TO THE EDITOR:

Most cases of genetic iron overload are characterized by elevated systemic iron levels and iron deposition in parenchymal cells due to inadequate expression of hepcidin. Here, we present a novel mouse model of iron overload due to selective overexpression of Smad7 in hepatocytes. Transgenic mice present low hepcidin levels and iron accumulation prevalently in the liver, implying that hepatic Smad7 overexpression causes severe liver iron overload in mice. We speculate that patients with high Smad7 expression in the hepatocytes may therefore be at risk of developing liver iron overload.

Regulation of systemic iron homeostasis critically depends on the adequate expression of the small liver peptide hormone hepcidin.1 Large bodies of evidence demonstrate that impaired transforming growth factor-β (Tgf-β)/bone morphogenic protein (Bmp)/Smad signaling underlies low hepatic hepcidin expression. More precisely, mice with genetic disruption of endothelial Bmp2 or Bmp6,2,3 hepatic Bmp receptors type I (Alk3, Alk2),4 Bmp coreceptor hemojuvelin (Hjv),5 or hepatic Smad46 show impaired Smad signaling and low hepcidin expression; in turn, low hepcidin fails to inhibit iron uptake, which results in enhanced iron deposition in various tissues.

In the canonical signaling pathway, Tgf-β family members, which include Tgf-β, Bmps, and activins, as well as nodal, growth, and differentiation factors, transduce signals by binding to type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors to induce phosphorylation of the receptor (R)-activated cytoplasmic Smad-signaling molecules; subsequently R-Smads complex with Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus where, in cooperation with other nuclear factors, they regulate the transcription of target genes.7,8 Inhibitory (I) Smads, Smad6 and Smad7, are induced by Smad signaling and act in negative feedback control mechanisms.7 Whereas Smad7 acts as pan inhibitor of both Tgf-β– and Bmp-induced Smad signaling, Smad6 preferentially inhibits the latter.7 Smad7 antagonizes Tgf-β signaling in the cytoplasm by blocking R-Smad phosphorylation and by modulating Tgf-β receptor activity either by dephosphorylation or degradation, or by reducing its transcription.9 In the nucleus, Smad7 inhibits Tgf-β signaling by disrupting the formation of functional R-Smad/Smad4 complexes and their binding to DNA.10

I-Smads, and in particularly Smad7, are important signal transducers and key regulators of cellular processes including proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and immune responses.9,11 A number of studies pinpointed to a complex role of Smad7 in several cancers where it either inhibits or promotes cancer development depending on cancer type and context.12 Importantly, I-Smads recently emerged as novel regulators of hepcidin. We found that adenoviral overexpression of Smad7 or Smad6 decreased hepcidin levels in primary hepatocytes, whereas RNA interference–mediated inhibition of Smad7 or Smad6 increased hepcidin expression.13,14 These in vitro data proposed that I-Smads, by modulating hepcidin expression, might play an important role in the regulation of systemic iron homeostasis. Hence, we generated mice with targeted overexpression of Smad7 in hepatocytes (Alb-Smad7-tg mice) (Figure 1A-B) (supplemental Material and methods, available on the Blood Web site).

Generation of hepatocyte-specific Smad7-overexpressing mice and liver status. (A) Schematic presentation of the Smad7-expression cassette: downstream of the albumin regulatory elements (Alb.Enh.-Promotor) are globin intron sequences (Intron) and a lac-Z reporter gene (β-Gal) with polyA signal (pA), flanked by 2 loxP sites (indicated by blue triangles). Downstream of the second loxP site is the murine Smad7 complementary DNA with another polyA signal. The construct is flanked by insulator sequences (Ins.) to minimize the influence of neighboring genomic regulatory sequences. (B) LacZ staining of the livers of wild-type (wt) mice and Smad7-tg single-transgenic animals showing a clear and strong signal; liver sections from 2 Alb-Smad7–transgenic animals are shown to demonstrate partial to no staining reactions (original magnification ×40). (C-D) Presence of hepatic fibrosis was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for α-smooth-muscle actin (α-SMA) expression, extracellular matrix–producing cells (scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm), and Sirius red (scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm), respectively. (E) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Smad7 in the liver of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5), measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (F) Immunohistochemistry for Smad7 expression (scale bar, 50 μm) on liver sections from control and Alb-Smad7-tg mice (arrows indicate positive brown-colored staining). (G-H) Immunoblot analysis and relative quantification of pSmad1, total Smad1, and β-actin proteins in the livers of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice (n = 3 per group). (I-J) Immunohistochemistry for Smad2 phosphorylation and quantification of pSmad2+ hepatocyte nuclei per field on liver sections from Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice (I: scale bar, 200 μm; inset scale bar, 100 μm). Images are representative staining of 2 to 3 mice per group. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and results are shown as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). For statistical analysis, a nonparametric distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test were used. *P < .05; **P < .005; ***P < .0005.

Generation of hepatocyte-specific Smad7-overexpressing mice and liver status. (A) Schematic presentation of the Smad7-expression cassette: downstream of the albumin regulatory elements (Alb.Enh.-Promotor) are globin intron sequences (Intron) and a lac-Z reporter gene (β-Gal) with polyA signal (pA), flanked by 2 loxP sites (indicated by blue triangles). Downstream of the second loxP site is the murine Smad7 complementary DNA with another polyA signal. The construct is flanked by insulator sequences (Ins.) to minimize the influence of neighboring genomic regulatory sequences. (B) LacZ staining of the livers of wild-type (wt) mice and Smad7-tg single-transgenic animals showing a clear and strong signal; liver sections from 2 Alb-Smad7–transgenic animals are shown to demonstrate partial to no staining reactions (original magnification ×40). (C-D) Presence of hepatic fibrosis was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for α-smooth-muscle actin (α-SMA) expression, extracellular matrix–producing cells (scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm), and Sirius red (scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm), respectively. (E) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Smad7 in the liver of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5), measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (F) Immunohistochemistry for Smad7 expression (scale bar, 50 μm) on liver sections from control and Alb-Smad7-tg mice (arrows indicate positive brown-colored staining). (G-H) Immunoblot analysis and relative quantification of pSmad1, total Smad1, and β-actin proteins in the livers of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice (n = 3 per group). (I-J) Immunohistochemistry for Smad2 phosphorylation and quantification of pSmad2+ hepatocyte nuclei per field on liver sections from Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice (I: scale bar, 200 μm; inset scale bar, 100 μm). Images are representative staining of 2 to 3 mice per group. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and results are shown as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). For statistical analysis, a nonparametric distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test were used. *P < .05; **P < .005; ***P < .0005.

Transgenic mice developed normally with no overt phenotypic abnormalities. The livers from transgenic mice showed no signs of fibrosis (Figure 1C-D). We demonstrate that ectopically overexpressed Smad7 is predominantly localized in the nucleus of hepatocytes of transgenic mice (Figure 1E-F). Principally, Smad7 resides in the nucleus and Tgf-β stimulation is needed for its partial cytoplasmic distribution.15 We next measured the levels of phosphorylated R-Smads in the livers of control and Smad7-overexpressing mice. We found no significant changes in the levels of pSmad1 between control and transgenic mice by western blot analysis using the whole-cell liver extracts (Figure 1G-H). Similarly, the levels of pSmad2 did not show statistically significant variation, however, there was a tendency toward less pSmad2 positively stained hepatocytes nuclei in transgenic mice (Figure 1I-J), suggesting that Smad7 may to some extent reduce Smad2 phosphorylation. Importantly, increased hepatic Smad7 expression resulted in significant downregulation of hepcidin (Hamp) (Figure 2A), substantiating our previous in vitro findings.13 Similarly, the expression of a number of Tgf-β/Bmp target genes, including Tgf-β1, Id1, Activin, SnoN, and Col4a1, was decreased in the livers of transgenic mice (Figure 2B). These findings suggest that Smad7 might act as transcriptional regulator rather than a mere regulator of Smad signaling. Indeed, accumulating evidence showed that Smad7 acted as transcriptional suppressor where its binding to DNA via the Mad homology 2 (MH2) domain interfered with formation of a functional R-Smads/Smad4–DNA complex.10,16 Moreover, Smad7 can also act as transcriptional corepressor in cooperation with Yin Yang 1 (YY1)17 and histone deacetylase (HDAC1).16 Future investigations may determine whether Smad7 interaction with protein-modification enzymes such as HDAC1 mediates an epigenetic regulation of hepcidin expression.

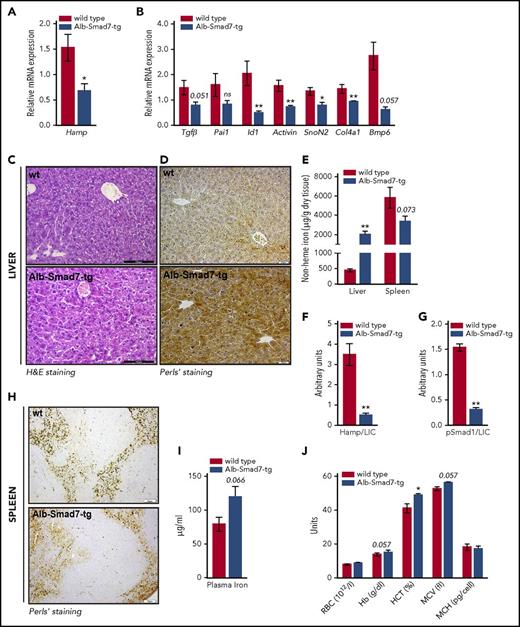

Iron overload phenotype in hepatocyte-specific Smad7-overexpressing mice. (A-B) Relative mRNA expression of hepcidin (Hamp) and several Tgf-β/Bmp target genes in the liver of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5), measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) Hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) staining (scale bar, 100 μm) and (D) Perls’ staining (scale bar, 20 μm) for iron depositions in liver of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (E) Nonheme iron content in liver and spleen of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5). (F-G) Normalization of hepcidin and of phosphorylated Smad1 levels to liver iron in Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (H) Perls’ staining (scale bar, 50 μm) in the spleen of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (I) Plasma iron levels in Alb-Smad7-tg mice (n = 7) compared with control mice (n = 3). (J) Hematological indices in Alb-Smad7-tg mice compared with control mice (n = 3 mice per group). Images are representative staining of 3 mice per group. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and results are shown as mean ± SEM. For the statistical analysis, a nonparametric distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test were used. *P < .05; **P < .005; ***P < .0005. Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; LIC, liver nonheme iron content; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cell.

Iron overload phenotype in hepatocyte-specific Smad7-overexpressing mice. (A-B) Relative mRNA expression of hepcidin (Hamp) and several Tgf-β/Bmp target genes in the liver of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5), measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) Hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) staining (scale bar, 100 μm) and (D) Perls’ staining (scale bar, 20 μm) for iron depositions in liver of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (E) Nonheme iron content in liver and spleen of Alb-Smad7-tg (n = 7) and control mice (n = 5). (F-G) Normalization of hepcidin and of phosphorylated Smad1 levels to liver iron in Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (H) Perls’ staining (scale bar, 50 μm) in the spleen of Alb-Smad7-tg and control mice. (I) Plasma iron levels in Alb-Smad7-tg mice (n = 7) compared with control mice (n = 3). (J) Hematological indices in Alb-Smad7-tg mice compared with control mice (n = 3 mice per group). Images are representative staining of 3 mice per group. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and results are shown as mean ± SEM. For the statistical analysis, a nonparametric distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test were used. *P < .05; **P < .005; ***P < .0005. Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; LIC, liver nonheme iron content; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cell.

Given that transgenic mice show low hepcidin expression, we next analyzed systemic iron levels. We observed significant iron overload in the livers of transgenic mice with abundant iron deposition predominantly in the periportal region without obvious histological alterations (Figure 2C-E). A similar iron deposition pattern is observed in mouse models of primary iron overload (hemochromatosis) due to Hfe-, TfR2-, and hepatocyte-specific Alk2 deficiency.4,18 Hfe, TfR2, and Alk2 regulate hepcidin expression in response to iron/Bmp6 signaling; consequently, the lack of these proteins results in impaired Smad signaling, low hepcidin expression, and profound iron overload.4,18 Thus, in regard to liver iron, hepcidin and pSmad levels are inappropriately low in these mouse models. The same is seen in mice with overexpression of Smad7 in hepatocytes (Figure 2F-G), implying that suppression of hepcidin by Smad7 contributes to a substantial increase in liver iron stores. By contrast, iron levels in the spleen and plasma, as well as hemoglobin values, were not significantly different in transgenic mice compared with controls (Figure 2E,H-J). Taken together, we show that mice with selective overexpression of Smad7 in hepatocytes develop liver iron overload. Whether deficiency of Smad7 in hepatocytes may enhance hepcidin expression and thereby affect iron homeostasis is currently unknown and will be interesting to investigate further.

Our findings bring attention to conditions characterized by acquired iron overload, as is often seen in chronic viral or nonviral hepatitis, which can progress to end-stage liver disease including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections,19 HCV-transgenic mice,20 and murine models of alcoholic liver disease21 frequently exhibit liver iron overload and low hepcidin expression. Importantly, increased hepatic Smad7 expression was recently reported in patients with chronic HCV infections.22 Furthermore, high Smad7 expression was detected in HCC nodules when compared with surrounding nontumorous liver tissue.23 HCC patients and animal models of HCC present low hepcidin expression.24,25 In light of our findings, we propose that hepcidin expression in these conditions may further be suppressed by the action of hepatocyte-specific Smad7. We speculate that patients with increased hepatic Smad7 expression may therefore be at risk of developing liver iron overload. This in turn may accelerate disease progression and contribute to even more adverse outcome. Whether high Smad7 expression may serve as a reliable marker of chronic liver diseases and progression to HCC, and whether therapeutic interventions to decrease Smad7 levels may help to normalize hepcidin expression and prevent liver iron overload and cancer development, warrant further investigations.

Collectively, our results unravel novel biological function of Smad7 required for the control of liver iron metabolism.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank H.-J. Gröne, German Cancer Research Centre, Heidelberg, for assistance with pathological analysis.

This work was supported by the German Liver Foundation (Deutsche Leberstiftung [M.V.S.]) and in part by Ulm University (M.V.S.). M.U.M. acknowledges funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1036). F.T. and S.D. acknowledge funding from the Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) program LiSyM (grant PTJ-FKZ: 031L0043) and the People Program (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework (FP7/2007-2013).

Authorship

Contribution: D.L. performed the experiments; F.T., S.H., and J.W. performed immunohistochemistry staining; T.M. and A.T. provided the mice; M.U.M. and S.D. contributed to the experimental setup planning and edited the manuscript; M.V.S. designed the study, planned the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Maja Vujić Spasić, Institute of Comparative Molecular Endocrinology, Ulm University, 89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: maja.vujic@uni-ulm.de.

REFERENCES

Author notes

M.U.M., S.D., and M.V.S. share senior authorship.