Abstract

Despite the success of standard front-line chemotherapy for classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), a subset of these patients, particularly those with poor prognostic factors at diagnosis (including the presence of B symptoms, bulky disease, advanced stage, or extranodal disease), relapse. For those patients who relapse following autologous stem cell transplant (SCT), multiple treatment options are available, including single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy strategies, radiotherapy, the immunoconjugate brentuximab, checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab, lenalidomide, everolimus, or observation in selected patients. In patients with an available donor, allogeneic SCT may also be considered. With numerous treatment options available, we advocate for a tailored therapeutic approach for patients with relapsed cHL guided by patient-specific characteristics including age, comorbidities, sites of disease (nodal or organ), previous chemosensitivity, and goals of treatment (long-term disease control vs allogeneic SCT).

Introduction

With chemotherapy alone or in combination with radiotherapy, 3- to 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 82% to 94.6% are observed in patients with newly diagnosed limited-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL).1-4 For advanced-stage cHL, front-line doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD), doxorubicin, vinblastine, mechlorethamine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, prednisone (Stanford V), or escalated bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone (BEACOPP) lead to 5-year PFS rates of 71% to 86.4% and freedom-from-treatment failure (FFTF) rates of 68% to 88%.5-7 Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for patients with relapsed/refractory disease after front-line chemotherapy offers PFS rates of 50% to 60% and 40% to 45% in patients with chemosensitive disease and primary refractory cHL, respectively.8-17 Nevertheless, up to 50% of the cHL patients experience disease recurrence after ASCT.18-24 Several factors associated with an increased risk of relapse following ASCT include number of prior regimens, less than a complete remission (CR) by positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) to salvage treatment prior to ASCT, duration of first remission <12 months, Karnofsky performance scale score <90, and extranodal involvement.18-21 The median overall survival (OS) of patients who relapse after ASCT was initially reported to be <1 year.22,23 More recent data suggest that the median OS may be closer to 2 years.21,24,25 The availability of novel therapies to treat cHL patients that relapse after ASCT as well as the availability of allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) for selected patients may all contribute to this improved OS.26-33

Herein, we present 3 cases to illustrate transplant options for primary refractory patients, the role of consolidation therapy post-ASCT for high-risk patients, and a patient-specific approach to relapsed/refractory cHL following previous ASCT.

Case presentation 1

A 22-year-old man was diagnosed with nonbulky stage IIA cHL involving bilateral cervical nodes and mediastinum. Staging PET/CT demonstrated a 1.9 × 2.9 cm right cervical node with standardized uptake value (SUV) 10.6, a 1.9 × 2.2 cm right paratracheal node with SUV 8.0, and a 1.3 × 1.7 cm left pectoralis node with SUV 8.6. He was treated with ABVD. PET/CT after 2 cycles demonstrated a partial response (PR) with SUV 3.6 in the right cervical node and resolution of the other nodal sites. After cycle 3, the patient palpated a new right cervical node and PET/CT after cycle 4 demonstrated an increased SUV of 10 from 3.6 in the previous right cervical node and a new right cervical node with SUV 3.3. Repeat excisional biopsy confirmed cHL. He received 2 cycles of gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and doxorubicin (GVD) and subsequent ASCT with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) conditioning. Post-ASCT, he received involved field radiation therapy (IFXRT) at 30 Gy in 17 fractions to the right cervical region followed by brentuximab vedotin.

Primary refractory cHL

Two randomized phase 3 trials and several smaller studies support the role of ASCT for relapsed/refractory cHL patients with chemosensitive disease to salvage therapy with PFS rates of 50% to 60%.8-11,14,15 Linch et al reported on 40 patients who were randomized to either BEAM plus ASCT or the same drugs at lower doses not requiring bone marrow rescue (mini-BEAM).8 Three-year event-free survival (EFS) was significantly in favor of BEAM plus ASCT (53% vs 10%, P = .005). Schmitz et al reported on 161 patients with relapsed cHL who received 2 cycles of dexamethasone-BEAM (dexa-BEAM), with responding patients randomized to either 2 additional cycles of dexa-BEAM or ASCT.9 Although there was no difference in OS, 3-year freedom-from-treatment failure (FFTF) was significantly improved in the ASCT group (55% vs 34%, P = .019).

Neither of these randomized phase 3 trials included chemorefractory patients. Although supported only by retrospective data, several studies demonstrated that chemorefractory disease can be partially overcome by high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT, resulting in PFS rates of 40% to 45%.16,17,23,34 For example, Lavoie et al reported on 100 cHL patients who underwent ASCT at first relapse (60 patients), were primary refractory (23 patients), or underwent ASCT at second relapse (17 patients).16 As expected, both PFS and OS were better in the relapsed patients compared with the other 2 groups. However, a 15-year PFS rate of 39% was reported for the refractory patients. Gerrie et al reported on 256 cHL patients who underwent ASCT with either relapse disease or with primary refractory lymphoma.17 Again, although 10-year PFS and OS rates were better for the relapsed cHL group, patients with refractory disease either chemosensitive or resistant to salvage chemotherapy had remarkable 10-year PFS rates of 47% and 31%, respectively.

Brentuximab vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin, an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody conjugated to monomethyl auristatin E, a microtubule disrupting agent, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 for relapsed cHL after ASCT or 2 prior chemotherapy regimens as the result of a pivotal phase 2 study where 102 patients were treated with 1.8 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a maximum of 16 cycles.28 The overall response rate (ORR) was 75% (34% CR). Median OS and PFS were 22.4 and 5.6 months, respectively. Grade 3-4 adverse events included neutropenia (20%), thrombocytopenia (8%), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (8%). Analysis of selected patient characteristics did not reveal any association of disease status (relapsed vs refractory), number of prior therapies, age, or disease bulk with response. Among the 34 patients who achieved CR, 47% remained disease-free at a median of 53 months, including 12 of 28 patients who did not go onto consolidative allogeneic-SCT. These long-term responders were typically younger (median age, 26 years), with relapsed (rather than refractory) early-stage disease, and a lower disease burden. Therefore, for a subset of patients achieving CR with brentuximab after previous ASCT, prolonged disease control can be maintained without additional chemotherapy or allogeneic SCT.

More recently, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase 3 study (AETHERA) evaluated brentuximab as consolidation therapy after ASCT in 329 high-risk cHL patients with primary refractory disease, disease relapse <12 months after front-line therapy, or extranodal involvement.35 Patients were randomized to brentuximab consolidation at 1.8 mg/kg every 3 weeks vs placebo for up to 16 cycles. Although no difference in OS was seen, consolidation with brentuximab resulted in significantly improved 2-year PFS compared with placebo (63% vs 51%; P = .001).

Based on the exceptionally high ORR with brentuximab in patients with relapsed or refractory cHL after ASCT, our first-line recommendation in this patient population is brentuximab. In those patients who achieve a CR with brentuximab, particularly younger patients with low-risk early-stage disease, it is reasonable to observe them without additional consolidative therapy or allogeneic SCT, in light of the recently reported long-term response data.28,36 Furthermore, for those patients with primary refractory disease, relapse within 12 months, or extranodal disease, treatment with brentuximab consolidation following ASCT should be offered starting 1 to 2 months after ASCT.

Case presentation 2

A 34-year-old woman presented with stage IIIB cHL in 1996 and was treated with mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP)/doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine (ABV) for 6 cycles, achieving CR. Six months later, the cHL recurred in the mediastinum and the patient received 2 cycles of dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP) followed by ASCT, again achieving CR. In 2000, biopsy of a left cervical lymph node confirmed recurrent cHL. The patient refuses allogeneic SCT and since 2000 she has received the following therapies:

March 2000: IFXRT to left cervical adenopathy.

April 2007: Weekly gemcitabine for 6 months for mediastinal disease.

October 2007: Etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHAP) for 6 cycles.

June 2008: IFXRT to mediastinum.

June 2009: New sternal lesion biopsied confirming cHL, observed without treatment.

February 2010: Weekly vinorelbine for 9 months.

December 2011: Brentuximab for 6 cycles.

October 2012: New left lower lobe lung lesion, retreatment with brentuximab for 7 cycles, stopped due to sensory neuropathy.

March 2013-June 2015: Persistent lung lesion, observed without treatment.

June 2015: Biopsy of enlarging lung lesion confirms cHL and leads to treatment with pembrolizumab on a clinical trial.

Treatment options for patients relapsing after ASCT

For those patients with cHL relapsing after ASCT and who have received brentuximab, there are a number of options for treatment outlined in Table 1,37-43 Table 2,44-57 and Table 328-33,58-61 . Treatment decisions should be based on the long-term goals of therapy; for example, prolonged disease control vs achievement of best response prior to allogeneic SCT, extent and location of disease, symptoms, patient comorbidities and age, and patient preference. Options include observation for asymptomatic patients with a low disease burden, IFXRT for patients with limited disease in fields amenable to radiation, single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy, checkpoint inhibitors, immunomodulatory therapy, or clinical trials with novel agents.

For patients who are not allogeneic SCT candidates, the goal of therapy is typically to control the disease as long as possible with minimal toxicity including future myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML). IFXRT may lead to prolonged remissions and delay the need for palliative chemotherapy in cHL patients who relapse after ASCT with localized disease.62-64 For patients relapsing after front-line therapy, IFXRT leads to a 5-year FFTF and OS of 28% and 51%, respectively.63 In a report by Vose et al,65 the median PFS was 21 months (range, 5-66 months) in 22 patients treated with IFXRT alone upon relapse after ASCT. Therefore, in selected patients, use of IFXRT may delay the use of chemotherapy and lead to durable remissions. In addition, it is important to note that a very small number of cHL patients who relapse after ASCT could potentially be cured with radiotherapy.64 Goda et al reported on the outcomes of 34 patients with relapsed/refractory cHL who also had failed ASCT treated with either IFXRT or extended-field radiation therapy. Three patients with localized relapse after ASCT achieved a CR after IFXRT and remained disease-free with a median follow-up time from IFXRT of 6.4 years (range, 5.6-7.4 years).64 The patients who appear to potentially benefit the most from this approach are those with PET/CT documented stage I or II disease at relapse, disease confined to previously unirradiated lymph nodes and without B symptoms.

Efficacy of single-agent chemotherapies including gemcitabine, etoposide, vinorelbine, vinblastine, liposomal doxorubicin, and bendamustine ranges from 30% to 72% in patients with relapsed cHL (Table 1).37-43 Santoro et al reported an ORR of 39% and a median duration of response of 6.7 months in relapsed/refractory cHL patients treated with gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle.38 In a study by Venkatesh et al, 5 of 16 evaluable patients with prior ASCT achieved a PR with gemcitabine, with a median PFS of 6.4 months.37 Little et al retrospectively reviewed the activity of vinblastine given at 4 to 6 mg/m2 every 1 to 2 weeks in 17 patients.40 Ten (59%) had an objective response, 2 achieved a CR, and the median EFS was 8.3 months. With weekly vinorelbine administered until disease progression, responses were observed in 50% of patients for 2 to 10 months.41 More recently, the ORR of bendamustine at 120 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks in 26 relapsed/refractory cHL patients after previous ASCT was 57% (CR 38%).42 These studies collectively demonstrate the variety of single-agent chemotherapy regimens available for patients with relapsed cHL. Many of these agents can be continued until best response or disease progression.

For those patients with extranodal or organ involvement who are symptomatic or who need an optimal response prior to allogeneic SCT, many interchangeable combination chemotherapy regimens can be considered (Table 2).44-57,66,67 These regimens have been largely used as salvage treatment options in the pre-ASCT setting leading to ORRs of 69% to 100%. Limited data on the use of these combinations are available in the post-ASCT setting; however, when used post-ASCT, most of these regimens are associated with higher rates of grade 3-4 myelosuppression than observed in transplant-naive patients. For example, Bartlett et al reported the results of the combination of GVD in 91 patients, 36 with prior ASCT.44 In patients with prior ASCT, ORR was 75% (17% CR) compared with an ORR of 62% (20% CR) in the transplant-naive patients. In the previously transplanted patients, grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were noted in 51% and 43% of the patients, respectively, compared with 63% and 14% in the transplant-naive group. Aparicio et al reported the results of 3 to 6 cycles of ESHAP in 22 patients.48 ORR was 73% (40% CR) and 3-year PFS was 27%. Overall, grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were both noted in 33% of the patients with 1 patient who died of septic shock. With DHAP, the ORR was 89% (21% CR) with similar results in patients with early, late, or multiple relapses.50 ORRs of 88% to 100% have been reported with ICE and 81% have been reported with IGEV; however, the majority of the patients in these trials had relapsed after only 1 prior therapy and received these treatments prior to planned ASCT.51-53

In addition to risks of myelosuppression, combination chemotherapy regimens also increase the risk of secondary malignancy in cHL long-term survivors.68,69 Therapy-related AML and MDS typically occur in a dose-dependent manner 2 to 8 years after initial treatment of HL with alkylating agents and topoisomerase inhibitors. Salvage chemotherapy and conditioning regimen for ASCT contribute significantly to the increased risk of AML/MDS in these patients.70,71 For example, in the original GVD publication, 3 patients developed t-AML/MDS after ASCT.44 For this reason, we favor use of combination therapies for a limited duration (maximum 4-6 cycles) and only in specific circumstances where a rapid and significant response are necessary, that is, in patients with organ involvement, symptoms, or to achieve best response prior to allogeneic SCT. Furthermore, attention must be paid to cumulative anthracycline dose and pretreatment ejection fraction if anthracycline-containing regimens are used in the relapsed setting.

Checkpoint inhibitors and immunomodulatory therapy

Over the last few years there has been a growing interest in modulating the extensive but ineffective inflammatory and immune cell infiltrate surrounding Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells. RS cells express high levels of PD1 ligands (PD-L1) and by engaging PD-1–positive immune effector cells, tumors can evade the immune response.72 Chromosome 9p24.1 amplification is a recurrent abnormality in nodular sclerosis cHL and the genes encoding PD-L1 are key targets of this amplification.73 The 9p24.1 amplicon also includes Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and JAK2 amplification induces PD-L1 transcription.73 In addition, Epstein-Barr virus, found in some cases of cHL, also increases the expression of PD-L1.74 In a phase 1 study of the PD-1–blocking antibody, nivolumab, 23 patients with cHL (including 18 patients previously treated with brentuximab and 18 patients relapsing after ASCT) received nivolumab every 2 weeks until disease progression or for a maximum of 2 years.29 The ORR was 87%, with 17% CR, and PFS at 24 weeks of 86%. Drug-related grade 3 adverse events included MDS, pancreatitis, pneumonitis, stomatitis, colitis, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. With pembrolizumab, another anti-PD1 antibody, the ORR was 53% (20% CR) in 15 patients with cHL, all previously treated with brentuximab and 67% failing prior ASCT.30 Confirmatory phase 2 studies are under way with checkpoint inhibitors in cHL (NCT02181738, NCT02362997).

Three separate studies have confirmed the activity of lenalidomide in cHL.31,58,59 A multicenter study from Fehniger et al reported an ORR of 19% and a cytostatic ORR (CR, PR, and stable disease [SD] lasting longer than 6 months) of 33% in 38 cHL patients including 31 patients with prior ASCT. Median duration of response was 6 months (range, 4-24 months) and median time to treatment failure was 15 months (range, 4-43 months).31 Similar results were also obtained in 2 smaller studies with lenalidomide in heavily pretreated cHL patients and ORR ranged from 14% to 50%.58,59

Unlike cHL cells, reactive B cells in the cHL microenvironment express high levels of CD20.75 In a pilot study, 22 patients with relapsed/refractory cHL, 18 of them with prior ASCT, were treated with rituximab 375 mg/m2 once a week for 6 consecutive weeks. The ORR was 22%, with 1 patient achieving a CR and 4 patients achieving a PR, and a median duration of response of 7.8 months.60 Rituximab has subsequently been added to other salvage chemotherapy options in cHL, but the impact of its addition to these regimens remains unclear.76

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, and other novel agents in cHL

Response rates with everolimus and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors rival those observed with lenalidomide in patients with relapsed cHL. An ORR of 47% (1 CR) and 7.2-month response duration has been reported with everolimus in 19 patients with relapsed cHL.32 Grade 3 and 4 toxicities include thrombocytopenia (32%), neutropenia (5%), and anemia (32%). In addition, 4 patients had pulmonary toxicity including pneumonitis, dyspnea, and pleural effusions. Therefore, caution should be exercised if considering use of everolimus in patients with pulmonary manifestations of cHL or in patients with preexisting pulmonary complications from bleomycin, ASCT, IFXRT, or gemcitabine.

Panobinostat appears to be the most active HDAC inhibitor tested in patients with cHL. A phase 2 study in 129 cHL patients reported an ORR of 27%, with 5 patients achieving CR. In addition, 71 patients achieved a best response of SD, with a median PFS of 10.6 months for responders and 5.6 months for patients with SD.33 In a phase 1 study of panobinostat in combination with everolimus, ORR was 43%, similar to that observed with everolimus alone. In addition, in a phase 1/2 study of panobinostat and lenalidomide, only 14% of 21 cHL responded, raising the question of whether there is any additional benefit of these agents in combination.77

Therefore, as demonstrated by this case, a variety of options are available for a patient with relapsed cHL following ASCT, including observation, IFXRT, single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy, and novel agents. We typically favor clinical trial participation for all patients with relapsed cHL when available; however, in patients where this may not be an option and who have previously received brentuximab, we would currently recommend a checkpoint inhibitor as the next line of therapy given the impressive ORR with these agents. Results from ongoing phase 2 studies with these agents will better direct our use of these agents in the future in patients with relapsed cHL. Following therapy with a checkpoint inhibitor, patients will likely receive a variety of single agents or combination therapies depending on their disease burden and severity of symptoms over the course of their disease. It is important to try and minimize therapy in asymptomatic patients and observation or limited IFXRT is acceptable in these patients in order to delay the potential risks of therapy-related MDS and AML.

Case presentation 3

A 32-year-old man presented with stage IVB cHL with involvement of multiple extranodal sites including bone marrow, liver, lungs, spleen, T10, and L4 vertebral body. He received 6 cycles of ABVD with a negative PET/CT after cycles 2 and 4. However, after cycle 6, PET/CT demonstrated a new liver lesion and intra-abdominal adenopathy. Biopsy of the liver was consistent with cHL; he then received 3 cycles of ICE followed by ASCT. Eighteen months post-ASCT, he had recurrent mediastinal and intra-abdominal adenopathy and biopsy again confirmed relapsed cHL. He received 14 doses of brentuximab, achieving a CR on PET/CT. He subsequently underwent unrelated 10 of 10 HLA-matched allogeneic SCT with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen with fludarabine, busulfan, and antithymocyte globulin. He is currently 30 months posttransplant, and disease-free without graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Role of second ASCT and allogeneic SCT in relapsed cHL

A second autograft has been considered an option for cHL patients who relapse after previous ASCT; however, the data supporting this approach in cHL are limited. It appears that a second ASCT could be beneficial for those patients who relapse >12 months after initial ASCT.78 Smith et al reported on 40 patients, 21 of whom had cHL, undergoing second ASCT: the 5-year PFS and OS for patients relapsing within 12 months were 0% and 13% compared with 32% and 41% for patients relapsing after 12 months (P = .001 and 0.002, respectively).78 The time to relapse after the first ASCT was the strongest predictor of improved outcome with no benefit shown from second ASCT for those cHL patients who were refractory to the first one.

Allogeneic SCT may also represent a treatment option for cHL patients who relapse after ASCT and multiple retrospective and prospective studies support its use in selected cHL patients.79-84 In a retrospective trial from the European Bone Marrow Transplant (EBMT) group,80 168 cHL patients underwent either RIC allogeneic SCT (n = 89) or myeloablative allogeneic SCT (n = 79).80 Although the treatment-related mortality (TRM) was significantly higher in the patients with myeloablative approach, there was no statistically significant difference in 5-year PFS and OS between the RIC and myeloablative group (PFS: 18% RIC vs 20% myeloablative, P = .6; OS: 28% RIC vs 22% myeloablative, P = .06). Similar results were reported by Tomblyn et al.82 In their study, 141 patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma (26 cHL) underwent either nonmyeloablative or myeloablative allogeneic SCT and no statistical significant difference in 3-year PFS and OS between the 2 groups was noted. These results on outcomes of cHL patients undergoing RIC allogeneic SCT are consistent with those of other retrospective studies where estimated 2-year PFS of 29% to 39% and 2-year OS of 52% to 66% have been reported.81,83,85 These findings have also been recently confirmed in a prospective study of 78 cHL patients who underwent RIC allogeneic SCT with 4-year PFS and OS rate of 18% and 43%, respectively.84

Although the type of donor (matched related or unrelated) does not seem to affect the prognosis, a retrospective study on 90 relapsed/refractory cHL patients who underwent RIC allogeneic SCT reported a statistically significant PFS advantage and lower nonrelapse-related mortality with similar incidence of acute and chronic GVHD for haploidentical SCT over matched related or unrelated donor.86 In support of the role of haploidentical SCT for relapsed cHL after ASCT, Raiola et al recently reported an encouraging 3-year PFS and OS rate of 63% and of 77%, respectively, in 26 cHL patients who received a haploidentical SCT following a nonmyeloablative conditioning regiment and posttransplant high-dose cyclophosphamide for GVHD prophylaxis.87 In addition, the TRM was 4% and the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD and of chronic GVHD was 24% and 8%, respectively. Recent data also suggest that double umbilical cord blood transplantation may be an effective approach for cHL patients who relapse after ASCT. Thompson et al treated 27 cHL patients: 15 received myeloablative and 12 nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens. ORR was 68% (with 58% CR), median PFS was 12 months and median OS was 27 months.88 Finally, emerging data show that treatment with brentuximab vedotin before RIC allogeneic SCT for relapsed cHL may lead to prolonged PFS. Chen et al treated 21 brentuximab-naive cHL patients with brentuximab prior to RIC allogeneic SCT and retrospectively compared transplant-related complications and outcomes to 23 patients with similar clinical characteristics who received RIC allogeneic SCT without brentuximab. Two-year PFS rates were significantly better in those patients who received brentuximab (59.3% vs 26.1%), however, no significant differences in OS or TRM were noted.89

Although we do not routinely recommend a second ASCT for patients with recurrent cHL, it is reasonable to consider this for patients with late relapses who may not have an available donor for allogeneic SCT; however, the risks of therapy-related MDS and secondary AML have to be taken into consideration with this approach. For younger patients with an available donor and a low comorbidity index, we do offer allogeneic SCT. Many factors play a role in the decision to proceed with allogeneic SCT, including type and matching of donor, patient age, patient comorbidities, chemosensitivity, patient compliance, TRM, and risks of long-term GVHD; for these reasons, evaluation by a specialized bone marrow transplantation team is strongly recommended before proceeding with this approach.

Final considerations

Although cHL is a highly curable disease with modern chemotherapy, some patients are primary refractory, relapse after first-line chemotherapy, or relapse after high-dose therapy and ASCT.90-92 High-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT leads to 3-year PFS rates of 50 to 60% in patients with relapsed cHL patients and 40% to 45% in patients with chemorefractory disease.8,9,14 Although only a subset of cHL patients relapses after ASCT, this is a difficult-to-treat patient population with a median OS of 1 to 2 years. Multiple pathways are dysregulated in cHL, including nuclear factor-κB, phosphatidylinositol kinase/AKT, mammalian target of rapamycin, and cell-surface receptors signaling through CD30 and CD40, as well as an ineffective immune cell infiltrate leading to malignant RS cell escape.93,94 Many biological agents are currently in clinical development, and some of them have shown significant activity in this setting (lenalidomide, everolimus, and panobinostat).31-33 The most promising are brentuximab26,28 and the immune checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.29,30

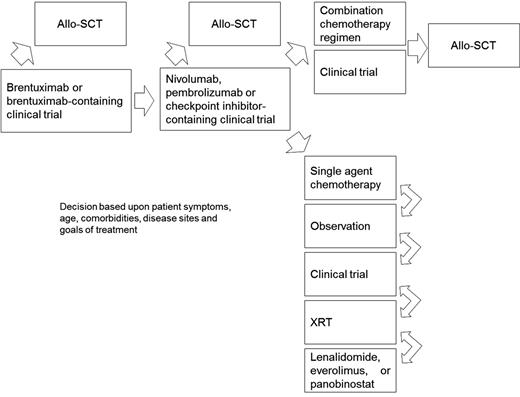

A proposed algorithm for the treatment of cHL patients relapsed after ASCT is shown in Figure 1. For those patients with high-risk disease at the time of ASCT (defined as extranodal involvement, relapse <12 months from front-line chemotherapy, or refractory disease), we recommend post-ASCT consolidation with brentuximab per the AETHERA study.35 For patients with relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT who have never received brentuximab, this should be offered at the time of relapse, as patients achieving a CR may have a prolonged remission duration exceeding 4 years.36 Following brentuximab, we recommend either participation in a clinical trial, checkpoint inhibitors, single-agent chemotherapy, IFXRT, or observation in selected cases. If the ORR in multicenter phase 2 studies with checkpoint inhibitors holds up and is comparable to results from initial phase 1 studies with nivolumab and pembrolizumab,29,30 this approach should probably be offered after brentuximab as few chemotherapy regimens approach this efficacy in the relapsed setting.

Suggested algorithm for the treatment of cHL patients who relapse after ASCT. Allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; XRT, radiation therapy.

Suggested algorithm for the treatment of cHL patients who relapse after ASCT. Allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; XRT, radiation therapy.

Due to the risks of t-AML and greater toxicity, combination chemotherapy strategies should be reserved for symptomatic patients with either a large disease burden or extranodal disease, or those who are allogeneic SCT candidates. Allogeneic SCT may offer prolonged disease control to selected patients with a suitable HLA-matched donor, although the risks of TRM and long-term GVHD must be taken into consideration with such an approach. Novel approaches, including the use of chimeric antigen receptor T cells targeting CD30 (NCT02277522; NCT02259556; NCT02274584), are currently under investigation for patients with cHL and may offer exciting new options for the treatment of these patients.

Authorship

Contribution: L.A. and K.A.B. both wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.A.B. receives research funding from Novartis, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Cephalon, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. L.A. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lapo Alinari, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 320 West 10th Ave, 406C-1 Starling Loving Hall, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: lapo.alinari@osumc.edu.