Key Points

We identified novel recurrently mutated genes, including WHSC1, RB1, POT1, and SMARCA4, through exome sequencing of 56 cases of MCL.

Genetic mutations defining MCL and Burkitt lymphoma were associated with the epigenetically defined chromatin state of their respective B cells of origin.

Abstract

In this study, we define the genetic landscape of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) through exome sequencing of 56 cases of MCL. We identified recurrent mutations in ATM, CCND1, MLL2, and TP53. We further identified a number of novel genes recurrently mutated in patients with MCL including RB1, WHSC1, POT1, and SMARCA4. We noted that MCLs have a distinct mutational profile compared with lymphomas from other B-cell stages. The ENCODE project has defined the chromatin structure of many cell types. However, a similar characterization of primary human mature B cells has been lacking. We defined, for the first time, the chromatin structure of primary human naïve, germinal center, and memory B cells through chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing for H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, H3K27me3, and PolII. We found that somatic mutations that occur more frequently in either MCLs or Burkitt lymphomas were associated with open chromatin in their respective B cells of origin, naïve B cells, and germinal center B cells. Our work thus elucidates the landscape of gene-coding mutations in MCL and the critical interplay between epigenetic alterations associated with B-cell differentiation and the acquisition of somatic mutations in cancer.

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by a generally high relapse rate and mortality. Although translocation of CCND1 is a defining feature of the disease, the role of collaborating somatic mutations that contribute to MCL remains to be further defined.1-3

Cancers have traditionally been classified based on their anatomic tissue of origin. Hematopoietic malignancies (leukemias and lymphomas) in particular have been extensively subclassified beyond tissue of origin, based upon the specific point in the B-cell differentiation stage from which they are thought to arise. Thus, the study of these tumors enables the direct comparison between the normal stages of cell differentiation and tumors that are thought to arise from them.

As we better understand the genetic abnormalities underlying tumors, it is unclear whether the traditional methods of classifying tumors based on their tissue of origin remain useful. For instance, it has been proposed that tumors could be reclassified based on their particular mutational profiles rather than their cell of origin.4 Although some genes appear to be mutated frequently in a large number of cancers (eg, TP53), a number of oncogenes have been found to be relatively specific to certain cancers. The lineage specificity of mutations has not been fully defined.

A number of genes related to B-cell differentiation are recurrently mutated in lymphomas (eg, BCL65 and EZH26 ). Expression of mutant EZH2 hampers germinal center (GC) differentiation and drives aberrant proliferation.7 However, the relationship between the differentiation stage and the development of specific mutations in cancers remains to be defined. Although early efforts have attempted to characterize the association between chromatin structure and genetic alterations, they have been limited to aggregate alterations at the megabase scale8 or rearrangement breakpoints9 or known risk variants.10 Work comprehensively defining the chromatin state of >1 normal cell type and direct association of gene mutations in tumors that arise from those normal cells has been lacking.

The ENCODE project11 has elucidated the chromatin structure of a number of cell types, but a similar definition of primary human mature B cells has been lacking. A particular advantage of studying mature B cells is that their relationship to leukemias and lymphomas is far better defined compared with other cell types (eg, those corresponding to solid tumors). In this study, we sought to better understand the role epigenetic alterations that determine chromatin structure play in the gene expression and mutational profiles of B-cell tumors.

We performed exome sequencing in 56 cases of MCL to broadly identify the mutational landscape of the disease. We noted that the genetic profiles of MCLs were distinct from other aggressive lymphomas. We then defined the chromatin structure of the normal-counterpart B cells (naïve and GC B cells, respectively) for MCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) by profiling their epigenetic markers using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for the markers H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, H3K27me3, and PolII. We found that the somatic mutational profiles of MCL and BLs overlapped strongly with areas of open chromatin in their normal-counterpart B cells, identifying the epigenetically determined chromatin structure in normal B cells as a potential determinant in the acquisition of somatic mutations.

Thus, our data define the broad genomic landscape of mutations in MCL and point to an interplay between epigenetic states in normal cells and the development of genetic alterations that lead to cancer.

Methods

MCL sample acquisition and processing

MCL tumors (n = 56) and normal tissue (n = 28) were obtained from the institutions that constitute the Hematologic Malignancies Research Consortium.12 Genomic DNA was extracted as described previously.12 Patient tumor and normal samples were collected according to institutional review board guidelines. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exome capture and library preparation

Genomic DNA was sheared to 250 bp using the Covaris S2 platform. Exome capture libraries were prepared as described previously.13

B-cell isolation

Tonsils were obtained according to institutional review board guidelines from patients undergoing routine tonsillectomy at a North Carolina hospital. Mononuclear tonsillar B cells were prepared and stained as described previously.14 Stained cells were fluorescence-activated cell sorted into 10 million each of naive B cells (CD19+IgD+CD27−CD38+), GC B cells (CD19+IgD−CD38++), and memory B cells (CD19+IgD−CD27+CD38dim) for each chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) antibody.

ChIP and sequencing library preparation

Flow-sorted B cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde, pelleted, lysed, and sonicated to a median size of ∼200 bp. After sonication, the nuclear extract was washed and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies coupled to magnetic beads (Invitrogen, 112.03D): anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore, 07-473), anti-H3K4me1 (Abcam, ab-8895), anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore, 07-449), anti-H3Ac (Millipore, 06-599), anti-PolII (Santa Cruz, sc-899x), and anti-H3K36me3 (Abcam, ab-9050). Isotype-matched immunoglobulin G control antibodies were used in parallel as a negative control. The beads were washed, and the immunoprecipitated complex was eluted and reverse crosslinked at 65°C overnight. The samples were subsequently digested and purified. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina Genomic DNA Sample Prep kit (FC-102-1001) according to the provider’s protocol.

Exome data processing and analysis

Exome sequence alignment, variant calling, and annotation.

Reads in fastq format15 were preprocessed with GATK16 to remove Illumina adapter sequences and Phred-scaled base qualities of 10 and below as described previously.17 After GATK processing, reads were mapped to hg18 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner18 followed by Novoalign V2.06.09 (http://www.novocraft.com). Remaining unmapped reads were clipped to 35 bp to remove adapter matches in the 3′ end of the read and realigned with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.

All alignments were output as BAM files19 and merged using Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net). The data will be available on dbGaP. Polymerase chain reaction/optical duplicates were marked by Picard. Base quality recalibration was performed using GATK. To improve accuracy and quality of the calls, localized indel realignments were performed using GATK.16 Regions that should be realigned are determined by the GATK Realigner Target Creator. Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indel variants were called using SAMtools.20 SAMtools mpileup was run on all cases and output to a single VCF file. Each variant was required to have an instance of genotype quality >30 and read depth >5. Individual SNVs and indels were annotated with gene names and predicted function using Annovar (http://wannovar.usc.edu/).21

Identification of somatically acquired mutations using muTect.

muTect22 was used to identify somatic mutations in the 28 MCL tumor-normal pairs. BAM files were generated as described above. muTect version 1.1.1 was executed on each tumor-normal pair.

Control exomes.

In addition to NHLBI 6500 exomes (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), 1000 Genome Project,23 and dbSNP13524 frequencies, we also filtered our MCL variants against 189 noncancer exomes generated in-house and 256 publicly available exomes that we reprocessed.25,26 This allowed us to reduce the number of variants observed that are simply part of normal human variation.

Coverage.

Sanger sequence validation.

DNA regions of interest were amplified using primers designed to target exonic regions containing the variant, as described previously.28 The amplified fragments were verified by agarose gel, and reactions were purified with ExoSAP-IT using the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix, 78250).

Significantly differentially mutated genes.

Differentially mutated genes were selected for further analysis by Fisher’s exact test between the number of mutated and unmutated cases in BL and MCL (P < .05).

Gene pathway analysis.

Using GATHER Gene Ontology annotation (http://gather.genome.duke.edu/) and GSEA MSigDB (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp), enrichment of this set of 37 MCL mutated genes was measured in known gene lists. Enrichment was considered to be significant at a false discovery rate q < 0.05.

ChIP-seq data processing and analysis

Alignment and peak calling

The B cell ChIP-seq and mock samples were aligned to the reference human genome (hg19) using Bowtie.29 Significantly (P < .0001, false discovery rate < 5%) enriched peak regions were detected with MACS software30 using the following parameters: −nomodel, –shiftsize = 100, –bw = 250, –mfold = 10, 30, -w -S, -g hs, –P value = .0001. The data will be available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Characterizing ChIP-seq reads in gene regions.

For each pair of ChIP marker and B-cell sample (naïve and GC), a score was calculated for each gene in a similar fashion to RNA-sequencing reads per kilobase per million. Specifically, for each gene region (5 kb padded on either side), the number of aligned reads to fall in that gene region were counted using coverageBed.27 This number is divided by the length of the gene region in base pairs, and again by the total number of aligned reads in that particular sample, to adjust for coverage differences. The scores were multiplied by 1 billion to get to a reasonable number range and log2 transformed. Transcription start and stop sites for each gene were extracted from RefSeq. Gene-region BED files, padded by 5 kb on either end of the transcription start and stop sites, were generated in hg19 using BEDTools. Differences between naïve and GC cells were calculated by subtracting the GC score from the naïve score for corresponding genes and markers.

Open chromatin calculation.

The open chromatin score for each gene is defined as the sum of H3K4me1, H3Ac, and H3K36me3 individual gene scores. Differences between naïve and GC cells are calculated by subtracting one cell type chromatin score from the other.

Microarray data analysis

Microarray data from public sources (BL, MCL, B cell).

All gene expression microarray data were generated on the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 platform. BL gene expression microarray CEL files were published previously.31 MCL gene expression microarray CEL files were downloaded from the GEO (accession number GSE21452).18 GC and naïve B-cell gene expression microarray data were published previously14 and are available under GEO accession number GSE12366.

Processing microarray data and selecting significant genes.

BL, MCL, and B-cell expression CEL files were normalized together using robust multiarray average.32 Differentially expressed genes between naïve and GC B cells were selected using a Student t test P value < .05, absolute fold change >1, and mean expression >5.5.

Results

Exome sequencing reveals recurrent genetic alterations in MCL

We performed exome sequencing on 56 MCL tumors, 28 with paired normal tissue (ie, total 84 exomes). DNA was extracted from these tissues, and paired-end sequencing libraries were constructed, followed by exome-enrichment using a solution-based capture approach available commercially through Agilent. On average, we achieved 102-fold coverage of the targeted exonic regions. Greater than 90% of the targeted exons were covered at an average depth exceeding 10-fold.

Sequencing reads were mapped to the reference human genome, and high-quality mismatches were classified as synonymous and nonsynonymous variants. Nonsynonymous variants were further subclassified as missense, nonsense, and small insertions/deletions (indels). Missense variants comprised the highest proportion of alterations (48.4%), whereas synonymous and nonsense variants and indels comprised 46.8%, 0.7%, and 4%, respectively.

We verified the accuracy of identifying genetic variants through deep sequencing by performing Sanger sequencing in the same cases for 53 distinct variants. As in our previously described work with hundreds of variants,13,17 we found >90% agreement between the 2 methods. These results confirmed the accuracy of our methods for high-throughput sequencing and identifying genetic variants.

Defining the landscape of gene mutations in MCL

We initially examined the exomes of the MCL cases with paired germline DNA. We identified somatic mutations affecting 537 genes in at least 1 tumor/germline pair among these cases. Transitions comprised the majority of the somatic variants (P < 10−3, χ2 test). On average, we observed 32 somatic alterations per sample (range, 1-61), a rate similar to that which we observed in BL cases17 and approximately half the rate we observed in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).13 Upon inclusion of an additional 28 validation samples in our analysis, we identified 1189 rare variants corresponding to these 537 somatically mutated genes. These variants were not present in publicly available data from normal controls including dbSNP135,24 the 1000 Genomes Project,23 and available exome sequencing data from healthy individuals without lymphoma.25,26

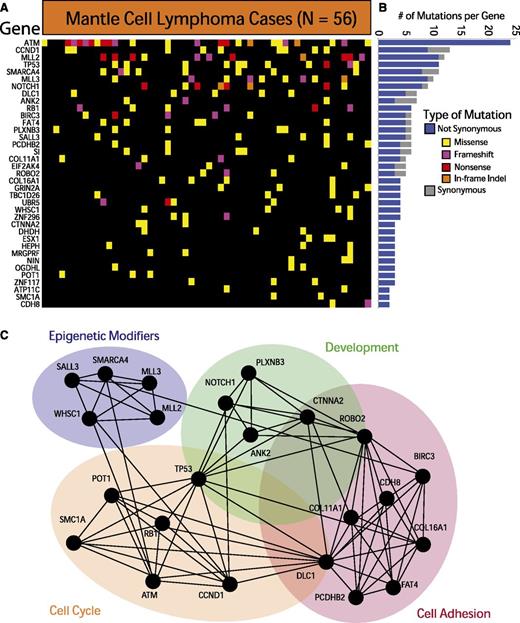

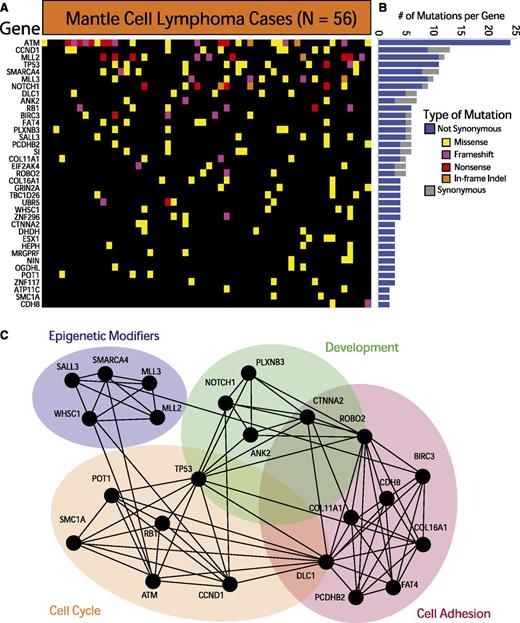

We further required each of the identified genes to have 3 somatically acquired and/or nonsynonymous rare events predicted to be functionally significant. These methods, detailed in the supplemental Methods available at the Blood Web site, allowed us to identify 37 recurrently mutated genes in MCL. These genes are depicted in Figure 1A and listed in supplemental Table 2. The individual variants are listed in supplemental Table 3. The relative frequency of synonymous and nonsynonymous variants for each gene is shown in Figure 1B. A total of 12 of the 37 genes have been previously implicated in cancer.33

Exome sequencing in MCL reveals recurrently mutated genes. (A) The heatmap indicates the pattern of nonsynonymous mutations of the 37 most significantly implicated genes in 56 cases of MCL. Each column represents a patient, and each row represents a gene. Mutations are color-coded with yellow for a missense mutation, purple for a frameshift mutation, red for a nonsense mutation, and orange for an in-frame insertion or deletion. (B) The bar graph indicates the frequency of variants found by gene across all samples, subdivided by not-synonymous (blue) and synonymous (gray) mutations. (C) The network indicates functional groupings of the genes mutated in MCL. Nodes represent significantly mutated genes that are also a part of a significant functional group. Edges connect nodes that belong to the same functional gene set. Colored ovals identify the gene sets to which these nodes belong.

Exome sequencing in MCL reveals recurrently mutated genes. (A) The heatmap indicates the pattern of nonsynonymous mutations of the 37 most significantly implicated genes in 56 cases of MCL. Each column represents a patient, and each row represents a gene. Mutations are color-coded with yellow for a missense mutation, purple for a frameshift mutation, red for a nonsense mutation, and orange for an in-frame insertion or deletion. (B) The bar graph indicates the frequency of variants found by gene across all samples, subdivided by not-synonymous (blue) and synonymous (gray) mutations. (C) The network indicates functional groupings of the genes mutated in MCL. Nodes represent significantly mutated genes that are also a part of a significant functional group. Edges connect nodes that belong to the same functional gene set. Colored ovals identify the gene sets to which these nodes belong.

The most frequently mutated genes in MCL were ATM (41.9%), CCND1 (14%), MLL2 (19.6%), and TP53 (18.6%). Other frequently mutated genes included known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes such as RB1, SMARCA4, APC, NOTCH1, and UBR5. Our data also implicated a number of genes not previously associated with MCL, including POT1, FAT4, and ROBO2. Silencing mutations (frameshift and nonsense mutations) comprised a sizeable fraction of the genetic events in ATM, MLL2, MLL3, RB1, and ROBO2, suggesting that those alterations result in a loss of function in MCL.

Pathway and gene-set analysis of the significantly mutated genes reveals a crucial role for many of these genes in cell-cycle regulation (SMC1A, POT1, and RB1), cell adhesion (FAT4, DLC1, and CDH8), development (ROBO2, ANK2, and CTNNA2), and chromatin modification (SMARCA4, MLL2, MLL3, and WHSC1). Figure 1C illustrates the links between mutated genes that belong to the same functional gene sets.

Genetic differences between MCL and other lymphomas

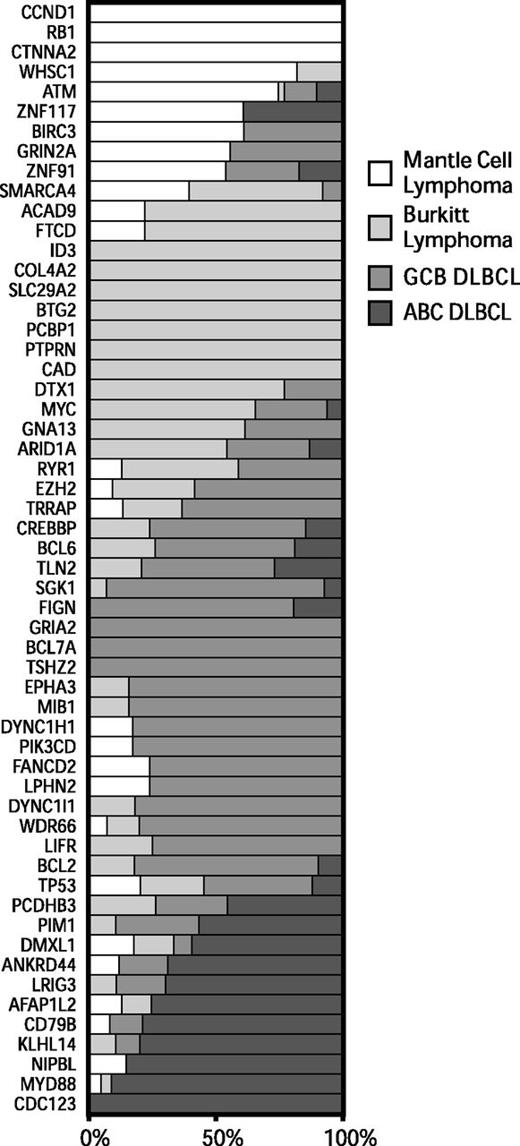

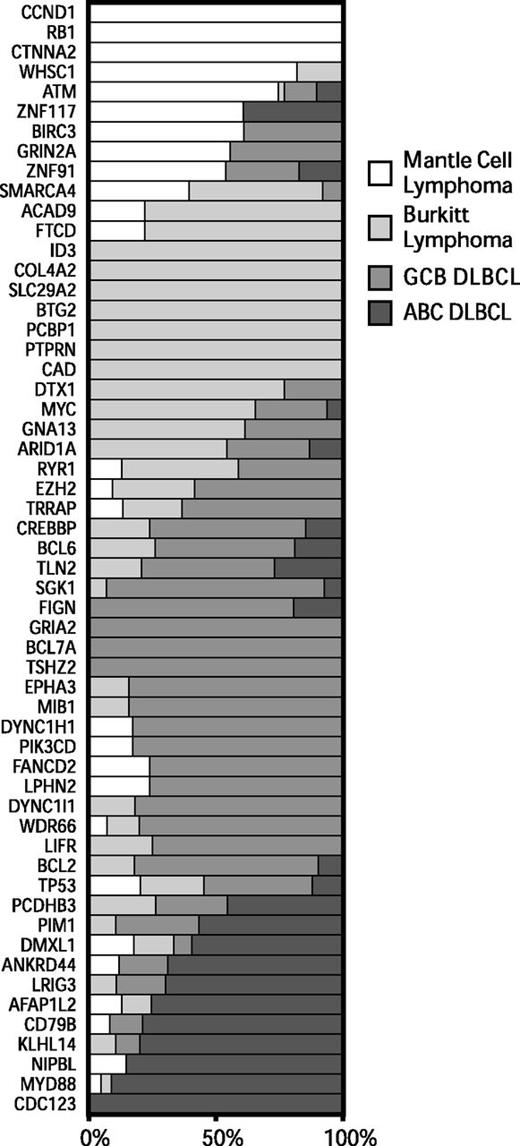

To better understand the genetic differences between common non-Hodgkin lymphomas, we analyzed exome sequencing data that we13,17 and others5,34-37 have generated from BL and DLBCL. We identified all genes that were mutated at a frequency of 10% or higher in at least 1 tumor type and differentially mutated among at least 1 of the lymphoma types (P < .05, Fisher’s exact test). We plotted the relative frequencies of these genes for MCL, BL, and the molecular subgroups of DLBCL in Figure 2.

Patterns of exonic mutations across lymphomas show similarly and differentially mutated genes. The bar graph depicts the proportion of mutated cases that belong to each lymphoma type for MCL, BL, GCB DLBCL, and ABC DLBCL. ABC, activated B-cell like; GCB, germinal center B-cell like.

Patterns of exonic mutations across lymphomas show similarly and differentially mutated genes. The bar graph depicts the proportion of mutated cases that belong to each lymphoma type for MCL, BL, GCB DLBCL, and ABC DLBCL. ABC, activated B-cell like; GCB, germinal center B-cell like.

We found a number of genes that were predominantly mutated in each disease. Mutations in ATM, CCND1, and RB1 occurred mostly in MCL. Mutations in ID3 and MYC occurred predominantly in BL. Mutations in PIM1, BCL2, and CREBBP occurred mostly in DLBCLs. A number of genes had overlapping patterns of mutations between 2 or more of the diseases, including TP53, GNA13, ARID1A, and SMARCA4.

We further examined the association between individual genes that were recurrently mutated in these diseases (supplemental Figure 2). We found that ATM and RB1 mutations tended to co-occur in the same cases, reflecting their involvement in the DNA damage response and its importance in MCL.

Epigenetic profiling of normal B cells and its relationship to gene expression

Gene expression and replication must be preceded by conformational changes in the chromatin to an open state.38 We sought to define the relationship between the epigenetically determined chromatin state of primary mature B cells and the lymphomas that are thought to arise from them.

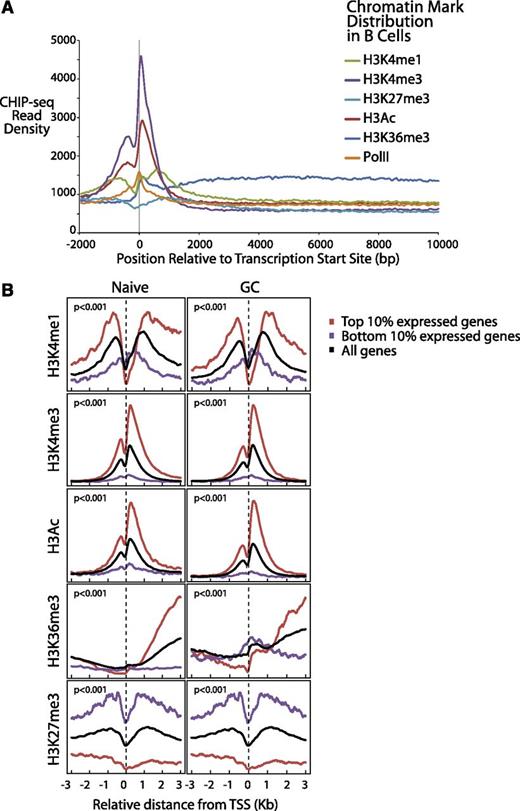

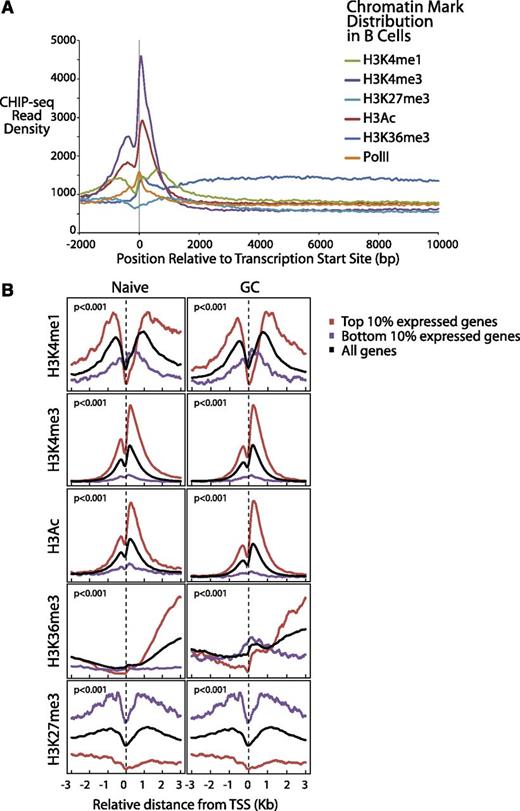

We performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting of normal naïve B cells, GC B cells, and memory B cells from otherwise-normal individuals undergoing tonsillectomy (>95% purity verified by flow cytometry in each case).14 We profiled the chromatin structure and epigenetic state of the normal B cells through ChIP-seq on 6 different markers: H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3Ac, H3K27me3, H4K36me3, and PolII. These markers collectively identify a comprehensive epigenetic portrait of these primary human cells. A few of these markers have been published previously in B cells, and the identified regions overlap strongly with our data.7

We plotted (Figure 3A) the aggregate density for each of the 6 markers associated with gene expression over a range from 2 kb upstream to 10 kb downstream of all Consensus CDS–annotated transcription start sites (TSS). Consistent with work in other cell types,38,39 we found that H3K4me1 and H3Ac exhibited strong peaks before and after the TSS, PolII, and H3K4me3 peaked directly at the TSS and H3K36me3 exhibited elevated levels through the gene body (Figure 3A), reflecting transcriptionally active genes. H3K4me3 levels declined rapidly over the gene body, consistent with the notion that it marks promoter sites. The repressive marker H3K27me3 also was elevated before and after the TSS, an indication of the transcriptionally inactive genes.

Differential gene expression of normal B cells correlates with B-cell chromatin profiles and gene expression of corresponding lymphomas. (A) Epigenetic profiles of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27 me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, and PolII are shown in 50-bp read resolution from 2 kb upstream to 10 kb downstream of all annotated TSSs. (B) Epigenetic profiles of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, and H3K27me3 around the TSSs are shown for the top 10% most expressed, bottom 10% expressed, and all genes for naïve and GC B cells.

Differential gene expression of normal B cells correlates with B-cell chromatin profiles and gene expression of corresponding lymphomas. (A) Epigenetic profiles of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27 me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, and PolII are shown in 50-bp read resolution from 2 kb upstream to 10 kb downstream of all annotated TSSs. (B) Epigenetic profiles of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3Ac, H3K36me3, and H3K27me3 around the TSSs are shown for the top 10% most expressed, bottom 10% expressed, and all genes for naïve and GC B cells.

We further plotted the chromatin epigenetic marker profiles around the TSSs for both highly and lowly expressed genes for each cell type.12 We observed similar patterns in both cell types (Figure 3B). The genes that were expressed the most highly in these B cells were highly associated (P < 10−6, Pearson correlation test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) with the epigenetic alterations that identify open chromatin (H3K4Me1, H3K4Me3, H3Ac, and H3K36Me3). Conversely, the epigenetic alteration associated with closed chromatin (H3K27Me3) was found to be highly associated with repressed gene expression. The markers H3K4Me1, H3Ac, and H3K36Me3 were most strongly associated with the gene body, whereas H3K4Me3 was most strongly associated with promoter regions, as has been described previously.38

Role of B-cell differentiation stage in MCL

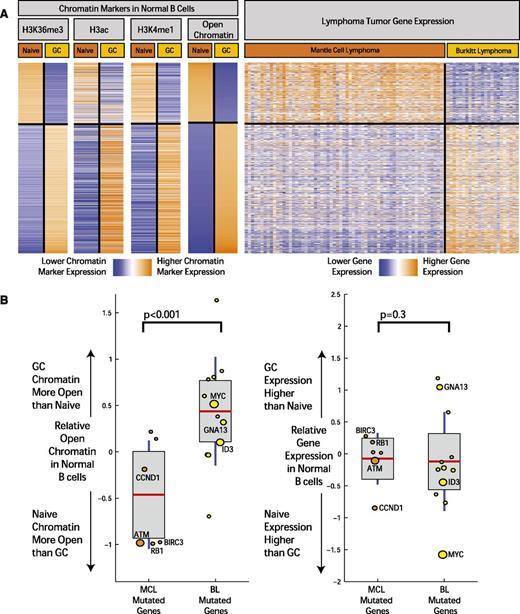

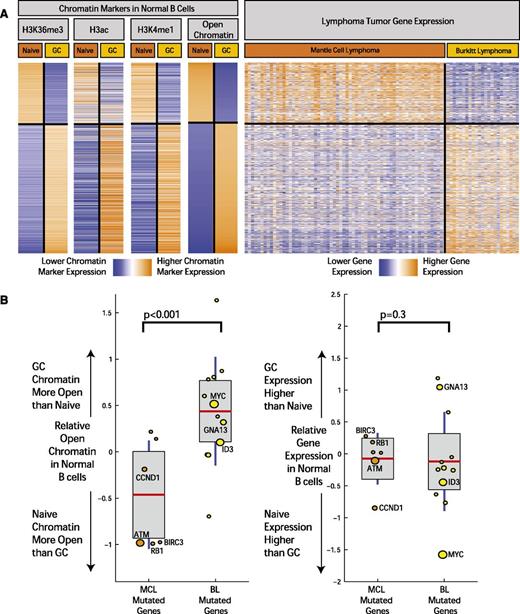

Although B-cell differentiation state is the basis for classifying lymphomas, the extent to which it is related to the molecular profiles of MCL and other lymphomas has not been fully defined. In order to investigate this further, we examined the relationship between differentially activated chromatin marks between cell types and gene expression in the tumors of corresponding cell of origin (Figure 4A). Based on the observed patterns of distribution of chromatin marks and the body of the gene, we defined open chromatin in all gene regions as a combination of marks corresponding to H3K36me3, H3ac, and H3K4me1. Differential chromatin levels for each gene were calculated by computing the difference of total number of aligned ChIP-seq reads from naïve and GC B cells that fell within the gene region, normalized by the length of the gene and the sequencing library size, similar to methods described previously (supplemental Table 4).38

Open chromatin differences between B-cell differentiation stages associate with expression differences and mutation frequency in corresponding lymphomas. (A) The heatmap depicts the chromatin signal at gene level for H3K36me3, H3ac, and H3K4me1 open chromatin markers in genes with the most significant open chromatin differences between normal and GC B cells. On the rightmost heatmap, gene expression in MCL samples (64 cases) and BL (23 cases) is indicated for the same genes. Orange indicates higher chromatin signal or higher gene expression, and blue indicates lower. (B) The boxplots on the left illustrate difference in open chromatin score for genes differentially mutated between BL and MCL. On the horizontal axis, “MCL Mutated Genes” is defined as genes with a significantly higher mutation rate in MCL compared with BL (and the reverse for “BL Mutated Genes”). The boxplots on the right indicate expression fold change between normal GC and naïve B cells for the same 2 sets of genes. The size of the individual data points is scaled to the number of mutated cases in the corresponding disease.

Open chromatin differences between B-cell differentiation stages associate with expression differences and mutation frequency in corresponding lymphomas. (A) The heatmap depicts the chromatin signal at gene level for H3K36me3, H3ac, and H3K4me1 open chromatin markers in genes with the most significant open chromatin differences between normal and GC B cells. On the rightmost heatmap, gene expression in MCL samples (64 cases) and BL (23 cases) is indicated for the same genes. Orange indicates higher chromatin signal or higher gene expression, and blue indicates lower. (B) The boxplots on the left illustrate difference in open chromatin score for genes differentially mutated between BL and MCL. On the horizontal axis, “MCL Mutated Genes” is defined as genes with a significantly higher mutation rate in MCL compared with BL (and the reverse for “BL Mutated Genes”). The boxplots on the right indicate expression fold change between normal GC and naïve B cells for the same 2 sets of genes. The size of the individual data points is scaled to the number of mutated cases in the corresponding disease.

We examined the gene expression profiles of MCLs18 and BLs31 performed on the same microarray platform. We observed a striking overlap (Figure 4A) between the epigenetic profiles defining open chromatin in naïve and GC cells and the gene expression profiles that distinguish MCL and BL, an overlap that was highly statistically significant (P < 10−6, χ2 test) and likely reflected the similarity of these tumors to their supposed cells of origin.

Thus, we concluded that the epigenetically defined regions of open chromatin of their cells of origin are highly related to gene expression profiles of MCL and BL.

Epigenetic profiling of normal B cells and its relationship to mutations in lymphoma

We next examined the association between the mutational patterns observed in MCL and BL and these chromatin marks in their cells of origin, naïve B cells, and GC B cells. We defined an open chromatin score for each gene using a sum of the markers for open chromatin on the gene body (H3K36Me3, H3Ac, and H3K4Me1; Figure 4A and supplemental Appendix 4).

Using these epigenetic markers, differences in open chromatin between naïve B cells and GC B cells were computed for genes that were differentially mutated in MCL and BL. We plotted the relative state of open chromatin in naïve and GC B cells (Figure 4B; individual markers shown in supplemental Appendix 4) in these genes. We found that difference in gene mutation frequency between MCL and BL is highly associated with differences in open chromatin in their corresponding cells of origin (P < .001, χ2 test). Differences in mutation frequency were not associated with expression differences of these genes in the normal B cells (Figure 4B). In addition, those genes mutated in both BL and MCL without significant differences in mutation rate did not show significant differences in open chromatin between the corresponding normal B-cell types.

Discussion

Our data identify the genetic heterogeneity underlying MCL and implicate a number of novel genes in the development of the disease. Our study overlapped significantly with recently published studies of 29 tumor exomes40 and 18 transcriptomes2,39 (eg, ATM, CCND1, TP53, WHSC1, MLL2, NOTCH1, and UBR5) and targeted sequencing studies (eg, BIRC341 and ATM and TP5342 ). Our work implicates other mutated genes in the MCL including RB1, POT1, ROBO2, SMARCA4, and MLL3. Similar to other lymphomas,13 our data indicate a striking heterogeneity underlying MCLs, with relatively few genes mutated in >10% of the cases. Although our data indicate a paucity of activating mutations in oncogenes that can be readily targeted therapeutically, a functional analysis of gene mutations implicates cell-cycle progression, cell adhesion, and signal transduction as broad oncogenic processes that could be targeted.

If the acquisition of somatic mutations in tumors was completely stochastic, then one might expect that virtually every oncogene and tumor-suppressor gene to be involved in most cancers. However, most cancers show a degree of specificity in their mutational spectrum. Our work identifies B-cell stage as a critical determinant of acquired somatic alterations in lymphomas. “Lineage addiction” has been previously noted in the context of individual genes.43 Both BCL644 and EZH27 have already been defined as important regulators of B-cell differentiation and oncogenes in GC B-cell–derived tumors.6,45 Our study is among the first to define the extent to which B-cell stage is associated with mutations in lymphomas.

The state of differentiation of each cell type ultimately resides in the chromatin structure of the cells. The epigenetic modifications of histones enable the coiling and uncoiling of DNA that is a prerequisite for DNA repair, replication, and transcription. The ENCODE project11 has defined the chromatin structure of a number of cell types determining gene regulatory regions including promoters, enhancers, and insulators. To our knowledge, our data provide the first comprehensive description of these regions in human naïve, GC (dark zone), and memory B cells.

The normal cells of origin of hematopoietic malignancies are better defined than those of most other tumor types. Although our recognition of cells of origin is necessarily limited by our evolving knowledge of states of cellular differentiation that exist within every lineage, the mature B-cell types (GC dark zone cells and naïve cells) nevertheless capture the broad phenotypes of BL46 and MCL, respectively. MCLs arise from a subset of CD5-positive naïve cells, whereas a small proportion of mantle cells appear to be of post-GC origin. Nevertheless, the vast majority of MCLs largely maintain the phenotype of naïve B cells. This is highlighted by the strong overlap between the gene-expression profiles of naïve B cells and MCLs.

Chromatin structure has been shown to be a potential determinant of local mutation rates in different cancers.8,10 One recent study examined, at megabase scale, the relationship between relative mutational rates across the genome and corresponding chromatin structure.8 It found that genomic regions of higher SNV density associate with more closed chromatin.

Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to elucidate the relationship between differential gene-level mutation rates between 2 cancer types (MCL and BL) and the difference between chromatin states of their corresponding normal cells of origin (naïve and GC B cells). Our data indicate that at the gene level, the epigenetically defined differences in chromatin structure between naïve and GC B cells is independently associated with both expression profiles and mutational profiles of B-cell lymphomas derived from those cell types.

Mutation of chromatin-modifying genes has been found to be a recurrent feature of many cancers. In lymphomas, EZH2 mutations have been shown to modify H3K27me3, a process that might influence lymphoid transformation in GC-derived B cells. The role of transcription-associated mutagenesis has been described in prokaryotes47 and yeast.48 Although it is possible that similar mechanisms underlie cancers, the association between chromatin structure and mutation rates is not explained by transcription alone. There was no relationship between differential gene expression and mutation, suggesting that other unknown mechanisms underlie the association between mutations and chromatin structure.

Our study identifies the epigenetically defined chromatin structure of normal B cells as a common denominator of both expression profiles and mutational profiles of B-cell lymphomas. This work thus provides an important starting point for understanding the genetic diversity of MCLs and the interplay between genetic and epigenetic alterations in cancer.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants R21CA1561686 and R01CA136895 and by the Duke Cancer Institute and the Duke Center for AIDS Research. S.S.D. was supported by the American Cancer Society and the V Foundation. A.B.M. is supported by the Hertz Foundation and a National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship. The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous support of Charles and Daneen Stiefel.

Authorship

Contribution: S.S.D. designed research; Q.L., C.L., P.S., and J.Z. performed experiments; M.C., E.D.H., Y.F., C.H.D., K.L.R., D.S.H., J.I.G., and S.L. contributed samples or reagents; J.Z., D.J., A.B.M., Q.L., Z.S., E.L., D.D., and S.S.D. analyzed data; and S.S.D., J.Z., D.J., A.B.M., and Q.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sandeep S. Dave, 101 Science Dr, Duke University, Box 3382, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: sandeep.dave@duke.edu.

References

Author notes

J.Z., D.J., A.B.M., and Q.L. contributed equally to this study.