Abstract

Recent genome-wide studies have revealed a plethora of germline variants that significantly influence the susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), thus providing compelling evidence for genetic inheritance of this blood cancer. In particular, hematopoietic transcription factors (eg, ETV6, PAX5, IKZF1) are most frequently implicated in familial ALL, and germline variants in these genes confer strong predisposition (albeit with incomplete penetrance). Studies of germline risk factors for ALL provide unique insights into the molecular etiology of this leukemia.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is an archetype of a blood cancer that is highly responsive to pharmacotherapy. With successive trials over the past 50 years, refinement of risk-adapted combination chemotherapy has led to dramatic improvements in the survival rates of this hematological malignancy,1 with stem cell transplantation reserved for certain high-risk populations as the only curative therapy.2,3 Although the etiology of ALL in children and adults remains incompletely characterized, there has been significant progress in recent years in our understanding of the genetic risk factors associated with ALL.

Inherited basis of ALL risk

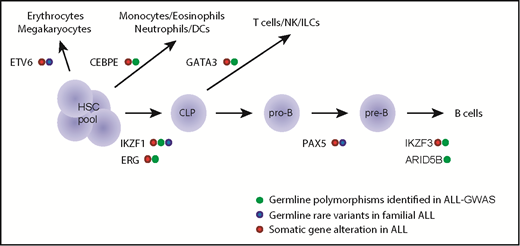

The contribution of inherited genetics to ALL leukemogenesis can be divided into 2 categories: low-penetrance susceptibility conferred by common germline polymorphisms (eg, a 1.5-fold to twofold increase in relative leukemia risk) and high-penetrance predisposition conferred by rare germline variants (eg, >10-fold increase in relative risk).4-6 For example, large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified at least 12 genomic loci with common polymorphisms associated with ALL susceptibility, the majority of which are in genes encoding hematopoietic transcription factors (eg, ARID5B,7-10 IKZF1,7-10 GATA3,11,12 CEBPE,8 ERG,13 and IKZF314 ) (Figure 1). Although these risk alleles individually produce a modest effect and may be of limited clinical significance, in aggregate they can give rise to as much as a ninefold increase in leukemia risk for subjects with risk alleles in multiple genes compared with subjects with no risk alleles.10 More importantly, the discovery of novel ALL risk genes through GWASs also points to new pathways underlying leukemia pathogenesis.7,8,10

Genetic variations in hematopoietic transcription factors contribute to the inherited risk of developing ALL. This diagram shows transcriptional factor genes in which germline genetic variation have been associated with ALL risk (eg, common polymorphisms linked to ALL susceptibility and rare variants linked to familial predisposition to ALL). The transcriptional factors are drawn largely according to the hematopoietic developmental stage at which they are known to operate. CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; DCs, dendritic cells; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; ILCs, innate lymphoid cells; NK, natural killer cells; pre-B, pre-B cell; pro-B, pro-B cell.

Genetic variations in hematopoietic transcription factors contribute to the inherited risk of developing ALL. This diagram shows transcriptional factor genes in which germline genetic variation have been associated with ALL risk (eg, common polymorphisms linked to ALL susceptibility and rare variants linked to familial predisposition to ALL). The transcriptional factors are drawn largely according to the hematopoietic developmental stage at which they are known to operate. CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; DCs, dendritic cells; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; ILCs, innate lymphoid cells; NK, natural killer cells; pre-B, pre-B cell; pro-B, pro-B cell.

The second form of genetic inheritance of ALL is mediated by rare germline variations associated with strong leukemia predisposition, often with familial clustering. In fact, the occurrence of ALL has long been documented in a variety of genetic syndromes, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), ataxia telangiectasia, and neurofibromatosis type 1. However, cancer predisposition in these cases is not restricted to ALL, which usually represents only a minority of the malignancies present in these families.4,6 The arrival of whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing techniques dramatically improved the resolution and scale at which genetic variations can be discerned, allowing for the discovery of cancer genes in even small nuclear families.15-17 Thanks to these powerful genomic tools, a growing number of genes have been implicated in familial ALL predisposition with varying levels of evidence, including (but not limited to) IKZF1,18-21 PAX5,22,23 ETV6,24-29 SH2B3,30 TP53,31,32 RUNX1,33-35 and TYK2.36 Although relatively rare (eg, explaining <1% of childhood ALL19,24 ), studies of cases with these pathogenic germline variants can offer unique insights into ALL pathogenesis. In this Blood Spotlight, we have elected to highlight ETV6, IKZF1, and PAX5 because of exciting data that emerged recently pointing to them as predisposition genes primarily linked to ALL and their potential roles in benign and malignant blood disorders. We also discuss research opportunities and challenges that arise with these new discoveries.

ETV6, IKZF1, and PAX5 as ALL risk genes

Although somatic ETV6 gene rearrangement (eg, ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene) is one of the most frequent genomic abnormalities in childhood ALL,37,38 germline variants at this locus have not been implicated in this leukemia until recently. Initial reports of germline variants of ETV6 described them as a genetic cause of hereditary thrombocytopenia, but, interestingly, also noted a relatively high frequency of hematological malignancies in carriers (especially B-cell ALL [B-ALL]).25,26 Other loss-of-function germline variants in ETV6 were independently identified in additional pedigrees of familial ALL, confirming it as a leukemia-predisposition gene.24,27-29 Comprehensive ETV6 sequencing in large childhood ALL cohorts identified 31 potentially pathogenic variants in 35 of 4405 patients (0.8%).24 Across different reports, there is a striking clustering of ETV6 variants (linked to platelet disorders and/or ALL) in exons encoding the DNA binding domain, which presumably leads to a decrease in transcription repressor activity.39 In contrast, only a single variant has been reported in the linker domain (although in multiple kindreds), and it may indirectly impair ETV6-DNA interaction.25,26,28,29,40 Based on the data published thus far, it appears that ETV6 variants almost always cosegregate with thrombocytopenia in these families, but with only partial penetrance of B-ALL and rarely with myeloid malignancies.25,27,28 Although the absolute risk of ALL conferred by different ETV6 variants is hard to define without large pedigrees, we estimate a relative risk approaching 23 by comparing the burden of potentially pathogenic variants in the ALL cohort vs in the general population (eg, estimated from ∼130 000 whole-exome or whole-genome sequences in gnomAD).24 This is notable because similar analysis of TP53 variants indicates that LFS may confer only an approximate fivefold increase in ALL risk.32 The cosegregation of thrombocytopenia and ALL in families with germline ETV6 variants points to the importance of this gene in platelet and B-cell development, as well as raises the question of whether its functions in these 2 distinctive lineages of hematopoiesis are independent. Similarly, germline genetic defects in RUNX1 can also have pleotropic effects, giving rise to familial platelet disorder and leukemia (primarily acute myeloid leukemia with rare occurrence of T-cell ALL).33-35 Although ETV6 and RUNX1 have overlapping effects on thrombocytopenia, the differences in the spectrum of leukemia arising from germline variants in these 2 genes clearly indicate strong lineage bias in their potential to promote leukemogenesis.

Challenges and opportunities

Compared with ETV6, IKZF1 plays a more specific role in lymphoid development as a master transcription regulator. Somatic genomic aberrations in IKZF1 are well documented in B-ALL, especially Ph+41,42 and Ph-like ALL,43,44 resulting in loss of transcription factor activity with evidence of dominant-negative effects.45,46 Recently, rare germline IKZF1 variants in the N-terminal DNA binding domains have been linked to inherited immunodeficiency (eg, low B-cell numbers).20 A surprising report subsequently described highly conserved de novo germline IKZF1 missense mutations in patients with early-onset combined immunodeficiency syndrome.21 These subjects present with abnormalities in multiple hematopoietic lineages, including T, B, myeloid, and dendritic cells.21 Strikingly, ALL was observed in both studies in a small subset of carriers with loss-of-function IKZF1 variants, although the investigators did not establish a clear familial transmission with small sample sizes.20,21 In contrast, we recently described a unique kindred of 6 subjects carrying a germline truncating variant in IKZF1 (p.D186fs), 2 of whom developed B-ALL.19 Comprehensive targeted sequencing in 4963 children with newly diagnosed B-ALL identified 27 unique IKZF1 coding variants in 43 patients (0.9%).19 Unlike IKZF1 variants in immunodeficient patients18,20,21 (or somatic IKZF1 mutations in ALL46 ), the ALL-related germline variants are not restricted to the N-terminal regions or zinc finger domains. In fact, only a minority of these variants results in defects in transcription factor activity, whereas many showed a variety of functional effects involving IKZF1 dimerization, localization, cell adhesion, and/or drug sensitivity.19 This diversity in IKZF1 variant functions stands in contrast to that of ETV6, in which pathogenic variants primarily influence DNA binding and its core transcription factor activity.25-28 Given the small number of IKZF1-mediated hereditary ALL cases reported thus far, it is plausible that IKZF1 variants have a lower penetrance of this leukemia than those in ETV6, and pathogenicity of IKZF1 variants in the context of ALL may be challenging to define without comprehensive family histories and in-depth functional characterization.

PAX5 is an another essential transcription factor during B lymphopoiesis, and the PAX5 gene is commonly targeted by a variety of somatic genomic abnormalities in B-ALL (eg, focal deletion, gene fusions, and point mutations).47,48 A recurrent PAX5 germline missense variant (p.G183S) has been identified in 3 unrelated kindreds thus far, in whom an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of B-ALL was observed.22,23 Particularly of note, individuals affected by ALL consistently showed a somatic deletion of the wild-type PAX5 allele, whereas carriers who retained the wild-type allele did not develop ALL, suggesting a simple loss-of-function effect of this germline variant.22 Unlike ETV6 and IKZF1, there have not been comprehensive PAX5 sequencing studies in sporadic childhood ALL; thus, the degree to which germline PAX5 variants contribute to ALL susceptibility remains unclear.

With these discoveries, there is a growing excitement and interest in studying the biology of ALL predisposition, and several research themes have begun to emerge. For example, across different ALL risk genes discussed here, germline genetic variants consistently show incomplete penetrance, requiring the acquisition of a myriad of secondary somatic events to trigger overt leukemogenesis. Mutagenesis studies in mice with heterozygous Pax5 deficiency identified somatic changes in Pax5, Ras, and/or Jak1/3 that significantly accelerated leukemogenesis.49 Intriguingly, Borkhardt and Sanchez-Garcia’s groups50 showed that Pax5+/− mice developed B-ALL only when they were exposed to infection and also revealed somatic Jak3 mutations as a common second hit in the leukemic cells. Similarly, they reported that infection can significantly promote leukemogenic effects of ETV6-RUNX1 in mice, with recurrent somatic alterations in lysine demethylase genes (eg, Kdm5c).51 Infections directly trigger RAG1/2 activation as a host immune defense mechanism,52,53 which can promote widespread DNA rearrangements and mutations,54 thus increasing the chances of acquiring secondary genomic aberrations, as documented in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.55 It is tempting to hypothesize that this mechanism is also operational in ALL with germline ETV6 variants. In fact, germline ETV6 risk alleles are mutually exclusive with ETV6-RUNX1 fusion in ALL, suggesting that they may invoke a common leukemogenic pathway.24 These findings strongly point to the interplay between inherited susceptibility and somatic genomic alterations, with environmental exposures (eg, infection-related activation of RAG activity) as a possible facilitator. In these scenarios, germline variants in hematopoietic transcription factor genes may cause impaired lymphoid development and expansion of immature B-precursor cells that are vulnerable to secondary genetic alterations induced by infectious exposures. Alternatively, inherited defects in these hematopoietic transcription factors can lead to epigenomic changes at their target genes (eg, reduced transcription repression with increased chromatin accessibility), increasing the likelihood of acquiring secondary genomic aberrations at these genomic loci and, thus, transforming preleukemic clones into overt ALL.

Although each ALL risk gene only accounts for a small fraction of childhood ALL, collectively, as a group, inherited susceptibility explains the development of this hematological malignancy in an increasingly significant subset of patients. Therefore, the recognition of genetic predisposition can have a profound clinical impact in a number of ways. For example, donor selection for a hematopoietic stem cell transplant involving families with a leukemia-predisposition variant would need to be considered very carefully. If a germline variant is highly penetrant, carriers of this variant should be avoided as stem cell donors; however, for low-penetrance variants, it is debatable whether this should be factored into clinical decision-making, especially when transplant is the only curative treatment. The threshold of high vs low penetrance certainly has not been established in the field and probably should be adjudicated individually for each patient/family. This is even more complex in the context of returning results of genetic testing for leukemia-predisposition variants to patients and families. With rare exceptions, such as LFS,56 the exact increase in absolute ALL risk has not been established, even though many have already been included in various clinical genetic testing panels. Returning results for variants with modest effects on leukemia risk could potentially impose unnecessary emotional burden and stress on patients and family members; however, these carriers and kindreds are invaluable research subjects and are critical for investigations to precisely define the impact of ALL risk variants. Clinicians and scientists have begun addressing these issues, developing guidelines for clinical interventions, and establishing frameworks for research with sound ethical standards.57-59 Although not without challenges, the nascent field of ALL genetic predisposition is well poised to advance quickly, and a better understanding of the genetic basis of ALL risk will provide important insights into the biology of normal and malignant hematopoiesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grants CA176063 and CA21765) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. Y.G. was supported by Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group overseas scholarship and Nippon Medical School (Japan).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.G. and J.J.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jun J. Yang, St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, Memphis, TN 38105; e-mail: jun.yang@stjude.org.