Key Points

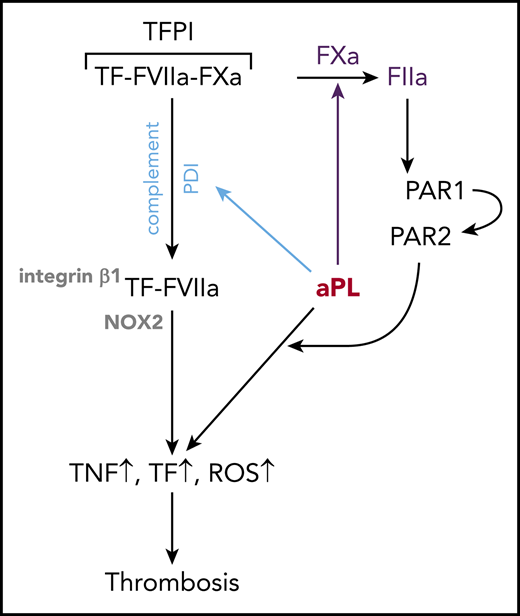

Antiphospholipid antibodies trigger coagulation and inflammatory signaling by dissociating an inhibited TF cell surface complex.

Myeloid cell-expressed TFPI specifically supports aPL-induced thrombosis.

Abstract

Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) with complex lipid and/or protein reactivities cause complement-dependent thrombosis and pregnancy complications. Although cross-reactivities with coagulation regulatory proteins contribute to the risk for developing thrombosis in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, the majority of pathogenic aPLs retain reactivity with membrane lipid components and rapidly induce reactive oxygen species-dependent proinflammatory signaling and tissue factor (TF) procoagulant activation. Here, we show that lipid-reactive aPLs activate a common species-conserved TF signaling pathway. aPLs dissociate an inhibited TF coagulation initiation complex on the cell surface of monocytes, thereby liberating factor Xa for thrombin generation and protease activated receptor 1/2 heterodimer signaling. In addition to proteolytic signaling, aPLs promote complement- and protein disulfide isomerase-dependent TF-integrin β1 trafficking that translocates aPLs and NADPH oxidase to the endosome. Cell surface TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI) synthesized by monocytes is required for TF inhibition, and disabling TFPI prevents aPL signaling, indicating a paradoxical prothrombotic role for TFPI. Myeloid cell-specific TFPI inactivation has no effect on models of arterial or venous thrombus development, but remarkably prevents experimental aPL-induced thrombosis in mice. Thus, the physiological control of TF primes monocytes for rapid aPL pathogenic signaling and thrombosis amplification in an unexpected crosstalk between complement activation and coagulation signaling.

Introduction

The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by persistent autoantibodies, termed antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs), which cause venous or arterial thrombosis and severe pregnancy morbidity.1 Cardiolipin is the prototypic antigen of lipid-reactive aPLs in diagnostic immunoassays, but aPLs display substantial reactivity with other procoagulant phospholipids. The severity of APS is therefore often associated with a prolongation of coagulation times in the lupus anticoagulant assay. In addition, aPLs react with blood proteins, including β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), and by clustering of β2GPI can indirectly activate platelets and endothelial cells through the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8).2,3 However, β2GPI has diverse biological functions as a regulator of complement activity4 and autoimmunity.5 Anticoagulant proteins6,7 are furthermore recognized by certain aPLs, which may cause amplification of coagulation in physiological settings.8 The pathomechanisms of aPL-induced thrombosis are therefore complex.

Clonal analysis of aPLs indicates that lipid reactivity can coexist with protein cross-reactivity,9,10 but sole lipid reactivity is sufficient to cause pregnancy loss11,12 and complement-dependent thrombosis in mice.13,14 In monocytes, endothelial and trophoblast cells lipid-reactive aPLs activate endosomal NADPH-oxidase (NOX), reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and proinflammatory sensitization to toll like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonists.15,,-18 These pathways also induce the coagulation initiator tissue factor (TF), and thereby promote thrombosis.

Monocyte TF plays a pivotal role in APS,19 and stimulation of monocytes with cardiolipin-reactive aPLs in vitro elicits proteome changes also observed in circulating monocytes of patients with APS.20 Lipid-reactive antibodies rapidly convert monocyte TF to a procoagulant form through Fc-mediated complement activation.10,14 These responses are also elicited by lipid-binding monoclonal aPLs cross-reactive with β2GPI, but not by antibodies recognizing β2GPI selectively. Complement activation by aPLs is required for the induction of thrombosis14,21,22 and pregnancy loss.23 Fetal loss also requires TF-dependent signaling through protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2).24 In addition, PAR1 and PAR2 are upregulated on circulating monocytes in patients with APS.25 Thus, there is a complex interplay among complement, coagulation, and proteolytic signaling in the pathogenesis of APS.

In this study, we focused on the early cellular events by which aPLs influence the TF pathway and provide new insights into monocyte activation by aPLs through a synergy of complement and TF-dependent signaling. We uncovered an unexpected role for monocyte-expressed TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI) in aPL-induced thrombosis, delineating a novel priming pathway of monocyte prothrombotic responses in APS.

Methods

Human aPLs

Human monoclonal aPLs representative of patient reactivities, HL5B (cardiolipin-reactive), rJGG9 (β2GPI-reactive), and HL7G (dual reactivity with lipid and β2GPI), were characterized extensively.10,14,26,27 The use of blood samples has been approved by the ethics committee of the state medical association of Rheinland-Pfalz.

Mice

Sex- and age-matched (6-12 weeks) mice were analyzed. TF cytoplasmic domain-deleted (TFΔCT),28,29 PAR1−/−,30 PAR2−/−,31 and TFPIK1flfl (Tfpitm1.1Rdsi)-LysMcre,32 and Lrp8−/− mice33 (Jackson) were backcrossed onto C57BL/6J. Cleavage-insensitive PAR2 R38E,34 thrombin-insensitive PAR1 R41Q,35 and integrin β1flfl LysMcre mice36 were on a C57BL/6N background. All animal procedures were performed with approval of the TSRI IACUC (#08-0009) and the Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz, Germany (23177-07/G14-1043).

Cell culture and isolation

Spleen monocytes were isolated with anti-CD115 beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Human CD14+ cells were isolated from Buffy coats of healthy donors. Monocytes were cultured at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/mL overnight, exposed to inhibitors for 15 minutes, and stimulated with agonist as follows: ARF6 inhibitor Secin H3 (20 µM), αPAR1-ATAP2/WEDE15 (10/25 µg/mL),37 C3 inhibitor compstatin (50 µM), hirudin (100 nM), FXa inhibitor nematode anticoagulant peptide 5 (NAP5; 1 µM),38 endosomal NOX inhibitor niflumic acid (0.1 µM), PAR antagonists (PAR1: RWJ 56110; PAR2: FSLLRY-NH2; 50 µM), PDI inhibitor 16F16 (2 µM), rivaroxaban (1 µM), αTF-10H10 or 5G9 (50 µg/mL), αmouseTF-21E10 (5 µg/mL),39 aPLs HL5B, HL7G, HL5B Fab’2, or control immunoglobulin G (IgG; 500 ng/mL), TLR7 agonist R848 (2 µg/mL).

mRNA expression analysis

Relative quantification of gene expression was performed by real-time PCR on the iCycler iQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) normalized to GAPDH levels. Primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Clotting assays

Procoagulant activity of stimulated monocytes and PS exposure were characterized as described.14 Factor Xa (FXa) procoagulant activity was measured in serum-free supernatant from 5 × 108/mL MM1 cells stimulated for 10 minutes with Fab’2 fragments of HL5B by mixing FX-deficient plasma (Instrumentation Laboratory) 1:1 with purified FXa or supernatant with or without rivaroxaban. Coagulation was initiated with TF (Innovin; Siemens) and recalcification, and clotting times were measured in a KC10 (Amelung, Lemgo, Germany).

Detection of endosomal ROS

Endosomal ROS was detected in cells loaded with the fluorescent probe H2DCFDA (10 µM) in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) after defined stimulation by flow cytometry. ROS-producing cells were more than 80% CD11b+CD115+PI−.

Confocal microscopy

Imaging used a Zeiss LSM 710 NLO confocal laser scanning microscope and a 1.4 Oil Dic M27 63 × plan apochromat objective (Zeiss). Internalization of aPLs was visualized after incubation of cells for 30 minutes with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled HL5B with 50 nM Lysotracker red and nuclear counterstaining (Hoechst 33342). Membranes were stained with 1 µg/mL cholera toxin B (CTB) after stimulation on ice to avoid internalization. TF, FVIIa, FXa, or TFPI trafficking was visualized after incubation of cells with antibodies (αTF-5G9 or 10H10, 50 µg/mL; αFVII-12C7, 3 µg/mL; αFX-f21-4.2C, 5 µg/mL; αTFPI-HG5, 5 µg/mL) and stimulation for 15 minutes with HL5B or IgG and immediate live cell imaging.

Internalization of gp91phox was visualized in cells fixed with phosphate-buffered saline, 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, followed by phosphate-buffered saline, 0.25% saponin, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 2.5% horse serum for 15 to 30 minutes at 20°C. Cells were stained (αgp91phox, 1 µg/mL; αEEA1, 1 µg/mL) in blocking buffer at 25°C for 45 minutes, and counterstained with secondary antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Epitope accessibility of α-FVIIa antibodies was determined by preassembling TF-FVIIa or TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complexes on CHO cells expressing human TF. To measure internalization, surface staining with FITC-labeled antibodies was quenched using 0.4% trypan blue. FXa dissociation was measured by flow cytometry on living cells cultured in 10% human serum by adding αFXa 10 minutes after stimulation. Data were analyzed with FlowJo 7.2 (TreeStar Inc).

Inferior vena cava thrombosis model and arterial ligation models

aPL-amplified thrombus development was evaluated as described.13,14 Briefly, HL5B (1 μg) was injected via jugular catheter into 8- to 12-week-old male mice 1 hour before inferior vena cava flow reduction by ligation over a transiently positioned spacer (0.26 mm). Rhodamine B-labeled platelets and acridine orange labeling leukocytes were infused for thrombus imaging by high-speed fluorescence video microscopy on an Olympus BX51WI. Leukocyte and platelet deposition was similarly monitored in a transient carotid artery ligation model.40 Venous thrombosis induced by flow restriction of the inferior vena cava without aPLs was quantified after 48 hours, as described.41

Statistics

GraphPad Prism 7 was used for group comparisons with parametric Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multicomparison correction (Dunnett).

Results

Prothrombotic aPLs dissociate an inhibited cell surface TF complex

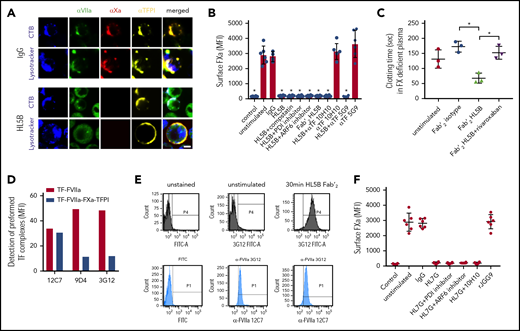

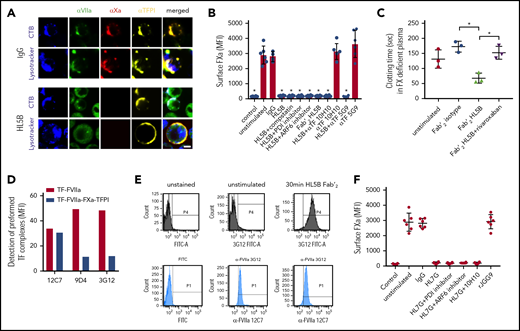

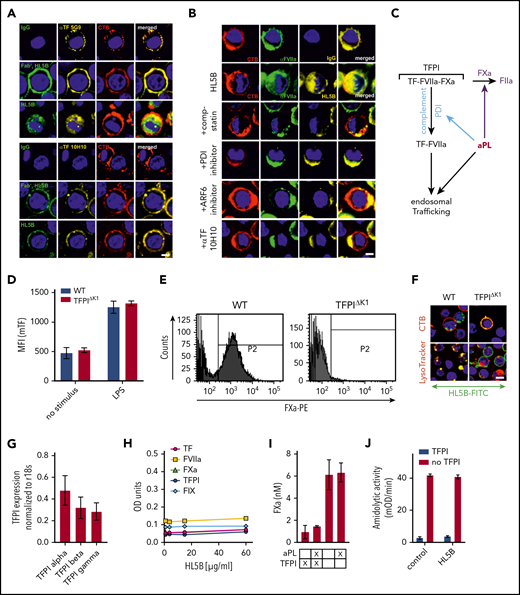

Because lipid-reactive aPLs with or without β2GPI cross-reactivity rapidly activate monocyte TF in thrombosis,14 we hypothesized that TF was cell surface retained in complex with TFPI. We visualized the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex on unstimulated monocytes and found that this complex was disrupted by aPL HL5B (Figure 1A). Stimulation for 15 minutes caused FVIIa internalization into an endo-lysosomal compartment, but TFPI remained cell surface-exposed, and FXa staining disappeared.

Prothrombotic aPLs dissociate an inhibited cell surface TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex. (A) Human monocytic MM1 cells were cultured in human serum, stained with αFVII-12C7 with a known epitope in the FVII protease domain,46 αFX-f21-4.2C, and αTFPI-HG5 (both identified by screening for reactivity with a preassembled TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex on CHO-cells), and imaged on live cells after 15 minutes of exposure to control IgG or aPL HL5B. Nuclei were stained in blue with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI, surface membrane with cholera toxin B (CTB), and endo-lysosomes with Lysotracker or αEEA1 (red). Scale bar = 5 µm. (B) Loss of FXa surface staining on mouse CD115+ splenocytes grown in human serum by flow cytometry after 10 minutes of stimulation; mean ± standard deviation (SD). n = 6. *P < .0062; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test vs unstimulated. (C) FXa clotting activity in the supernatant of aPL-stimulated monocytes; mean ± SD. n = 3. *P < .005; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (D) Detection of TF-FVIIa vs TF-FVIIa-Xa-TFPI on TF-expressing CHO-cells by αVIIa-3G1247 and 9D4 vs 12C7. (E) Coagulation inhibitory αVIIa-3G12 vs αFVII-12C7 reactivity on monocytic cells before and after stimulation with aPL HL5B Fab’2, which does not cause TF-FVIIa internalization. (F) β2GPI- and lipid-reactive HL7G, but not rJGG9, with sole β2GPI reactivity can induce FXa release from mouse CD115+ splenocytes; mean ± SD. n = 6.

Prothrombotic aPLs dissociate an inhibited cell surface TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex. (A) Human monocytic MM1 cells were cultured in human serum, stained with αFVII-12C7 with a known epitope in the FVII protease domain,46 αFX-f21-4.2C, and αTFPI-HG5 (both identified by screening for reactivity with a preassembled TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex on CHO-cells), and imaged on live cells after 15 minutes of exposure to control IgG or aPL HL5B. Nuclei were stained in blue with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI, surface membrane with cholera toxin B (CTB), and endo-lysosomes with Lysotracker or αEEA1 (red). Scale bar = 5 µm. (B) Loss of FXa surface staining on mouse CD115+ splenocytes grown in human serum by flow cytometry after 10 minutes of stimulation; mean ± standard deviation (SD). n = 6. *P < .0062; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test vs unstimulated. (C) FXa clotting activity in the supernatant of aPL-stimulated monocytes; mean ± SD. n = 3. *P < .005; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (D) Detection of TF-FVIIa vs TF-FVIIa-Xa-TFPI on TF-expressing CHO-cells by αVIIa-3G1247 and 9D4 vs 12C7. (E) Coagulation inhibitory αVIIa-3G12 vs αFVII-12C7 reactivity on monocytic cells before and after stimulation with aPL HL5B Fab’2, which does not cause TF-FVIIa internalization. (F) β2GPI- and lipid-reactive HL7G, but not rJGG9, with sole β2GPI reactivity can induce FXa release from mouse CD115+ splenocytes; mean ± SD. n = 6.

Lipid-reactive aPLs cause rapid conformational changes in TF and increase clotting activity dependent on complement and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI).14 Unexpectedly, FXa loss of cell surface staining was not prevented by previously validated complement and PDI inhibitors14,42,43 or eliminating complement fixing activity in aPL HL5B Fab’2 fragments (Figure 1B). FXa also disappeared from ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6)-inhibited cells (Figure 1B), which mediates TF-FVIIa-integrin trafficking,44,45 indicating that FXa was not degraded after internalization with TF-FVIIa. Instead, we found that serum-free cell supernatants after stimulation with Fab’2 fragments of aPL HL5B contained FXa specifically triggering thrombin generation (Figure 1C). Calibration curves with purified FXa indicated 13 000 molecules of FXa released per monocyte, providing an estimate for TF-TFPI surface complexes participating in aPL signaling.

FVIIa in the inhibited complex was recognized by αFVIIa-12C7 (Figure 1A) with an epitope in the protease domain.46 Other FVIIa monoclonal antibodies (3G12, 9D4) only recognized free TF-FVIIa complex on CHO cells, but not the TFPI-inhibited TF-FVIIa-FXa complex (Figure 1D). Staining with monoclonal αFVIIa-3G1247 showed that aPL Fab’2 fragments rapidly exposed the epitope only accessible on free TF-FVIIa (Figure 1E). We have previously shown that aPL HL7G, which reacts with both cardiolipin and β2GPI, rapidly induces TF activity similar to HL5B.14 HL7G, but not aPL rJGG9 reactive with β2GPI alone, also dissociated FXa independent of complement, PDI, and ARF6 (Figure 1F). We conclude that lipid-reactive aPLs can trigger initial thrombin generation by a novel mechanism of simply dissociating FXa from cell surface localized TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI.

We imaged TF with antibodies (αTF 5G948 and αTF 10H1048,49 ) to structurally defined, adjacent epitopes exposed in TF-FVIIa.48,49 Both antibodies neither disrupted FXa binding on monocytes nor prevented aPL-induced cell surface FXa dissociation (Figure 1B), suggesting that aPLs did not directly interact with TF. Akin to the results with epitope-specific αVIIa, the epitope of αTF 10H10 was only exposed after dissociation of FXa with Fab’2 or IgG of aPL HL5B (Figure 2A). Because αTF 10H10 prevents aPL-induced conversion of TF to a procoagulant form,14 these data indicated that TF was present in a low activity conformation in the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex before aPL activation. In addition, no internalization of TF or aPL was observed after binding of αTF 10H10 (Figure 2A), which is in line with protection from pregnancy loss by this antibody in humanized TF mice.24

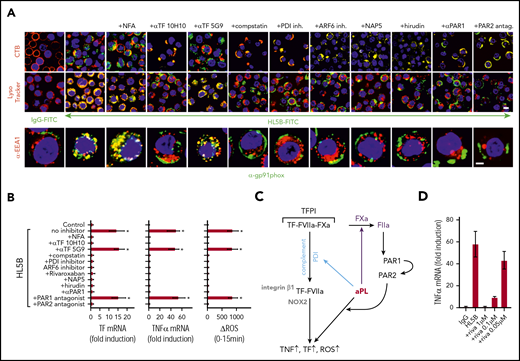

Endogenous TFPI is required for aPL internalization. Internalization of MM1 cell surface TF (A) and FVIIa (B) after 15 minutes of live cell stimulation with fluorophore-labeled aPL HL5B (IgG or Fab’2 fragment). Scale bar = 5 µm. (C) Schematic representation of complement-dependent and independent pathways initiated by aPL. (D) Flow cytometry detection of TF expression on CD115+ spleen monocytes for myeloid cell-deleted TFPI Kunitz 1 domain (TFPIΔK1) mice and littermate wild-type (WT) controls under basal conditions and after 3 hours of stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS. Note that basal and LPS-induced TF expression was not affected by TFPI mutation. (E) FXa surface localization detected by flow cytometry on CD115+ splenocytes of TFPIΔK1 and littermate WT mice. (F) Live cell imaging of aPL HL5B internalization in TFPIΔK1 monocytes after stimulation with aPL HL5B. (G) Expression of TFPI isoforms by blood monocytes isolated from WT mice detected by RT-PCR with isoform-specific primers; mean ± SD. n = 4. (H) Dose titration of aPL HL5B binding to dry milk-blocked plates coated with 2 µg/mL soluble TF1-218,88 FVIIa, TFPIα47, or FXa. (I) Effect of aPL HL5B (500 nM) on TFPIα (10 nM) inhibition of FX (100 nM) activation by 0.5 nM TF in 60% phosphatidylcholine/40 sphingomyelin56 with 1 nM FVIIa. (J) Effect of 100 µg/mL HL5B on TFPIα (50 nM) complex formation with 1 µM soluble TFGCN4,89 3 nM FVIIa, and 2 nM FXa measured by amidolytic assay with Spectrozyme FXa.

Endogenous TFPI is required for aPL internalization. Internalization of MM1 cell surface TF (A) and FVIIa (B) after 15 minutes of live cell stimulation with fluorophore-labeled aPL HL5B (IgG or Fab’2 fragment). Scale bar = 5 µm. (C) Schematic representation of complement-dependent and independent pathways initiated by aPL. (D) Flow cytometry detection of TF expression on CD115+ spleen monocytes for myeloid cell-deleted TFPI Kunitz 1 domain (TFPIΔK1) mice and littermate wild-type (WT) controls under basal conditions and after 3 hours of stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS. Note that basal and LPS-induced TF expression was not affected by TFPI mutation. (E) FXa surface localization detected by flow cytometry on CD115+ splenocytes of TFPIΔK1 and littermate WT mice. (F) Live cell imaging of aPL HL5B internalization in TFPIΔK1 monocytes after stimulation with aPL HL5B. (G) Expression of TFPI isoforms by blood monocytes isolated from WT mice detected by RT-PCR with isoform-specific primers; mean ± SD. n = 4. (H) Dose titration of aPL HL5B binding to dry milk-blocked plates coated with 2 µg/mL soluble TF1-218,88 FVIIa, TFPIα47, or FXa. (I) Effect of aPL HL5B (500 nM) on TFPIα (10 nM) inhibition of FX (100 nM) activation by 0.5 nM TF in 60% phosphatidylcholine/40 sphingomyelin56 with 1 nM FVIIa. (J) Effect of 100 µg/mL HL5B on TFPIα (50 nM) complex formation with 1 µM soluble TFGCN4,89 3 nM FVIIa, and 2 nM FXa measured by amidolytic assay with Spectrozyme FXa.

Tracking cell surface TF with αTF 5G9 furthermore showed that stimulation with Fab’2 fragments of aPL HL5B without complement fixing activity failed to induce TF internalization. In contrast, TF colocalized intracellularly with IgG of the same aPLs (Figure 2A). In addition, FVIIa and aPLs internalization required complement, PDI, and ARF6 and was blocked by αTF 10H10 (Figure 2B), which also inhibits TF-FVIIa integrin interaction required for endosomal trafficking.44,50 Thus, aPLs first dissociate the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex and then promote TF-FVIIa and aPL endosomal trafficking dependent on complement-triggered thiol-disulfide exchange (Figure 2C).

We reasoned that glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored TFPI capable of recycling the TF complex51 inhibited monocyte cell surface TF. Monocytes with myeloid cell-specific deletion of the TFPI Kunitz 1 domain (TfpiΔK1) expressed normal levels of TF (Figure 2D), but in accord with endogenously synthesized TFPI mediating complex formation, no FXa was detected on the cell surface of TfpiΔK1 monocytes (Figure 2E). Although aPL HL5B bound to the cell surface, it did not internalize in TfpiΔK1 monocytes (Figure 2F). In the mouse, 3 distinct TFPI isoforms are generated by alternative splicing,52,-54 and blood monocytes expressed TPFIα, TPFIβ, and TPFIγ (Figure 2G). Because all isoforms express Kunitz domain 1 required for TF-FVIIa-FXa complex formation and thrombosis inhibition,32 TFPI isoform-specific knock-out mice will be required to define the relevant isoform mediating monocyte TF inhibition. Thus, aPL binding to cells is insufficient for aPL internalization, which also requires coagulation activation by FXa dissociated from a cell surface-localized TF-FVIIa complex with monocyte-synthesized TFPI.

Although a previous study suggested that aPL stimulates FXa generation by interaction with TFPI,55 we found no evidence that lipid-reactive aPL HL5B bound to purified components of the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex directly (Figure 2H). Monitoring TFPIα inhibition of phosphatidylcholine/sphingomyelin-relipidated56 TF-FVIIa-dependent FX activation (Figure 2I) or of FVIIa and FXa in a soluble TF system monitored with a chromogenic substrate56 (Figure 2J) also provided no evidence that aPL HL5B disrupted TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI directly. Thus, lipid-reactive aPLs specifically dissociate the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex on viable cells.52,53

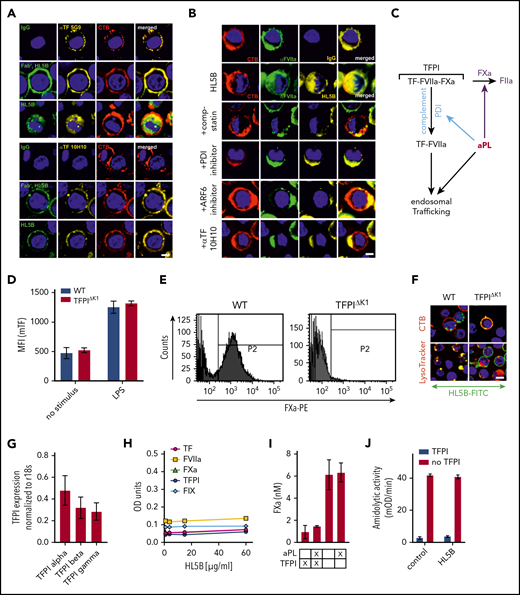

aPLs induce thrombin-dependent endosomal internalization of NADPH oxidase by the TF-FVIIa complex

Lipid-reactive aPLs induce proinflammatory cytokines dependent on endosomal ROS generation.17 We therefore evaluated how TF-FVIIa endosomal trafficking regulated ROS production. All blockers of TF-FVIIa internalization prevented NADPH oxidase subunit Gp91phox translocation into EEA1+ endosomes of human monocytes (Figure 3A). Internalization of aPLs and Gp91phox was also inhibited by αTF 10H10, which blocks TF-FVIIa integrin interaction44 and internalization, but not the noninhibitory αTF 5G9. As expected, blockade of endosomal ROS generation with niflumic acid prevented tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and TF mRNA induction by aPLs (Figure 3B) without inhibiting internalization of Gp91phox or aPL (Figure 3A). The proinflammatory responses were similarly absent when TF and aPL internalization was blocked with complement, PDI, ARF6 inhibitors, and αTF 10H10, but not αTF 5G9 (Figure 3B). Thus, aPLs, TF-FVIIa, and NADPH oxidase traffic by the same mechanism to the endosome.

aPLs induce thrombin-dependent NADPH oxidase endosomal internalization by the TF-FVIIa-integrin complex in human monocytes. (A) Live cell imaging of HL5B (green) internalization after 15 minutes and HL5B-mediated NOX2 (gp91phox, green) trafficking into the endosome after 30 minutes in the presence of indicated inhibitors. Nuclei were stained in blue with Hoechst 33342 or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, surface membrane with cholera toxin B (CTB), endo-lysosomes with Lysotracker or αEEA1 (red). Scale bar = 10 µm (upper panels) or 5 µm (lower panel). (B) TF and TNFα mRNA expression and ROS production by MM1 cells treated as indicated; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test compared with control sample. (C) Schematic representation of aPL-induced PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling linked to TF-VIIa-integrin complex trafficking. (D) Dose response of rivaroxaban inhibition of aPL HL5B-induced TNFα expression by MM1 cells.

aPLs induce thrombin-dependent NADPH oxidase endosomal internalization by the TF-FVIIa-integrin complex in human monocytes. (A) Live cell imaging of HL5B (green) internalization after 15 minutes and HL5B-mediated NOX2 (gp91phox, green) trafficking into the endosome after 30 minutes in the presence of indicated inhibitors. Nuclei were stained in blue with Hoechst 33342 or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, surface membrane with cholera toxin B (CTB), endo-lysosomes with Lysotracker or αEEA1 (red). Scale bar = 10 µm (upper panels) or 5 µm (lower panel). (B) TF and TNFα mRNA expression and ROS production by MM1 cells treated as indicated; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test compared with control sample. (C) Schematic representation of aPL-induced PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling linked to TF-VIIa-integrin complex trafficking. (D) Dose response of rivaroxaban inhibition of aPL HL5B-induced TNFα expression by MM1 cells.

Because PAR2 is required for the pathogenic effects of aPLs in mice,24 we assumed that FXa released by aPLs from the TF complex cleaved PAR2. Although extracellular FXa inhibition with the cell impermeable inhibitor NAP5 indeed prevented internalization, specific blockade of thrombin with hirudin was unexpectedly also effective (Figure 3A). The amino-terminus of thrombin-cleaved PAR1 can serve as a ligand for PAR2 in heterodimer signaling37,57,58 (Figure 3C). Although this pathway has not been implicated in aPL signaling before, inhibition of PAR1 cleavage by well-characterized monoclonal antibodies37 and an antagonist blocking the binding pocket of PAR2 prevented aPL internalization (Figure 3A). Further supporting that FXa released by aPLs triggered thrombin PAR1/PAR2 cross-activation relevant for aPL signaling, FXa inhibitors, the thrombin inhibitor hirudin, PAR1 cleavage-blocking antibodies, and a PAR2, but not PAR1, antagonist prevented aPL HL5B induction of TNFα, TF, and ROS production (Figure 3B).

A recent randomized trial indicated that the direct FXa inhibitor rivaroxaban was less efficient than vitamin K antagonists in preventing arterial thrombotic events in severe APS.59 We find that rivaroxaban in excess of 100 nM was required to inhibit aPLs signaling completely (Figure 3D), suggesting that pharmacokinetic fluctuations in drug levels may limit the effectiveness of FXa inhibitors in blocking aPL-induced signaling.

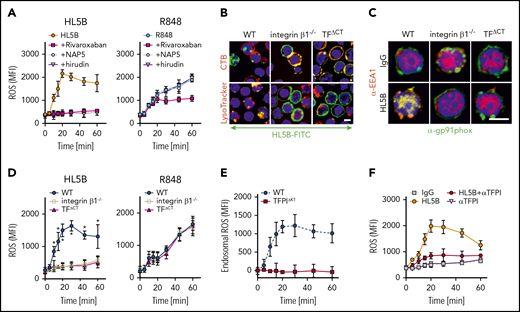

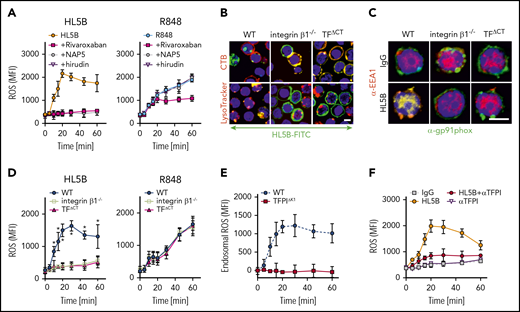

Lipid-reactive aPLs induce PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling and TF-integrin trafficking in mouse cells

ARF6 inhibitors and αTF-10H10, which both interfere with integrin function, blocked NADPH oxidase activation, suggesting that aPL signaling requires a TF-integrin complex. As seen with aPL-stimulated human cells, ROS production was completely blocked by FXa inhibitors rivaroxaban (>100 nM) and NAP5 and thrombin inhibitor hirudin in mouse spleen-derived monocytes (Figure 4A). In contrast, ROS production induced by TLR7/8 agonist R848 was not blocked by NAP5 and hirudin, but continuing ROS production was suppressed by the cell-permeable FXa inhibitor rivaroxaban. These data demonstrate that cell surface proteases specifically initiate aPL signaling responses.

NADPH oxidase internalization by the TF-integrin β1 complex. (A) Time course of ROS production measured in WT CD115+ spleen monocytes preloaded with H2DCFDA stimulated with aPL HL5B or the TLR7/8 ligand R848 in the presence of the indicated coagulation protease inhibitors; mean ± SD. n = 6. (B) Live cell imaging of aPL HL5B internalization in CD115+ cells of the indicated mouse strains. Scale bar = 5 µm. (C) Catalytic subunit of NOX2 (gp91phox) colocalization with EEA1+ endosomes in CD115+ spleen cells from integrin β1−/− and TFΔCT mice. Scale bar = 5 µm. (D) Quantification of ROS production in CD115+ splenocytes of the indicated mouse strains after stimulation with aPL HL5B or TLR7/8 agonist R848; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P = .0001; 2-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (E) TFPI is required for endosomal ROS production. ROS generation in TFPIΔK1 or WT monocytes was measured after stimulation with aPL HL5B in the presence or absence of niflumic acid (0.1 mM). Endosomal ROS production after subtraction of nonendosomal ROS measured in the presence of niflumic acid is shown; mean ± SD. n = 4. (F) ROS production was measured in cells preloaded with H2DCFDA in human monocytes stimulated with HL5B either alone or in the presence of αTFPI (20 µg/mL) added 15 minutes before aPL stimulation; mean ± SD. n = 6.

NADPH oxidase internalization by the TF-integrin β1 complex. (A) Time course of ROS production measured in WT CD115+ spleen monocytes preloaded with H2DCFDA stimulated with aPL HL5B or the TLR7/8 ligand R848 in the presence of the indicated coagulation protease inhibitors; mean ± SD. n = 6. (B) Live cell imaging of aPL HL5B internalization in CD115+ cells of the indicated mouse strains. Scale bar = 5 µm. (C) Catalytic subunit of NOX2 (gp91phox) colocalization with EEA1+ endosomes in CD115+ spleen cells from integrin β1−/− and TFΔCT mice. Scale bar = 5 µm. (D) Quantification of ROS production in CD115+ splenocytes of the indicated mouse strains after stimulation with aPL HL5B or TLR7/8 agonist R848; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P = .0001; 2-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (E) TFPI is required for endosomal ROS production. ROS generation in TFPIΔK1 or WT monocytes was measured after stimulation with aPL HL5B in the presence or absence of niflumic acid (0.1 mM). Endosomal ROS production after subtraction of nonendosomal ROS measured in the presence of niflumic acid is shown; mean ± SD. n = 4. (F) ROS production was measured in cells preloaded with H2DCFDA in human monocytes stimulated with HL5B either alone or in the presence of αTFPI (20 µg/mL) added 15 minutes before aPL stimulation; mean ± SD. n = 6.

TF-FVIIa interacts with heterodimers of integrin β1,44 and the TF cytoplasmic domain regulates ROS production.24,60 In the absence of integrin β1 or the TF cytoplasmic domain, aPL HL5B neither internalized (Figure 4B) nor caused Gp91phox translocation into EEA1+ endosomes (Figure 4C). Accordingly, stimulation with aPLs failed to induce ROS in monocytes from TF cytoplasmic domain-deleted (TFΔCT) or integrin β1-deficient mice, but ROS production was not affected when the same cells were stimulated directly with TLR7/8 agonist (Figure 4D). Thus, the TF-integrin complex specifically directs ROS production by aPLs to the endosome. In addition, endosomal ROS production was abolished in TfpiΔK1 monocytes (Figure 4E) and by TFPI antibody blockade of human monocytes (Figure 4F), which do not express TFPIγ present in mouse,52 confirming that aPLs induce a species-conserved endosomal signaling pathway.

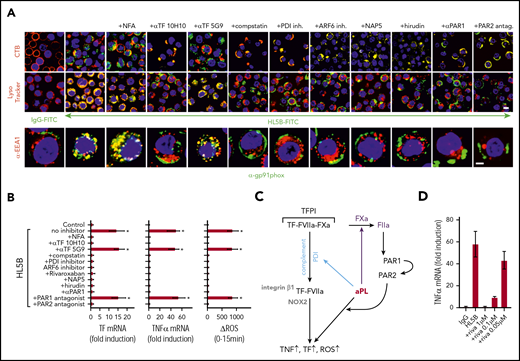

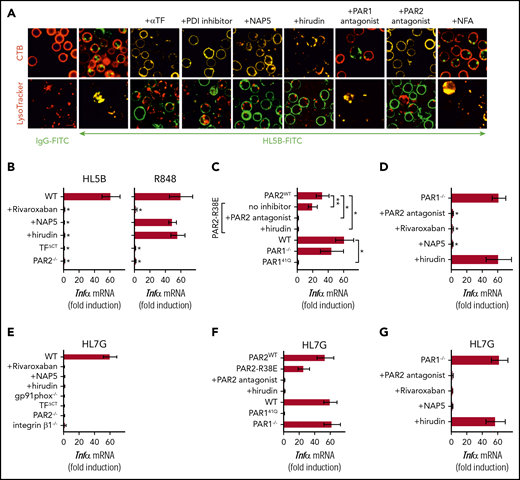

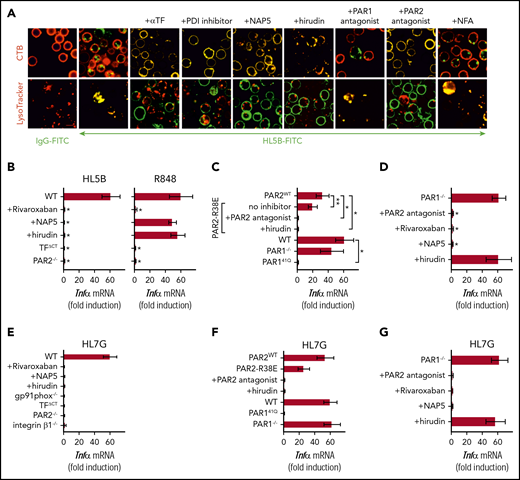

As seen in human monocytes, aPL internalization in mouse monocytes was also blocked by αTF and inhibitors of PDI, complement, FXa, and thrombin (Figure 5A). The cell-impermeable inhibitors NAP5 and hirudin prevented induction of TNFα by aPLs, but not by TLR7/8 agonism in mouse cells (Figure 5B). However, the cell-permeable FXa inhibitor rivaroxaban and deficiency of PAR2 or the TF cytoplasmic domain markedly inhibited induction of TNFα by both aPLs and TLR7/8 agonism (Figure 5B). Thus, PAR2 and TF are not only required for cell surface aPL signaling but also, more broadly, participate in myeloid cell endosomal TLR signaling.

Lipid-reactive aPLs induce PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling. (A) WT C57BL/6J mononuclear cells were treated for 15 minutes with the indicated inhibitors and stimulated for 15 minutes with FITC-labeled IgG or aPL HL5B for live cell imaging. (B) TF-thrombin-dependent Tnfα mRNA induction by aPL signaling in mouse CD115+ splenocytes; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test compared with WT sample. (C-D) Tnfα mRNA induction by aPL HL5B normalized to control IgG stimulated cells in PAR1−/−, PAR1, or PAR2 cleavage-resistant spleen mononuclear cells with the indicated inhibitors; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; **P = .044; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (E-G) Tnfα mRNA induction after 3 hours of stimulation with aPL HL7G in CD115+ spleen monocytes from WT mice or the indicated mouse strains treated with the indicated inhibitors.

Lipid-reactive aPLs induce PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling. (A) WT C57BL/6J mononuclear cells were treated for 15 minutes with the indicated inhibitors and stimulated for 15 minutes with FITC-labeled IgG or aPL HL5B for live cell imaging. (B) TF-thrombin-dependent Tnfα mRNA induction by aPL signaling in mouse CD115+ splenocytes; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test compared with WT sample. (C-D) Tnfα mRNA induction by aPL HL5B normalized to control IgG stimulated cells in PAR1−/−, PAR1, or PAR2 cleavage-resistant spleen mononuclear cells with the indicated inhibitors; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .0001; **P = .044; 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett multiple-comparison test. (E-G) Tnfα mRNA induction after 3 hours of stimulation with aPL HL7G in CD115+ spleen monocytes from WT mice or the indicated mouse strains treated with the indicated inhibitors.

Antibodies to human PAR1 showed that extracellular PAR1 cleavage was required for aPL signaling (Figure 3A-B), but only PAR2−/− and not PAR1−/− mice were protected from aPL-induced pregnancy loss.24 Consistent with cross-activation of PAR2 by thrombin-cleaved PAR1, only direct PAR2, but not PAR1, antagonists prevented aPL internalization in mouse monocytes (Figure 5A). Thrombin PAR1/PAR2 cross-activation does not require PAR2 cleavage, but the signaling scaffold of PAR2, which is deleted in PAR2−/− mice. In contrast to PAR2−/− cells, TNFα induction by aPL HL5B was largely preserved in knock-in mutant cells carrying a cleavage-resistant PAR2 receptor (PAR2 R38E mice)34 (Figure 5C). PAR2 antagonist and the thrombin inhibitor hirudin blocked proinflammatory effects of aPLs in PAR2 R38E cells, confirming PAR2 cross-activation by thrombin-cleaved PAR1. Furthermore, thrombin-insensitive PAR1 R41Q mutant cells35 failed to respond to HL5B stimulation, whereas in accord with prior studies, PAR1−/− mice were activated normally (Figure 5C).

To resolve the unexplained response of PAR1−/− cells, we analyzed the proteases involved in aPL signaling. These experiments revealed that aPL signaling in PAR1−/− cells became insensitive to thrombin inhibition with hirudin, while remaining sensitive to FXa inhibitor and PAR2 antagonist (Figure 5D). Thus, deletion of PAR1 enabled FXa-PAR2 signaling, and thereby obscured the identification of thrombin-induced PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling as a central pathway of aPL pathology. Importantly, this protease-dependent aPL signaling pathway is conserved between mice and humans.

Analysis of human monoclonal aPLs identified 3 distinct antigen specificities; that is, reactivity with diagnostic cardiolipin alone, reactivity with β2GPI, and dual reactivity with both lipid and β2GPI.10,14,26,27 Whereas β2GPI-reactive aPLs (rJGG9) failed to rapidly induce TF clotting activity in monocytes and ROS-dependent signaling, the dual-reactive aPLs HL7G was comparable with aPL HL5B in this respect.14,17 Remarkably, the dual-reactive HL7G triggered the same pro-inflammatory pathway requiring endosomal signaling dependent on the TF cytoplasmic domain, integrin β1 (Figure 5E), and thrombin-PAR1/PAR2 cross-activation (Figure 5F-G). Thus, acquisition of β2GPI reactivity in cross-reactive aPLs preserved signaling specificity delineated for lipid-reactive aPL HL5B.

Myeloid cell TFPI is required for aPL-induced thrombosis

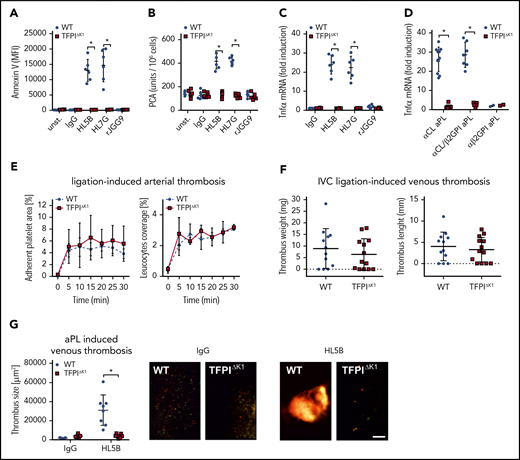

TFΔCT mice with defective endosomal ROS production and aPL translocation have previously been shown to be protected from pregnancy loss,24 and endosomal ROS production is required for aPL-induced thrombosis.13 As shown here, endosomal aPL signaling was also dependent on formation of the TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI complex that, on dissociation induced complement- and PDI-dependent trafficking of TF-FVIIa. Although TfpiΔK1 monocytes expressed normal levels of TF antigen (Figure 2D), aPL stimulation of these cells failed to rapidly induce cell surface phosphatidylserine exposure (Figure 6A) and, importantly, TF clotting activity (Figure 6B), as well as upregulation of TNFα mRNA (Figure 6C). In addition, we analyzed 20 randomly selected patient IgG fractions representative of diagnostic reactivities found in general patient populations with APS.10,14 Rare aPL IgG reactive with β2GPI alone (α-β2GPI; 2/20 patients) did not induce TNFα mRNA, but signaling of lipid-reactive aPL IgG (defined by cardiolipin reactivity, α-CL) with (similar to HL7G; 7/20 patients) or without (similar to HL5B; 11/20 patients) β2GPI cross-reactivity was markedly reduced in TfpiΔK1 monocytes (Figure 6D) These data not only established a supportive effect of TFPI in myeloid cell endosomal signaling in vitro but also predicted a paradoxical prothrombotic role for TFPI in aPL-induced thrombosis.

Myeloid cell TFPI is required for aPL-induced thrombosis. (A-B) Murine CD115+ monocytes of control or TFPIΔK1 mice were stimulated for 10 minutes with aPLs (100 ng/mL) and then analyzed for PS exposure by Annexin V–FITC binding in flow cytometry (A) or clotting activity (B); mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (C) Induction of TNFα mRNA in CD115+ spleen monocytes stimulated for 1 hour with the indicated aPLs; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (D) TNFα induction by IgG fractions isolated from 20 patients with APS in WT and TFPIΔK1 mice stimulated for 1 hour. APS patient IgG samples can be divided into 3 groups: patient IgG that binds only to cardiolipin in a cofactor-independent manner similar to HL5B (αCL; n = 11); patient IgG that binds to both antigens, similar to HL7G (αCL/β2GPI; n = 7); and patient IgG that binds only to β2GPI, similar to rJGG9 (αβ2GPI; n = 2). *P < .0001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (E) Ligation-induced arterial thrombosis in littermate TFPIΔK1 (n = 8) and TFPIK1flfl control animals (n = 5). (F) Inferior vena cava ligation-induced venous thrombosis in littermate TFPIΔK1 (n = 9) and TFPIK1flfl control animals (n = 9) 48 hours after flow restriction. No thrombus developed in 4 and 3 animals, respectively. (G) HL5B-amplified thrombosis analyzed in the flow-restricted vena cave inferior of the indicated mouse strains vs isotype control antibody; mean ± SD. *P = .007; t-test after Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution. HL5B: TFPIK1flfl control mice, n = 8; TFPIΔK1 mice, n = 7; isotype control TFPIK1flfl control mice, n = 5; TFPIΔK1 mice, n = 5. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Myeloid cell TFPI is required for aPL-induced thrombosis. (A-B) Murine CD115+ monocytes of control or TFPIΔK1 mice were stimulated for 10 minutes with aPLs (100 ng/mL) and then analyzed for PS exposure by Annexin V–FITC binding in flow cytometry (A) or clotting activity (B); mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (C) Induction of TNFα mRNA in CD115+ spleen monocytes stimulated for 1 hour with the indicated aPLs; mean ± SD. n = 6. *P < .001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (D) TNFα induction by IgG fractions isolated from 20 patients with APS in WT and TFPIΔK1 mice stimulated for 1 hour. APS patient IgG samples can be divided into 3 groups: patient IgG that binds only to cardiolipin in a cofactor-independent manner similar to HL5B (αCL; n = 11); patient IgG that binds to both antigens, similar to HL7G (αCL/β2GPI; n = 7); and patient IgG that binds only to β2GPI, similar to rJGG9 (αβ2GPI; n = 2). *P < .0001; 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak correction. (E) Ligation-induced arterial thrombosis in littermate TFPIΔK1 (n = 8) and TFPIK1flfl control animals (n = 5). (F) Inferior vena cava ligation-induced venous thrombosis in littermate TFPIΔK1 (n = 9) and TFPIK1flfl control animals (n = 9) 48 hours after flow restriction. No thrombus developed in 4 and 3 animals, respectively. (G) HL5B-amplified thrombosis analyzed in the flow-restricted vena cave inferior of the indicated mouse strains vs isotype control antibody; mean ± SD. *P = .007; t-test after Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution. HL5B: TFPIK1flfl control mice, n = 8; TFPIΔK1 mice, n = 7; isotype control TFPIK1flfl control mice, n = 5; TFPIΔK1 mice, n = 5. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Although platelet-expressed TFPI suppresses thrombosis,32,61 we found that myeloid cell-specific inactivation of TFPI in TfpiΔK1 mice had no appreciable effect on ligation-induced arterial (Figure 6E) or myeloid cell TF-dependent41 flow-restricted venous (Figure 6F) thrombus formation. Because myeloid cell-deleted TfpiΔK1 mice showed normal venous thrombus development, we could rigorously evaluate TFPI roles in aPL-induced responses in vivo. In line with in vitro experiments, induction of thrombosis by aPL HL5B, but not control antibody, was prevented by myeloid cell-specific inactivation of TFPI in TfpiΔK1 mice (Figure 6G). Thus, the physiological role of TFPI as a regulator of TF is exploited by aPLs to induce pathological signaling and thrombosis.

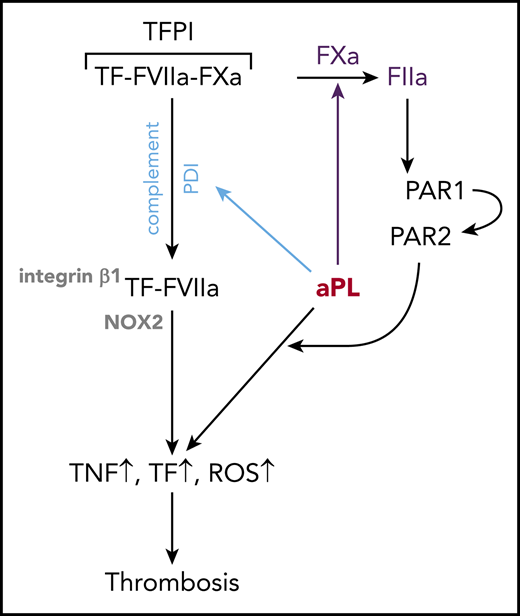

Discussion

Here we delineate proximal cellular events induced by aPLs in monocytes. Lipid-reactive aPLs with or without β2GPI cross-reactivity activate a common signaling pathway by dissociating TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI. FXa liberated on the cell surface then generates thrombin for PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling in mouse and human cells. In addition to thrombin signaling, internalization of surface-bound aPLs requires Fc-mediated activation of complement. Complement activation-associated thiol disulfide exchange presumably alters PDI function,42,62 and thereby permits TF-FVIIa trafficking that delivers the NADPH oxidase to the endosome dependent on the TF cytoplasmic domain.

The epitope of αTF-10H10 on TF-FVIIa is exposed only after aPL-induced dissociation of TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI. Because αTF-10H10 recognizes a TF cell surface pool with low procoagulant activity63 and inhibits aPL-induced allosteric activation of TF for full procoagulant activity without preventing procoagulant PS exposure,14 TF is likely in a conformation unfavorable for FXa release and favorable for formation of TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI on the cell surface. This antibody also blocks association of TF-FVIIa with integrin β164 and, similar to integrin β1-deficiency or pharmacological blockade of the ARF6 integrin trafficking pathway, prevents endosomal trafficking of aPL signaling components and aPL proinflammatory signaling.

These elucidated cellular events explain previously unconnected observations on aPL pathology. αTF-10H10 inhibits not only monocyte signaling but also TF cytoplasmic domain-dependent pregnancy complications in humanized TF mice.24 Complement activation has previously been shown to be crucial for the major pathological manifestation of APS; that is, pregnancy loss12,21,65,66 and thrombosis.14,67 It will be of interest for further studies to clarify whether aPL binding to β2GPI and clustering of LRP82,68,69 may amplify complement-dependent thrombosis41 in the interplay of platelets and immune cells.69,70

The direct FXa inhibitor rivaroxaban effectively blocked aPL signaling in vitro, but only at fairly high concentrations, which may explain the lower efficacy relative to vitamin K antagonists in preventing arterial thrombosis in severe APS.59 Important open questions remain on how standard dosing of direct oral FXa inhibitor interrupt cell signaling pathways in vivo, and interfere with the emerging roles of FXa as a cofactor activator in coagulation reactions.47,71,72

APS was originally defined on the basis of aPL reactivity with negatively charged lipids, including cardiolipin. Although lipid-reactive antibodies also transiently expand in infectious diseases,73 clonal evolution and cross-reactivity with coagulation regulatory proteins,9 including β2GPI, are correlated with the incidence of thrombotic complications.74 However, systematic meta-analysis of clinical data indicates that lipid-reactive aPLs are associated with a comparable relative risk.75 The current data with monoclonal antibodies show that lipid-reactive aPLs with β2GPI reactivity activate the same monocyte signaling pathway delineated for aPLs with sole lipid reactivity. In addition, the representative nature of these monoclonal antibodies for patient IgG10,14 is confirmed here for TFPI-dependent monocyte activation. Thus, selection for β2GPI reactivity cannot be used as an experimental approach to exclude relevant lipid-dependent signaling.68

In the diagnosis of APS, inhibition of coagulation reactions in the lupus anticoagulant assay is paradoxically predictive for clinical hypercoagulability and thrombosis risk. We here describe a direct and rapid procoagulant effect of aPLs resulting simply from dissociation of FXa in an inhibited cell surface TF complex. The ensuing thrombin-dependent signaling sets in motion aPL endosomal trafficking amplifying TF gene transcription as well as rapid conversion of cell surface TF to a procoagulant form through complement activation and PDI. Thus, unlike coagulation assays formulated with isolated lipids, cell-based assay systems that depend on early events of aPLs on TF in a multiprotein complex properly measure prothrombotic effects of aPLs.

Our data uncovered a paradoxical stimulatory role for TFPI in promoting aPL-induced signaling and TF activation on monocytes. We expected an exacerbation of aPL pathologies by inactivation of TFPI in monocytes, based on the established roles for TFPI as a regulator of TF-dependent cell signaling,76 as well as of TF77,-79 and FXa61,80,81 in hemostasis and thrombosis. Pharmacological application of TFPI also dampens tissue injury in autoimmune disease models.82 Unexpectedly, we found that genetic deletion of the first Kunitz domain of TFPI mediating interaction with FVIIa prevented not only cell surface localization of the inhibited TF complex on monocytes but also the spectrum of proinflammatory aPL signaling responses, rapid TF procoagulant activation, and aPL-induced thrombosis. Thus, the physiological inhibition of TF by TFPI primes monocytes for the pathological effects of aPLs.

The clinical significance of the proposed deregulation of TF function by aPL is supported by documented correlations of monocyte TF expression with the severity of APS.19,83,-85 TF expression by monocytes is also a risk factor for cardiometabolic disease,86,87 resulting in circulating primed monocytes for pathological aPL signaling in patients with autoimmune diseases. Thus, cardiometabolic disease risk factors may represent overlooked variables that sensitize to the pathogenic complications of APS associated with autoimmune diseases, and conversely, lipid-reactive aPLs developing transiently in acute or chronic infections may trigger acute thrombotic events in cardiovascular diseases.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Simari for providing TFPIK1flfl and Uli Müller for providing integrin β1flfl mice.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, HL060742 and HL142975), the Humboldt Foundation of Germany (Humboldt Professorship Ruf), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (BMBF 01EO1003 and 01EO1503), and the German Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M.-C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; A.H., S.R., D.G.P., D.S., C.G., C.R., S.S., and P.P. performed experiments; J.H.G. developed and characterized crucial reagents; K.J.L. designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and W.R. conceptualized the study, designed and interpreted experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wolfram Ruf, Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center, Langenbeckstr 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; e-mail: ruf@uni-mainz.de, ruf@scripps.edu; and Karl J. Lackner, Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center, Langenbeckstr 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; e-mail: karl.lackner@unimedizin-mainz.de.