Inability to provide transfusion support to patients with leukemia is a major cause of delays in hospice enrollment for end-of-life (EOL) care. In this issue of Blood, LeBlanc et al explore the relationship between transfusion dependence (TD), time to hospice enrollment, and quality of EOL care in patients with leukemia.1

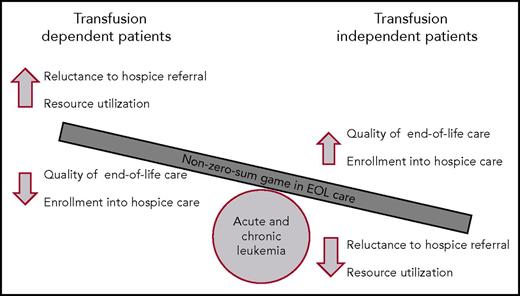

The zero-sum game of transfusion support during EOL care in patients with acute and chronic leukemia. For patients who are not dependent on transfusion, providers are more willing to refer patients to hospice, which increases hospice enrollment with improvements in quality of EOL care and decreases use of resources for patients with leukemia. Conversely, for patients who are dependent on transfusion of blood products, increased provider reluctance leads to decreased enrollment in hospice for EOL care, worse quality of care, and an increase in use of resources during the EOL care.

The zero-sum game of transfusion support during EOL care in patients with acute and chronic leukemia. For patients who are not dependent on transfusion, providers are more willing to refer patients to hospice, which increases hospice enrollment with improvements in quality of EOL care and decreases use of resources for patients with leukemia. Conversely, for patients who are dependent on transfusion of blood products, increased provider reluctance leads to decreased enrollment in hospice for EOL care, worse quality of care, and an increase in use of resources during the EOL care.

Acute leukemias (acute myeloid leukemia [AML] and acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL]) are devastating and often fatal malignancies characterized by an acquired and progressive bone marrow failure. Without treatment, the median overall survival of patients with AML or ALL ranges between 6 and 8 weeks, independent of patient age.2,3 In addition, most adult patients with acute leukemia will succumb from their disease or complications. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program demonstrate that the 5-year survival for patients with AML remains less than 30%. The 5-year survival for ALL patients older than age 50 years is equally disappointing (<35%).4 For these reasons, EOL care remains an integral component of the care provided to most patients with acute leukemia, independently of the intent of initial treatment. Fortunately, 5-year survival rates for patients with chronic leukemia have improved significantly over the past decade.

Given that bone marrow failure in patients with leukemia often presents with clinically significant cytopenias, TD is common in patients with acute and chronic leukemia. In these patients, up to 40% may be dependent on transfusions of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), platelets, or both at the time of diagnosis.5 In addition, prior studies have demonstrated that the presence of TD at diagnosis and the intensity of TD during treatment are prognostic in patients with leukemia.5,6 Although the observed rate of TD in patients with acute leukemia enrolled in hospice remains mostly underrecognized, limited data suggest that progressive cytopenias are common in these patients, with up to one-third of them being dependent on PRBC transfusion and nearly half being dependent on platelet transfusion.7

The report by LeBlanc et al on the correlation between blood TD, the use of hospice services after exhaustion of treatment options, and the quality of EOL care in patients with leukemia is the first to assess the impact of TD on the use of hospice services in patients with acute and chronic leukemia. The current cancer registry cohort, extracted from the SEER-Medicare data set, establishes the real-world incidence of TD for patients with acute and chronic leukemia who are enrolled into hospice and the independent impact of TD on median duration of EOL hospice care (6 days for transfusion-dependent patients vs 11 days for transfusion-independent patients; P < .001). Although the proportion of transfusion-dependent patients enrolled into hospice for their EOL care was lower than that for transfusion-independent patients, the study also demonstrated that greater transfusion support needs were associated with lower rates of enrollment into hospice. This is important information, because enrollment into hospice care, independent of dependency on transfusion of blood products, was associated with improvements in EOL quality measures, such as lower rates of admissions to the intensive care unit, inpatient death, or treatment with chemotherapy within 30 days of death. In addition, these data contrast significantly with those for patients with different solid tumors, in whom the optimal duration of hospice care associated with improved quality of dying and death exceeds 20 days.8

According to a recent survey by health care providers, the inability of most hospices to provide blood transfusions is a major contributor to the underuse of hospice care for patients with acute and chronic leukemia. The survey also showed that most practitioners strongly agree that they would refer more patients to hospice if red cell and/or platelet transfusions were allowed.9 In addition, approximately half of responding practitioners answered that limiting PRBC and/or platelet transfusions within the last days of life was not an acceptable quality metric for patients with hematologic malignancies.9 This creates a clinical dilemma for EOL care in patients with leukemia, especially those with AML and ALL, whereas other supportive measures and transition to hospice play an integral role in the management of these patients. As shown by LeBlanc et al, for these patients, hospice enrollment is clearly associated with several positive EOL quality end points, such as lower rate of inpatient deaths, decreased hospitalization time, and use of resources. LeBlanc et al and others have also shown that enrollment into hospice improves quality of EOL care and, in certain situations, overall survival (not addressed by LeBlanc et al). Unfortunately, the limited availability of transfusion support for patients enrolled in hospice limits the benefits of hospice to leukemia patients and is a major roadblock for health care providers who may otherwise refer these patients to hospice care. In game theory, non-zero-sum games are those where 1 player’s gain does not necessarily translate into bad news for the other players. Indeed, in highly non-zero-sum games, the players’ interests overlap entirely. On the basis of the results from LeBlanc et al and others, it is time for hospice agencies to reconsider their transfusion support guidelines so that patients with hematologic malignancies can readily benefit from hospice enrollment earlier in the course of their EOL care (see figure). These guidelines would be akin to services allowed by hospice programs for pediatric oncology patients for whom transfusion support is permitted by ∼70% of agencies. More flexible hospice services lead to increased referral to hospice and more patients dying at home.10

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.