In this issue of Blood, Mankelow et al link phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in sickle erythrocytes to a physiological event in reticulocyte maturation.1 This discovery has implications for efforts to prevent thrombosis in sickle cell disease (SCD).

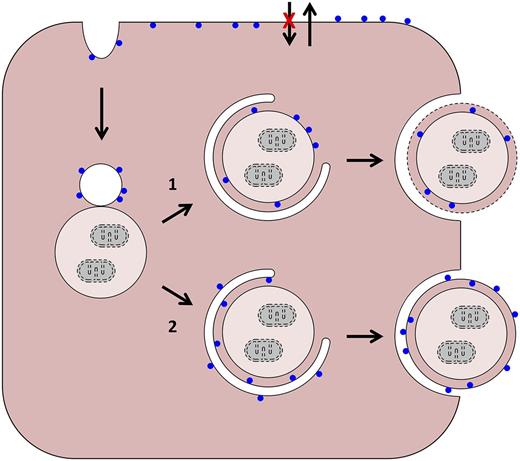

Possible pathways of PS exposure in red blood cells (RBCs). PS is represented by blue circles. Starting from the upper left, in normal and sickle reticulocytes, plasma membrane internalization creates inside-out endocytic vesicles. These can merge with autophagic vacuoles in 2 ways: (1) their membranes can fuse to create a hybrid vacuole. Egress of this structure intact from the cell would require an autophagy-like event (as depicted) or a novel process. In the former case, breakdown of the limiting membrane (dashed line) would expose PS; and (2) alternatively, the plasma membrane-derived vesicle could provide a source of isolation membrane and merge (but not fuse) with the autophagic vacuole. In this case, loss of membrane asymmetry would be required for PS exposure. As applies to older cells, and shown at the top, sickling-dependent processes lead to changes in aminophospholipid translocase and phospholipid scramblase activities, and PS exposure diffusely in the plasma membrane.

Possible pathways of PS exposure in red blood cells (RBCs). PS is represented by blue circles. Starting from the upper left, in normal and sickle reticulocytes, plasma membrane internalization creates inside-out endocytic vesicles. These can merge with autophagic vacuoles in 2 ways: (1) their membranes can fuse to create a hybrid vacuole. Egress of this structure intact from the cell would require an autophagy-like event (as depicted) or a novel process. In the former case, breakdown of the limiting membrane (dashed line) would expose PS; and (2) alternatively, the plasma membrane-derived vesicle could provide a source of isolation membrane and merge (but not fuse) with the autophagic vacuole. In this case, loss of membrane asymmetry would be required for PS exposure. As applies to older cells, and shown at the top, sickling-dependent processes lead to changes in aminophospholipid translocase and phospholipid scramblase activities, and PS exposure diffusely in the plasma membrane.

Reticulocyte maturation from enucleation to the disappearance of reticulin is a time of active cellular remodeling. During a brief developmental window, divided into R1 (first) and R2 (second) stages, reticulocytes downregulate a subset of plasma membrane proteins, shed plasma membrane, reduce their volume, and eliminate their mitochondria, ribosomes, and internal membranes.2 The end result is an erythrocyte: a cell that is flexible but durable, devoid of internal structure, and optimized for months of gas transport within the circulation.

In general, little is known about mechanisms of cellular remodeling in differentiation; in this regard, reticulocytes are a useful physiological model. For example, reticulocytes have been used to show that mitochondria are eliminated through an autophagy-related process.3 Employing an in vitro model of human reticulocyte development, Mankelow et al in the Anstee laboratory have provided insight into the mechanism of plasma membrane reduction. Earlier studies of Griffiths et al showed that glycophorin A (GPA)-containing vesicles are internalized at the R2 stage of development and merge with autophagic vacuoles (see figure)4 ; plasma membrane loss coincides with exocytosis of these hybrid vacuoles. Erythrocytes of hypercholesterolemic mice contain large autophagic inclusions, which also supports this model.5 Based on these studies, it is probable that hybrid endocytic-autophagic vacuoles are formed and eliminated during normal reticulocyte maturation, and that elimination of these structures plays a role in plasma membrane reduction.

In the earlier study by Griffiths et al, it was suggested that fusion of a vacuole with the plasma membrane leads to exocytosis of the vacuole contents, budding of the plasma membrane, and membrane loss.4 This model predicts retention of the normal membrane orientation and deposition of the vacuolar contents in the extracellular space. However, elegant immunofluorescence experiments by Mankelow et al show that intracellular epitopes of the anion exchanger 1 and GPA are expressed on the external face of the vesicle, together with the inner leaflet lipid PS, and the vacuolar contents are inside. Loss of membrane asymmetry in the vesicle prior to or during fusion with the plasma membrane or vacuole could partially explain these findings. A similar mechanism has been proposed for PS exposure in apoptotic cells.6 Another possibility is the involvement of an autophagy-like step leading to topological inversion upon fusion with the plasma membrane. Other, more esoteric, explanations are possible, and the precise mechanism of vesicle elimination from reticulocytes remains to be resolved.

Regardless of the mode of elimination, the study by Mankelow et al raises questions about the fate of the inside-out vesicles. Elimination of the vesicles occurs at the R2 stage; in vivo this would be predicted to occur in the circulation, possibly in the spleen due to macrophages with PS receptors. It has long been known that sickle erythrocytes externalize PS,7,8 and there is evidence that PS exposure plays a role in thrombosis via enhanced interactions with receptors on other circulating cells. Notably, in the current study, PS-positive cells sorted from the circulation display PS-positive surface foci, rather than a homogeneous surface of PS that has been shown previously with drug-treated RBCs.8 The authors attribute the presence of these cells in the blood of SCD patients to hyposplenism, which could reflect a desensitization of macrophages. Consistent with this interpretation, splenectomies of patients with immune thrombocytopenia leads to an increased number of circulating cells with associated PS-positive vesicles.

PS exposure in sickle red cells correlates with age and dehydration, and inversely correlates with fetal hemoglobin content; thus, sickling is implicated in the process.9 However, PS exposure is increased in both the low-density fractions and the high-density fractions, with the former enriched in reticulocytes.9,10 The current study should direct some attention to the role of reticulocytes in thrombosis, while also raising basic questions such as why the PS foci do not re-enter the plasma membrane and become more homogeneous.

A link between PS exposure and reticulocyte maturation has important implications. First, if most vesicles are released cell autonomously, as the authors’ in vitro studies suggest, and the spleen participates in the clearance of PS-positive vesicles after their release, then the prothrombotic effects of extruded vesicles may be greater than predicted based on the percentage of PS-positive erythrocytes alone. Further evidence and characterization of such free vesicles in vitro and in vivo is now crucial. Second, if it is determined that PS-positive vesicles, in isolation or tethered to erythrocytes, contribute to thrombosis in SCD, then strategies aimed at removing these vesicles or cells from the circulation could be therapeutically useful. Some of the uniquely exposed inside-out epitopes might, for example, provide a means to overcome the desensitization of hyposplenism; the “don't eat me” signal conferred by CD47 should be inside-out and make targeted clearance effective for nano-vesicles.11 The study of developmental processes can thus improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and also suggest novel therapeutic strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.