Abstract

Introduction

The complete blood count is one of the most frequently ordered patient blood test. It provides the most basic hematological measurements including hematocrit (Hct), white blood cell count (WBC), and platelet count (PLT). An increase in some of these markers have been shown to be associated an increased thrombotic risk. Most notablyHctfor patients with polycythemiaveraand WBC and PLT in cancer patients. Some population studies have shown an increased propensity of thrombosis among healthy individuals with elevatedHct. However these studies have not included sufficient clinical data to account for potential confounders. The aim of this study is to assess whether elevation of these hematological markers are risk factors for thrombosis in the general population.

Methods

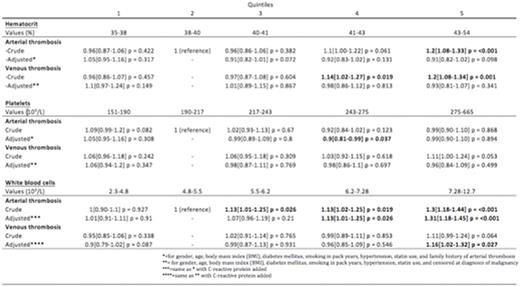

Complete blood count and baseline characteristics were obtained from participants in the Reykjavik-AGES study at enrollment in 2002. The Reykjavik-AGES study, a nationwide screening study of 5755 elderly individuals, includes thorough medical history, physical examination, and blood measurements. Lifetime incidents of thrombotic events were recorded up to 2015 in the Icelandic National Health Service and cross-linked to the participants of the study through the National Registry of the total Population. Primary outcomes of arterial and venous thrombosis were considered separately 10 years before and after enrollment. Hct, WBC, and PLT were used to determine exposure and stratified into five quintiles in four respective analyses. The second quintile was used as a reference group. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to determine hazard ratios and confidence intervals. We then adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking (in pack years), hypertension and statin use. For arterial thrombosis we also adjusted for family history of arterial thrombosis and for venous thrombosis we censored at diagnosis of malignant neoplasm. In the analysis of WBC we also adjusted for C-reactive protein, an acute phase protein. Individuals with abnormal values of these parameters were excluded from the study (PLT < 150x109/L, WBC > 13x109/L or < 2.0,Hct < 35% were excluded)

Results

Crude analyses ofHctrevealed a dose dependent increased risk of arterial (hazard ratio (HR) 1.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08-1.33, p<0.001) and venous (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.80-1.34, p=0.001) thrombosis with increasing values. However, after adjusting for confounders there was no association (Table). There was no association between higher levels of PLT and increased risk of thrombosis (Table). Analysis of WBC showed a dose dependent increase in risk for arterial thrombosis (HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.18-1.45, p<0.001) after adjusting for confounders. A similar but weaker effect was found for venous thrombosis (HR 1.16, 95% CI1.02-1.32, p=0.027).

Conclusion

In this large population-based prospective cohort study including detailed clinical information on 5755 elderly individuals, we observed no association of elevatedHctor PLT with risk of arterial or venous thrombosis after adjusting for confounders. However, we found a clear increase in the thrombotic risk associated with higher WBC, especially for arterial thrombosis. We speculate this may be due to a higher baseline of leukocyte activation and a low-grade inflammatory state. These factors have been shown to play a part in thrombotic pathways. We therefore conclude WBC to be a marker for thrombotic risk within the general population.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.