Abstract

Primary testicular lymphoma (PTL) is a rare, clinically aggressive form of extranodal lymphoma. The vast majority of cases are histologically diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but rarer subtypes are clinically important and must be recognized. In this review, we discuss the incidence, clinical presentation, and prognostic factors of PTL and present a summary of the recent advances in our understanding of its pathophysiology, which may account for the characteristic clinical features. Although outcomes for patients with PTL have historically been poor, significant gains have been made with the successive addition of radiotherapy (RT), full-course anthracycline-based chemotherapy, rituximab and central nervous system–directed prophylaxis. We describe the larger retrospective series and prospective clinical trials and critically examine the role of RT. Although rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone given every 21 days with intrathecal methotrexate and locoregional RT is the current international standard of care, a substantial minority of patients progress, representing an unmet medical need. Finally, we discuss new treatment approaches and recent discoveries that may translate into improved outcomes for patients with PTL.

Introduction

Primary testicular lymphoma (PTL) is an uncommon and aggressive form of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) accounting for <5% of testicular malignancies and 1% to 2% of NHL cases.1 With a median age at diagnosis of 66 to 68 years,2-5 PTL is both the most common testicular malignancy in men age >60 years and the most common bilateral testicular neoplasm.6 Population-based studies have estimated the annual incidence at 0.09 to 0.26 per 100 000 population.1,7

Clinical features, risk factors, and etiology

Typical presentation consists of a firm, painless testicular mass without preference for either side, inseparable from the affected testis, with median tumor size at presentation of 6 cm.8 There is an associated hydrocele in ∼40% of cases.2 Synchronous bilateral involvement occurs in 6% to 10% of cases.7,9 Constitutional symptoms at diagnosis are uncommon, but if they are present, they strongly suggest systemic disease, which is present in 20% to 30% of patients.7,9 PTL has marked extranodal tropism, and relapses frequently involve sites including the central nervous system (CNS), skin, contralateral testis, and pleura.3,5,10-12 Although there are limited data regarding specific risk factors for PTL, HIV infection is a known risk factor for aggressive NHL, with lymphomas in HIV-infected patients more commonly presenting with extranodal primary sites, including the testis.13 HIV-positive patients with PTL are younger (median age, 36 years) with immunoblastic, plasmablastic, or Burkitt-like histology being more frequent, along with a median overall survival (OS) <6 months prior to use of combined antiretroviral therapy.14 Although data are scarce, it is likely that since the introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy, outcomes for HIV-positive patients with PTL have improved in line with nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).15

There are several putative mechanisms for the link between PTL and CNS relapse. This may in part reflect the biologic characteristics of tumors arising in an immune privileged site. Lymphomas arising under the selective pressure of immune surveillance may develop an immune escape phenotype.16 Common to both PTL and primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) are high levels of immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain gene somatic hypermutation17 and loss of human leukocyte antigen expression resulting from gene deletions,18,19 which may assist evasion of the host antitumor response. In addition, a nascent PTL clone may benefit from developing in an immune privileged site behind the blood-testis barrier, which has several components designed to shield developing gametocytes. These include (1) a mechanical barrier formed by the tight junction between Sertoli and endothelial cells preventing the passage of large/hydrophilic molecules,20 (2) an efflux pump (P-glycoprotein; MRP1) for smaller/lipophilic molecules, (3) an immunologic barrier formed by Sertoli cells that hinders the passage of antibodies,21 and (4) local production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.22

Menter et al23 studied 45 cases of PTL by using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization, finding low levels of p53 expression but high levels of phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), overexpression of pCXCR4, and upregulation of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway. Although few patients had clinical outcome data available, expression of both CXCR4 and pCXCR4 was predictive of inferior progression-free survival (PFS) (P = .007). Little is known about the role of CXCR4 expression in lymphoma, although the chemokine receptor has myriad biologic functions, including trafficking of lymphocytes to sites of inflammation, hematopoietic cell homing, trafficking of tumor cells to target organs, proliferation and directed migration of neuronal cells, and infiltration of activated monocytes to areas of ischemic injury.24 Preclinical models have shown that directed metastasis is mediated by CXCR4 activation and migration toward CXCR12-expressing target organs.24 Thus, overexpression of CXCR4 may predispose PTL toward extranodal relapse.

Diagnosis and staging

Imaging modalities that may assist in diagnosis include ultrasonography, which demonstrates focal or diffuse areas of hypoechogenicity with hypervascularity in an enlarged testis,25,26 and magnetic resonance imaging, which allows simultaneous evaluation of both testes, paratesticular spaces, and spermatic cord; typical findings include T2 hypointensity and strong heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement.27 When PTL is suspected, inguinal orchiectomy is required for achievement of optimal disease control and adequacy of a pathologic specimen. In view of the rarity of PTL and frequent presentation to nonhematologists, it is important that the appropriate IHC be performed (see “Pathology”) and that expert pathology review is sought for difficult cases, because distinguishing some cases from seminoma can be difficult.28

Recommended staging is the same as that for other forms of aggressive NHL (positron emission tomography-computed tomography, bone marrow biopsy) with the addition of specific CNS staging with lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis by cytology and flow cytometry (since there is evidence to support improved sensitivity29 ) and brain magnetic resonance imaging. We recommend thorough examination of the skin because cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) and testicular DLBCL have been concurrently reported,30 and the skin is a potential site of extranodal recurrence. HIV serology should be performed. As with other forms of NHL, the Ann Arbor system is used for staging, although it was not specifically designed for extranodal lymphomas. Patients with isolated bilateral involvement of the testes have a prognosis similar to that of patients with stage I/II disease31 ; therefore, we agree with existing recommendations that such cases be considered stage I.32 In the largest series, 60% to 79% of patients were stage I/II at presentation,3,7,11,33 although from a pragmatic perspective, patients with stage III/IV PTL can be considered identical to patients with systemic nodal DLBCL with secondary testicular involvement. Distinguishing between the two entities is difficult and somewhat arbitrary, because it usually cannot be determined in retrospect whether the testicular mass was truly the initial site of disease, and the prognoses for both are similar.7

Pathology

The large majority of PTLs (80% to 98%) are DLBCLs, although patients with HIV infection often present with more aggressive variants. DLBCL-type PTL typically expresses B-cell markers CD19, CD20, CD79a, and PAX5; Bcl-2 protein is expressed in 70% of cases, but Bcl-6 is rarely positive.23 The median MIB1 proliferative index is 40%, and in the non-HIV population, Epstein-Barr virus is usually negative.23 Rare histologies include mantle cell lymphoma,34-36 extranodal natural killer–cell lymphoma,37 peripheral T-cell lymphoma,38 extranodal marginal zone lymphoma,39 and activin receptor-like kinase-1–negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma.40

Pediatric follicular lymphoma of the testis

Pediatric follicular lymphoma (FL), a rare entity, deserves special mention, because it appears to have characteristics distinct from nodal FL and requires a distinct management approach. Of the 15 cases reported, typical features included grade 3A morphology, stage IE disease, expression of CD10 and Bcl-6 by IHC but lack of Bcl-2 protein expression or BCL2 gene rearrangement and indolent clinical behavior.41-45 In contrast, adults with primary FL of the testis are reported to bear the BCL2 gene rearrangement and overexpress Bcl-2 protein.41 The optimal therapy is unclear, with most patients treated with orchiectomy plus abbreviated anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. However, two patients were managed with surgery alone and remained in ongoing clinical remission at 30 and 96 months.45,46 Although data are scarce, outcomes appear favorable without reports of CNS relapses to date.

Cell-of-origin studies and chromosomal translocations

In PTL with DLBCL histology, cell of origin determined by either IHC-based algorithms47 and/or DNA microarray is activated B-cell–like (ABC) in 60% to 96% of cases.4,36,48-50 The variation in frequency is dependent on both the proportion of patients with advanced-stage disease (in which it is difficult to distinguish PTL from nodal DLBCL with testicular metastases) and the IHC algorithm used.47 The true proportion of cases that are ABC type is likely to be at the higher end of the published estimates, because even though 6% to 36% of cases are CD10+ in published series36,48,50 and are classified as germinal center B-cell–like by the Hans algorithm,47 many also express the B-cell activation marker MUM1. Some scoring systems consider such cases to be ambiguous, fitting neither the ABC nor the germinal center B-cell–like subtype.51 Booman et al48 determined cell of origin by using both IHC and gene expression profiling. By IHC, 14 (64%) were clearly ABC type (CD10–Bcl-6+/−MUM1+); however, 8 (36%) were classified as ambiguous (CD10+Bcl-6+MUM1+), and 7 (88%) of 8 of these ambiguous cases were reclassified as ABC type by gene expression analysis. This predominance of ABC type may partially account for the historically poor outcomes from PTL.52 Recent data in nodal DLBCL suggest that the adverse outcome conferred by the ABC subtype may be attributable to chronic active B-cell receptor signaling and constitutive NF-κB and PI3K activation.53 Interestingly, a large international consortium found that coexpression of MYC and Bcl-2 protein contributed to the inferior survival of ABC-type nodal DLBCL.54 However, the limited data available suggest that the frequency of either a proteomic or a cytogenetic double hit with MYC and Bcl-2 in PTL is low. Bernasconi et al55 performed cytogenetic analyses by using split-signal fluorescence in situ hybridization probes in 16 patients with PTL, finding 3 cases (19%) bearing MYC translocations. Menter et al23 found that only 5 (13%) of 38 PTL cases expressed c-myc protein, but all 5 also expressed Bcl-2 protein. Finally, the dependence of ABC-type DLBCL on MYD88, an adaptor protein which acts through Toll-like receptor and interleukin-1 receptor, was recently described.56 Kraan et al57 found mutations in MYD88 in >70% of PTL and PCNSL but in <20% of patients with nodal DLBCL, providing further evidence for differences in pathophysiology.

Prognostic factors and patterns of relapse

Numerous prognostic factors for PTL have been described, largely derived from small retrospective series, often including patients who had disseminated disease with testicular involvement. Thus, although the International Prognostic Index (IPI) and its components have been frequently reported as prognostic factors, they are surrogate markers of high tumor burden and disseminated disease. For the majority of patients with PTL who present with limited-stage disease, the IPI is typically <2 and therefore has limited prognostic utility.58 The adverse prognostic markers for PFS are summarized in Table 1; those for OS are similar with one study also identifying infiltration of adjacent tissues.59 The impact of non-DLBCL histology is difficult to determine because of the rarity of such cases. A Dutch series found evidence that transformed extranodal marginal zone lymphoma was associated with smaller tumor size, less frequently elevated lactate dehydrogenase, absence of B symptoms, more frequent stage IE disease, lower IPI than pure DLBCL, and a nonsignificant trend toward improved survival.39

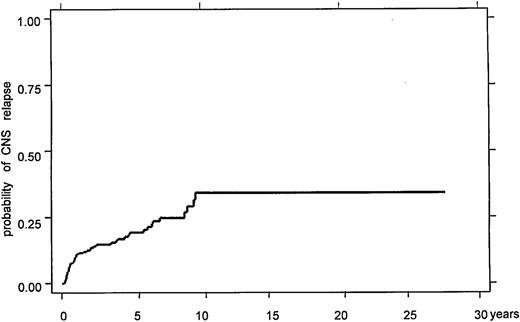

A particular characteristic of PTL is the temporal pattern of continuing relapses, even >15 years after initial treatment, which frequently involves sanctuary sites such as the contralateral testis and CNS.3 Relapses often occur at multiple extranodal sites, including lung, soft tissue, adrenal glands, liver, and bone marrow.3,5,11,12 The crude incidence of CNS involvement in PTL has been reported in smaller series as up to 44%, although estimates vary widely and use of CNS-directed prophylaxis was typically nonuniform.3,5,12,33,60 The best estimate of risk in the prerituximab era is from the large, retrospective International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) series of 381 patients with PTL.11 The 5- and 10-year actuarial risks of 19% and 34% are substantially greater than those for nodal DLBCL (Figure 1).61 As is the case in nodal DLBCL,62 CNS parenchymal relapse is more frequent than leptomeningeal relapse; in the IELSG series, 64% of CNS relapses involved brain parenchyma, and 61% were isolated to the CNS, consistent with other series.11

Treatment and outcomes

Systemic therapy (chemotherapy and rituximab)

Historically the outcome of PTL has been inferior to that of nodal DLBCL with no plateau in PFS and OS curves in retrospective studies (Table 2).4,5,9,11,12,33,63 As previously outlined, orchiectomy alone is indicated for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. However, outcomes of patients treated with orchiectomy and/or radiation alone are poor.7,64 Many chemotherapy strategies have been used, but the rarity of the tumor has prevented the conduct of prospective randomized comparisons among chemotherapy strategies. Thus, the available data are drawn from either nonrandomized phase 2 studies or from retrospective series.

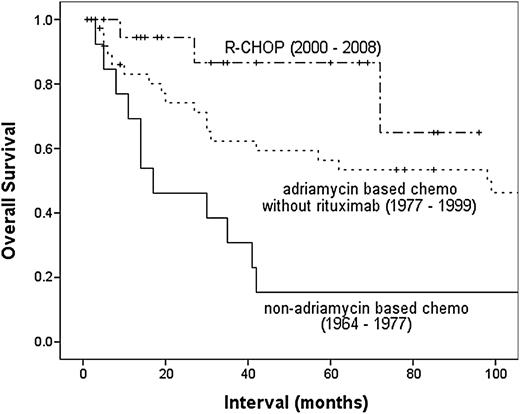

The outcome of patients with PTL has been gradually improving. A retrospective MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) series showed incremental improvements in PFS and OS over time with refinement of treatment strategy (Figure 2).12 This trend is mirrored by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry in which analysis by treatment era (defined by 5-year intervals) showed incremental improvements in OS, with a median OS of 1.8 years for patients diagnosed in 1980-1985 but median not yet reached for those diagnosed 20 years later (5-year disease-specific survival, 62.4%).7 On the basis of nodal DLBCL, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) at 21-day intervals was the most widely used regimen for PTL prior to the introduction of rituximab, achieving 5-year OS of 30% to 52%.12,65 Attempts to improve on this with the addition of bleomycin,10,66 increasing dose-density,10 or use of more intensive strategies such as hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone given as course A, followed by methotrexate and cytarabine given as course B) 63 have been limited to small retrospective series that did not demonstrate any appreciable improvements. In addition, the deliverability of such dose-intensive strategies is limited, given the demographic features of the majority of patients with PTL.

Time to CNS recurrence in the IELSG retrospective study, demonstrating ongoing risk of late CNS relapses. Reprinted from Zucca et al11 with permission.

Time to CNS recurrence in the IELSG retrospective study, demonstrating ongoing risk of late CNS relapses. Reprinted from Zucca et al11 with permission.

The impact of rituximab on outcomes in PTL remains unclear, but appears less definitive than in nodal DLBCL. A retrospective analysis from the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) of 88 patients with PTL treated with CHOP either with (n = 48) or without (n = 40) rituximab found (after a median follow up of 60 months) that there was no difference in 5-year rates of progression or OS.67 However, the rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP) group contained more patients with adverse prognostic factors, and multivariate analysis found that the use of rituximab was a favorable prognostic factor for both time to progression (P = .006) and OS (P = .009). Rituximab had no evident impact on CNS relapse in this study. The improvement in outcome was also noted in the MDACC retrospective series, in which the addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy resulted in significant improvements in 5-year OS (56% vs 87%; P = .019) despite no such improvement in PFS (52% vs 59%; P = .138), suggesting that improved salvage therapies may have been responsible.12

CNS prophylaxis

The apparent lack of impact of rituximab on CNS relapse risk in the BCCA series is not surprising, given that levels of rituximab in cerebrospinal fluid are only 0.1% that of serum levels,68 and a recent meta-analysis suggested only minor reduction in CNS relapse in nodal DLBCL.61 In an attempt to ameliorate the high risk of CNS relapse, intrathecal chemotherapy has been used in many retrospective series.3-5,12 However, given the nonuniform application inherent in retrospective case series, drawing firm conclusions about the efficacy of intrathecal methotrexate is difficult. Of the prospective clinical trials performed, two used intrathecal chemotherapy alone and reported CNS relapse rates of 6%,58,69 while one used both intrathecal and systemic methotrexate and reported no CNS relapses among 38 patients.70 In all 3 studies, the crude incidence of CNS relapse was significantly less than that for historical controls. Given that many relapses are parenchymal rather than leptomeningeal and that the penetration into brain parenchyma and distribution around the neuroaxis of methotrexate injected by lumbar puncture is limited,71 there is a conceptual appeal to the use of high-dose systemic methotrexate for CNS prophylaxis because it achieves higher drug levels in brain parenchyma.72 Furthermore, in nodal DLBCL, the addition of high-dose systemic methotrexate appears to lower the risk of CNS relapse.73-75 The merits of this approach are reflected by treatment guidelines,76 and the ongoing IELSG-30 prospective protocol incorporates intravenous methotrexate (1.5 g/m2) in addition to intrathecal liposomal cytarabine (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00945724). Dose reductions should be made for patients with renal impairment and for the elderly.

Prospective clinical trials in PTL

Few prospective clinical trials in PTL have been conducted (Table 3). The Groupe Ouest Est d'Etude des Leucémies et Autres Maladies du Sang (GOELAMS) 02 study used 3 cycles of VCAP in patients age 18 to 60 years, or VCEP-bleo (vindesine, cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, prednisolone, and bleomycin) in patients age 61 to 75 years. All patients received radiotherapy (RT) to inguinal, iliac, and para-aortic lymph nodes, whole brain RT, and intrathecal prophylaxis.69 With a median follow-up of 73.5 months, DFS and OS were 70% and 65%, respectively, with one CNS relapse (6%).

Avilés et al70 conducted a single-arm, open-label study using 6 cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide (1500 mg/m2), epirubicin (120 mg/m2), vincristine, prednisolone (R-CEOP) dosed at 14-day intervals, with patients who achieved complete response (CR) receiving 30 Gy RT to the scrotum and contralateral testis. CNS prophylaxis comprised 4 cycles of high-dose intravenous methotrexate (6 g/m2) with leucovorin rescue. Of the 38 patients enrolled, 86% achieved CR, and the actuarial 5-year event-free survival and OS were 70% and 66%, respectively. No CNS relapses were reported in this study.

The IELSG-10 study was a multicenter phase 2 study that evaluated R-CHOP delivered at 21-day intervals followed by locoregional irradiation.58 Intrathecal methotrexate was used for CNS prophylaxis during the first 2 chemotherapy cycles. Fifty-three patients with stage I/II DLBCL-type PTL were included (patients with bilateral testicular involvement were considered stage I); 98% achieved CR and, after median follow up of 65 months, the 5-year PFS and OS were 74% and 85%, respectively. The 5-year actuarial incidence of CNS relapse was 6%. The excellent results in this study established R-CHOP every 21 days with intrathecal methotrexate and locoregional RT as the reference treatment for patients with limited-stage PTL, including those with bilateral testicular involvement. Thus, we regard R-CHOP every 21 days with intrathecal methotrexate with scrotal RT after completion of chemotherapy as the recommended treatment of these patients also.

There are limited data regarding the use of abbreviated chemotherapy in PTL. An early report from BCCA treated 15 patients with stage I/II PTL with either 3 cycles of CHOP or a 6-week regimen modified from MACOP-B (methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin), termed ACOB (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, bleomycin, and prednisolone).66 They reported a remarkable 4-year PFS and OS of 93%, with no CNS relapses. This result should be considered in the context of the small number of patients and it has not been replicated. Conversely, there are data suggesting that abbreviated chemotherapy compromises outcomes. Seymour et al,5 in a retrospective series of 25 patients, reported a shorter median time to treatment failure (1.2 vs 8.4 years; P = .03) in patients who received <6 cycles of chemotherapy. Supporting this, patients in the IELSG retrospective series who received ≥6 cycles of chemotherapy had a better long-term outcome than those treated for a shorter period (10-year OS, 44% vs 19%; P = .03).11

RT

Early studies of PTL included patients treated with orchiectomy and locoregional RT only and were associated with uniformly high rates of relapse.2 The use of RT alone for PTL would be considered only for patients who refused or were unfit for systemic chemotherapy.2 Recent efforts to improve the management of PTL have focused on prophylactic therapy for sanctuary sites, such as the CNS and contralateral testis.58

Testicular irradiation.

Patients treated by orchiectomy and anthracycline-based chemotherapy have an appreciable risk of relapse in the contralateral testis.1,3,9 In the IELSG series, testicular relapse was a component of 43 (45%) of 195 treatment failures, with 15-year actuarial incidence of contralateral testicular relapse of 42% in the absence of scrotal irradiation.11 Prophylactic scrotal radiation was associated with significant reduction in the incidence of testicular relapse (P = .011) and improvement in both 5-year PFS (70% vs 36%; P = .00001) and OS (66% vs 38%; P = .00001).11 Other studies have also suggested that the addition of adjuvant RT improves survival, although it is uncertain to what extent this reflects patient selection for adjuvant irradiation.7,77

In the IELSG-10 study, adjuvant testicular radiation (median, 30 Gy; range, 24 to 40 Gy) was used routinely with no testicular relapses observed.58 RT should thus be considered mandatory in stage I to II disease. Adjuvant scrotal radiation may have more value in limited-stage disease, because in the IELSG series, testicular relapse occurred in 28% of treatment failures for stage I and was the sole initial site of failure in 10%, whereas for patients with initial stage III to IV disease, testicular relapse occurred in 16% of failures but was the sole site of failure in only 2%. Nonetheless, given the relatively low morbidity of this treatment, it should be considered standard care for all patients who are receiving potentially curative chemotherapy. Despite this, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data showed that only 30% to 40% of patients received RT, without apparent improvement over time.7

Nodal irradiation.

In stage I PTL, there is no role for adjuvant irradiation to uninvolved para-aortic or pelvic nodes. In stage II PTL, the benefit of RT to involved nodes in patients treated with R-CHOP is uncertain. For example, in the IELSG-10 study of 13 stage II patients, 9 received nodal RT, and the single relapse occurred within the RT field in one of these patients.58 The 4 patients not treated with RT were all in remission at the time of reporting; however, the small number of patients and nonrandomized allocation of RT means that this question remains open. There are limited data to suggest benefit of regional nodal irradiation in stage III/IV disease; thus, it is not recommended.

Toxicity.

Testicular irradiation causes acute cutaneous toxicity, which may last several weeks. The major long-term toxicities of scrotal irradiation are dose-dependent and include infertility and hypogonadism.78 The acute toxicities of abdominal and pelvic irradiation include lethargy, nausea, disturbance of bowel function, and cytopenias, while late toxicity primary consists of increased risk of second primary malignancies.

Management of relapsed disease

The prognosis of patients with PTL who experience relapse is poor. The median survival after relapse is infrequently reported but was <2 months in the Danish series.1 The narrow gap between reported PFS and OS in most other studies suggests that this estimate is probably accurate. The likely explanations for this dismal outlook are the high frequency of CNS relapse and the average patient is elderly and has comorbidities precluding aggressive salvage strategies and/or stem cell transplantation.

It is difficult to make robust evidence-based recommendations for the optimal approach for patients with relapsed PTL. Four (22%) of 18 patients with relapsed lymphoma in the MDACC series underwent autologous stem cell transplantation, but their outcomes were not reported.12 Interestingly, of the 9 patients with relapsed lymphoma in the IELSG-10 study, 4 (44%) remained alive in second remission after unspecified salvage therapy,58 perhaps suggesting that prevention of CNS relapse may result in greater potential to salvage patients in the future.

Future Directions

New insights into the distinctive pathophysiology of PTL may facilitate novel therapeutic strategies. There is evidence that both lenalidomide79 and the inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase ibrutinib80 are active in ABC-type DLBCL. Several groups are exploring R-CHOP in combination with lenalidomide (R2-CHOP)81-84 and ibrutinib in nodal DLBCL. The data available so far suggest that these combinations are well tolerated and effective, although to the best of our knowledge, patients with PTL are not specifically being studied. The presence of lenalidomide has been demonstrated in the semen of male patients,85 and a case of multiple myeloma invading the testis was successfully treated using lenalidomide and dexamethasone, suggesting penetration of the blood-testis barrier.86 Data regarding the CNS penetration of lenalidomide are lacking; however, 2 phase 1 studies in patients with refractory CNS tumors have demonstrated low toxicity but poor response rates.87,88 Pomalidomide, another immunomodulatory drug has demonstrated both synergistic enhancement of antigen-dependent cellular cytotoxicity with rituximab89 and excellent CNS penetration and impressive activity against a Raji xenograft model of PCNSL.90 Thus, given the promising activity of R2-CHOP, combining pomalidomide with rituximab and/or chemotherapy in patients with PTL may have appeal.

If CXCR4 is found to have a pathophysiologic role in mediating extranodal relapse, development of the CXCR4 inhibitor plerixafor (currently licensed for peripheral blood stem cell mobilization) may prove attractive as a therapeutic adjuvant to chemotherapy. Finally, the overactivation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways may be exploited as a target; a small-molecule inhibitor of JAK-STAT signaling has shown in vitro activity against ABC-type DLBCL cell lines and is synergistic with NF-κB pathway inhibitors.91 Further improvements in the outcome of patients with PTL are likely to be achieved only by collaborative enrollment of patients into thoughtfully designed, prospective clinical trials.

In conclusion, significant gains have been made in PTL with the successive addition of RT, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, rituximab, and CNS-directed prophylaxis. Although R-CHOP every 21 days with intrathecal methotrexate and locoregional RT is the current international standard of care, there is unmet medical need for patients for whom this approach fails. A greater understanding of the pathophysiologic processes underlying the characteristic tropism of PTL has the potential for further improvements in treatment of this rare but aggressive disease.

OS of patients with PTL treated at MDACC, by chemotherapy strategy. Adriamycin (doxorubicin). Reprinted from Mazloom et al12 with permission.

OS of patients with PTL treated at MDACC, by chemotherapy strategy. Adriamycin (doxorubicin). Reprinted from Mazloom et al12 with permission.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jan Delabie for his critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Victorian Cancer Agency (grant number CTCB11_18) and the Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand (New Investigator Scholarship).

Authorship

Contribution: C.Y.C., A.W., and J.F.S. performed the literature review and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John F. Seymour, Department of Haematology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Locked Bag 1, A’Beckett St, East Melbourne 8006, VIC, Australia; e-mail: john.seymour@petermac.org.