Key Points

FcγRIIA activation is key for platelet aggregation in response to bacteria, and depends on IgG and αIIbβ3 engagement.

PF4 binds to bacteria and reduces the lag time for platelet aggregation.

Abstract

Bacterial adhesion to platelets is mediated via a range of strain-specific bacterial surface proteins that bind to a variety of platelet receptors. It is unclear how these interactions lead to platelet activation. We demonstrate a critical role for the immune receptor FcγRIIA, αIIbβ3, and Src and Syk tyrosine kinases in platelet activation by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus sanguinis, Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. FcγRIIA activation is dependent on immunoglobulin G (IgG) and αIIbβ3 engagement. Moreover, feedback agonists adenosine 5′-diphosphate and thromboxane A2 are mandatory for platelet aggregation. Additionally, platelet factor 4 (PF4) binds to bacteria and reduces the lag time for aggregation, and gray platelet syndrome α-granule–deficient platelets do not aggregate to 4 of 5 bacterial strains. We propose that FcγRIIA-mediated activation is a common response mechanism used against a wide range of bacteria, and that release of secondary mediators and PF4 serve as a positive feedback mechanism for activation through an IgG-dependent pathway.

Introduction

Despite an increasingly recognized role for platelets in immunity,1-4 our knowledge of the molecular events that control platelet-bacteria interactions is rudimentary. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that acute and chronic infections play a role in the development and progression of cardiovascular and related diseases including infective endocarditis, atherothrombosis, and sepsis,5-9 and that this may involve direct activation of platelets by bacteria. Platelet activation can be responsible for the most severe sequelae of bacterial infection. For example, infective endocarditis is a focal infection of the heart valves characterized by inflammation that is associated with the build-up of platelets, fibrin, and bacteria on the valves of the heart.10 The biggest risk for patients is embolization of the clots to the brain, causing multiple small infarcts. Another life-threatening disease is sepsis, which can lead to sepsis-associated disseminated coagulopathy during which clotting factors are consumed by disseminated microvascular thrombosis. The bacterial species that are more frequently involved in these conditions include viridans group streptococci (Streptococcus sanguinis, Streptococcus gordonii, and Streptococcus oralis) and Staphylococcus aureus11,12 in infective endocarditis or Streptococcus pneumoniae in sepsis. Strains of these species have been shown to stimulate platelet aggregation and secretion directly.13-17

Bacteria can interact with platelets through a variety of mechanisms.4 Bacteria express proteins that recognize platelet receptors. For example, oral streptococci express a family of highly glycosylated serine-rich proteins that bind to platelet glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα): S sanguinis (expresses serine-rich protein A),16 S gordonii (hemagglutinin salivary antigen),17 and S oralis (whose GPIbα ligand has yet to be identified15 ). In addition, S gordonii expresses platelet adherence protein A18 and S aureus expresses iron-regulated surface determinant,19 both of which bind to platelet integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa). S pneumoniae binds to platelet Toll-like receptor 2 through an unidentified ligand. Bacteria also interact with plasma proteins that bind platelet receptors. For example, S aureus expresses cell wall proteins, clumping factors A and B (ClfA and ClfB) and fibronectin-binding protein A, which bind to fibrinogen and immunoglobulin G (IgG) leading to cross-linking of αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIA, respectively.4 Similarly, S aureus protein A can bridge von Willebrand factor to αIIbβ3.4,14 Additionally, secretion of prothrombin-activating molecules, staphylocoagulase and von Willebrand factor–binding protein, by S aureus promotes the formation of fibrin scaffolds that facilitate bacteria-platelet interactions.20 Furthermore, bacteria can secrete toxins that activate platelet receptors. For example, Porphyromonas gingivalis secretes the protease gingipain, which activates protease-activated receptor 121 and S aureus releases α-toxin that causes platelet secretion.4

Bacteria-induced platelet aggregation, as measured by Born aggregometry, is associated with a characteristic lag time that varies from seconds to several minutes and is then followed by full aggregation. In contrast, most platelet agonists cause rapid activation, which can give rise to partial aggregation when low concentrations of agonist are used. This suggests that bacteria have a unique positive feedback mechanism that gives rise to an “all-or-nothing” response.

FcγRIIA has been shown to play a role in mediating activation to several strains of bacteria.4,15 FcγRIIA is a low-affinity receptor for the Fc region of IgGs and is activated by immune complexes and other IgG-coated targets. FcγRIIA signals through Src and Syk tyrosine kinases via a dual YxxL sequence known as an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif that is present in its cytoplasmic tail.22 Pathologically, FcγRIIA plays a critical role in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), a potentially life-threatening disorder in which antibodies against platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin complexes induce platelet activation.23,24 It has recently been proposed that the natural targets for the HIT antibodies are PF4-coated bacteria, and that antibody recognition mediates bacterial clearance by polymorphonuclear leukocytes.25,26 FcγRIIA also functions as an adaptor protein for the major platelet integrin αIIbβ3 mediating signaling independent of extracellular engagement.27,28 Following activation by platelet agonists, αIIbβ3 shifts from its low affinity to a high-affinity state (“inside-out” signaling). Ligand-occupied αIIbβ3 in turn reinforces activation via “outside-in” signaling, which is mediated in part through FcγRIIA.27,28 Activated αIIbβ3 also mediates platelet aggregation by its ability to bind soluble fibrinogen, which bridges neighboring platelets.29

In the present study, we have investigated the hypothesis that bacterial activation of platelets is mediated through a common pathway that is dependent on FcγRIIA and that this pathway is reinforced during platelet activation possibly through secretion of PF4 and other secondary mediators.

Methods

Reagents

Fibrinogen was from Calbiochem (Merck Millipore). When indicated, fibrinogen was depleted of IgGs by incubation with protein A (rec-Protein A-Sepharose 4B Conjugate; Life Technologies). Pooled human IgGs (hIgGs) from healthy donors and unfractionated heparin (UFH) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Purified human PF4 was from ChromaTec. Anti-FcγRIIA monoclonal antibody (mAb) IV.3 was purified in the laboratory from a hybridoma. Anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 was from Life Technologies. Rabbit anti-human PLCγ2 polyclonal antibody (pAb) sc-407 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Goat anti-human BAF1330 (CD32/FcγRIIB Ab) was from R&D Systems. FcγRIIB is absent in human platelets and, therefore, this antibody can be used for the detection of FcγRIIA.30 Other reagents were from described sources or Sigma-Aldrich.31-34

Bacterial culture and preparation

Bacteria were gifts from Prof Mark Herzberg (University of Minnesota; S sanguinis 133-79), Prof Timothy Foster (Trinity College Dublin; S aureus Newman), Prof Howard Jenkinson (University of Bristol; S gordonii DL1, S pneumoniae IO1196), and Prof Ian Douglas (University of Sheffield; S oralis CR834).

All strains were cultured anaerobically at 37°C overnight and prepared as described.13,15 Washed bacteria were adjusted in phosphate-buffered saline to an optical density of 1.6 at a wavelength of 600 nm corresponding to the following concentrations: S sanguinis 133-79, 6 × 108 CFU/mL; S aureus Newman, 1 × 109 CFU/mL; S gordonii DL1, 3 × 109 CFU/mL; S oralis CR834, 4 × 109 CFU/mL; S pneumoniae IO1196, 7 × 108 CFU/mL. Bacteria were used at a 10-fold dilution in aggregation assays.

Human platelets

Blood was drawn in sodium citrate (for platelet-rich plasma [PRP]) or ACD-A (for washed platelets) from healthy volunteers who had not taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication in the previous 10 days. PRP15 and washed platelets35 were obtained as published. The study design was approved by the relevant ethics committees (Birmingham: ERN_11-0175; Dublin: REC679b). The gray platelet syndrome (GPS) patient was recruited to the United Kingdom Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets (UK GAPP) study (ISRCTN 77951167). Due to the slight increase in size of the platelets, PRP from the patient and a paired control was prepared at a reduced level of centrifugation (10 minutes at 100g). Approval was obtained from the institutional review board (number ERN_12-0799) for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Mouse platelets

Mice transgenic for human FcγRIIA were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and bred as heterozygotes. Controls were FcγRIIA-negative littermates. Blood was obtained as previously described.36 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid–Tyrode buffer36 was added to the blood at a ratio of 1:5 and PRP was obtained by centrifugation at 200g for 6 minutes. The recovered PRP was diluted in buffer (up to 50% dilution) to give a platelet concentration of ≥2 × 108 platelets/mL. All experiments were performed in accordance with UK laws with approval of local ethics committees and under Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 regulated licenses.

Aggregation and ATP secretion

Platelet aggregation was assessed by light transmission in a PAP-4 aggregometer for up to 30 minutes. Time-matched controls were run alongside. Stimulation by cross-linking of FcγRIIA was performed by preincubation of platelets for 3 minutes with mAb IV.3 (4 μg/mL) followed by anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 (30 μg/mL). Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release was assessed at the end of the recording using a luciferin-luciferase–based assay.13

PF4 secretion

Aggregation reactions were stopped at the end of the experiment by addition of prostacyclin (4 μM) and centrifuged at 1500g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Plasma supernatants were obtained for PF4 measurement by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Human CXCL4/PF4 ELISA; R&D Systems).

Protein phosphorylation

Aggregation reactions were stopped by addition of an equal volume of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and platelets were pelleted by centrifugation at 8500g for 30 seconds at 4°C. Platelets were lysed with ice-cold 1× lysis buffer plus inhibitors.31 Immunoprecipitations (IPs) and protein detection were conducted as previously described31 but without a preclearing step for FcγRIIA and Syk IPs (to preserve FcγRIIA). mAb IV.3 (mouse anti-human FcγRIIA), BR15 (rabbit anti-Syk pAb), and rabbit anti-human PLCγ2 pAb were used for IP. Samples were blotted for phosphotyrosine using mAb 4G10 and reprobed with biotinylated BAF1330 antibody for FcγRIIA and with the same IP antibodies for Syk and PLCγ2 followed by addition of anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase.

PF4 binding to bacteria

PF4 binding to bacteria was measured using biotinylated human PF4 (20 μg/mL) as previously described.25 Where indicated, bacteria-PF4 incubations were performed in the presence of 46% pooled plasma from healthy donors.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad (Prism). Data are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise stated, and comparisons between mean values were performed using the Student t test, or analysis of variance when multiple samples were compared. P < .05 (2-tailed) was considered significant.

Results

Bacteria stimulate platelet aggregation and secretion via FcγRIIA and αIIbβ3

The strains of the 5 bacterial species used in this study are known to induce “all-or-nothing” aggregation of platelets following a lag time that decreases with increasing concentrations of bacteria, as illustrated for 2 of them in supplemental Figure 1A-B (available on the Blood Web site). This is in contrast to the immediate onset and partial response induced by cross-linking of an intermediate concentration of mAb IV.3 to induce clustering of FcγRIIA,37 with full aggregation observed in response to a higher concentration (supplemental Figure 1C).

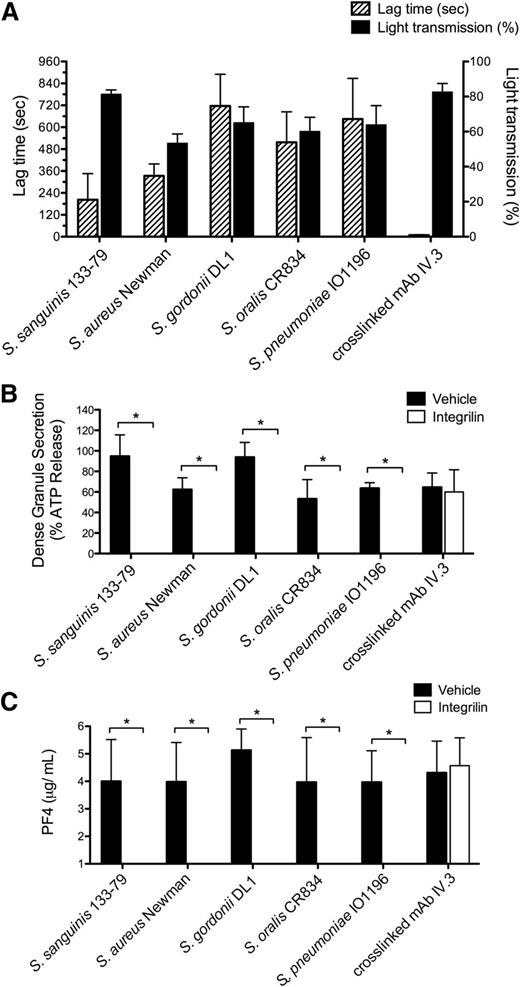

In this study, bacteria were used at concentrations that have been optimized previously. All strains stimulated maximal platelet aggregation but with a strain-specific delay that varied from 120 to 900 seconds (Figure 1A). In all cases, aggregation was associated with robust secretion of dense and α-granules as shown by measurement of ATP and PF4, respectively, which is similar in magnitude to that induced by FcγRIIA clustering (Figure 1B-C). Consistent with previous studies,13-17 aggregation was blocked to all stimuli in the presence of the αIIbβ3 antagonist Integrilin (eptifibatide) (supplemental Figure 2A). Unexpectedly, however, dense and α-granule secretion was also inhibited by Integrilin demonstrating that secretion is dependent on αIIbβ3 engagement (Figure 1B-C). In contrast, secretion induced by cross-linked mAb IV.3 was not altered in the presence of Integrilin (Figure 1B-C).

Bacteria stimulate platelet aggregation and secretion in plasma. (A) Characterization of the lag time for onset of aggregation in response to bacteria. Platelet aggregation in response to bacterial strains belonging to 5 different gram-positive species was monitored in plasma by light transmission aggregometry. Final concentrations of bacteria were S sanguinis 133-79, 0.6 × 108 CFU/mL; S aureus Newman, 1 × 108 CFU/mL; S gordonii DL1, 3 × 108 CFU/mL; S oralis CR834, 4 × 108 CFU/mL; S pneumoniae IO1196, 0.7 × 108 CFU/mL. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on platelet dense granule secretion in response to bacteria. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of Integrilin (9 μM) or vehicle; supernatants collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Supernatants were analyzed for ATP release by luciferin-luciferase assay. ATP levels released in 32 μM TRAP-stimulated platelets were used to normalize data. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05. (C) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on platelet PF4 release in response to bacteria. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of Integrilin (9 μM) or vehicle and supernatants collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Levels of soluble PF4 were measured in duplicates by PF4 ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05.

Bacteria stimulate platelet aggregation and secretion in plasma. (A) Characterization of the lag time for onset of aggregation in response to bacteria. Platelet aggregation in response to bacterial strains belonging to 5 different gram-positive species was monitored in plasma by light transmission aggregometry. Final concentrations of bacteria were S sanguinis 133-79, 0.6 × 108 CFU/mL; S aureus Newman, 1 × 108 CFU/mL; S gordonii DL1, 3 × 108 CFU/mL; S oralis CR834, 4 × 108 CFU/mL; S pneumoniae IO1196, 0.7 × 108 CFU/mL. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on platelet dense granule secretion in response to bacteria. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of Integrilin (9 μM) or vehicle; supernatants collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Supernatants were analyzed for ATP release by luciferin-luciferase assay. ATP levels released in 32 μM TRAP-stimulated platelets were used to normalize data. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05. (C) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on platelet PF4 release in response to bacteria. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of Integrilin (9 μM) or vehicle and supernatants collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Levels of soluble PF4 were measured in duplicates by PF4 ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05.

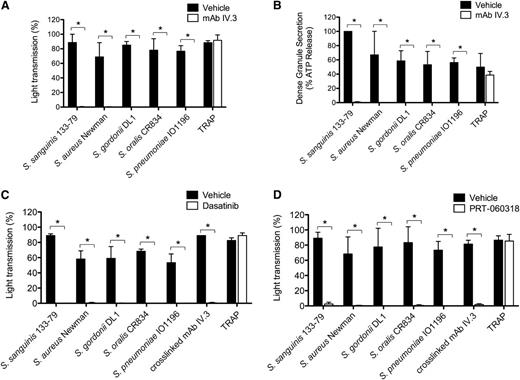

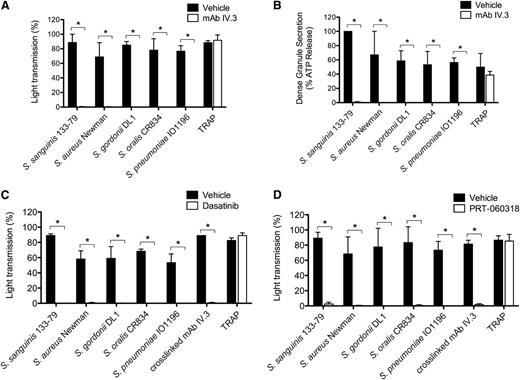

Several studies have reported a critical role for IgG and FcγRIIA in platelet activation by several of the bacteria used in this study.13,15,16,38,39 In line with this, we demonstrate that mAb IV.3 blocks aggregation (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2B) and both dense and α-granule secretion (Figure 2B, and not shown) to the 5 strains, whereas it had no effect on thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP)-induced activation. As FcγRIIA signals through Src and Syk tyrosine kinases, and consistent with a role for FcγRIIA, inhibitors of Src (dasatinib) or Syk (PRT-060318) also abrogated aggregation to all 5 strains (Figure 2C-D; supplemental Figure 2C-D).

FcγRIIA and Src and Syk tyrosine kinases mediate bacteria-induced platelet activation. (A) Effect of anti-FcγRIIA mAb IV.3 on bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. PRP was incubated for 10 minutes with mAb IV.3 (10 μg/mL) or vehicle prior to addition of bacteria or protease-activated receptor 1 agonist TRAP, and platelet aggregation was monitored by light transmission aggregometry (see also supplemental Figure 2B). (B) Effect of anti-FcγRIIA mAb IV.3 on platelet dense granule secretion in response to bacteria. Reactions were performed as in panel A; supernatants were collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Supernatants were analyzed for ATP release by luciferin-luciferase assay. ATP levels released by S sanguinis 133-79–stimulated platelets were used to normalize data. (C) Effect of the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib in bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with dasatinib (4 μM) prior to addition of bacteria or agonists, and platelet aggregation was monitored (see also supplemental Figure 2C). (D) Effect of Syk tyrosine kinase inhibitor PRT-060318 in bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with PRT-060318 (10 μM) or vehicle prior to addition of bacteria or agonist, and platelet aggregation was monitored (see also supplemental Figure 2D). Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05.

FcγRIIA and Src and Syk tyrosine kinases mediate bacteria-induced platelet activation. (A) Effect of anti-FcγRIIA mAb IV.3 on bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. PRP was incubated for 10 minutes with mAb IV.3 (10 μg/mL) or vehicle prior to addition of bacteria or protease-activated receptor 1 agonist TRAP, and platelet aggregation was monitored by light transmission aggregometry (see also supplemental Figure 2B). (B) Effect of anti-FcγRIIA mAb IV.3 on platelet dense granule secretion in response to bacteria. Reactions were performed as in panel A; supernatants were collected at time of full aggregation, or a parallel time point in the case of inhibition. Supernatants were analyzed for ATP release by luciferin-luciferase assay. ATP levels released by S sanguinis 133-79–stimulated platelets were used to normalize data. (C) Effect of the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib in bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with dasatinib (4 μM) prior to addition of bacteria or agonists, and platelet aggregation was monitored (see also supplemental Figure 2C). (D) Effect of Syk tyrosine kinase inhibitor PRT-060318 in bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with PRT-060318 (10 μM) or vehicle prior to addition of bacteria or agonist, and platelet aggregation was monitored (see also supplemental Figure 2D). Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05.

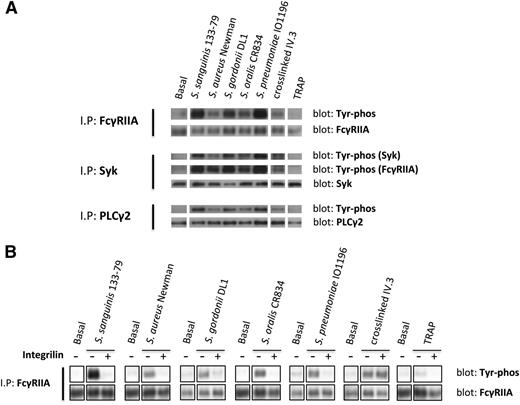

Bacteria-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIA is dependent on αIIbβ3

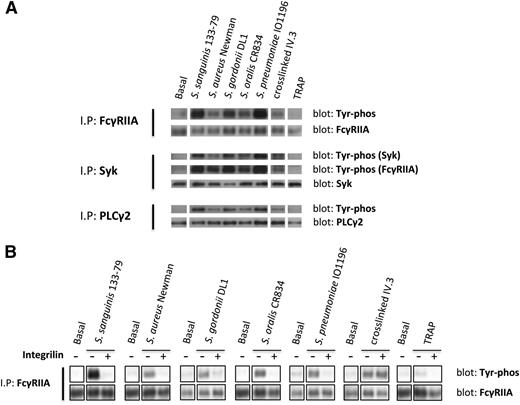

To further investigate the role of FcγRIIA in platelet activation by bacteria, we monitored tyrosine phosphorylation. Because of the high levels of plasma proteins, which mask tyrosine phosphorylation using standard extraction procedures, we used a method that involves removal of plasma proteins prior to cell lysis. We observed marked increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIA and its downstream signaling partners, Syk and PLCγ2, in platelets that had undergone aggregation in response to bacteria or to cross-linked mAb IV.3 (Figure 3A), whereas weak or negligible phosphorylation of FcγRIIA, Syk, and PLCγ2 was detected in lysates from TRAP-induced aggregates (Figure 3A). Although FcγRIIA phosphorylation in response to TRAP has been reported in washed platelets,27 and confirmed by us (not shown), the present results show that FcγRIIA phosphorylation by TRAP is almost undetectable when aggregation is performed in plasma.

Bacteria induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIA that is dependent on αIIbβ3 activation. (A) Tyr phosphorylation of FcγRIIA and downstream mediators during bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. Cell lysates were collected at time of full aggregation; IPs were performed for FcγRIIA, Syk, and PLCγ2. As previously described,37 FcγRIIA coprecipitated during Syk IP and, therefore, phosphorylated Syk and FcγRIIA were detected in the same gel. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on FcγRIIA phosphorylation during bacteria-induced platelet activation. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence or absence of Integrilin (9 μM); cell lysates were collected at time of full aggregation, or equivalent times in the case of Integrilin-treated samples where aggregation was inhibited. IPs for FcγRIIA were performed; tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by western blot. Representative results of 3 independent experiments are shown.

Bacteria induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIA that is dependent on αIIbβ3 activation. (A) Tyr phosphorylation of FcγRIIA and downstream mediators during bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in plasma. Cell lysates were collected at time of full aggregation; IPs were performed for FcγRIIA, Syk, and PLCγ2. As previously described,37 FcγRIIA coprecipitated during Syk IP and, therefore, phosphorylated Syk and FcγRIIA were detected in the same gel. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor Integrilin on FcγRIIA phosphorylation during bacteria-induced platelet activation. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence or absence of Integrilin (9 μM); cell lysates were collected at time of full aggregation, or equivalent times in the case of Integrilin-treated samples where aggregation was inhibited. IPs for FcγRIIA were performed; tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by western blot. Representative results of 3 independent experiments are shown.

Time-course studies were conducted to monitor FcγRIIA phosphorylation. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor was coincident with the onset of platelet aggregation, with no detectable increase prior to this time (not shown). Moreover, FcγRIIA phosphorylation induced by bacteria, but not in response to clustering of mAb IV.3, was blocked in the presence of Integrilin (Figure 3B). Thus, phosphorylation of FcγRIIA by bacteria, like secretion, is dependent on αIIbβ3 engagement.

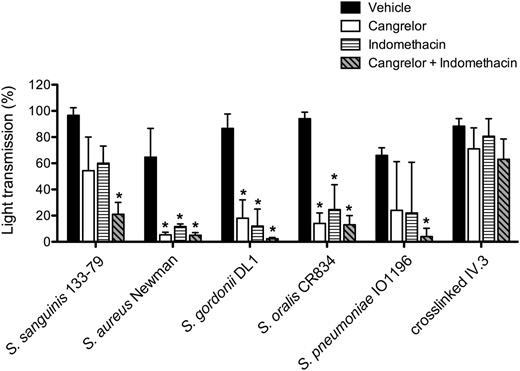

Platelet activation by bacteria is also dependent on ADP and TxA2

Platelet activation is reinforced by release of stored adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) from dense granules and de novo synthesis of thromboxane A2 (TxA2). The P2Y12 antagonist, cangrelor, and cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin, were used to investigate a role for the 2 feedback agonists in bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. Activation was inhibited to varying degrees in the presence of 1 of the 2 inhibitors (Figure 4), but with complete blockade observed in the presence of both inhibitors (Figure 4; supplemental Figure 3). In contrast, response to cross-linked mAb IV.3 was not affected, although deaggregation was observed at later time points (supplemental Figure 3). Thus, platelet activation by bacteria is also dependent on ADP and TxA2.

Secondary mediators TxA2 and ADP are key for bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with COX inhibitor indomethacin (10 μM), ADP-receptor P2Y12 inhibitor cangrelor (1 μM), or vehicle (DMSO) prior to addition of bacteria or cross-linked mAb IV.3, and platelet aggregation was monitored. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05 (see also supplemental Figure 3). DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

Secondary mediators TxA2 and ADP are key for bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. PRP was incubated for 2 minutes with COX inhibitor indomethacin (10 μM), ADP-receptor P2Y12 inhibitor cangrelor (1 μM), or vehicle (DMSO) prior to addition of bacteria or cross-linked mAb IV.3, and platelet aggregation was monitored. Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05 (see also supplemental Figure 3). DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

hIgGs reconstitute aggregation to bacteria in washed platelets

Washed platelets were used to investigate the requirement for plasma components in supporting platelet activation by bacteria. None of the 5 strains induced aggregation in washed platelets, in contrast to the robust response to TRAP and cross-linked mAb IV.3 (not shown). Due to the critical role for FcγRIIA and αIIbβ3 in supporting platelet activation in plasma, we considered whether the absence of IgG and/or fibrinogen could account for this result. In line with this, full aggregation to bacteria in washed platelets was restored in the presence of hIgG (Figure 5). The lag time for aggregation to S aureus Newman, S gordonii DL1, and S oralis CR834 but not to S sanguinis 133-79 was reduced when IgG was added together with fibrinogen, although on its own, fibrinogen alone was unable to restore aggregation to the 4 strains (Figure 5). For S aureus Newman, IgG-depleted fibrinogen was used, as the presence of residual IgGs is sufficient to support aggregation to this strain (Fitzgerald et al40 and not shown). We were unable to consistently restore aggregation to S pneumoniae IO1196 in the presence of IgG and fibrinogen (aggregation was observed in 2 of 5 donors after times >15 minutes), suggesting that other plasma components might be required for robust activation. These results demonstrate that IgG and fibrinogen are required to support bacteria-induced aggregation in washed platelets.

hIgGs reconstitute aggregation to bacteria in washed platelets. Aggregation reactions to S sanguinis 133-79, S aureus Newman, S gordonii DL1, and S oralis CR834 were performed in washed platelets in the presence or absence of fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) and hIgGs (0.1 mg/mL). For S aureus Newman, IgG-depleted fibrinogen was used as previously published.40 One representative reaction of 3 independent experiments per strain is shown.

hIgGs reconstitute aggregation to bacteria in washed platelets. Aggregation reactions to S sanguinis 133-79, S aureus Newman, S gordonii DL1, and S oralis CR834 were performed in washed platelets in the presence or absence of fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) and hIgGs (0.1 mg/mL). For S aureus Newman, IgG-depleted fibrinogen was used as previously published.40 One representative reaction of 3 independent experiments per strain is shown.

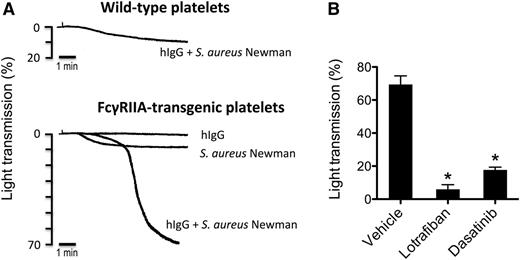

Only S aureus Newman induces aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic mouse platelets

The FcγRIIA receptor is absent in the mouse genome, and mouse platelets do not express an Fc receptor.41 None of the bacterial strains induced aggregation of wild-type mouse platelets in plasma, even in the presence of hIgG (not shown). And, interestingly, only S aureus Newman stimulated platelet aggregation from transgenic mice that express FcγRIIA (Figure 6A, and not shown). Aggregation to S aureus Newman in the transgenic platelets (including endogenous fibrinogen) was strictly dependent on hIgG and was blocked in the presence of the mouse αIIbβ3 antagonist lotrafiban and the Src kinase inhibitor dasatinib (Figure 6B).

S aureus Newman induces aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic mouse platelets. (A) Comparison of FcγRIIA-transgenic vs wild-type mouse platelets in response to S aureus Newman. Aggregation reactions were performed in mouse PRP. Platelets were stimulated with S aureus Newman plus hIgGs (0.5 mg/mL), with S aureus Newman alone or with hIgG alone. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor lotrafiban and Src inhibitor dasatinib on S aureus Newman-induced aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic platelets. Aggregation reactions were performed as in panel A in the presence of 0.5 mg/mL hIgG after platelet preincubation with lotrafiban (10 μM), dasatinib (20 μM), or vehicle (DMSO). Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05.

S aureus Newman induces aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic mouse platelets. (A) Comparison of FcγRIIA-transgenic vs wild-type mouse platelets in response to S aureus Newman. Aggregation reactions were performed in mouse PRP. Platelets were stimulated with S aureus Newman plus hIgGs (0.5 mg/mL), with S aureus Newman alone or with hIgG alone. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Effect of αIIbβ3 inhibitor lotrafiban and Src inhibitor dasatinib on S aureus Newman-induced aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic platelets. Aggregation reactions were performed as in panel A in the presence of 0.5 mg/mL hIgG after platelet preincubation with lotrafiban (10 μM), dasatinib (20 μM), or vehicle (DMSO). Results are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05.

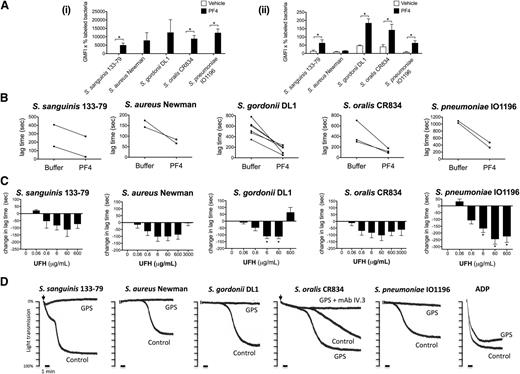

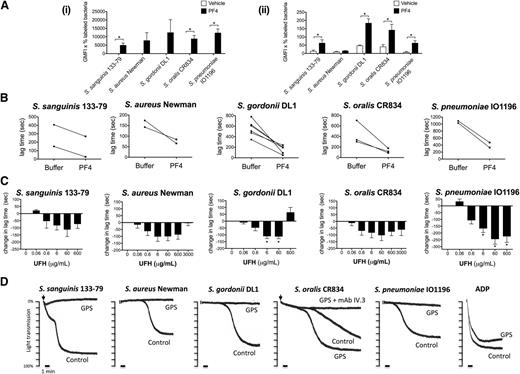

PF4 modulates bacteria-induced platelet aggregation

The platelet α-granule–secreted chemokine PF4 has recently been proposed to have a critical role in the innate defense system by coating bacteria and binding to circulating IgGs, thereby targeting bacteria for phagocytosis.25 To test whether PF4 could also have an effect on bacteria-induced platelet activation, we first measured binding of PF4 to the 5 strains in both buffer and plasma. Marked binding was observed to all strains in buffer (Figure 7Ai) with a much lower level of binding in plasma (Figure 7Aii), most likely due to binding of PF4 to plasma proteins. Indeed, in the case of S aureus Newman, the binding of PF4 in plasma was undetectable.

Bacteria-induced platelet aggregation is modulated by PF4 and heparin and is impaired in GPS platelets. (A) PF4 binding to bacteria. Bacteria were incubated with 20 μg/mL biotinylated human PF4 in buffer (i) or in the presence of 46% plasma from healthy donors (ii). After a secondary incubation with peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5–conjugated streptavidin, PF4 binding was analyzed by flow cytometry (Cytomics FC 500; Beckman Coulter). The GMFI multiplied by the percentage of labeled bacteria constituted binding activity. Results shown are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05. (B) Effect of PF4 on the lag time for onset of bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. Washed platelets were supplemented with fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) and hIgGs (0.1 mg/mL). Purified human PF4 (20 μg/mL) and bacteria were added simultaneously to the platelet preparation and aggregation was recorded (S sanguinis 133-79, n = 2; S aureus Newman, n = 2; S gordonii DL1, n = 6; S oralis CR834, n = 3; S pneumoniae IO1196, n = 2). (C) Effect of heparin on bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of varying doses of UFH: 0.06 μg/mL (0.0125 U/mL), 0.6 μg/mL (0.125 U/mL), 6 μg/mL (1.25 U/mL), 60 μg/mL (12.5 U/mL), 600 μg/mL (125 U/mL), 3000 μg/mL (625 U/mL). UFH was preincubated with platelets for 2 minutes before adding bacteria. Changes in lag time in UFH-treated reactions are presented as the mean ± SEM; *P < .05 (S sanguinis 133-79, n = 6; S aureus Newman, n = 5; S gordonii DL1, n = 6; S oralis CR834, n = 5; S pneumoniae IO1196, n = 6). For S sanguinis 133-79, S gordonii DL1, and S pneumoniae IO1196, 3000 μg/mL UHF inhibited aggregation in all donors (not shown). Lag times (mean ± SD) in the untreated reactions were: S sanguinis 133-79, 273 ± 180 seconds; S aureus Newman, 218 ± 101 seconds; S gordonii DL1, 528 ± 136 seconds; S oralis CR834, 206 ± 82 seconds; S pneumoniae IO1196, 410 ± 152 seconds (see also supplemental Figure 4). (D) Bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in GPS and control platelets. The final platelet concentration in GPS PRP was 1 × 108 platelets per mL and, therefore, the control PRP was diluted in buffer to obtain the same concentration. ADP (30μM) was used as a control agonist for platelet aggregation. Two duplicates were performed per each reaction and sample, and 1 representative trace is shown. Lag times for the reactions shown are: S sanguinis 133-79, 2 minutes; S aureus Newman, 7 minutes 10 seconds; S gordonii DL1, 20 minutes; S oralis CR834, 6 minutes (GPS platelets, 4 minutes); S pneumoniae IO1196, 8 minutes. GMFI, geometric mean fluorescence intensity.

Bacteria-induced platelet aggregation is modulated by PF4 and heparin and is impaired in GPS platelets. (A) PF4 binding to bacteria. Bacteria were incubated with 20 μg/mL biotinylated human PF4 in buffer (i) or in the presence of 46% plasma from healthy donors (ii). After a secondary incubation with peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5–conjugated streptavidin, PF4 binding was analyzed by flow cytometry (Cytomics FC 500; Beckman Coulter). The GMFI multiplied by the percentage of labeled bacteria constituted binding activity. Results shown are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments; *P < .05. (B) Effect of PF4 on the lag time for onset of bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. Washed platelets were supplemented with fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) and hIgGs (0.1 mg/mL). Purified human PF4 (20 μg/mL) and bacteria were added simultaneously to the platelet preparation and aggregation was recorded (S sanguinis 133-79, n = 2; S aureus Newman, n = 2; S gordonii DL1, n = 6; S oralis CR834, n = 3; S pneumoniae IO1196, n = 2). (C) Effect of heparin on bacteria-induced platelet aggregation. Aggregation reactions were performed in plasma in the presence of varying doses of UFH: 0.06 μg/mL (0.0125 U/mL), 0.6 μg/mL (0.125 U/mL), 6 μg/mL (1.25 U/mL), 60 μg/mL (12.5 U/mL), 600 μg/mL (125 U/mL), 3000 μg/mL (625 U/mL). UFH was preincubated with platelets for 2 minutes before adding bacteria. Changes in lag time in UFH-treated reactions are presented as the mean ± SEM; *P < .05 (S sanguinis 133-79, n = 6; S aureus Newman, n = 5; S gordonii DL1, n = 6; S oralis CR834, n = 5; S pneumoniae IO1196, n = 6). For S sanguinis 133-79, S gordonii DL1, and S pneumoniae IO1196, 3000 μg/mL UHF inhibited aggregation in all donors (not shown). Lag times (mean ± SD) in the untreated reactions were: S sanguinis 133-79, 273 ± 180 seconds; S aureus Newman, 218 ± 101 seconds; S gordonii DL1, 528 ± 136 seconds; S oralis CR834, 206 ± 82 seconds; S pneumoniae IO1196, 410 ± 152 seconds (see also supplemental Figure 4). (D) Bacteria-induced platelet aggregation in GPS and control platelets. The final platelet concentration in GPS PRP was 1 × 108 platelets per mL and, therefore, the control PRP was diluted in buffer to obtain the same concentration. ADP (30μM) was used as a control agonist for platelet aggregation. Two duplicates were performed per each reaction and sample, and 1 representative trace is shown. Lag times for the reactions shown are: S sanguinis 133-79, 2 minutes; S aureus Newman, 7 minutes 10 seconds; S gordonii DL1, 20 minutes; S oralis CR834, 6 minutes (GPS platelets, 4 minutes); S pneumoniae IO1196, 8 minutes. GMFI, geometric mean fluorescence intensity.

We then monitored the effect of PF4 on the lag time to activation. Addition of PF4 (20 μg/mL) to washed platelets in the presence of IgG and fibrinogen reduced the time to onset of aggregation for the 5 strains (Figure 7B), although PF4 alone had no effect on its own (not shown).

PF4 (3-100 μg/mL) had no significant effect on bacteria-induced platelet activation in plasma (not shown), which again may reflect the high level of binding to plasma proteins. This observation does not exclude a possible role in supporting bacterial activation of platelets, when a high local PF4 concentration might induce significant binding to bacteria. To investigate this, we used heparin, which binds with high affinity to PF442 and forms multimolecular PF4/heparin complexes that at optimal molar ratios promote PF4 adhesion to platelets43 and bacteria (K.K. and A.G., unpublished observation), as well as platelet activation by HIT antibodies.24,43,44 At concentrations up to 60 μg/mL, heparin reduced the lag time of aggregation to all 5 strains of bacteria in plasma, whereas at higher concentrations the effect was strain-specific, ranging from a reduction or increase in lag time, or abolition of response (Figure 7C; supplemental Figure 4A). Heparin had no effect on platelet aggregation either on its own or on TRAP-induced aggregation at any of the concentrations used in this study (supplemental Figure 4B-C). The dose-dependency of the effect of heparin on platelet activation is similar to that seen in HIT serum, with low concentrations inducing activation and higher concentrations causing abolition of response.

α-granule–deficient platelets do not respond to most bacteria

We used platelets from a patient with GPS, who lacks platelet α-granules, to further investigate a possible role for PF4 in platelet activation to bacteria. Because GPS is associated with a mild thrombocytopenia, these studies were performed with a lower platelet count of 1 × 108/mL, alongside a control with diluted plasma. Whereas all strains induced robust aggregation in the control, only S oralis CR834 induced aggregation of GPS platelets and this was blocked by mAb IV.3, confirming its dependency on FcγRIIA (Figure 7D). These data support a role for α-granule secretion in supporting platelet activation to 4 of the 5 strains.

Discussion

The 5 gram-positive bacterial strains included in this study belong to different species and are known to interact with platelets using strain-specific interactions as outlined in the Introduction. We have performed a systematic comparison of the 5 bacteria and found that they also share a common pathway of platelet activation that involves FcγRIIA activation of Src and Syk kinases and that this is reinforced by αIIbβ3 engagement and granule secretion (supplemental Figure 5). This puts previous observations of a potential role for FcγRIIA in platelet activation13,15,16,38,39 into a new context: FcγRIIA is likely a central pathway involved in bacteria host interaction in humans. Furthermore, this is the first study demonstrating that FcγRIIA- and αIIbβ3-dependent α- and dense granule secretion is important for bacteria-induced platelet aggregation.

Regulation of FcγRIIA phosphorylation by bacteria is distinct from that mediated by direct cross-linking of the receptor. Cross-linking of the anti-FcγRIIA mAb IV.3 induces powerful aggregation and secretion with no discernible delay in response. Activation is associated with marked phosphorylation of FcγRIIA and is independent of αIIbβ3 engagement. In contrast, platelet aggregation induced by our 5 bacteria is associated with a lag phase, and FcγRIIA phosphorylation is dependent on αIIbβ3 engagement. This is similar to S sanguinis strain 2017-78, in which αIIbβ3 engagement is required for sustained FcγRIIA phosphorylation.45 Moreover, bacteria-induced aggregation requires release of ADP and TxA2, and, for 4 of the 5 strains, α-granule secretion. The involvement of these feedback pathways accounts for the “all-or-nothing” nature of platelet activation by bacteria, with FcγRIIA playing a critical role in both the initiation of activation and the feedback response. In this respect, bacteria-induced aggregation is different from that mediated by typical platelet agonists like TRAP. FcγRIIA can function as a membrane adaptor that amplifies the activation of Src/Syk kinases by integrin αIIbβ3 independent of IgG.27,28 However, this mechanism alone cannot account for the level of phosphorylation of FcγRIIA observed in response to bacteria, as aggregation caused by TRAP induces a much lower level of FcγRIIA phosphorylation in plasma. Thus, αIIbβ3 engagement per se does not lead to robust FcγRIIA phosphorylation.

We propose that, after binding of bacteria to the platelet surface through a variety of strain-specific pathways, the initiating event in activation is engagement of FcγRIIA by plasma IgG bound to bacteria, as activation is reconstituted in washed platelets in the presence of IgG. The inability to detect FcγRIIA tyrosine phosphorylation in the absence of αIIbβ3 engagement reflects the weak nature of this pathway of activation in the absence of feedback signals. In turn, FcγRIIA reinforces activation through a pathway that is dependent on αIIbβ3 engagement and granule secretion. The mechanism by which initial activation of αIIbβ3 takes place is likely to be strain-specific. For most bacteria, inside-out activation of αIIbβ3 might be achieved by FcγRIIA signaling, as well as by signaling from other strain-specific interactions. However, some bacteria such as S gordonii DL1 and S aureus Newman have surface proteins that bind to αIIbβ3, which could facilitate αIIbβ3 activation.4,18,46,47 Moreover, S aureus Newman ClfA/B is known to bind to fibrinogen and hIgG simultaneously, which then leads to cross-linking of αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIA.4,46,47 In this way, ClfA/B might engage a strong cooperation between these receptors. This could explain why this strain induces aggregation of FcγRIIA-transgenic mouse platelets, in which cooperation between the 2 receptors has been reported.28 The absence of FcγRIIA-transgenic platelet aggregation to the other bacteria might be due to poor conservation of the strain-specific molecular interactions that are required to facilitate subsequent FcγRIIA-mediated activation.

In all cases, FcγRIIA and αIIbβ3 engagement results in a weak signal leading to release of ADP, TxA2, and PF4. At this stage, feedback mechanisms are key in order to achieve full activation and aggregation. In 4 of 5 strains, activation is reinforced by a pathway that depends on α-granule secretion as shown by the lack of aggregation in GPS platelets. Based on literature on leukocyte recognition of antibodies against PF4/bacteria complexes,25,26 we propose that PF4/bacteria complexes could also contribute to platelet activation. Indeed, the addition of PF4 reduced the lag time of aggregation, although only in a plasma-free system supplemented with fibrinogen and IgG. The absence of a similar observation in plasma may reflect the high level of binding of PF4 to plasma proteins. However, indirect evidence in support of this is the demonstration in plasma that heparin reduces the lag time to activation whereas at higher concentrations this effect is lost or reversed, in a similar way to its effect on platelet activation by HIT antibodies.24,43,44 Consistently, it has been described that platelet activation assays for HIT diagnosis using washed platelets are more sensitive than assays using PRP.48 There are several potential mechanisms through which PF4 could reinforce bacteria-induced platelet activation such as reinforcement of FcγRIIA signaling by bacteria-bound PF4/IgG complexes, synergy with direct interaction of PF4 with platelet receptors, or charge interactions promoting bacteria-platelet cell contact. In this context, ADP/TxA2 might still contribute to activation by reinforcing inside-out αIIbβ3 activation and α-granule secretion leading to a strong positive feedback cascade. For S oralis, α-granule secretion is not mandatory for aggregation, which suggests that it is using ADP/TxA2 very efficiently to feedback on αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIA activation without requirement for PF4. The ways in which bacteria use FcγRIIA to mediate activation are summarized in supplemental Figure 5.

For all strains, aggregation depends on ADP/TxA2 mediating αIIbβ3 inside-out activation in the neighboring (bacteria-free) platelets. Therefore, the release of secondary mediators starts a process in which αIIbβ3 activation and release of ADP/TxA2 feedback on each other. During aggregation, FcγRIIA signaling is likely being reinforced as a consequence of αIIbβ3 engagement and contributes to a cooperative integrin/immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif signaling.27,28

In summary, in this study we provide evidence that bacteria induce activation of platelets through strain-specific interactions and a common pathway that involves FcγRIIA and αIIbβ3 engagement and granule secretion. The demonstration of a common mode of activation identifies FcγRIIA as a candidate receptor for prevention of bacterial-mediated platelet activation in thrombotic-related disorders.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gillian Lowe (University of Birmingham) and the UK GAPP Study Group for providing with a GPS sample. We thank Portola for the gift of PRT-060318.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG/10/88/28628).

Authorship

Contribution: M.A. and K.K. designed and performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; D.O.T. and C.W. performed assays and discussed the results; A.G. and D.C. contributed to the study design and discussed the results; S.W.K. and S.P.W. designed and supervised the research; and all authors read and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mònica Arman, Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Research, School of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Wolfson Dr, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: m.arman@bham.ac.uk; and Steve P. Watson, Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Research, School of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Wolfson Dr, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: s.p.watson@bham.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

S.W.K. and S.P.W. share senior authorship.