Key Points

We describe the first knockout mouse model for RIAM.

In contrast to previous studies using cell culture approaches, platelets from RIAM-null mice show normal integrin activation and function.

Abstract

Platelet aggregation at sites of vascular injury is essential for hemostasis but also thrombosis. Platelet adhesiveness is critically dependent on agonist-induced inside-out activation of heterodimeric integrin receptors by a mechanism involving the recruitment of talin-1 to the cytoplasmic integrin tail. Experiments in heterologous cells have suggested a critical role of Rap1-guanosine triphosphate-interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM) for talin-1 recruitment and thus integrin activation, but direct in vivo evidence to support this has been missing. We generated RIAM-null mice and found that they are viable, fertile, and apparently healthy. Unexpectedly, platelets from these mice show unaltered β3- and β1-integrin activation and consequently normal adhesion and aggregation responses under static and flow conditions. Similarly, hemostasis and arterial thrombus formation were indistinguishable between wild-type and RIAM-null mice. These results reveal that RIAM is dispensable for integrin activation and function in mouse platelets, strongly suggesting the existence of alternative mechanisms of talin-1 recruitment.

Introduction

Platelet adhesion and aggregation are essential for hemostasis; however, uncontrolled aggregation responses in injured vessels can cause life-threatening disease states such as myocardial infarction or stroke.1,2 These processes are mediated by heterodimeric receptors of the β1- and β3-integrin families.3 In resting platelets, integrins are expressed in a low-affinity state, but in response to cellular activation they shift to a high-affinity state and efficiently bind their ligands, most notably components of the extracellular matrix and other receptors.3-5 This so-called inside-out activation is triggered by the binding of talin-1 and kindlins to NPYX motifs at the intracellular tail of the integrin β-subunit.6-8 The mechanisms of talin-1 recruitment to integrins have been extensively studied, and the small GTPase Rap1 and its downstream effector Rap1-guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM) have been implicated therein.9-12 RIAM, a member of the Mig-10/RIAM/lamellipodin family, contains a Ras-association and an adjacent pleckstrin homology domain, which suggests that it serves as a proximity detector for Rap1-GTP and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphates.13 Thus, RIAM and bound talin-1 are located to membrane microdomains rich in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphates, which has been shown to increase binding of talin-1 to the β-integrin subunit and ultimately lead to integrin activation.13 An important role of RIAM in platelet αIIbβ3-integrin activation has been demonstrated in different overexpression and knockdown studies in mammalian cell lines, but also in primary mouse megakaryocytes.9-11,14 However, direct evidence of a role for RIAM in platelet integrin activation has not been provided.

Study design

Animals

Animal studies were approved by the district government of Lower Franconia (Bezirksregierung Unterfranken). Apbb1ip+/− mice were generated by injection of embryonic stem cell clone 16066A-D5 (KOMP; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site) into C57Bl/6 blastocysts. Germ-line transmission was obtained by backcrossing the resulting chimeric mice with C57Bl/6 mice.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.15 RIAM (1 μg mL−1, EP2806; Epitomics) and β-actin (1 μg mL−1, #4970; Cell Signaling) were probed with the respective antibodies.

Flow cytometry, platelet preparation, aggregometry, and spreading

Platelet count, size, and activation of β3- (JON/A-PE; Emfret) and β1-integrins (9EG7-FITC; BD Pharmingen), as well as surface exposure of α2-, α5-, β1-, αIIb-, and β3-integrins, were determined by flow cytometry as previously described.6,7 Preparation of platelets, turbidometric aggregometry, and platelet spreading have been described elsewhere.6,7,15,16

Clot retraction and platelet adhesion under flow

Tail bleeding time and in vivo thrombus formation

Data analysis

The presented results are mean ± standard deviation from ≥3 independent experiments per group, if not otherwise stated. Differences between control and RIAM-null mice were statistically analyzed using the Student t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

RIAM-null mice are viable and healthy

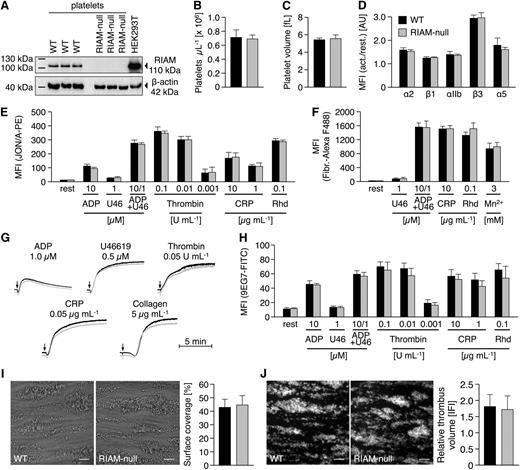

We targeted the Apbb1ip gene (supplemental Figure 1) by applying a VelociGene Definitive Null Allele Design, where exons 3 to 6 of the Apbb1ip gene were replaced with a LacZ-p(A); Neo-p(A) cassette by homologous recombination, thus abolishing Apbb1ip expression. Apbb1ip+/− mice were intercrossed to obtain Apbb1ip−/− (referred to as RIAM-null) and the respective control mice. RIAM-null mice were born at a normal Mendelian ratio, viable, and fertile, and appeared overall healthy. Western blot analysis confirmed strong expression of RIAM in control but not in RIAM-null platelets (Figure 1A). Platelet counts (Figure 1B), size (Figure 1C), and the distribution of red and white blood cells (data not shown) were indistinguishable from controls, suggesting that RIAM is not essential for hematopoiesis.

Unaltered inside-out activation of integrins in RIAM-null platelets. (A) Western blot analysis reveals the absence of RIAM protein (Epitomics, EP2806; 110 kDa) in RIAM-null platelets. (B) Unaltered platelet number and (C) size in RIAM-deficient mice as assessed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences) and with a standard blood cell analyzer (Sysmex). (D) Integrins are normally recruited to the surface of RIAM-null platelets upon stimulation with thrombin (0.01 U mL−1). Unaltered activation of platelet (E) αIIbβ3-integrin (JON/A-PE) translates into normal (F) fibrinogen-binding and (G) aggregation responses of RIAM-null platelets as determined by (D-F) flow cytometry or (G) turbidometric aggregometry (APACT). For aggregation studies with thrombin, collagen-related peptide (CRP), collagen, and U46619 washed platelets (1.5 × 105 platelets per μL) were used; aggregation studies with ADP were performed in platelet-rich plasma (1.5 × 105 platelets per μL). U46, U46619, a stable thromboxane A2 analog; Rhd, rhodocytin. Activation of platelet (H) β1-integrin (9EG7-FITC), as well as (I) adhesion and (J) thrombus formation of RIAM-null platelets under flow (1000 s−1) on collagen I (100 μg mL−1) was indistinguishable from wild-type controls. Images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (40×/0.6 oil objective). Scale bars in I and J represent 25 µm. (B-F,H-J) Values are mean ± standard deviation. Curves in G represent light transmission over time, with platelet-rich plasma set as 0% and platelet-poor plasma as 100% aggregation. The presented results are representative of ≥3 independent experiments with at least n = 3 vs 3 individuals per group.

Unaltered inside-out activation of integrins in RIAM-null platelets. (A) Western blot analysis reveals the absence of RIAM protein (Epitomics, EP2806; 110 kDa) in RIAM-null platelets. (B) Unaltered platelet number and (C) size in RIAM-deficient mice as assessed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences) and with a standard blood cell analyzer (Sysmex). (D) Integrins are normally recruited to the surface of RIAM-null platelets upon stimulation with thrombin (0.01 U mL−1). Unaltered activation of platelet (E) αIIbβ3-integrin (JON/A-PE) translates into normal (F) fibrinogen-binding and (G) aggregation responses of RIAM-null platelets as determined by (D-F) flow cytometry or (G) turbidometric aggregometry (APACT). For aggregation studies with thrombin, collagen-related peptide (CRP), collagen, and U46619 washed platelets (1.5 × 105 platelets per μL) were used; aggregation studies with ADP were performed in platelet-rich plasma (1.5 × 105 platelets per μL). U46, U46619, a stable thromboxane A2 analog; Rhd, rhodocytin. Activation of platelet (H) β1-integrin (9EG7-FITC), as well as (I) adhesion and (J) thrombus formation of RIAM-null platelets under flow (1000 s−1) on collagen I (100 μg mL−1) was indistinguishable from wild-type controls. Images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (40×/0.6 oil objective). Scale bars in I and J represent 25 µm. (B-F,H-J) Values are mean ± standard deviation. Curves in G represent light transmission over time, with platelet-rich plasma set as 0% and platelet-poor plasma as 100% aggregation. The presented results are representative of ≥3 independent experiments with at least n = 3 vs 3 individuals per group.

Unaltered inside-out integrin activation in RIAM-null platelets

Flow cytometric analyses showed that control and RIAM-null platelets display comparable surface expression levels of β1- and β3-integrins both under resting conditions and upon stimulation with thrombin (Figure 1D). Next, agonist-induced αIIbβ3-integrin activation was determined using the JON/A-PE antibody19 and, remarkably, found to occur with the same efficiency in RIAM-null and wild-type platelets in response to all tested agonists (Figure 1E). Similar results were obtained for the binding of Alexa F488-conjugated fibrinogen (Figure 1F). These results were entirely unexpected given previous studies where a knockdown of RIAM was associated with impaired cell adhesion and αIIbβ3-integrin activation.9-11 Of note, we also performed time course experiments for platelet fibrinogen binding and obtained comparable results at all tested time points for control and mutant platelets, strongly suggesting that integrin disengagement is not affected by RIAM deficiency (Figure 1F; data not shown). In agreement with these data, RIAM-null platelets displayed normal aggregation responses to different agonists (Figure 1G). Besides αIIbβ3-integrins, RIAM has been implicated in β1-integrin activation and adhesion of Jurkat T-cells.14 However, activation of β1-integrins, as assessed by binding of the 9EG7 antibody,20 was comparable between RIAM-null and control platelets (Figure 1H). Consistently, RIAM-null platelets showed normal adhesion (Figure 1I) and aggregate formation (Figure 1J) on collagen in a flow adhesion assay, which is known to be highly dependent on functional α2β1 integrins.6,7,21

Platelet outside-in signaling is not affected by RIAM deficiency

RIAM has recently been implicated in integrin outside-in signaling in melanoma cells.22,23 To assess the role of RIAM in integrin outside-in signaling in platelets, we allowed control and RIAM-null platelets to spread on fibrinogen but found no differences in adhesion, extent, or kinetics of spreading (Figure 2A) or cytoskeletal rearrangements (Figure 2B). Likewise, integrin outside-in signaling-dependent clot retraction was indistinguishable between wild-type and RIAM-null mice (Figure 2C-D), excluding an essential role of RIAM in this process.

RIAM deficiency does not affect platelet outside-in signaling and in vivo thrombus formation. RIAM-null platelets display a normal (A) spreading and (B) reorganization of the actin (red, Phalloidin Atto647N) and tubulin (green, α-tubulin-Alexa F488) cytoskeleton on a fibrinogen-coated (100 μg mL−1) surface. Values in A represent mean. Images in B were acquired with a TCS SP5 confocal microscope (100×/1.4 oil STED objective; Leica Microsystems). Scale bars represent 3 µm. (C-D) Platelet clot retraction of RIAM-null platelets was indistinguishable from wild-type controls. Values in D are mean ± standard deviation. In vivo, RIAM deficiency neither interfered with (E) normal hemostasis as assessed by a tail bleeding time assay nor with (F-G) arterial thrombus formation upon FeCl3-induced damage of the endothelium. Each symbol in E represents 1 individual. Each symbol in F represents 1 mesenteric arteriole. Horizontal lines in E and F represent mean. Arterioles in G were visualized with an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope and a 10×/0.25 objective (Zeiss). The presented results are representative of ≥3 independent experiments with at least n = 3 vs 3 individuals per group.

RIAM deficiency does not affect platelet outside-in signaling and in vivo thrombus formation. RIAM-null platelets display a normal (A) spreading and (B) reorganization of the actin (red, Phalloidin Atto647N) and tubulin (green, α-tubulin-Alexa F488) cytoskeleton on a fibrinogen-coated (100 μg mL−1) surface. Values in A represent mean. Images in B were acquired with a TCS SP5 confocal microscope (100×/1.4 oil STED objective; Leica Microsystems). Scale bars represent 3 µm. (C-D) Platelet clot retraction of RIAM-null platelets was indistinguishable from wild-type controls. Values in D are mean ± standard deviation. In vivo, RIAM deficiency neither interfered with (E) normal hemostasis as assessed by a tail bleeding time assay nor with (F-G) arterial thrombus formation upon FeCl3-induced damage of the endothelium. Each symbol in E represents 1 individual. Each symbol in F represents 1 mesenteric arteriole. Horizontal lines in E and F represent mean. Arterioles in G were visualized with an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope and a 10×/0.25 objective (Zeiss). The presented results are representative of ≥3 independent experiments with at least n = 3 vs 3 individuals per group.

Normal hemostasis and arterial thrombus formation in RIAM-null mice

To investigate the role of RIAM in platelet integrin function in vivo, we used a tail bleeding time assay and found comparable bleeding times for control (7.2 ± 1.9 minutes) and RIAM-null mice (6.8 ± 2.1 minutes) (Figure 2E). Consistently, pathological thrombus formation, as assessed by intravital microscopy of FeCl3-injured mesenteric arterioles, was indistinguishable between control and RIAM-null mice, resulting in similar occlusion times (16.4 ± 3.8 vs 15.3 ± 4.9 minutes, respectively) for both groups (Figure 2F-G).

Our results show that RIAM is dispensable for integrin inside-out and outside-in signaling in platelets and consequently for hemostasis and arterial thrombosis in mice. Other Mig-10/RIAM/lamellipodin family members might compensate for RIAM function; however, we and others12 were unable to detect lamellipodin expression in platelets, and Mig-10 is only found in Caenorhabditis elegans.11,14 In contrast to results obtained in cell culture approaches,9-11 talin-1 was normally recruited to β3-integrins in spread RIAM-null platelets (supplemental Figure 2). Consequently, talin-1 might be recruited to integrins via alternative pathways, eg, by interaction with the exocyst complex, or by binding to the focal adhesion kinase.24,25 In support of this, Han and colleagues showed in CHO cells that talin-1 alone was sufficient to mediate β1- and β3-integrin activation, whereas RIAM and other Rap1 effectors were not.9 Moreover, because platelets lacking Rap1b or CalDAG-GEFI did not show a complete block of αIIbβ3-integrin activation, alternative mechanisms for platelet integrin activation beyond RIAM-mediated recruitment of talin-1 must be postulated.12,21

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB688 to B.N.). S.S. was supported by a grant of the German Excellence Initiative to the Graduate School of Life Sciences, University of Würzburg. The mouse strain used for this research project was created from ES cell clone 16066A-D5 obtained from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR)-National Institutes of Health-supported KOMP Repository (www.komp.org) and generated by the CHORI/Sanger/UC Davis (CSD) consortium for the NIH-funded Knockout Mouse Project.

Authorship

Contribution: S.S. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; K.W., V.L., T.V., S.G., and M.R.B. performed experiments and analyzed data; and B.N. supervised research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bernhard Nieswandt, University Hospital and Rudolf Virchow Center for Experimental Biomedicine, University of Würzburg, Josef-Schneider-Strasse 2, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; e-mail: bernhard.nieswandt@virchow.uni-wuerzburg.de.