To the editor:

In a recent issue of Blood, Agrawal-Singh et al reported the identification of PRDX2 (peroxiredoxin 2) as a novel tumor suppressor gene in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 The authors observed recurrent histone H3 deacetylation and DNA hypermethylation at the PRDX2 promoter region in primary leukemia samples. Epigenetic alterations correlated with low expression of PRDX2 protein and were associated with poor prognosis in AML patients. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that this gene acts as a growth inhibitor in myeloid cells. Here, we provide evidence that PRDX2 methylation and transcriptional silencing is recurrent not only in AML but also in classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), further emphasizing the importance of loss of this tumor suppressor in hematologic malignancies.

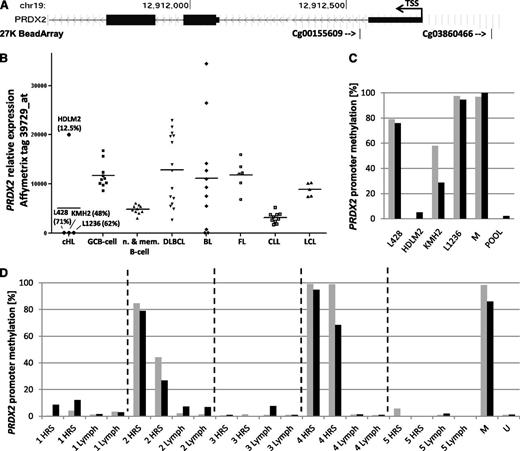

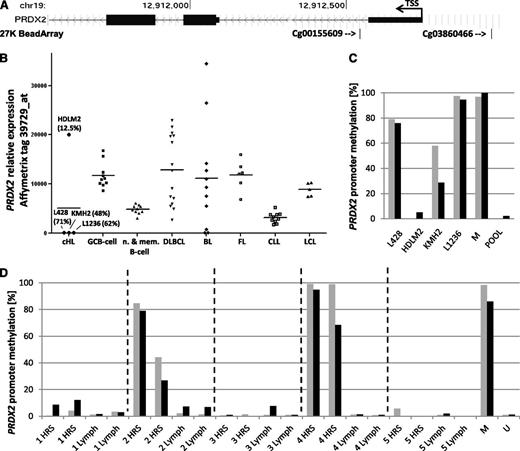

By analyzing methylation profiles of 5 cHL cell lines (27K BeadArray; Illumina),2 we observed hypermethylation of the PRDX2 gene compared with normal B-cell populations, including germinal center B (GCB) cells and a lymphoblastoid B-cell line. Elevated PRDX2 methylation was present in cHL cell lines L428, KMH2, L1236, and UHO1, but not HDLM2, and was indicated by tags flanking the PRDX2 transcription starting site (TSS) (cg03860466, –217 bp from TSS; cg00155609, +196 bp from TSS) (Figure 1A). As observed in AML, elevated methylation correlated with lack of PRDX2 messenger RNA (mRNA) in the cHL cell lines (Figure 1B). In contrast, expression was present in germinal center, naive, and memory B cells and other lymphoma and leukemia specimens (except 3/11 Burkitt lymphomas) showing consistent expression of PRDX2 in normal B-cell populations and the majority of other hematologic malignancies (Figure 1B).3 This is consistent with the observation that the PRDX2 promoter region is rich in motifs recognized by transcription factors widely expressed in B cells, including PAX5, ELF1, TCF4, OCT-1, and nuclear factor κB.4 Together, these findings suggest epigenetic silencing as the mechanism responsible for the downregulation of PRDX2 in cHL (Figure 1B).

Promoter hypermethylation and lack of PRDX2 expression in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells. (A) Localization of the 27K BeadArray (Illumina) array tags cg03860466 and cg00155609 (indicated by arrows) with respect to the PRDX2 TSS. (B) PRDX2 mRNA expression (Affymetrix U95 microarray, tag 39729_at) in cHL cell lines, normal B-cell populations (10 × GCB cells, 5 × naive B cells, 5 × memory B cells), 15 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs), 11 Burkitt lymphomas (BLs), 6 follicular lymphomas (FLs), 11 B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias (CLLs), and 5 large cell lymphomas (LCLs). Mean PRDX2 promoter methylation level based on 27K BeadArray (Illumina) array (tags: cg03860466, cg00155609) in the cHL cell lines is given in parentheses. Methylation and expression data were taken from Ammerpohl et al2 and Küppers et al,3 respectively. (C) Bisulfite pyrosequencing of PRDX2 promoter region in cHL cell lines. Bars represent the cytosine guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites analyzed within the sequenced region (genomic position of the CpG sites: black bar, chr19:12912528; gray bar, chr19:12912542). No bar indicates a methylation level of 0%. (D) Bisulfite pyrosequencing of PRDX2 promoter region in microdissected HRS cells (nodular sclerosis, cases 1, 2, 4, 5; mixed cellularity, 3) and nontumoral bystander cells (Lymph) (in duplicate) (genomic position of the CpG sites: black bar, chr19:12912528; gray bar, chr19:12912542). No bar indicates a methylation level of 0%. M, methylated DNA control (Millipore); POOL, whole blood DNAs, pooled; U, unmethylated DNA control (whole genome amplified DNA).

Promoter hypermethylation and lack of PRDX2 expression in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells. (A) Localization of the 27K BeadArray (Illumina) array tags cg03860466 and cg00155609 (indicated by arrows) with respect to the PRDX2 TSS. (B) PRDX2 mRNA expression (Affymetrix U95 microarray, tag 39729_at) in cHL cell lines, normal B-cell populations (10 × GCB cells, 5 × naive B cells, 5 × memory B cells), 15 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs), 11 Burkitt lymphomas (BLs), 6 follicular lymphomas (FLs), 11 B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias (CLLs), and 5 large cell lymphomas (LCLs). Mean PRDX2 promoter methylation level based on 27K BeadArray (Illumina) array (tags: cg03860466, cg00155609) in the cHL cell lines is given in parentheses. Methylation and expression data were taken from Ammerpohl et al2 and Küppers et al,3 respectively. (C) Bisulfite pyrosequencing of PRDX2 promoter region in cHL cell lines. Bars represent the cytosine guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites analyzed within the sequenced region (genomic position of the CpG sites: black bar, chr19:12912528; gray bar, chr19:12912542). No bar indicates a methylation level of 0%. (D) Bisulfite pyrosequencing of PRDX2 promoter region in microdissected HRS cells (nodular sclerosis, cases 1, 2, 4, 5; mixed cellularity, 3) and nontumoral bystander cells (Lymph) (in duplicate) (genomic position of the CpG sites: black bar, chr19:12912528; gray bar, chr19:12912542). No bar indicates a methylation level of 0%. M, methylated DNA control (Millipore); POOL, whole blood DNAs, pooled; U, unmethylated DNA control (whole genome amplified DNA).

Encouraged by these results, we designed a bisulfite pyrosequencing assay to measure DNA methylation at 2 CpG sites (chr19:12912528 corresponding to the cg00155609 array tag and chr19:12912542) in the 5′ region of PRDX2. The sequenced region encompassed the position chr19:12 912 503-12 912 544 (hg19) (forward primer: 5′-GGTTTAGGGTTTATTTGG-3′; reverse primer: biotin-5′-CCACCAACACTAAAATCAA-3′; sequencing primer: 5′-TGTTTAAGTAGGTATGAATA-3′). The assay was validated on cHL cell lines showing similar methylation levels of PRDX2 as measured by the microarray (Figure 1C).

We applied the assay to primary HRS cells from cHL patients. Because HRS cells constitute usually ∼1% of the cellular infiltrate in an affected lymph node, we used laser microdissection to obtain a pure population of HRS cells. For each patient, 200 HRS cells, 200 nontumoral bystander cells, and a membrane control were microdissected. DNA extracted from these samples was bisulfite converted and pyrosequenced, including methylated and nonmethylated technical controls. Samples from 5 patients were analyzed in duplicate.

In 2 patients (#2 and #4), we indeed observed hypermethylation of the PRDX2 promoter region in microdissected HRS cells compared with corresponding bystander cells (Figure 1D). This demonstrates that PRDX2 is recurrently hypermethylated in primary HRS cells and provides a rationale for our observation based on U133 plus 2.0 expression profiles that primary microdissected HRS cell populations (n = 12) show a 0.58-fold downregulation of PRDX2 expression compared with GCB cells (n = 10).5

Under physiological conditions, PRDX2 scavenges reactive oxygen species modulating their intracellular levels.6 Interestingly, we recently reported that genetic as well as epigenetic alterations in cHL frequently target genes related to reactive oxygen species homeostasis, putatively contributing to loss of B-cell identity and survival of HRS cells.7 Here we propose PRDX2 as a new player among these genes. Moreover, our results suggest epigenetic silencing of this gene in cHL extending the findings by Agrawal-Singh et al.1

Authorship

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a grant from the Polish National Science Centre (2011/01/D/NZ2/00095); the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant GRK1431); the Kinderkrebsinitiative Buchholz/Holm-Seppensen, infrastructure (R.S.); the Federation of Biochemical Societies, long-term fellowship (M.G.) and short-term fellowship “Collaborative Experimental Scholarships for Central and Eastern Europe” (M. Szaumkessel); the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, “Support for International Mobility of Scientists” fellowship (M.G.); and a European Molecular Biology Organization, short-term fellowship (M. Szaumkessel).

Contribution: M. Schneider and M. Szaumkessel performed research; J.R. and O.A. designed experiments; M.-L.H. contributed analytical tools and samples; R.K. provided gene expression data and revised the manuscript; R.S. analyzed data and wrote parts of the manuscript; and M.G. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote parts of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Maciej Giefing, Institute of Human Genetics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Strzeszyńska 32, 60-479 Poznań, Poland; e-mail: giefingm@man.poznan.pl.

References

Author notes

M. Schneider and M. Szaumkessel contributed equally to this study.