Key Points

Delivering IL-21 to tumor B cells by fusion with anti-CD20 antibody (αCD20-IL-21 fusokine) is a potent antilymphoma therapeutic strategy.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine demonstrated superior antilymphoma activity compared with its individual components.

Abstract

In spite of newly emerging therapies and the improved survival of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), relapses or primary refractory disease are commonly observed and associated with dismal prognosis. Although discovery of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab has markedly improved outcomes in B-cell NHL, rituximab resistance remains an important obstacle to successful treatment of these tumors. To improve the efficacy of CD20-targeted therapy, we fused interleukin 21 (IL-21), which induces direct lymphoma cytotoxicity and activates immune effector cells, to the anti-CD20 antibody (αCD20-IL-21 fusokine). We observed substantially enhanced IL-21R-mediated signaling by the fusokine compared with native IL-21 at equimolar concentrations. Fusokine treatment led to direct apoptosis of lymphoma cell lines and primary tumors that otherwise were resistant to native IL-21 treatment. In addition to direct cytotoxicity, the fusokine enhanced NK cell activation, effector functions, and interferon γ production, resulting in greater antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity compared with IL-21 and/or anti-CD20 antibody treatments. Further, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine stabilizes IL-21 and prolongs its half-life. In vivo αCD20-IL-21 therapy resulted in a significant tumor control in the rituximab-resistant A20-huCD20 tumors. Collectively, the dual functional ability of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine to induce direct apoptosis and activate immune effector cells may provide benefit over existing treatments for NHL.

Introduction

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) are traditionally treated with chemotherapy. Addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) rituximab to chemotherapy has substantially improved treatment outcomes in NHLs, enhancing response, prolonging progression-free survival, and improving survival in both indolent and aggressive lymphomas.1 However, response to rituximab-containing regimens is not universal and is associated with primary refractoriness or disease relapse.2 Since the development of rituximab, considerable efforts have been made to design new CD20 mAbs, resulting in the recent approval of next-generation, fully humanized Abs ofatumumab and obinutuzumab. Although these Abs showed better activity in vitro and in xenograft models,3 results from the present clinical trials are unclear as to whether they are better than rituximab, as these novel Abs were used at an optimized pharmacokinetic schedule, but the rituximab schedule was not pharmacokinetically optimized.4,5 This suggests novel approaches are urgently needed to improve the efficacy of the current anti-CD20 Ab-based therapies.

The in vivo antilymphoma effects of rituximab and other CD20 mAbs are mediated by Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), phagocytosis, and direct apoptosis.6,7 ADCC, mediated by engagement of immune cells via the Fc receptor, is the dominant determinant of therapeutic efficacy of Abs in many NHLs.8 Nonmalignant immune cells (eg, natural killer [NK] and T cells) frequently found in the tumor microenvironment play important roles in lymphoma pathogenesis and eradication. Indeed, mechanistic studies in xenograft mouse models demonstrated that NK cells expressing CD16 (Fc γ receptor III [FcγRIII]) are indispensable for the therapeutic efficacy of mAbs.9,10 Concordantly, patients harboring FcγRIIIA polymorphism with higher NK affinity for immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) showed better response to rituximab therapy.11,12 This implies that therapeutic strategies that potentiate NK cells’ functional ability to enhance ADCC may result in better lymphoma cell eradication. Combining immunotherapy approaches to activate NK cells and enhance ADCC has demonstrated improved therapeutic efficacy in B-cell lymphoma tumor models.13,14 For example, combination of anti-CD137 mAb and rituximab, where the latter upregulates CD137 on NK cells, resulted in increased ADCC.15 Combining mAbs with immunomodulatory molecules such as Toll-like receptor agonist (CpG ODN) or NK cell stimulatory NKG2D ligand or blocking Abs to NK cells’ negative regulator (killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, KIR) have also shown promising results in preclinical studies.16-19 Strategies combining mAbs with cytokines stimulating effector cells have also been attempted to enhance ADCC activity.13,20-23

Interleukin-21 (IL-21), a member of the IL-2 cytokine family, is a potent immunostimulatory cytokine exhibiting diverse regulatory effects on NK, T, and B cells.24,25 IL-21 possesses antitumor activity against a variety of cancers not expressing IL-21 receptor (IL-21R) through activation of the immune system.26-31 We and others recently showed that IL-21 enhances rituximab-mediated ADCC of NHL cells, including mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemias.20,32,33 Similarly, increased ADCC was also observed in a murine breast cancer model treated with the anti-HER2 Ab (trastuzumab) and IL-21.21,34

Apart from its immunostimulatory effects, IL-21 exerts direct cytotoxicity on a variety of IL-21R-expressing NHLs, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), MCL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and follicular lymphoma.32,35-42 We found that the direct apoptotic effects of IL-21 in DLBCL and MCL were mediated via activation of an IL-21R-dependent signaling pathway that leads to phosphorylation of STATs followed by upregulation of cMyc and Bax and downregulation of BCL-2 and BCL-XL.32,35 These studies suggest IL-21 may become a potent adjuvant to cancer immunotherapy against B-cell lymphoma.37 Indeed, a recent clinical trial of IL-21 in combination with rituximab for relapsed or refractory low-grade B-cell lymphomas showed clinical responses in 8 (42%) of 19 patients, with a response rate of 33% in rituximab-resistant patients.38 This suggests that the addition of IL-21 may have allowed some patients to improve on their last response to rituximab.

However, systemically administered cytokines are limited in their therapeutic efficacy because of their inability to achieve optimal concentration in the tumor bed, as well as dose-limiting toxicity. To overcome these issues, fusion of cytokines to mAb, referred to as fusokines or immunocytokines, were examined. In preclinical studies, fusion of type I interferons (IFNα/β) with CD20 mAb demonstrated potent antilymphoma effects in B-cell lymphoma tumor models.39,40 Fusion of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and IL-21 (GIFT-21) activated immune response and led to antitumor responses in the B16 xenograft model.41 A recent study of IL-2 fusion with fragment constant (Fc) region (Fc/IL-2) resulted in significant tumor control in isogenic tumor models.42 Collectively, these studies suggest fusokine therapy may represent a potent therapeutic approach to NHLs.

As a consequence, we hypothesized that fusing IL-21 to an anti-CD20 Ab may improve IL-21 bioavailability, potentiate IL-21-mediated direct apoptosis, and enhance NK-mediated ADCC, thereby promoting lymphoma cell clearance via dual effects of the fusokine components. Here we report on the development of an anti-CD20 and IL-21 fusion protein (αCD20-IL-21 fusokine) and examine its preclinical efficacy in NHLs.

Methods

Reagents, Abs, cell lines, primary tumors, and in vitro studies

Reagents, cell lines, acquisition of primary tumors, ex vivo studies, and statistical methods are described in the supplemental Materials and Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Mice studies

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol and institutional guidelines defined by University of Miami. CD20 transgenic (CD20-Tg) BALB/c mice (6-8 weeks old) obtained from Warren Shlomchik (Yale University) were bred and housed at the University of Miami.

In vivo IFNγ production.

For in vivo IFNγ production assay, A20-hCD20 cells were incubated at 37°C in complete media with αCD20-IL-21(2 μg/mL) or equimolar concentration of αCD20-IgG1 or normal hIgG for 45 minutes. Cells were washed twice in sterile PBS, and 1 × 106 cells injected intraperitoneally into BALB/c CD20-Tg mice. Animals were randomly divided into 5 treatment groups (n = 3/group): αCD20-IgG1, αCD20-IL-21, hIgG, hIgG treated in vivo with IL-21, and αCD20-IgG1 treated in vivo with IL-21. Mice were bled at 24 hours postinjection, and serum was analyzed for IFNγ content by ELISA (mouse IFNγ ELISA MAX Standard, Biolegend), following manufacturer’s protocol.

Pharmacokinetic studies.

To monitor serum levels of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, CD20-Tg BALB/c mice (4-6 weeks; n = 3/group) were administered a single dose of αCD20-IL-21 (2 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 via tail vein injection. Mice were bled at 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes and at 6, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours postinjection. Blood samples were kept on ice for 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes to separate serum. A quantitative IL-21 ELISA (human IL-21 ELISA MAX Delux, Biolegend) was used to determine serum IL-21 levels, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pharmacokinetic variables were calculated by fitting human IL-21 concentration data to a biexponential model with derivative free nonlinear regression analysis (PK Solution, version 2.0.6; program developed at Summit Research Services). Pharmacokinetic variables, such as serum distribution and elimination, steady-state area under the serum concentration curve, and mean residence time, were calculated.

Tumor studies.

For tumor challenge, 5 × 106 cells were inoculated subcutaneously. Mice with a tumor volume of 100 mm3 were randomly assigned into 1 of 5 treatment groups: 2 µg/mL αCD20-IL-21, equimolar doses of αCD20-IgG1, or/and IL-21 or saline (n = 5 mice/group). Each treatment was continued for 2 consecutive weeks on a daily basis. Mice were followed for survival or until tumor volume reached 1500 mm3. Tumor size was measured using standard calipers, and tumor volume was calculated using a modified ellipsoid formula, where volume = 0.52 × (length × width2 ).

Results

Designing the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine

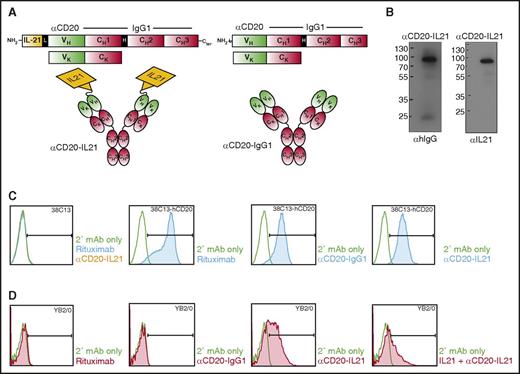

All currently clinically available anti-CD20 Abs demonstrate similar activity in patients and are patent-protected. Therefore, to test the proof of principle that fusion of IL-21 to anti-CD20 may be more effective than naked parent Ab and can effectively target IL-21 to the CD20-expressing tumor B-cells, we generated a fusion of native human IL-21 (hIL-21) to the NH2 terminal domain of anti-CD20 IgG1 Ab derived from a 1F5 hybridoma cell line, termed αCD20-IL-21 fusokine (Figure 1A). For IL-21 fusion at NH2 terminus, we introduced a 15-amino acid Gly4-Ser linker (Figure 1A). An identical αCD20-IgG1 Ab was produced as a control.

Design, characterization, and binding studies of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. (A) Expression cassette and structure of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine (left) and αCD20-IgG1 parent Ab control (right). (B) Immunoblotting of purified fractions of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine under reducing condition using αhIgG and αIL-21 Abs. (C and D) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of indicated Abs with CD20 or IL-21R expressed on 38C13-hCD20 and YB2/0 cells, respectively. Anti-hIgG-FITC was used as secondary (2°) mAb to detect cell bound Abs. CH1, CH2, CH3, constant region of human γ1 heavy chain; H, hinge region; L, 15-amino acid linker (SGGGG)3; V, variable region of αCD20.

Design, characterization, and binding studies of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. (A) Expression cassette and structure of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine (left) and αCD20-IgG1 parent Ab control (right). (B) Immunoblotting of purified fractions of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine under reducing condition using αhIgG and αIL-21 Abs. (C and D) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of indicated Abs with CD20 or IL-21R expressed on 38C13-hCD20 and YB2/0 cells, respectively. Anti-hIgG-FITC was used as secondary (2°) mAb to detect cell bound Abs. CH1, CH2, CH3, constant region of human γ1 heavy chain; H, hinge region; L, 15-amino acid linker (SGGGG)3; V, variable region of αCD20.

To ensure the correct size and assembly of the fusokine, supernatants collected from transiently transfected sp2/0 cells were subjected to [35S]-methionine labeling, followed by immunoprecipitation with protein G beads. Under reducing conditions, αCD20-IL-21 heavy (H) and light (L) chains migrated at ∼88 and ∼25 kDa, respectively, whereas the unfused αCD20-IgG1 H chain was observed at ∼70 kDa (supplemental Figure 1, upper, lane 6). In the absence of reducing agents, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine was resolved at 205 kDa, confirming secretion of the intact protein composed of H2L2 and 2 molecules of fused IL-21 (supplemental Figure 1, bottom). The full-length protein sequence of the fusokine was further confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis (data not shown). For large-scale fusokine production, proteins secreted from stably transfected 293T cells were purified using protein G beads, and eluted fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel, showing an identical band (∼88 kDa) for the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine on immunoblotting with anti-IL-21 or anti-hIgG Abs under reducing condition (Figure 1B).

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine binds its cognate CD20 antigen and IL-21R

To evaluate the binding of fusokine to CD20, we used a murine B-cell lymphoma cell line expressing human CD20, 38C13-hCD20. Both αCD20-IL-21 and αCD20-IgG1 parent Abs bound to the 38C13-hCD20 cells, but not to the parental 38c13 cell line (Figure 1C). The αCD20-IL-21 fusokine also bound to the CD20-expressing lymphoma cell line RCK8 (supplemental Figure 2A). These observations confirmed that fusion of IL-21 to anti-CD20 Ab does not interfere with binding of the Ab to CD20. We also performed immunofluorescence analysis to visualize binding of the fusokine and parent Abs to surface CD20. αCD20-IL-21, parental αCD20-IgG1, and rituximab bound to CD20-expressing Raji cells, but not the anti-EGFR mAb (cituximab), used as a control (supplemental Figure 2B).

Binding of fusokine to the IL-21R is vital for activation of IL-21R-dependent downstream signaling pathways. Therefore, we analyzed whether the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine binds to human IL-21R-expressing mouse hybridoma cell line (YB2/0). As expected, only αCD20-IL-21 fusokine bound to the YB2/0 cells, whereas αCD20-IgG1 did not (Figure 1D). To confirm that the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine and native IL-21 bind at the same site on IL-21R, we performed a similar experiment after preincubation with IL-21 that should bind and block the accessibility of IL-21R to the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. Indeed, preincubation with IL-21 resulted in decreased binding of αCD20-IL-21 to the YB2/0 cells, suggesting the fusokine selectively binds to the IL-21R (Figure 1D). Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis studies also confirmed that only αCD20-IL-21 can bind to the IL-21R-expressing YB2/0 hybridoma cells (supplemental Figure 2C).

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine triggers direct apoptosis of B-cell lymphomas

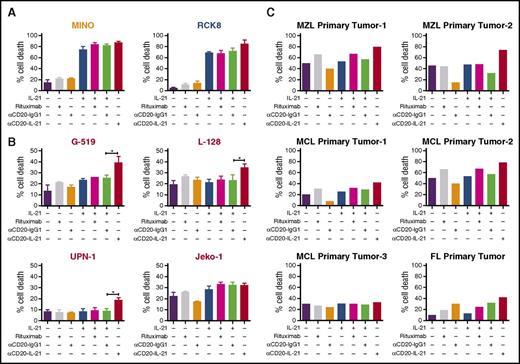

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, we used DLBCL (RCK8, WSU-NHL, Farage) and MCL (SP-53 and Mino) cell lines that are sensitive to native IL-21. To compare the efficacy of the fusokine to native IL-21, we selected an IL-21 dose that led to maximal killing (50 ng/mL), based on our prior studies and reports in the literature.20,35 Cells were exposed to equimolar doses of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine and IL-21. αCD20-IL-21 induced nearly equivalent or slightly higher cell death compared with native IL-21 or its combination with the parental Ab, suggesting its biological activity is retained (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3A). Because in the absence of effector cells, CD20 Abs exert only direct and not immune-mediated cytotoxic effects, the addition of rituximab and αCD20-IgG1 induced minimal or no cell killing.

Direct cytotoxic potential of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine in DLBCL and MCL cell lines and primary tumors. (A) DLBCL (RCK8) and MCL (Mino) cell lines sensitive to IL-21 alone, (B) MCL cell lines (G-519, L-128, UPN-1, and Jeko-1) resistant to IL-21 alone, and (C) primary B-cells isolated from lymphoma patients were incubated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or the molar equivalent of IL-21, αCD20-IgG1, or rituximab for 72-96 hours, followed by staining with YO-PRO-1 and PI to measure cell death. Cells positive for both dyes were considered dead. Data presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05. FL, follicular lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma.

Direct cytotoxic potential of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine in DLBCL and MCL cell lines and primary tumors. (A) DLBCL (RCK8) and MCL (Mino) cell lines sensitive to IL-21 alone, (B) MCL cell lines (G-519, L-128, UPN-1, and Jeko-1) resistant to IL-21 alone, and (C) primary B-cells isolated from lymphoma patients were incubated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or the molar equivalent of IL-21, αCD20-IgG1, or rituximab for 72-96 hours, followed by staining with YO-PRO-1 and PI to measure cell death. Cells positive for both dyes were considered dead. Data presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05. FL, follicular lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma.

We next evaluated the efficacy of the fusokine in IL-21-resistant MCL cell lines, Jeko-1, G-519, L-128, and UPN-1. Notably, αCD20-IL-21 fusokine treatment resulted in significantly increased cell death of G-519, L-128, and UPN-1 cells compared with control Ab or native IL-21 (Figure 2B). These findings suggest that the increased cell death facilitated by the fusokine above the levels of IL-21-induced death is attributed to synergism achieved by simultaneous stimulation of both IL-21R and CD20, or the more efficient targeting of IL-21 to the tumor cell surface by the Ab.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induces cell death of primary B-cell lymphomas

To demonstrate that the antitumor activity of the fusokine is not restricted to established cell lines, we next examined the direct cytotoxicity of the fusokine against de novo fresh B-cell lymphoma tumor specimens. Cell death induced by the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine was markedly increased in primary MCL (n = 2 of 3), marginal zone lymphoma (n = 2), and follicular lymphoma (n = 1) tumors compared with parent Ab or rituximab alone (Figure 2C). Primary tumors that were resistant to native IL-21 treatment also exhibited increased cell death on treatment with the fusokine. Furthermore, the cell death induced by the fusokine was higher in 5 of the 6 tested primary tumors in comparison with combination of IL-21 with parent αCD20-IgG1 Ab, suggesting superior cytotoxic efficacy of the fusokine. Of note, similar to our previous observations with IL-21,35 in vitro treatment with the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine did not induce apoptosis of normal B-cell (supplemental Figure 3B).

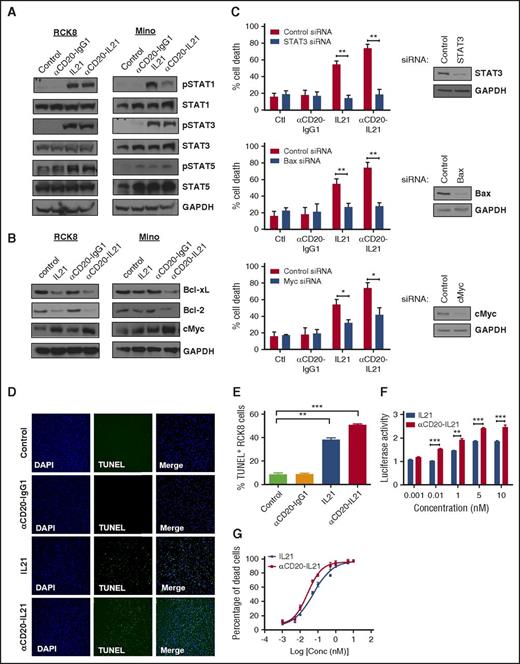

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine is more potent than native IL-21

We hypothesized that the increased cytotoxic potential of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine may be attributed to stronger activation of the IL-21R downstream signaling pathway. We have previously demonstrated that IL-21-induced apoptosis is dependent on STAT3, cMYC, and Bax, and is independent of STAT1 in DLBCL and MCL cell lines.32,35 Treatment with αCD20-IL-21 fusokine resulted in upregulation of pSTAT1, pSTAT3, and pSTAT5, similar to IL-21 alone, and was not observed in cells treated with the parent αCD20-IgG1 Ab (Figure 3A). Furthermore, we also found upregulation in cMyc, BAX, and downregulation of the antiapoptotic proteins BCL-xL and Bcl-2, which was more pronounced in the fusokine-treated cells compared with native IL-21 (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4A). To further evaluate the potential contribution of STAT-3, BAX, and cMyc to fusokine-induced cell death, we performed knockdown of these proteins using specific siRNAs. As previously reported,32,35 inhibition of STAT-3 completely abrogated IL-21-induced cell death. Although fusokine treatment led to more pronounced death than IL-21, STAT-3 inhibition still completely blocked fusokine-induced cell death, as opposed to control siRNA (Figure 3C). Similar observations were made with inhibition of BAX, whereas knockdown of cMyc led to partial but statistically significant decrease in fusokine-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 3C). Collectively, these data suggest that upregulation of pSTAT3, BAX, and cMyc is imperative for the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine-induced cell death effects.

Analysis of bioactivity and mechanisms of direct apoptosis of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. For A and B, cells were treated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 and immunoblotted with indicated Abs. (C) RCK8 cells were first transfected with siRNA targeting STAT3, Bax, cMyc, or control siRNA, followed by treatment with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 at 24 hours after transfection. Percentage of cell death was determined by YO-PRO/PI staining at 72 hours posttreatment, using flow cytometry. Immunoblotting was carried out at 24 hours posttransfection to confirm proteins knockdown. (D) RCK8 cells treated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 were subjected to TUNEL assay via immunofluorescence or (E) flow cytometry. Blue represents DAPI staining and green TUNEL staining; magnification, 20×. TUNEL positivity is indicative of fragmented DNA, a characteristic of apoptotic cells. (F) RCK8 cells were cotransfected with STAT3 luciferase reporter plasmid (pLucTKS3) and internal control plasmid (pRL-TK). At 24 hours posttransfection, cells were exposed to αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 for 48 hours, followed by dual luciferase measurements using luminometer. Data represents the luciferase activity normalized to pRL-TK signal. (G) RCK8 cells exposed to αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 were stained with YO-PRO-1/PI to measure cell death. EC50 curves were derived by plotting percentage of dead cells, using Prism software. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Analysis of bioactivity and mechanisms of direct apoptosis of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. For A and B, cells were treated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 and immunoblotted with indicated Abs. (C) RCK8 cells were first transfected with siRNA targeting STAT3, Bax, cMyc, or control siRNA, followed by treatment with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 at 24 hours after transfection. Percentage of cell death was determined by YO-PRO/PI staining at 72 hours posttreatment, using flow cytometry. Immunoblotting was carried out at 24 hours posttransfection to confirm proteins knockdown. (D) RCK8 cells treated with αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL) or equimolar doses of IL-21 or αCD20-IgG1 were subjected to TUNEL assay via immunofluorescence or (E) flow cytometry. Blue represents DAPI staining and green TUNEL staining; magnification, 20×. TUNEL positivity is indicative of fragmented DNA, a characteristic of apoptotic cells. (F) RCK8 cells were cotransfected with STAT3 luciferase reporter plasmid (pLucTKS3) and internal control plasmid (pRL-TK). At 24 hours posttransfection, cells were exposed to αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 for 48 hours, followed by dual luciferase measurements using luminometer. Data represents the luciferase activity normalized to pRL-TK signal. (G) RCK8 cells exposed to αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 were stained with YO-PRO-1/PI to measure cell death. EC50 curves were derived by plotting percentage of dead cells, using Prism software. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

To further elaborate the apoptotic potential of fusokine, we performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. Most of the RCK8 cells in the IL-21 and αCD20-IL-21 fusokine-treated groups were found to be TUNEL positive, as determined via immunofluorescence analysis and flow cytometry-based quantitation (Figure 3D-E). This suggested that similar to IL-21, fusokine also induces DNA fragmentation and pushes cells toward apoptosis. This was further depicted by increased levels of cleaved poly ADP-ribose polymerase and caspase-3/7 activity in the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine- and IL-21-treated RCK8 cells (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

To quantitatively determine the signaling activity of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, we used a STAT3 luciferase reporter assay, as STAT3 is the major effector of the IL-21 signaling cascade. As expected, at equimolar doses, both IL-21 and fusokine treatment resulted in increased pSTAT3, as indicated by increased luminescence in a dose-dependent manner, whereas αCD20-IgG1 Ab did not induce the reporter activity (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 5). Noticeably, the fusokine resulted in a significantly increased luciferase activity compared with IL-21 alone at the equimolar concentrations, suggesting that the fusion of IL-21 to anti-CD20 Ab may stabilize IL-21 and promote stronger receptor-mediated signaling. Concordantly, effective concentration (EC50) for fusokine-induced killing in RCK8 cells was lower (0.026 nM) compared with native IL-21 (0.054 nM) in a standard cell death assay (Figure 3G). Taken together, these data suggest augmentation of intracellular signaling and superior in vitro cytotoxic efficacy of the fusokine in comparison with IL-21.

We next examined CDC activity of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine. Treatment of CD20-expressing Raji cells with αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, rituximab and parental Ab in the presence of 10% to 30% serum resulted in similar CDC activity. Lysis was not induced when heat-inactivated serum was used, providing further evidence that the observed killing was CDC-mediated (supplemental Figure 6).

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine promotes NK cell activation and cytotoxic function

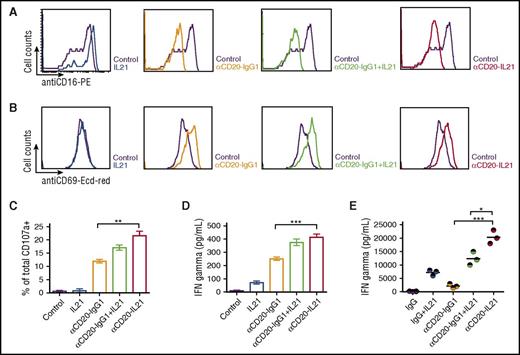

Ab-induced NK cell activation is a critical prerequisite for ADCC. Moreover, NK cells have been reported as critical mediators of IL-21-induced immune-mediated cytotoxicity.21,32 To evaluate the contribution of effector cell-mediated killing to the antitumor potential of the fusokine, we performed several functional assays for NK cells.

NK effector and Raji target cells were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio for 24 hours in the presence of IL-21, parent Ab, or fusokine to examine NK cell activation by surface FCγRIII (CD16) downregulation and CD69 upregulation, as previously reported.9 Similar downregulated expression of CD16 and upregulated expression of CD69 were observed after exposure to αCD20-IgG1, IL-21 with αCD20-IgG1, and αCD20-IL-21 fusokine (Figure 4A-B).

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induces NK-cell activation and cytotoxic function. For A-D, freshly isolated human NK cells and Raji cells were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL), or equimolar concentration of IL-21, or αCD20-IgG1. Flow cytometric analysis of NK cell activation markers (A) CD16, (B) CD69, and degranulation marker (C) CD107a is shown. (D) IFNγ levels in cell supernatant measured via ELISA. (E) Analysis of serum IFNγ levels in CD20-Tg Balb/c mice engrafted with A20-hCD20 tumors treated with αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, αCD20-IgG1, and/or IL-21 or control IgG. Each circle represents an individual mouse, with the horizontal line representing mean value. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induces NK-cell activation and cytotoxic function. For A-D, freshly isolated human NK cells and Raji cells were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of αCD20-IL-21 (1 µg/mL), or equimolar concentration of IL-21, or αCD20-IgG1. Flow cytometric analysis of NK cell activation markers (A) CD16, (B) CD69, and degranulation marker (C) CD107a is shown. (D) IFNγ levels in cell supernatant measured via ELISA. (E) Analysis of serum IFNγ levels in CD20-Tg Balb/c mice engrafted with A20-hCD20 tumors treated with αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, αCD20-IgG1, and/or IL-21 or control IgG. Each circle represents an individual mouse, with the horizontal line representing mean value. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

We next investigated the cytotoxic function of NK cells by evaluating surface expression of lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 (CD107a), a marker of lysosomal degranulation.43 Surface CD107a expression on NK cells was markedly increased after exposure to αCD20-IgG1 Ab, the combination of IL-21 with αCD20-IgG1 Ab and the fusokine, compared with IL-21 alone (Figure 4C). Further, CD107a surface expression was higher on NK cells exposed to fusokine compared with parent αCD20-IgG1 Ab alone or in combination with IL-21, but the difference was statistically significant only in comparison with the parent αCD20-IgG1 Ab alone (Figure 4C).

Having established that the cell surface expression of CD107a increases in response to fusokine stimulation, we examined the NK cell effector response by measuring IFNγ production. Significantly increased in vitro IFNγ secretion was observed in the presence of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine compared with parent Ab alone or native IL-21 that has been reported to induce IFNγ secretion.21 The combination of IL-21 with the parent Ab led to increased IFNγ secretion that was indistinguishable from the fusokine (Figure 4D). In contrast, in the in vivo A20-huCD20 tumor model, the fusokine induced significantly higher serum IFNγ concentrations in comparison with IL-21, parent Ab, or their combination (Figure 4E).

Overall, these findings suggest that although fusokine induces similar NK cell activation as the combination of IL-21 with the parent Ab in vitro, there is increased activation by the fusokine in the in vivo setting.

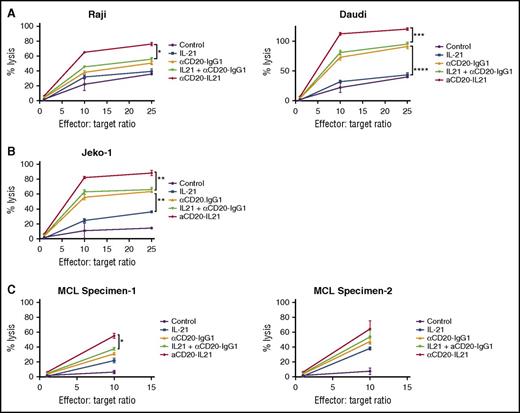

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induces FcγR-mediated cell killing of B-cell lymphoma cell lines and primary tumors

ADCC is the major mechanism of cell killing by anti-CD20 Abs.8 Given that IL-21 may augment the ADCC activity of mAbs,21 we measured the cytolytic potential of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine via chromium release assay in B-cell lymphoma cell lines. αCD20-IL-21 fusokine treatment led to a marked increase in NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity of Raji (P < .05) and Daudi (P < .001) cells, as opposed to parent Ab, native IL-21, or the combination of both in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A). Interestingly, the Jeko-1 cell line, which is resistant to the direct effects of IL-21, was also killed by fusokine-induced ADCC activity (P < .005; Figure 5B). Remarkably, fusokine-induced target cell lysis was significantly enhanced in comparison with IL-21 alone, parent Ab alone, or their combination in all analyzed cell lines. Similarly, the fusokine treatment resulted in enhanced ADCC of newly diagnosed MCL primary tumor cells in comparison with IL-21, parent Ab, or their combination (Figure 5C).

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine increases NK-cell mediated cytotoxicity of B-cell lymphomas in vitro. For A-C, human NK cells (used as effectors) isolated from peripheral blood were stimulated overnight with indicated Abs. Lymphoma cells (used as targets) were labeled with 51Cr for 2 hours, followed by coating with αCD20-IL-21 (0.01 µg/mL), or molar equivalent of the indicated proteins for 1 hour. Target cells and effector cells were then incubated for 4 hours at depicted ratios to determine release of 51Cr as a measure of percentage of cell lysis. Minimum and maximum release was determined by incubation of labeled target cells in culture media alone or media supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively. Percentage of total cell lysis was determined using (sample-spontaneous/maximal-spontaneous) × 100 formula. Data are mean ± SD between triplicate wells. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine increases NK-cell mediated cytotoxicity of B-cell lymphomas in vitro. For A-C, human NK cells (used as effectors) isolated from peripheral blood were stimulated overnight with indicated Abs. Lymphoma cells (used as targets) were labeled with 51Cr for 2 hours, followed by coating with αCD20-IL-21 (0.01 µg/mL), or molar equivalent of the indicated proteins for 1 hour. Target cells and effector cells were then incubated for 4 hours at depicted ratios to determine release of 51Cr as a measure of percentage of cell lysis. Minimum and maximum release was determined by incubation of labeled target cells in culture media alone or media supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively. Percentage of total cell lysis was determined using (sample-spontaneous/maximal-spontaneous) × 100 formula. Data are mean ± SD between triplicate wells. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

We hypothesized that the fusokine-enhanced ADCC may be attributed not only to increased NK cell activation but also to increased bridging in space between the target and effector cells. Indeed, we observed more pronounced NK-target cell synapse formation with the fusokine in comparison with the parent Ab (P < .05; supplemental Figure 7A-B).

Collectively, our data strongly suggest that, in addition to direct apoptosis, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induces enhanced indirect immune-mediated cell killing. This may give remarkable advantage to the fusokine therapy over native IL-21 or existing CD-20 Abs.

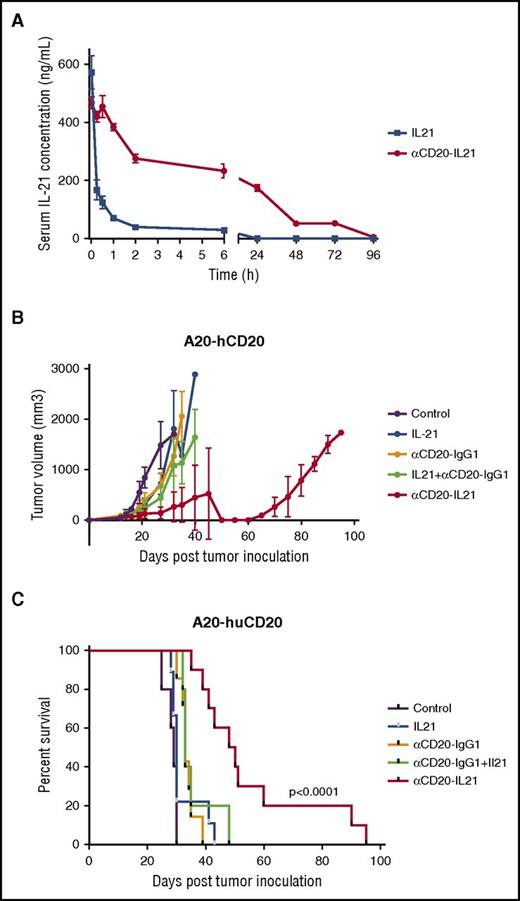

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine prolongs survival of mice with A20-hCD20 lymphoma

The cytotoxic activity of the fusokine in lymphoma cell lines and primary tumors suggests it could be useful for treatment of patients. Therefore, we measured the pharmacokinetic parameters of IL-21 after administration of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or native IL-21. A single intravenous administration of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine into CD20-Tg BALB/c mice resulted in prolonged detectability of IL-21 in the serum, with a half-life nearly 80 times longer in comparison with native IL-21 (Figure 6A; Table 1). These studies suggest that treatment with fusokine may prolong exposure to IL-21 and result in enhanced antitumor efficacy.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine extends serum half-life of IL-21 and induces tumor regression in rituximab insensitive A20-hCD20 tumor model. (A) Serum clearance of human IL-21 after intravenous injections of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 in CD20-Tg BALB/c mice was assayed by an ELISA. N = 3/group. (B and C) Tumor growth (B) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (C) of CD20-Tg mice bearing A20-hCD20 tumors treated with 2 µg/mL αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, the equivalent molar concentration of αCD20-IgG1, and/or IL-21, or PBS. N = 10/group.

αCD20-IL-21 fusokine extends serum half-life of IL-21 and induces tumor regression in rituximab insensitive A20-hCD20 tumor model. (A) Serum clearance of human IL-21 after intravenous injections of αCD20-IL-21 fusokine or IL-21 in CD20-Tg BALB/c mice was assayed by an ELISA. N = 3/group. (B and C) Tumor growth (B) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (C) of CD20-Tg mice bearing A20-hCD20 tumors treated with 2 µg/mL αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, the equivalent molar concentration of αCD20-IgG1, and/or IL-21, or PBS. N = 10/group.

Because of known cross-reactivity between human Abs and murine effector cells, as well as hIL-21 and mouse IL-21R,24,44 we proceeded with evaluating the in vivo efficacy of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine in an immunocompetent, syngeneic mouse model, permitting evaluation of potential effects of the immune system in mediating antitumor effects. We used the rituximab-resistant subcutaneous A20-hCD20 tumor model. Although these cells ectopically express physiological levels of human CD20, they are resistant to rituximab even at larger doses (150 µg; supplemental Figure 8A-B), similar to previously reported studies with A20 cells.45

CD20-Tg BALB/c mice were inoculated subcutaneously with A20-hCD20 cells, and once tumor size reached 100 mm3, treatment with daily injection of 2 µg/mL αCD20-IL-21 or equimolar doses of IL-21, parent Ab alone, or their combination was initiated and continued for 2 weeks. Treatment with αCD20-IgG1 alone or its combination with IL-21 showed a mild but statistically significant survival advantage compared with control mice (P = .005 and P = .001, respectively). However, fusokine treatment led to further and more clinically relevant delay in tumor growth and increase in overall survival compared with control (P < .0001; Figure 6B-C). Impressively, survival advantage obtained by the fusokine treatment was far greater than αCD20-IgG1 together with IL-21, or either agent alone (median survival of 33, 34, and 49 for αCD20-IgG1, αCD20-IgG1+IL-21, and αCD20-IL-21, respectively; Figure 6B-C).

Toxicology studies demonstrated that intravenous αCD20-IL-21 fusokine treatment was well tolerated. We did not detect any changes in blood cell counts, electrolytes, and kidney and liver functions (not shown). Further, extensive histological studies of normal organs did not reveal any pathological findings (supplemental Figure 9A-L).

Discussion

Although the anti-CD20 Ab rituximab has revolutionized NHL treatment, many lymphomas still remain unresponsive or eventually develop resistance to rituximab-based therapies. Here we report development of a cytokine–Ab fusion protein, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, as a strategy to overcome resistance to anti-CD20 Abs and improve the efficacy of IL-21. Consistent with this hypothesis, we demonstrate that the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine has superior antilymphoma activities compared with its individual components. Our findings suggest that together with direct apoptosis, FcR-dependent immune cell-mediated responses are major contributors to therapeutic effects of the fusokine. These results establish the rationale for potential use of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine as a novel therapy for human lymphoma.

Because of the multifunctional nature of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, the mechanism by which it inhibits tumor growth is of interest. On the basis of our studies in DLBCL and MCL, IL-21-mediated direct cell killing is STAT3-dependent.32,35 Here we confirmed that fusokine-mediated direct cell killing is also STAT-3-dependent. Therefore, we determined the bioactivity of the fusokine, using STAT3 luciferase reporter assay. Notably, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine led to stronger STAT3 activation than rIL-21 alone. This effect was not observed on stimulation with Ab alone, suggesting STAT3 activation is solely mediated via the IL-21 component. Correspondingly, in growth inhibition studies, the fusokine demonstrated lower EC50 than rIL-21. These results suggested that fusion of IL-21 to Ab stabilizes IL-21 at the cell surface, enabling enhanced and persistent IL-21 signaling. More importantly, the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine induced direct cell death of the cell lines and primary tumors resistant to IL-21 alone or in combination with parent Ab. These findings suggest that IL-21 and /or CD20 Ab-resistant or -refractory patients may potentially benefit from fusokine therapy.

Previous studies reported that co-stimulation with IL-21 enhances the efficacy of rituximab and trastuzumab in lymphoma and breast cancer cells, respectively.21 Similarly, we observed enhanced lysis of lymphoma cells by combining parent Ab with IL-21. Strikingly, treatment with αCD20-IL-21 fusokine showed even greater increase in ADCC than the combination of parent Ab and IL-21. Focusing on NK cells as a major mediator of ADCC,9,10 we demonstrated that the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine activated NK cells, as assessed by downregulation of CD16, upregulation of CD69, and increased levels of CD107a and IFN-γ.

For in vivo study, we chose the A20-hCD20 model, a syngeneic human CD20-expressing murine B-cell lymphoma grown in immunocompetent CD20-Tg Balb/c mice, as CD20 Abs and IL-21 cross-react and activate effector cells and IL-21R in mice, respectively. Use of immunocompetent mice allows recruitment of the full range of host innate and adaptive immune effector mechanisms activated by the fusokine that should contribute to lymphoma eradication.32,39 Further, this model also allows testing of the fusokine in cells resistant to rituximab therapy. In vivo treatment of mice bearing A20-hCD20 tumors with the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine resulted in significant delay in tumor growth and prolonged animal survival compared with treatment with αCD20-IgG1 alone or together with IL-21. Tumor-specific targeting of IL-21 has critically improved the action of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine, as the nontargeted administration of rIL-21 at the equimolar doses did not prolong animal survival. These results demonstrate that delivery of IL-21 via anti-CD20 directly into the tumor vicinity is superior to systemic IL-21 administration and is a viable approach to increase the therapeutic index of this potent antitumor agent. In agreement with these findings, we observed that the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine had significantly prolonged IL-21 half-life. This enhanced antilymphoma potency of the fusokine was not associated with enhanced IL-21 toxicity in studied animals.

Fusokine administration can be viewed as essentially a 2-pronged attack, whereby both CD20 and IL-21 signaling pathways can be activated to induce cooperative immune-mediated and direct tumor cell apoptosis. Ab fusion proteins have been investigated in NHLs previously, with some currently in clinical trials. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing fusion of IL-21 to a mAb and outlining the therapeutic benefit of this novel therapy for the treatment of NHL tumors. The Ab fusion therapy used here possesses several advantages compared with concomitant treatment with individual components of the fusokine.

Targeting of cytokine by conjugating it to a mAb may result in increased on-target effects, decreased off-target toxicity, and increased cytokine stability. Furthermore, the fusokine methodology may increase therapeutic efficacy by allowing synergy between FcR-independent and FcR-dependent cytotoxic mechanisms. In addition, use of the fusokine may be specifically beneficial in rituximab-refractory/resistant patients with NHL, as targeting of 2 distinct cell surface antigens would be more likely to eliminate cancer cells with preexisting CD20 epitope variants or epitope loss. As a consequence, αCD20-IL-21 fusokine has the potential to be a versatile therapeutic, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy or other immunomodulation agents. However, only future evaluation of the αCD20-IL-21 fusokine in clinical trial will establish its clinical value in patients with NHL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center flow cytometry core facility for use of their instruments.

This study was supported by the Lymphoma Research Foundation (I.S.L.), the Dwoskin Family, Recio Family, Greg Olsen, and Anthony Rizzo Family Foundations and Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Authorship

Contribution: S.B. performed most of the laboratory work, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.P., Y.Z., K.K., and H.-M.C. performed laboratory experiments; F.V. analyzed the data; J.M.T. provided reagents and useful discussions; S.-U.S. and J.D.R. provided reagents, analyzed data, and facilitated useful discussion; and I.S.L. conceptualized the idea of the study, supervised the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Izidore S. Lossos, University of Miami, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 1475 NW 12th Ave (D8-4), Miami, FL, 33136; e-mail: ilossos@med.miami.edu.

References

Author notes

S.B. and S.P. contributed equally to this work.