Key Points

GVHD mediates donor T-cell infiltration and apoptosis of the ovarian follicle cells, leading to ovarian insufficiency and infertility.

Ovarian insufficiency and infertility are independent of conditioning, and pharmacologic GVHD prophylaxis preserves fertility.

Abstract

Infertility associated with ovarian failure is a serious late complication for female survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT). Although pretransplant conditioning regimen has been appreciated as a cause of ovarian failure, increased application of reduced-intensity conditioning allowed us to revisit other factors possibly affecting ovarian function after allogeneic SCT. We have addressed whether donor T-cell-mediated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) could be causally related to female infertility in mice. Histological evaluation of the ovaries after SCT demonstrated donor T-cell infiltration in close proximity to apoptotic granulosa cells in the ovarian follicles, resulting in impaired follicular hormone production and maturation of ovarian follicles. Mating experiments showed that female recipients of allogeneic SCT deliver significantly fewer newborns than recipients of syngeneic SCT. GVHD-mediated ovary insufficiency and infertility were independent of conditioning. Pharmacologic GVHD prophylaxis protected the ovary from GVHD and preserved fertility. These results demonstrate for the first time that GVHD targets the ovary and impairs ovarian function and fertility and has important clinical implications in young female transplant recipients with nonmalignant diseases, in whom minimally toxic regimens are used.

Introduction

The number of long-term survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) increases with the expansion of donor pools and indications for SCT, as well as with the improvement of supportive care1 : 10-year survival of 2-year survivors is now 80% to 90%.2 In female long-term survivors, infertility associated with ovarian failure is a serious late complication affecting quality of life.3 The ovary is sensitive to the adverse effects of cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy.4 In particular, a pretransplant myeloablative conditioning regimen is a significant risk for ovarian failure after SCT. Nevertheless, younger age at transplant is associated with preservation of menstrual function,5,6 and frequency of pregnancy in postpubertal women after SCT is around 0.6% to 7%.7-11

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a complex, multiorgan disorder mediated by donor T cells recognizing host alloantigens after allogeneic SCT.12,13 Primary target organs of acute GVHD are the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, but the ovary has not been considered a target organ of GVHD. However, allogeneic SCT (vs autologous SCT) and GVHD are risk factors for gonadal dysfunction and female infertility.3,14 GVHD is also a risk factor for azoospermia in male patients.15 We therefore tested a hypothesis that GVHD could be causally related to ovarian failure and infertility, initially using a mouse model of SCT without conditioning to uncover pure immunologic effects on the ovary, and finally in clinically relevant mouse models of SCT after nonmyeloablative conditioning.

Materials and methods

Mice

The mouse strains used are described in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of Hokkaido University.

SCT

Female B6D2F1 mice (10 weeks old) with or without intraperitoneal injection of busulfan (BU; 12 mg/kg; Otsuka, Tokyo, Japan) and cyclophosphamide (CY; 120 mg/kg; Shionogi, Osaka, Japan) on day −7 were intravenously injected with 8 × 107 splenocytes from allogeneic B6 or syngeneic B6D2F1 donors on day 0, as previously described.16 To track the migration of donor T cells, enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) mice were used. Female BALB/c mice were injected with 8 × 106 splenocytes and 8 × 106 bone marrow cells from syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 donors after 6.5 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) on day 0. Bilateral ovaries harvested from naive BALB/c mice were transplanted under the kidney capsule on day 1. Isolation of T cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells, and depletion of T cells, were performed using the pan T-cell, CD4+ T-cell, and CD8+ T-cell isolation kits and anti-CD90-MicroBeads, respectively, and the AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and received normal chow and autoclaved hyperchlorinated water for the first 3 weeks after SCT, and filtered water thereafter. Survival after SCT was monitored daily, and the degree of clinical GVHD was assessed weekly by a scoring system that sums changes in 5 clinical parameters: weight loss, posture, activity, fur texture, and skin integrity (maximum index = 10).17

Immunosuppressants

Prednisolone (PSL; Shionogi) or diluent was administrated to the recipients by oral gavage at a dose of 10 mg/kg daily from day 0 to day +14 after SCT, and once every 3 days thereafter. Cyclosporine (CSP; Novartis, Tokyo, Japan), at a dose of 100 mg/kg/d, or tacrolimus (TAC; Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), at doses of 5 to 10 mg/kg/d, was orally administered daily from day 0 to day +20 after SCT.

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin. Next, 5-μm-thick serial sections were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Volume of unilateral ovary was calculated by length × width2 × π/6.18

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

Antigens were retrieved by heating, and sections were treated with Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan) for 30 minutes, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (Abs) at 4°C overnight. The primary Abs are provided in supplemental Table 1. Target antigens were then visualized using secondary Abs, and observed as described in supplemental Methods.

ELISA

Serum levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) were measured using an ELISA kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with sensitivity of 0.08 ng/mL.

Superovulation assay

Ovulation of the normally growing follicle of the ovary was induced by injecting 10 U pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin (PMSG; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) on day +18, followed by 10 U human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Sigma-Aldrich) 48 hours later. The ovaries, oviducts, and yolks were isolated en bloc 13 or 17 hours later, and the numbers of ovulated oocytes collected from the ampulla of oviduct were enumerated.

Mating trials

To evaluate fertility, recipient females were mated with naive B6D2F1 males of proven fertility at a 2:1 ratio repeatedly every 3 weeks from day +14 to day +100 or +150 after SCT. The numbers of offspring per litter were recorded.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Ovaries and spleens from the recipients were mechanically mashed and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. The filtered cell suspension was stained with Abs, listed in supplemental Table 1. Apoptotic cells and dead cells were labeled with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide, respectively. Intracellular granzyme B was stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti–granzyme B monoclonal Abs after permeabilization, using Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocytes isolated from ovarian follicles was performed as described in supplemental Methods. Cells were analyzed with a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences).

Culture of granulosa cells of the ovary

The granulosa cells (2 × 104) were isolated from naive B6D2F1 mice, as described in supplemental Methods, and cultured with 5 × 105 donor T cells sorted from syngeneic or allogeneic recipients on day +15 for 12 hours in M16 culture medium (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 96-well plate.

Microarray

T-cell populations in recipients’ ovaries and spleens were sorted directly to Trizol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Total RNA extracted from up to 10 000 cells was subjected to mRNA amplification and Cy3-labeled by a Low Input Quick-Amp Labeling kit (Agilent Technologies Japan, Tokyo) and hybridized on a SurePrint G3 Mouse GE microarray kit 8 × 60K (Agilent), according to the manufacturer’s procedures. Raw data obtained from SureScan Microarray Scanner (Agilent) were preprocessed, normalized, and further analyzed using Gene Spring GX software (Agilent). The analysis of variance was used for the selection of differentially expressed genes among target populations. Microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE81397).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from sorted T-cell populations and subjected to quantitative polymerase chain reaction, as described in supplemental Methods.

Statistics

Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare data, the Kaplan-Meier product limit method was used to obtain survival probability, and the log-rank test was applied to compare survival curves. All tests were performed with the statistical program Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Online supplemental material

Supplemental Figure 1 presents transcriptome analysis of donor T cells in the ovary and spleen. Supplemental Figure 2 shows GVHD-associated genes were upregulated in donor T cells in the spleen and ovary after allogeneic SCT. Supplemental Table 1 is the list of primary Abs used in immunofluorescent studies and flow cytometry.

Results

The ovary is a target organ of GVHD

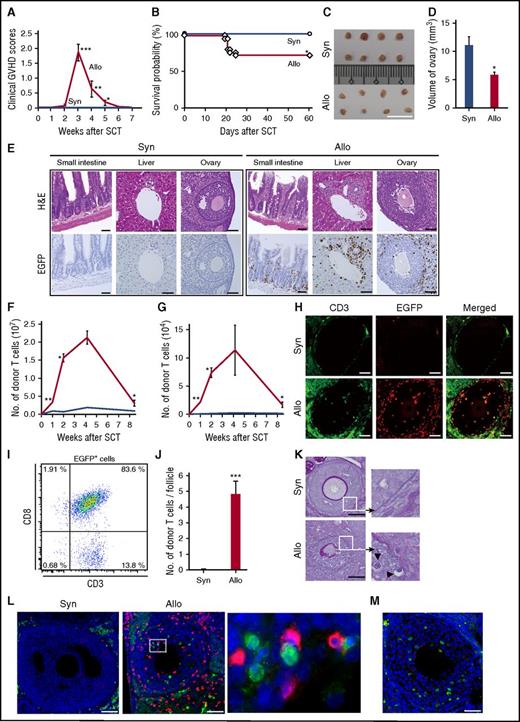

To avoid too-toxic effects of conditioning to mask other potential risks for posttransplant ovarian insufficiency, we first tested our hypothesis in a well-established parent-into-F1 model of graft-versus-host reaction without conditioning.19,20 Unirradiated B6D2F1 (H-2b/d) female mice were intravenously injected with 8 × 107 splenocytes from syngeneic or major histocompatibility complex–mismatched B6 (H-2b) donors on day 0. Allogeneic animals showed significant signs of clinical GVHD, as assessed by clinical GVHD scores (Figure 1A).17 GVHD severity peaked at 3 weeks after SCT and gradually mitigated thereafter, as previously demonstrated in this model.16,19,21 GVHD mortality was 27%, whereas all syngeneic controls survived (Figure 1B). Donor cell chimerism was more than 90% on day +14 posttransplant, as previously reported.16 Surprisingly, the ovaries were atrophic 35 days after allogeneic SCT (Figure 1C), and the estimated volumes of ovaries in allogeneic animals were significantly less than those in syngeneic controls (Figure 1D), suggesting that ovary was targeted by graft-versus-host reaction. These results urged us to perform pathological analysis of the ovary after SCT, using EGFP-expressing mice.

Donor T-cell infiltration and ovary injury after allogeneic SCT. (A-D) Unirradiated B6D2F1 female mice were intravenously injected with 8 × 107 splenocytes from syngeneic (Syn; n = 25) or allogeneic (Allo; n = 26) B6 donors. Clinical GVHD scores (means ± SE; A) and survivals (B) are shown. (C-D) Macroscopic images of the ovaries (C) and estimated ovarian volumes (D) on day +35 after SCT are shown (n = 8/group). (E-L) Unirradiated B6 (syngeneic) or B6D2F1 (allogeneic) mice were injected with 3 × 107 purified EGFP+ T cells and 5 × 107 wild-type B6 TCD. (E) The small intestine, liver, and ovary harvested on day +14 were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; upper) and EGFP (lower; brown). Original magnification ×20. (F-G) Donor T cells infiltrated in the livers (F) and ovaries (G) were enumerated by flow cytometry and shown as means ± SE (n = 3-5/group). (H) Double-label immunofluorescent staining with CD3 (green) and EGFP (red) of the ovary. (I) Representative dot plot of EGFP+ cells from ovarian follicles (n = 5). (J) EGFP+ CD3+ T cells per an ovarian follicle were enumerated on the ovarian sections (n = 6/group). (K) PAS staining. Areas in the white squares are magnified and shown in the right side of original images. Arrowheads indicate infiltrating lymphocytes beyond the disrupted basement membranes of the ovarian follicles. (L) Immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase 3 (green) and EGFP (red). Area in the white rectangle is magnified and shown in the right side of original image. Original magnification ×40. Data are representative of 2 similar experiments and shown as means ± SE. (M) Unirradiated B6D2F1 mice were injected with 3 × 107 purified T cells from wild-type B6 plus 5 × 107 TCD splenocytes from EGFP+ mice. Double-label immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase3 (green) and EGFP (red) with counter staining with DAPI (blue) is shown. Scale bar, 1 cm (C), 50 µm (E, H, K, L, and M). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

Donor T-cell infiltration and ovary injury after allogeneic SCT. (A-D) Unirradiated B6D2F1 female mice were intravenously injected with 8 × 107 splenocytes from syngeneic (Syn; n = 25) or allogeneic (Allo; n = 26) B6 donors. Clinical GVHD scores (means ± SE; A) and survivals (B) are shown. (C-D) Macroscopic images of the ovaries (C) and estimated ovarian volumes (D) on day +35 after SCT are shown (n = 8/group). (E-L) Unirradiated B6 (syngeneic) or B6D2F1 (allogeneic) mice were injected with 3 × 107 purified EGFP+ T cells and 5 × 107 wild-type B6 TCD. (E) The small intestine, liver, and ovary harvested on day +14 were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; upper) and EGFP (lower; brown). Original magnification ×20. (F-G) Donor T cells infiltrated in the livers (F) and ovaries (G) were enumerated by flow cytometry and shown as means ± SE (n = 3-5/group). (H) Double-label immunofluorescent staining with CD3 (green) and EGFP (red) of the ovary. (I) Representative dot plot of EGFP+ cells from ovarian follicles (n = 5). (J) EGFP+ CD3+ T cells per an ovarian follicle were enumerated on the ovarian sections (n = 6/group). (K) PAS staining. Areas in the white squares are magnified and shown in the right side of original images. Arrowheads indicate infiltrating lymphocytes beyond the disrupted basement membranes of the ovarian follicles. (L) Immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase 3 (green) and EGFP (red). Area in the white rectangle is magnified and shown in the right side of original image. Original magnification ×40. Data are representative of 2 similar experiments and shown as means ± SE. (M) Unirradiated B6D2F1 mice were injected with 3 × 107 purified T cells from wild-type B6 plus 5 × 107 TCD splenocytes from EGFP+ mice. Double-label immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase3 (green) and EGFP (red) with counter staining with DAPI (blue) is shown. Scale bar, 1 cm (C), 50 µm (E, H, K, L, and M). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

B6D2F1 mice were injected with EGFP+ B6 T cells and wild-type B6 T-cell depleted (TCD) splenocytes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the small intestine and liver on day +14 showed classical acute GVHD pathology (Figure 1E, upper), with infiltration of EGFP+ donor cells in immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1E, lower). In the ovary, dense infiltration of mononuclear cells and apoptotic ovarian cells was observed. Flow cytometric analysis showed that donor T-cell infiltration peaked at 4 weeks after SCT and declined thereafter, both in the liver and ovary (Figure 1F-G). Double immunofluorescent staining for EGFP and CD3 confirmed infiltration of EGFP+ CD3+ donor T cells into the ovarian follicles (Figure 1H). Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocytes isolated from the allogeneic ovarian follicles demonstrated that 97.5 ± 0.66% of EGFP+ cells infiltrating ovarian follicles were CD3+ T cells (Figure 1I). The numbers of EGFP+ CD3+ T cells per follicle were significantly greater in allogeneic animals than in syngeneic controls (Figure 1J). PAS staining of the samples showed disruption of PAS+ basement membranes of the ovarian follicles and cellular infiltration into the follicle beyond damaged basement membranes (Figure 1K). Double immunofluorescent staining for EGFP and cleaved-caspase 3 showed that cleaved-caspase 3+ apoptotic granulosa cells were neighbored by donor-derived EGFP+ T cells, a phenomenon called “satellitosis,” a hallmark of acute GVHD pathology (Figure 1L).22 When mice were injected with EGFP− allogeneic wild-type T cells plus EGFP+ TCD splenocytes, there was no infiltration of EGFP+ cells in the ovarian follicles despite of the presence of cleaved-caspase 3+ apoptotic granulosa cells, further suggesting a critical role of donor T cells in ovary GVHD (Figure 1M). Such pathological changes were not observed in syngeneic controls (Figure 1E-L).

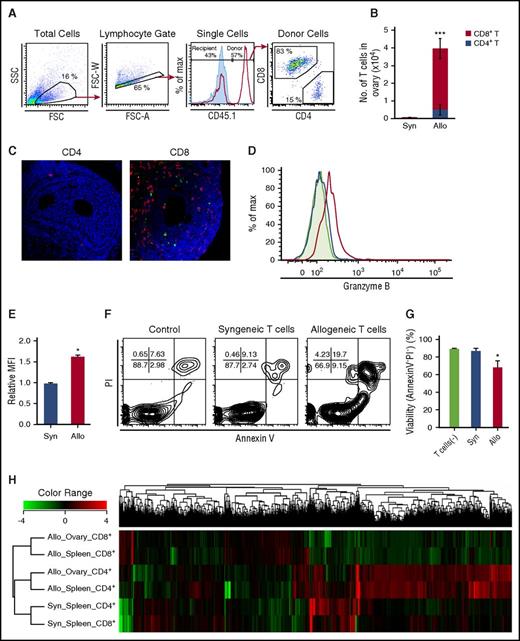

Flow cytometric analysis on day +14 after SCT from B6-CD45.1 donors confirmed infiltration of CD45.1+ donor-derived CD8+ T cells in the ovaries of allogeneic animals, but not in those of syngeneic controls (Figure 2A-B). Adoptive transfer experiments of either EGFP+ CD4+ or CD8+ T cells also demonstrated that EGFP+ donor T-cell infiltration and apoptosis of granulosa cells were observed only when CD8+ T cells were injected (Figure 2C). CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleens 15 days after allogeneic SCT exhibited features of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-expressing granzyme B (Figure 2D-E). When purified granulosa cells from naive B6D2F1 mice were cultured with these CD8+ T cells for 12 hours, significant apoptosis of granulosa cells was induced, suggesting that granulosa cells of ovarian follicles are susceptible to CTL lysis (Figure 2F-G). Because culture supernatant from allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction did not induce apoptosis of granulosa cells (data not shown), donor CD8+ chiefly confers cytotoxicity in a cel–cell contact-dependent fashion.

The profiles of T cells in the ovaries. (A-B) CD45.1+ B6 splenocytes (8 × 107) were transplanted into unirradiated allogeneic B6D2F1 (CD45.2+) or congenic B6 (CD45.2+) mice on day 0. Ovaries are harvested on day +14 after SCT for flow cytometric analysis. (A) Panels show the gating strategies of donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the histogram shows detection of donor cells in allogeneic (red line) and syngeneic (blue shaded) hosts. (B) Numbers of donor T cells in the ovaries in syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 10) mice were shown as mean ± SE. (C) Mice were injected with either 3 × 107 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from EGFP+ mice. Double-label immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase 3 (green) and EGFP (red) of the ovary on day +14. Original magnification ×40. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D-G) Isolated granulosa cells (2 × 104) from the B6D2F1 ovaries were cultured alone (n = 3) or in the presence of 5 × 105 donor T cells sorted from syngeneic (n = 3) or allogeneic recipients (n = 4) on day +15 for 12 hours. Max, maximum. Representative histograms (D) and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of granzyme B expression (E) in syngeneic (blue line and bar) or allogeneic (red line and bar) CD8+ T cells and isotype controls (shaded area in histogram). Representative FACS plot of PI and Annexin V labeling in CD4−CD8− granulosa cells (F) and proportion of AnnexinV− PI− in granulosa cells (G) are shown as mean ± SE. Data from a representative of 2 similar experiments are shown. (H) Transcriptome of donor T cells isolated from syngeneic spleens (n = 2-3), allogeneic spleens (n = 2-3), and allogeneic ovarian follicles (n = 2-4) on day +14 was analyzed. Results of a hierarchical clustering analysis on differentially expressed genes are shown. *P < .05, ***P < .005.

The profiles of T cells in the ovaries. (A-B) CD45.1+ B6 splenocytes (8 × 107) were transplanted into unirradiated allogeneic B6D2F1 (CD45.2+) or congenic B6 (CD45.2+) mice on day 0. Ovaries are harvested on day +14 after SCT for flow cytometric analysis. (A) Panels show the gating strategies of donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the histogram shows detection of donor cells in allogeneic (red line) and syngeneic (blue shaded) hosts. (B) Numbers of donor T cells in the ovaries in syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 10) mice were shown as mean ± SE. (C) Mice were injected with either 3 × 107 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from EGFP+ mice. Double-label immunofluorescent staining with cleaved-caspase 3 (green) and EGFP (red) of the ovary on day +14. Original magnification ×40. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D-G) Isolated granulosa cells (2 × 104) from the B6D2F1 ovaries were cultured alone (n = 3) or in the presence of 5 × 105 donor T cells sorted from syngeneic (n = 3) or allogeneic recipients (n = 4) on day +15 for 12 hours. Max, maximum. Representative histograms (D) and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of granzyme B expression (E) in syngeneic (blue line and bar) or allogeneic (red line and bar) CD8+ T cells and isotype controls (shaded area in histogram). Representative FACS plot of PI and Annexin V labeling in CD4−CD8− granulosa cells (F) and proportion of AnnexinV− PI− in granulosa cells (G) are shown as mean ± SE. Data from a representative of 2 similar experiments are shown. (H) Transcriptome of donor T cells isolated from syngeneic spleens (n = 2-3), allogeneic spleens (n = 2-3), and allogeneic ovarian follicles (n = 2-4) on day +14 was analyzed. Results of a hierarchical clustering analysis on differentially expressed genes are shown. *P < .05, ***P < .005.

To analyze the profile of the infiltrating donor T cells in the ovaries, transcriptome profiles of donor T cells sorted from the ovaries and spleens were compared. Hierarchical clustering of all the genes differentially expressed among T-cell subsets revealed that allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were separately clustered, regardless of type of organs (Figure 2H). Principal component analysis among T-cell subsets confirmed separation between syngeneic and allogeneic cells, and between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, but overlap between the spleen and ovary (supplemental Figure 1A). Given the predominant role of donor CD8+ T cells compared with CD4+ T cells in ovarian GVHD, we identified 1721 genes upregulated in CD8+ T cells in allogeneic ovaries compared with syngeneic spleens, using an analysis of variance (supplemental Figure 1B). Among these, 27 pathways were significantly enriched in CD8+ T cells from the allogeneic ovary after assignment of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways of these genes, using the DAVID database (supplemental Figure 1C). Among 166 genes and 301 genes that were significantly upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in allogeneic ovaries compared with allogeneic spleens (supplemental Figure 1B), only 35 genes were found specifically upregulated or downregulated in ovarian GVHD after the multiple testing correction with Storey’s adjustment (supplemental Figure 1D-E). In contrast, no gene was differentially expressed in CD4+ T cells between allogeneic ovaries and spleens (supplemental Figure 1D). Altogether, transcriptomes largely overlap between the ovarian and splenic T cells from allogeneic animals, including upregulation of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines such as interferon γ, interleukin 21 (IL-21), IL-6, and colony-stimulating factor 2; genes encoding cytotoxic molecules such as FasL, granzyme A, granzyme B, and perforin; genes encoding GVHD-associated transcription factors such as AURKA and Tbet; genes encoding co-inhibitory molecules CTLA4, PD1, LAG3, TIM3 (Havcr2), and TIGIT; and genes encoding GVHD-associated chemokines such as CCR2, CCR5, CXCR3, and CX3CR1 (supplemental Figure 2A), in addition to 35 ovarian GVHD-specific genes in CD8+ T cells (supplemental Figure 1E). Among these 35 genes differentially expressed in allogeneic ovary compared with allogeneic spleens, we validated expression levels of Ccl17 and Glis1 by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Consistent with microarray data, Ccl17 expression was significantly higher and Glis1 expression significantly lower in allogeneic ovary compared with allogeneic spleen (supplemental Figure 2B).

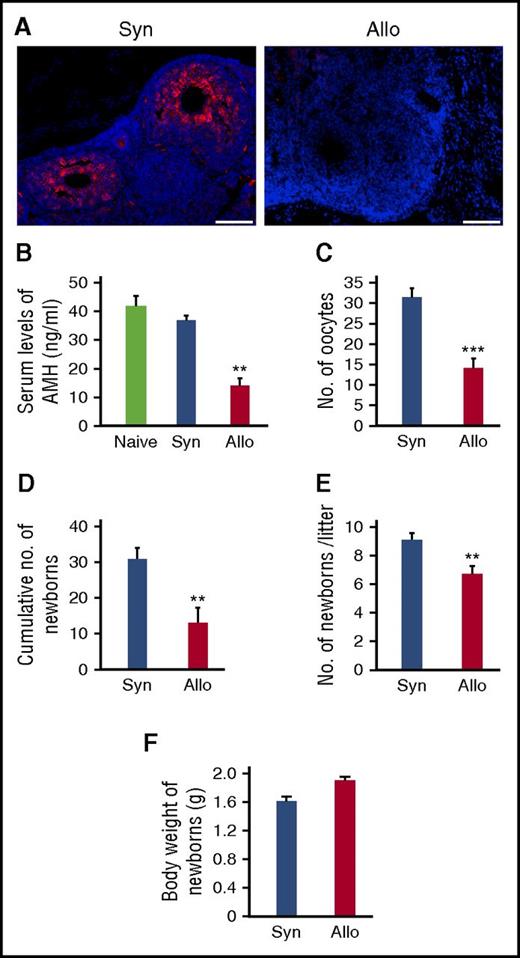

GVHD impaired ovarian functions and female fertility

We then evaluated ovary functions after SCT. Granulosa cells surrounding oocytes produce AMH, which is essential for the maintenance of ovarian follicles by inhibiting ovarian follicle exhaustion.23 Immunofluorescent staining showed that AMH expression was severely suppressed in the ovarian follicles from allogeneic animals compared with in syngeneic ovaries (Figure 3A). Serum levels of AMH, which serves as a biomarker for ovarian reserve,23 were also markedly less on day +21 in allogeneic mice than in naive and syngeneic controls (Figure 3B). To directly measure the size of the ovarian reserve, mice were injected with gonadotropins to induce ovulation, the event of releasing fully mature oocytes from the ovary. The numbers of ovulated oocytes collected from the ampulla of oviduct were significantly less in allogeneic animals compared with in syngeneic controls 3 weeks after SCT (Figure 3C).

Impaired ovary functions and fertility in GVHD. Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D. (A) Immunofluorescent staining for AMH (red) with DAPI (blue) counter staining. Original magnification ×20. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Serum levels of AMH of naive (n = 6), syngeneic (n = 6), and allogeneic (n = 13) recipients on day +21 were shown as means ± SE. (C) Numbers of oocytes ovulated on stimulation with PMSG and hCG. Data from a representative of 2 similar experiments are shown as means ± SE. (D-F) Syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 9) recipients were mated with naive males repeatedly from day +14 to day +100 after SCT. Total numbers of newborns delivered by day +100 (D), numbers of newborns per litter (E), and body weight of newborns (F) are shown as means ± SE. **P < .01, ***P < .005.

Impaired ovary functions and fertility in GVHD. Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D. (A) Immunofluorescent staining for AMH (red) with DAPI (blue) counter staining. Original magnification ×20. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Serum levels of AMH of naive (n = 6), syngeneic (n = 6), and allogeneic (n = 13) recipients on day +21 were shown as means ± SE. (C) Numbers of oocytes ovulated on stimulation with PMSG and hCG. Data from a representative of 2 similar experiments are shown as means ± SE. (D-F) Syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 9) recipients were mated with naive males repeatedly from day +14 to day +100 after SCT. Total numbers of newborns delivered by day +100 (D), numbers of newborns per litter (E), and body weight of newborns (F) are shown as means ± SE. **P < .01, ***P < .005.

To directly assess fertility, female SCT recipients were mated with healthy males repeatedly from day +14 to day +100 after SCT. Total numbers of newborns delivered over the course of the mating trial were significantly less after allogeneic SCT than after syngeneic SCT (Figure 3D). Numbers of newborns per litter were also significantly reduced after allogeneic SCT than after syngeneic SCT (Figure 3E). However, weights of newborns were comparable between the 2 groups without any developmental defects (Figure 3F).

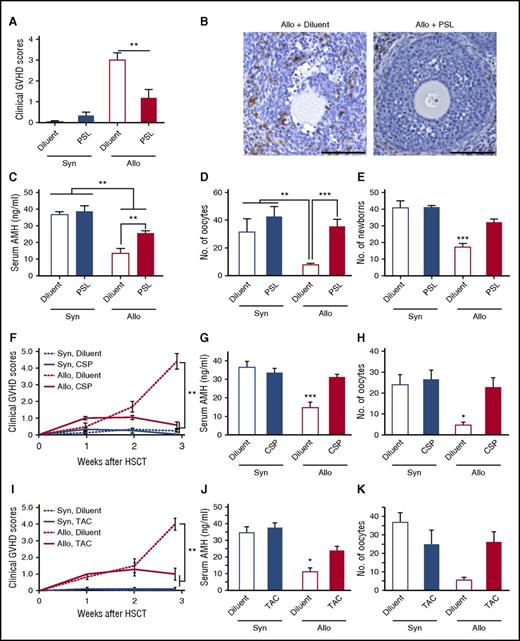

GVHD prophylaxis protected the ovary and preserved female fertility

Next, we tested whether pharmacological GVHD prophylaxis could protect the ovary from GVHD and preserve female fertility after allogeneic SCT. To test this hypothesis, 10 mg/kg PSL was orally administered from day 0 to day +20. PSL significantly reduced GVHD severity (Figure 4A), inhibited donor T-cell infiltration and GVHD pathology in the ovary (Figure 4B), and maintained serum AMH levels (Figure 4C) and maturation of the follicles (Figure 4D). Importantly, PSL preserved fertility, as determined by the cumulative number of newborns delivered by day +150 after allogenic SCT (Figure 4E). PSL had no effect on ovary functions and fertility in syngeneic controls (Figure 4C-E). Clinically relevant GVHD prophylaxis with CSP or TAC also prevented GVHD (Figure 4F,I) and maintained AMH production (Figure 4G,J) and ovulation (Figure 4H,K).

GVHD prophylaxis preserved ovarian functions and fertility. (A-D) Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D, followed by the oral administration of 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to day +20. (A) Clinical GVHD scores on day +21 of diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 13) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients are shown as mean ± SE. (B) The ovary isolated on day +14 was stained with anti-CD3 mAbs (brown). Original magnification ×20. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Serum levels of AMH in diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients, and diluent-treated (n = 13) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients, are shown as mean ± SE. (D) Numbers of oocytes ovulated on stimulation with PMSG and hCG in diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 4) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 7) and PSL-treated (n = 6) allogeneic recipients are shown as means ± SE. (E) Recipients were orally treated with 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to day +14, and thrice a week thereafter. Recipients were mated with naive B6D2F1 males repeatedly from day +14 to day +150 after SCT. Total numbers of newborns delivered by day +150 from diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 5) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 10) and PSL-treated (n = 10) allogeneic recipients. (F-H) 100 mg/kg CSP was orally given to the recipients on days 0 to +20 after SCT (n = 4-9 /group). Clinical GVHD scores (F), serum levels of AMH (G), and numbers of oocytes on ovulation induction (H) in diluent-treated (n = 7) and CSP-treated (n = 12) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 7) and CSP-treated (n = 13) allogeneic recipients from 2 independent experiments are combined and shown as means ± SE. (I-K) 5 mg/kg TAC was orally given to the recipients on days 0 to +20 after SCT. Clinical GVHD scores (I) and serum levels of AMH (J) in diluent-treated (n = 5) and TAC-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 4) and TAC-treated (n = 6) allogeneic recipients are shown as means ± SE. (K) The numbers of oocytes on ovulation induction in diluent-treated (n = 5) and TAC-treated (n = 4) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 2) and TAC-treated (n = 4) allogeneic recipients are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

GVHD prophylaxis preserved ovarian functions and fertility. (A-D) Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D, followed by the oral administration of 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to day +20. (A) Clinical GVHD scores on day +21 of diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 13) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients are shown as mean ± SE. (B) The ovary isolated on day +14 was stained with anti-CD3 mAbs (brown). Original magnification ×20. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Serum levels of AMH in diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients, and diluent-treated (n = 13) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients, are shown as mean ± SE. (D) Numbers of oocytes ovulated on stimulation with PMSG and hCG in diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 4) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 7) and PSL-treated (n = 6) allogeneic recipients are shown as means ± SE. (E) Recipients were orally treated with 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to day +14, and thrice a week thereafter. Recipients were mated with naive B6D2F1 males repeatedly from day +14 to day +150 after SCT. Total numbers of newborns delivered by day +150 from diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 5) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 10) and PSL-treated (n = 10) allogeneic recipients. (F-H) 100 mg/kg CSP was orally given to the recipients on days 0 to +20 after SCT (n = 4-9 /group). Clinical GVHD scores (F), serum levels of AMH (G), and numbers of oocytes on ovulation induction (H) in diluent-treated (n = 7) and CSP-treated (n = 12) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 7) and CSP-treated (n = 13) allogeneic recipients from 2 independent experiments are combined and shown as means ± SE. (I-K) 5 mg/kg TAC was orally given to the recipients on days 0 to +20 after SCT. Clinical GVHD scores (I) and serum levels of AMH (J) in diluent-treated (n = 5) and TAC-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 4) and TAC-treated (n = 6) allogeneic recipients are shown as means ± SE. (K) The numbers of oocytes on ovulation induction in diluent-treated (n = 5) and TAC-treated (n = 4) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 2) and TAC-treated (n = 4) allogeneic recipients are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

Impaired ovary functions were independent of conditioning

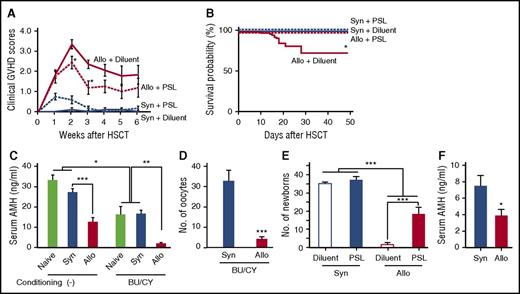

So far, our results demonstrate development of the ovarian GVHD in a mouse model of allogeneic SCT without any conditioning; however, the pretransplant conditioning regimen is indispensable in clinical SCT. We next repeated experiments in a mouse model of SCT after nonmyeloablative conditioning with BU and CY, as previously reported.24 In this model, donor chimerism was 93.3 ± 1.8% on day +17, and GVHD mortality was 24% at day +50 (Figure 5A-B). BU/CY regimen significantly reduced serum AMH levels in both naive and syngeneic mice, indicating its direct toxicity on the ovary (Figure 5C). Importantly, serum levels of AMH and the numbers of oocytes on superovulation were further reduced after allogeneic SCT after BU/CY conditioning than after syngeneic SCT (Figure 5C-D). Cumulative numbers of newborns were also markedly less after BU/CY conditioned allogeneic SCT than after syngeneic SCT (Figure 5E), demonstrating that GVHD-mediated ovary insufficiency and infertility were independent of conditioning effects on the ovary.

GVHD-mediated ovarian insufficiency after SCT after nonmyeloablative conditioning. After intraperitoneal injection of BU (12 mg/kg) and CY (120 mg/kg) on day −7, mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D. Groups of mice were orally administered with 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to +14 after SCT, and thrice a week thereafter. (A) Clinical GVHD scores of diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 12) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients. Data from 1 of 5 similar experiments were shown as means ± SE. (B) Survivals of diluent-treated (n = 30) and PSL-treated (n = 14) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 37) and PSL-treated (n = 18) allogeneic recipients were shown by combining results of 5 independent experiments. (C) Serum levels of AMH on day +21 in naive mice (n = 4) and syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 8) recipients of nonconditioned SCT and BU/CY-treated naive mice (n = 4) and syngeneic (n = 8) and allogeneic recipients of BU/CY-treated SCT were shown as means ± SE. (D) The numbers of oocytes ovulated on PMSG and hCG in syngeneic (n = 8) and allogeneic (n = 10) recipients are shown as means ± SE. (E) Mice were mated with naive male B6D2F1 mice repeatedly from day +14 to +150 and cumulated numbers of newborns from diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 8) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 11) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients were shown as means ± SE. (F) Female BALB/c mice were injected with 8 × 106 splenocytes and 8 × 106 bone marrow cells from syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 donors after 6.5 Gy TBI on day 0. Bilateral ovaries harvested from naive BALB/c mice were transplanted under the kidney capsule on day +1. Serum levels of AMH in syngeneic (n = 10) and allogeneic (n = 11) recipients on day +112 are shown as mean ± SE. Data from 2 independent experiments were combined. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

GVHD-mediated ovarian insufficiency after SCT after nonmyeloablative conditioning. After intraperitoneal injection of BU (12 mg/kg) and CY (120 mg/kg) on day −7, mice were transplanted as in Figure 1A-D. Groups of mice were orally administered with 10 mg/kg PSL daily from day 0 to +14 after SCT, and thrice a week thereafter. (A) Clinical GVHD scores of diluent-treated (n = 5) and PSL-treated (n = 6) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 12) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients. Data from 1 of 5 similar experiments were shown as means ± SE. (B) Survivals of diluent-treated (n = 30) and PSL-treated (n = 14) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 37) and PSL-treated (n = 18) allogeneic recipients were shown by combining results of 5 independent experiments. (C) Serum levels of AMH on day +21 in naive mice (n = 4) and syngeneic (n = 6) and allogeneic (n = 8) recipients of nonconditioned SCT and BU/CY-treated naive mice (n = 4) and syngeneic (n = 8) and allogeneic recipients of BU/CY-treated SCT were shown as means ± SE. (D) The numbers of oocytes ovulated on PMSG and hCG in syngeneic (n = 8) and allogeneic (n = 10) recipients are shown as means ± SE. (E) Mice were mated with naive male B6D2F1 mice repeatedly from day +14 to +150 and cumulated numbers of newborns from diluent-treated (n = 6) and PSL-treated (n = 8) syngeneic recipients and diluent-treated (n = 11) and PSL-treated (n = 8) allogeneic recipients were shown as means ± SE. (F) Female BALB/c mice were injected with 8 × 106 splenocytes and 8 × 106 bone marrow cells from syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 donors after 6.5 Gy TBI on day 0. Bilateral ovaries harvested from naive BALB/c mice were transplanted under the kidney capsule on day +1. Serum levels of AMH in syngeneic (n = 10) and allogeneic (n = 11) recipients on day +112 are shown as mean ± SE. Data from 2 independent experiments were combined. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005.

To further confirm the conditioning independency, BALB/c mice were treated with 6.5 Gy TBI, which was sufficient to cause ovary insufficiency and infertility (data not shown), and transplanted with cells from clinically relevant major histocompatibility complex–matched, minor histocompatibility antigen–mismatched B10.D2 donors. On day +1, bilateral ovaries harvested from naive BALB/c mice were transplanted under the kidney capsule of recipients. Serum levels of AMH were continuously lower in allogeneic mice compared with in syngeneic mice (Figure 5F). Thus, protection of the ovary from conditioning regimen may not be sufficient to preserve ovary functions when GVHD develops, again demonstrating the conditioning-independent ovary insufficiency mediated by GVHD.

In allogeneic SCT after BU/CY conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis with PSL significantly improved morbidity and mortality of GVHD (Figure 5A-B), and again preserved fertility after BU/CY-conditioned allogeneic SCT (Figure 5E). Collectively, these results indicate that GVHD impaired ovarian function and fertility independent of conditioning regimen, and GVHD prophylaxis can preserve fertility after allogeneic SCT after less toxic conditioning.

Discussion

Although the ovary has not been considered a target organ of GVHD, our study, for the first time to our knowledge, demonstrates several lines of evidence suggesting that the ovary is a target organ of GVHD. The pathology of the ovary with GVHD was characterized by apoptosis of granulosa cells in the ovarian follicles. Apoptotic granulosa cells were intimately surrounded by donor T cells, a phenomenon called “satellitosis,” a hallmark of acute GVHD pathology in classical target tissues.22 Granulosa cells surround the oocytes within the follicle and play a critical role in pregnancy, producing AMH, which supports maturation of the follicle.23,25 After ovulation, granulosa cells turn into lutein cells, which produce progesterone to maintain pregnancy. In GVHD, granulosa cell damage resulted in reduced production of AMH. Serum level of AMH is a proxy for the size of a follicle pool and an indicator of chemotherapy-induced ovarian follicle loss.23,26 The amount of ovulation of mature follicles in response to stimulation with gonadotropins significantly decreased after allogeneic SCT. Fertility is the ultimate measure of ovarian function: When female recipients were repeatedly mated with healthy males, cumulative numbers of newborns delivered after allogeneic SCT significantly decreased after allogeneic SCT compare with after syngeneic SCT.

It has been assumed that the ovary is a sanctuary site for alloreactive donor T cells and is protected from GVHD. However, our study shows that donor T cells disrupt the basement membrane and invade the ovarian follicles, as autoreactive T cells do in autoimmune oophoritis.27 The immunophenotypic and transcriptional profile of T cells in the ovary indicates that cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play an important role in ovary GVHD. These are highly aligned between T cells in the ovary and spleen, suggesting commonality in the mechanisms of GVHD of the ovary and other organs. Furthermore, the kinetics of donor T-cell infiltration in the ovary were synchronized with those in the liver. These data suggest that ovary GVHD is a part of systemic GVHD. However, we found that there are several genes specifically upregulated in the ovary compared with in the spleen after allogeneic SCT. Further studies are required to determine critical molecules for T-cell homing to the ovary.

Direct adverse effects of GVHD on ovarian function after allogeneic SCT have not been well documented in humans. This is largely because of the devastating effects of the conditioning regimen on ovary function, which masks other potential risk factors. In this study, we demonstrate that GVHD-mediated ovary insufficiency is independent of conditioning effects on the ovary. There are several reports suggesting a link between GVHD and ovary insufficiency. A recent study evaluating AMH levels in 6 young female long-term survivors after SCT showed that serum levels of AMH were restored in 5 patients with no or mild acute GVHD, but not in 1 patient with severe acute and chronic GVHD.28 Further studies in a larger cohort are required to clarify the association between GVHD and ovarian dysfunction. A significant reduction of ovarian volume in patients with chronic GVHD has been reported,14 and thus chronic GVHD may be also related to ovarian injury, although we did not address the effect of chronic GVHD in this study.

Our study showed that injury to the ovary microenvironment was causally related to infertility. Of note, cancer chemotherapy also damages granulosa cells, leading to insufficient production of AMH and impaired oocyte maturation,29,30 although irradiation and myeloablative conditioning also induce direct oocyte apoptosis.31 Thus, chemotherapy and GVHD may additively damage the ovarian microenvironment. Interestingly, a previous study of experimental GVHD without a conditioning regimen demonstrated histologic evidence of intratesticular infiltration of donor T cells and Leydig cell injury in the testicular microenvironment, leading to impairment of testosterone production in acute GVHD, although its effect on spermatogenesis was not addressed.32 That study showed spacial proximity of donor T cells and Leydig cells, suggesting that direct T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity could be responsible for Leydig cell injury, similar to our results. Taken together with our results, it seems that donor-derived cytotoxic T-cell-mediated injury of gonadal microenvironment is a common cause of both male and female infertility in GVHD. Several clinical studies also suggest a link between GVHD and male infertility: Sperm counts are lower in patients with GVHD than in those without it,33 and ongoing chronic GVHD and a history of prior acute GVHD are risk factors for impaired spermatogenesis.15

Young patients who underwent allogeneic SCT for nonmalignant diseases such as aplastic anemia have a greater possibility for a spontaneous recovery of menarche, gonadal recovery, and pregnancies than patients with leukemia who had been heavily treated with multiple cycles of chemotherapy before SCT and who likely received intensive pretransplant conditioning at SCT.10 Among 103 female patients with aplastic anemia who underwent SCT after CY-only conditioning, 56 (54%) recovered ovary function and 28 (27%) became pregnant.7 Among 83 pregnancies in female transplant survivors reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, 49 (59%) patients had nonmalignant diseases, including 45 (54%) patients with aplastic anemia.34 However, association between GVHD and fertility has not been well studied. In an attempt to protect the ovary from conditioning toxicity, the ovaries are shielded from TBI in some young female patients.35 However, our ovary transplant experiments after conditioning indicate that GVHD-mediated ovary insufficiency develops independent of conditioning effects on the ovary. In addition to the ovary injury in acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, involving the vulva and vagina, and mental changes could impair female fertility.36 It is also possible that donor T-cell-mediated injury of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland is associated with female infertility, as accumulating evidence suggests the central nervous system could be target of GVHD,37 although we assumed ovary injury could be the primary cause of infertility in this study because AMH secretion seems to be only marginally influenced by gonadotropins.38

Pharmacological GVHD prophylaxis protects gonadal microenvironments from donor T-cell attack, thus preventing ovarian failure and subsequent infertility. Our results thus have important clinical implications for young female transplant recipients with nonmalignant disease, in whom minimally toxic conditioning regimens are used. Although most of patients who undergo allogeneic SCT are being treated with an immunosuppressant for GVHD prophylaxis, GVHD often develops even with an immunosuppressant. In such a scenario, successful GVHD prophylaxis is critical to preserving female fertility. Our results demonstrate a previously unrecognized role of GVHD prophylaxis in female fertility. Rates of recovery of ovary function and fertility after autologous SCT are generally higher than after allogeneic SCT.39 In addition to differences in conditioning regimens, the absence of GVHD may be associated with better fertility after autologous SCT. Our results in animals deserve further clinical scrutiny, but they promise to open a new avenue for preventing infertility in SCT recipients.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lifa Lee from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yamaguchi University, and Fumio Otsuka from the Department of General Medicine, Okayama University, for expert technical assistance.

This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (15K15358 and 25670443 [T.T.], and 26461438 [D.H.]), Promotion and Standardization of the Tenure-Track System (D.H.), and research grants from Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (D.H.), Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (K.K.), Takeda Science Foundation (D.H.), and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (D.H. and K.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: T.T. developed the conceptual framework of the study, designed the experiments, conducted studies, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. S.S., D.H., K.M., and K.K. conducted experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. H.T., S.T., R.O., and T.J. conducted experiments. H.I., T.M., and K.A. supervised experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Takanori Teshima, Department of Hematology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, N14W5 Kita-ku, Sapporo 060-8648 Japan; e-mail: teshima@med.hokudai.ac.jp.