Key Points

Expression of ITGA2B (CD41) and MPL positively correlates with that of EVI1 in acute myeloid leukemia patients.

Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling enhances growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells with a high leukemia-initiating capacity.

Abstract

Ecotropic viral integration site 1 (Evi1) is a transcription factor that is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells and is crucial for their self-renewal capacity. Aberrant expression of Evi1 is observed in 5% to 10% of de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients and predicts poor prognosis, reflecting multiple leukemogenic properties of Evi1. Here, we show that thrombopoietin (THPO) signaling is implicated in growth and survival of Evi1-expressing cells using a mouse model of Evi1 leukemia. We first identified that the expression of megakaryocytic surface molecules such as ITGA2B (CD41) and the THPO receptor, MPL, positively correlates with EVI1 expression in AML patients. In agreement with this finding, a subpopulation of bone marrow and spleen cells derived from Evi1 leukemia mice expressed both CD41 and Mpl. CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells induced secondary leukemia more efficiently than CD41− cells in a serial bone marrow transplantation assay. Importantly, the CD41+ cells predominantly expressing Mpl effectively proliferated and survived on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of THPO via upregulating BCL-xL expression, suggesting an essential role of the THPO/MPL/BCL-xL cascade in enhancing the progression of Evi1 leukemia. These observations provide a novel aspect of the diverse functions of Evi1 in leukemogenesis.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal hematologic disorder in which somatically acquired genetic alterations in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells disturb their growth and differentiation. Chromosomal abnormalities or specific gene mutations are used in the risk classification of AML as prognostic biomarkers. In addition, distinct gene expression signatures have been used to identify the prognostic subclasses of AML.1 Among these stratified groups, aberrant expression of ecotropic viral integration site 1 (Evi1) occurs in approximately 5% to 10% of de novo AML patients and defines one of the largest clusters in AML.2-5 EVI1 gene is located on chromosome 3q26, and its inappropriate expression is often caused by 3q abnormalities such as inv(3)(q21q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21;q26.2).6 According to the World Health Organization classification, AML with inv(3)(q21q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21;q26.2) is associated with normal or elevated platelet counts and shows increased atypical bone marrow (BM) megakaryocytes and associated multilineage dysplasia.7 Furthermore, monosomy 7 and 11q23 translocations involving the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene are frequently accompanied by deregulated expression of Evi1.2,4,5 Regardless of cytogenetics, high Evi1 expression predicts adverse outcome mainly due to a poor therapeutic response.8

Evi1 is a transcription factor highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and is crucial for their self-renewal capacity.9 Meanwhile, Evi1 exerts diverse oncogenic functions by suppressing transforming growth factor-β signaling,10 inhibiting c-Jun N-terminal kinase,11 inducing activator protein-1 activity,12 and activating AKT/mTOR signaling through PTEN repression.13 Moreover, Evi1 physically interacts with multiple components of epigenetic machineries,14-18 demonstrating a wide variety of roles in gene regulation. Several surface molecules, such as CD52 and integrin α 6,19,20 specifically expressed in Evi1 leukemia cells have also been identified.

In this study, we sought to clarify specific molecular features of AML with high Evi1 expression using the mouse model of Evi1 leukemia that we previously established.13,21 By analyzing gene expression data of AML patients, we first revealed that the expression of ITGA2B (CD41), a megakaryocytic differentiation marker, positively correlates with that of EVI1. In Evi1 leukemia mice, a subpopulation of leukemia cells did express CD41. Importantly, CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells had a more efficient leukemia-initiating capacity (LIC) than CD41− cells. In addition, Mpl, the receptor for thrombopoietin (THPO), was predominantly expressed in the CD41+ cells, and stimulation by THPO supported their growth and survival via upregulation of BCL-xL. These results suggest that the THPO/MPL pathway can be critical for the progression of Evi1 leukemia as a cell-extrinsic factor.

Methods

Vectors

Retroviral vectors used for transformation of primary murine BM cells were pMYs-mouse Evi1-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-green fluorescent protein (GFP)13 and pMSCV-MLL-ENL-IRES-GFP.22 The pMYs-mouse Evi1-IRES-GFP vector was also used for generating Evi1 leukemia mice. Murine Evi1 gene used in this study encodes the Evi1 isoform of Mds1 and Evi1 complex locus (Mecom), and its sequence information has been registered with the accession number JQ665270.1 in GenBank.

Generation of Evi1 leukemia mice

Evi1 leukemia mice were generated as described previously.13,21 In brief, BM mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) isolated from C57BL/6 mice after treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) were retrovirally transduced with Evi1. The infected cells were injected through the tail vein into sublethally irradiated (5.25 Gy) syngeneic recipient mice. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Tokyo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry

Cell sorting and analysis were performed by using FACSAriaII, FACSAriaIII, and LSRII (all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The data were analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The anti-mouse Mpl monoclonal antibody (clone AMM2; provided by Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Tokyo, Japan) was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 using the Alexa Fluor 647 Monoclonal Antibody Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. See the supplemental Methods (available at the Blood Web site) for more information.

In vitro culture of Evi1 leukemia cells

For cell proliferation and apoptosis assays, CD41+ and CD41− Evi1 leukemia cells (each 5 × 104 per well) were seeded onto a confluent layer of OP9 stromal cells in a 24-well plate in the presence of stem cell factor (SCF) (50 ng/mL) and/or THPO (50 ng/mL). Chemical inhibitors used were AG490 (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), PD98059 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), Ly294002 (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA), and WEHI-539-hydrochloride (ChemScene, Monmouth Junction, NJ). See the supplemental Methods for more information.

Microarray data analysis

Three sets of microarray data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo): expression data of 461 human AML cases (GSE6891)23 and another cohort of 422 AML cases (GSE37642)24 and expression data of murine c-kit+/Sca-1+/lineage− cells (referred to as KSL) derived from Evi1 wild-type and conditional knockout (cKO) mice (GSE11557).9 See the supplemental Methods for more information.

Statistics

The data were analyzed by Student t test, Tukey’s test, or Dunnett’s test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < .05. To analyze the survival curve, the log-rank test was used. LIC frequency was calculated by Poisson statistics. Data analysis was performed using R software (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

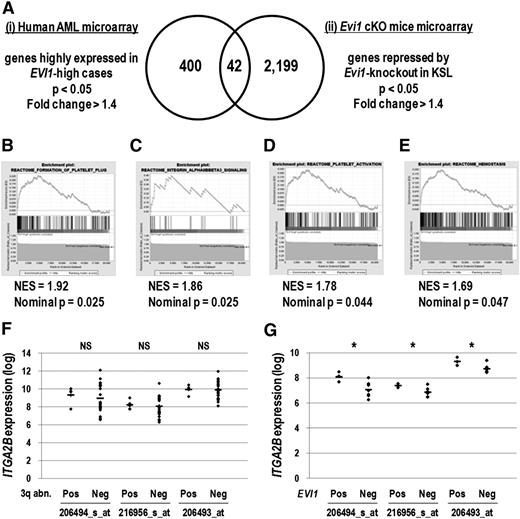

Expression of ITGA2B correlates with that of EVI1 in human AML

To identify cell-surface molecules specific to Evi1-overexpresssing leukemia cells, we analyzed 2 sets of microarray data. First, gene expression profiles consisting of 460 human AML samples23 were divided into EVI1-high (30 cases) and EVI1-low (430 cases) groups, and 400 genes highly expressed in the EVI1-high group were extracted (supplemental Table 1). To narrow down the candidate genes, we selected 2199 genes repressed by Evi1 deletion using the gene expression profiles of KSL derived from Evi1 wild-type and cKO mice (supplemental Table 2).9 We then identified 11 cell-surface molecules among 42 genes commonly found in these lists (Figure 1A, Table 1, and supplemental Table 3). These candidate genes contained several megakaryocyte/platelet lineage markers such as ITGA2B (CD41), ITGB3 (CD61), PEAR1, SELP, and MPL. Analysis of another set of AML microarray data24 confirmed that the expression of ITGA2B, MPL, and SELP was correlated with that of EVI1 (supplemental Table 4). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis revealed that molecular signatures relevant to platelet function and integrin αIIbβ3 (CD41/CD61) signaling were significantly enriched in the EVI1-high group (Figure 1B-E). These results indicate that the expression of megakaryocytic markers, in particular ITGA2B, strongly correlates with that of EVI1 in human AML.

Genes expressed in the megakaryocyte and platelet lineage correlate with EVI1 expression. (A) The candidate genes positively correlated with EVI1 expression were extracted by analyzing 2 different sets of microarray data: (i) human AML BM specimens (GSE6891) and (ii) KSL cells derived from Evi1 cKO mice (GSE11557). For human AML microarray analysis, samples were divided into EVI1-high AML (30 cases) and EVI1-low AML (430 cases) groups according to EVI1 expression as well as diagnostic information, and then 400 genes highly expressed in the EVI1-high AML group were identified (fold change > 1.4 and P < .05). From Evi1 cKO mice microarray data, 2199 genes downregulated by Evi1-knockout in KSL cells were extracted (fold change > 1.4 and P < .05). The Venn diagram revealed that 42 genes were highly correlated with EVI1 expression. (B-E) According to the gene set enrichment analysis, several gene sets related to platelet function were enriched in the EVI1-high AML group compared with the EVI1-low AML group. (B) Gene set name: REACTOME_FORMATION_OF_PLATELET_PLUG; 174 genes. (C) Gene set name: REACTOME_INTEGRIN_ALPHAIIBBETA3_SIGNALING; 23 genes. (D) Gene set name: REACTOME_PLATELET_ACTIVATION; 155 genes. (E) Gene set name: REACTOME_HEMOSTASIS; 262 genes. NES indicates the normalized enrichment score. (F) Comparison of ITGA2B expression levels between EVI1-high cases with 3q abnormalities (n = 5) and those without 3q abnormalities (n = 25) (GSE6891). The expression levels of ITGA2B were comparable irrespective of the presence of 3q abnormalities (NS, not significant; Student t test). Three probe IDs examined are described in Table 1. (G) Comparison of ITGA2B expression levels between EVI1-positive MLL-rearranged cases (n = 3) and EVI1-negative MLL-rearranged cases (n = 7) (GSE6891). ITGA2B expression levels in EVI1-positive MLL-rearranged cases were higher than those in EVI1-negative MLL-rearranged cases (*P < .05, Student t test).

Genes expressed in the megakaryocyte and platelet lineage correlate with EVI1 expression. (A) The candidate genes positively correlated with EVI1 expression were extracted by analyzing 2 different sets of microarray data: (i) human AML BM specimens (GSE6891) and (ii) KSL cells derived from Evi1 cKO mice (GSE11557). For human AML microarray analysis, samples were divided into EVI1-high AML (30 cases) and EVI1-low AML (430 cases) groups according to EVI1 expression as well as diagnostic information, and then 400 genes highly expressed in the EVI1-high AML group were identified (fold change > 1.4 and P < .05). From Evi1 cKO mice microarray data, 2199 genes downregulated by Evi1-knockout in KSL cells were extracted (fold change > 1.4 and P < .05). The Venn diagram revealed that 42 genes were highly correlated with EVI1 expression. (B-E) According to the gene set enrichment analysis, several gene sets related to platelet function were enriched in the EVI1-high AML group compared with the EVI1-low AML group. (B) Gene set name: REACTOME_FORMATION_OF_PLATELET_PLUG; 174 genes. (C) Gene set name: REACTOME_INTEGRIN_ALPHAIIBBETA3_SIGNALING; 23 genes. (D) Gene set name: REACTOME_PLATELET_ACTIVATION; 155 genes. (E) Gene set name: REACTOME_HEMOSTASIS; 262 genes. NES indicates the normalized enrichment score. (F) Comparison of ITGA2B expression levels between EVI1-high cases with 3q abnormalities (n = 5) and those without 3q abnormalities (n = 25) (GSE6891). The expression levels of ITGA2B were comparable irrespective of the presence of 3q abnormalities (NS, not significant; Student t test). Three probe IDs examined are described in Table 1. (G) Comparison of ITGA2B expression levels between EVI1-positive MLL-rearranged cases (n = 3) and EVI1-negative MLL-rearranged cases (n = 7) (GSE6891). ITGA2B expression levels in EVI1-positive MLL-rearranged cases were higher than those in EVI1-negative MLL-rearranged cases (*P < .05, Student t test).

Expression levels of candidate megakaryocytic marker genes were comparable between EVI1-high cases with 3q abnormalities and those without 3q abnormalities (Figure 1F and supplemental Figure 1A). When compared with MLL-rearranged cases without EVI1 expression, those with EVI1 overexpression showed higher expression of ITGA2B, MPL, and PEAR1 (Figure 1G and supplemental Figure 1B). These results suggested that expression of megakaryocytic marker genes would mark EVI1-positive AML cases irrespective of cytogenetic abnormalities.

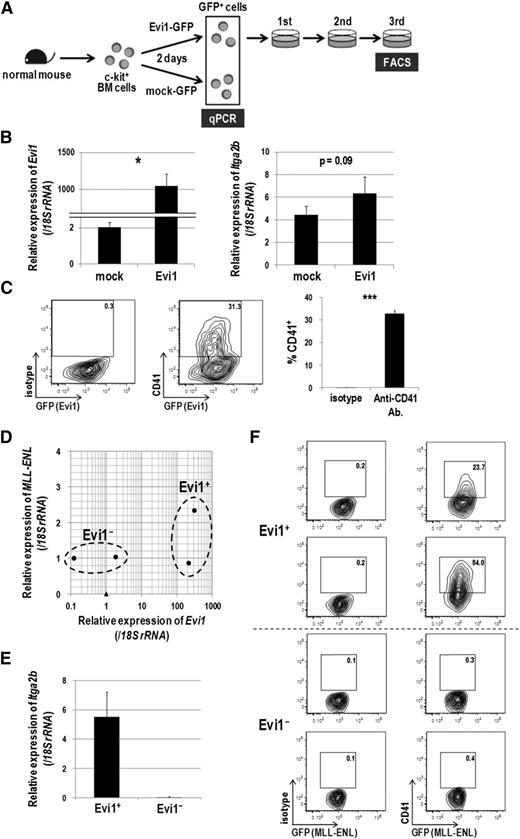

Evi1-overexpressing cells express CD41

To confirm the association between CD41 and Evi1, we next examined CD41 expression in hematopoietic cells immortalized by Evi1. Murine c-kit+ BM cells were transduced with Evi1-GFP or mock-GFP retroviral vectors, and GFP+ cells were sorted and subjected to quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (Figure 2A). Itga2b expression was increased 1.5-fold by Evi1 overexpression 2 days after transduction (Figure 2B). After 3 rounds of replating in semisolid culture, transformed Evi1-GFP+ cells clearly expressed CD41 (Figure 2C). To exclude the possibility that immortalized CD41+ cells are generated exclusively from the CD41+ normal BM cells transduced with Evi1, CD41− BM cells were purified and transduced with Evi1 (supplemental Figure 2A). Even in this setting, Evi1 overexpression induced CD41+ immortalized cells (supplemental Figure 2B). We next examined CD41 expression in MLL-ENL-transduced murine BM cells in which Evi1 expression can be upregulated.22 BM cells from 5-FU–treated mice were transduced with MLL-ENL and immortalized in semisolid culture. In this way, we obtained 2 Evi1-positive and 2 Evi1-negative clones, among which the expression of MLL-ENL transgene was not so different (Figure 2D). Although the upregulation of Evi1 was relatively mild compared with the forced expression, the Evi1+ clones clearly showed higher expression of Itga2b than the Evi1− clones and expressed CD41 (Figure 2E-F). These results demonstrated that CD41 expression is accompanied by Evi1 expression in mouse BM cells immortalized in vitro.

Evi1-overexpressing cells express CD41. (A) Schematic representation of gene expression and FACS analysis. Murine c-kit+ BM cells were transduced with Evi1-GFP or mock-GFP for 2 days, and GFP+ cells were sorted and subjected to gene expression analysis. Evi1-GFP-transduced cells were seeded in cytokine-supplemented methylcellulose culture medium (MethoCult GF M3434 from StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and serially replated. FACS analysis was performed at the third replating. Three independent experiments were performed. (B) The messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Evi1 (left) and Itga2b (right) was compared between Evi1-GFP- and mock-GFP-transduced murine BM cells. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD; n = 3; *P < .05, Student t test). (C) Surface CD41 expression was analyzed by FACS. Cells were stained with a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated isotype control antibody or a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody. Representative FACS data and a bar graph showing frequencies of CD41+ cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; ***P < .001, Student t test). (D-F) Expression analysis of CD41 in MLL-ENL-immortalized murine BM cells. (D) BM-MNCs isolated from 5-FU–treated mice were retrovirally transduced with MLL-ENL and immortalized by serially replating in semisolid culture. Four MLL-ENL-immortalized clones from 2 independent experiments were established. The mRNA expression levels of Evi1 (x-axis) and MLL-ENL (y-axis) are shown. Obviously, four MLL-ENL-transduced clones (closed circles) are divided into Evi1+ (n = 2) and Evi1− (n = 2) clones as indicated. A closed triangle indicates normal c-kit+ BM cells. (E) Comparison of Itga2b expression levels between Evi1+ and Evi1− clones. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD. (F) Surface CD41 expression was analyzed by FACS. Evi1+ clones, but not Evi1− clones, clearly expressed CD41.

Evi1-overexpressing cells express CD41. (A) Schematic representation of gene expression and FACS analysis. Murine c-kit+ BM cells were transduced with Evi1-GFP or mock-GFP for 2 days, and GFP+ cells were sorted and subjected to gene expression analysis. Evi1-GFP-transduced cells were seeded in cytokine-supplemented methylcellulose culture medium (MethoCult GF M3434 from StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and serially replated. FACS analysis was performed at the third replating. Three independent experiments were performed. (B) The messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Evi1 (left) and Itga2b (right) was compared between Evi1-GFP- and mock-GFP-transduced murine BM cells. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD; n = 3; *P < .05, Student t test). (C) Surface CD41 expression was analyzed by FACS. Cells were stained with a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated isotype control antibody or a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody. Representative FACS data and a bar graph showing frequencies of CD41+ cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; ***P < .001, Student t test). (D-F) Expression analysis of CD41 in MLL-ENL-immortalized murine BM cells. (D) BM-MNCs isolated from 5-FU–treated mice were retrovirally transduced with MLL-ENL and immortalized by serially replating in semisolid culture. Four MLL-ENL-immortalized clones from 2 independent experiments were established. The mRNA expression levels of Evi1 (x-axis) and MLL-ENL (y-axis) are shown. Obviously, four MLL-ENL-transduced clones (closed circles) are divided into Evi1+ (n = 2) and Evi1− (n = 2) clones as indicated. A closed triangle indicates normal c-kit+ BM cells. (E) Comparison of Itga2b expression levels between Evi1+ and Evi1− clones. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD. (F) Surface CD41 expression was analyzed by FACS. Evi1+ clones, but not Evi1− clones, clearly expressed CD41.

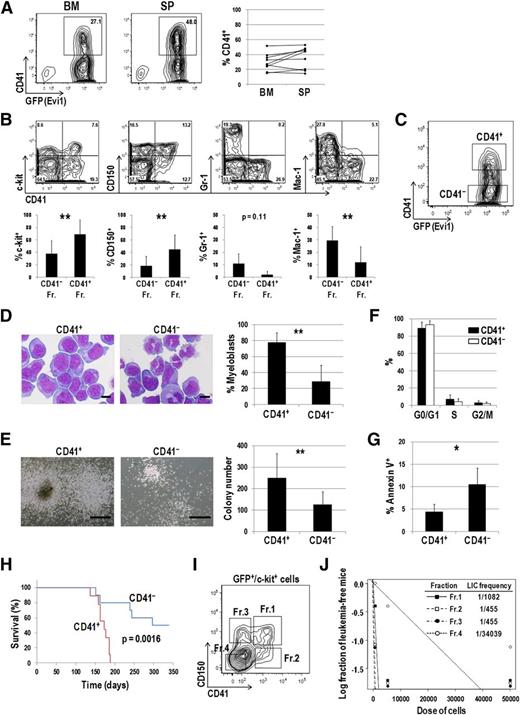

CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells have a higher LIC than CD41− cells

Next, we checked CD41 expression in the mouse model of Evi1 leukemia.13,21 As shown in Figure 3A, CD41 was distinctly expressed in BM and spleen (SP) cells of Evi1 leukemia mice. CD41+ cells expressed immature markers such as c-kit and CD150 more frequently than CD41− cells (Figure 3B). In contrast, Gr-1– and Mac-1–positive mature cells were frequently present in the CD41− fraction. We then postulated that CD41+ cells mark a phenotypically and functionally immature fraction of Evi1 leukemia mice and contain subfraction(s) with a higher LIC. Both CD41+ and CD41− cells within a GFP+, namely, Evi1+ fraction were sorted and subjected to further analysis (Figure 3C). Morphological analysis revealed that CD41+ cells contained myeloblasts with high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio more abundantly than CD41− cells (Figure 3D). In a colony-forming assay, CD41+ cells generated larger colonies and showed higher colony-forming capacity than CD41− cells (Figure 3E). There was no significant difference in cell-cycle status between CD41+ and CD41− cells (Figure 3F). On the other hand, apoptotic rates were significantly lower in CD41+ cells than in CD41− cells (Figure 3G). When transplanted into sublethally irradiated mice, CD41+ cells more rapidly induced AML than CD41− cells (Figure 3H). Expression profiles of CD41 in secondary leukemia mice were similar to those in primary leukemia mice (data not shown). Given that the significant difference of homing capacity between CD41+ and CD41− cells was not observed 12 hours after transplantation, delayed onset of AML in mice transplanted with CD41− cells might not due to its impaired homing capacity (supplemental Figure 3). To further define subpopulation(s) with a high LIC, 4 subfractions were classified based on CD41 and CD150 expression patterns within GFP+/c-kit+ cells and transplanted into mice (Figure 3I). A limiting dilution transplantation assay revealed that 3 fractions other than the c-kit+/CD41−/CD150− fraction (Fr.4) showed extremely high LIC frequencies (Figure 3J). These results demonstrated that c-kit+/CD41−/CD150+ (Fr.3) as well as c-kit+/CD41+ (Fr.1 and Fr.2) cells marked a LIC within Evi1 leukemia cells.

CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells have a higher LIC than CD41− cells. (A) The surface expression of CD41 on Evi1 leukemia cells. BM- and SP-MNCs were harvested from Evi1 leukemia mice and stained with an allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody. Representative FACS data are shown. The graph shows frequencies of CD41+ cells in BM and SP derived from 9 individual leukemia mice. (B) Surface-marker profiles of Evi1 leukemia BM cells. Cells were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody and APC-conjugated antibodies (c-kit, CD150, Gr-1, or Mac-1). Data for GFP+ cells are shown. Bar graphs show frequencies of c-kit+, CD150+, Gr-1+, and Mac-1+ cells in CD41+ and CD41− fractions. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (C) CD41+ and CD41− Evi1 leukemia cells within a GFP+ fraction were sorted and subjected to further analysis. A representative FACS plot is shown. (D) The morphologic feature of CD41+ and CD41− cells was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining, and the proportion of myeloblasts with a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio was compared between these fractions. Pictures were captured by a BH-2 microscope equipped with an NC SPlan objective lens and a DP20 camera module (both from Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Scale bars represent 10 μm. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (E) CD41+ and CD41− cells were cultured in MethoCult M3434 medium and examined their colony-forming activities. Representative pictures of colonies and a bar graph showing colony numbers from each fraction are presented. Scale bars represent 500 μm. Error bars indicate SD (n = 8; **P < .01, Student t test). (F) The cell-cycle status of CD41+ and CD41− cells was analyzed by propidium iodide staining. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (G) Apoptosis analysis of CD41+ and CD41− cells. Freshly isolated BM-MNCs were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody, followed by staining with APC-conjugated Annexin V. Apoptotic rates in CD41+ and CD41− fractions were determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Student t test). (H) CD41+ and CD41− fractions were sorted from primary Evi1 leukemia BM cells and IV injected into sublethally irradiated (5.25 Gy) mice (1 × 104 cells per mouse). Survival curves of mice transplanted with CD41+ (n = 9; red line) or CD41− (n = 10; blue line) Evi1 leukemia cells are shown (P = .0016, log-rank test). (I-J) LIC frequencies in the 4 subfractions of Evi1 leukemia cells. (I) The GFP+/c-kit+ fraction in Evi1 leukemia BM cells was divided into 4 subfractions: Fr.1 (CD41+/CD150+), Fr.2 (CD41+/CD150−), Fr.3 (CD41−/CD150+), and Fr.4 (CD41−/CD150−). (J) LIC frequencies in each fraction as determined by a limiting dilution transplantation assay are shown. See supplemental Table 5 for detailed transplantation results.

CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells have a higher LIC than CD41− cells. (A) The surface expression of CD41 on Evi1 leukemia cells. BM- and SP-MNCs were harvested from Evi1 leukemia mice and stained with an allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody. Representative FACS data are shown. The graph shows frequencies of CD41+ cells in BM and SP derived from 9 individual leukemia mice. (B) Surface-marker profiles of Evi1 leukemia BM cells. Cells were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody and APC-conjugated antibodies (c-kit, CD150, Gr-1, or Mac-1). Data for GFP+ cells are shown. Bar graphs show frequencies of c-kit+, CD150+, Gr-1+, and Mac-1+ cells in CD41+ and CD41− fractions. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (C) CD41+ and CD41− Evi1 leukemia cells within a GFP+ fraction were sorted and subjected to further analysis. A representative FACS plot is shown. (D) The morphologic feature of CD41+ and CD41− cells was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining, and the proportion of myeloblasts with a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio was compared between these fractions. Pictures were captured by a BH-2 microscope equipped with an NC SPlan objective lens and a DP20 camera module (both from Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Scale bars represent 10 μm. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (E) CD41+ and CD41− cells were cultured in MethoCult M3434 medium and examined their colony-forming activities. Representative pictures of colonies and a bar graph showing colony numbers from each fraction are presented. Scale bars represent 500 μm. Error bars indicate SD (n = 8; **P < .01, Student t test). (F) The cell-cycle status of CD41+ and CD41− cells was analyzed by propidium iodide staining. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (G) Apoptosis analysis of CD41+ and CD41− cells. Freshly isolated BM-MNCs were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody, followed by staining with APC-conjugated Annexin V. Apoptotic rates in CD41+ and CD41− fractions were determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Student t test). (H) CD41+ and CD41− fractions were sorted from primary Evi1 leukemia BM cells and IV injected into sublethally irradiated (5.25 Gy) mice (1 × 104 cells per mouse). Survival curves of mice transplanted with CD41+ (n = 9; red line) or CD41− (n = 10; blue line) Evi1 leukemia cells are shown (P = .0016, log-rank test). (I-J) LIC frequencies in the 4 subfractions of Evi1 leukemia cells. (I) The GFP+/c-kit+ fraction in Evi1 leukemia BM cells was divided into 4 subfractions: Fr.1 (CD41+/CD150+), Fr.2 (CD41+/CD150−), Fr.3 (CD41−/CD150+), and Fr.4 (CD41−/CD150−). (J) LIC frequencies in each fraction as determined by a limiting dilution transplantation assay are shown. See supplemental Table 5 for detailed transplantation results.

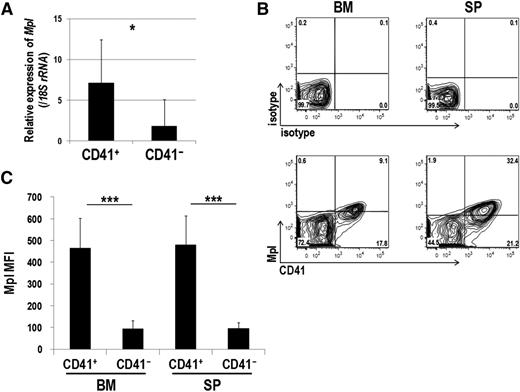

Mpl is predominantly expressed in CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells

As shown in Table 1, expression of several megakaryocytic markers correlated with that of EVI1. Because Mpl, the THPO receptor, is known as a well-defined molecule, we next tested whether Evi1 leukemia cells express Mpl. As shown in Figure 4A, CD41+ cells showed significantly higher Mpl expression than CD41− cells. FACS analysis confirmed that Mpl was mainly expressed in the CD41+ BM and SP cells (Figure 4B-C). We also assessed Mpl expression in other mouse models of myeloid leukemia induced by MLL-ENL and MOZ-TIF2 oncogenes. Our previous study showed that Evi1 expression in MLL-ENL leukemia mice varied among individuals,22 and MLL-ENL leukemia cells used here expressed low levels of Evi1 (supplemental Figure 4A). Evi1 expression was not detected in MOZ-TIF2 leukemia cells. These leukemia cells expressed neither Mpl nor CD41 (supplemental Figure 4B-C).

Mpl is predominantly expressed in CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Mpl expression was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in CD41+ and CD41− BM cells of Evi1 leukemia mice. BM-MNCs were harvested from 5 independent mice, and CD41+ and CD41− cells were sorted. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Student t test). (B-C) FACS analysis of CD41 and Mpl expression in BM- and SP-MNCs from Evi1 leukemia mice. (B) Cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD41 and Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti-mouse Mpl antibodies. Expression profiles were analyzed for GFP+ cells. (C) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Mpl was quantified in CD41+ and CD41− cells. Error bars indicate SD (n = 8; ***P < .001, Student t test).

Mpl is predominantly expressed in CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Mpl expression was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in CD41+ and CD41− BM cells of Evi1 leukemia mice. BM-MNCs were harvested from 5 independent mice, and CD41+ and CD41− cells were sorted. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Student t test). (B-C) FACS analysis of CD41 and Mpl expression in BM- and SP-MNCs from Evi1 leukemia mice. (B) Cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD41 and Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti-mouse Mpl antibodies. Expression profiles were analyzed for GFP+ cells. (C) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Mpl was quantified in CD41+ and CD41− cells. Error bars indicate SD (n = 8; ***P < .001, Student t test).

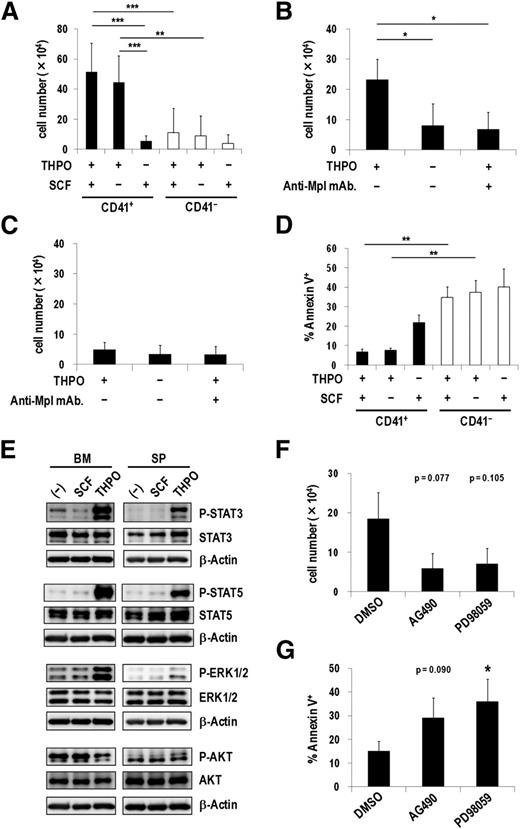

THPO/MPL signaling enhances the growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells

In the hematopoietic system, THPO plays an important role not only in regulating megakaryocytic development and platelet production but also in maintaining quiescent HSCs in the osteoblastic niche.25,26 Therefore, we next examined effects of THPO on CD41+ and CD41− Evi1 leukemia cells cultured on OP9 stromal cells. THPO but not SCF more efficiently stimulated the proliferation of CD41+ cells than CD41− cells (Figure 5A), which correlated well with the expression pattern of Mpl in these fractions. Moreover, the combination of THPO and SCF did not show any synergistic effect on cell growth, indicating that THPO is sufficient for the growth of CD41+ cells. Because CD41+ and CD41− cells produced each other to some extent during the culture on OP9 cells (data not shown), the clear effect of THPO on CD41+ cells might be masked by the gradual appearance of CD41− cells. An anti-Mpl neutralizing antibody, AMM2,26 distinctly inhibited the THPO-mediated growth of CD41+ cells but not CD41− cells (Figure 5B-C). In addition, CD41+ cells showed a significantly lower apoptotic rate than CD41− cells in the presence of THPO (Figure 5D). When CD41+ cells were cultured on OP9 feeder cells with or without THPO for 3 days, expression of Gr-1 and Mac-1 was not induced even in the absence of THPO (supplemental Figure 5), indicating that THPO might not inhibit differentiation of Evi1 leukemia cells. These results demonstrate that THPO/MPL signaling supports the proliferation and suppresses the apoptosis of the CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells.

THPO/MPL signaling enhances the growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Proliferation assays of CD41+ and CD41− BM cells from Evi1 leukemia mice using OP9 coculture system. CD41+ or CD41− cells (5 × 104 cells per well) were seeded onto a confluent layer of OP9 stromal cells in the presence of SCF and THPO, THPO alone, or SCF alone. After 7 days of culture, cells were harvested by trypsinization and the number of viable leukemia cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 7; **P < .01, ***P < .001, Tukey’s test). (B-C) The antiproliferation effect of an anti-Mpl antibody against CD41+ cells. CD41+ (B; n = 4) or CD41− (C; n = 3) cells were seeded onto OP9 stromal cells with or without THPO, or THPO with an anti-Mpl antibody (100 ng/mL), and cultured for 7 days. The number of viable cells was determined as described in panel A. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Dunnett’s test). (D) Apoptosis analysis of CD41+ and CD41− cells cocultured with OP9 cells. CD41+ or CD41− cells were cultured in the same condition as panel A. After 7 days culture, cells were harvested and stained with Annexin V, followed by FACS analysis. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; **P < .01, Tukey’s test). (E) BM- and SP-MNCs of Evi1 leukemia mice were serum-starved in α-MEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 60 minutes and then stimulated with SCF or THPO in α-MEM containing 0.1% BSA for 60 minutes. Unstimulated cells were used as negative controls. The phosphorylation levels of STAT3, STAT5, ERK1/2, and AKT were analyzed by western blotting. (F-G) CD41+ cells were treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle control, a JAK2 inhibitor (AG490; 20 μM), or an MEK inhibitor (PD98059; 20 μM) on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of THPO for 7 days. (F) The number of viable cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; Dunnett’s test). (G) The rate of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Dunnett’s test). The concentration of the cytokines used in these experiments was 50 ng/mL.

THPO/MPL signaling enhances the growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Proliferation assays of CD41+ and CD41− BM cells from Evi1 leukemia mice using OP9 coculture system. CD41+ or CD41− cells (5 × 104 cells per well) were seeded onto a confluent layer of OP9 stromal cells in the presence of SCF and THPO, THPO alone, or SCF alone. After 7 days of culture, cells were harvested by trypsinization and the number of viable leukemia cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 7; **P < .01, ***P < .001, Tukey’s test). (B-C) The antiproliferation effect of an anti-Mpl antibody against CD41+ cells. CD41+ (B; n = 4) or CD41− (C; n = 3) cells were seeded onto OP9 stromal cells with or without THPO, or THPO with an anti-Mpl antibody (100 ng/mL), and cultured for 7 days. The number of viable cells was determined as described in panel A. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Dunnett’s test). (D) Apoptosis analysis of CD41+ and CD41− cells cocultured with OP9 cells. CD41+ or CD41− cells were cultured in the same condition as panel A. After 7 days culture, cells were harvested and stained with Annexin V, followed by FACS analysis. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; **P < .01, Tukey’s test). (E) BM- and SP-MNCs of Evi1 leukemia mice were serum-starved in α-MEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 60 minutes and then stimulated with SCF or THPO in α-MEM containing 0.1% BSA for 60 minutes. Unstimulated cells were used as negative controls. The phosphorylation levels of STAT3, STAT5, ERK1/2, and AKT were analyzed by western blotting. (F-G) CD41+ cells were treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle control, a JAK2 inhibitor (AG490; 20 μM), or an MEK inhibitor (PD98059; 20 μM) on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of THPO for 7 days. (F) The number of viable cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3; Dunnett’s test). (G) The rate of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Dunnett’s test). The concentration of the cytokines used in these experiments was 50 ng/mL.

Upon THPO binding, MPL activates several intracellular signals including Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways. As shown in Figure 5E, STAT3, STAT5, and ERK1/2 were markedly phosphorylated in Evi1 leukemia cells stimulated with THPO but not SCF. In contrast, remarkable phosphorylation of AKT was not induced. Neither THPO nor SCF induced phosphorylation of these molecules in MLL-ENL leukemia cells that did not express Mpl (supplemental Figure 6). When CD41+ cells were treated with a JAK2 inhibitor (AG490) or an MEK inhibitor (PD98059), the number of viable cells decreased by approximately 50% compared with those treated with a vehicle control (Figure 5F). Furthermore, apoptotic cells increased more than 2-fold by addition of AG490 or PD98059 (Figure 5G). Similarly, a PI3K inhibitor, Ly294002, suppressed the growth and induced apoptosis of CD41+ cells (supplemental Figure 7), indicating that the PI3K/AKT pathway was actually activated in CD41+ cells. These results demonstrate that the JAK/STAT and MEK/ERK pathways are responsible for the growth-accelerating and antiapoptotic effects of THPO on CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells.

To test whether THPO/MPL signaling is important for the progression of Evi1 leukemia in vivo, we constructed a short hairpin RNA–expressing retroviral vector targeting Mpl, by which Mpl+ Evi1 leukemia cells decreased by about 50% (supplemental Figure 8A). Survival analysis revealed that short hairpin RNA–mediated knockdown of Mpl in Evi1 leukemia BM cells partially, but significantly, delayed the onset of Evi1 leukemia (supplemental Figure 8B).

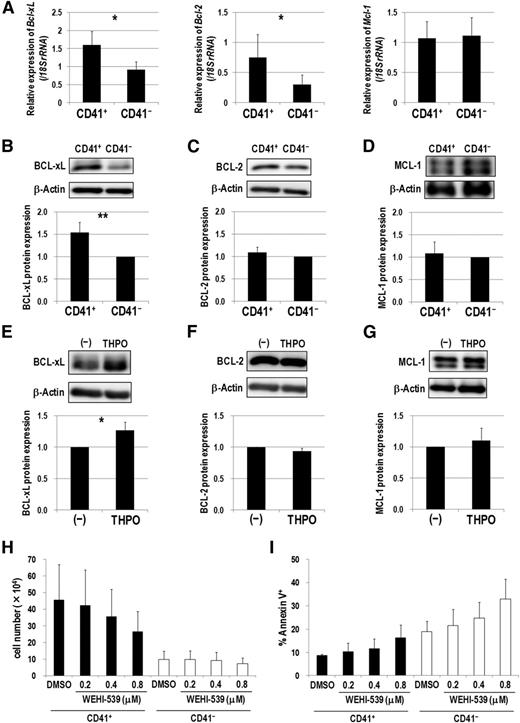

BCL-xL upregulation via THPO/MPL signaling supports CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells

Because THPO/MPL signaling enhanced the antiapoptotic property of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells, we next examined expression patterns of several antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family genes. CD41+ cells showed higher expression of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 than CD41− cells (Figure 6A). In contrast, Mcl-1 expression levels were comparable between these fractions. Furthermore, BCL-xL was more highly expressed in CD41+ cells at a protein level than in CD41− cells (Figure 6B). However, expression of BCL-2 and MCL-1 was comparable in these fractions (Figure 6C-D). After serum starvation and subsequent stimulation with THPO, the expression of BCL-xL, but not BCL-2 and MCL-1, was upregulated in Evi1 leukemia cells (Figure 6E-G). Finally, we examined whether WEHI-539, a highly specific BCL-xL inhibitor,27 exerts an inhibitory effect on Evi1 leukemia cells cultured on OP9 feeder cells. WEHI-539 inhibited the growth and induced apoptosis of CD41+ cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6H-I). On the contrary, the growth of CD41− cells was not affected by WEHI-539. These results indicate that THPO/MPL signaling supports the growth and survival of Evi1 leukemia cells via upregulating BCL-xL.

BCL-xL upregulation via THPO/MPL signaling supports the growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Comparison of Bcl-xL (left), Bcl-2 (middle), and Mcl-1 (right) mRNA expression between CD41+ and CD41− BM cells of Evi1 leukemia mice. CD41+ and CD41− BM cells were sorted from 5 independent mice. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Student t test). (B-D) Comparison of protein expression of BCL-xL (B), BCL-2 (C), and MCL-1 (D) between CD41+ and CD41− fractions by western blotting. Representative images and bar graphs showing quantified protein levels are presented. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin expression as the internal control and represented as relative values to those of CD41− cells. Quantification was performed by ImageJ software. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (E-G) Cryopreserved BM- or SP-MNCs from Evi1 leukemia mice were thawed and serum-starved in α-MEM containing 1% BSA for 3 hours, and then stimulated with or without THPO in α-MEM containing 0.1% BSA for 7 hours. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed for protein extraction. The expression levels of BCL-xL (E), BCL-2 (F), and MCL-1 (G) were determined by western blotting. Representative images and bar graphs showing quantified protein levels are presented. Quantification was performed as described above. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Student t test). (H-I) CD41+ or CD41− cells were treated with DMSO as a vehicle control or a BCL-xL inhibitor (WEHI-539; 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 μM) on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of THPO for 7 days. (H) The number of viable cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (I) The rate of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). Black and white bars represent the results from CD41+ and CD41− cells, respectively. There was no significant difference between DMSO- and WEHI-539-treated groups (Dunnett’s test). The concentration of THPO used in these experiments was 50 ng/mL.

BCL-xL upregulation via THPO/MPL signaling supports the growth and survival of CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells. (A) Comparison of Bcl-xL (left), Bcl-2 (middle), and Mcl-1 (right) mRNA expression between CD41+ and CD41− BM cells of Evi1 leukemia mice. CD41+ and CD41− BM cells were sorted from 5 independent mice. Expression levels relative to normal c-kit+ BM cells are presented. Error bars indicate SD (*P < .05, Student t test). (B-D) Comparison of protein expression of BCL-xL (B), BCL-2 (C), and MCL-1 (D) between CD41+ and CD41− fractions by western blotting. Representative images and bar graphs showing quantified protein levels are presented. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin expression as the internal control and represented as relative values to those of CD41− cells. Quantification was performed by ImageJ software. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5; **P < .01, Student t test). (E-G) Cryopreserved BM- or SP-MNCs from Evi1 leukemia mice were thawed and serum-starved in α-MEM containing 1% BSA for 3 hours, and then stimulated with or without THPO in α-MEM containing 0.1% BSA for 7 hours. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed for protein extraction. The expression levels of BCL-xL (E), BCL-2 (F), and MCL-1 (G) were determined by western blotting. Representative images and bar graphs showing quantified protein levels are presented. Quantification was performed as described above. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4; *P < .05, Student t test). (H-I) CD41+ or CD41− cells were treated with DMSO as a vehicle control or a BCL-xL inhibitor (WEHI-539; 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 μM) on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of THPO for 7 days. (H) The number of viable cells was counted. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (I) The rate of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). Black and white bars represent the results from CD41+ and CD41− cells, respectively. There was no significant difference between DMSO- and WEHI-539-treated groups (Dunnett’s test). The concentration of THPO used in these experiments was 50 ng/mL.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the expression of ITGA2B and MPL positively correlated with that of EVI1 in AML patients and that a subfraction of BM and SP cells derived from Evi1 leukemia mice expressed both CD41 and Mpl. Several lines of evidence demonstrated that CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells not only contain immunophenotypically and functionally more immature cells but also exert a higher LIC in serial transplantation assays than CD41− cells. Moreover, the fact that THPO/MPL signaling supported the growth and survival of CD41+ cells provides the novel molecular pathogenesis of Evi1 leukemia.

It has been shown that the THPO/MPL pathway is involved in leukemogenesis as well as megakaryopoiesis.28 According to studies using primary AML samples, Mpl is expressed in 50% to 60% of AML cases,29-32 and the majority of AML myeloblasts expressing Mpl proliferate in vitro in response to THPO.29,30 In addition, inappropriately low levels of serum-circulating THPO, which recovered after effective chemotherapy, were reported in Mpl+ AML patients, indicating that THPO is bound to Mpl+ leukemia cells to promote their growth in vivo.33 Recent reports that Mpl expression is upregulated in human AML cells harboring chromosomal translocation t(8;21)(q22;q22), which generates the AML1-ETO fusion gene, and THPO/MPL signaling enhances their growth and self-renewing capacity further explain the biological relevance of this pathway in leukemogenesis.34,35 In these AML1-ETO leukemia models, the JAK/STAT and PI3K/AKT pathways rather than the MEK/ERK pathway are important downstream cascades of THPO/MPL signaling. In contrast, all 3 pathways were involved in the growth and survival of Evi1 leukemia cells, although AKT activation was not induced by THPO. Because Evi1 activates PI3K/AKT signaling by downregulating PTEN,13 PTEN repression may have a predominant effect on AKT activation under the Evi1-overexpressed condition, compared with MPL-mediated activation of AKT. These findings indicate that the regulation of molecular networks downstream of MPL signaling varies in different cellular contexts. Importantly, upregulation of BCL-xL through THPO/MPL signaling plays an essential role in sustaining the viability of normal megakaryocytes and leukemia cells carrying t(8;21)(q22;q22).28,34,36 Here, we demonstrated that BCL-xL expression was enhanced in CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells upon THPO stimulation and that pharmacologic inhibition of BCL-xL suppressed their growth and survival in vitro. Therefore, we suppose that the THPO/MPL/BCL-xL cascade may serve as a common oncogenic driver for Mpl+ AML cases irrespective of cytogenetics or prognostic subclasses of AML.

Despite the significance for CD41+ Evi1 leukemia cells, the THPO/MPL pathway seems to be dispensable for their growth in the semisolid culture system, because MethoCult M3434 used here does not contain THPO (Figure 3E). Moreover, addition of THPO to M3434 did not enhance the colony-forming activity of CD41+ or CD41− cells (data not shown), raising the possibility that dependence on THPO/MPL signaling of Evi1 leukemia cells is reduced under a semisolid culture condition. The observation that Mpl expression on them was not maintained in M3434 culture (data not shown) may support this idea.

In Evi1 leukemia mice, c-kit+ cells were divided into 4 subfractions on the basis of CD41 and CD150 expression patterns (Figure 3I). The limiting dilution transplantation assay unveiled that not only CD41+ fractions (Fr.1 and Fr.2) but also CD41−/CD150+ cells (Fr.3) exhibited a high LIC (Figure 3J), which may explain the result that half of mice transplanted with CD41− cells developed AML after longer latency than those transplanted with CD41+ cells (Figure 3H). However, it is still unclear what molecular mechanism(s) confers such a strong LIC to leukemia cells in Fr.3. When precisely examined by FACS, Mpl expression was significantly higher in Fr.3 than in CD41−/CD150− cells (Fr.4) (supplemental Figure 9), suggesting that THPO/MPL signaling may be also involved in an enhanced LIC of leukemia cells in Fr.3.

In our AML mouse model, Evi1 leukemia cells clearly expressed Mpl. It should be noted, however, that Mpl expression decreases in hematopoietic cells of another mouse model in which transduction of the human EVI1 gene causes myelodysplastic syndrome.37 In that model, Evi1 physically interacts with Gata1 to suppress the transcription of Mpl and the erythropoietin receptor, Epor.38,39 Therefore, it is still controversial whether Evi1 upregulates or downregulates Mpl expression. One of the major differences between these mouse models is the species of Evi1 gene, that is, human EVI1 and mouse Evi1 are used for induction of myelodysplastic syndrome and AML, respectively. Laricchia-Robbio et al proved that the proximal zinc-finger domain (especially the first and sixth zinc fingers) of human Evi1 is crucial for direct interaction with Gata1.38 Although mouse Evi1 used in this study also possesses a putative proximal zinc-finger domain equivalent to that of human Evi1, it is as yet unclear whether mouse Evi1 can repress Gata1 function through protein-protein interaction. From the perspective of Gata1 gene expression, Gata1 expression was upregulated in Evi1 leukemia BM cells, compared with that in normal c-kit+ BM cells (data not shown). Given the fact that transcription of Gata1 is positively regulated by Gata1 itself,40 it is unlikely that Gata1 is counteracted by Evi1 in our mouse model. However, we cannot exclude another possibility that expression of Mpl and Gata1 is controlled in a disease-stage–specific manner in the process of developing Evi1 leukemia. As shown in Figure 3H, leukemic symptoms emerged after a relatively longer latency (over 150 days) in primary transplantation assays, suggesting that disease phenotype in earlier time points after transplantation may be different from that in the later leukemic stage. Therefore, monitoring of Gata1 and Mpl expression along with disease progression will help us elucidate how their expression is regulated in Evi1-overexpressed context.

It is not yet clear how Evi1 induces expression of megakaryocytic marker genes. According to published chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data of human ovarian carcinoma cells transduced with human EVI1, the Evi1-bound peak was found in the MPL gene locus between exons 10 and 11,41 raising a possibility that Evi1 could directly bind to this locus to activate MPL expression via unidentified transcriptional machineries. With regard to the ITGA2B gene, we found Evi1-binding sites in neither the above chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data set nor the in silico search by rVISTA2.0 (http://rvista.dcode.org/) (data not shown). Otherwise, Evi1 may regulate expression of key transcription factor(s) or physically interact with various epigenetic modifiers to increase ITGA2B expression. Very recently, it was reported that a distinct HSC subset exists that is biased toward the generation of CD41+ megakaryocyte progenitors, whose maintenance depends on THPO.42 Accordingly, Evi1 transduction might deregulate epigenetic status of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to make them partly similar to such a platelet-biased HSC fraction, resulting in the increased generation of CD41+ transformed cells.

In megakaryocytes and platelets, CD41 and CD61 form a heterodimer and function as a receptor for several extracellular matrices such as fibronectin, vitronectin, and fibrinogen. For example, fibrinogen localized at vascular sinusoids in BM stimulates megakaryocytes through CD41/CD61 to induce proplatelet formation.43 MWReg30, used here as an anti-mouse CD41 antibody, is known to block the function of CD41 on platelets and megakaryocytes.43,44 Gekas and Graf45 reported that MWReg30-treated murine HSCs show impaired long-term repopulation ability in vivo, suggesting that CD41/CD61 signaling is involved in homing and lodging of normal HSCs in BM. However, we could not obtain clear evidence that CD41/CD61 is crucial for Evi1-mediated leukemogenesis, because CD41+ cells stained with MWReg30 retained the capacity to induce secondary leukemia (Figure 3H) and showed a homing capacity to BM and SP equivalent to that of CD41− cells (supplemental Figure 3). In addition, we found that the progression of AML was not delayed when Evi1 leukemia cells in which surface CD41 expression was partially interfered by an Itga2b-knockdown vector were transplanted into mice (data not shown). Thus, CD41/CD61 signaling might be dispensable for proliferation or homing of Evi1 leukemia cells in vivo.

Several clinical studies reported that CD41 or CD61 expression is detected by FACS or immunohistochemistry in a subset of AML specimens with 3q abnormalities.46-50 Therefore, we examined CD41 expression by FACS using 4 primary AML samples, one carrying a t(3;3) translocation and the others carrying an MLL-rearrangement. Among them, CD34+ cells derived from the t(3;3) patient and 1 MLL-rearranged patient more frequently expressed CD41 than those from the others (supplemental Figure 10A). Interestingly, CD34+ cells of these 2 patients clearly expressed EVI1 (supplemental Figure 10B-C). Further investigation using more clinical samples with EVI1 expression will be needed to confirm the relationship between Evi1 and CD41.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Morishita for providing Evi1 complementary DNA, R. Ono and T. Nosaka for MLL-ENL complementary DNA, I. Kitabayashi for MOZ-TIF2 cDNA, T. Nakamura for pMYs-mouse Evi1-IRES-GFP, T. Kitamura for Plat-E packaging cells, and Y. Shimamura, F. Kaminaga, M. Yamamoto, M. Kobayashi, and the late Y. Sawamoto for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI grant number 24249055).

Authorship

Contribution: S.N., S.A., N.W.-O., and M.K. designed the study; S.N. performed most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript; S.A. and N.W.-O. assisted with several studies and participated in writing the manuscript; Y.M., Y.K., and T.T. supported some experiments and reviewed the manuscript; and M.K. supervised the entire study and participated in writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.K. has received research funding and honoraria for lectures from Kyowa Hakko Kirin. S.N. is employed by Kyowa Hakko Kirin. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mineo Kurokawa, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan; e-mail: kurokawa-tky@umin.ac.jp.