ratio of 40S:60S polysomes (Figure 1B-C). Ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency can also perturb pre-rRNA processing.19,23 We performed Northern blotting using radiolabeled probes designed to detect specific mature rRNAs and their precursors (Figure 1D-E). The RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC line was defective in 18S rRNA processing, with accumulation of 21S rRNA, the immediate precursor of 18SE rRNA, which is transported to the cytoplasm before final processing to mature 18S rRNA.24 These results demonstrate impaired assembly of the 40S ribosomal subunit and faulty 21S pre-rRNA processing in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs.

Ribosome biogenesis defects in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs and a WT (WT1) control line. Lane 2 represents the mutant iPSC line examined throughout this manuscript. Lane 3 represents an iPSC line that did not fulfill all of the pluripotency criteria and therefore was not examined further. Ratio of RPS19:actin determined by densitometry is shown relative to the value for the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (B) Sucrose gradient polysome profiles showing reduced 40S:60S ratio in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs compared with a WT control line. Arrows show direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (C) Histogram summarizing 3 independent polysome profiling experiments examining RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs and 2 different WT lines. The 40S:60S ratio was significantly reduced in the mutated clone (0.55 vs 0.66, *P < .05). (D) Diagram showing rRNA maturation and Northern blot probes complementary to ITS1 (for the 40S unit) and ITS2 (for the 60S unit), used in Figures 1E, 4G, and 6D. The probe sequences are shown in supplemental Table 3. (E) Northern blot analysis of iPSCs using the ITS1 probe. RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit relative accumulation of 21S pre-rRNA compared with WT iPSCs. The 21S:18SE pre-rRNA ratios determined by densitometry scanning is shown at the bottom of the panels. ITS, internal transcribed spacer.

Ribosome biogenesis defects in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs and a WT (WT1) control line. Lane 2 represents the mutant iPSC line examined throughout this manuscript. Lane 3 represents an iPSC line that did not fulfill all of the pluripotency criteria and therefore was not examined further. Ratio of RPS19:actin determined by densitometry is shown relative to the value for the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (B) Sucrose gradient polysome profiles showing reduced 40S:60S ratio in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs compared with a WT control line. Arrows show direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (C) Histogram summarizing 3 independent polysome profiling experiments examining RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs and 2 different WT lines. The 40S:60S ratio was significantly reduced in the mutated clone (0.55 vs 0.66, *P < .05). (D) Diagram showing rRNA maturation and Northern blot probes complementary to ITS1 (for the 40S unit) and ITS2 (for the 60S unit), used in Figures 1E, 4G, and 6D. The probe sequences are shown in supplemental Table 3. (E) Northern blot analysis of iPSCs using the ITS1 probe. RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit relative accumulation of 21S pre-rRNA compared with WT iPSCs. The 21S:18SE pre-rRNA ratios determined by densitometry scanning is shown at the bottom of the panels. ITS, internal transcribed spacer.

Defective hematopoiesis by RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Four-day-old EBs were disaggregated and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD31+/KDR+ cells, which represent prehematopoietic mesoderm. A representative experiment is shown on the left. The combined results of multiple experiments analyzing 3 WT control lines and RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs are shown on the right. The black bars in the graph represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For iPSC lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares. (B) Eight-day-old EBs were disaggregated and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD43+ cells, which represent the first hematopoietic progenitors to emerge from ESC or iPSC differentiation. A representative experiment is shown on the left. The combined results of 3 independent experiments are shown on the right. *P < .05. (C) Hematopoietic progenitor assay. EBs were dissociated at day 8 of differentiation and seeded into methylcellulose containing EPO, IL-3, SCF, and GM-CSF. CFU-GM and Ery colonies were enumerated 7 to 9 days after plating. *P < .05; NS (P = .17); n = 4 separate experiments, each in triplicate. CFU-GM, colony forming unit-granulocyte macrophage; NS, not significant.

Defective hematopoiesis by RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Four-day-old EBs were disaggregated and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD31+/KDR+ cells, which represent prehematopoietic mesoderm. A representative experiment is shown on the left. The combined results of multiple experiments analyzing 3 WT control lines and RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs are shown on the right. The black bars in the graph represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For iPSC lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares. (B) Eight-day-old EBs were disaggregated and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD43+ cells, which represent the first hematopoietic progenitors to emerge from ESC or iPSC differentiation. A representative experiment is shown on the left. The combined results of 3 independent experiments are shown on the right. *P < .05. (C) Hematopoietic progenitor assay. EBs were dissociated at day 8 of differentiation and seeded into methylcellulose containing EPO, IL-3, SCF, and GM-CSF. CFU-GM and Ery colonies were enumerated 7 to 9 days after plating. *P < .05; NS (P = .17); n = 4 separate experiments, each in triplicate. CFU-GM, colony forming unit-granulocyte macrophage; NS, not significant.

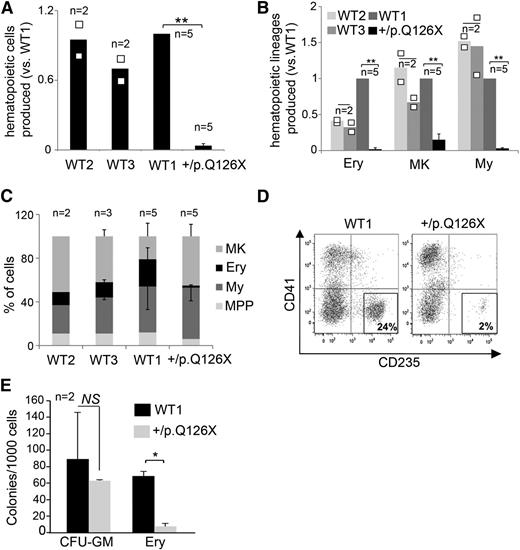

RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit panhematopoietic defects with the Ery lineage most strongly affected. (A) Relative ratio of hematopoietic cells released by WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs at day 14 of differentiation. Cell numbers are normalized to those produced by the WT1 clone, which was analyzed consistently in all experiments. Cultures containing roughly equal numbers of EBs were analyzed. WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs were of similar size. **P = .002; n = 5 separate experiments. (B) Quantification of hematopoietic lineages in the experiment from panel A. MK (CD41+/CD235−), Ery (CD41+/CD235+), My (CD41−/CD235−, CD45+) cells were identified by flow cytometry in WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EB cultures at day 14 of differentiation. **P < .01; n = 5 separate experiments. (C) Relative frequency (%) of each lineage present in day 14 EB cultures represented in experiments from panels A and B. The proportion of Ery cells was decreased in cultures derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs (RPS19+/p.Q126X vs WT1: 2% vs 19%, n = 5, P < .01). MPP refers to the CD41+/CD235+ primitive multipotential progenitor population that arises transiently in day 7 to 8 EB cultures and disappears gradually as the cells differentiate into mature lineages.25,27 (D) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing reduced proportion of Ery cells (CD235+/CD41−) produced by RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs compared with WT1 control in day 14 EB cultures. (E) Hematopoietic progenitor assay. CD43+ progenitors released from day 8 EBs were seeded in triplicate into methylcellulose containing EPO, IL-3, SCF, and GM-CSF. CFU-GM and Ery colonies were enumerated 7 to 9 days after plating. The Ery progenitors were reduced in the RPS19+/p.Q126X samples compared with WT1 control (*P < .05). The bars in the graphs (A-B) represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares. MK, megakaryocytic; My, myeloid.

RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit panhematopoietic defects with the Ery lineage most strongly affected. (A) Relative ratio of hematopoietic cells released by WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs at day 14 of differentiation. Cell numbers are normalized to those produced by the WT1 clone, which was analyzed consistently in all experiments. Cultures containing roughly equal numbers of EBs were analyzed. WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs were of similar size. **P = .002; n = 5 separate experiments. (B) Quantification of hematopoietic lineages in the experiment from panel A. MK (CD41+/CD235−), Ery (CD41+/CD235+), My (CD41−/CD235−, CD45+) cells were identified by flow cytometry in WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X EB cultures at day 14 of differentiation. **P < .01; n = 5 separate experiments. (C) Relative frequency (%) of each lineage present in day 14 EB cultures represented in experiments from panels A and B. The proportion of Ery cells was decreased in cultures derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs (RPS19+/p.Q126X vs WT1: 2% vs 19%, n = 5, P < .01). MPP refers to the CD41+/CD235+ primitive multipotential progenitor population that arises transiently in day 7 to 8 EB cultures and disappears gradually as the cells differentiate into mature lineages.25,27 (D) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing reduced proportion of Ery cells (CD235+/CD41−) produced by RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs compared with WT1 control in day 14 EB cultures. (E) Hematopoietic progenitor assay. CD43+ progenitors released from day 8 EBs were seeded in triplicate into methylcellulose containing EPO, IL-3, SCF, and GM-CSF. CFU-GM and Ery colonies were enumerated 7 to 9 days after plating. The Ery progenitors were reduced in the RPS19+/p.Q126X samples compared with WT1 control (*P < .05). The bars in the graphs (A-B) represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares. MK, megakaryocytic; My, myeloid.

Genetic rescue of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs restores 40S ribosomal subunit biogenesis. (A) Gene correction strategy. The constitutively active AAVS1 “safe harbor” locus is shown on the top line and the targeting construct is shown below. cDNA expression cassettes driving expression of WT RPS19 or GFP cDNAs under the chicken actin promoter (CAGG) were inserted by zinc finger-mediated homologous recombination into intron 1 of AAVS1. HA, homologous arms left (L) and right (R); SA-2A-Puro-PA, puromycin drug resistance cassette. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of AAVS1-targeted iPSCs using primers specific for transgenic RPS19 cDNA. Expression was detected specifically in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs after heterozygous integration of the RPS19 cDNA into the AAVS1 locus. RPS19 expression is normalized to the cyclophilin expression level. (C) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in whole-cell lysates of WT1, RPS19+/p.Q126X parental iPSCs (designated as “ – ”) and RPS19+/p.Q126X clones with AAVS1-integrated GFP or RPS19 transgenes. The ratio of RPS19:actin determined by densitometry is shown relative to the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (D) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in nuclear extracts of WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X clones with AAVS1-integrated GFP or RPS19 transgenes. The RPS19:fibrillarin ratios determined by densitometry are shown relative to the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (E) Representative polysome profiles in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or WT RPS19 cDNA expression cassettes integrated into the AAVS1 locus. Arrows show direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (F) Summary of 3 independent experiments quantifying the 40S:60S ribosome subunit ratio in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or WT RPS19 cDNA expression cassettes integrated into the AAVS1 locus. Experiments were performed as illustrated in panel E. *P < .05. (G) Northern blot analysis using the ITS1 probe (see Figure 1D) in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs with GFP or RPS19 cDNA introduced into the AAVS1 locus. RPS19 rescue of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs specifically alleviates impaired processing of 21S pre-rRNA. The ratios of 21S:18SE RNAs determined by densitometry scanning are shown.

Genetic rescue of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs restores 40S ribosomal subunit biogenesis. (A) Gene correction strategy. The constitutively active AAVS1 “safe harbor” locus is shown on the top line and the targeting construct is shown below. cDNA expression cassettes driving expression of WT RPS19 or GFP cDNAs under the chicken actin promoter (CAGG) were inserted by zinc finger-mediated homologous recombination into intron 1 of AAVS1. HA, homologous arms left (L) and right (R); SA-2A-Puro-PA, puromycin drug resistance cassette. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of AAVS1-targeted iPSCs using primers specific for transgenic RPS19 cDNA. Expression was detected specifically in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs after heterozygous integration of the RPS19 cDNA into the AAVS1 locus. RPS19 expression is normalized to the cyclophilin expression level. (C) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in whole-cell lysates of WT1, RPS19+/p.Q126X parental iPSCs (designated as “ – ”) and RPS19+/p.Q126X clones with AAVS1-integrated GFP or RPS19 transgenes. The ratio of RPS19:actin determined by densitometry is shown relative to the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (D) Western blot showing RPS19 protein in nuclear extracts of WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X clones with AAVS1-integrated GFP or RPS19 transgenes. The RPS19:fibrillarin ratios determined by densitometry are shown relative to the WT1 sample, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (E) Representative polysome profiles in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or WT RPS19 cDNA expression cassettes integrated into the AAVS1 locus. Arrows show direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (F) Summary of 3 independent experiments quantifying the 40S:60S ribosome subunit ratio in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or WT RPS19 cDNA expression cassettes integrated into the AAVS1 locus. Experiments were performed as illustrated in panel E. *P < .05. (G) Northern blot analysis using the ITS1 probe (see Figure 1D) in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs with GFP or RPS19 cDNA introduced into the AAVS1 locus. RPS19 rescue of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs specifically alleviates impaired processing of 21S pre-rRNA. The ratios of 21S:18SE RNAs determined by densitometry scanning are shown.

RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit defective hematopoiesis

We next investigated the ability of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs to produce hematopoietic lineages upon induced differentiation. We generated embryoid bodies (EBs) using a serum-free differentiation protocol that uses sequential addition of cytokines to support the production of mesoderm followed by its differentiation into hematopoietic lineages25 (supplemental Methods and supplemental Figure 1). RPS19+/p.Q126X and WT iPSCs formed EBs at similar frequencies and sizes. At day 4 of differentiation, WT and RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs produced similar frequencies of CD31+/KDR+ cells (Figure 2A), which represent a prehematopoietic mesodermal population.26 However, the proportion of CD43+ cells, which represents the first population of hematopoietic progenitors to emerge in ESC/iPSC differentiation cultures,25,27 was decreased in day 8 EBs derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs (Figure 2B). To test directly for hematopoietic progenitors, we disaggregated EBs into single cells and seeded them into methylcellulose colony assays. Compared with controls, the frequency of Ery colony-forming cells was reduced in RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs by ∼12-fold compared with control EBs (Figure 2C). There was also a trend toward decreased myeloid progenitors within RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .17).

Beginning at ∼day 8, EBs release into the growth medium a population of multilineage hematopoietic progenitors (CD41+/CD34+/CD43+/CD235+) that differentiate into megakaryocyte, Ery and myeloid cells by ∼day 14 of liquid culture (Chou et al,25 Vodyanik et al,27 and supplemental Figure 1). At this time point, cultures containing roughly equal numbers of WT or RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs were harvested, enumerated, and analyzed for lineage markers. The total number of hematopoietic cells in suspension that were produced by RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs was ∼25- to 35-fold reduced compared with EBs generated by 3 different clones of WT iPSCs (Figure 3A). This difference exceeds the ∼10-fold variation in production of hematopoietic cells that can occur between different WT iPSCs or ESCs28 and is therefore likely caused by the DBA mutation. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the RPS19+/p.Q126X mutant iPSCs generated decreased absolute numbers of megakaryocyte, Ery and myeloid cells (Figure 3B). Moreover, the hematopoietic cell pool produced by day 14 RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs contained a reduced proportion of Ery cells (Figure 3C-D). Consistent with this finding, methylcellulose colony assays of hematopoietic progenitors released by day 8 RPS19+/p.Q126X EBs demonstrated reduced levels of Ery progenitors compared with the WT1 control (Figure 3E). Together, these data demonstrate that RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibit 2 defects: globally impaired hematopoiesis affecting multipotent progenitors and defective erythropoiesis from the progenitors that do emerge.

Gene correction restores ribosome assembly and hematopoiesis to RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs

Different clones of WT iPSCs produce hematopoietic lineages at frequencies that can vary by 10-fold.28 Thus, it is important to demonstrate that reduced hematopoiesis observed in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs (vs WT iPSCs) does not simply reflect clonal variation. As noted, we obtained only 1 stable RPS19-mutated iPSC line, despite multiple attempts at reprogramming the mutant fibroblasts. To circumvent this problem and investigate the relationship between the hematopoietic phenotype and the RPS19 functional defect, we used zinc finger nucleases to introduce WT RPS19 cDNA or control green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA expression constructs into the “safe harbor” locus AAVS129 (Figure 4A). We identified clones with a single heterozygous integration (RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP and RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19) by PCR and Southern blot analysis (supplemental Figure 4) and examined one in detail. Expression of the WT RPS19 cDNA transgene was verified by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 4B). Western blotting showed that RPS19 protein was normal in whole-cell extracts of RPS19-haploinsufficient iPSCs (Figure 4C), consistent with the findings presented in Figure 1A. However, RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP iPSCs contained reduced nuclear RPS19 protein compared with RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19 or WT iPSCs (Figure 4D). Thus, in the haploinsufficient line, RPS19 may be limiting in the nucleolus, the site of ribosome assembly. In agreement, polysome profiling revealed that the RPS19 cDNA rescued clone showed a significant increase in the 40S:60S ratio and in the level of active polysomes compared with RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP iPSCs (Figure 4E-F). Northern blot analysis showed that the block to 21S pre-rRNA maturation observed in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs was rescued specifically by RPS19 expression (Figure 4G).

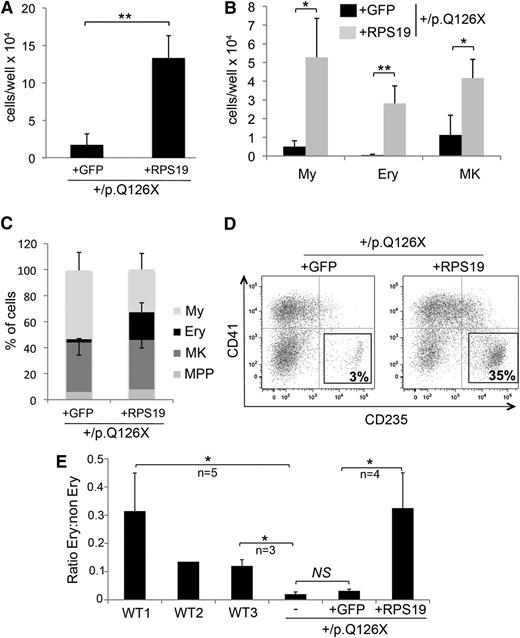

We next investigated whether gene correction restores hematopoiesis in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. Day 14 EBs derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19 iPSCs produced about sevenfold increased total hematopoietic cells compared with EBs that were derived from the control line (RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP) (Figure 5A). This indicates a partial correction of the panhematopoietic defect observed in RPS19-haploinsufficient iPSCs, which exhibited 25- to 35-fold reduced production of hematopoietic progenitors compared with 3 WT control lines (see Figure 3A). The total numbers of committed myeloid, Ery, and megakaryocytic cells produced after in vitro differentiation were increased in the RPS19-rescued line (Figure 5B), reflecting a positive effect on proliferation and/or survival of all hematopoietic lineages. These effects were greatest on the Ery lineage, as the percentage of CD235+ (glycophorin A) erythroblasts was significantly higher in the RPS19-corrected cells compared with the GFP control (Figure 5C-D). Indeed, the proportion of Ery cells generated by the RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19 line (but not the RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP line) was similar to that observed in the WT1 cell line, which generated erythroblasts most efficiently among the 3 WT control cell lines examined (Figure 5E). Thus, restoration of RPS19 relieved defective ribosome biogenesis and rescued hematopoiesis in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. These gene correction data indicate that the reduced hematopoiesis by the DBA patient-derived iPSCs is caused by defective ribosomal synthesis and/or function and not due to clonal variation or irrelevant mutations acquired during iPSC generation or passage.

Gene rescue by RPS19 restores hematopoiesis in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or RPS19 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. **P = .002; n = 4 independent experiments. (B) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs, as shown in panel A, were analyzed by flow cytometry for hematopoietic lineage markers, as described in Figure 3B. **P < .01 for Ery; *P < .05 for MK and My; n = 4 independent experiments. (C) Analysis of data from panel B showing relative production of different hematopoietic lineages in the RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC sublines with GFP or RPS19 cDNA transgenes. Note that erythropoiesis is selectively enhanced in the RPS19-rescued cells (% CD235+: 21 vs 2.5, P = .009); n = 4 independent experiments. (D) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing the percentage of CD235+ Ery cells produced in differentiation cultures of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or RPS19 cDNA transgenes. (E) The relative proportion of Ery cells produced by day 14 EBs derived from 3 WT iPSC lines, RPS19+/p.Q126X parental iPSCs (designated as “–”) and its subclones containing GFP or RPS19 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. The variable proportions of erythroblasts observed between the 3 WT lines represents reproducible differences in hematopoietic potential among different iPSC clones. Note that erythropoiesis is restored in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs by RPS19 cDNA, but not by GFP cDNA. *P < .05, n = 4 independent experiments comparing RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP and RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19 clones.

Gene rescue by RPS19 restores hematopoiesis in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs. (A) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs derived from RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or RPS19 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. **P = .002; n = 4 independent experiments. (B) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs, as shown in panel A, were analyzed by flow cytometry for hematopoietic lineage markers, as described in Figure 3B. **P < .01 for Ery; *P < .05 for MK and My; n = 4 independent experiments. (C) Analysis of data from panel B showing relative production of different hematopoietic lineages in the RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC sublines with GFP or RPS19 cDNA transgenes. Note that erythropoiesis is selectively enhanced in the RPS19-rescued cells (% CD235+: 21 vs 2.5, P = .009); n = 4 independent experiments. (D) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing the percentage of CD235+ Ery cells produced in differentiation cultures of RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSC subclones with GFP or RPS19 cDNA transgenes. (E) The relative proportion of Ery cells produced by day 14 EBs derived from 3 WT iPSC lines, RPS19+/p.Q126X parental iPSCs (designated as “–”) and its subclones containing GFP or RPS19 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. The variable proportions of erythroblasts observed between the 3 WT lines represents reproducible differences in hematopoietic potential among different iPSC clones. Note that erythropoiesis is restored in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs by RPS19 cDNA, but not by GFP cDNA. *P < .05, n = 4 independent experiments comparing RPS19+/p.Q126X + GFP and RPS19+/p.Q126X + RPS19 clones.

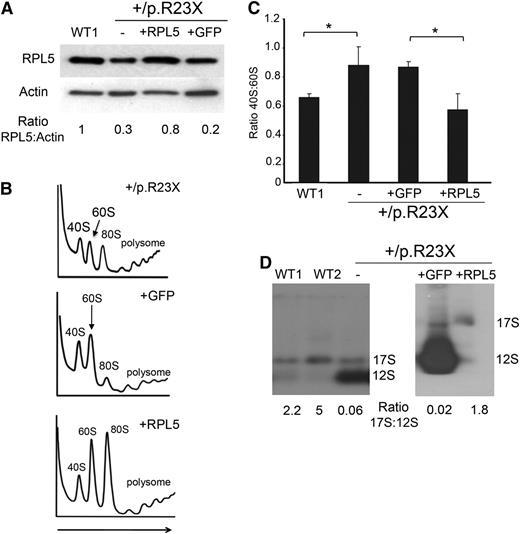

RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs exhibit defective ribosome assembly and hematopoiesis

To determine whether our findings for RPS19-mutated iPSCs can be generalized to other ribosomal protein defects, we analyzed iPSCs derived from fibroblasts of a DBA patient with an RPL5 mutation. This patient is steroid dependent and has mild bilateral thumb abnormalities, mild facial dysmorphologies, and hypogonadism. The RPL5 mutation, c.67C>T, p.R23X, causes haploinsufficiency by introducing an early termination codon.19 Most iPSC clones from RPL5+/p.R23X fibroblasts were unstable and could not be propagated, similar to what we observed for the RPS19-mutated fibroblasts. However, we derived 1 clone, termed RPL5+/p.R23X, which retained a normal karyotype and standard pluripotency features after 20 passages (supplemental Figure 5). We verified that this iPSC line is heterozygous for the RPL5 c.67C>T DBA mutation (supplemental Figure 5A). We also generated a genetically modified RPL5+/p.R23X subclone by using zinc finger-mediated homologous recombination to introduce WT RPL5 or control GFP cDNAs into the AAVS1 locus, similar to what we did for the RPS19-mutated iPSC line (see Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 4). The RPL5-haploinsufficient (RPL5+/p.R23X and RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP) iPSC clones exhibited >50% reduced expression of RPL5 detected by western blot (Figure 6A, lane 2 and 4 in comparison with control lane 1); this was corrected in the RPL5-rescued clone (lane 3). Polysome profiling showed that RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs contained increased 40:60S ribosomal subunit ratios compared with WT control iPSCs, indicative of impaired ribosome assembly (Figure 6B-C). RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs were also defective in rRNA processing with accumulation of 12S pre-rRNA (Figure 6D). These defects were almost completely reverted specifically by RPL5 rescue (Figure 6B-D).

RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs exhibit ribosomal defects that are rescued by gene correction. (A) Western blot for RPL5 protein in WT1 and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (first 2 lanes). Gene-corrected and control sublines were generated by introducing WT RPL5 or GFP cDNA, respectively, into the AAVS1 locus of RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (lanes 3 and 4). Ratio of RPL5:actin analyzed by densitometry is shown relative to the WT1 clone, which is assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (B) Polysome profiling of RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs and sublines with GFP or WT RPL5 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. A polysome profile of a WT iPSC line is shown in Figure 1B. Arrow shows direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (C) Summary of 3 polysome profiling experiments showing increased ratio of 40S:60S ribosomal subunits in RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs (lanes 2 and 3), compared with WT (lane 1) or RPL5-rescued RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (lane 4). *P < .05. (D) Northern blot analysis with the ITS2 probes (see Figure 1D) showing accumulation of 12S pre-rRNA molecules in RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (designated as “–” in the last lane of the left panel) compared with WT cells. This defect is ameliorated in RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs expressing WT RPL5 cDNA, but not in those expressing GFP cDNA (right). The ratios of 17S:12S rRNAs determined by densitometry scanning are shown at the bottom.

RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs exhibit ribosomal defects that are rescued by gene correction. (A) Western blot for RPL5 protein in WT1 and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (first 2 lanes). Gene-corrected and control sublines were generated by introducing WT RPL5 or GFP cDNA, respectively, into the AAVS1 locus of RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (lanes 3 and 4). Ratio of RPL5:actin analyzed by densitometry is shown relative to the WT1 clone, which is assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0. (B) Polysome profiling of RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs and sublines with GFP or WT RPL5 cDNAs integrated into the AAVS1 locus. A polysome profile of a WT iPSC line is shown in Figure 1B. Arrow shows direction of the sucrose gradient from less to more dense. (C) Summary of 3 polysome profiling experiments showing increased ratio of 40S:60S ribosomal subunits in RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs (lanes 2 and 3), compared with WT (lane 1) or RPL5-rescued RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (lane 4). *P < .05. (D) Northern blot analysis with the ITS2 probes (see Figure 1D) showing accumulation of 12S pre-rRNA molecules in RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs (designated as “–” in the last lane of the left panel) compared with WT cells. This defect is ameliorated in RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs expressing WT RPL5 cDNA, but not in those expressing GFP cDNA (right). The ratios of 17S:12S rRNAs determined by densitometry scanning are shown at the bottom.

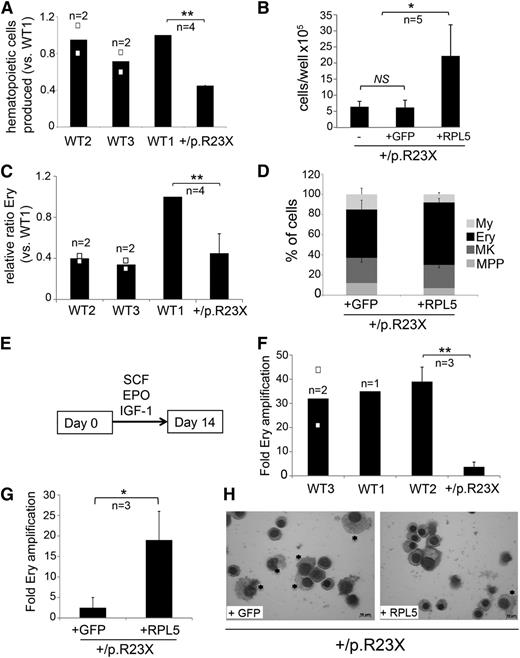

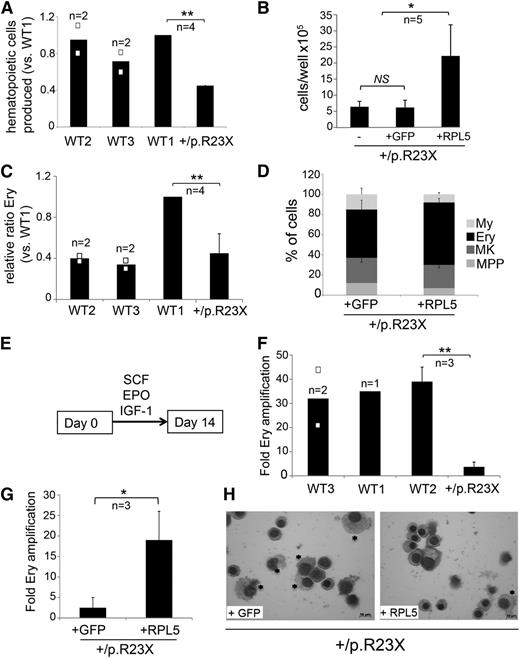

We next compared hematopoietic development by the RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs and genetically rescued sublines. Day 4 EB production of CD31+/KDR+ hematoendothelial progenitors25,26 was normal in RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs (RPL5+/p.R23X and RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP) (data not shown). By day 14 of differentiation, RPL5-haploinsufficient EBs produced ∼50% fewer hematopoietic cells compared with 3 different control cell lines (Figure 7A); this was restored to normal levels after WT RPL5 cDNA correction (Figure 7B). However, there was no specific Ery defect at this time because the relative proportion of CD235+ erythroblasts produced by RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs was within the range exhibited by controls (Figure 7C). The increased proportion of erythroblasts produced by WT1 iPSCs likely reflects clonal variability in Ery potential that we consistently observe between different normal iPSC lines (Figure 7C). In agreement, correction of RPL5 haploinsufficiency in RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs did not significantly increase the proportion of Ery progenitors produced by day 14 EBs (Figure 7D). We next compared the Ery expansion capacity of hematopoietic progenitors produced by day 14 EBs derived from RPL5+/p.R23X and control iPSCs. Equal numbers of progenitors were seeded into medium containing erythropoietin (EPO), stem cell factor (SCF), and insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF1), an Ery-selective cytokine mixture (Figure 7E). After 2 weeks in culture, Ery progenitors from 3 different WT iPSC lines expanded ∼30- to 40-fold, while those derived from RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs expanded only ∼threefold (10- to 12-fold difference, Figure 7F). Using identical methods, Ery progenitors from RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP and RPL5+/p.R23X + RPL5 iPSCs exhibited ∼2.5- and 19-fold expansion, respectively (sevenfold difference, Figure 7G). Morphologic analysis showed that progenitors from RPL5+/p.R23X + RPL5 iPSCs generated predominantly orthochromatic erythroblasts, while a greater proportion of myeloid cells was produced in cultures derived from the RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP line (Figure 7H). Confirming this, flow cytometry showed 80% CD235+ Ery cells in the +RPL5 cultures vs 47% in the +GFP ones. Overall, these findings show that genetic rescue by WT RPL5 at least partially alleviates the expansion defect exhibited by RPL5+/p.R23X iPSC-derived Ery progenitors.

Defective erythropoiesis in RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs is restored by gene correction. (A) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs generated by RPL5+/p.R23X and 3 different WT lines at day 14 of differentiation. Cultures contained roughly equal numbers of EBs that were of similar size. **P < .01; n = 4 independent experiments performed in parallel between WT1 and RPL5+/p.R23X, 2 of them included WT2 and WT3. All the results are shown as a ratio relative to WT1, which was used as an internal standard in every experiment and is assigned an arbitrary value of 1. (B) Hematopoietic cells released by EBs from RPL5+/p.R23X (designated as “–”) and gene-corrected (+GFP control and +RPL5) iPSCs at day 14 of differentiation. Cultures contained roughly equal numbers of EBs that were of similar size. *P < .05. All experiments were performed in parallel. n = 5 independent experiments. (C) Ery cells released by day 14 EBs from RPL5+/p.R23X and WT iPSCs. Results are shown as relative ratio to WT1 present in each experiment and used as an internal standard. RPL5+/p.R23X EBs released fewer Ery cells than WT1 EBs (P < .01, n = 4), but not WT2 or WT3 EBs. The increased proportion of erythroblasts produced by WT1 iPSCs reflects clonal variability in Ery potential that we observe consistently between different WT iPSC lines. (D) Relative frequency (%) of each hematopoietic lineage present in day 14 EB cultures represented in experiment from panel B, as determined by flow cytometry according to Figure 3C. The proportion of Ery cells in WT RPL5-rescued RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs was not significantly increased compared with nonrescued clones; n = 5 independent experiments. (E) Hematopoietic cells (2 × 105) released by 14-day-old EBs from WT and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs were incubated with the Ery cytokine combination EPO, SCF, and IGF-1 and cultured for 14 days. (F) Expansion of iPSC-derived Ery progenitors after 14 days in liquid culture according to the protocol described in panel E. Data are shown for 3 WT control cell lines and the RPL5+/p.R23X clone (**P < .01). (G) Expansion of Ery progenitors derived from RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs with GFP or WT RPL5 cDNAs, assessed according to the strategy described in panels E and F. Correction of RPL5 haploinsufficiency increased Ery expansion by about sevenfold (*P < .05). (H) May Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cells from experiment in panel G at day 14 of culture. The cultures derived from RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP iPSCs express a greater proportion of myeloid cells (*) compared with cultures derived from RPL5+/p.R23X + RPL5 iPSCs, which are predominantly Ery (right panel). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axioskope 2 microscope, Axiocam camera, and AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss). The black bars in the graphs (A,C,F) represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For iPSC lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares.

Defective erythropoiesis in RPL5-haploinsufficient iPSCs is restored by gene correction. (A) Hematopoietic cells released from EBs generated by RPL5+/p.R23X and 3 different WT lines at day 14 of differentiation. Cultures contained roughly equal numbers of EBs that were of similar size. **P < .01; n = 4 independent experiments performed in parallel between WT1 and RPL5+/p.R23X, 2 of them included WT2 and WT3. All the results are shown as a ratio relative to WT1, which was used as an internal standard in every experiment and is assigned an arbitrary value of 1. (B) Hematopoietic cells released by EBs from RPL5+/p.R23X (designated as “–”) and gene-corrected (+GFP control and +RPL5) iPSCs at day 14 of differentiation. Cultures contained roughly equal numbers of EBs that were of similar size. *P < .05. All experiments were performed in parallel. n = 5 independent experiments. (C) Ery cells released by day 14 EBs from RPL5+/p.R23X and WT iPSCs. Results are shown as relative ratio to WT1 present in each experiment and used as an internal standard. RPL5+/p.R23X EBs released fewer Ery cells than WT1 EBs (P < .01, n = 4), but not WT2 or WT3 EBs. The increased proportion of erythroblasts produced by WT1 iPSCs reflects clonal variability in Ery potential that we observe consistently between different WT iPSC lines. (D) Relative frequency (%) of each hematopoietic lineage present in day 14 EB cultures represented in experiment from panel B, as determined by flow cytometry according to Figure 3C. The proportion of Ery cells in WT RPL5-rescued RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs was not significantly increased compared with nonrescued clones; n = 5 independent experiments. (E) Hematopoietic cells (2 × 105) released by 14-day-old EBs from WT and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs were incubated with the Ery cytokine combination EPO, SCF, and IGF-1 and cultured for 14 days. (F) Expansion of iPSC-derived Ery progenitors after 14 days in liquid culture according to the protocol described in panel E. Data are shown for 3 WT control cell lines and the RPL5+/p.R23X clone (**P < .01). (G) Expansion of Ery progenitors derived from RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs with GFP or WT RPL5 cDNAs, assessed according to the strategy described in panels E and F. Correction of RPL5 haploinsufficiency increased Ery expansion by about sevenfold (*P < .05). (H) May Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cells from experiment in panel G at day 14 of culture. The cultures derived from RPL5+/p.R23X + GFP iPSCs express a greater proportion of myeloid cells (*) compared with cultures derived from RPL5+/p.R23X + RPL5 iPSCs, which are predominantly Ery (right panel). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axioskope 2 microscope, Axiocam camera, and AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss). The black bars in the graphs (A,C,F) represent mean values. For iPSC lines examined in 3 or more independent experiments, the error bars show SD. For iPSC lines examined twice, individual data points from each experiment are shown as open squares.

Discussion

DBA has captivated hematologists since the disease was first described >70 years ago.30 New insights arose from discoveries that ∼50% of DBA cases are caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in genes encoding large and small ribosomal protein subunits. However, the pathophysiology of DBA remains incompletely understood, therapy remains suboptimal and there is no experimental system that fully recapitulates the disease. Here, we show that RPS19+/p.Q126X and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs derived from 2 different DBA patients exhibit distinct defects in ribosome biogenesis and hematopoiesis that are reversed upon restored expression of the deficient ribosomal proteins. Our work provides a renewable source of human DBA cells for mechanistic studies and proof of principle for genetic correction of this disorder in human stem cells. In future studies, it should also be possible to use DBA iPSCs to generate biologically relevant cells for drug screening.

Lentiviral vector-mediated reprogramming of RPS19 and RPL5-haploinsufficient fibroblasts was inefficient compared with control cells and for this reason we were able to obtain only 1 stable iPSC clone of each genotype. This may be due to technical issues that are unrelated to DBA defects. For example, the patient fibroblast lines may have been near senescence and therefore difficult to reprogram. Alternatively, DBA fibroblasts may be inherently resistant to reprogramming by the methods used in this study. For example, it is possible that excessive activation of p53 inhibits the generation of DBA iPSCs. In 1 model for DBA pathogenesis, defective ribosome assembly causes buildup of ribosomal protein subunits, some of which sequester the p53 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 (reviewed in Ball1 ). Consequent accumulation of p53 induces cell senescence, which contributes to disease pathology and could also impair reprogramming. Excessive activation of p53 interferes with the formation and maintenance of iPSCs (reviewed in Menendez et al31 ). Of note, low reprogramming efficiency of patient fibroblasts has been described in other inherited disorders associated with activated p53, such as Fanconi anemia,32 and ataxia telangectasia.33 We did not detect increased p53 protein or messenger RNA encoding its target gene p21/CDKN1 in the RPS19+/p.Q126X or RPL5+/p.R23X iPSC lines (not shown). However, this does not exclude a role for p53 activation in the reduced reprogramming frequency of DBA fibroblasts that we observed, as high-expressing clones may have been eliminated. Therefore, further studies are required to determine whether activation of p53 or other consequences of ribosome insufficiency render somatic DBA cells inherently resistant to reprogramming.

As expected, RPL5 and RPS19 mutated iPSCs exhibit distinct abnormalities in ribosome biogenesis affecting the large and small subunits, respectively. RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs expressed reduced RPL5 protein, impaired production of the 60S ribosomal subunit and faulty maturation of 12S pre-rRNA. Similar defects were observed in HeLa or A549 cells after short interfering RNA–mediated RPL5 knockdown and in lymphoblastoid cells from an RPL5-mutated DBA patient.17,34,35 In contrast, RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs expressed normal levels of total cellular RPS19 protein by western blotting, although nuclear RPS19 protein was reduced (see Figure 4C-D). Thus, RPS19 could be limiting in nucleoli, where ribosomes are assembled. Supporting this, RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs exhibited defects in 40S ribosome biogenesis and rRNA processing. These findings show that ribosome biogenesis is impaired in the mutant iPSCs, despite normal whole-cell RPS19 protein and consistent with reports demonstrating ribosome assembly defects with no or small changes in total cellular RPS19 protein in lymphoblastoid cells from DBA patients19 and in RPS19 short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-expressing CD34+ cells.16

Impaired small ribosome subunit assembly and rRNA processing has been observed in HeLa cells after short interfering RNA-mediated RPS19 knockdown and in fibroblasts, lymphocytes, lymphoblastoid cells, and bone marrow cells of RPS19-mutated DBA patients.19,23,36,37 However, DBA patient–derived fibroblasts and immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines exhibit ribosomal defects that are appreciably milder than those observed in the patient-derived iPSCs described here.17,19,36 These differences may reflect increased requirements for ribosomal biogenesis and/or protein synthesis in iPSCs, which exhibit high proliferative and metabolic rates and perhaps unique ribosomal requirements. It is also possible that ribosome biogenesis varies in different cell types and tissues, causing unique sensitivities to ribosomal stresses. These findings support the concept that different tissues exhibit variable demands for ribosome biogenesis and distinct set points for manifesting associated defects. Such parameters should be better defined through directed differentiation of DBA iPSCs into various non-hematopoietic tissues of interest.

The hematopoietic defects exhibited by RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs most strongly affect the Ery lineage, in agreement with previous studies of primary cells from DBA patients,14-16 RPS19-knockdown experiments,13,38 and animal models.3,8,10 We also observed impaired production of myeloid and megakaryocytic lineages in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs, although these effects were less severe than for the Ery lineage. These findings are consistent with pancytopenia and multilineage bone marrow hypoplasia exhibited by some DBA patients, particularly older ones who are steroid refractory (Giri et al39 ; M.B., unpublished observations). In vivo shRNA-mediated suppression of RPS19 in mice also induces progressive bone marrow failure.10 Reduced myelopoiesis in cultured cells from DBA patients has been observed,40,41 although not consistently.42 The extent to which DBA affects different hematopoietic lineages in patients and experimental models probably depends on the magnitude of ribosomal protein insufficiency, genetic modifiers, species effects, in vitro culture conditions, and hematopoietic demands in vivo. The clinical and laboratory manifestations of DBA indicate that Ery cells are particularly sensitive to ribosomal protein insufficiency, perhaps in part due to stresses associated with massive heme synthesis.43 In cultured human CD34+ cells, erythropoiesis was selectively inhibited by relatively mild shRNA knockdown of RPS19 while more effective shRNAs also reduced myelopoiesis.12 In bone marrow–derived cells from a RPS19-mutated DBA patient, rRNA processing was more severely affected in more mature CD34− cells compared with the immature CD34+ fraction, reflecting varying requirements for RPS19 in different cell types and stages of maturation.23 The marked ribosome dysfunction that we observed in RPS19+/p.Q126X iPSCs may contribute to the relatively profound panhematopoietic defect observed when this clone was driven to differentiation.

Of note, the in vitro differentiation protocols used in the current study most closely recapitulate early yolk sac (primitive-type) erythropoiesis, as reflected by the production of embryonic globins ε and ζ.25 While it is also possible to differentiate iPSCs/ESCs into later-stage Ery progenitors expressing γ and some β globins, these approaches are generally less efficient and more difficult to quantify. Regardless, our findings suggest that ribosomal insufficiency caused by DBA could impair hematopoiesis prenatally. Similarly, several zebrafish models for DBA exhibit defects in primitive erythropoiesis.8,9,11 In humans, DBA is known to present as fetal hydrops (reviewed in Dunbar et al44 ). The current study indicates that DBA can affect the first wave of erythropoiesis to arise in the embryo, which in severe instances, could result in early spontaneous abortion.

The efficiency of hematopoiesis varies between different WT ESC and iPSC clones,28 which can interfere with evaluating genotype-phenotype correlations and creating disease models. Several lines of evidence indicate that the hematopoietic defects exhibited by our DBA patient–derived iPSCs are due to mutations in ribosomal protein genes and not caused by clonal variation or irrelevant mutations acquired during reprogramming. First, the hematopoietic abnormalities observed in RPS19+/p.Q126X and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSCs are consistent with those observed in patients and other experimental models for DBA. Second, impaired ribosome biogenesis occurs concomitant with defective hematopoiesis in the mutant iPSC lines. Finally, ribosome synthesis and hematopoietic potential are simultaneously corrected upon genetic rescue of the ribosomal protein mutations. Similarly, retroviral transduction of RPS19 cDNA into RPS19-mutated hematopoietic progenitors from DBA patients enhances erythropoiesis in vitro and in vivo but has minimal effects on the development of blood progenitors from normal individuals.42,45 These observations indicate that RPS19+/p.Q126X and RPL5+/p.R23X iPSC clones analyzed concurrently with their isogenic gene-corrected derivatives provide accurate, biologically relevant models for 2 types of DBA.

We genetically rescued the DBA iPSCs by using zinc finger nuclease-mediated homologous recombination29 to introduce cDNAs encoding the defective ribosomal proteins (or control GFP cDNA) into intron 1 of the AAVS1 locus, a preferential integration site of adeno-associated virus. This locus is considered to be a “safe harbor” in which integrated transgenes are expressed stably without epigenetic silencing and produce minimal effects on surrounding genes.29,46 This approach has been used to correct gene defects in several disease models including murine hemophilia B47 and iPSCs from patients with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease.48 This strategy could eventually be used to produce autologous, gene-corrected cells for hematopoietic cell replacement therapy in DBA and other blood disorders. One potential problem is that constitutive expression of the defective gene could result in supraphysiologic levels of the corresponding protein that are potentially toxic. However, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells contain endogenous mechanisms to balance ribosome synthesis by degrading excess ribosomal protein subunits.49,50 In agreement, overexpression of epitope-tagged RPS19 in 293T cells induced marked downregulation of endogenous RPS19 (supplemental Figure 2). More importantly, gene correction of RPS19 or RPL5 mutant DBA cells improved ribosome assembly and hematopoiesis without toxicity or excessive accumulation of the corresponding ribosomal proteins (see Figures 4-7).

In summary, we show that patient-derived iPSCs recapitulate the hematopoietic abnormalities of DBA and are amenable to genetic correction. These lines represent new tools in which to investigate how ribosomal insufficiency contributes to DBA pathophysiologies and potential platforms for therapeutic discovery. It should also be possible to study nonhematopoietic abnormalities of DBA by differentiating the mutant iPSCs into cell types that influence the development of affected tissues including heart, limbs, and urogenital tract.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Darrell Kotton and Gustavo Mostoslavsky for providing the STEMCCA reprogramming vectors.

This work was supported by US Department of Defense grant BM090168 (M.J.W., P.J.M., and M.B.), National Institutes of Health grants RC2 HL101606 (M.J.W.) and P30DK090969 (M.J.W.), and National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health grants 2R01CA106995 (P.J.M.) and 2R01 CA105312 (M.B.) and the Jane Fishman Grinberg endowed chair for stem cell research (M.J.W.). The project was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources grant UL1RR024134, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000003.

Authorship

Contribution: L.G., J.G., S.H.M., J.A.M., S.P., L.M.S., and M.A. designed and performed experiments; L.G., P.G., P.J.M., M.B., D.L.F., and M.J.W. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; and G.M.P. designed the human subjects research aspects of the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mitchell J. Weiss, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Room 316B AR, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: weissmi@e-mail.chop.edu.

References

Author notes

L.G. and J.G. contributed equally to this work.