In this issue of Blood, Warkentin et al describe a novel clinical syndrome of warfarin-associated severe venous limb ischemia occurring in a series of 10 patients with malignancy after initiating treatment of deep venous thrombosis. Patients in this series also demonstrated a decline in platelet counts after stopping heparin, warfarin-associated supratherapeutic international normalized ratios (INRs), and evidence of persistent thrombin generation despite anticoagulation.1

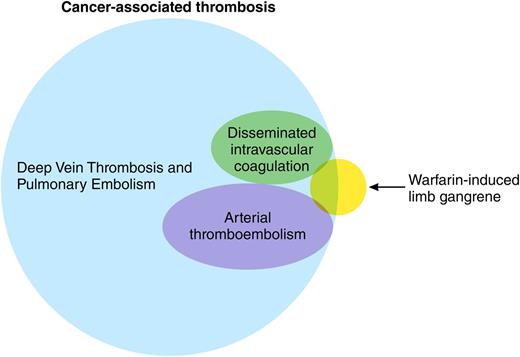

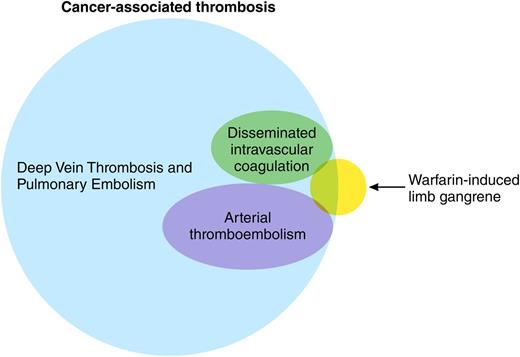

The hypercoagulable state of malignancy has been documented for more than a century, yet it seems we continue to find new manifestations. Indeed, omnicoagulable may be a better term for a clinical state that involves both the venous and arterial vasculature in nearly every part of the human body, from the well-known saddle pulmonary embolus to distal calf vein thrombi, from cerebral sinus thrombosis in children with acute leukemias to incidentally discovered portal and superior mesenteric vein thrombi in adults with pancreatic cancers, and from strokes to peripheral arterial emboli2-4 (see figure). To this lengthy list, the authors suggest a new syndrome be added.

The complications associated with warfarin therapy have also been known for a long time. Although warfarin is most notoriously associated with skin necrosis, the occurrence of venous limb gangrene has been reported previously both in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and in patients with malignancy.5 The current report, however, provides a much larger case series than previously published, created in part by a comprehensive retrospective analysis of the records of 2 hospitals over a 10-year period. The initial database accessed by the investigators included patients who tested negative for heparin-platelet factor 4 antibodies, cross-referenced against diagnoses of malignancy. The authors then undertook an exhaustive chart review and additional comprehensive hemostatic testing in available plasma specimens, the latter a particular strength of this report. Taken together, the clinical picture and testing provide a narrative of a disturbed procoagulant-anticoagulant balance leading to venous gangrene, a condition not altogether dissimilar from the pathogenesis of HIT-associated gangrene that the authors have previously reported. It is noteworthy that all patients with histologic evidence of malignancy had adenocarcinoma, which may be of particular relevance to the pathophysiology of the hypercoagulable state of malignancy.6

The process by which patients were identified, however, creates inherent weaknesses in this descriptive series: if only those patients who are being worked up for HIT (the entry point for study inclusion) are sought out, then necessarily the “syndrome” will include only those patients with an “HIT-like” presentation. This process would exclude patients, for instance, with venous gangrene but without thrombocytopenia. Further, because only patients with malignancy were included, it is unclear whether a similar picture exists in patients without malignancy, as has been reported, for example, with warfarin-induced skin necrosis. The series could be further confounded by the presence of patients with false-negative results for HIT or by patients with malignancy-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Regardless of whether this is truly a clinically distinct syndrome or not, the lethal complication of warfarin-associated venous gangrene is a grave complication of which clinicians should be aware. This report provides yet another argument against the use of warfarin for treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis (defensible in this series because many patients were only subsequently diagnosed with malignancy). Unfortunately, warfarin remains commonly used more than a decade after a seminal randomized study demonstrated its inferiority to low-molecular-weight heparins.7 Of course, clinicians should always be aware of the highly consequential albeit simpler diagnoses of pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis that complicate the lives of tens of thousands of cancer patients worldwide. Much work remains to be done to better prevent and treat the myriad manifestations of cancer-associated thrombosis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.A.K. has received research funding and consulting honoraria from Janssen, Genentech, Sanofi, and Leo Pharma.