In this issue of Blood, Ghia et al observe that a proportion of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) harbor mutations in genes involved in the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway resulting in expression of glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1). They also find that GLI1 is expressed in CLL cells without evidence of Hh mutations and that the high GLI1 levels correlate with disease progression.1

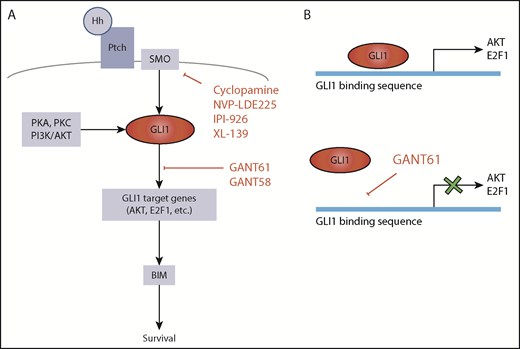

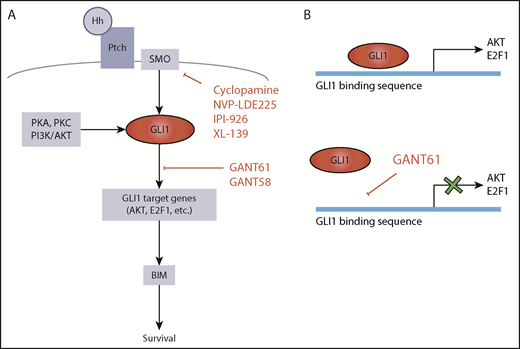

Hedgehog pathway targets for potential therapeutic attack. (A) GLI1 activation is central in the Hh pathway. In the absence of mutations, canonical GLI1 activation occurs following binding of Hh protein to Ptch receptor and consequent activation of SMO. GLI1 can also be induced by PKA, PKC, or PI3K/AKT (SMO-independent GLI1 activation). Hh signaling can be inhibited by constructs that target SMO or by inhibitors of GLI1-induced transcription. (B) GANT61 is a GLI1 antagonist that inhibits GLI1-induced transcription by binding to the GLI1 consensus sequence in the promoters of the target genes.

Hedgehog pathway targets for potential therapeutic attack. (A) GLI1 activation is central in the Hh pathway. In the absence of mutations, canonical GLI1 activation occurs following binding of Hh protein to Ptch receptor and consequent activation of SMO. GLI1 can also be induced by PKA, PKC, or PI3K/AKT (SMO-independent GLI1 activation). Hh signaling can be inhibited by constructs that target SMO or by inhibitors of GLI1-induced transcription. (B) GANT61 is a GLI1 antagonist that inhibits GLI1-induced transcription by binding to the GLI1 consensus sequence in the promoters of the target genes.

A remarkable feature of CLL is the extremely variable clinical behavior, which is known to be influenced by environmental interactions and by genetic changes. There are 2 types of genetic changes affecting CLL. One type is somatic hypermutations of the B-cell receptor (BCR) immunoglobulin gene variable (IGV) region. These mutations are naturally acquired in the B cell of origin and are preserved in the entire CLL clone after transformation. CLL patients with unmutated tumor IGV (U-CLL), of pregerminal center (GC) origin, have a more rapid disease progression than CLL patients with mutated tumor IGV (M-CLL), of post-GC origin.2-4 Variability of outcome likely reflects a variable grade of antigen-driven BCR anergy, which is particularly prominent in M-CLL cells.5 The second type is tumor lesions of genes involved in relevant signaling/metabolic pathways.6 These pathways include those associated with BCR signaling, NOTCH1 signaling, inflammation, WNT signaling, chromatin modification, response to DNA damage, cell cycle control, and RNA processing.6

By focusing their attention on genes not involved in any of these known pathways, Ghia et al have identified a new set of recurrently mutated genes associated with the Hh signaling pathway. This pathway is very important for development, proliferation, and differentiation of mammalian cells. It is activated by the binding of Sonic Hh (SHh), Desert Hh (DHh), or Indian Hh (IHh) ligands to Patched1 or Patched2 (PTCH1-2) receptors, eventually resulting in the activation of GLI1 transcription factor by Smoothened (SMO) (see figure). However, other ligand-independent mechanisms can lead to GLI1 activation. Gene mutations resulting in activation of GLI1 have been described in a variety of cancers in which the Hh pathway is important,7 whereas information on the Hh pathway in CLL has remained circumstantial.8,9 In their article, Ghia et al document mutations of Hh pathway-associated genes in 11% of CLL cells. The acquisition of mutations in any of these genes, including the epigenetic regulators EZH2 and CREBBP, associates with expression of GLI1 and predicts for relatively short time to first treatment, implying that activation of Hh signaling has a critical role for disease progression in CLL.

The importance of Hh pathway activation in CLL is further highlighted by some additional observations. One is that almost 40% of CLL cells that do not harbor Hh pathway gene mutations also express GLI1 and that GLI1 expression then seems to inform disease progression independently of Hh mutations. This is particularly evident in M-CLL, whereas other genetic lesions associated with more rapid outcome are less frequent.5 Another observation is that viability of GLI1+ CLL cells, but not GLI1– CLL cells, is significantly reduced by GLI1-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or by the GANT61 small molecule inhibitor of GLI1. Inhibition by either siRNA or GANT61 leads to reduced expression of GLI1 gene targets E2F1 and AKT1 and ultimately of BIM.10

Other Hh pathway inhibitors, including SMO inhibitors, have been proposed for therapeutically attacking cancer cells. However, SMO inhibitors would be able to block ligand-dependent Hh pathway activation, but they would still be ineffective in CLL cells that harbor GLI1 proactivating mutations of SMO or downstream molecules.9 The attraction of inhibitors such as GANT61 is that they may successfully operate in all the GLI1+ CLL cells by blocking either ligand-dependent or ligand-independent (by proactivating gene mutations) Hh pathways. The data from the Ghia et al study suggest that an approach with molecules targeting GLI1 may not be particularly toxic, because it does not seem to affect GLI1– cells.

These new results indicate that Hh seems to be another critical pathway that needs further investigation in CLL to help us better understand pathogenesis of a large subset of CLL cells (∼40%). This may be one of the subsets in which we will need to assess new molecules for therapeutic attack, when the currently available precision therapies, such as BCR-associated inhibitors or BH3 mimetics will fail to overcome the adaptability of CLL tumor cells for survival.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.