Abstract

With the use of ChIP on microarray assays in primary leukemia samples, we report that acute myeloid leukemia (AML) blasts exhibit significant alterations in histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac) levels at > 1000 genomic loci compared with CD34+ progenitor cells. Importantly, core promoter regions tended to have lower H3Ac levels in AML compared with progenitor cells, which suggested that a large number of genes are epigenetically silenced in AML. Intriguingly, we identified peroxiredoxin 2 (PRDX2) as a novel potential tumor suppressor gene in AML. H3Ac was decreased at the PRDX2 gene promoter in AML, which correlated with low mRNA and protein expression. We also observed DNA hypermethylation at the PRDX2 promoter in AML. Low protein expression of the antioxidant PRDX2 gene was clinically associated with poor prognosis in patients with AML. Functionally, PRDX2 acted as inhibitor of myeloid cell growth by reducing levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in response to cytokines. Forced PRDX2 expression inhibited c-Myc–induced leukemogenesis in vivo on BM transplantation in mice. Taken together, epigenome-wide analyses of H3Ac in AML led to the identification of PRDX2 as an epigenetically silenced growth suppressor, suggesting a possible role of ROS in the malignant phenotype in AML.

Introduction

Epigenetic alterations in acute leukemias include aberrant promoter DNA methylation and altered histone modifications, especially histone deacetylation with effects on gene expression.1,2 Studies suggested an intimate communication and mutual dependence between histone acetylation and DNA methylation in the process of gene silencing.3,4 The potential importance of these changes is highlighted by the promising activity of drugs that target epigenetic alterations in leukemia.5 Several drugs that inhibit DNA methylation such as the nucleoside analogues 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (AZA) are in clinical use, and antisense oligonucleotide MG98 that down-regulates DNMT1 has been used in phase 1 clinical trials.6-8 In addition, histone deactelyase inhibitors (HDAC-Is) are currently being tested in clinical trials in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.9 All these studies highlight the importance of aberrant epigenetic alterations in leukemia pathogenesis. However, information remains limited for global changes in the epigenome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

ChIPs followed by DNA microarrays (ChIP-Chip) or deep sequencing have been applied to cell lines and cells from healthy donors.10 Recently, we have used the ChIP-Chip method to identify global changes of the histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in primary blast cells derived from patients with acute leukemia.11 In the present report, patterns of histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac) were analyzed by ChIP-Chip in a large cohort of patients with AML and controls, to identify epigenetic alterations in AML.

Here, we report a widespread loss of H3 acetylation at several loci in the AML epigenome. In addition, we identified a novel tumor suppressor gene PRDX2 that was silenced by epigenetic mechanisms as loss of H3 acetylation and DNA hypermethylation at the promoter in AML. The expression of PRDX2 was reduced in AML. Peroxiredoxins (PRDXs) constitute a family of proteins that functions as antioxidants in cells.12 Reactive oxygen species (ROSs) are generated in cells during several normal physiologic processes, but they are immediately inactivated by enzymatic or nonenzymatic antioxidants. The balance between ROS production and its inactivation is a critical process to prevent oxidative damage inside the cell. Imbalance in ROS levels can initiate cancer because of increases in DNA mutations, causing genomic instability and/or enhanced signal transduction because of, for example, inhibition of protein phosphatases or direct influence on kinases such as p38 and RAS-MAPK.13,14

By scavenging ROSs, PRDXs protect cells from oxidative damage to genomic DNA, lipids, and proteins and regulate normal cellular signaling by modulating intracellular levels of ROSs.12 It has been shown that PRDX2 protects red blood cells from oxidative stress.15 By virtue of its role in maintaining the redox state in vivo, PRDX2 is a regulator of growth factor–induced signaling.16 However, its involvement in the growth of hematopoietic cells and role as a tumor suppressor in acute leukemias has not been studied so far.

Methods

Patient material

Blasts from patients with AML (n = 72) were obtained at the time of diagnosis (in a few cases at first relapse). CD34+ progenitor cells (n = 16) and white blood cells (n = 17) were used as controls. Written informed consent was received from all patients and normal subjects before inclusion in the study. Genomic DNA from BM samples obtained for diagnostic reasons from patients with AML or nonmalignant diseases were isolated with the use of standard procedures. Patient information is provided in supplemental Table 3 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

ChIP-Chip procedure

Microarray data analysis

Cell culture and materials

The 32D cell line (the murine IL-3–dependent myeloid progenitor cell line) was cultured, and cells overexpressing Prdx2 were generated as described.18 U937 cells were cultured, and treatment with AZA was done as described previously.19 For Prdx2 knockdown in 32D cells, shRNA oligos were cloned into p-Super-retro puro vector (Oligoengine), and cells were infected with retrovirus produced in PlateE cells as described later. Cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/mL) and used for subsequent experiments.

Abs for Western blot analysis against Prdx1 (Abcam Inc), Prdx2 (Upstate/Millipore), Prdx3, Prdx4 (LabFrontier), Prdx5 (Sigma-Aldrich), phospho ERK, and total ERK (Cell Signaling) or actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used.

Plasmid constructs

Human PRDX2 cDNA cloned into pEntry vector was purchased from Invitrogen (Ultimate ORF clones). PRDX2 cDNA was shuttled into the PMY retroviral destination vector.20 Myc cloned into murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral vector was a kind gift from Dr M. H. Tomasson (Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO).21 To generate MSCV constructs that express both human PRDX2 cDNA and c-Myc, PRDX2 with internal ribosome entry site (IRES) was amplified from PRDX2-PMY vector with the use of primers flanked on both ends with BglII sites. The amplified product was cut with BglII enzyme, purified, and subsequently ligated into BglII-digested MSCV–c-Myc vector. Clones were confirmed by sequencing.

Mice

Wild-type Balb/c mice (5-6 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River for BM transplantation (BMT) experiments. All animals were housed under pathogen-free conditions, and all experiments were approved by the regulatory authorities.

Preparation of retroviruses

The PRDX2 retroviral construct was expressed along with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) that was translated 3′ of an IRES in the PMY as well as in MSCV vector. Retroviruses that used PMY, PMY-PRDX2, MSCV-EGFP, MSCV–c-Myc–EGFP, or MSCV-PRDX2–c-Myc–EGFP plasmids were prepared as described previously.20

Primary BM cell isolation, retroviral transduction, and BM transplantation

BM colony assays and replating assays

A total of 5000 transduced cells per dish were seeded in complete methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies). GFP+ colonies (> 50 cells) were counted on day 7. For replating assays, colonies from respective dishes were pooled and washed 2 times with PBS. Cells were counted, and 2000 cells per dish were seeded subsequently in methylcellulose. Photographs were taken with an Olympus camera at magnification lens 2× attached to a phase-contrast inverted microscope.

Results

AML blasts are characterized by widespread loss of H3Ac in core promoter regions

Tumor suppressor genes that are epigenetically silenced are often found to have decreased H3Ac levels. However, no systematic analyses have been performed to identify genes with altered histone acetylation patterns in patients with primary AML.

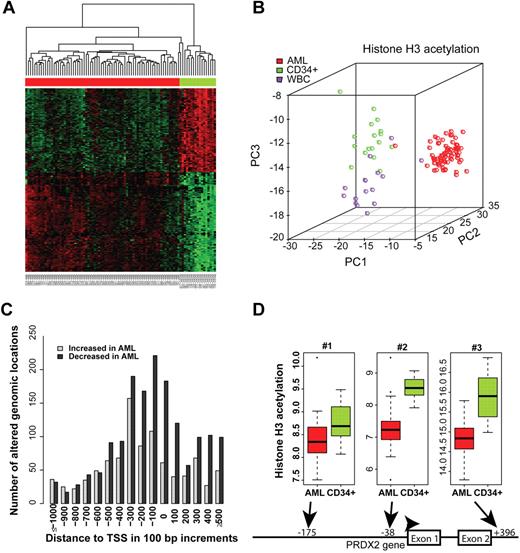

We performed ChIP-Chip–based analyses to identify differences in histone acetylation at the epigenome level with a focus on promoter regions. We analyzed primary AML blast specimens (n = 72) as well as purified CD34+ progenitor cells (n = 17) and white blood cells obtained after granulocyte colony-stimulating factor stimulation (n = 16). Bioinformatic analyses were performed to identify changes in histone acetylation. A comparison of the AML blast specimens and the CD34+ progenitor cells found 2525 genomic loci that significantly differed in their H3Ac intensities at a false discovery rate of 0.05 (corrected for multiple testing). Similarly, 894 loci with different H3Ac intensities between AML blasts and white blood cells were detected (supplemental Table 1). A large proportion of the identified genomic loci in AML was changed similarly compared with CD34+ cells and with white blood cells, indicating a general phenomenon that distinguished AML blasts from hematopoietic cells of various differentiation states. A heat map of genomic regions differing in H3 acetylation indicated specific alterations of chromatin modification patterns in AML that were present across all subtypes (Figure 1A). Examples of loci that showed significant alterations in H3Ac between AML and normal are shown in supplemental Figure 1. A principal component analysis (PCA) clearly separated AML specimens from normal specimens, indicating that distinct patterns of H3 acetylation exist in AML compared with CD34+ progenitors and white blood cells (Figure 1B). A class prediction algorithm accurately predicted the leukemia versus nonleukemia character of the specimens (data not shown). Altogether, these data showed profound differences in H3Ac between leukemia and normal blood cells.

Promoter regions in AML blasts exhibit decreased levels of H3Ac. (A) The top 300 gene-associated genomic regions differing in H3 acetylation patterns between AML (n = 72) and CD34+ progenitors (n = 17) were hierarchically clustered. Green color indicates higher H3Ac levels, whereas red color indicates lower H3Ac levels. AML samples are indicated by the red bar on top of the heat map, and CD34+ progenitors are indicated in green. H3 acetylation of the PRDX2 promoter region is indicated. A full list of differentially acetylated genomic regions is shown in supplemental Table 1. (B) PCA was applied to the top 100 probes with different intensity values between AML, CD34, and white blood cells. Because of the overlap, overall 259 probes were used in the PCA analysis. (C) This histogram depicts the numbers of differentially acetylated regions with respect to their distance from the TSSs. No differences in the frequency of increased versus decreased acetylation levels were observed at distances > 300 bases upstream of the TSS. In contrast, in the core promoter region, losses of H3 acetylation were much more frequent in AML than increases. (D) The PRDX2 promoter was strongly hypoacetylated in AML specimens (n = 71) compared with normal CD34+ cells (n = 17). The probes located at −38 (P = .006) and +396 (P = .014) with regard to the TSS showed significantly lower H3 acetylation even after adjustment for multiple testing of all array probes.

Promoter regions in AML blasts exhibit decreased levels of H3Ac. (A) The top 300 gene-associated genomic regions differing in H3 acetylation patterns between AML (n = 72) and CD34+ progenitors (n = 17) were hierarchically clustered. Green color indicates higher H3Ac levels, whereas red color indicates lower H3Ac levels. AML samples are indicated by the red bar on top of the heat map, and CD34+ progenitors are indicated in green. H3 acetylation of the PRDX2 promoter region is indicated. A full list of differentially acetylated genomic regions is shown in supplemental Table 1. (B) PCA was applied to the top 100 probes with different intensity values between AML, CD34, and white blood cells. Because of the overlap, overall 259 probes were used in the PCA analysis. (C) This histogram depicts the numbers of differentially acetylated regions with respect to their distance from the TSSs. No differences in the frequency of increased versus decreased acetylation levels were observed at distances > 300 bases upstream of the TSS. In contrast, in the core promoter region, losses of H3 acetylation were much more frequent in AML than increases. (D) The PRDX2 promoter was strongly hypoacetylated in AML specimens (n = 71) compared with normal CD34+ cells (n = 17). The probes located at −38 (P = .006) and +396 (P = .014) with regard to the TSS showed significantly lower H3 acetylation even after adjustment for multiple testing of all array probes.

Interestingly, in AML specimens compared with CD34+ cells, genomic locations with decreased H3Ac were much more frequent than regions with increases (Figure 1C). Overall, 1589 genes had lowered acetylation in AML compared with normal CD34+ cells (supplemental Table 1). A closer look at the altered regions showed that the decreases in H3 acetylation levels were centered on the core promoter regions between −300 and the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) and were also present downstream (Figure 1C; P < 10−15). These findings establish the frequent decrease of H3Ac in core promoter regions as an epigenomic signature of AML.

Within the AML specimens, H3 acetylation patterns were not associated with patients' prognosis or with NPM or FLT3-ITD (internal tandem duplication) mutations (data not shown). Specific associations with cytogenetic aberrations could not be adequately tested because relatively few of the AML specimens contained balanced translocations (data not shown).

Genes with lowered H3Ac are DNA methylated at promoters in AML

Genes whose promoters show widespread loss of H3Ac might act as tumor suppressors. We further investigated whether relevant growth suppressors could be identified that were silenced by epigenetic mechanisms. Because several hundred candidate genes were identified by ChIP-Chip, we combined these results with a previous screen that we performed.19 In this study, we showed that mRNA expression of several genes was increased on demethylation by azacytidine, and these genes might act as potential tumor suppressors in AML.19 For the current study, we filtered for genes that were potentially silenced by promoter methylation in the previous study and also showed decreased H3Ac in AML compared with CD34+ samples in our ChIP-Chip arrays. Among 274 genes that were induced on demethylation in leukemia,19 11 genes were significantly altered in both datasets (Table 1). Among these genes, peroxiredoxin-2 (PRDX2) was the most significantly altered gene for histone acetylation and DNA methylation (Table 1). Acetylation at the PRDX2 promoter was significantly decreased in AML compared with CD34+ cells (Figure 1D). These data suggested that PRDX2 might be epigenetically altered by different mechanisms in AML.

Genes silenced by promoter DNA hypermethylation and histone H3 hypoacetylation in AML

| Name . | Symbol . | Gb acc . | Fold change (mRNA) Aza/untreated . | H3 acetylation (log fold change) AML/CD34 . | Adjusted P . | Direction of change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxiredoxin 2 | PRDX2 | L19185 | 2.3075 | −1.3056 | .0059 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Trefoil factor 3 (intestinal) | TFF3 | NM_003226 | 3.1108 | −1.3698 | .0204 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| MHC, class I, A | HLA-A | AI923492 | 2.2161 | −1.2975 | .0137 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| MHC, class I, A | HLA-A | AA573862 | 2.8716 | −1.2975 | .0137 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), delta 1 | CTNND1 | NM_001331 | 2.0985 | −1.0649 | .0291 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | TIMP1 | NM_003254 | 3.5313 | −1.1289 | .0179 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Cylindromatosis (turban tumor syndrome) | CYLD | BF516433 | 2.9026 | −1.0625 | .0286 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Nuclear factor, IL- 3 regulated | NFIL3 | NM_005384 | 2.0471 | −1.0622 | .0403 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 /// TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | TNFSF10 | NM_003810 | 2.4509 | −1.0049 | .0380 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 /// TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | TNFSF10 | NM_003810 | 2.7388 | −1.0049 | .0380 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| ATP-binding cassette, sub-family G (WHITE), member 1 | ABCG1 | NM_004915 | 2.2372 | −1.0052 | .0126 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C | PTPRC | AI809341 | 2.4576 | −0.8651 | .0425 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein like 3 /// SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein like 3 | SH3BGRL3 | NM_031286 | 2.4592 | −1.1272 | .0203 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Name . | Symbol . | Gb acc . | Fold change (mRNA) Aza/untreated . | H3 acetylation (log fold change) AML/CD34 . | Adjusted P . | Direction of change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxiredoxin 2 | PRDX2 | L19185 | 2.3075 | −1.3056 | .0059 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Trefoil factor 3 (intestinal) | TFF3 | NM_003226 | 3.1108 | −1.3698 | .0204 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| MHC, class I, A | HLA-A | AI923492 | 2.2161 | −1.2975 | .0137 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| MHC, class I, A | HLA-A | AA573862 | 2.8716 | −1.2975 | .0137 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), delta 1 | CTNND1 | NM_001331 | 2.0985 | −1.0649 | .0291 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | TIMP1 | NM_003254 | 3.5313 | −1.1289 | .0179 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Cylindromatosis (turban tumor syndrome) | CYLD | BF516433 | 2.9026 | −1.0625 | .0286 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Nuclear factor, IL- 3 regulated | NFIL3 | NM_005384 | 2.0471 | −1.0622 | .0403 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 /// TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | TNFSF10 | NM_003810 | 2.4509 | −1.0049 | .0380 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 /// TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | TNFSF10 | NM_003810 | 2.7388 | −1.0049 | .0380 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| ATP-binding cassette, sub-family G (WHITE), member 1 | ABCG1 | NM_004915 | 2.2372 | −1.0052 | .0126 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C | PTPRC | AI809341 | 2.4576 | −0.8651 | .0425 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

| SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein like 3 /// SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein like 3 | SH3BGRL3 | NM_031286 | 2.4592 | −1.1272 | .0203 | H3Ac in AML decreased |

PRDX2 promoter is DNA hypermethylated and histone H3 hypoacetylated in AML

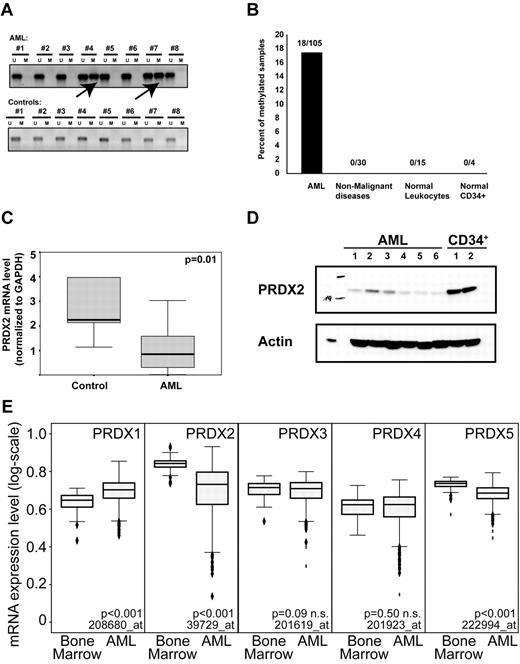

PRDX2 mRNA expression was induced on demethylation in U937 cell lines (Table 1). We analyzed primary AML specimens (n = 109) for PRDX2 promoter methylation by methylation-specific PCR (MSP). As controls we used BM samples from patients with nonmalignant diseases (n = 30), leukocytes from healthy donors (n = 15), and normal CD34+ samples (n = 4). The PRDX2 promoter was specifically methylated in 18% of patients with AML (Figure 2A-B). None of the analyzed controls (n = 49) exhibited DNA methylation at the PRDX2 promoter (P < .001, Fisher exact test). PRDX2 mRNA was consistently decreased in AML blasts compared with normal BM specimens (Figure 2C). PRDX2 protein expression was reduced in AML compared with healthy CD34+ progenitor cells (Figure 2D).

DNA promoter hypermethylation contributes to the epigenetic silencing of the PRDX2 gene in AML. (A) MSP shows promoter methylation in patients with AML no. 4 and no. 7. In total, 105 AML samples and 49 controls (normal BM, nonmalignant controls) were analyzed by MSP. (B) Overall, 18% of the AML samples was methylated at the PRDX2 promoter as analyzed by MSP. No DNA methylation was detected in nonleukemic controls. (C) Low expression of PRDX2 mRNA transcript in AML (n = 61) compared with normal BM specimens (n = 15) as assessed by real-time RT-PCR analysis on BM specimens obtained from patients with AML and healthy persons. Relative gene expression levels were calculated with the use of standard curves with GAPDH being used as internal standard. Statistical analyses were done with SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc), and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the expression levels of PRDX2 between AML and controls (P = .01, Mann-Whitney U test). Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods. (D) Western blot analysis shows reduction of PRDX2 protein levels in primary AML samples compared with normal CD34+ cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (E) The mRNA expression of different PRDX genes was analyzed in a published microarray dataset with 542 AML and 73 nonleukemic BM specimens. P values were calculated with the Mann-Whitney U test. The Affymetrix probe IDs are indicated as well. Two probes of similar quality were present for each PRDX3 and PRDX5. Both led to similar results so only one each was shown in the figure.

DNA promoter hypermethylation contributes to the epigenetic silencing of the PRDX2 gene in AML. (A) MSP shows promoter methylation in patients with AML no. 4 and no. 7. In total, 105 AML samples and 49 controls (normal BM, nonmalignant controls) were analyzed by MSP. (B) Overall, 18% of the AML samples was methylated at the PRDX2 promoter as analyzed by MSP. No DNA methylation was detected in nonleukemic controls. (C) Low expression of PRDX2 mRNA transcript in AML (n = 61) compared with normal BM specimens (n = 15) as assessed by real-time RT-PCR analysis on BM specimens obtained from patients with AML and healthy persons. Relative gene expression levels were calculated with the use of standard curves with GAPDH being used as internal standard. Statistical analyses were done with SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc), and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the expression levels of PRDX2 between AML and controls (P = .01, Mann-Whitney U test). Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods. (D) Western blot analysis shows reduction of PRDX2 protein levels in primary AML samples compared with normal CD34+ cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (E) The mRNA expression of different PRDX genes was analyzed in a published microarray dataset with 542 AML and 73 nonleukemic BM specimens. P values were calculated with the Mann-Whitney U test. The Affymetrix probe IDs are indicated as well. Two probes of similar quality were present for each PRDX3 and PRDX5. Both led to similar results so only one each was shown in the figure.

In a microarray dataset from 542 AML specimens and 73 nonleukemic BM specimens,22 PRDX2 was strongly suppressed in most patients with AML (Figure 2E). In contrast, PRDX1 expression was increased in AML specimens, and PRDX5 was decreased in AML as well but to a lower extent. Further analysis of PRDX2 expression in the microarray dataset showed that PRDX2 expression was significantly repressed in almost all subsets with the exception of AML with complex karyotype (data not shown).

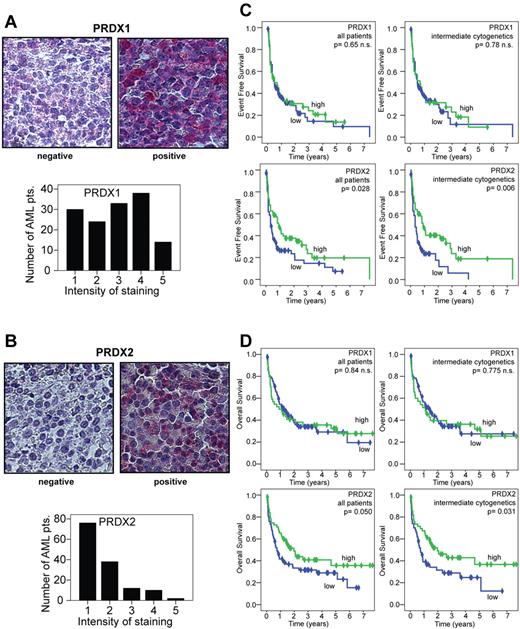

Low protein expression of PRDX2 is associated with poor prognosis in AML

To characterize PRDX2 protein expression in a larger number of patients with AML, we analyzed PRDX2 protein levels in AML BM by IHC. For comparison, we also analyzed PRDX1 protein expression. BM biopsies from 150 patients with AML were prepared as tissue arrays and stained with one anti-PRDX1 and 2 different anti-PRDX2 Abs. Clinical data for the patients are provided in supplemental Table 2. Specificity of Ab staining was verified by staining multiple sections from normal human organs (data not shown). In all cells with positive expression, a clear cytoplasmic staining was observed. Intensity of staining was evaluated with a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating negative expression and 5 indicating very strong staining of all blast cells. The results of the 2 PRDX2 Abs correlated closely (r = +0.64, P < 10−17, Spearman correlation). Further data analyses are therefore shown for one of these Abs. Among AML samples, 56% of AML BM specimens showed no PRDX2 protein expression, whereas PRDX1 was much widely expressed (Figure 3A-B). PRDX1 and PRDX2 expression were correlated (r = +0.39, P < 10−6, Spearman correlation). Similar to the microarray expression patterns, no clear associations were found between PRDX1 or PRDX2 expression and cytogenetic alterations. To analyze whether protein expression was associated with survival, PRDX2 nonexpressing specimens were regarded as low (n = 69) and expressing samples as high (n = 56; Figure 3A-B). Because PRDX1 expression was more widespread, low expression was defined as staining intensity of 1-3 (n = 81) and high as staining intensity of 4-5 (n = 44). Results for PRDX1 did not differ when blasts of patients with absent or very low expression (staining intensity 1) were compared with those with higher expression (data not shown). Distributions of overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) were estimated between AML sample groups according to PRDX1 or PRDX2 expression on the basis of the log-rank test. No significant associations were found for PRDX1 expression and survival (Figure 3C-D top). In contrast, EFS for patients whose blasts lacked PRDX2 expression was significantly shortened: 4.3 months compared with 11 months (P = .028; Figure 3C bottom left). The analyses of OS showed similar results: patients with AML with PRDX2-expressing blasts survived longer than patients with AML with blasts that lacked PRDX2 expression (median survival time, 23.9 vs 9.1; PRDX2+ vs PRDX2−, log-rank Mantel-Cox test, P = .050; Figure 3D bottom left). Because PRDX2 expression did not differ between the cytogenetic AML subgroups, further analyses were performed in patients with intermediate cytogenetics (all with normal karyotype and those without inv(16), t(8;21), t(15;17), complex karyotype, monosomy 7, or trisomy 8). In patients with intermediate cytogenetics, low PRDX2 expression was significantly associated with worse EFS (P = .006) and OS (P = .031; Figure 3C-D right). The long follow-up time of the patients (up to 7 years) allowed us to perform a detailed survival analysis but precluded the analysis of recently identified mutations. A multivariate Cox-regression analysis included PRDX2, age, blood counts (hemoglobin, platelets, white blood cells) at the time of diagnosis, lactate dehydrogenase, primary/secondary AML, and intermediate cytogenetics (yes/no). Overall, 109 patients had values for all these parameters available and were included into the final analyses. PRDX2 expression was a statistically significant prognostic factor in this multivariate analysis (P = .009). In addition, white blood cell count was significant (P = .008). In this limited number of patients, the other well-established prognostic factors did not achieve statistical significance.

Low expression of PRDX2 protein in AML blasts is associated with a poor prognosis. (A) Intensity of PRDX1 staining in tissue arrays from AML BM biopsies. PRDX1 low staining (grade 1-3; left) and positive (grade 4-5; right). AML BM biopsies were analyzed by IHC. (B) Intensity of PRDX2 staining in tissue arrays from AML BM biopsies. PRDX2 low/negative (left) and high (right). AML BM biopsies were analyzed by IHC. Pictures were taken on an Axio Imager M1 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems) with a 63×/1.4 oil objective at room temperature and processed by AxioVision Release 4.5 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems). (C) Kaplan-Meier plots were generated to compare EFS among patients with AML with low or high expression of peroxiredoxins. Results are indicated for the entire patient cohort and for the more homogenous group with intermediate cytogenetics. Patients whose blasts expressed low levels of PRDX2 only experienced worse EFS compared with patients with AML with high expression of PRDX2 (P = .028, log-rank test). In patients with intermediate cytogenetics, low expression of PRDX2 was associated with poor EFS (P = .006). PRDX1 expression levels did not correlate with EFS. (D) Analyses of OS with regard to peroxiredoxin repression. The Kaplan-Meir plots indicate that patients with AML with low PRDX2 expression in leukemic blasts show decreased OS compared with patients with AML with high expressing blasts (P = .050). In patients with intermediate cytogenetics a close association between low expression of PRDX2 in leukemic blasts and poor OS was found (P = .031). PRDX1 expression did not correlate with OS.

Low expression of PRDX2 protein in AML blasts is associated with a poor prognosis. (A) Intensity of PRDX1 staining in tissue arrays from AML BM biopsies. PRDX1 low staining (grade 1-3; left) and positive (grade 4-5; right). AML BM biopsies were analyzed by IHC. (B) Intensity of PRDX2 staining in tissue arrays from AML BM biopsies. PRDX2 low/negative (left) and high (right). AML BM biopsies were analyzed by IHC. Pictures were taken on an Axio Imager M1 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems) with a 63×/1.4 oil objective at room temperature and processed by AxioVision Release 4.5 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems). (C) Kaplan-Meier plots were generated to compare EFS among patients with AML with low or high expression of peroxiredoxins. Results are indicated for the entire patient cohort and for the more homogenous group with intermediate cytogenetics. Patients whose blasts expressed low levels of PRDX2 only experienced worse EFS compared with patients with AML with high expression of PRDX2 (P = .028, log-rank test). In patients with intermediate cytogenetics, low expression of PRDX2 was associated with poor EFS (P = .006). PRDX1 expression levels did not correlate with EFS. (D) Analyses of OS with regard to peroxiredoxin repression. The Kaplan-Meir plots indicate that patients with AML with low PRDX2 expression in leukemic blasts show decreased OS compared with patients with AML with high expressing blasts (P = .050). In patients with intermediate cytogenetics a close association between low expression of PRDX2 in leukemic blasts and poor OS was found (P = .031). PRDX1 expression did not correlate with OS.

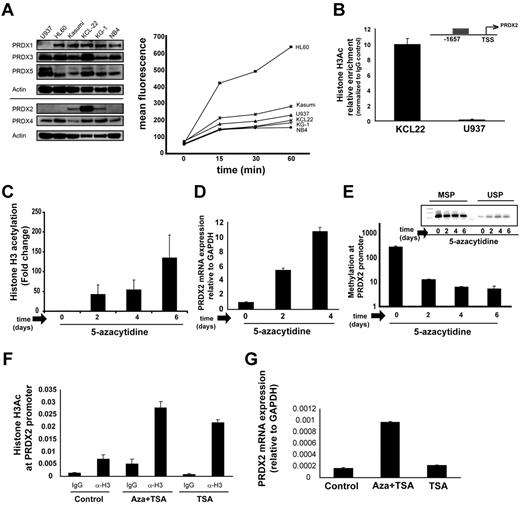

Interplay between DNA methylation and histone acetylation

We examined the expression of different members of the PRDX family in several AML cell lines (Figure 4A). On the basis of differential expression of PRDX2, we selected U937 and KCL22 cells for further studies. To analyze the interdependence of promoter DNA methylation and histone acetylation of the PRDX2 promoter, we exposed U937 cells to 5-azacytidine and analyzed changes in histone acetylation patterns. U937 cells showed decreased levels of histone acetylation at the PRDX2 promoter compared with KCL22 cells, which expressed high levels of PRDX2 (Figure 4A-B). After demethylation of U937 cells by azacytidine for 6 days, H3Ac levels increased significantly at the PRDX2 promoter (Figure 4C). The increase in H3 acetylation correlated with increased mRNA expression of PRDX2 and was associated with a loss of DNA methylation at the PRDX2 promoter after azacytidine treatment (Figure 4D-E).

Interdependence of histone hypoacetylation and DNA hypermethylation at the Prdx2 promoter in AML. (A) Expression of PRDX members in different leukemic cell lines was analyzed by Western blot analysis, showing cell lines with high (KCL22, KG1, Kasumi) and low (U937, HL60, NB4) PRDX2 protein expression. (Right) Induction of ROSs by H2O2 treatment in different leukemic cell lines measured by CM-H2DCFDA dye. (B) H3Ac at the PRDX2 promoter in leukemic cell lines was analyzed by ChIP and real-time PCR with the use of anti-H3Ac Ab. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab are calculated against IgG control with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from triplicate quantitative PCR reactions. The results were verified in ≥ 2 independent biologic experiments. (C) H3Ac was increased at the PRDX2 promoter in U937 cells after 5-azacytidine treatment as analyzed by ChIP. U937 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105/mL with 5-azacytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) at concentration of 100nM. Cells were harvested after 2, 4, and 6 days of treatment for ChIP, RNA, or DNA preparation. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab are calculated against IgG control with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from triplicate quantitative PCR reactions. The results were verified in ≥ 2 independent biologic experiments. (D) PRDX2 mRNA expression was induced after 5-azacytidine treatment in U937 cells as analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Error bars represent SD calculated from 3 independent biologic experiments. Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods. (E) PRDX2 promoter DNA methylation was decreased in the U937 cell line after 5-azacytidine treatment as analyzed by MSP. Nonmethylated promoter (USP) and methylated promoter regions (MSP) were analyzed by PCR. (Inset) Densitometry of the MSP gels indicates a decrease in methylation levels at the PRDX2 promoter after 5-azacytidine treatment in U937 cells. The figure represents the mean ± SD of densitometric values obtained from 3 independent gels. (F) H3Ac at the PRDX2 promoter in U937 cells after treatment with azacytidine in combination with TSA or TSA alone analyzed by ChIP. U937 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105/mL with 5-azacytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 100nM for 3 days followed by addition of TSA (1μM) for 1 hour. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab or IgG were calculated against input with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from duplicate quantitative PCR reactions. (G) PRDX2 mRNA expression was induced after 5-azacytidine treatment or combination of 5-azacytidine and TSA in U937 cells as analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Relative expression was calculated against GAPDH by ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from 2 independent biologic experiments. Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods.

Interdependence of histone hypoacetylation and DNA hypermethylation at the Prdx2 promoter in AML. (A) Expression of PRDX members in different leukemic cell lines was analyzed by Western blot analysis, showing cell lines with high (KCL22, KG1, Kasumi) and low (U937, HL60, NB4) PRDX2 protein expression. (Right) Induction of ROSs by H2O2 treatment in different leukemic cell lines measured by CM-H2DCFDA dye. (B) H3Ac at the PRDX2 promoter in leukemic cell lines was analyzed by ChIP and real-time PCR with the use of anti-H3Ac Ab. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab are calculated against IgG control with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from triplicate quantitative PCR reactions. The results were verified in ≥ 2 independent biologic experiments. (C) H3Ac was increased at the PRDX2 promoter in U937 cells after 5-azacytidine treatment as analyzed by ChIP. U937 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105/mL with 5-azacytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) at concentration of 100nM. Cells were harvested after 2, 4, and 6 days of treatment for ChIP, RNA, or DNA preparation. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab are calculated against IgG control with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from triplicate quantitative PCR reactions. The results were verified in ≥ 2 independent biologic experiments. (D) PRDX2 mRNA expression was induced after 5-azacytidine treatment in U937 cells as analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Error bars represent SD calculated from 3 independent biologic experiments. Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods. (E) PRDX2 promoter DNA methylation was decreased in the U937 cell line after 5-azacytidine treatment as analyzed by MSP. Nonmethylated promoter (USP) and methylated promoter regions (MSP) were analyzed by PCR. (Inset) Densitometry of the MSP gels indicates a decrease in methylation levels at the PRDX2 promoter after 5-azacytidine treatment in U937 cells. The figure represents the mean ± SD of densitometric values obtained from 3 independent gels. (F) H3Ac at the PRDX2 promoter in U937 cells after treatment with azacytidine in combination with TSA or TSA alone analyzed by ChIP. U937 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105/mL with 5-azacytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 100nM for 3 days followed by addition of TSA (1μM) for 1 hour. Enrichments for the H3 acetylation Ab or IgG were calculated against input with the use of the ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from duplicate quantitative PCR reactions. (G) PRDX2 mRNA expression was induced after 5-azacytidine treatment or combination of 5-azacytidine and TSA in U937 cells as analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Relative expression was calculated against GAPDH by ddCt method. Error bars represent SD calculated from 2 independent biologic experiments. Primer sequences are given in the supplemental information for methods.

Next, we investigated the effect of the HDAC-I trichostatin-A (TSA) alone or in combination with azacytidine at the PRDX2 promoter and its expression. U937 cells were incubated with azacytidine for 3 days, followed by 1-hour treatment with TSA. The data showed that TSA induced H3Ac at the PRDX2 promoter (Figure 4F) when used alone or in combination with azacytidine. TSA alone did not influence the PRDX2 gene expression in U937 cells (Figure 4G; supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that DNA methylation is the dominant silencing factor for the PRDX2 gene in U937 cells.

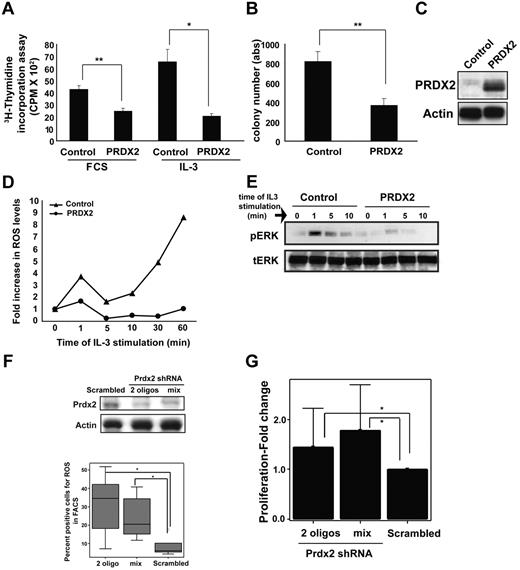

PRDX2 is a myeloid cell growth inhibitor

Epigenetic regulation of the PRDX2 promoter and reduced expression in AML prompted us to analyze the functional relevance of PRDX2 in myeloid cells. First, we analyzed the effects of PRDX2 overexpression on growth of 32D cells. Retrovirally transduced PRDX2 inhibited growth of 32D cells as assessed by proliferation assays and colony-forming assay (P < .01, t test; Figure 5A-B). PRDX2 functions as an antioxidant that regulates the levels of ROSs in cells.15 We investigated whether PRDX2 regulates the ROS level in 32D cells, which were generated because of IL-3 stimulation. Flow cytometric analyses were performed with fluorescent dye to detect ROS concentrations in 32D cells in the presence or absence of PRDX2. IL-3 stimulation induced an exponential increase of ROSs in control cells, whereas PRDX2 expression inhibited this increase of ROSs (Figure 5D). We also observed inhibition of MAP kinase (ERK) phosphorylation in PRDX2-expressing cells compared with vector control cells (Figure 5E). These data indicated that PRDX2 reduced ROS levels and inhibited signaling pathways downstream of IL-3 stimulation. In line with reduced signaling, PRDX2 suppressed the growth of 32D cells (Figure 5B). Similar growth-suppressive effects were observed when 32D cells were exposed to N-acetylcystein, which also functions as an antioxidant (data not shown). PRDX2 did not influence the granulocytic differentiation of 32D cells on granulocyte colony-stimulating factor exposure (data not shown).

PRDX2 inhibits proliferation and clonogenic growth of myeloid cells. (A) The myeloid progenitor cell line 32D was transduced with PRDX2-expressing retrovirus. A total of 2 × 104 32D cells overexpressing Prdx2 were deprived of IL-3 and serum (0.5% FCS) for 12 hours in 200 μL of medium in a 96-well plate. Subsequently, cells were placed in medium with 10% FCS or supplemented with IL-3 (0.1 ng/mL). After an 8-hour incubation period at 37°C, 1μCi (0.037 MBq) 3H-thymidine was added to each well, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 hours. Cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters, and emission of bound DNA was analyzed in a scintillation counter. Cells overexpressing PRDX2 proliferated much slower than the vector control cells as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation assay. The results shown are the mean of triplicates of 3 independent experiments ± SD. The * indicates the significance, calculated by t test; **P < .001 and *P < .05. (B) Colony growth in IL-3–supplemented methylcellulose was reduced in PRDX2-overexpressing 32D cells compared with empty vector control cells. The results represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SD (*P < .001, t test). (C) Expression of PRDX2 in 32D cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis. (D) ROSs were measured by the redox-sensitive fluorochrome Dihydrorhodamine 6G and visualized with flow cytometry. Increases in ROS levels after IL-3 stimulation were observed in control vector-transduced cells but not in PRDX2-expressing 32D cells. The result shown here is a representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) Intracellular signal transduction events were analyzed by Western blot analysis with phosphor-specific or total ERK Ab. Phosphorylation of ERK on IL-3 exposure was inhibited by PRDX2 expression. (F) Prdx2 expression was suppressed by shRNA in murine 32D cells. Sufficient inhibition of Prdx2 protein was achieved with 2 shRNA oligonucleotides or a mix of 3 RNAi sequences. Western blot analysis shows reduction in Prdx2 protein level after shRNA transfection (top panel). ROS levels were increased after shRNA-mediated knockdown of Prdx2 in 32D cells as analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS) with the use of the same probe as described above (bottom). Experiment was biologically repeated 5 times. The significance was calculated with the t test (*P < .05). (G) The decrease of Prdx2 expression enhanced proliferation of 32D cells. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test).

PRDX2 inhibits proliferation and clonogenic growth of myeloid cells. (A) The myeloid progenitor cell line 32D was transduced with PRDX2-expressing retrovirus. A total of 2 × 104 32D cells overexpressing Prdx2 were deprived of IL-3 and serum (0.5% FCS) for 12 hours in 200 μL of medium in a 96-well plate. Subsequently, cells were placed in medium with 10% FCS or supplemented with IL-3 (0.1 ng/mL). After an 8-hour incubation period at 37°C, 1μCi (0.037 MBq) 3H-thymidine was added to each well, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 hours. Cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters, and emission of bound DNA was analyzed in a scintillation counter. Cells overexpressing PRDX2 proliferated much slower than the vector control cells as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation assay. The results shown are the mean of triplicates of 3 independent experiments ± SD. The * indicates the significance, calculated by t test; **P < .001 and *P < .05. (B) Colony growth in IL-3–supplemented methylcellulose was reduced in PRDX2-overexpressing 32D cells compared with empty vector control cells. The results represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SD (*P < .001, t test). (C) Expression of PRDX2 in 32D cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis. (D) ROSs were measured by the redox-sensitive fluorochrome Dihydrorhodamine 6G and visualized with flow cytometry. Increases in ROS levels after IL-3 stimulation were observed in control vector-transduced cells but not in PRDX2-expressing 32D cells. The result shown here is a representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) Intracellular signal transduction events were analyzed by Western blot analysis with phosphor-specific or total ERK Ab. Phosphorylation of ERK on IL-3 exposure was inhibited by PRDX2 expression. (F) Prdx2 expression was suppressed by shRNA in murine 32D cells. Sufficient inhibition of Prdx2 protein was achieved with 2 shRNA oligonucleotides or a mix of 3 RNAi sequences. Western blot analysis shows reduction in Prdx2 protein level after shRNA transfection (top panel). ROS levels were increased after shRNA-mediated knockdown of Prdx2 in 32D cells as analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS) with the use of the same probe as described above (bottom). Experiment was biologically repeated 5 times. The significance was calculated with the t test (*P < .05). (G) The decrease of Prdx2 expression enhanced proliferation of 32D cells. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test).

Two (HL60 and U937) of the 3 leukemic cell lines that expressed very low levels of PRDX2 showed strong induction of ROSs after H2O2 exposure (Figure 4A). The other remaining cell line with low levels of PRDX2 did not show a high degree of ROS induction. This might indicate that other antioxidants can in some cell lines compensate for the loss of PRDX2.

PRDX2-specific shRNA enhanced the growth of 32D cells, which was associated with an increase in ROSs (P < .05, analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test; Figure 5F; data not shown). We also investigated the effects of PRDX2 knockdown on the proliferation of KCL22 cells. The proliferation of KCL22 cells was enhanced by reduction in the amount of PRDX2 levels (supplemental Figure 3).

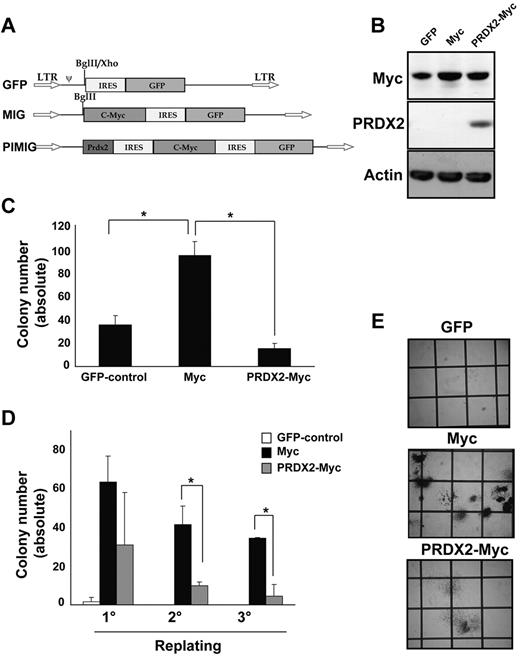

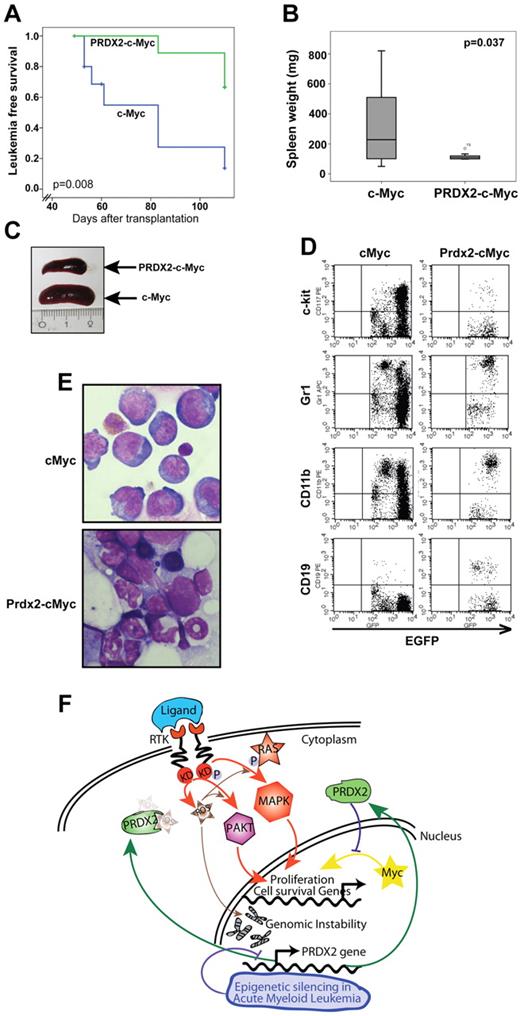

PRDX2 acts as a growth suppressor in leukemogenesis in vivo

We next analyzed whether PRDX2 expression could inhibit oncogene-induced leukemogenesis. Deregulated expression of c-Myc is associated with several malignancies, including leukemia, and induces ROSs.23 Therefore, we selected c-Myc–induced leukemia as a model to investigate PRDX2 tumor suppressor function (Figure 6A). Expression of c-Myc and PRDX2 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 6B). c-Myc levels increased in both c-Myc– or c-Myc-PRDX2–transduced cells compared with empty vector control cells, whereas significant expression of Prdx2 was observed only in c-Myc–PRDX2 cells (Figure 6B). PRDX2 expression reduced the number of colonies (granulocyte CFU) formed by primary BM in the presence of c-Myc (Figure 6C,E). PRDX2 expression also inhibited c-Myc–induced replating of primary BM cells (Figure 6D). To elucidate its function in vivo, we performed BM transplantation in wild-type Balb/c mice with the use of retrovirally transduced primary BM cells with either EGFP or c-Myc–EGFP or PRDX2–c-Myc–EGFP expression. PRDX2 expression prolonged the latency of c-Myc–induced leukemia development (median latency, 65 ± 20 days and 83 ± 10 days for c-Myc and c-Myc–PRDX2, respectively; log-rank Mantel-Cox, P = .008; Figure 7A). Splenomegaly was observed in mice that received a transplant of c-Myc but was diminished in PRDX2-expressing c-Myc mice (Figure 7B-C). We further performed flow cytometric analyses on the BM cells obtained from mice transplanted with either c-Myc-EGFP or PRDX2–c-Myc–EGFP. As shown in Figure 7D, the c-Myc–induced leukemias expressed c-Kit and CD11b, indicative of a myeloid phenotype. Expression of PRDX2 did not alter the myeloid phenotype of the leukemias. BM cytology shown in Figure 7E suggests that PRDX2 expression reduced the number of blast cells observed in mice that received a transplant with c-Myc alone.

PRDX2 expression inhibits c-Myc-induced colony formation in primary murine BM. (A) Design of the retroviral constructs used for transduction of murine BM cells. pMSCV vector backbone with IRES-GFP. c-Myc was cloned in front of IRES-GFP (MIG). PRDX2 was cloned together with second IRES in front of c-Myc (PIMIG). (B) Western blot analyses confirmed the expression of c-Myc and PRDX2 in 32D cells transduced with the indicated retroviral constructs. Actin was used as loading control. (C) PRDX2 overexpression in murine BM cells inhibited the colony growth that was induced because of Myc overexpression. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (GFP vs c-Myc, P = .027; c-Myc vs PRDX2, P = .012, t test). (D) Serial replating indicated the decrease of replicative potential of c-Myc–transduced cells with simultaneous expression of PRDX2. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments (*P < .05, calculated by t test). (E) Photographs taken on day 8 of colony assays showing enhanced colony formation in c-Myc–expressing BM cells. PRDX2 expression together with c-Myc reduced the number of colonies in total. The colonies in c-Myc–PRDX2 appeared as more differentiated colonies from granulocytic/monocytic lineage with more scattered structure, whereas in c-Myc alone, they appeared as colonies from more immature/myeloid progenitor cells.

PRDX2 expression inhibits c-Myc-induced colony formation in primary murine BM. (A) Design of the retroviral constructs used for transduction of murine BM cells. pMSCV vector backbone with IRES-GFP. c-Myc was cloned in front of IRES-GFP (MIG). PRDX2 was cloned together with second IRES in front of c-Myc (PIMIG). (B) Western blot analyses confirmed the expression of c-Myc and PRDX2 in 32D cells transduced with the indicated retroviral constructs. Actin was used as loading control. (C) PRDX2 overexpression in murine BM cells inhibited the colony growth that was induced because of Myc overexpression. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (GFP vs c-Myc, P = .027; c-Myc vs PRDX2, P = .012, t test). (D) Serial replating indicated the decrease of replicative potential of c-Myc–transduced cells with simultaneous expression of PRDX2. The results shown are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments (*P < .05, calculated by t test). (E) Photographs taken on day 8 of colony assays showing enhanced colony formation in c-Myc–expressing BM cells. PRDX2 expression together with c-Myc reduced the number of colonies in total. The colonies in c-Myc–PRDX2 appeared as more differentiated colonies from granulocytic/monocytic lineage with more scattered structure, whereas in c-Myc alone, they appeared as colonies from more immature/myeloid progenitor cells.

PRDX2 inhibits leukemogenesis in Myc-associated BM transplantation model. (A) Primary murine BM was retrovirally transduced with either c-myc alone or with simultaneous PRDX2 expression (PRDX2–c-myc). Similar numbers of transduced BM cells (indicated by GFP expression) were transplanted into lethally radiated recipients. Leukemia development and survival were followed over time. The Kaplan-Meier plots indicate a significantly prolonged latency and less penetrance on PRDX2 expression (P = .008, log-rank test). (B) Weight distribution of spleens of the mice that received a transplant at the time of leukemia development (for PRDX2-Myc animals, > 10 weeks after transplantation). Data shown here are from 10 individual mice analyzed for each group. Significance was calculated by nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Photographic image of spleens of the mice that received a transplant (1 representative mouse from each group) at the time of disease development. (D) Immunophenotype of BM cells obtained from mice that received a transplant with c-Myc or Prdx2–c-Myc analyzed by flow cytometry. BM cells were stained for surface expression of indicated markers, and cells were acquired with BD FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed with CellQuest Version 6.0 software (BD Biosciences). (E) Cytospin structure from mice that received a transplant with c-Myc or Prdx2-c-Myc–transduced BM. Cytospin preparations of BM cells were stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification, ×60). Pictures were taken on an Axio Imager M1 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems) with a 63×/1.4 oil objective at room temperature and processed by AxioVision Release 4.5 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems). (F) Model of the role of ROS and PRDX2 silencing in leukemogenesis. ROS is induced by various mechanisms in leukemogenesis, including cytokine signaling or c-Myc overexpression. Increased ROS levels enhance signaling and lead to increased expression of proliferation and cell survival genes. In addition, ROS levels induce genomic instability. ROS molecules are scavenged by PRDX2, which leads to decreases in signaling and potentially also genomic instability. The frequent epigenetic silencing of PRDX2 in AML can lead to increase in ROS levels and thereby enhanced signaling and proliferative capacity of leukemia cells.

PRDX2 inhibits leukemogenesis in Myc-associated BM transplantation model. (A) Primary murine BM was retrovirally transduced with either c-myc alone or with simultaneous PRDX2 expression (PRDX2–c-myc). Similar numbers of transduced BM cells (indicated by GFP expression) were transplanted into lethally radiated recipients. Leukemia development and survival were followed over time. The Kaplan-Meier plots indicate a significantly prolonged latency and less penetrance on PRDX2 expression (P = .008, log-rank test). (B) Weight distribution of spleens of the mice that received a transplant at the time of leukemia development (for PRDX2-Myc animals, > 10 weeks after transplantation). Data shown here are from 10 individual mice analyzed for each group. Significance was calculated by nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Photographic image of spleens of the mice that received a transplant (1 representative mouse from each group) at the time of disease development. (D) Immunophenotype of BM cells obtained from mice that received a transplant with c-Myc or Prdx2–c-Myc analyzed by flow cytometry. BM cells were stained for surface expression of indicated markers, and cells were acquired with BD FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed with CellQuest Version 6.0 software (BD Biosciences). (E) Cytospin structure from mice that received a transplant with c-Myc or Prdx2-c-Myc–transduced BM. Cytospin preparations of BM cells were stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification, ×60). Pictures were taken on an Axio Imager M1 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems) with a 63×/1.4 oil objective at room temperature and processed by AxioVision Release 4.5 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Systems). (F) Model of the role of ROS and PRDX2 silencing in leukemogenesis. ROS is induced by various mechanisms in leukemogenesis, including cytokine signaling or c-Myc overexpression. Increased ROS levels enhance signaling and lead to increased expression of proliferation and cell survival genes. In addition, ROS levels induce genomic instability. ROS molecules are scavenged by PRDX2, which leads to decreases in signaling and potentially also genomic instability. The frequent epigenetic silencing of PRDX2 in AML can lead to increase in ROS levels and thereby enhanced signaling and proliferative capacity of leukemia cells.

Taken together, the in vivo data suggest that PRDX2 acts as a growth suppressor to slow leukemia induction caused by the c-Myc oncogene.

Discussion

Epigenome characterization of malignant diseases promises insights into disease pathogenesis and new approaches for therapeutic interventions. Histone modifications are of particular interest, given that multiple oncogenes are known to induce changes in posttranslational histone modifications. Histone acetylation and DNA methylation patterns are regarded as heritable marks that ensure the accurate transmission of the chromatin states and gene expression profiles.24 Importantly, these patterns are profoundly altered in hematologic malignancies and other cancers.1,25 Epigenetic therapies such as HDAC-Is have entered clinical use for hematologic malignancies.26,27

Here, we identify loss of H3Ac at core promoter regions as a defining feature that is shared by most if not all AML blasts. An Ab against overall H3Ac was chosen, based on the idea that for histone acetylation its overall levels rather than the acetylation of a single residue correlate most closely with transcriptional activity. Decreases in H3 acetylation were observed in comparison to purified CD34+ progenitor cells and in comparison to white blood cells (supplemental Table 1). CD34+ cells, the progenitor and stem cell populations, and mature white blood cells show similar differences compared with AML blasts, indicating that these changes are unlikely to be differentiation dependent.

Recently, Martens et al described that global acetylation levels are decreased because of PML-RARα binding in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia.28 There might be several other transcription factors that recruit HDAC complexes to the promoter regions in other subtypes of AML. In our analyses, we did not detect a statistically significant association between H3Ac patterns and specific mutations, presumably because of small sample sizes for each type. The origin of the widespread loss of histone acetylation in core promoter regions in AML is unknown. Nonetheless, the presence of mutations in the CBP histone acetyltransferase in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia29 suggests that genetic mutations could also account for histone acetylation changes in AML. The AML blast specimens were stored and analyzed before the knowledge about mutations in DNMT3A, EZH2, Tet2, and IDH1/2 became available. It will be interesting in the future to analyze whether and if yes how these mutations could contribute to altered H3 acetylation patterns in AML.

When we analyzed genes with hypoacetylated promoters, we observed that many of these genes are involved in the regulation of hematopoietic growth and development (data not shown).

We identified 11 genes that were significantly altered for both epigenetic modifications of H3Ac and DNA methylation in AML.19 These genes included PRDX2, which was the most significantly regulated gene for histone acetylation, as well as TFF3, TIMP1, Catenin δ, and TNFSF10. These latter 4 genes have already been reported to be silenced by epigenetic mechanisms in different cancers.30-33 Genes in this class are potentially tumor-suppressor genes that are silenced by epigenetic mechanisms in cancers.

As a proof of principle, we further analyzed the PRDX2 promoter and gene because the corresponding protein regulates ROS levels, and ROS is increasingly recognized as an important contributor to AML pathogenesis.34 We observed that PRDX2 promoter DNA hypermethylation occurred in blasts from a subset of patients with AML but not in healthy controls. Consistent with this observation, histone acetylation, DNA methylation, and gene expression were intimately linked in U937 cells. We observed decreases of PRDX2 expression in several cohorts of patients with AML at the mRNA level and at the protein level. Loss of PRDX2 expression was an independent parameter, predicting a worse outcome in AML. PRDX2 expression did not differ between different subgroups of AML, suggesting that epigenetic silencing of PRDX2 might not be caused by any subtype-specific leukemia-initiating oncoprotein, but it might be because of more general mechanisms.

PRDX2 is a member of the family of peroxiredoxins that regulates ROSs in the cellular environment. ROSs modulate carcinogenesis because of their involvement in cellular metabolic and signaling processes.13,14 Previously, PRDX2 has been shown to negatively influence the signaling of the PDGFR.16 Its expression has been shown to be decreased in melanoma by promoter methylation.35 Another peroxiredoxin gene, PRDX4, was recently shown to be epigenetically repressed specifically in acute promyelocytic leukemia.36 The expression of PRDX1, another member of the PRDX family, was increased in AML in a published microarray dataset.22 In addition, tissue array data showed very strong staining intensity for PRDX1 in AML, but there was no correlation with the survival of patients with AML and high PRDX1 expression. Taken together, PRDX2 is the most differently regulated PRDX gene in AML, and it acts as a tumor suppressor on the basis of its prognostic value in patients with AML and based on in vivo data showing its potential to slow down the oncogenic activity of c-Myc.

Recent studies have shown that ROS plays an important role in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. These studies raise the possibility that it is the abundance of ROSs within the stem cell, rather than in the microenvironment, that contributes to the maintenance of the stem cell state and leukemia development. Consequently, this raises the question of what molecular mechanism controls ROSs in the stem cells. We showed here that the redox-regulating enzyme PRDX2 is suppressed by epigenetic mechanisms in most AML blasts. These findings provide an explanation for the increased levels of ROSs that occur in AML.37,38 In addition, mutant Flt3 receptor tyrosine kinase induces ROSs,39 and the inactivation of PRDX2 in AML might inactivate a negative feedback loop for oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. To explore this possibility, we analyzed our dataset of PRDX2 methylation in patients with AML; we observed one sample with Flt3-ITD mutation that also showed PRDX2 promoter methylation. These findings do not suggest a close link between Flt3-ITD and PRDX2.

We also report PRDX2 inhibits c-Myc–induced leukemogenesis. Expression of c-Myc has been reported to be increased in AML.40 In addition, c-Myc expression in BMT studies induces acute leukemias, supporting the notion that c-Myc is a potential oncogene in leukemia.21 It is known that c-Myc increases ROS levels, which may also be associated with induction of DNA damage by c-Myc.23,41,42 A study reported the association of c-Myc and Prdx in regulating ROS homeostasis.43 With the use of in vivo models, we showed that PRDX2 can delay c-Myc–induced leukemias in mice. These data suggest that PRDX2 might act as a tumor-suppressor gene in acute leukemia. Regulation of ROSs by PRDX proteins seems to be a crucial event for the prevention of tumorigenesis,44 because loss of peroxiredoxin proteins predispose mice to age-dependent malignancies.15,45 Our data support a role for members of the PRDX family as tumor suppressors. Expression of PRDX2 in healthy cells scavenges the H2O2, results in reduced burden of ROS, and prevents cells from oxidative damage. PRDX2 strongly inhibited leukemogenesis on overexpression. The effect was much less pronounced in murine BM cells with Prdx2 deletion. Indeed, Myc-induced leukemogenesis was not altered in murine BM cells that lacked Prdx2 (data not shown).

Given the suppression of PRDX2 in human AML, its silencing by different mechanisms, and its prognostic effect, it is probable that the redundancy with other PRDX proteins mitigated its effects in murine BM. Interestingly, low PRDX2 levels were closely and independently associated with survival of patients with AML. Because survival differences in AML mostly depend on altered treatment response and resistance, it is possible that loss of PRDX2 increases treatment resistance, probably by increased ROS levels. This is in line with studies showing that oxidative stress plays a role in AML relapse.46

In summary, we report that the AML epigenome possesses distinct epigenetic patterns compared with normal cells. Loss of H3Ac at core promoter regions is a hallmark of AML blasts. PRDX2 is frequently silenced by decreased H3 acetylation and DNA hypermethylation in AML. PRDX2 functions as a tumor-suppressor gene in AML, and loss of PRDX2 is associated with a poor prognosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr T. Kitamura for PMY-EGFP vector, Dr Michael H. Tomasson for c-Myc-MSCV vector, Sandra Gelsing and Beate Lindtner for their excellent technical support, and other members of our laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MU1328/8-1and MU1328/9-1), the Deutsche Krebshilfe (108401), the NGFN-Plus (01GS0873), the Innovative Medizinische Forschung (AG110712), and the Interdisziplinären Zentrums fur Klinische Forschung (Mül2/020/11) at the University of Muenster and Danish Research Medical council (FSS project no. 09-073526).

Authorship

Contribution: S.A.-S. and C.M.-T. designed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; S.A.-S. performed most of the experiments; F.I., K.A., N.H.T., and A.H. also performed experiments; H.-U.K. and M.D. performed bioinformatic analyses; C.T., G.E., and P.S. provided clinical samples; G.K., N.B., W.E.B., S.K., T.B., K.H., U.K., and H.S. provided reagents and analytical methods; A.B., Y.W., and M.M. were involved in microarray ChIPs design and array spotting; D.-Y.U. provided Prdx2 knockout mice; S.V.S. helped with manuscript editing and analysis methods; and all authors read and checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Carsten Müller-Tidow, Department of Medicine A, Hematology and Oncology, University of Muenster, Domagkstr 3, 48129 Muenster, Germany; e-mail muellerc@uni-muenster.de; and Shuchi Agrawal-Singh, Biotech Research & Innovation Centre (BRIC), Copenhagen Biocenter, Ole Maaløes Vej 5, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark; e-mail: shuchi.agrawal@bric.ku.dk or shuchiasingh@gmail.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal