Key Points

Repeated plasma exchange removes sufficient HIT-IgG to achieve negative SRA despite ongoing strong-positive EIA.

Serially-diluted HIT sera tested in both SRA and EIA show that SRA negativity can be achieved with minimal decrease in EIA reactivity.

Abstract

Repeated therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) has been advocated to remove heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) IgG antibodies before cardiac/vascular surgery in patients who have serologically-confirmed acute or subacute HIT; for this situation, a negative platelet activation assay (eg, platelet serotonin-release assay [SRA]) has been recommended as the target serological end point to permit safe surgery. We compared reactivities in the SRA and an anti-PF4/heparin IgG-specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA), testing serial serum samples in a patient with recent (subacute) HIT who underwent serial TPE precardiac surgery, as well as for 15 other serially-diluted HIT sera. We observed that post-TPE/diluted HIT sera—when first testing SRA-negative—continue to test strongly positive by EIA-IgG. This dissociation between the platelet activation assay and a PF4-dependent immunoassay for HIT antibodies indicates that patients with subacute HIT undergoing repeated TPE before heparin reexposure should be tested by serial platelet activation assays even when their EIAs remain strongly positive.

Introduction

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is an adverse drug reaction caused by platelet-activating IgG antibodies that recognize multimolecular PF4/heparin complexes.1 Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) has been recommended as a way to remove HIT antibodies quickly, as might be required to permit administration of heparin for urgent cardiac surgery.2 However, HIT antibodies (IgG) are not as effectively removed by TPE as IgM.3 Using serial pre-/post-TPE sera obtained from a patient with subacute HIT (ie, recent HIT with platelet count recovery but persisting HIT antibodies4 ) who underwent repeated TPE pre-cardiac surgery, we compared antibody reactivity by the 14C-serotonin-release assay (SRA)5 —a functional (platelet activation) test for HIT antibodies—vs an IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin enzyme-immunoassay (EIA).6 We found that although a negative SRA could be achieved quickly post-TPE, corresponding EIA reactivities remained strongly positive. This observation proved to be a general feature of HIT antibody reactivity, because 15 other acute HIT sera showed rapid diminution of SRA reactivity upon serial dilutions, but with major reductions in EIA reactivity requiring much greater sample dilutions.

Case report

A 76-year-old female with renal carcinoma invading the inferior vena cava (IVC)/right atrium developed HIT without thrombosis (4Ts score,7 6 points), with strong-positive SRA and EIA, and with uneventful platelet count recovery during fondaparinux 7.5 mg therapy once daily subcutaneously. Cardiac surgery was scheduled 3 months post-HIT for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and removal of IVC/intracardiac tumor thrombus. However, because her SRA and EIA remained strongly positive (99% serotonin release at 0.3 IU/mL unfractionated heparin [UFH]; IgG-specific EIA, 2.58 optical density [OD] units), TPE was performed on 4 consecutive days (3-L exchanges with 5% albumin replacement), yielding a persistently negative SRA postsecond TPE, despite the EIA-IgG remaining strongly positive (1.85 OD units postsecond apheresis vs 2.30 OD units on serum obtained immediately before). Two days postfourth TPE, she received UFH (30 000 units intraoperatively) for cardiopulmonary bypass, undergoing: quadruple CABG, IVC/intracardiac tumor thrombectomy, and radical nephrectomy. Unfortunately, tumor removal was incomplete, and intraoperative splenic injury resulted in major blood loss, requiring splenectomy in massive transfusion setting (16 U red blood cells, 10 frozen plasma, 10 cryoprecipitate, 3 U platelets). The preoperative platelet count was 141 × 109/L, with an intraoperative nadir of 48 × 109/L. Postoperatively, daily fondaparinux 2.5 mg and aspirin 81 mg were given. Complications included complex-partial seizures (computed tomography brain scan was negative for thrombotic or hemorrhagic stroke) and ileus/aspiration pneumonitis on postoperative day 6. She was discharged on postoperative day 34.

Methods

Testing for HIT antibodies was performed using the SRA and an in-house anti-PF4/heparin IgG-specific EIA (McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory), as described previously.5,6 Serial serum samples were drawn for HIT antibody testing immediately before and after each TPE session. SRA-positive control sera obtained from 15 different patients previously diagnosed with HIT (each serum yielding >50% serotonin release at 0.3 U/mL UFH) were tested in fourfold serial dilutions (1/5 to 1/5120). The SRAs were performed over 2 days, and the EIA-IgG in 1 day using 3 plates, with internal HIT-positive and -negative control sera producing expected results. For comparison, sera are usually diluted 1 in 5 (final) in our SRA and 1 in 50 (final) in our EIA-IgG. Statistical analysis was performed by Student t test, paired 2-sample for means (Microsoft Excel 1997-2003). The patient provided written consent to report her case, and permission was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board to perform the studies using HIT-positive sera.

Results and discussion

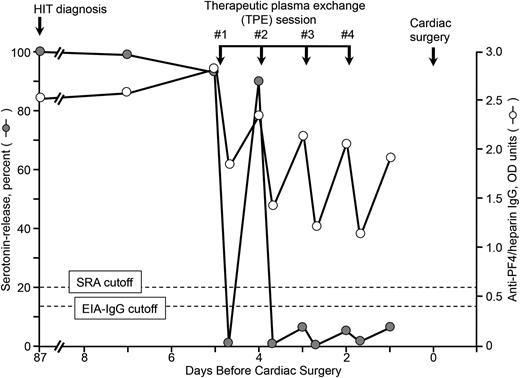

Figure 1 shows the percent serotonin release (at 0.3 IU/mL UFH) induced by the patient’s sera obtained at different time points precardiac surgery (cardiac surgery, day 0; HIT diagnosis, day –87), as well as immediately before/after each of 4 TPE sessions (days –5 through –2). We found that the EIA-IgG reactivity—expressed in OD units—abruptly fell after each TPE session (by a mean of 0.94 U; P < .001), but by the following day, EIA-IgG reactivity had risen significantly once again (by mean of 0.69 U; P = .0025). These observations are consistent with the partial removal of IgG antibodies by TPE, with subsequent redistribution of IgG from the extravascular/interstitial spaces into the intravascular compartment.3 Nevertheless, TPE was sufficient in our patient to remove IgG antibodies to a meaningful extent, as indicated by the negative SRA.

Serial SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA test results in relation to 4 therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) sessions performed on 4 consecutive days (last TPE performed 2 days before cardiac surgery using heparin). Heparin rechallenge during cardiac surgery did not result in increased levels of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies during the postoperative period (testing until postoperative day 7) (not shown). Although at the time of initial HIT diagnosis, the patient also had detectable anti-PF4/heparin antibodies of IgA class (EIA-IgA = 1.20 OD U; normal <0.45 U) and IgM class (EIA-IgM = 0.46 U; normal <0.45 U), both the IgA and IgM EIAs were negative 3 months later pre-TPE (0.30 and 0.34 OD U, respectively). EIA-IgG, enzyme-immunoassay (IgG-specific); OD, optical density; SRA, serotonin-release assay.

Serial SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA test results in relation to 4 therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) sessions performed on 4 consecutive days (last TPE performed 2 days before cardiac surgery using heparin). Heparin rechallenge during cardiac surgery did not result in increased levels of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies during the postoperative period (testing until postoperative day 7) (not shown). Although at the time of initial HIT diagnosis, the patient also had detectable anti-PF4/heparin antibodies of IgA class (EIA-IgA = 1.20 OD U; normal <0.45 U) and IgM class (EIA-IgM = 0.46 U; normal <0.45 U), both the IgA and IgM EIAs were negative 3 months later pre-TPE (0.30 and 0.34 OD U, respectively). EIA-IgG, enzyme-immunoassay (IgG-specific); OD, optical density; SRA, serotonin-release assay.

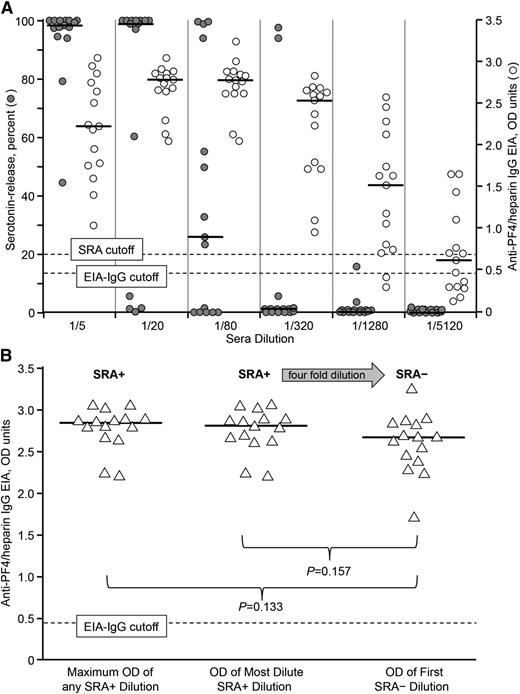

Figure 2A shows SRA and EIA-IgG results for 15 serially diluted HIT sera. The data show that samples testing SRA-negative can still have strongly positive EIA-IgG reactivities. For example, at a 1 in 320 sample dilution, only 2 of 15 HIT sera tested SRA-positive, whereas all 15 corresponding EIAs tested positive (and most strongly positive), with a median OD (interquartile range) of 2.55 (1.77, 2.65). Further, when we compared the corresponding EIAs for the most dilute (but still SRA-positive) sera vs the corresponding fourfold more dilute (but now SRA-negative) sera, the mean OD values were similar (2.75 vs 2.60, respectively; P = .157) (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the maximum OD reactivity (at any dilution) was similar to the OD reactivity of the most diluted, but still SRA-positive sample.

Comparative studies in the SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA using serially-diluted HIT sera. (A) Known HIT sera (n = 15) diluted from 1 in 5 to 1 in 5120 were tested in the SRA and EIA. (The 1/5 dilution in the SRA—20 μL patient serum to 80 μL washed platelets with heparin added—represents the standard conditions in the SRA.) Typical assay cutoffs are shown with dashed lines. Horizontal lines indicate median values. Compared with standard assay conditions, serial sample dilution generally results in a negative SRA well before a negative EIA result is attained. (B) Individual IgG-specific EIA ODs are shown for the same 15 HIT sera in 3 groupings: SRA+ showing maximum OD of any SRA+ dilution (leftmost data points); SRA+ showing OD of the most dilute yet still SRA+ serum dilution (middle data points); and SRA– showing OD of the first SRA– dilution (rightmost data points). There is a fourfold serum dilution between the 2 rightmost data sets. No significant differences were observed between the SRA+ and SRA– data sets. EIA-IgG, enzyme-immunoassay (IgG-specific); OD, optical density; PF4, platelet factor 4; SRA, serotonin-release assay; SRA–, SRA-negative; SRA+, SRA-positive.

Comparative studies in the SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA using serially-diluted HIT sera. (A) Known HIT sera (n = 15) diluted from 1 in 5 to 1 in 5120 were tested in the SRA and EIA. (The 1/5 dilution in the SRA—20 μL patient serum to 80 μL washed platelets with heparin added—represents the standard conditions in the SRA.) Typical assay cutoffs are shown with dashed lines. Horizontal lines indicate median values. Compared with standard assay conditions, serial sample dilution generally results in a negative SRA well before a negative EIA result is attained. (B) Individual IgG-specific EIA ODs are shown for the same 15 HIT sera in 3 groupings: SRA+ showing maximum OD of any SRA+ dilution (leftmost data points); SRA+ showing OD of the most dilute yet still SRA+ serum dilution (middle data points); and SRA– showing OD of the first SRA– dilution (rightmost data points). There is a fourfold serum dilution between the 2 rightmost data sets. No significant differences were observed between the SRA+ and SRA– data sets. EIA-IgG, enzyme-immunoassay (IgG-specific); OD, optical density; PF4, platelet factor 4; SRA, serotonin-release assay; SRA–, SRA-negative; SRA+, SRA-positive.

Our observations have implications for managing patients with (sub)acute HIT using TPE before planned heparin reexposure. Previous American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) consensus conference guidelines on HIT management published in 20088 recommended that patients with previous HIT can receive UFH provided that heparin-dependent, platelet-activating antibodies are no longer detectable by (washed) platelet activation assay, even if the EIA remains positive (a recommendation based on favorable outcomes among EIA-positive/[washed platelet] activation assay–negative patients who were reexposed to heparin for urgent cardiac surgery9,10 ), and we followed this approach to manage our patient. (Although the 2012 ACCP guidelines11 also recommend heparin use with “heparin antibodies … absent,” the applicable assays are not specified.) Although SRA-negative status usually occurs within a few weeks post-HIT,12 when surgery is required urgently yet SRA-positive status persists, TPE becomes an important option.2,8,11 Our studies of serial pre-/post-TPE serum (Figure 1), as well as corroborative studies using serially-diluted HIT sera (Figure 2A-B), demonstrate that EIAs usually remain strongly positive, even when a patient is otherwise at acceptable risk for heparin reexposure (per negative washed-platelet activation assay). Although our findings might appear surprising—given the known predictivity for a positive SRA with increasing strength of EIA reactivity13-15 –they point to the critical dependence of HIT serum–induced platelet activation to a crucial threshold level of platelet-activating antibodies (a phenomenon that helps to explain the EIA-SRA interrelationship13-15 ), and how quickly platelet-activating properties can be lost in an individual patient with declining antibody levels, either occurring naturally over time9,10,12 or by serum dilution performed experimentally or via TPE. Our observations also help to explain the serological profiles of 2 previously reported patients (patient 1/Figure 1A in reference 9, and patient 20/Figure 3 in reference 10) with recent HIT undergoing serosurveillance to assess readiness for heparin reexposure: consistent with our findings, these patients continued to have strong positive anti-PF4/heparin antibodies by EIA (with values similar to the highest ones obtained at HIT diagnosis), even when their sera had become negative by washed-platelet activation assay.9,10

In summary, our observations indicate that diluted HIT serum—whether achieved clinically through serial TPE, or experimentally through serial sample dilutions—demonstrates loss of SRA reactivity well before a decrease in EIA reactivity. These findings point to the importance of performing platelet activation assays in parallel with the EIA, when testing pre- and post-TPE samples when judging patient suitability for a planned heparin reexposure.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Anand Padmanabhan, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, for reviewing the manuscript and providing helpful comments.

Authorship

Contribution: T.E.W. designed and supervised the experiments, analyzed the data, and interpreted the results; J.-A.I.S. designed and performed the experiments and interpreted the results; T.E.W., F.V.C., A.K., and A.G. helped to manage the patient using some of the data obtained in this report; M.A.C. provided the initial concept for the study; and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.E.W. has received lecture honoraria from Pfizer Canada and Instrumentation Laboratory, has provided consulting services to and/or has received research funding from W.L. Gore, and has provided expert witness testimony relating to HIT. M.A.C. has sat on advisory boards for Janssen, Leo Pharma, Portola, and AKP America. He holds a Career Investigator award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, and the Leo Pharma Chair in Thromboembolism Research at McMaster University. His institution has received funding for research projects from Leo Pharma. M.A.C. has received lecture honoraria from Leo Pharma, Bayer, Celgene, Shire, and CSL Behring and has provided expert testimony (but not in cases involving HIT). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ted Warkentin, Room 1-270B, Hamilton General Hospital, 237 Barton St East, Hamilton, ON, L8L 2X2 Canada; e-mail: twarken@mcmaster.ca.