To the editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is caused by lesions arising from myeloid dendritic cells that present in a variety of organ systems ranging from single bone or skin lesions to diffuse multisystem disease.1 Survival for patients with LCH limited to skin or bone is nearly universal, but many patients relapse and can require multiple therapies to achieve a durable remission. One retrospective review found that 40% of patients relapsed at least once.2 Patients who relapsed had a twofold increased risk of permanent consequences such as diabetes insipidus and neurodegenerative disease. Skin-only LCH has a favorable prognosis and can resolve spontaneously or respond to minimal chemotherapy. However, 24% of patients with multisystem disease who relapsed developed skin or other nonbone single-system disease, some relapsing with skin involvement a second time.2 Another institutional series reported that among patients with LCH limited to the skin who required treatment, 11% relapsed. Patients with skin and another disease site treated with vinblastine and prednisone have a 56% chance of relapse.3 Despite generally favorable outcomes in patients with skin LCH, a subset of patients develop chronic rashes or oral lesions that respond slowly to treatment with oral methotrexate (MTX), mercaptopurine, or prednisone and IV vinblastine or cytarabine. There is no clear standard of care for the management of cutaneous LCH. Similar to skin-only LCH, bone-only LCH is associated with minimal mortality, but patients with multiple bone lesions have increased rates of relapse and permanent consequences. Minkov et al found that single-system skeletal relapse was the most common site of recurrence.2 Twenty percent to 30% of patients with bony disease develop permanent orthopedic sequelae, such as vertebral collapse or facial asymmetry.4-6 In addition to complications specific to skin and bone LCH, patients with uncontrolled LCH or multiple relapses may develop long-term morbidities including chronic pain, endocrinopathies, and neurodegenerative symptoms.6

Given that the pathologic CD207+ dendritic cells in LCH arise from myeloid precursor cells driven by activating mutations in the MAPK pathway, we hypothesized that therapies directed against immature myeloid cells may be effective in the treatment of LCH. Hydroxyurea (HU) is a myelotoxic ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor with proven efficacy in other neoplasms of myeloid origin, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia, essential thrombocythemia, and polycythemia vera.7,8 We report a single-center experience with HU or HU/MTX therapy in a cohort of LCH patients with skin and/or oral lesions, skin and bone, bone only, or lymph node involvement.

The charts of 15 patients treated at Texas Children’s Hospital from November 2013 to April 2016 were reviewed in accordance with institutional review board–approved protocols at Baylor College of Medicine. Patients were selected for HU therapy based on specific clinical characteristics: recurrent or refractory skin or bone disease, either alone or in combination with lymph node involvement, following standard-of-care frontline therapy or intolerance of other therapies. Treatment response was reported using modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), as applied to lymphomas, criteria: complete resolution (CR), partial resolution (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD).9 Bone lesion responses for those >10 mm on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan were tracked with serial imaging. Unmeasurable lesions such as rashes were followed by changes in examination as documented by the physician. Pediatric patients were started at a dose of 20 mg/kg divided twice daily and adult patients were started at a dose of 500 mg twice daily. Five patients were treated with a combination of HU/MTX after PR or SD with HU alone. Methotrexate was given at 5 to 10 mg twice weekly. Treatment doses were titrated to maximum effect, with a target absolute neutrophil count of 1000 to 1500.

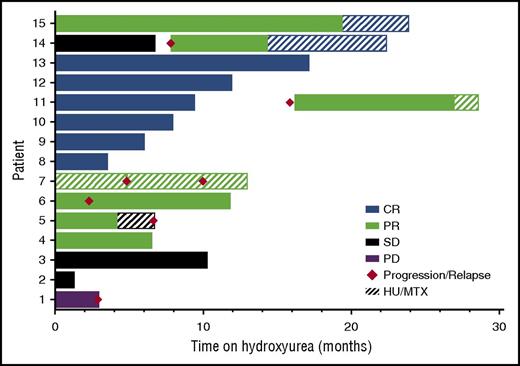

Fifteen patients with relapsed/refractory LCH of skin and bone (4), skin and/or oral only (8), bone only (2), and skin, oral, and lymph node (1) were identified for HU treatment, following previous treatment with 1 to 5 regimens. The median age at initiation of HU was 41.2 years, ranging from 2.5 to 73.2 years. The median duration of therapy was 10 months, ranging from 1 to 24 months (Table 1). In patients treated with HU alone, best responses achieved included CR in 6 of 14 patients (43%), PR in 5 of 14 patients (36%), SD in 2 (14%), and PD in 1 (7%). In 4 patients achieving PR on HU therapy alone, and in 1 patient who had previously achieved PR on MTX alone, HU was used in combination with MTX, resulting in eventual CR in 2 of these patients (Figure 1), for total response rates of 80% (53% CR, 27% PR). Following treatment with HU, 6 patients (40%) had progression of symptoms or relapsed after initial response. The median time to disease progression/relapse was 5.7 months, ranging from 1 to 17 months. Of the 6 patients, 4 (67%) progressed or developed recurrent symptoms while taking HU and 2 (33%) after stopping therapy; these 2 patients again achieved disease response with reinitiation of HU therapy. Grade 3-4 toxicity was limited to anemia and neutropenia in 1 patient requiring blood transfusion and dose reduction, and thrombocytopenia and neutropenia in a second patient, requiring temporary dose reduction, but with no serious infections or adverse events throughout the course of HU therapy.

Response to HU therapy. Best clinical responses of 15 relapsed/refractory LCH patients treated with HU (± MTX) therapy. Eight of 15 patients (53%) showed CR, 4 of 15 (27%) showed PR, 2 of 15 (13%) showed SD, and 1 of 15 (7%) showed PD when treated with HU therapy alone, or in combination with MTX. Six of 15 patients (40%) progressed or relapsed (2 off HU therapy, and 4 on HU therapy); 2 of 6 patients (33%) had PR after HU reinitiation, and MTX was added in both cases, with CR in patient #14. The addition of MTX to patient #11 lead to ongoing improvement, but not CR. Patient #5 had initial PR to HU and no additional benefit after MTX was added.

Response to HU therapy. Best clinical responses of 15 relapsed/refractory LCH patients treated with HU (± MTX) therapy. Eight of 15 patients (53%) showed CR, 4 of 15 (27%) showed PR, 2 of 15 (13%) showed SD, and 1 of 15 (7%) showed PD when treated with HU therapy alone, or in combination with MTX. Six of 15 patients (40%) progressed or relapsed (2 off HU therapy, and 4 on HU therapy); 2 of 6 patients (33%) had PR after HU reinitiation, and MTX was added in both cases, with CR in patient #14. The addition of MTX to patient #11 lead to ongoing improvement, but not CR. Patient #5 had initial PR to HU and no additional benefit after MTX was added.

This case series shows that HU has activity against LCH in many patients, as 12 of 15 patients (80%) had either partial or complete responses. Recent studies showing the pathologic cell of origin to be a myeloid precursor cell rather than a terminally differentiated Langerhans cell have led to the recommendation that LCH be reclassified as a myeloid dendritic cell neoplasm.10-13 It is therefore not surprising that HU would be effective in the treatment of LCH given its proven efficacy in treating other myeloid disorders.8,14 Historically, adult patients have tolerated HU well. Use in children is also reasonable given extensive experience in the treatment of children with sickle cell disease has proven HU to be both well tolerated and safe for prolonged use.15,16 The toxicity profile of daily oral HU is favorable when compared with alternative salvage therapies such as cytarabine, cladribine, or clofarabine.17 Since the discovery of BRAF-V600E and other recurrent mutations in the MAPK signaling pathway,11,18-20 MAPK pathway inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, are another potential treatment option. However, these agents carry significant risk, including de novo squamous cell carcinoma in 20% to 25% of adults with melanoma,21,22 and little is known about the toxicity profile of long-term MAPK inhibition in pediatric patients. HU may prove to be a safe and effective therapeutic option for some LCH patients with the added benefits of low cost and ease of administration. In conclusion, our series showed HU alone or in combination with MTX to have promising activity in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory LCH, with 80% of patients having partial or complete responses with minimal toxicity. Strategies for future investigation include prospective trials randomizing HU against MTX for patients with skin-limited LCH; randomizing HU vs mercaptopurine as part of initial combination therapy for patients with high-risk organ involvement; or randomizing HU against observation alone as maintenance therapy for both low- and high-risk LCH.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the HistioCure Foundation (Texas Children’s Cancer Center Histiocytosis Program). Additional grant support includes National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute R01 (CA154489), NIH Specialized Programs of Research Excellence in Lymphoma (P50CA126752), and a Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center support grant (P30CA1215123).

The authors have no significant financial interest in, or other relationship with, the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

Contribution: All authors participated in clinical history review and data analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kenneth L. McClain, Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Centers, Baylor College of Medicine, 6701 Fannin St, Suite 1510, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: klmcclai@txch.org.

References

Author notes

D.J.Z. and A.B.G. contributed equally.