Key Points

We demonstrate an important role for NR4A receptors in regulating neutrophil lifespan and homeostasis in vitro and in vivo.

These findings may define targets for therapies for diseases driven by defects in neutrophil number and/or survival.

Abstract

The lifespan of neutrophils is plastic and highly responsive to factors that regulate cellular survival. Defects in neutrophil number and survival are common to both hematologic disorders and chronic inflammatory diseases. At sites of inflammation, neutrophils respond to multiple signals that activate protein kinase A (PKA) signaling, which positively regulates neutrophil survival. The aim of this study was to define transcriptional responses to PKA activation and to delineate the roles of these factors in neutrophil function and survival. In human neutrophil gene array studies, we show that PKA activation upregulates a significant number of apoptosis-related genes, the most highly regulated of these being NR4A2 and NR4A3. Direct PKA activation by the site-selective PKA agonist pair N6/8-AHA (8-AHA-cAMP and N6-MB-cAMP) and treatment with endogenous activators of PKA, including adenosine and prostaglandin E2, results in a profound delay of neutrophil apoptosis and concomitant upregulation of NR4A2/3 in a PKA-dependent manner. NR4A3 expression is also increased at sites of neutrophilic inflammation in a human model of intradermal inflammation. PKA activation also promotes survival of murine neutrophil progenitor cells, and small interfering RNA to NR4A2 decreases neutrophil production in this model. Antisense knockdown of NR4A2 and NR4A3 homologs in zebrafish larvae significantly reduces the absolute neutrophil number without affecting cellular migration. In summary, we show that NR4A2 and NR4A3 are components of a downstream transcriptional response to PKA activation in the neutrophil, and that they positively regulate neutrophil survival and homeostasis.

Introduction

Neutrophils are an essential component of the innate immune response and are the primary cellular response to tissue infection and inflammation. As the most abundant circulating leukocyte, neutrophils undergo spontaneous apoptosis to limit inflammation and maintain homeostasis. Ordinarily short-lived cells, inflammatory neutrophils can prolong their lifespan to maximize functional potential, such as pathogen eradication.1 As a result, neutrophils are extremely sensitive to factors that trigger cell survival and engage transcriptional and signaling pathways that allow them to rapidly respond to their environment.2 Defects in neutrophil number and survival are a common factor in hematologic conditions, including neutropenia and myeloid hyperplasia, and in chronic inflammatory diseases.3 Yet, current therapeutics for these disorders are associated with long-term side effects or do not treat the underlying cellular mechanisms. Understanding the mechanisms that underpin neutrophil survival in this context will reveal targets to which novel and highly selective therapeutic approaches can be designed.

Factors that increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels also prolong neutrophil survival.4 cAMP molecules bind to and activate protein kinase A (PKA), a ubiquitous family of kinases with multiple cellular functions, including cell survival. Conversely, PKA is inactivated by depletion of cAMP, which rapidly turns off signaling, making it a candidate for the precise regulation of neutrophil survival. Although PKA has been linked to the control of neutrophil survival, as well as the control of other key effector functions, such as adhesion, superoxide production, and matrix metalloproteinase secretion,5-8 the downstream signaling of PKA in neutrophils remains unclear. This study aimed to define transcriptional responses to PKA activation and to delineate the roles of these factors in regulating neutrophil function and survival to identify new therapeutic targets for conditions in which defects in neutrophil number and survival are a key component.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Adenosine, 8-(6-aminohexyl) aminoadenosine (8-AHA) 3′:5′-cAMP (8-AHA-cAMP), adenosine 5′-[g-thio]triphosphate tetralithium salt (ATPγs), dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP), butaprost, and LY-294002 hydrochloride were all from Sigma-Aldrich, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was derived from Escherichia coli serotype R515 (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), N6-monobutyryladenosine-3,5′-cAMP (N6-MB-cAMP), 8-bromoadenosine- 3′, 5-cyclic monophosphorothioate (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) (Biolog, Bremen, Germany), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada).

Neutrophil isolation and culture

Human neutrophils were isolated by dextran sedimentation followed by plasma-Percoll gradient centrifugation from whole blood of healthy volunteers with written informed consent and ethical approval from the South Sheffield Research Ethics Committee.9,10 In selected experiments, neutrophils and monocytes were further purified by negative magnetic selection by using either a custom mixture from StemCell Technologies containing antibodies to CD36, CD2, CD3, CD9 CD19, CD56 and glycophorin A, or the Monocyte Isolation Kit II (Miltenyl Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), respectively. Following negative selection, neutrophil and monocyte purity was >99%.

Neutrophils were suspended at 5 × 106/mL in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% low-endotoxin fetal calf serum (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) and cultured in 96-well Flexiwell plates at 37°C, 5% carbon dioxide. For hypoxic culture, an in vivo 400 Hypoxia Workstation (Ruskinn, Bridgend, United Kingdom) with a 5% carbon dioxide/balance nitrogen gas mix delivered an oxygen tension of 0.75 kPa into the chamber, which correlated with a culture media oxygen tension of 3 kPa. Media were allowed to equilibrate overnight prior to use. Freshly isolated neutrophils were designated as time 0. Agonists and/or inhibitors were added at time 0 and incubated as described. PKA was agonized by a combination of 8-AHA-cAMP (100 μM or 1 mM as indicated) and N6-MB-cAMP (100 μM or 1 mM as indicated) and collectively termed N6/8-AHA. Neutrophils treated with LY294002 or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS were preincubated for 30 or 15 minutes, respectively, prior to the addition of PKA agonists.

To create the monocyte-conditioned supernatant and to concentrate monocyte-derived factors, monocytes (2 × 106/mL) were injected into prehydrated 10-kDa dialysis cassettes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cassettes were placed inside 150-cm2 tissue culture flasks with reclosable lids (Helena Biosciences, Gateshead, United Kingdom) containing RPMI 1640 with 10% human serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 100 ng/mL LPS. Monocytes were cultured for 20 hours, during which time autocrine factors (>10 kDa) accumulated in the cassette. Monocytes were removed from the cassettes and pelleted gently from the media to generate cell-free supernatant, which was stored at −80°C.

Murine progenitor cell differentiation and culture

Murine conditionally immortalized progenitors (mCMPs, Philip Taylor, Cardiff University) expressed a hoxb8-estrogen receptor–binding domain fusion protein and were routinely passaged in the presence of β-estradiol.11 On estrogen withdrawl, mCMPs were differentiated into neutrophils in the presence of murine stem cell factor (SCF) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Briefly, mCMPs were cultured at 0.1 – 1 × 106/mL in base medium (OptiMEM [Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany]) plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (PromoCell), 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 30 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) supplemented with 10 ng/mL recombinant murine SCF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 1 μM β-estradiol. All experiments were performed with cells between passages 2 to 8. Differentiation of mCMPs to neutrophils was carried out in base medium as above, supplemented daily with 20 ng/mL recombinant murine SCF and G-CSF for 4 days.12 Hemocytometer counts and cytocentrifuge slides were made daily, and the purity of mature neutrophils on day 4 was typically >90%, as assessed by cellular morphology.

Assessment of neutrophil viability and apoptosis

Neutrophil apoptosis was measured by oil immersion light microscopy (×100 objective, Nikon Eclipse TE300, Nikon, Japan). Nuclear morphology was assessed on Giemsa-stained cytocentrifuge slides by counting >300 cells per slide.10 Apoptosis was also measured by Annexin V/ToPro-3 viability staining. In brief, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with 2.5 μl Annexin V-PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and ToPro3 iodide (1:10 000 dilution, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and samples were analyzed by using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Hemocytometer counts and flow cytometrical CountBright bead (Thermo Fisher Scientific) assays were performed to assess cell numbers and for trypan blue exclusion.

Reverse transcription PCR and qPCR

RNA was prepared from cell lysates by using TRI reagent, and complementary DNA (cDNA) was transcribed by using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was carried out by using primer-probe sets from Applied Biosystems. For normalization, β-actin (Hs99999903) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) master mix was from Eurogentec (Southampton, United Kingdom), and reactions were carried out using an ABI7900 automated TaqMan system (Applied Biosystems). Messenger RNA (mRNA) quantities were analyzed in duplicate, normalized against GAPDH or β-actin as an internal control gene and expressed in relation to mRNA from a media control sample as a calibrator. Results are expressed as relative gene expression/relative quantity with the use of the ΔΔ cycle threshold method.

RNA microarray

Neutrophil RNA extracts were produced after culturing with N6/8-AHA (1 mM), GM-CSF (100 U/mL), LPS (1 μg/mL), monocyte-conditioned media (supernatant), or in hypoxic conditions for 4 hours and converted to cDNA as described. cDNA from 5 donors was pooled prior to microarray analysis. Stimulated neutrophils were compared with unstimulated and run on Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. To detect changes in total gene expression, data were analyzed by using DAVID 6.7 Bioinformatics Resource (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

siRNA gene knockdown by Amaxa Nucleofection

Nucleofection of mCMPs was carried out by using a Nucleofector 2b device (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Lyophilized ON-TARGET plus small interfering RNA (siRNA) pools (20 μM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for NR4A2 (L-048281-01-0005), NR4A3 (L-043983-01-0005), or a nontargeting control (siScrbl) were transfected with the Amaxa Nucleofector Kit V (Thermo Fish Scientific) and program D-023. All nucleofections were carried out at room temperature and recovered in 1 mL fresh growth medium. Transfected mCMPs were subsequently differentiated as described. The efficiency of gene product knockdown was assessed by reverse transcription PCR.

Morpholino injection and zebrafish tail injury

Standard control (2.0 pM), NR4A2 morpholino (MO)13 (0.5-2.0 pM), or NR4A3-MO (0.125-0.5 pM) (5′ATGGGAAAATGACTATCACACTGCT-3′) (Genetools, Philomath, OR) were injected into Tg(mpx:GFP)i114 zebrafish embryos14 at the 1-cell stage. Embryos were injured at 3 days postfertilization by tail transection, and neutrophil recruitment and resolution at the site of injury was assayed as described.15 Embryos were imaged at low magnification on a TE- 2000U microscope (Nikon) and an Orca-AG camera (Hamamatsu, Japan) by using a 4× numerical aperture 0.1 air objective (whole body counts) with Volocity software, and neutrophil numbers were determined.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs). Data were analyzed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the appropriate posttest using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Results

Transcriptional changes in human neutrophils in response to inflammatory stimuli

Neutrophils are capable of rapid transcriptional changes that are highly tailored to environmental needs, whether these be responses to injury, inflammation, or infection.2,16,17 Identifying gene expression that is unique to individual stimuli will reveal potential therapeutic targets that modify specific elements of neutrophil function. To explore the apoptosis-related transcriptional changes that follow PKA activation, an unbiased microarray approach was taken. PKA-dependent and -independent agonists were used to identify genes that are unique to PKA signaling. Human neutrophils were cultured with a range of stimuli known to prolong neutrophil survival, reflecting both highly selective agonists (N6/8-AHA, GM-CSF, LPS) and more physiological stimuli (monocyte-conditioned supernatant and hypoxia), for 4 hours, and pooled cDNA from 5 donors was subjected to Affymetrix microarray analysis, HU133 Plus 2.0 array. The complete microarray data set (accession number GSE94923) is available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE94923). Gene expression levels were compared with media-treated populations, and a false discovery rate <10% and a greater than 2-fold change were considered significant. By using the Web-based functional analysis tool DAVID, we then asked whether differentially expressed genes were enriched in specific functional pathways. We identified Z clusters of functional terms that were statistically significant (false discovery rate <10%). Among these, the Gene Ontology term “regulation of apoptosis” (GO:004281) was significant. We then focused on the specific genes represented in this term, and presented the data to show only genes that are up- or downregulated by the PKA agonist, N6/8-AHA (Figure 1). A complete figure of all GO:004281-regulated genes and DAVID analysis files are available in supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1. Figure 1 shows a marked diversity in the regulation of apoptosis-related genes between survival stimuli. Only a single upregulated gene was common to all stimuli (PSEN1, which encodes for the γ-secretase protease complex member, presenilin-1). Five genes upregulated in common with N6/8-AHA, conditioned supernatant, GM-CSF, and LPS included the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and IL-1β. The activation of PKA by N6/8-AHA, however, also led to the initiation of a unique transcriptional apoptosis program, with the exclusive upregulation of a wide variety of genes by greater than twofold, including protein kinase C, MAPK, and NR4A. With respect to absolute transcript levels, NR4A2 and NR4A3 were the 2 most highly regulated genes following N6/8-AHA treatment. In addition, neutrophils were most transcriptionally responsive to PKA activation by N6/8-AHA compared with the other stimuli, with the expression of >70 apoptosis-related genes induced in the curated DAVID cluster. Conditioned supernatant and GM-CSF treatment upregulated a high number of common genes, including a number of cell death components, such as Bcl-xL, caspase and FADD-like apoptosis regulator, and caspases 4, 5, and 10 (supplemental Figure 1). Of all stimuli, LPS and hypoxia resulted in only a limited apoptosis-related gene expression profile.

Regulated gene clusters in stimulated neutrophils. Neutrophils were cultured for 4 hours with N6/8-AHA (1 mM) (PKA), monocyte-conditioned supernatant (SN), GM-CSF (100 U/mL], LPS (1 μg/mL), and under hypoxic conditions, after which, the RNA was analyzed by Affymetrix microarray (GeneChip HU133 Plus 2.0 array). Using the DAVID Web-based functional analysis application we identified several functional terms that were overrepresented in the list of differentially expressed genes. This figure represents the differential expression status of genes in the Gene Ontology term GO:004281 (regulation of apoptosis), which was regulated by each stimulus. Greater than twofold upregulation is indicated in red, no change is indicated in gray, and greater than twofold downregulation is indicated in green. Shown are all genes (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated by N6/8-AHA. Please refer to supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site) for DAVID analysis files and supplemental Figure 1 for a complete figure of all regulated genes within GO:004281.

Regulated gene clusters in stimulated neutrophils. Neutrophils were cultured for 4 hours with N6/8-AHA (1 mM) (PKA), monocyte-conditioned supernatant (SN), GM-CSF (100 U/mL], LPS (1 μg/mL), and under hypoxic conditions, after which, the RNA was analyzed by Affymetrix microarray (GeneChip HU133 Plus 2.0 array). Using the DAVID Web-based functional analysis application we identified several functional terms that were overrepresented in the list of differentially expressed genes. This figure represents the differential expression status of genes in the Gene Ontology term GO:004281 (regulation of apoptosis), which was regulated by each stimulus. Greater than twofold upregulation is indicated in red, no change is indicated in gray, and greater than twofold downregulation is indicated in green. Shown are all genes (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated by N6/8-AHA. Please refer to supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site) for DAVID analysis files and supplemental Figure 1 for a complete figure of all regulated genes within GO:004281.

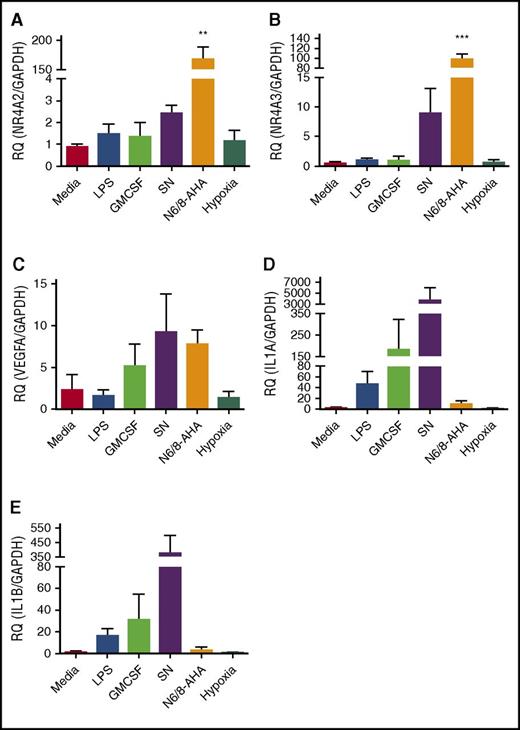

The high levels of upregulation of NR4A2 and NR4A3 seen in the array data sets were validated by qPCR. In parallel, 3 other genes associated with activation of inflammation and that showed different regulation between survival stimuli (VEGF, IL-1α, and IL-1β) were also validated by qPCR (Figure 2). NR4A2 and NR4A3 were exclusively and profoundly upregulated by N6/8-AHA treatment, linking this transcription factor family to PKA signaling in the neutrophil (Figure 2A-B). As in the microarray, specific survival factor–dependent patterns of gene expression were evident. Conditioned monocyte supernatant upregulated VEGF, IL-1α, and IL-1β (Figure 2C-E). LPS, GM-CSF, and hypoxia had limited or no effect on target gene regulation, with the exception of upregulation of IL-1α by GM-CSF (Figure 2A-E). These findings reveal that the human neutrophil is capable of generating unique transcriptional programs in response to individual inflammatory stimuli, and that PKA profoundly regulates NR4A2 and NR4A3, which have, as yet, no clear roles in neutrophil function.

qPCR validation of selected targets identified from microarray data. Ultrapurified neutrophils were stimulated with N6/8-AHA (PKA) (1 mM), monocyte-conditioned SN, GM-CSF (100 U/mL), LPS (1 μg/mL), or cultured under hypoxic conditions for 4 hours. cDNA was prepared and qPCR performed for the following genes: (A) NR4A2, (B) NR4A3, (C) VEGFA, (D) IL-1α, and (E) IL-1β. Charts show mean ± SEM and are generated from 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s posttest. Statistically significant comparisons are denoted by **P < .01 and ***P < .001, where treated populations were compared with control. RQ, relative quantity.

qPCR validation of selected targets identified from microarray data. Ultrapurified neutrophils were stimulated with N6/8-AHA (PKA) (1 mM), monocyte-conditioned SN, GM-CSF (100 U/mL), LPS (1 μg/mL), or cultured under hypoxic conditions for 4 hours. cDNA was prepared and qPCR performed for the following genes: (A) NR4A2, (B) NR4A3, (C) VEGFA, (D) IL-1α, and (E) IL-1β. Charts show mean ± SEM and are generated from 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s posttest. Statistically significant comparisons are denoted by **P < .01 and ***P < .001, where treated populations were compared with control. RQ, relative quantity.

NR4A2 and NR4A3 genes are regulated by inflammation in a PKA-dependent manner

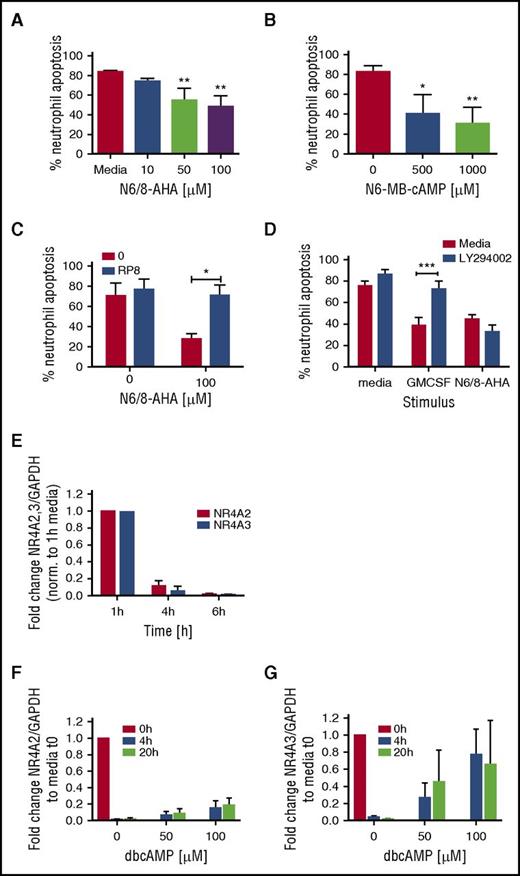

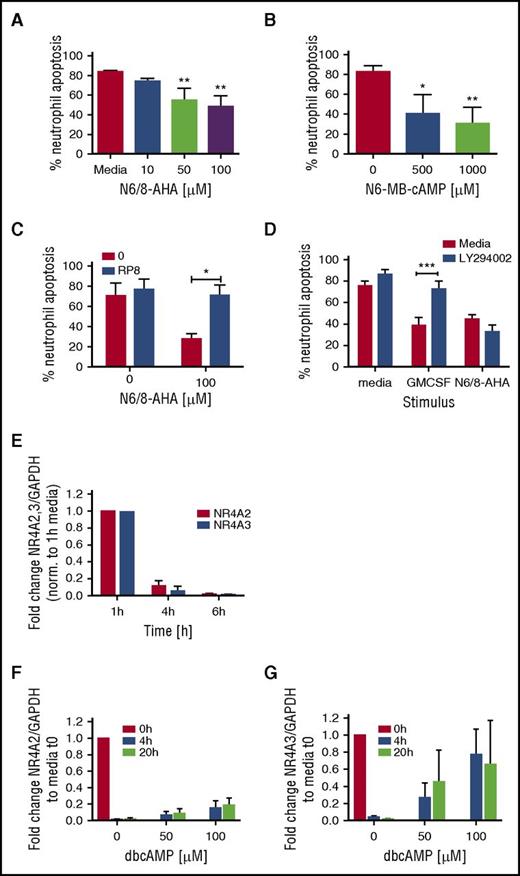

Our initial studies confirmed that PKA activation potently activated a unique survival gene expression profile. Neutrophils are the most abundant circulating leukocyte and undergo spontaneous apoptosis to both limit inflammation and maintain homeostasis. The roles of PKA activation in granulocyte survival remain incompletely understood, and limitations in the quality of functional antagonists of this pathway have hampered exploration of the relevant signaling pathways. Functional consequences of PKA signaling on neutrophil apoptosis were studied by using selective agonists of PKA. Agonizing PKA with N6/8-AHA led to a concentration-dependent decrease in neutrophil apoptosis at 20 hours (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 2A), reaching significance at 50 µM. The site-selective type IA PKA activator, N6-MB-cAMP, also significantly delayed neutrophil apoptosis at this time (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 2B). Consistent with a selective pathway regulating survival, we showed N6/8-AHA-induced neutrophil survival was reversible by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, a highly selective PKA inhibitor with no cross-reactivity for exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC) (Figure 3C), but not by the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (Figure 3D). In contrast, neutrophil survival induced by GM-CSF was prevented by LY294002. The potential relevance of NR4A transcripts was supported by these studies, because concomitant with the onset of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, both NR4A2 and NR4A3 transcripts rapidly decayed during neutrophil culture (Figure 3E), which was in part rescued by the survival factor dbcAMP for NR4A3 but not NR4A2 (Figure 3F-G).

PKA activation regulates neutrophil survival. Percoll-purified neutrophils were cultured with media or (A) N6/8-AHA at concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 or (B) N6-MB-cAMP at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μM for 20 hours. (C) Neutrophils were pretreated with media (red bars) or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) (blue bar) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of N6/8-AHA (100 μM) for an additional 20 hours. (D) Neutrophils were pretreated with media (red bars) or LY294002 (10 μM) for 30 minutes (blue bars) and cultured for an additional 20 hours with GM-CSF (50 U/mL) or N6/8-AHA (100 μM). (A-D) Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy. Charts show means ± SEMs percentage apoptosis from (C) 3, (A-B) 4, or (D) 5 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were carried out by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest and significant differences are indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001, where treated populations were compared with media control, or as indicated by lines. (E) Neutrophils were aged in culture, and RNA was isolated at time points of 1, 4, and 6 hours. In selected experiments, neutrophils were cultured with dbcAMP for 4 and 20 hours, and RNA was made at 0, 4, and 20 hours. (E-G) NR4A2/3 expression was determined by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from (E) 1-hour media or (F-G) 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control. Each panel shows data from 3 independent experiments.

PKA activation regulates neutrophil survival. Percoll-purified neutrophils were cultured with media or (A) N6/8-AHA at concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 or (B) N6-MB-cAMP at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μM for 20 hours. (C) Neutrophils were pretreated with media (red bars) or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) (blue bar) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of N6/8-AHA (100 μM) for an additional 20 hours. (D) Neutrophils were pretreated with media (red bars) or LY294002 (10 μM) for 30 minutes (blue bars) and cultured for an additional 20 hours with GM-CSF (50 U/mL) or N6/8-AHA (100 μM). (A-D) Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy. Charts show means ± SEMs percentage apoptosis from (C) 3, (A-B) 4, or (D) 5 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were carried out by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest and significant differences are indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001, where treated populations were compared with media control, or as indicated by lines. (E) Neutrophils were aged in culture, and RNA was isolated at time points of 1, 4, and 6 hours. In selected experiments, neutrophils were cultured with dbcAMP for 4 and 20 hours, and RNA was made at 0, 4, and 20 hours. (E-G) NR4A2/3 expression was determined by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from (E) 1-hour media or (F-G) 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control. Each panel shows data from 3 independent experiments.

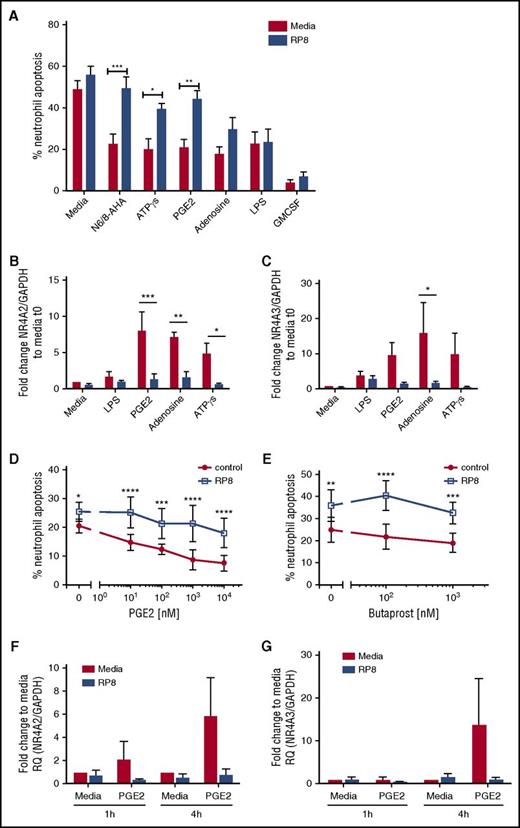

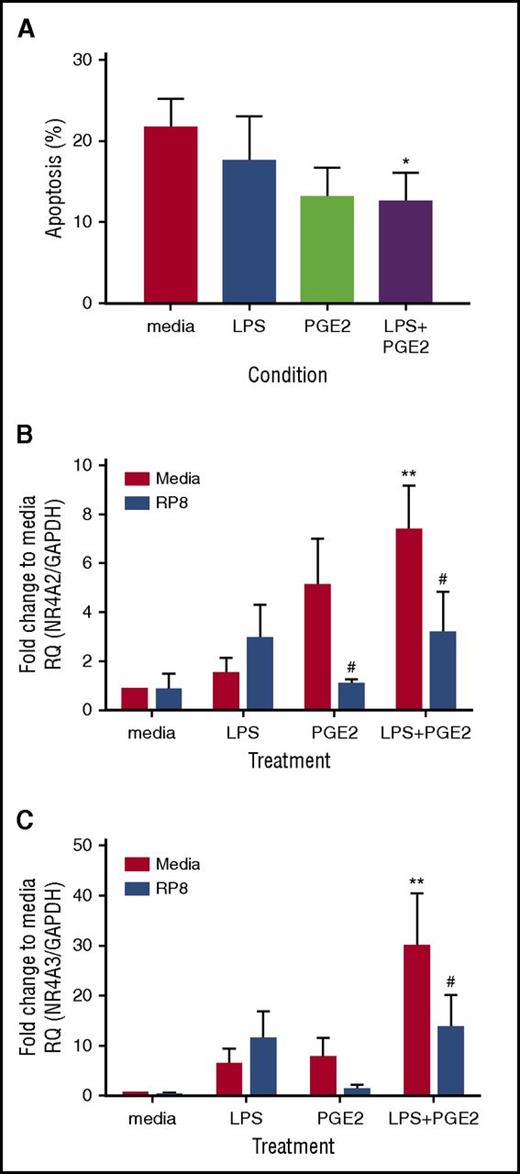

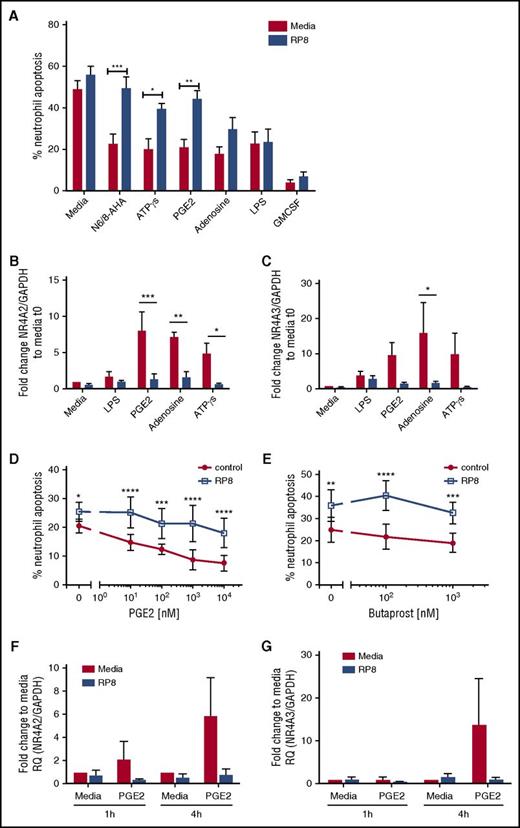

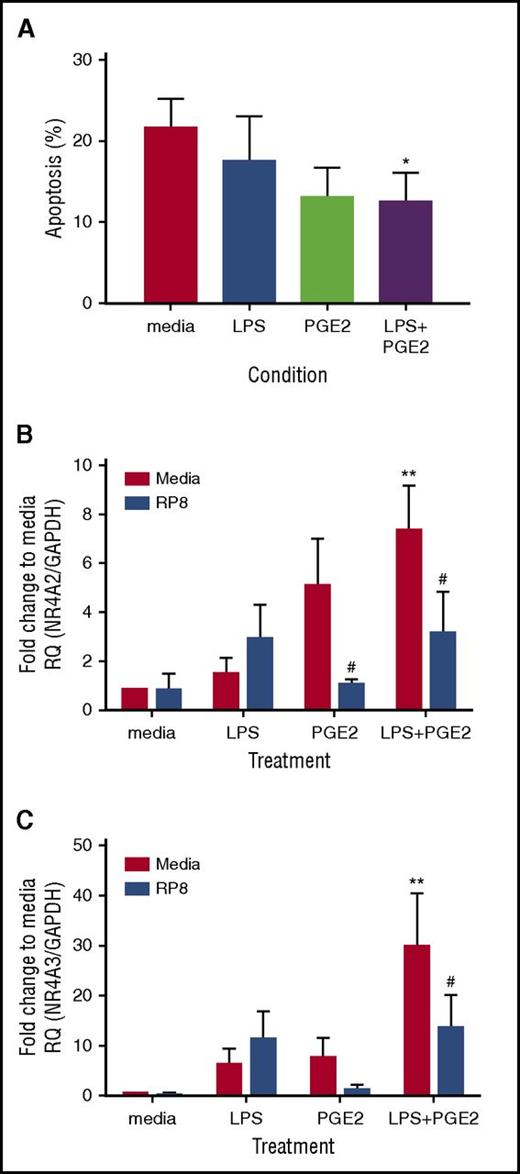

We explored whether other candidate endogenous activators of PKA signaling commonly found at sites of inflammation, including adenosine and PGE2, also caused delays in neutrophil apoptosis. Adenosine, ATPγs, and PGE2 delayed neutrophil apoptosis, and the survival effects, with the exception of adenosine, were reversed by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 2D). In contrast, LPS- and GM-CSF–induced survival was not PKA dependent (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 2D). To confirm that Rp-8-Br-cAMPS restored apoptosis rather than an alternative form of cell death, we show that the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh was able to fully reverse this effect (supplemental Figure 2B). In parallel, qPCR experiments measuring NR4A2/3 gene expression showed adenosine, ATPγs, and PGE2 upregulated NR4A2 and NR4A3 transcripts, and this upregulation was blocked by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Figure 4B-C). Modest changes in NR4A3 in response to LPS were not inhibited by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Figure 4B-C). The PGE2 and the EP2 receptor agonist butaprost delayed neutrophil apoptosis in a concentration- and PKA-dependent manner (Figure 4D-E). PGE2-mediated upregulation of NR4A2/3 was seen at 4 hours, which was fully inhibited by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Figure 4F-G). These data pointed toward NR4A2/3 expression as an important aspect of neutrophilic inflammation in vivo that could contribute to neutrophil persistence. The functional consequences of PKA signaling in vivo, where cells are also exposed to other activation signals may be different to those in vitro, as demonstrated by one study, which observed that exposure to hypoxia reduced the survival response of neutrophils to steroids.18 We therefore determined whether PKA signaling could still contribute to neutrophil survival in contexts where >1 survival stimulus is present. First, we show in an in vivo model of human intradermal endotoxin challenge that NR4A3, but not NR4A2, is upregulated greater than twofold by LPS (supplemental Figure 3), occurring at a time point that coincides with peak neutrophil recruitment19 and indicating that PKA signaling takes place in this context. To further investigate this in vitro, neutrophils were coincubated with a submaximal concentration of LPS and the physiological activator of PKA, PGE2. PGE2 remained able to significantly inhibit neutrophil apoptosis in the presence of LPS (Figure 5A) and, in parallel, a significant upregulation of NR4A2/3 was observed when both stimuli were present (Figure 5B-C). These data suggest that PKA activation is likely to lead to NR4A2/3 upregulation and neutrophil survival in complex environments consisting of multiple stimuli.

PGE2 signaling regulates neutrophil apoptosis and NR4A expression in a PKA-dependent manner. (A) Ultrapurified neutrophils were cultured in the absence (red bars) or presence (blue bars) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (RP8) (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of the following stimuli: N6/8-AHA (100 μM), PGE2 (10 μM), ATPγs [(1 μM), adenosine (100 μM), LPS (100 ng/mL), and GM-CSF (50 U/mL) for an additional 5 hours. Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs from 5 independent experiments. (B-C) In parallel experiments, neutrophils were cultured in the absence (red bars) or presence (blue bars) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of the following stimuli: LPS (100 ng/mL), PGE2 (10 μM), adenosine (100 μM), or ATPγs (1 μM) for an additional 4 hours. (B) NR4A2 and (C) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 3 independent experiments. Neutrophils were treated with media or (D) a concentration-response of PGE2 ranging from 10 nM to 10 μM or (E) butaprost (100 nM and 1 mM) in the presence (blue line) or absence (red line) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 4 hours. (D-E) Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs from 3 independent experiments. Ultrapurified neutrophils were preincubated with media or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes before the addition of media or PGE2 (10 μM) for an additional 1 or 4 hours. (F) NR4A2 and (G) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 3 independent experiments. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s or Sidak’s posttest, and statistical differences are indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001. Comparisons were made between agonist alone or agonist plus Rp-8-Br-cAMPS treated conditions for panels D and E, or as the lines indicate for the other panels.

PGE2 signaling regulates neutrophil apoptosis and NR4A expression in a PKA-dependent manner. (A) Ultrapurified neutrophils were cultured in the absence (red bars) or presence (blue bars) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (RP8) (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of the following stimuli: N6/8-AHA (100 μM), PGE2 (10 μM), ATPγs [(1 μM), adenosine (100 μM), LPS (100 ng/mL), and GM-CSF (50 U/mL) for an additional 5 hours. Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs from 5 independent experiments. (B-C) In parallel experiments, neutrophils were cultured in the absence (red bars) or presence (blue bars) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of the following stimuli: LPS (100 ng/mL), PGE2 (10 μM), adenosine (100 μM), or ATPγs (1 μM) for an additional 4 hours. (B) NR4A2 and (C) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 3 independent experiments. Neutrophils were treated with media or (D) a concentration-response of PGE2 ranging from 10 nM to 10 μM or (E) butaprost (100 nM and 1 mM) in the presence (blue line) or absence (red line) of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 4 hours. (D-E) Apoptosis was determined by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs from 3 independent experiments. Ultrapurified neutrophils were preincubated with media or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7 mM) for 30 minutes before the addition of media or PGE2 (10 μM) for an additional 1 or 4 hours. (F) NR4A2 and (G) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from 0-hour control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 3 independent experiments. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s or Sidak’s posttest, and statistical differences are indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001. Comparisons were made between agonist alone or agonist plus Rp-8-Br-cAMPS treated conditions for panels D and E, or as the lines indicate for the other panels.

PGE2 promotes neutrophil survival and increases NR4A2/3 mRNA transcripts in the presence of LPS. Ultrapurified neutrophils were treated with 1 ng/mL LPS, 10 μM PGE2, or both LPS and PGE2 together for 18 hours. (A) Apoptosis was measured by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs (n = 4). In parallel experiments, neutrophils were pretreated for 15 minutes with 0.7 mM Rp-8-Br-cAMPs (blue bars) or media (red bars) before the addition of LPS, PGE2, or both together, at the concentrations stated above for a further 4 hours. (B) NR4A2 and (C) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from media control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s posttests. Asterisks denote significant differences to the relevant media control. Pound symbols indicate differences between control and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS–treated conditions. Results were considered statistically significant at *,#P < .05 and **P < .01.

PGE2 promotes neutrophil survival and increases NR4A2/3 mRNA transcripts in the presence of LPS. Ultrapurified neutrophils were treated with 1 ng/mL LPS, 10 μM PGE2, or both LPS and PGE2 together for 18 hours. (A) Apoptosis was measured by light microscopy; data are expressed as means ± SEMs (n = 4). In parallel experiments, neutrophils were pretreated for 15 minutes with 0.7 mM Rp-8-Br-cAMPs (blue bars) or media (red bars) before the addition of LPS, PGE2, or both together, at the concentrations stated above for a further 4 hours. (B) NR4A2 and (C) NR4A3 expression was measured by qPCR. Charts show the fold change from media control, where NR4A expression was normalized to the GAPDH loading control; data are from 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s posttests. Asterisks denote significant differences to the relevant media control. Pound symbols indicate differences between control and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS–treated conditions. Results were considered statistically significant at *,#P < .05 and **P < .01.

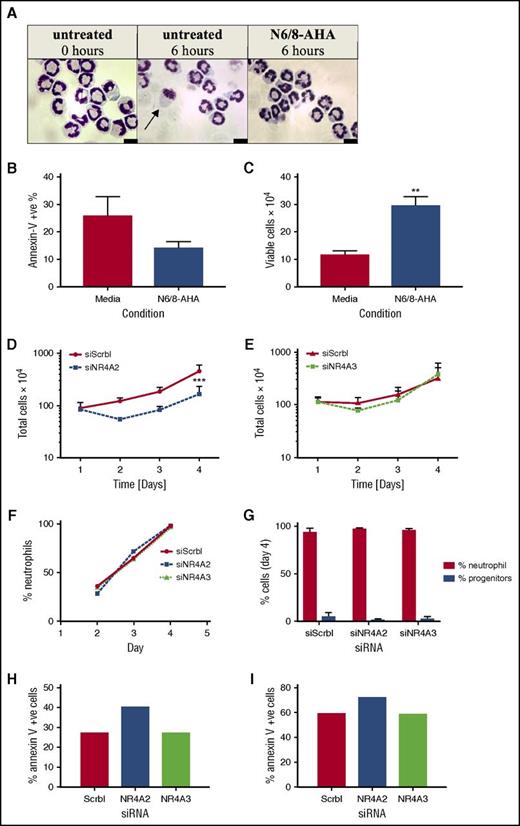

NR4A2 and NR4A3 gene deletion impedes neutrophil production

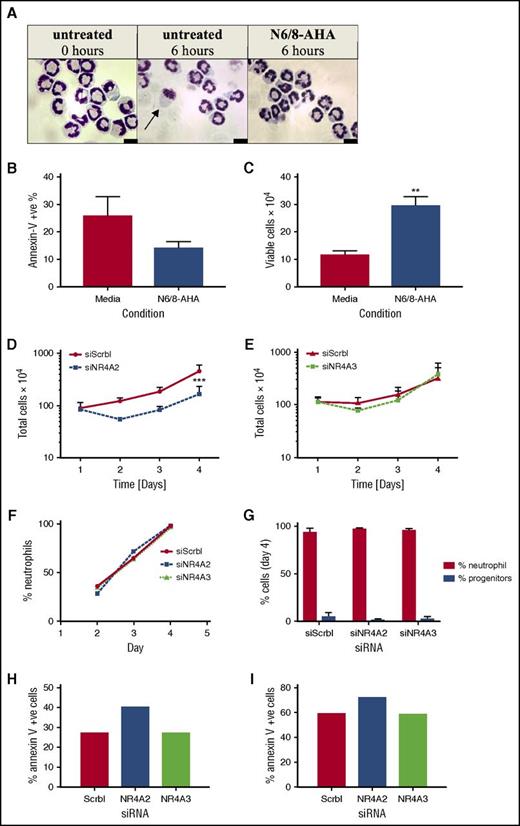

The function of NR4A in the context of neutrophil survival and inflammation was investigated by gene knockdown strategies. Because human neutrophils are genetically intractable, we adopted Hoxb8 conditionally immortalized murine myeloid progenitor cells, which allow the study of NR4A in fully functional neutrophils.11 We first confirmed the importance of PKA in survival signaling in these cells by showing a decrease in apoptosis and an increase in viable cell numbers after N6/8-AHA treatment (Figure 6A-C). Myeloid cells were transfected with NR4A2 and NR4A3 siRNA by nucleofection. Gene knockdown was verified by reverse transcription PCR, yielding an average knockdown of 90% for NR4A2 and 75% for NR4A3 (supplemental Figure 4). Cell numbers were assessed over 4 days posttransfection, and in scrambled siRNA-transfected control populations, cells proliferated by approximately fourfold by day 4 (Figure 6D-E). Knockdown of NR4A2 but not NR4A3 resulted in a reduction in cell numbers from day 2, reaching significance at day 4 (Figure 6D-E), suggesting that NR4A proteins are involved in the regulation of neutrophil survival during differentiation and neutrophil development. The increase in cell number between days 2 and 4 may reflect a gradual regeneration of NR4A transcripts and therefore restoration of survival pathways. There was no impact of NR4A2/3 knockdown on the maturation of neutrophils over time (Figure 6F) or at the end of the differentiation period (Figure 6G). NR4A2 knockdown modestly increased apoptosis of neutrophils on day 4 (Figure 6G-H).

NR4A2 siRNA knockdown inhibits myeloid cell proliferation. Hoxb8 conditionally immortalized murine myeloid progenitor cells were subjected to estrogen withdrawal and differentiated to mature neutrophils (>90% maturity) in the presence of SCF and G-CSF for 4 days with daily media replenishment. (A-C) Mature neutrophils were incubated with or without N6/8-AHA (100 μM) for 6 hours in apoptosis medium. (A) Cell viability and apoptosis was visualized by oil immersion light microscopy (arrow denotes an apoptotic cell) and (B-C) quantified by flow cytometry. RNA interference transfections were conducted 1 day after estrogen withdrawal by using Amaxa Nucleofector technology. Cells were transfected with siRNA for NR4A2, NR4A3, or a nontargeting control (siScrbl) on day 1. Total cell numbers were determined by hemocytometer counts (D-E) at days 1, 2, 3, and 4. Neutrophil maturity was assessed by light microscopy (F-G). Apoptosis was measured on (H) day 4 and (I) day 5 by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs; (B-C, G) n = 4), (D-E) n = 3, and (F, H-I) n = 1. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s posttest. Significant differences to media controls or siScrbl transfected cultures were denoted by **P <.01 or ***P < .001, respectively.

NR4A2 siRNA knockdown inhibits myeloid cell proliferation. Hoxb8 conditionally immortalized murine myeloid progenitor cells were subjected to estrogen withdrawal and differentiated to mature neutrophils (>90% maturity) in the presence of SCF and G-CSF for 4 days with daily media replenishment. (A-C) Mature neutrophils were incubated with or without N6/8-AHA (100 μM) for 6 hours in apoptosis medium. (A) Cell viability and apoptosis was visualized by oil immersion light microscopy (arrow denotes an apoptotic cell) and (B-C) quantified by flow cytometry. RNA interference transfections were conducted 1 day after estrogen withdrawal by using Amaxa Nucleofector technology. Cells were transfected with siRNA for NR4A2, NR4A3, or a nontargeting control (siScrbl) on day 1. Total cell numbers were determined by hemocytometer counts (D-E) at days 1, 2, 3, and 4. Neutrophil maturity was assessed by light microscopy (F-G). Apoptosis was measured on (H) day 4 and (I) day 5 by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as means ± SEMs; (B-C, G) n = 4), (D-E) n = 3, and (F, H-I) n = 1. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s posttest. Significant differences to media controls or siScrbl transfected cultures were denoted by **P <.01 or ***P < .001, respectively.

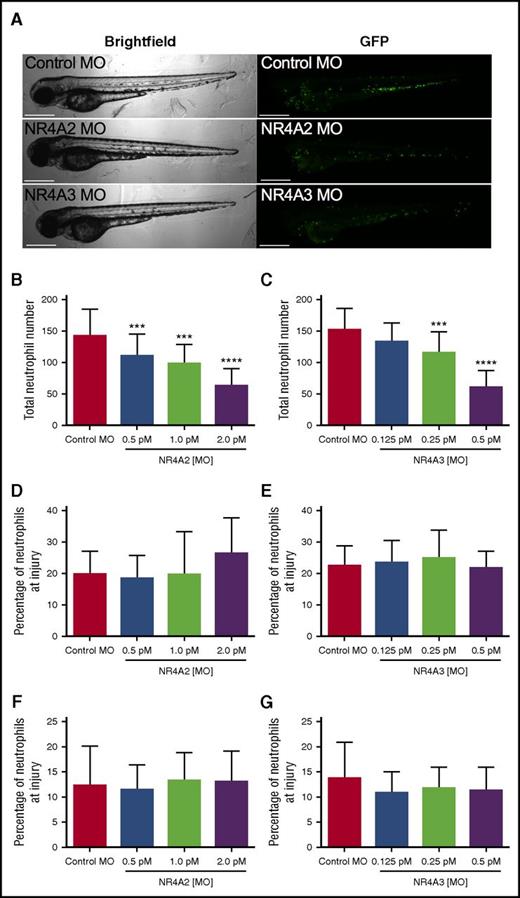

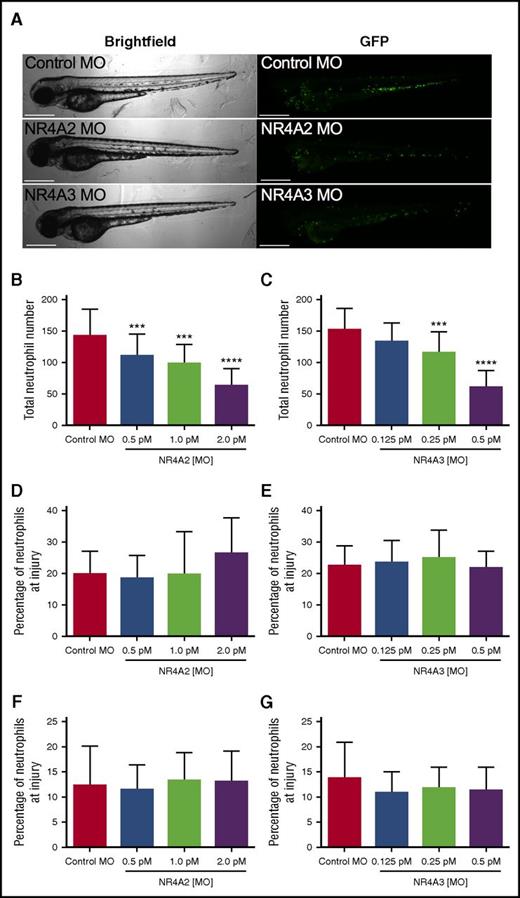

To test the possibility that NR4A2 and NR4A3 might influence developmental myelopoiesis in vivo, we used the transparent zebrafish larval model in which transgenically labeled fluorescent neutrophils can easily be visualized during development.14 To modulate expression of NR4A family members in vivo, we injected morpholino-modified antisense constructs into fertilized zebrafish eggs and observed the effect on neutrophil numbers and response to injury. Zebrafish larvae developed normally following morpholino injection (Figure 7A). Absolute numbers of neutrophils at 80 hours postfertilization (hpf) were significantly reduced at all NR4A2 morpholino concentrations used (Figure 7B) and at the 2 highest concentrations of NR4A3 morpholino used (Figure 7C). At their maximal effects, NR4A2/3 morpholinos reduce neutrophil numbers by >50% when compared with control morpholino (Figure 7B-C). To assess the effect of NR4A knockdown on neutrophil function, we used a well-established model of tissue injury initiated by tailfin transection in 3 days postfertilization larvae. To adjust for altered numbers of total neutrophils, we examined the proportion of total neutrophils recruited to the tailfin wound. In this system, neither NR4A2 or NR4A3 knockdown affected the proportion of neutrophils at the site of injury, either at 6 (Figure 7D-E) or 24 hours postinjury (Figure 7F-G), suggesting the effects on neutrophil lifespan and development are independent of the effects on neutrophil function.

NR4A2/3 regulates neutrophil number in zebrafish larvae. The mpx:GFP zebrafish larvae were injected with (A-B, D, F) NR4A2 (0.5 pM, 1 pM, or 2 pM), (A, C, E, G) NR4A3 (0.125 pM, 0.25 pM, or 0.5 pM), (A-G) or control MO (2 pM) at the 1-cell stage. (A) Neutrophils were visualized as GFP-positive events by fluorescent microscopy. (B-C) Total neutrophil numbers were assessed at 80 hpf (n = 20, performed as 3 separate experiments). Larvae were injured at 72 hpf, and neutrophil counts were performed at (D-E) 6 and (F-G) 24 hours postinjury (n = 16, performed as 2 separate experiments). Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest. Significant differences compared with control MO were denoted by ***P < .001 and ****P < .0001.

NR4A2/3 regulates neutrophil number in zebrafish larvae. The mpx:GFP zebrafish larvae were injected with (A-B, D, F) NR4A2 (0.5 pM, 1 pM, or 2 pM), (A, C, E, G) NR4A3 (0.125 pM, 0.25 pM, or 0.5 pM), (A-G) or control MO (2 pM) at the 1-cell stage. (A) Neutrophils were visualized as GFP-positive events by fluorescent microscopy. (B-C) Total neutrophil numbers were assessed at 80 hpf (n = 20, performed as 3 separate experiments). Larvae were injured at 72 hpf, and neutrophil counts were performed at (D-E) 6 and (F-G) 24 hours postinjury (n = 16, performed as 2 separate experiments). Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest. Significant differences compared with control MO were denoted by ***P < .001 and ****P < .0001.

Discussion

We show that in human neutrophils, PKA activation leads to a profound upregulation of NR4A2 and NR4A3 mRNA, which is paralleled by a delay in neutrophil apoptosis. PGE2 treatment also delays neutrophil apoptosis and upregulates NR4A2/3 in a PKA-dependent manner. Moreover, NR4A3 expression is increased at sites of neutrophilic inflammation in human intradermal models, and knockdown of NR4A2/3 in murine myeloid cells and zebrafish larvae significantly reduces neutrophil number. These findings demonstrate a role for NR4A family members in neutrophil survival and development and reveal the potential for new therapeutic targets for conditions in which these defects are a key component.

PKA performs important signaling functions in the neutrophil, with roles in migration, adhesion, superoxide production, and matrix metalloproteinase secretion.7,8,20 The roles of PKA in neutrophil lifespan have also been described, and PKA activation has been shown to have both prosurvival and proapoptotic outcomes.21-23 In contrast to the prosurvival roles of PKA in vitro, PKA was found to play a role in the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation in vivo by driving neutrophil apoptosis.23 In our study, activation of PKA by N6/8-AHA, a selective PKA type 1 agonist, results in a profound transcriptional response and upregulated more genes in neutrophils than any other proinflammatory stimulus tested. In addition, compared with the remaining stimuli, PKA activation induced the expression of a unique apoptosis transcriptome, including the induction of JNK, IL-4, MMP9, PKC, and NR4A2/3. Within this unique PKA transcriptome was the downregulation of a number of important proapoptotic genes, including DEDD, a caspase signaling molecule, TRADD, the multideath receptor adaptor protein, and the tumor suppressor RUNX3. Selected qPCR validation assays showed that the targets most highly regulated by N6/8-AHA were NR4A2 and NR4A3, linking them to PKA activation in our studies. The induction of NR4A3 by conditioned supernatant may reflect the presence of PKA signaling agonists, such as adenosine or prostaglandins.

The NR4A family of orphan nuclear receptors is emerging as an important regulator of cellular function, with clear roles in inflammatory signaling.24 Although the upstream agonists of NR4A receptors in neutrophils are not known, they are activated by a number of signaling pathways in other cell types, including PKA and PGE2.25,26 Little is known about NR4A2/3 gene expression in the human neutrophil, and expression of NR4A/3 at the protein level has yet to be demonstrated for this cell type due to the lack of reliable antibodies. Two array studies have shown induction of NR4A family members, in particular NR4A3 in LPS and GM-CSF–/IFN-γ–treated human neutrophils, although in our study, LPS did not regulate NR4A2/3 in vitro.16,27 This may be due to differences in cell purities because small numbers of contaminating monocytes or eosinophils may yield high gene copy numbers.28 A recent murine study has shown the induction of NR4A genes in inflammatory neutrophils isolated from mice that developed serum-transfer arthritis, providing evidence for NR4A regulation at sites of inflammation in vivo.29 Consistent with these findings, we show an increase in NR4A3 mRNA expression at sites of neutrophilic inflammation in human intradermal endotoxin challenge models (supplemental Figure 4), although it is not possible to be certain of the cellular origin of the transcripts. the data suggest that NR4A3 may be a suitable target to which antiinflammatory therapeutic strategies may be designed, although this would require further study. A study by Pei et al30 shows NR4A1 protein expression in macrophages and other cells, including smooth muscle cells, within human coronary artery atherosclerotic plaques, further demonstrating a clinical relevance for NR4A family expression at sites of inflammation.

Our data link NR4A2/3 expression to neutrophil survival, in that NR4A2/3 transcripts are degraded at time points that precede spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, and agonists that induce NR4A expression also delay neutrophil cell death. In all cases, the upregulation of NR4A2/3 transcripts was PKA dependent, linking NR4A regulation exclusively to upstream PKA signaling. These experiments are limited in that an NR4A inhibitor would provide definitive evidence that NR4A was essential in modulating PKA-dependent human neutrophil survival, however no such pharmacological tools existed at the time of study. To address this further, NR4A gene knockdown approaches were explored. Although neutrophils are genetically intractable, siRNA strategies were possible in hoxb8 conditionally immortalized murine myeloid progenitor cells, in which NR4A2, but not NR4A3 gene knockdown reduced cell proliferation. It is not clear whether NR4A2 knockdown murine neutrophils fail to differentiate or die prematurely by apoptosis, although the proportion of mature neutrophils was the same in all siRNA-transfected populations, and the increase in Annexin V–positive cells in combination with the prosurvival effect of N6/8-AHA may suggest that the latter is more likely. NR4A2/3 knockdown in a neutrophil reporter zebrafish line results in a significant reduction in total neutrophil numbers, suggesting that the NR4A family may play a role in neutrophil differentiation in vivo. These findings are supported by the results obtained from studies of mCMPs that, taken together, begin to reveal a role for NR4A2/3 in myeloid cell development and differentiation. In support of this, a role for the NR4A family in regulating T cell and monocyte homeostasis has been described by others.31,32 Interestingly, augmented NR4A2/3 expression has been demonstrated in bone marrow mononuclear cells and myeloid progenitors from patients with aplastic anemia and acute myeloid leukemia, further supporting roles for the NR4A family in the context of normal bone marrow development.33,34 A role for NR4A2 and not NR4A3 in mCMP may reflect divergent roles for NR4A members in mice, or perhaps that NR4A3 can compensate for the absence of NR4A2. Consistent with this, distinct roles are seen in other models where NR4A3 has been shown to control the proliferation of human hepatocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells,35,36 and NR4A2 overexpression in human synoviocytes promotes proliferation and survival.37

Although we show that NR4A2/3 may play a role in neutrophil proliferation and homeostasis, we were unable to demonstrate a role for NR4A2/3 in the resolution of inflammation in zebrafish tail injury models in vivo. This may reflect that, aside from the induction of apoptosis, reverse migration away from injury may also play a significant part in inflammation resolution in this organism.38 In support of this, PKA is thought to be a negative regulator of neutrophil migration in vivo, which may in part explain why the loss of PKA signaling does not impede migration of neutrophils away from the site of inflammation.5,39 A conditional neutrophil NR4A knockout strategy would reveal more about the specific role of NR4A in the neutrophil, but is beyond the scope of this study.

In conclusion, in this study, we show an important role for the NR4A receptors in regulating neutrophil lifespan and homeostasis. Understanding the signaling underpinning these functions may help define therapeutic targets for diseases driven by defects in neutrophil number and survival.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE94923).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paul Heath (University of Sheffield), Nil Turan (University of Birmingham), and Kim Clarke and Eva Caamano-Gutierrez (both of the University of Liverpool) for assistance with running of the array and data processing. The authors also thank the volunteers and patients who contributed to this study.

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council grant (G0801983), a National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Fellowship (BRF-2011-003), and a Heart Research UK Research Training Fellowship (RTF06/11).

Authorship

Contribution: S.D.P., J.C., E.C.P., N.V.O., K.H., A.B., and A.R. carried out the practical experiments; P.T. provided mCMPs and intellectual input; I.S. and F.F. carried out the bioinformatics and array analysis; S.A.R., L.R.P., M.K.B.W., and I.S. conceived the study, designed experiments, and reviewed data; L.R.P. wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to revising and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lynne R. Prince, Department of Infection, Immunity and Cardiovascular Disease, University of Sheffield, Beech Hill Rd, Sheffield S10 2RX, United Kingdom; e-mail: l.r.prince@sheffield.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

L.R.P. and S.D.P. are joint first authors.

M.K.B.W. and I.S. are joint senior authors.

![Figure 1. Regulated gene clusters in stimulated neutrophils. Neutrophils were cultured for 4 hours with N6/8-AHA (1 mM) (PKA), monocyte-conditioned supernatant (SN), GM-CSF (100 U/mL], LPS (1 μg/mL), and under hypoxic conditions, after which, the RNA was analyzed by Affymetrix microarray (GeneChip HU133 Plus 2.0 array). Using the DAVID Web-based functional analysis application we identified several functional terms that were overrepresented in the list of differentially expressed genes. This figure represents the differential expression status of genes in the Gene Ontology term GO:004281 (regulation of apoptosis), which was regulated by each stimulus. Greater than twofold upregulation is indicated in red, no change is indicated in gray, and greater than twofold downregulation is indicated in green. Shown are all genes (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated by N6/8-AHA. Please refer to supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site) for DAVID analysis files and supplemental Figure 1 for a complete figure of all regulated genes within GO:004281.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/8/10.1182_blood-2017-03-770164/4/m_blood770164f1.jpeg?Expires=1769446879&Signature=MFUoyOZPbgc21iDNyWkA9cKixhuby52NDlcT39EXoKf25fEHCaTswARQoZtm66IKomcMMvdQqGWnZu~N1b1VwiO9y-dy-9ExRExzKadxU3F54lpgR0GZG26mgQchsaDK-cxyjbRvcnCKMX7JuLvMD3B3g5jkysrWK3YhTZw1R~vhl6a8r-eDimbOYg7FcgffEI7FGHUFl-IX9ZaUuKIc8~t8VcWg9eqaAR5zs5U2Wlj0QmGVAHraaAGgHBhRZ9bC53XYY0nAnrnKUE~JW9O3FvDnrTnUx4nIRbDunKH64m4MqHd2KFiQ3nHL~OI7yqFsF0geJPorFzfRIyeVAvSgCA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Regulated gene clusters in stimulated neutrophils. Neutrophils were cultured for 4 hours with N6/8-AHA (1 mM) (PKA), monocyte-conditioned supernatant (SN), GM-CSF (100 U/mL], LPS (1 μg/mL), and under hypoxic conditions, after which, the RNA was analyzed by Affymetrix microarray (GeneChip HU133 Plus 2.0 array). Using the DAVID Web-based functional analysis application we identified several functional terms that were overrepresented in the list of differentially expressed genes. This figure represents the differential expression status of genes in the Gene Ontology term GO:004281 (regulation of apoptosis), which was regulated by each stimulus. Greater than twofold upregulation is indicated in red, no change is indicated in gray, and greater than twofold downregulation is indicated in green. Shown are all genes (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated by N6/8-AHA. Please refer to supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site) for DAVID analysis files and supplemental Figure 1 for a complete figure of all regulated genes within GO:004281.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/8/10.1182_blood-2017-03-770164/4/m_blood770164f1.jpeg?Expires=1769454217&Signature=mbFBavgCI5QOPkBnZdy1RRYadv496S8m1O8n13QhPu9ZsvwoOStYmhhI9pXHyKyu4PcjM1jIARXWnhBn---D2q18G4l4ZQlqcCkI0t4Wh~5T-RvRxOmR3PHHze81VxW3inLLQw4L6PT6vSVy4Zf02OTyRk5HgHeIW3mjUT~dA35Uz~WKeFqREO1rlg~BBUll9WuCIEy6DUDoNl2oGa04m0AYwVGDjqkEMZVLsp6wLX4parIsmYszYSZ4rQDLRWZCTtm4h-ja668xpoS6zAbjJCaXouukpC-Px76WcRRwdO0szPCN4bA30gPpf8~mLkEReZJP6po9Em3mblampMwsBg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)