Abstract

Background:

Due to underlying liver disease and the transplant process itself, pediatric abdominal transplant patients are at significant risk for bleeding and thrombotic complications. Hemostasis in these patients is nuanced, reflecting a balance of pro- and anti-coagulant factors not accurately captured by routine coagulation lab testing. Previous studies of pediatric liver transplant estimate thrombotic complications in up to 19% of patients and bleeding in 5-9%. These hematologic complications increase risk for graft failure, re-transplantation, or death.

Methods:

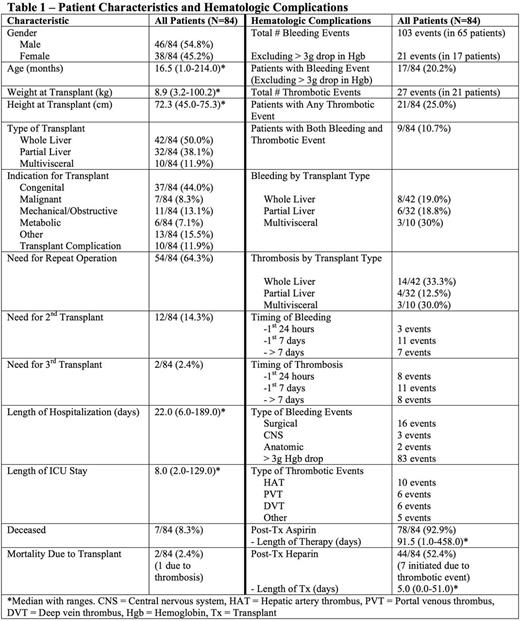

We retrospectively reviewed electronic medical records of consecutive pediatric liver andmultivisceraltransplants at Duke University Medical Center between January 2010 and December 2015 (one exclusion due to inability to access chart). We extracted data from 30 days pre-transplant to 90 days post-transplant. Thrombotic events were defined as any documented thrombus by imaging or direct observation during a surgical procedure. Major bleeding events included surgical bleeding requiring re-operation, CNS bleed, bleeding into an enclosed anatomic space, or blood loss resulting in > 3g/dl drop in hemoglobin. Data was entered into aRedCapDatabase and analyzed usingunivariablelogistic regression.

Results:

There were 84 transplants at Duke from 2010-2015 (Table 1). There were 103 major bleeding events in 65 patients (incidence 77.4%) and 27 thrombotic events in 21 patients (incidence 25%). Excluding events that were only a > 3g/dl drop in hemoglobin, there were 21 bleeding events in 17 patients (incidence 20.2%). Patients on prophylactic aspirin were less likely to have a thrombosis and were not more likely to have bleeding (Table 2). Patients who received prophylactic heparin (initiated prior to any event) did not have a decreased risk of thrombosis nor increased bleeding (Table 2). There was a higher rate of thrombosis and bleeding in patients who had prior GI surgery (Table 2). Use of an arterial conduit was associated with increased bleeding but not thrombosis (Table 2). Patients with a post-op fibrinogen nadir < 75mg/dl had increased bleeding whereas fibrinogen > 75mg/dl was associated with increased thrombosis (Table 2). Patient age, weight, donor to recipient weight ratio, and transplant type were not associated with bleeding or thrombosis. Maximum INR (pre, intra or post-operatively) or minimum antithrombin(<70%, measured in 43% of patients) werealso not associated with bleeding or thrombosis. Fifty-four patients (64%) required repeat operation within 90 days post-transplant, 9 for bleeding and 10 for thrombotic complications. Nine patients required re-transplant for thrombotic complications. No bleeding events necessitated re-transplantation. Seven patients were deceased at time of review. Two deaths were attributed to transplant, one from graft failure due to vascular thrombosis (portal vein and hepatic artery) that occurred 2 days after transplant. In response to an increase in thrombotic events around 2013, clinical practices changed to utilize increased heparin prophylaxis and antithrombinsupplementation. There has been an increase in total number of bleeding events since those practice changes were implemented (Figure 1), however the event rate per number of transplants remains similar.

Discussion:

We found that bleeding events were more frequent than reported in previous cohorts, but notably less severe than thrombotic complications. In our cohort, many thrombotic complications were severe and potentiallylife-threatening. Practice changes aimed to decrease thrombosis may have led to an increase in recent bleeding events, but these events generally did not result in significant morbidity. Bleeding often required intervention, but did not contribute to re-transplantation or mortality during this period. Laboratory parameters predicted adverse events poorly, apparently failing to capture the nuanced and dynamic interplay between pro- and anti-coagulant factors in the post-transplant patient. A standard approach to coagulation testing combined with a protocol for use of anti-thrombotic therapies may be useful for prospective study. Regular review of outcomes can demonstrate changes that may impact future practice. Further study aimed at delineating parameters associated with adverse outcomes-possibly other than standard coagulation assays-is warranted.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.