Key Points

EBV+ LBCLs in young patients resemble those seen in the elderly, but usually have a good outcome.

Tumor cells exhibit PD-L1 expression, with high indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase–positive cell content, indications of a tolerogenic immune state.

Abstract

Few studies have reported Epstein-Barr virus–positive (EBV+) large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs) in young patients without immunodeficiency. We identified 46 such cases in patients ≤45 years of age and analyzed the clinical and pathological characteristics. EBV+ LBCLs affected predominantly males (male:female = 3.6:1), with a median age of 23 years (range, 4-45 years). All patients presented with lymphadenopathy and 11% also had extranodal disease. Morphologically, 3 patterns were identified: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma-like (n = 36), gray zone lymphoma (n = 7), and diffuse LBCL-not otherwise specified (n = 3). Tumor cells (EBV+ in >90% of cells) expressed B-cell antigens, were often CD30 and PD-L1 positive, and showed a nongerminal center immunophenotype. A total of 93% expressed EBV latency type II and 7% latency type III. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase was expressed on background accessory cells. The most common treatment regimen was rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (58%), with local radiation therapy added in 21%. With a median follow-up of 22 months, 82% of patients are in clinical remission and only 8% died of disease. Younger patients achieved a significantly higher overall survival than prior series of EBV+ LBCLs reported in the elderly (P < .0001). In conclusion, EBV+ LBCLs are not restricted to the elderly. Young patients present with nodal disease and have a good prognosis.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus–positive (EBV+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly (DLBCL-E), first described by Oyama et al,1,2 is a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid neoplasms,3 accounting for 3% to 14% of DLBCL cases.2,4-10 It is defined as an aggressive EBV+ monoclonal B-cell proliferation arising in patients >50 years of age in the absence of recognized immunodeficiency or iatrogenic immunosuppression.3 Most cases have an activated/nongerminal center B-cell immunophenotype (ABC/non-GCB).4,6,7,9-11 Senescence of the immune system inherent to the aging process leading to defective surveillance of EBV is thought to play a major role in pathogenesis.12-14 Most cases of DLBCL-E show activation of nuclear factor-κB pathway,11,15-17 most likely promoted by EBV through latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1)18,19 and less likely by MYD88, CD79B, and CARD11 gene mutations.20 Furthermore, gene expression profiling shows an enrichment of Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription–related genes(JAK/STAT), immune/inflammatory-related genes, and genes involved in cell-cycle progression and cellular metabolism.15,16 Recent studies using high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization reported cytogenetic abnormalities shared among DLBCL-E, plasmablastic lymphoma, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders and EBV-negative DLBCL-not otherwise specified (DLBCL-NOS).20

Lack of uniform criteria (eg, age cutoff, percentage of EBV+ tumor cells required for diagnosis, morphologic heterogeneity) may account for reported differences in disease prevalence and prognostic features.16,17,21 Few studies have identified EBV+ LBCLs in pediatric and young patients without known immunodeficiency.5,21-26 The reported cases showed more frequent type III EBV latency and aggressive clinical behavior,22-24 but the small number of cases analyzed and the inclusion of cases with a relatively low percentage of EBV+ cells limits firm conclusions regarding this disease in young patients.

We describe 46 cases of EBV+ large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs) in patients younger than 45 years of age with no significant prior history or identifiable causes of immunosuppression. We report that EBV+ LBCLs in younger patients resembles EBV+ DLBCL-E in many respects. They show an ABC/non-GCB immunophenotype and have EBV latency type II. In contrast to EBV+ DLBCL-E, most of these patients respond to standard treatment and have a favorable outcome.

Material and methods

Case selection

The pathology database of the Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, was searched for EBV-associated B-cell lymphomas in patients younger than 45 years of age. Forty-six cases identified were submitted in consultation over a 15-year period (1999-2014). Nearly all patients were residing in North America at the time of diagnosis, although 2 patients were referred from South America, 2 from the United Kingdom, and 1 from Asia. Patients with impairment of the immune system secondary to primary immunodeficiency, HIV infection, transplantation, autoimmune disease, previous solid cancer, or lymphoma were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were evidence of acute or recent EBV infection and a specific lymphoma subtype known to be associated with EBV (such as Burkitt lymphoma, classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), lymphomatoid granulomatosis, primary effusion lymphoma and plasmablastic lymphoma). Also, only cases in which all or almost all tumor cells (>90%) were EBV+, either by EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER), LMP1, or EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2), were included. The following clinical and laboratory data were collected: disease location at presentation, presence/absence of B symptoms, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), peripheral blood counts, EBV serology, clinical stage, flow cytometry studies, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for immunoglobulin rearrangements, primary treatment instituted (type and starting date), relapse, secondary treatment, current status, and date of last follow-up. All cases were reviewed by 3 of the authors (E.S.J., S.P., and A.N.) and a consensus was reached in terms of morphological subtypes.

Clinical and morphological features were compared with a previously reported series of EBV+ LBCLs from our group.27 For the cases reported by Dojcinov et al,27 only cases with outcome data were included (n = 25); cases diagnosed as EBV-associated reactive hyperplasia, mucocutaneous ulcer, and plasmablastic lymphoma were excluded. In the course of our review, we observed that many of the cases shared features with T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL). Therefore, a prior study of THRLBCL (n = 40)28 was used for a comparison of clinical parameters. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization studies

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization (ISH) studies were performed on available formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections according to previously published techniques.27 The antibody panel included CD20, CD3, CD15, CD30, CD79a, PAX5, Oct-2, Bob.1, Bcl-6, CD10, multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM1), Bcl-2, epithelial membrane antigen, immunoglobulin D (IgD), CD21, PD-1/CD279, PD-L1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), LMP1, EBNA2, and EBV immediate early protein. The panel of antibodies, clone, dilution, and source are listed in supplemental Table 1 available on the Blood Web site.

All cases were tested for EBER by ISH. The EBER1 DNP probe supplied by Ventana on an automated stainer (Ventana-Benchmark XT, Tucson, AZ) was used.27

PCR for immunoglobulin gene rearrangements

DNA was extracted from whole tissue formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections and amplified by PCR for detection of Ig (Ig heavy [IGH@] and Ig kappa locus [IGK@]) gene rearrangements, as published previously.27 For the IGH locus, we employed consensus primers directed against the joining region with forward primers for the VH framework III and VH framework-II; for the IGK analysis, the primer sets interrogated rearrangements involving the Vκ loci and Jκ (tube A), the Vκ locus and the κDE locus (tube B), and the κ-intron RSS locus and the κDE locus (tube B) (Invivoscribe Technologies, Inc, San Diego, CA).

Cases were considered clonal if at least 1 significant peak (≥2.5 × the height of the tallest neighboring peak) was detected in 1 of the 2 IGH reactions or if 2 peaks (within the valid range determined by Invivoscribe) were detected in 1 or both IGK reactions when no heavy chain rearrangement was detected. Cases were considered indeterminate for clonality if a peak was detected in the IGH reaction that did not meet the height criterion for a significant peak or if only 1 light chain peak was detected in the absence of IGH peaks.

Statistical methods

Overall survival (OS) was defined from date of diagnosis until date of death or last follow-up. Survival distributions were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and the significance of difference between pairs was determined by the log-rank test. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Comparisons of clinical and laboratory characteristics between EBV+ LBCLs with THRLBCL-like morphology vs THRLBCL reported by Achten et al28 were performed with Fisher’s exact test. All P values are 2-tailed and presented without any adjustment for multiple comparisons. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

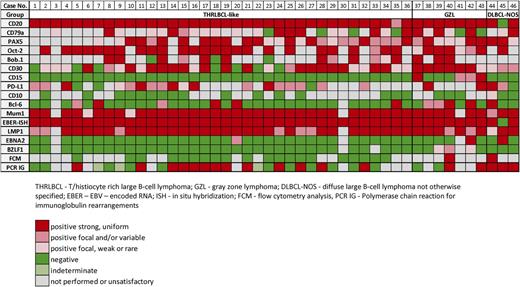

Morphology and immunophenotype

Three main histological patterns were identified based on the cytological features and density of tumor cells and associated inflammatory microenvironment. These included: THRLBCL-like (n = 36), B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and CHL—the so-called gray zone lymphoma (GZL) (n = 7) and DLBCL-NOS (n = 3). None of the 46 cases displayed a spectrum in B-cell maturation with plasmacytoid differentiation that is characteristic of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders.

EBV+ THRLBCL-like (36 cases, 78%)

These cases had a minor component of EBV+ large cells embedded in a rich inflammatory background composed mainly of histiocytes and small lymphocytes (Figure 1). The lymph nodes showed total or subtotal effacement of the architecture with remnants of residual follicles present in 24/34 (71%) cases. Capsular fibrosis and/or partial fibrous septa were seen in half of cases. The neoplastic B cells were cytologically diverse and included cells that resembled Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS), lymphocyte-predominant cells, admixed with round to oval forms resembling centroblasts or immunoblasts. The neoplastic cells were scattered either singly or in loose clusters in 28/36 (78%) of cases and in 22% formed focal sheets. Besides histiocytes and small lymphocytes, the inflammatory background contained scattered plasma cells (n = 13) and/or eosinophils (n = 5); well-formed granulomas were rarely seen (n = 2). Mummified/individual necrotic cells were frequently observed (27/36, 75%); 8 cases (22%) showed foci of necrosis and a single case had extensive areas of necrosis.

THRLBCL-like cases (case 13 [A-C,G,H,J-L], case 11 [D-F], and case 16 [I]). (A) The lymph node shows effacement of the architecture. (B) Scattered mono- or multilobated tumor cells, some HRS-like, are observed in a lymphohistiocytic microenvironment. (C) Bone marrow biopsy shows similar morphology. (D) Case 11 shows a diffuse proliferation, rich in histiocytes with sparse tumor cells, morphologically indistinguishable from THRLBCL. (E) Foci of necrosis are present. (F) The tumor cells are positive for CD20, with rare small B cells in the background. Most cases expressed CD79a (G), CD30 (H), PD-L1 (I), LMP1 (J), and EBER (K). (L) Numerous dendritic cells/histiocytes IDO positive are present in the microenvironment. Original magnifications: ×40 (A), ×100 (E), ×200 (D,F), and ×400 (B,C,D inset, G-L).

THRLBCL-like cases (case 13 [A-C,G,H,J-L], case 11 [D-F], and case 16 [I]). (A) The lymph node shows effacement of the architecture. (B) Scattered mono- or multilobated tumor cells, some HRS-like, are observed in a lymphohistiocytic microenvironment. (C) Bone marrow biopsy shows similar morphology. (D) Case 11 shows a diffuse proliferation, rich in histiocytes with sparse tumor cells, morphologically indistinguishable from THRLBCL. (E) Foci of necrosis are present. (F) The tumor cells are positive for CD20, with rare small B cells in the background. Most cases expressed CD79a (G), CD30 (H), PD-L1 (I), LMP1 (J), and EBER (K). (L) Numerous dendritic cells/histiocytes IDO positive are present in the microenvironment. Original magnifications: ×40 (A), ×100 (E), ×200 (D,F), and ×400 (B,C,D inset, G-L).

Immunophenotypically (Table 1), the tumor cells had an intact B-cell phenotype with coexpression of CD20, CD79a, PAX5, Bob.1, and Oct-2. Most cases were CD30+ (29/36) and none expressed CD15 (0/36). All 34 analyzed cases expressed MUM1 and, although 6/34 showed positivity for Bcl-6, none expressed CD10 (0/16), indicative of a non-GCB immunophenotype. Sixteen of 21 (76%) cases were positive for PD-L1 in >5% of tumor cells; frequently, the cells were heterogeneously stained. PD-L1 expression on tumor cells did not correlate with the number of PD1+-reactive T cells. Seven of 13 cases had Bcl-2 expression; 2/15 showed focal, weak expression of IgD; and none of 13 analyzed cases was epithelial membrane antigen–positive. CD21 revealed focal disrupted residual follicular dendritic cell meshworks in 23/31 cases, and IgD highlighted disorganized/expanded mantles in 7/15. Other than the disrupted follicles, normal-appearing B cells were generally few in number. All cases showed an inflammatory background rich in small reactive CD3+ T cells, with rosettes around the tumor cells in one-third of cases; 9/34 cases had frequent PD1+ T cells. Most cases (20/23, 87%) showed high expression of IDO restricted to dendritic cells/histiocytes and endothelial cells. Additionally, the tumor-associated histiocytes were moderately or strongly positive for PD-L1 (20/21, 95%).

EBV+ GZL (7 cases, 15%)

All of these cases had some features reminiscent of CHL-nodular sclerosis grade 2, but with strong expression of the B-cell program (Figure 2). They contained clusters and sheets of large cells resembling HRS cells and variants, admixed with small lymphocytes, eosinophils, granulocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Two of the 7 had more monomorphic areas with a cohesive pattern of growth. Areas of sclerosis were consistently present. Necrosis was seen in all and was extensive in 4. Tumor cells were strongly and uniformly positive for CD20 in all; they were also positive for CD79a, PAX5, Oct-2, Bob.1, Bcl-6, and MUM1. All showed expression of CD30, 4 expressed CD15, and 2 cases were positive for PD-L1.

GZL (case 43). (A) The lymph node architecture is altered by nodular proliferation divided by collagen bands. (B) Sheets of large cells resembling HRS cells and variants—admixed with small lymphocytes, eosinophils, and granulocytes—are identified. (C) Foci of necrosis are present. The tumor cells are strongly and uniformly positive for CD20 (D), PAX5 (E), and Oct-2 (F). They are also positive for CD30 (G), CD15 (H), LMP1 (I), and EBER (J). Original magnifications: ×40 (A); ×200 (C), and ×400 (B,D-J).

GZL (case 43). (A) The lymph node architecture is altered by nodular proliferation divided by collagen bands. (B) Sheets of large cells resembling HRS cells and variants—admixed with small lymphocytes, eosinophils, and granulocytes—are identified. (C) Foci of necrosis are present. The tumor cells are strongly and uniformly positive for CD20 (D), PAX5 (E), and Oct-2 (F). They are also positive for CD30 (G), CD15 (H), LMP1 (I), and EBER (J). Original magnifications: ×40 (A); ×200 (C), and ×400 (B,D-J).

EBV+ DLBCL-NOS (3 cases, 6.5%)

In 3 cases, the features were those of DLBCL-NOS, with sheets of tumor cells (Figure 3). Two cases were relatively monomorphic, composed of medium to large lymphoid cells, whereas the third case showed more pleomorphism with extensive intrasinusoidal involvement. Two cases were strongly CD20+, whereas the third case was positive for CD79a, PAX5, and Oct-2 in the absence of CD20. The tumor cells were positive for MUM1 and CD30 and were negative for CD15. Two cases were PD-L1+ and only 1 case expressed Bcl-6 and CD10.

DLBCL-NOS (case 45). (A) Diffuse lymphoid proliferation of medium to large cells that dissects the skeletal muscle of chest wall. (B) Mitotic figures were readily seen. The tumor cells are positive for CD79a focal (C), PAX5 strong (D), MUM1 (E), LMP1 (F), and EBNA2 (G). This was 1 of 3 cases that expressed a latency III phenotype. Original magnifications: ×200 (A) and ×400 (B-G).

DLBCL-NOS (case 45). (A) Diffuse lymphoid proliferation of medium to large cells that dissects the skeletal muscle of chest wall. (B) Mitotic figures were readily seen. The tumor cells are positive for CD79a focal (C), PAX5 strong (D), MUM1 (E), LMP1 (F), and EBNA2 (G). This was 1 of 3 cases that expressed a latency III phenotype. Original magnifications: ×200 (A) and ×400 (B-G).

EBV serology data, in situ hybridization for EBER, and EBV latency

EBV serologic data were available in 17 patients. All showed evidence of past infection: 17/17 were EBV-viral capsid antigen IgG-positive and EBV-viral capsid antigen IgM-negative; 13/13 were also EBNA-1 IgG-positive. For 5/8 patients, EBV-early antigen IgG was positive, as an indicator of virus reactivation.

EBER-ISH was positive in all but 1 case (45/46) (1 DLBCL-NOS) in >90% of the viable atypical cells. In 58% of cases, EBER positivity was confined to large cells, whereas the remainder showed some spectrum in cell size. LMP1 was present in all 43 analyzed cases, including the 1 EBER-negative case. In approximately two-thirds of cases (72%), LMP1 was strongly and uniformly positive in all tumor cells. EBNA2 was negative in 40/43 (93%) cases, consistent with EBV latency type II, and 3 cases (7%) (1 in each morphologic subgroup) were EBNA2-positive, suggesting an EBV latency type III. Only 3/42 cases (7%), all GZL, had rare cells positive for EBV immediate early protein, suggesting a possible lytic component.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis performed in outside institutions was available in 22 cases; only 2 cases (1 GZL, 1 DLBCL-NOS) showed light chain restriction. In tumors with necrosis and a high content of reactive cells, flow cytometry studies have a low positive yield.

PCR for IG gene rearrangements

PCR results were obtained in 34/40 (85%) of cases. A monoclonal IG rearrangement was seen in 53% of cases; an additional 3 cases (9%) were indeterminate, having a single peak with only the light chain probes. Four cases (12%) were polyclonal; the remaining 9 cases (26%) lacked a clonal peak, but amplification failed with 1 or more of the reactions.

Clinical features and course

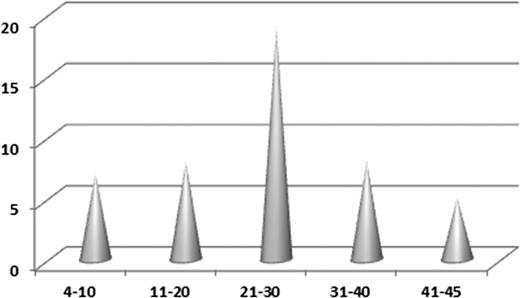

The study cohort included 46 patients: 36 males and 10 females (male:female ratio = 3.6:1), with a median age of 23 years (range, 4-45 years). The age distribution followed a Gaussian curve with a peak in the third decade of life (n = 19) (Figure 4). Two patients were pregnant. Treatment and follow-up information was obtained for 39 patients (85%). The clinical data are summarized in Table 2.

Distribution of EBV+ LBCLs per age group. The age distribution followed a Gaussian curve, with a peak in the third decade of life (n = 19).

Distribution of EBV+ LBCLs per age group. The age distribution followed a Gaussian curve, with a peak in the third decade of life (n = 19).

All patients presented with lymphadenopathy that was either localized (≤2) (n = 23) or with multiple sites/generalized (>2) (n = 22). The most common sites of lymph node biopsy were cervical (n = 15), axillary (n = 9), and supraclavicular (n = 4). Mediastinal disease was present in 12 patients (27%), 5 of which had GZL morphology. Nonlymphoid organ involvement was observed in 5 patients (11%) and included bone (n = 4), liver (n = 3), and lung (n = 1). Clinically, 29% of patients (13/45) presented with splenomegaly, all from the THRLBCL–like subgroup; 52% had B symptoms, 67% had elevated LDH, 45% had abnormal complete blood cell (CBC) counts (mainly cytopenias), and 9/37 (24%) had bone marrow involvement. The clinical stage was known for 36 cases; 3 were stage I, 13 stage II, 10 stage III, and 10 stage IV. Therefore, 56% of patients presented with advanced stage disease and 37% had an International Prognostic Index (IPI) score >2.

All patients but 2 were treated with chemotherapy ± rituximab. One patient received rituximab only. The most common regimen used was rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (22/38, 58%). For 8 patients (21%), local radiation therapy was added. Three patients underwent high-dose carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT) and 2 received allogeneic BMT, in 1 instance for therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia, t(9,11) positive, that developed 11 months after initial chemotherapy. Three patients relapsed at 14, 18, and 21 months and all achieved a second complete remission. Three patients died of disease at 13, 17, and 20 months. Overall, with a median follow-up of 22 months (range 4-96 months), 82% patients were alive with no evidence of disease, 10% were alive with disease, and 8% died of disease.

Associations between morphologic subgroups and clinical parameters

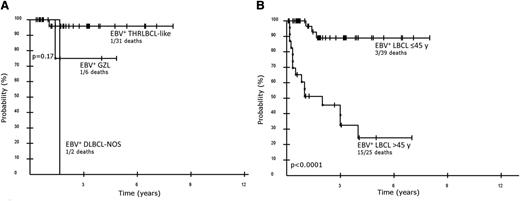

A comparison of outcome between the morphological subgroups of EBV+ LBCLs in young patients was performed. Because there were only 2 patients with outcome data in the DLBCL-NOS group, this group will not be discussed. Median OS was not reached for the entire cohort, nor for THRLBCL-like or GZL. No major differences in survival were observed between THRLBCL-like and GZL, with 3-year OS of 95.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 79.8-99.3) vs 75.0% (95% CI, 30.1-95.4) (P = .17) (Figure 5A). The outcome of all EBV+ LBCLs in young patients was compared with a published series of EBV+ DLBCL in elderly patients (>45 years of age).27 Younger patients achieved a significantly higher OS than the elderly patients, with a 5-year OS probability of 89.0% (95% CI, 72.1-96.2) vs 24.4% (95% CI- 9.7-49.1) (P < .0001), whereas the median OS for the elderly was 2 years (Figure 5B).

Kaplan-Meier curves of EBV+ LBLCs in young patients. (A) Overall survival of morphological subgroups of EBV+ LBCLs in young patients (≤45 years); overall survival THRLBCL-like vs GZL at 3 years is 95.8% and 75%, respectively (P = .17). (B) Overall survival of EBV+ LBCL in young patients, all groups, regardless of morphological pattern and EBV+ DLBCL in elderly patients (>45 years of age) including all causes of death, is 89.0% and 24.4% at 5 years, respectively (P < .0001).

Kaplan-Meier curves of EBV+ LBLCs in young patients. (A) Overall survival of morphological subgroups of EBV+ LBCLs in young patients (≤45 years); overall survival THRLBCL-like vs GZL at 3 years is 95.8% and 75%, respectively (P = .17). (B) Overall survival of EBV+ LBCL in young patients, all groups, regardless of morphological pattern and EBV+ DLBCL in elderly patients (>45 years of age) including all causes of death, is 89.0% and 24.4% at 5 years, respectively (P < .0001).

Interestingly, there were no significant clinical differences between EBV+ LBCLs with THRLBCL-like morphology and a previously published THRLBCL cohort28 in terms of gender (both with a male predominance), LDH, presence of splenomegaly and bone marrow involvement, clinical stage, and IPI score (Table 3). Patients with EBV+ THRLBCL-like lymphoma showed a significantly better 5-year OS than the historical THRLBCL series. However, 30/38 (79%) of patients in the current study received chemotherapy with the addition of rituximab.

Discussion

EBV+ DLBCL-E was included in the 2008 WHO classification as a provisional entity and was postulated to be a result of defective immune surveillance for EBV as a result of aging.1-6,11,27,29 Most studies have concluded that DLBCL-E is associated with an aggressive clinical course,2,7,10,11,27,29 although variations in the criteria applied to consider a case EBV+ make comparison among series difficult. Since then, a handful of studies have reported EBV+ DLBCL in young patients, with contradictory conclusions regarding the significance of EBV on clinical outcome.22-26 However, again lack of consensus and small numbers of cases analyzed preclude firm conclusions.

In this study, we present the clinicopathologic features of 46 cases of EBV+ LBCLs in patients younger than 45 years of age and compare the outcome with reported series of EBV+ DLBCL-E.27 We chose age 45 as an age cutoff to avoid overlap with EBV+ DLBCL-E. Two main inclusion criteria were used: lack of a history of immunodeficiency or immune compromise and evidence of EBV infection in >90% of the tumor cells. Twelve patients were in the pediatric age group, and although we could not completely rule out an underlying immunodeficiency, only 2 expressed latency type III, which is more often associated with immune compromise.18,19,30 We required that 90% of viable tumor cells show evidence of EBV to avoid the inclusion of cases in which EBV may be a bystander in nonneoplastic cells. Some studies have used lower thresholds as low as 20%7,8,21,24,25 or even 10%5,9,11,16 to define EBV+ DLBCL, and it is questionable whether in such cases the virus represents a true pathogenic event.6

We observed similarities and differences with EBV+ DLBCL in the elderly (Table 4). The predominance of males in our series (male to female ratio of 3.6) is similar to what has been observed in the elderly.4,5,9,24 However, all patients had nodal disease, with only 11% showing extranodal involvement as well. This is in contrast with the higher incidence of extranodal disease reported in the elderly population.1,2,6,7,11,21,27

Notably, with a median follow-up of 22 months, most patients (82%) are in clinical remission and only 3 (8%) died of disease. EBV+ LBCLs in our cohort showed a significantly better OS than EBV+ LBCLs in a prior study of elderly patients (P < .0001).27 It is known that age represents an independent prognostic factor for survival in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Although multiple studies have acknowledged the aggressive clinical course of EBV+ DLBCL-E2,7,10,11,27,29 and EBV has been considered an independent adverse factor,8,31 the negative impact of EBV was restricted to patients >50 years of age and did not influence survival in young patients.8 Our results are similar to those reported recently by Hong et al25 and contrast with the poor prognosis observed by Beltran et al and Cohen et al in a limited number of patients.22,24 Seventy-nine percent of patients received rituximab in addition to chemotherapy, likely contributing to the good outcome. It has been shown that rituximab chemotherapy improved survival of patients with THRLBCL32 and EBV+ DLBCL-E7,21 and abolished the negative impact of EBV on the outcome of patients with DLBCL16 and DLBCL-E.9

EBV+ LBCLs in young patients showed dysregulation of immune checkpoints, IDO, and PD1/PD-L1 axis with promotion of an inhibitory, tolerogenic immune environment. Most of the analyzed cases independent of histological subgroup showed PD-L1 positivity in the tumor cells and high expression of PD-L1 and IDO in the histiocytic/dendritic cell microenvironment. The mechanism of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells could be either related to EBV presence and/or cytokine milieu. It has been shown that EBV-LMP1 increases PD-L1 promoter and enhancer activity33 and that PD-L1 can be induced on both tumor cells and macrophages as a response to interferon-γ, a critical antitumoral and antiviral cytokine.34 IDO is an important negative immunoregulator, which when induced by proinflammatory signals (interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6) attenuates T-cell clonal expansion, induces anergy and apoptosis of effector T-cells, and promotes T-regulatory cell differentiation.35 Therefore, it is likely that PD-L1 presence on tumor cells together with high expression of IDO and PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor immune escape. However, conflicting data have been reported regarding the prognostic impact of IDO expression in lymphomas and cancer.36,37 In this patient cohort, the expression of PD-L1 and IDO did not appear to lead to an adverse outcome.

Studies using recombinant forms of EBV have shown the absolute requirement for LMP1 in the transformation process.18,19 Approximately two-thirds of cases showed uniform LMP1 expression by almost all tumor cells. This degree of positivity contrasts with what is typically observed in CHL and other EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, in which usually only a subset of tumor cells is positive. LMP1 also plays a role in the common expression of the ABC/non-GCB phenotype and PD-L1 and CD30 positivity observed in most EBV+ lymphomas.2,4-9,11,16,38 Most of our cases expressed CD30, but the expression of this activation marker did not predict an adverse outcome in young patients, as was suggested in older patients with EBV+ DLBCL.16 LMP1 is also associated with downregulation of BCL6,39,40 a finding supported by our data.

Almost all cases tested (93%) had EBV latency II (LMP1+, EBNA2−), with only 7% showing latency III (LMP1+, EBNA2+). Cohen et al,23,24 using quantitative PCR to measure latency gene expression, found a higher incidence of latency III, but RNA levels may not correlate with actual protein expression. The low frequency of latency III in our cohort indirectly supports the immunocompetent status of our patients. EBV latency III has been linked more frequently with proliferations arising in the setting of overt immunodeficiency, such as HIV infection or solid organ transplantation.18,19,30 In fact, Hofscheier et al recommended careful evaluation for other triggers of immunosuppression besides age in patients diagnosed with EBV+ DLBCL-E and latency III.6 Only 3 of our patients had EBV latency III: 1 was pregnant at time of diagnosis and died of disease and the other 2 are alive without disease at 20 and 33 months.

The histological spectrum of EBV+ LBCLs in young patients showed some diversity, with most of the cases resembling THRLBCL with scattered large B cells in a background rich in T cells and histiocytes. The tumor cells were cytologically diverse, often mimicking HRS and lymphocyte-predominant cells. This morphological pattern has been noted in other series, referred to as Hodgkin lymphoma–like11,17 or polymorphic.1,2,6,10 Although some older series reported that a subset of THRLBCL could be positive for EBV,41,42 the WHO classification suggested that the term THRLBCL be reserved for cases lacking EBV.3 For this reason, we refer to the cases reported here as THRLBCL-like. Additionally, in contrast to THRLBCL focal residual B-cell areas were observed in most cases.

Fifteen percent of cases showed a histological pattern consistent with GZL. They involved mediastinum and/or cervical lymph nodes, as frequently seen in this entity.43,44 As with EBV− GZL, they displayed a preserved B-cell program and were often positive for CD30 and sometimes CD15 (4/7 cases).44 The WHO classification stated that GZL could be positive for EBV in a subset of cases,3 although the difficulty in distinguishing such cases from EBV+ DLBCL-E led to a recommendation for caution in making this diagnosis.45

In summary, EBV+ LBLCs are not uncommon in younger patients, and may be seen in the pediatric age group. They most often present with nodal disease. The most common histological pattern resembles THRLBCL, and we recommend that EBV studies be routinely performed in cases with these features to better assess the prevalence and clinical features in future studies. The concept of EBV+ LBCLs as a disease of the elderly requires reassessment in light of these data.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank personnel of the immunohistochemistry unit for their expert technical assistance as well as to the submitting pathologists and clinicians who provided the clinical and follow-up data to complete the study. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Kieron Dunleavy for clinical advice in improving the manuscript.

This study was supported by the intramural research program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: A.N., S.P., and E.S.J. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; S.A. and T.D.-H. performed studies for EBV and viral latency; S.M.S. provided statistical analysis; and T.A.P., L.X., and M.R. performed molecular testing and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The authors’ contribution to the work was done as part of the authors’ official duties as National Institutes of Health employees and is a work of the US government. Therefore, copyright may not be established in the United States.

Correspondence: Elaine S. Jaffe, Hematopathology Section, Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, 10 Center Dr, Building 10, MSC-1500, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: elainejaffe@nih.gov.

![Figure 1. THRLBCL-like cases (case 13 [A-C,G,H,J-L], case 11 [D-F], and case 16 [I]). (A) The lymph node shows effacement of the architecture. (B) Scattered mono- or multilobated tumor cells, some HRS-like, are observed in a lymphohistiocytic microenvironment. (C) Bone marrow biopsy shows similar morphology. (D) Case 11 shows a diffuse proliferation, rich in histiocytes with sparse tumor cells, morphologically indistinguishable from THRLBCL. (E) Foci of necrosis are present. (F) The tumor cells are positive for CD20, with rare small B cells in the background. Most cases expressed CD79a (G), CD30 (H), PD-L1 (I), LMP1 (J), and EBER (K). (L) Numerous dendritic cells/histiocytes IDO positive are present in the microenvironment. Original magnifications: ×40 (A), ×100 (E), ×200 (D,F), and ×400 (B,C,D inset, G-L).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/126/7/10.1182_blood-2015-02-630632/4/m_863f1.jpeg?Expires=1769205418&Signature=gCGxQK5LvbcNeh3J18O3U8E8~ukpdFv7A~xXh~R4JZowcWFKzxqR1LejYhE7hi~IBbldglNeL7XJXv1Br4Q0nqKyZBY7M1U5vYXJ~F49zw0M-dmLCXSGrN-ALEYuwf6627ZZV8YfXL-sDSUI4wwPxzMAUsDgP34XhwE0YDhFxubGJouAN9GOll-lAlqJD8CSs6xYdiu5Rs8Im7IpcmML29eZLKVM~csjVpElRiw8X4XXCvnYh278jRSXnsX8Es0F4u0ZeWbzJtEACkahoObA2XwHSu6P70qsw5V~k3wHUMrvoHECQlCOi-VQkWagGvYjvxXa-lSPmT9fDn4ah4eqmA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)