Key Points

PML-RARA and AML1-ETO evade NK cell recognition by specifically downregulating the expression of CD48.

The findings are relevant to AML patients bearing these specific translocations.

Abstract

PML-RARA and AML1-ETO are important oncogenic fusion proteins that play a central role in transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Whether these fusion proteins render the tumor cells with immune evasion properties is unknown. Here we show that both oncogenic proteins specifically downregulate the expression of CD48, a ligand of the natural killer (NK) cell activating receptor 2B4, thereby leading to decreased killing by NK cells. We demonstrate that this process is histone deacetylase (HDAC)-dependent, that it is mediated through the downregulation of CD48 messenger RNA, and that treatment with HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) restores the expression of CD48. Furthermore, by using chromatin immuoprecepitation (ChIP) experiments, we show that AML1-ETO directly interacts with CD48. Finally, we show that AML patients who are carrying these specific translocations have low expression of CD48.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults.1 There are several types of AML (approximately 30%) that are characterized by chromosomal translocations, which generate oncogenic fusion proteins.2 Two of the most common translocations in AML are t(15:17), which gives rise to the fusion protein PML-RARA, and t(8:21), which generates the fusion protein RUNX1-RUNX1T1 (AML1-ETO).3,4 Although these fusion proteins were discovered more than 20 years ago,5,6 it is not known whether they provide immune evasion properties to AML tumors.

Over the past few decades it has been established that natural killer (NK) cells, which are part of the innate immune system, play an important role in killing cancerous cells,7,8 and specifically AML cells.9,10 Several studies have found that AML patients who received transplants from NK alloreactive donors had lower relapse rates and improved disease-free survival.11-13 Furthermore, it was recently reported that the presence of the NK cell receptor KIR2DS1, in matched unrelated donors, is associated with distinct outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in AML patients.14 Finally, it was shown in several studies that NK cell activity correlates with clinical parameters of AML patients.15,16

Killing by NK cells is mediated by several killer receptors that recognize distinct ligands.17-24 Several human killer receptors, such as NKp44 and NKp30, have no mouse orthologs, and others, such as 2B4, have a mouse ortholog protein with opposing functions. In humans, 2B4 functions as an activating receptor,25-27 whereas in mice, it mainly functions as an inhibitory receptor.28,29 However, in both cases it recognizes CD48.25-28

Despite the crucial role played by NK cells in eliminating AML tumors, the NK cell recognition of AML tumor cells is impaired at several levels (reviewed in Lion et al30 ). However, the mechanisms leading to the resistance of AML cells to NK cell killing are unclear, and it is also unknown whether the AML fusion proteins specifically provide immune resistance to AML cells.

Methods

Cloning, viral transduction, and patient samples

All genes were cloned into the DsRED lentiviral vector. Details of the cloning procedure and the list of primers used for cloning are included in the supplemental Methods on the Blood Web site. Lentiviral virions were produced by transient three-plasmid transfection: 293T cells were cotransfected with the lentiviral vector, a plasmid encoding the lentiviral Gag/Pol, and a plasmid encoding VSV-G at a 10:6.5:3.5 ratios, respectively. Supernatants with the viral particles were collected after 48 hours. These viruses were used to transduce U937 cells in the presence of polybrene. The collection of patient samples was approved by the institutional Helsinki Committee of Hadassah Medical Center. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Drugs

We used the following histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (HDACis): Trichostatin A (TSA) (Alexis Biochemicals) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a final concentration of 100 ng/mL for 18 hours, as previously described31 ; mocetinostat (MGCD0103, catalog #S1122, Selleck Chemicals) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a final concentration of 1 µM for 18 to 24 hours, as previously described32 ; valproic acid (P4543, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in water at a final concentration of 5 mM for 24 hours; entinostat (MS-275, catalog #27011; BPS Bioscience) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a final concentration of 1 µM for 18 to 24 hours, as previously described.32 We also used all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) (retinoic acid, catalog #R2625; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a final concentration of 10 µM for 72 hours.

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxic activity of NK cells against various targets was assessed in 5-hour 35S-release assays, as previously described.33 The final concentration of the blocking antibodies was 0.5 μg/well. We used the blocking antibody anti-CD48 (sc-8397; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As control antibodies we used the anti-CD99 monoclonal antibody and the anti-HA monoclonal antibody. For the redirected lysis experiment target p815 cells were preincubated for 1 hour on ice with 0.1 μg/well of the indicated antibodies.

The qRT-PCR

Details of the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) procedure and the list of primers are included in the supplemental Methods.

ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed as previously described.34 We used the following antibodies: anti-HA (SC-805; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-ETO (SC-9737; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti–AML1-ETO (C15310197; Diagenode). Precipitated DNA was subjected to qRT-PCR analysis using gene-specific primer pairs. The list of primers used for ChIP is included in the supplemental Methods.

Bioinformatic analysis

RUNX1 (AML1) binding sites were identified by the program “Match” at BIOBASE site (http://www.gene-regulation.com/cgi-bin/pub/programs/match/bin/match.cgi), as well as by the JASPAR database (http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/).35 We included only sites that were identified by both sources.

Results

Overexpression of AML fusion proteins leads to decreased killing by NK cells

To study whether the expression of the AML fusion proteins would affect NK cell cytotoxicity, we cloned the oncogenic fusion proteins PML-RARA and AML1-ETO into lentiviral vectors, and stably transduced U937 cells with these viruses or with a control virus. We used the monocytic cell line U93736 because these cells are commonly used for expressing these oncogenic proteins.37,38 In agreement with previous studies,39 expression of the AML fusion proteins in several other cell lines (eg, RKO, L363, BJAB, Jurkat, and MRC-5), as well as in primary fibroblasts, was unsuccessful, leading to either cell apoptosis or selected growth of clones that were negative for the expression of the fusion proteins (data not shown).

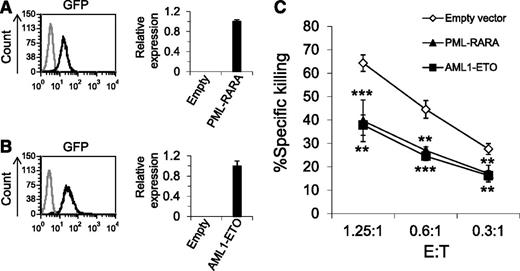

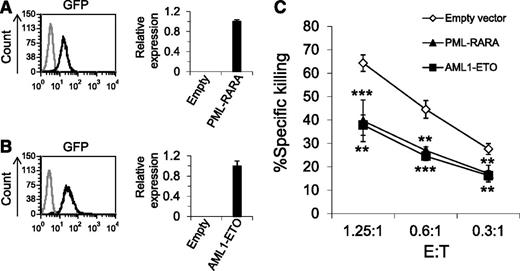

The lentiviral vectors we used to introduce the AML fusion proteins contained green fluorescent protein (GFP), thus we could determine the transduction efficiency of the fusion proteins, which was very high (Figure 1A-B, left histograms). The qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that both PML-RARA and AML1-ETO proteins were expressed in the transduced cells (Figure 1A-B, right graphs).

Overexpression of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO leads to decreased killing by NK cells. (A-B) Left: GFP expression in U937 cells transduced with a lentivirus encoding for GFP together with PML-RARA or AML1-ETO (A-B, black lines, respectively) compared with naïve U937 cells (gray line). Right: The qRT-PCR analysis with specific primers for PML-RARA (A) and AML1-ETO (B). The results were normalized to hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) and the relative copy number of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO was arbitrarily defined as 1. The figure shows 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. (C) 35S-labeled U937 cells expressing PML-RARA, AML1-ETO, or an empty vector were incubated with primary NK cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. **P < .01; ***P < .001, Student t test. The upper asterisks are for PML-RARA and the lower asterisks are for AML1-ETO. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicates. One of 10 representative experiments performed is shown.

Overexpression of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO leads to decreased killing by NK cells. (A-B) Left: GFP expression in U937 cells transduced with a lentivirus encoding for GFP together with PML-RARA or AML1-ETO (A-B, black lines, respectively) compared with naïve U937 cells (gray line). Right: The qRT-PCR analysis with specific primers for PML-RARA (A) and AML1-ETO (B). The results were normalized to hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) and the relative copy number of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO was arbitrarily defined as 1. The figure shows 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. (C) 35S-labeled U937 cells expressing PML-RARA, AML1-ETO, or an empty vector were incubated with primary NK cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. **P < .01; ***P < .001, Student t test. The upper asterisks are for PML-RARA and the lower asterisks are for AML1-ETO. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicates. One of 10 representative experiments performed is shown.

Because previous studies demonstrated that NK cells play an important role in AML,9,11,15 next, we tested whether the oncogenic AML fusion proteins will affect the killing of the transduced cells by NK cells (Figure 1C). These experiments demonstrated that the killing of cells expressing either PML-RARA or AML1-ETO was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing an empty vector.

The AML oncogenic proteins downregulate the expression of CD48 leading to reduced NK cell cytotoxicity

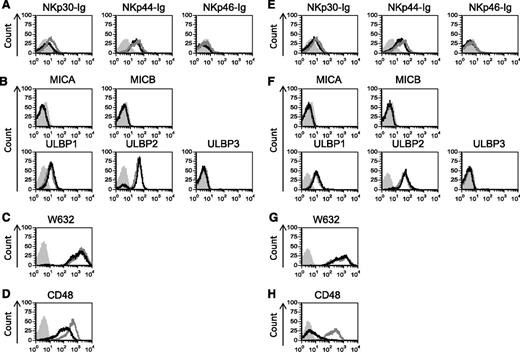

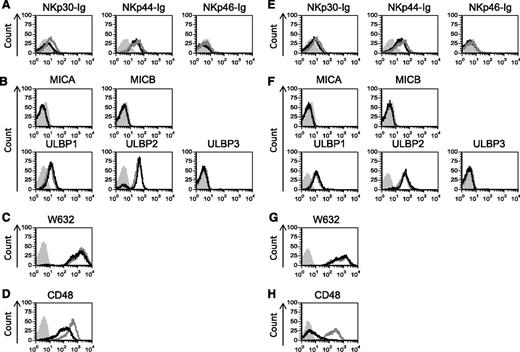

Next, we analyzed the expression of different NK cell ligands in cells expressing PML-RARA (Figure 2A-D) or AML1-ETO (Figure 2E-H) by using flow cytometry. Because the identity of some of the NCR ligands is unknown, we detected the expression of the NCR ligands by using chimeric fusion proteins composed of the extracellular portion of NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 fused to the Fc portion of human IgG1. Staining of the NK cell ligands revealed little or no change in the expression of any of the NCR ligands, the NKG2D ligands or the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I proteins (Figure 2). However, a significant and specific decrease in CD48 expression was observed in cells expressing the oncogenic proteins (Figure 2D,H).

CD48 is specifically downregulatred by PML-RARA and AML1-ETO. (A-H) Flow cytometry analysis of various NK cell ligands expressed by U937 cells transduced with the 2 AML oncogenes: PML-RARA (A-D, black lines) or AML1-ETO (E-H, black lines) compared with U937 cells transduced with an empty vector (A-H, gray lines). Gray shaded histograms, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One of at least 2 representative experiments performed (the staining of CD48 was repeated 8 times, the staining of ULBP1 and ULBP2 was repeated 3 times) is shown.

CD48 is specifically downregulatred by PML-RARA and AML1-ETO. (A-H) Flow cytometry analysis of various NK cell ligands expressed by U937 cells transduced with the 2 AML oncogenes: PML-RARA (A-D, black lines) or AML1-ETO (E-H, black lines) compared with U937 cells transduced with an empty vector (A-H, gray lines). Gray shaded histograms, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One of at least 2 representative experiments performed (the staining of CD48 was repeated 8 times, the staining of ULBP1 and ULBP2 was repeated 3 times) is shown.

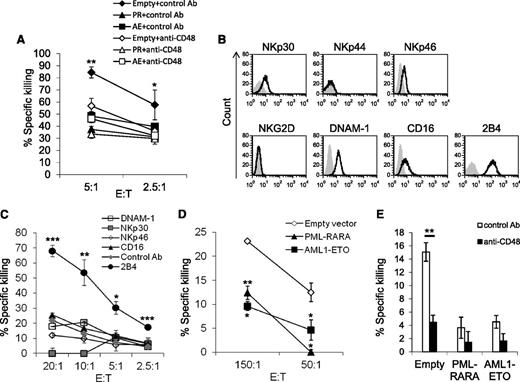

To test whether the reduced expression of CD48 will result in reduced 2B4-mediated killing, we performed NK cytotoxicity assays using cells expressing the oncogenic proteins or a control vector (empty) in the presence or in the absence of a blocking anti-CD48 antibody or a control monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Figure 3A). Blocking of CD48 significantly reduced the killing of cells expressing the control vector, whereas blocking with a control mAb had no effect. Because blocking of CD48 reduced the killing of all targets to a similar level, we concluded that the AML fusion proteins affect NK cell cytotoxicity primarily by targeting the CD48-2B4 axis.

The downregulation of CD48 results in reduced NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) 35S-labeled target cells expressing either the AML oncogenic proteins or an empty vector were incubated with an anti-CD48 antibody or an anti-CD99 antibody (used as a control) and then incubated with primary NK cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of activating NK cell receptors expressed by the human NK cell line YTS eco (black empty histograms). Gray shaded histogram, background staining with the secondary-conjugated antibody only. (C) The 35S-labeled P815 cells, coated with different antibodies (indicated as:anti-CD16, NKp30, NKp46, 2B4, DNAM-1, and anti-hemagglutinin antibody, as a control antibody), were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated E:T ratios. (D) The 35S-labeled U937 cells expressing PML-RARA, AML1-ETO, or an empty vector were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated E:T ratios. (E) The 35S-labeled target cells expressing either the AML oncogenes or an empty vector were incubated with an anti-CD48 antibody or with an anti-hemagglutinin antibody (used as a control) and then incubated with YTS eco cells (E:T 50:1). One of 2 killing experiments performed is shown.(A-E) *P < .05: **P < .01, ***P < .001, Student t test.

The downregulation of CD48 results in reduced NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) 35S-labeled target cells expressing either the AML oncogenic proteins or an empty vector were incubated with an anti-CD48 antibody or an anti-CD99 antibody (used as a control) and then incubated with primary NK cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of activating NK cell receptors expressed by the human NK cell line YTS eco (black empty histograms). Gray shaded histogram, background staining with the secondary-conjugated antibody only. (C) The 35S-labeled P815 cells, coated with different antibodies (indicated as:anti-CD16, NKp30, NKp46, 2B4, DNAM-1, and anti-hemagglutinin antibody, as a control antibody), were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated E:T ratios. (D) The 35S-labeled U937 cells expressing PML-RARA, AML1-ETO, or an empty vector were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated E:T ratios. (E) The 35S-labeled target cells expressing either the AML oncogenes or an empty vector were incubated with an anti-CD48 antibody or with an anti-hemagglutinin antibody (used as a control) and then incubated with YTS eco cells (E:T 50:1). One of 2 killing experiments performed is shown.(A-E) *P < .05: **P < .01, ***P < .001, Student t test.

To further corroborate these observations, we used the NK cell line YTS eco, which is known to kill target cells mainly via its 2B4 receptor.26 Indeed, although YTS cells express activating receptors other than 2B4, such as NKp30, NKp46, DNAM-1, and CD16 (Figure 3B), we show that only the 2B4 receptor is functional by performing a redirected killing assay (an assay used to determine the functional activity of a particular receptor40 (Figure 3C). Next, YTS cells were incubated with U937 cells expressing an empty vector or a vector expressing each of the 2 AML oncogenic proteins. To be able to obtain killing of U937 cells by YTS cells, we had to use high E:T ratios because at lower E:T ratios there was no killing observed. This is probably because of the relatively low expression of CD48 in U937 cells. Indeed, as can be seen in supplemental Figure 1, efficient killing by YTS cells is tightly correlated with CD48 expression. Therefore, YTS cells do not accurately reflect the activity of primary NK cells. However, despite these limitations, we used YTS cells to verify our findings in an isolated 2B4-CD48 system.

As shown above with primary NK cells (Figures 1C and 3A), the cells expressing PML-RARA or AML1-ETO were killed less efficiently by YTS cells as compared with the control cells (Figure 3D), and after the blocking of CD48, all cells were killed to a similar extent (Figure 3E). The killing of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO–expressing cells by YTS cells was almost undetectable (Figure 3E) because the expression of CD48 was reduced in these cells (Figure 2D,H), rendering these cells insensitive for killing by YTS cells (as explained above, the expression level of CD48 is critical for activation of YTS cells [supplemental Figure 1]).

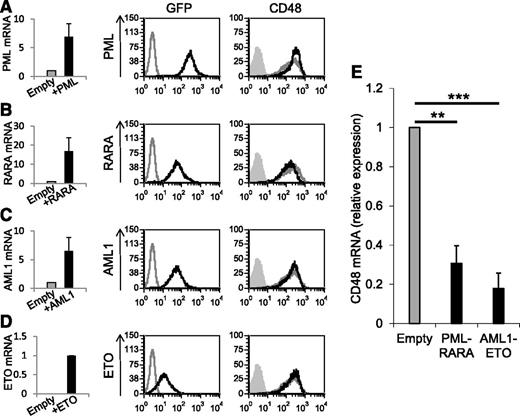

The AML fusion proteins reduce the mRNA levels of CD48

To investigate the mechanisms by which PML-RARA and AML1-ETO downregulate CD48, we first tested whether each of the single proteins composing the fusion proteins would also reduce the expression of CD48. We cloned the single proteins PML3, RARA, AML1b, and ETO into lentiviral vectors (expressing GFP), transduced them into U937 cells, and verified the overexpression of these proteins by qRT-PCR (Figure 4A-D, left graphs) and by monitoring the GFP levels in the transduced cells (Figure 4A-D, left histograms, labeled GFP). As it can be seen, the expression of CD48 was not decreased by any of the single proteins tested (Figure 4A-D, right histograms, labeled CD48). To further investigate the mechanisms leading to the downregulation of CD48 by the AML fusion proteins, we analyzed the messenger RNA (mRNA) level of CD48 in cells expressing the oncogenic proteins by qRT-PCR. We observed that the mRNA level of CD48 was significantly reduced in the presence of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO (Figure 4E).

Expression of the oncogenic AML proteins leads to reduced CD48 mRNA levels. (A-D) qRT-PCR and FACS analysis of U937 cells transduced with PML3 (A), RARA (B), AML1b (C), and ETO (D). Left graphs: Verification of the overexpression of the single proteins by qRT-PCR. The results were normalized to hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments (each in triplicates). Left histograms (labeled GFP): Flow cytometry of GFP expression (indicative of the transduction) of untransduced U937 cells (gray line) and transduced cells (black line). Right histograms (labeled CD48): Flow cytometry analysis of CD48 expression in cells transduced with 1 of the single proteins (black line) or with an empty vector (gray line). The gray shaded histograms are the background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. The FACS staining includes 1 representative experiment of 2 representative experiments performed. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of CD48 in U937 cells transduced with an empty vector compared with U937 transduced with PML-RARA or AML1-ETO. The results were normalized to the expression of HPRT. The relative copy number of CD48 in cells expressing the empty vector was defined as 1. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments (each in triplicates). **P < .01; ***P < .001, Student t test.

Expression of the oncogenic AML proteins leads to reduced CD48 mRNA levels. (A-D) qRT-PCR and FACS analysis of U937 cells transduced with PML3 (A), RARA (B), AML1b (C), and ETO (D). Left graphs: Verification of the overexpression of the single proteins by qRT-PCR. The results were normalized to hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments (each in triplicates). Left histograms (labeled GFP): Flow cytometry of GFP expression (indicative of the transduction) of untransduced U937 cells (gray line) and transduced cells (black line). Right histograms (labeled CD48): Flow cytometry analysis of CD48 expression in cells transduced with 1 of the single proteins (black line) or with an empty vector (gray line). The gray shaded histograms are the background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. The FACS staining includes 1 representative experiment of 2 representative experiments performed. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of CD48 in U937 cells transduced with an empty vector compared with U937 transduced with PML-RARA or AML1-ETO. The results were normalized to the expression of HPRT. The relative copy number of CD48 in cells expressing the empty vector was defined as 1. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments (each in triplicates). **P < .01; ***P < .001, Student t test.

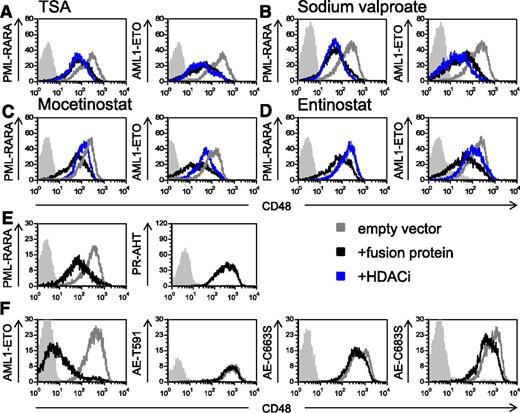

The downregulation of CD48 by the oncogenic proteins is mediated by HDAC

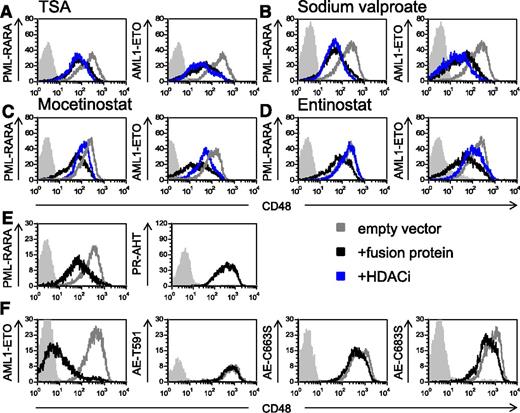

Because it has been well established that PML-RARA and AML1-ETO recruit HDAC,41,42 we tested whether treatment with HDACi could reverse the downregulation of CD48. We initially tested the effect of the pan-HDACi TSA43 and observed that it did not affect the expression of CD48 (Figure 5A). Similar results were obtained with the HDACi sodium valproate (Figure 5B). Because previous studies demonstrated that both PML-RARA and AML1-ETO recruit class I HDACs,44,45 next we tested the effect of the specific class I HDACi,43,46 mocetinostat (MGCD0103), and entinostat (MS-275) on CD48 expression. Both medications specifically inhibit the class I HDACs, HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3.43,46 We observed that treatment with both class I HDACi increased significantly the level of CD48 (Figure 5C-D and supplemental Figure 2A). We have also tested the effect of ATRA, which is part of the standard treatment in AML associated with PML-RARA.47 We observed that treatment with ATRA did not increase the expression of CD48 both in the U937 transfected cells (supplemental Figure 3A) or in cells, which endogenously express the fusion proteins (NB4 and Kasumi-1) (supplemental Figure 3B).

The downregulation of CD48 by the AML fusion oncogenes is HDAC-dependent. (A-D) Flow cytometry analysis of CD48 expression in U937 cells transduced with the AML oncogenic proteins (indicated in the y-axis of the histograms). Cells were treated with either solvent control (black lines) or 4 different HDACi (indicated above the histograms, blue lines): TSA (A), sodium valproate (B), mocetinostat (C), and entinostat (D). The gray line represents the CD48 staining of U937 cells transduced with an empty vector. Gray shaded histogram, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One representative experiment of at least 3 representative experiments performed is shown. (E and F) FACS analysis of CD48 expression without mutations (left histograms) or with mutations (right histograms) in the HDAC binding site (the specific mutation is indicated in the y-axis). Mutations were performed in (E) PML-RARA– and in (F) AML1-ETO–expressing cells. The expression of CD48 is compared between the GFP+ cells (black histograms) and the nontransduced cells (gray histograms) because not all cells were trandscuded (see supplemental Figure 4). Gray shaded histogram, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One of 3 representative experiments is shown.

The downregulation of CD48 by the AML fusion oncogenes is HDAC-dependent. (A-D) Flow cytometry analysis of CD48 expression in U937 cells transduced with the AML oncogenic proteins (indicated in the y-axis of the histograms). Cells were treated with either solvent control (black lines) or 4 different HDACi (indicated above the histograms, blue lines): TSA (A), sodium valproate (B), mocetinostat (C), and entinostat (D). The gray line represents the CD48 staining of U937 cells transduced with an empty vector. Gray shaded histogram, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One representative experiment of at least 3 representative experiments performed is shown. (E and F) FACS analysis of CD48 expression without mutations (left histograms) or with mutations (right histograms) in the HDAC binding site (the specific mutation is indicated in the y-axis). Mutations were performed in (E) PML-RARA– and in (F) AML1-ETO–expressing cells. The expression of CD48 is compared between the GFP+ cells (black histograms) and the nontransduced cells (gray histograms) because not all cells were trandscuded (see supplemental Figure 4). Gray shaded histogram, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. One of 3 representative experiments is shown.

To directly demonstrate that HDAC recruitment by the AML fusion proteins is responsible for the downregulation of CD48, we mutated the HDAC binding site of PML-RARA and AML1-ETO. It was previously demonstrated that a triple point mutation in PML -RARA (PR-AHT) is sufficient to abolish its binding to the nuclear receptor corepressor-HDAC complex.41 Regarding AML1-ETO, it was shown that truncation of ETO at amino acid 416 and point mutations of ETO at amino acids 488 and 508 abolished the capability of the ETO protein to bind the nuclear receptor corepressor-HDAC complex42 (these mutations, which were originally described in the ETO protein, correspond to amino acids 591, 663, and 683 in the AML1-ETO fusion protein). Therefore, we introduced all of the above-mentioned mutations into the appropriate AML fusion proteins and cloned all 4 proteins into lentiviral vectors expressing GFP. We verified the transduction efficiency of the mutated proteins by measuring the GFP levels in the transduced cells (supplemental Figure 4), and we analyzed the expression of CD48 by flow cytometry (gated on GFP+ cells). Because not all cells expressed the mutated fusion proteins (supplemental Figure 4), we had an internal control for each of the mutations. Therefore, we were able to compare the expression of CD48 in cells that were growing in the exact same conditions, in the presence of the mutated proteins (GFP+ cells) and in their absence (GFP− cells). As can be seen, in the presence of the mutated AML fusion proteins, CD48 was not downregulated (Figure 5E-F, right histograms). In contrast, and in agreement with the above results, the nonmutated oncogenic proteins reduced CD48 expression (Figure 5E-F, left histograms). Taken together, we concluded that the downregulation of CD48 by PML-RARA and AML1-ETO depends on the recruitment of HDAC by these proteins, and that class I HDACi can reverse this effect.

Regulation of CD48 in cell lines that endogenously express the fusion proteins

Because all of the above experiments were conducted in a single cell line, we wanted to further strengthen our observations by examining the regulation of CD48 in cell lines that endogenously express these AML fusion proteins. Two such common cell lines are NB4 and Kasumi-1, which express the PML-RARA and the AML1-ETO proteins, respectively.48,49

In agreement with our findings, according to a recently published microarray data (NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number: GSE23730), the expression of CD48 increased significantly after knockdown of AML1-ETO in Kasumi-1 cells (Ben-Ami et al50 ) (supplemental Figure 5). As far as we know, gene expression profile analysis after the knockdown of PML-RARA was not performed, probably because such knockdown is toxic to the cells.51,52

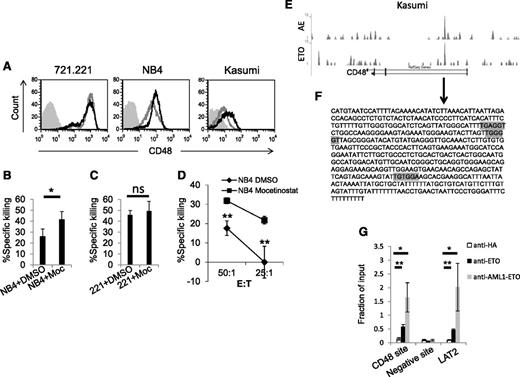

Next we tested whether the AML fusion proteins also control the expression of CD48 via HDACs in cells that endogenously express the fusion proteins. Therefore, we treated Kasumi-1 and NB4 cells with mocetinostat, and as a control, we used the human 721.221 cells (human EBV-transformed B cell line) that express CD48 but do not express the AML fusion proteins. As can be seen in Figure 6A, treatment with mocetinostat increased the expression of CD48 in the NB4 and Kasumi-1 cell lines, but not in the control 721.221 cells. Similar results were obtained with the HDACi entinostat, and with both medications the effect on CD48 expression was statistically significant (supplemental Figure 2B). Subsequently, we proceeded to test whether the upregulation of CD48 after HDACi treatment was functional. We were not able to perform cytotoxicity assays in Kasumi-1 cells, due to the tendency of these cells to undergo apoptosis after treatment with HDACi. Therefore, the following experiments were conducted in NB4 cells only. Treatment of NB4 cells with mocetinostat resulted in increased killing by primary NK cells (Figure 6B). In contrast, no change in the killing of the control 721.221 cells was observed (Figure 6C). Similarly, increased killing of the NB4 cells treated with mocetinostat was observed with YTS eco cells (Figure 6D).

The HDACi mocetinostat increases the endogenous expression of CD48 and NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) Flow cytomery analysis of CD48 expression in 721.221 (left), NB4 (middle), and Kasumi-1 (right) cells treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (gray line) or with the HDACi mocetinostat (Moc) (black line). Gray shaded histograms, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. (B-D) 35S-labeled NB4 (B) or 721.221 cells (C) were treated with DMSO or with the HDACi Moc and incubated with primary NK cells (E:T 20:1 for 721.221 cells and E:T 10:1 for NB4). (D) 35S-labeled NB4 cells, which were treated with DMSO or with the HDACi Moc, were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. All killing experiments were repeated twice. (E) ChIP-seq data obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE23730, of Kasumi-1 cells immunoprecipitated with an AML1-ETO antibody (upper graph labeled AE) or with an ETO antibody (lower graph labeled ETO). Binding sites at the CD48 gene are shown through the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). (F) A sequence of the CD48 intron (arrow) is predicted to be targeted by AML1-ETO based on the ChIP-seq data. Possible binding sites of AML1 are marked by a gray color. (G) Kasumi-1 cells were subjected to ChIP with anti-ETO, anti-AML1-ETO, or control HA antibodies. After precipitation, qRT-PCR assays were performed with primers that specifically amplify the putative AML1-ETO–binding site (CD48 site), a control binding site (negative site), and an identified target of AML1-ETO as a positive control (LAT2). ChiP values are presented as a fraction of the input. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01, Student t test. ns, not significant.

The HDACi mocetinostat increases the endogenous expression of CD48 and NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) Flow cytomery analysis of CD48 expression in 721.221 (left), NB4 (middle), and Kasumi-1 (right) cells treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (gray line) or with the HDACi mocetinostat (Moc) (black line). Gray shaded histograms, background staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. (B-D) 35S-labeled NB4 (B) or 721.221 cells (C) were treated with DMSO or with the HDACi Moc and incubated with primary NK cells (E:T 20:1 for 721.221 cells and E:T 10:1 for NB4). (D) 35S-labeled NB4 cells, which were treated with DMSO or with the HDACi Moc, were incubated with YTS eco cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. All killing experiments were repeated twice. (E) ChIP-seq data obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE23730, of Kasumi-1 cells immunoprecipitated with an AML1-ETO antibody (upper graph labeled AE) or with an ETO antibody (lower graph labeled ETO). Binding sites at the CD48 gene are shown through the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). (F) A sequence of the CD48 intron (arrow) is predicted to be targeted by AML1-ETO based on the ChIP-seq data. Possible binding sites of AML1 are marked by a gray color. (G) Kasumi-1 cells were subjected to ChIP with anti-ETO, anti-AML1-ETO, or control HA antibodies. After precipitation, qRT-PCR assays were performed with primers that specifically amplify the putative AML1-ETO–binding site (CD48 site), a control binding site (negative site), and an identified target of AML1-ETO as a positive control (LAT2). ChiP values are presented as a fraction of the input. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the means of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01, Student t test. ns, not significant.

To study whether the AML fusion proteins directly regulate CD48 expression, we analyzed publicly available databases of 2 genome-wide studies that used ChIP followed by ChIP high throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) to identify hundreds of putative targets of the AML fusion proteins.53,54 Supporting our findings, we observed that AML1-ETO in Kasumi-1 cells seem to have a binding site in the CD48 gene, implying that this fusion protein represses the transcription of this gene by direct binding (Figure 6E and Martens et al53 ). A similar ChIP-seq experiment was performed with PML-RARA in NB4 cells.54 However, only relatively weak binding sites in the CD48 gene were noticed, suggesting that the PML-RARA fusion protein might not affect CD48 expression directly. We therefore continued our investigation only with AML1-ETO in Kasumi-1 cells.

We initially analyzed the sequence to which AML1-ETO binds to in the first intron of CD48 (marked with an arrow below Figure 6E and shown in Figure 6F). Based on two bioinformatic databases, we discovered few binding motifs of RUNX1 (AML1) in this sequence (Figure 6F, gray colored). Next, to verify the direct binding of AML1-ETO to the CD48 gene, we performed ChIP experiments in Kasumi-1 cells with two different antibodies directed to the fusion protein (against ETO or specifically against AML1-ETO) and with a control antibody. The immunoprecipitates were quantified by qRT-PCR with specific primers for three gene regions: the expected binding site at the CD48 gene (Figure 6F), an unrelated site in the CD48 gene (as a negative control), and the binding site of a known target of AML1-ETO, LAT2.32 Importantly, the predicted sequence of the binding site of AML1-ETO in the CD48 gene, as well as LAT2, were significantly enriched both with the anti-ETO and the anti-AML1-ETO antibodies compared with the control anti-HA mAb and to the unrelated site (Figure 6G). These experiments verify that indeed, AML1-ETO binds directly to the CD48 gene.

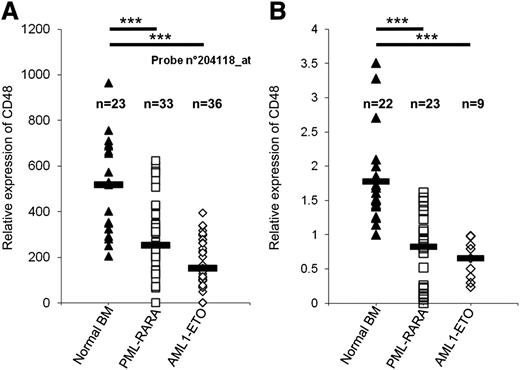

CD48 expression is downregulated in AML patients expressing the fusion proteins

To investigate whether our findings are relevant to human patients, we analyzed the expression of CD48 in AML patients expressing PML-RARA and AML1-ETO. We initially used data from Amazonia (http://amazonia.transcriptome.eu/), a publicly available human transcriptome resource obtained from patients.55 According to this database (probe num. 204118) the relative expression of CD48 is significantly lower in patients expressing the AML oncogenes as compared with normal bone marrow samples (median in PML-RARA = 253.5 and in AML1-ETO = 150.95, compared with median in patients with normal bone marrow = 517.1, P < .001, Student t test, Figure 7A). Similar results were obtained with an additional probe (probe num. 237759, data not shown).

Reduced CD48 expression in AML patients. (A) The relative expression of CD48 in samples of normal bone marrow (BM) was compared with samples of AML patients that express PML-RARA or AML1-ETO. Data obtained from Amazonia! (http://amazonia.transcriptome.eu/). Black horizontal line represents the median value. (B) Expression of CD48 in the BM of patients that were treated in Hadassah Medical Center. Relative copy number of CD48 was determined by qRT-PCR. The expression of 1 of the normal bone marrow samples was arbitrarily defined as 1. The results were normalized to 3 housekeeping genes (HPRT, UBC, and SDHA). The black horizontal lines represent the median value. ***P < .001, Student t test.

Reduced CD48 expression in AML patients. (A) The relative expression of CD48 in samples of normal bone marrow (BM) was compared with samples of AML patients that express PML-RARA or AML1-ETO. Data obtained from Amazonia! (http://amazonia.transcriptome.eu/). Black horizontal line represents the median value. (B) Expression of CD48 in the BM of patients that were treated in Hadassah Medical Center. Relative copy number of CD48 was determined by qRT-PCR. The expression of 1 of the normal bone marrow samples was arbitrarily defined as 1. The results were normalized to 3 housekeeping genes (HPRT, UBC, and SDHA). The black horizontal lines represent the median value. ***P < .001, Student t test.

To further verify these findings we also tested the expression of CD48 in the bone marrow of patients that were treated in the Department of Hematology in Hadassah Medical Center. We collected samples of AML patients who express PML-RARA or AML1-ETO as well as samples of normal bone marrow. The relative expression of CD48 in these samples was determined by qRT-PCR using specific primers for CD48. In accordance with the Amazonia database, this analysis demonstrated that AML patients who express these AML oncogenes have low expression of CD48 as compared with normal bone marrow patient samples (median in PML-RARA = 0.82, in AML1-ETO = 0.65, compared with median in patients with normal bone marrow = 1.56, P < .001, Student t test, Figure 7B).

We also compared the expression of CD48 between patients expressing the fusion proteins and AML patients with normal cytogenetics (NC-AML). In this case we noted differences only in the Amazonia database (median in PML-RARA = 253.5 and in AML1-ETO = 150.95, compared with median in patients with NC-AML = 459.9, P < .001, Student t test, n = 258 of NC-AML). Similar results were obtained with probe num. 237759 (data not shown). However, in our patient samples, the difference was not significant (median and mean in NC-AML patients 0.47 and 0.77 correspondingly, n = 21 of NC-AML).

Discussion

Two common chromosomal translocations in AML are t(15:17) and t(8:21) which generate the fusion proteins PML-RARA and AML1-ETO, respectively. Here we studied these oncogenic fusion proteins of AML and their effect on NK cell activity both by overexpressing them in the U937 cell line as well as by investigating cell lines which endogenously express these fusion proteins. We demonstrate that the AML fusion proteins specifically downregulate the expression of the NK cell ligand CD48, which results in reduced killing by NK cells. Our observations are supported by the results of a recently published microarray,50 demonstrating that the expression of CD48 increased significantly after knockdown of AML1-ETO in the Kasumi-1 cell line. In addition, we demonstrated that AML1-ETO directly binds to CD48. We also show that our findings are relevant to human patients and that treatment with class I HDACi restores the expression of CD48. Interestingly, the two types of AML bearing these translocations have a relatively favorable prognosis.56,57 However, the better prognosis of these types of AML might be related to other, non-immune mechanisms. Thus it is possible that treatments which increase the expression of CD48 could lead to an even better outcome for patients with these types of AML.

It is not possible to test the effect of these AML fusion proteins on CD48 expression in a mouse model since the mouse 2B4 is considered to be mainly an inhibitory receptor,28,58,59 as opposed to the activating human 2B4 receptor.25-27 In addition, the site in the human CD48 that we found to be directly targeted by AML1-ETO is not found in the mouse CD48. We therefore investigated the relevance of our findings by using data of AML patients expressing the oncogenic fusion proteins PML-RARA or AML1-ETO. We demonstrated both by the patient-based online Amazonia database, as well as by samples of patients hospitalized in our hospital, that expression of the AML fusion proteins correlates with low levels of CD48 expression. Although these data do not prove directly an immune evasion process by the fusion proteins in humans, they emphasize the relevance of our findings to human AML patients. We also compared the CD48 expression in these types of AML to cytogenetically normal AML (NC-AML). While a difference between these groups was found in the Amazonia database, no such difference was found in our patients. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the NC-AML group includes a heterogonous group of patients (as we noted in the dispersion of CD48 expression in our group of NC-AML patients). In addition, it is possible that in other types of AML that do not express the AML fusion proteins, CD48 is also downregulated by other mechanisms.

We showed that the downregulation of CD48 was more pronounced in the presence of AML1-ETO as compared with PML-RARA. This could be a result of different levels of expression of these fusion proteins or due to intrinsic differences between the two fusion proteins. The latter possibility is supported by the results of human patients, in which lower CD48 expression was observed in patients bearing the AML1-ETO fusion protein. The difference in the efficiency of CD48 downregulation by the two fusion proteins is also in line with the ChIP-seq data53,54 and with our ChIP experiments. Although direct binding to CD48 was observed in the case of AML-1-ETO (and our own results [Martins et al53 ]), PML-RARA has no such clear binding site,54 suggesting that it regulates CD48 indirectly.

Despite the fact that CD48 was more efficiently downregulated by AML1-ETO, the cytotoxic activity of NK cells was reduced to similar levels by both fusion proteins. This may be due to a killing threshold that is set by a certain level of CD48 expression as demonstrated by our experiments. Below such a threshold, reduction in the levels of CD48 has no further effect on the extent of killing by the NK cells. A similar threshold effect was seen in the case of the NKG2D ligand ULBP3.60 The downregulation of CD48 may have additional significance in relation to T-lymphocytes,61 but this aspect remains to be explored in future studies.

We showed that the fusion protein-mediated CD48 downregulation operates via HDAC. Treatment with HDACi upregulated CD48 expression in cells expressing the fusion proteins (both in the transduced cells and in cells that endogenously express the fusion proteins). Furthermore, we show that mutating the HDAC complex binding site in both fusion proteins abolished the downregulation of CD48. Not all HDACi increased the expression of CD48. The specific class I HDACi mocetionostat and entinostat increased CD48 expression, but TSA, which is considered a pan-inhibitor of HDAC activity43 and sodium valproate, did not. In agreement with these results, a recent paper demonstrated that mocetinostat and entinostat, but not TSA or sodium valproate, increased the expression of LAT2, which is a target of AML1-ETO.32 Our results raise the possibility that treatment with certain HDACi may be effective in AML patients bearing these fusion proteins. Such treatment can be combined with ATRA in case of acute promyelocytic leukemia (the AML type that is associated with PML-RARA), especially because we found that ATRA alone does not reverse the downregulation of CD48. Finally, it would be interesting to have a future study on whether the downregulation of CD48 by these AML fusion proteins is common to other oncogenic fusion proteins or to other types of AML.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yoav Smith and Tamar Kahan from the Genomic Data Analysis Unit of the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School (Jerusalem, Israel) for their help in the bioinformatics analyses, and Svetelana Krichevsky from the Department of Hematology, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center (Jerusalem, Israel) for her help in qRT-PCR.

This study was supported by grants from the Israeli Science Foundation, the Israel Cancer Research Fund professorship grant, the Israeli Centers for Research Excellence, the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development grant, the Lewis Family Trust, the European Research Council advanced grant (O.M.), and by the Hadassah Medical Center physician scientist program and the Hadassah-Hebrew University joint research fund (S.E.). O.M is a crown professor of Molecular Immunology.

Authorship

Contribution: S.E. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the paper; R.Y., L.G., P.T., and N.S.K. assisted in performing experiments; D.B.Y. handled the human patient samples; and O.M. supervised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ofer Mandelboim, Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, 91120 Israel; e-mail: oferm@ekmd.huji.ac.il.