Key Points

We identified new genetic loci contributing to the risk of venous thromboembolism, some of which are outside known coagulation pathways.

We provide evidence that blood traits may contribute to the underlying biology of venous thromboembolism risk.

Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality. To advance our understanding of the biology contributing to VTE, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of VTE and a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) based on imputed gene expression from whole blood and liver. We meta-analyzed GWAS data from 18 studies for 30 234 VTE cases and 172 122 controls and assessed the association between 12 923 718 genetic variants and VTE. We generated variant prediction scores of gene expression from whole blood and liver tissue and assessed them for association with VTE. Mendelian randomization analyses were conducted for traits genetically associated with novel VTE loci. We identified 34 independent genetic signals for VTE risk from GWAS meta-analysis, of which 14 are newly reported associations. This included 11 newly associated genetic loci (C1orf198, PLEK, OSMR-AS1, NUGGC/SCARA5, GRK5, MPHOSPH9, ARID4A, PLCG2, SMG6, EIF5A, and STX10) of which 6 replicated, and 3 new independent signals in 3 known genes. Further, TWAS identified 5 additional genetic loci with imputed gene expression levels differing between cases and controls in whole blood (SH2B3, SPSB1, RP11-747H7.3, RP4-737E23.2) and in liver (ERAP1). At some GWAS loci, we found suggestive evidence that the VTE association signal for novel and previously known regions colocalized with expression quantitative trait locus signals. Mendelian randomization analyses suggested that blood traits may contribute to the underlying risk of VTE. To conclude, we identified 16 novel susceptibility loci for VTE; for some loci, the association signals are likely mediated through gene expression of nearby genes.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) contributes significantly to morbidity in adults, occurring at rates of 1 to 2 events per 1000 person-years.1 Despite improved prophylaxis in high-risk patients, neither the incidence of VTE nor mortality among VTE patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) has decreased in recent decades.1,2

Many of the disease-causing mechanisms underlying VTE remain to be fully characterized, including those involving genetics. It has been >50 years since the first article linking genetic variation to the risk of VTE was published.3 With the availability of large population-based data sets and new technologies, including genome-wide association studies (GWASs), there has been a rapid accumulation of information to link genetic variation to VTE risk.4-9 To advance our understanding of the biology of VTE, which may lead to better disease risk prediction and prevention, we meta-analyzed VTE GWAS data from 18 studies. We also used tissue-specific gene expression data to impute predicted expression based on GWAS variants. With these imputed expressions, we conducted a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) of VTE.10 Additionally, we conducted colocalization analyses to assess the probability that the expression of genes near identified GWAS signals mediates the VTE associations observed in our GWASs.11 Lastly, we applied Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to better understand the role of traits that are genetically related to novel VTE loci in the development of VTE.

Methods

Setting, design, and participants

The setting for this multi-ancestry GWAS meta-analysis of VTE is the International Network Against Venous Thrombosis (INVENT) Consortium.7 The meta-analysis is based on prospective cohort and case-control data from 18 studies. Supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site) provides study-specific information for all included studies. Participants were adult men and women of European ancestry (EA) or African American ancestry (AA). Cases experienced a VTE, either deep vein thrombosis or PE. Supplemental Table 1 provides details about case definitions across the 18 studies. Supplemental Table 1 also provides information on the selection of controls for case-control and cohort analyses, when applicable. All participants provided informed consent for use of their genetic and health information for analysis.

Study-specific analyses, meta-analyses, and replication

Before transancestry meta-analysis, additional quality control of the study-specific GWAS summary statistics was conducted according to previously published protocols.12

Summary descriptions of study-specific genotyping arrays, quality control filtering, and imputation methods are shown in supplemental Table 1. Variant-specific analyses of the association between allele dosage and VTE risk were performed separately in each study using an additive genetic model and either logistic or Cox-proportional regression analyses adjusted for study-specific covariates and participant relatedness, when applicable (supplemental Table 1). Chromosome X variants located in the pseudo-autosomal regions were excluded. For each study, we also excluded variants with imputation quality score r2 < 0.3 (<0.7 for eMERGE),13 as well as variants with a minor allele count < 20 in either case or control counts. For the EA autosomal data, we also excluded variants with minor allele frequencies (MAFs) that differed between our data sets and the 1000 Genomes Project or the Haplotype Reference Consortium according to the following formula: ,14 where p0 and p1 are the MAFs in the 1000 Genomes Project (or Haplotype Reference Consortium) and our data sets, respectively.

For autosomal chromosomes, meta-analysis was conducted using a fixed-effects inverse-variance weighting as implemented in METAL.15 For the X chromosome, we conducted sex-specific meta-analysis using fixed-effects inverse-variance weighting and then used 2 approaches to combine the results from men and women: fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis and sample-size weighted meta-analysis based on P values and effect direction.16,17 Across all GWAS analyses, P < 5 × 10−8 was considered genome-wide significant.18,19 We only included variants that were observed in ≥3 studies. We also conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by ancestry: EA and AA.

To search for additional independent genome-wide significant variants at a particular locus, we conducted conditional analyses using GCTA COJO software.20,21 For these analyses, a set of 9330 individuals from 4 studies with genotypes from the Illumina OmniExpress array imputed to 1000 Genomes Project was used to create a linkage disequilibrium (LD) reference panel.22 The conditional analyses were conducted using the EA results only.

For novel variants meeting genome-wide significance, we extracted information from published GWASs on 10 hemostasis traits to characterize associations with intermediate phenotypes: fibrinogen,23 fibrin D-dimer,24 coagulation factor VII,25 coagulation factor VIII (FVIII),26 coagulation factor XI,27 and von Willebrand factor (VWF),26 tissue plasminogen activator,28 plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1,29 activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT),30 and prothrombin time.30

Genome-wide significant findings were then replicated using VTE GWAS data from the Department of Veterans Affairs Million Veteran Program (MVP), which included 11 029 cases and 235 202 controls.31 For replication, we considered a P < .05 divided by the number of variants tested as statistically significant. In addition, the direction of the association was required to be the same in the discovery and replication data.

Previously reported variants associated with VTE

As a follow-up to the agnostic GWASs, we assessed the association of common (MAF > 0.01) candidate VTE variants previously reported with high-quality evidence in the literature but not reaching genome-wide significance in the GWASs. The level of significance was set as 0.05 divided by the number of tests.

Heritability and genetic risk score

We calculated the heritability on the observed scale due to genotyped variants as previously defined using nested case-control data on 6 184 VTE cases and 19 337 controls in UK Biobank.32 For these analyses, we only included genotyped variants and excluded those with MAF < 0.01 and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P < .01. We additionally excluded subjects so that no pair of individuals had a relatedness coefficient > 0.025, as calculated by the GCTA software.33 Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, array, and top 10 principal components. We calculated the heritability on the liability scale assuming a disease prevalence of 0.5%.34

We also calculated a genetic risk score (GRS) to summarize the risk for each individual according to the number of risk alleles carried.35 The GRS was calculated in 6 573 VTE cases and 20 515 controls in UK Biobank; UK Biobank was selected for the GRS because the study was the largest and we had easy access to individual-level data, which are required for the GRS. Therefore, the GRS analysis was restricted to the EA individuals. To minimize overfitting, we reran the EA meta-analysis for the included variants excluding this set of UK Biobank cases and controls to obtain log odds ratio (β) estimates. For each individual j, the GRS was calculated as , where k is the number of selected variants, is the log odds ratio for variant i based on the aforementioned meta-analysis, and is the number of risk alleles of variant i that individual j is carrying. The GRS was then standardized to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. We assessed the association between the GRS and VTE risk using logistic regression, adjusting for sex and age at the time of interview.

In silico bioinformatics, eQTL expression, TWASs, and colocalization analyses

We used HaploReg (version 4.1) to describe any predicted functional aspects of the lead variants in the newly identified GWAS regions.36 We conducted a TWAS of VTE using 4 gene expression datasets: 1 from liver tissue (Genotype-Tissue Expression [GTEx] version 7, N = 153) and 3 from whole blood (GTEx version 7, N = 369; Young Finns Study [YFS], N = 1414; and the Netherlands Twin Registry [NTR], N = 1247).10,37,38 Gene expression prediction models for YFS and NTR were downloaded from http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/. Using the 2 GTEx data sets as training data, we used the FUSION pipeline to construct gene expression prediction models based on each gene’s local variants (as described previously).10 We only considered cis variants, those located within 500 kb of the gene of interest. For the YFS and NTR data sets, gene expression models were created using 5 approaches: single best expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL), elastic net, lasso, Bayesian sparse linear mixed model, and best linear unbiased predictor.10 For the 2 GTEx data sets, we limited the models to the single best eQTL, elastic net, and lasso for computational feasibility. We only included genes whose expression showed evidence of a significant heritable component (P < .01). In total, we successfully obtained gene expression prediction models for 15 982 genes across the 4 data sets; some genes are counted multiple times because we successfully generated gene expression imputation models for that gene in multiple reference data sets. These variant-based gene expression prediction models were then assessed in the EA VTE GWAS to estimate the association between imputed gene expression and VTE.10 We only included VTE results from the EA analysis because the method relies on LD patterns generated from the 1000 Genomes Project EA population. We considered associations with P < 3.13 × 10−6 (0.05/15 982 genes) statistically significant.

We also conducted colocalization analysis using the coloc pipeline.11 Details are provided in the supplemental Methods. Briefly, coloc is a Bayesian approach to estimate the probability that 2 observed association signals (here GWAS and eQTL) in a given locus are consistent with a shared causal variant. Coloc calculates the posterior probability for 5 scenarios, 1 of which represents a shared causal variant modifying gene expression and phenotype. A high posterior probability for this scenario indicates a shared eQTL-VTE GWAS signal, suggesting that the VTE association is mediated by gene expression of the gene of interest.

MR analyses of selected traits and VTE

We reviewed the published literature to search for other traits associated with the newly identified VTE genetic loci, and these associations are reported. Then, to better understand the association of these traits with VTE, we conducted MR analysis of the associated traits and VTE. Identified associated traits needed to have GWAS summary results available to conduct the MR analysis. We obtained the effect allele, trait-specific association estimates, and standard errors for variants from the trait’s GWAS summary results. Because we obtained GWAS summary results for the traits from UK Biobank, we reran the VTE GWAS excluding UK Biobank to avoid sample overlap. We then extracted VTE-specific effect estimates and P values from the EA VTE GWAS for each of the variants. We conducted 2-sample MR analyses to estimate the association between traits and VTE using summary genetic association statistics, as described previously.39,40 We also conducted sensitivity analysis using MR Egger and weighted median regression.41,42

Results

GWAS genome-wide significant associations

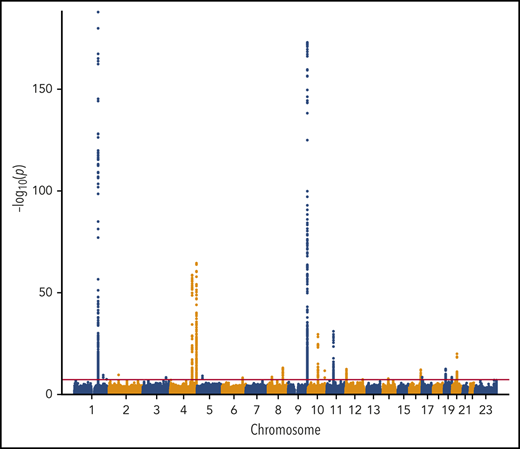

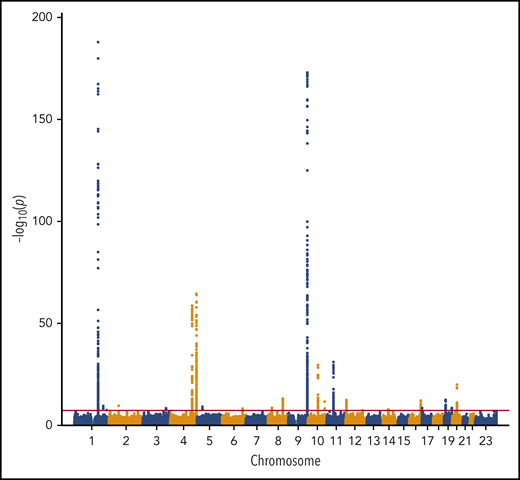

We performed a transancestry meta-analysis based on 18 studies, which included 30 234 VTE cases (29 435 EA and 799 AA), 172 122 controls (157 769 EA and 14 353 AA), and 12 923 718 variants across 23 chromosomes. The genomic inflation factor for the meta-analysis was 1.08 (supplemental Figure 1), an elevation likely due to a polygenic signal (the intercept from LD score regression was 1.03).43 We identified 33 independent signals across 24 genetic loci that reached genome-wide significance (Figure 1; Table 1). In addition, we performed ancestry-stratified analyses (supplemental Table 2) and identified 1 additional locus at 17p13.1, which was genome-wide significant in the EA meta-analysis but not in the transancestry meta-analysis (Table 1). Across the 34 independent genome-wide significant signals, 14 are newly reported associations; 11 are in newly associated loci, and 3 are in previously characterized genes. In “Novel VTE-associated Loci,” we describe the newly associated loci, the details of which are found in Table 1; supplemental Table 2 provides details of ancestry-stratified results. Supplemental Tables 3 and 4 provide ancestry-stratified results for all of the variants with P values < 1.0 × 10−6. Supplemental Table 5 presents replication results in MVP; given 11 novel associations, the threshold for replication was 0.05/11 = 0.0045. Supplemental Table 6 presents associations of the novel top variants with the 10 hemostasis traits. Variant-specific regional plots are provided in supplemental Figure 2, and forest plots are shown in supplemental Figure 3.

Manhattan plot of the association of 12 923 718 variants by chromosome and their association with VTE.

Manhattan plot of the association of 12 923 718 variants by chromosome and their association with VTE.

Novel VTE-associated loci

Chr1.q42.2

We identified a novel association with an intronic variant (rs145470028) in open reading frame C1orf198 (P = 3.0 × 10−8; odds ratio [OR], 0.78). The variant T allele was uncommon (MAF 0.02 in EA and absent in AA) and is located in an enhancer region marked with H3K4me1 and H3K27ac in liver tissue. The association did not replicate (P = .6) in the MVP data set and was not associated with any of the 10 hemostasis phenotypes (P > .05 for all associations).

Chr2.p14

We identified a novel association with rs1867312 (P = 2.5 × 10−10; OR, 1.06), intronic to PLEK and located in multiple histone marks in blood. The association was replicated (P = 1.9 × 10−4) and the minor allele (C) was associated with higher plasma FVII. Another PLEK variant (rs13011075) in moderate LD with rs1867312 (r2 = 0.3) has been associated with mean corpuscular volume but not with our VTE variant.44 Variant rs13011075 showed a nominal association with VTE (OR, 1.04; P = 1.2 × 10−4). The transcribed protein of PLEK, pleckstrin, is found in platelets and is involved with platelet biology.45,46

Chr5.p13.1

We identified a common intronic variant (rs4869589) in OSMR-AS1 (P = 7.6 × 10−10; OR, 1.07), the antisense gene to OSMR, the oncostatin M receptor. This variant is located in a region with enhancer histone marks H3K4me1 and H3K27ac in liver tissue. The association was replicated (P = 2.4 × 10−6) and was not associated with any of the 10 hemostasis traits. Variants in OSMR have been associated with amyloidosis, but there are no reported associations of its antisense gene with human traits.47

Chr8.p21.1

We identified a common intronic variant (rs12675621) in NUGGC (P = 2.4 × 10−9; OR, 1.07); NUGGC (nuclear GTPase, germinal center associated) is not known to be associated with hemostasis or thrombosis phenotypes. The association was not replicated (P = .62), and its proxy’s minor allele (rs1716157; r2 = 0.97, D′ = 0.98) was associated with greater prothrombin time. The variant is 48 kb upstream from SCARA5 (scavenger receptor class A member 5), in which the rs2726953 (intronic) variant has been associated with plasma levels of VWF but not previously with VTE.48,49 The LD between rs12675621 and rs2726953 is limited (r2 = 0.04, D′ = 0.20). The rs2726953 variant was associated with VTE (P = 2.6 × 10−5; OR, 1.05) in the current meta-analysis and appears to be an independent signal in regional association plots (supplemental Figure S2i).

Chr10.q26.11

We identified a novel association with the rs10886430 variant, intronic to GRK5 (P = 2.2 × 10−12; OR, 1.12), a G protein–coupled receptor for kinase 5. The association replicated (P = 6.7 × 10−11), and the variant minor allele (G) was associated with higher D-dimer levels. The same variant has previously been associated with higher mean platelet volume (P = 9.0 × 10−18), wider mean platelet distribution width (P = 3.1 × 10−13), and lower platelet count (P = 6.1 × 10−9) (supplemental Table 7) and is located in multiple histone markers in liver tissue.44

Chr12.q24.31

A novel association was found for a common intronic variant rs2851436 in MPHOSPH9 (M-phase phosphoprotein 9; P = 3.9 × 10−8; OR, 0.94). This was the only transancestry genome-wide significant signal that did not reach genome-wide significance in the EA population alone (P = 2.1 × 10−7, supplemental Table 2). The association replicated (P = 1.0 × 10−6), and the minor allele of its proxy (rs1716157; r2 = 1.0, D′ = 1.0) was associated with higher plasma tissue plasminogen activator levels. rs2851436 was associated with smaller platelet mass (P = 2.4 × 10−10) and lower platelet count (P = 8.5 × 10−10), as reported for variants in LD (r2 = 0.9) with rs2851436; genetic variants in this region have previously been associated with hemoglobin levels.44,50 Colocalization analyses with eQTL data in blood and liver tissue revealed multiple candidate genes through which the GWAS signal could be mediated (supplemental Table 8). These include ABCB9, ARL6IP4, MPHOSPH9, and SBNO1, with the highest posterior probability (PP = 0.96) for MPHOSPH9 (supplemental Table 9).

Chr14.q23.1

A novel association was found for a common intragenic variant, rs11158204 (P = 1.5 × 10−8; OR, 0.94), which was 4 kb downstream from ARID4A (AT-rich interaction domain 4A). The association fell short of replication at the Bonferroni-correction level (P = 2.01 × 10−2; effect direction same) and it (or its proxy rs12433823; r2 = 0.98, D′ = 1.0) was associated with lower fibrinogen, lower plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1, and aPTT plasma levels. This region has been associated with red blood cell distribution width (P = 1.1 × 10−11) and our lead variant is in moderate LD (r2 = 0.5) with variants associated with coronary heart disease in a large GWAS meta-analysis.44,51 Colocalization analysis suggests that the observed VTE association may be mediated by variants that predict gene expression of ARID4A (PP = 0.72) and/or RP11-349A22 (PP = 0.69) in blood and/or liver.

Chr16.q23.3

A relatively common intronic variant in PLCG2, rs12445050, was associated with the risk of VTE (P = 6.7 × 10−13; OR, 1.11). The association replicated (P = 2.9 × 10−15) and was associated with aPTT. Similar to the GRK5 locus, the variant found to be associated with VTE has also been associated with larger mean platelet volume (P = 7.2 × 10−24).44 The gene product is a signaling enzyme, phospholipase Cγ2, and it has been shown to have a role in platelet activation biology.52

Chr17.p13.3

rs1048483 (P = 3.4 × 10−9; OR, 1.06) is intronic to SMG6 (nonsense-mediated messenger RNA decay factor) and is located in a conserved region and in enhancer histone mark H3K27ac in liver tissue. SMG6 codes for a housekeeping protein. The association replicated (P = 2.6 × 10−5) in MVP and was not associated with any of the 10 hemostasis phenotypes. Variants in and close to SMG6 have been associated with coronary heart disease (rs170041, r2 = 0.32), as well as with platelet mass and count (rs4455005; r2 = 0.59 between lead variants); rs1048483 was associated with lower platelet mass (P = 2.0 × 10−7) and smaller platelet count (P = 4.9 × 10−6) in UK Biobank data.44,51,53

Chr17.p13.1

rs12450494 is intragenic and 2.4 kb upstream from EIF5A (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A) and was only associated with VTE in EA-only meta-analysis (P = 2.5 × 10−8; OR, 1.06). The association did not replicate (P = .58) and was not associated with any of the 10 hemostasis phenotypes. Colocalization analyses provided evidence that the rs12450494 VTE signal is mediated through EIF5A expression in liver and blood (PP = 0.99 for blood and liver), as well as for GPS2 (G protein pathway suppressor 2) expression (PP = 0.99), a neighboring gene for which rs12450494 is situated downstream (supplemental Table 9).

Chr19.p13.2

rs7508633, an intronic variant in STX10, was associated with VTE risk (P = 2.0 × 10−9; OR, 0.94). The variant is located in a DNase I hypersensitive site and enhancer histone marks found in liver tissue and multiple blood-derived cells. The association did not replicate in MVP (P =.12; effect direction the same) and was not associated with the hemostasis traits. STX10 is a SNARE protein; another SNARE protein (STX2) and a SNARE binding protein (STXBP5) have been associated with plasma levels of VWF and with VTE.48,49

Novel VTE-associated variants at established loci

We identified genome-wide significant associations at the F5, C4BPA, FGG, F11, STXBP5, ZFPM2, ABO, TSPAN15, F2, VWF, SLC44A2, GP6, PROCR, and F8 loci (Table 1), all of which are genes known to be associated with VTE.4,5,7-9,49,54-62 For all loci with the exception of C4BPA, F11, and VWF, we identified only previously known signals at the established loci after conditional analyses. We did not find evidence for an association between the recently reported VWF variant rs35335161 with VTE (P = .88).63 At the C4BPA, F11, and VWF loci, we also identified new independent variants associated with VTE in conditional analyses. The genome-wide significant variant rs2842700 in C4BPA was in modest LD (r2 = 0.01; D′ = 1.0) with the previously reported rs3813948 variant in the C4BPA/C4BPB locus.56 The rs3813948 variant was not associated with VTE in our study (P = .38). No other independent variant at this locus was identified. For the F11 locus, we identified 3 genome-wide significant variants (rs2289252, rs2036914, and rs4253421); all remained significant after conditioning on the 2 previously reported variants at the F11 locus (rs2289252 and rs2036914).55,58,59 rs4253421 is intronic and was previously reported as being associated with F11, but not with VTE, phenotypes.27 rs4253421 is in strong LD with rs1593 (r2 = 0.84; D′ = 0.93), which has been associated with stroke.64 For the VWF locus, we observed a second genome-wide significant signal for rs216311 (P = 5.9 × 10−9) after conditioning on the strongest signal (rs1558519, P = 1.8 × 10−13), which is in LD with rs1063856 (r2 = 0.99; D′ = 1.0), a missense variant (Thr > Ala) previously associated with levels of VWF and FVIII, as well as with VTE.48,49 Rs216311 leads to a change in protein transcription (Thr > Ala) and represents a new VTE association within VWF. However, rs216311 was not associated with plasma VWF levels (P = .4) in a recently published GWAS, but it was associated with plasma levels of FVIII (P = .03), suggesting that it may influence the ability of the VWF molecule to carry FVIII.26

At the ABO, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, and PROCR loci, we found evidence of colocalization between GWAS and eQTL signals (supplemental Table 9). For ABO, the GWAS signal showed high posterior probability (PP = 0.93) of colocalizing with eQTL signals for ABO expression in liver. For the TSPAN15 region, we observed evidence of colocalization (PP = 0.88) with the eQTL signal for TSPAN15 expression in blood. We observed evidence of colocalization between the GWAS signal in the SLC44A2 region and eQTL signals for SLC44A2 expression (PP = 0.99) and ILF3-AS1 expression (PP = 0.98), all in blood. For the PROCR region, we observed the strongest posterior probability (PP = 0.93) of colocalization between the GWAS signal and eQTL for PROCR expression in blood. Evidence of colocalization of an eQTL and GWAS signal was not found for F5, FGG, F11, STXBP5, ZFPM2, F2, VWF, GP6, or F8 loci.

Previously identified variants not reaching genome-wide significance

We tested 9 variants in genes that have previously been reported to be associated with VTE (supplemental Table 10) but that did not reach genome-wide significance in our primary analyses: SERPINC1, KNG1, F13A1, HIVEP1, PAI-1, FGA, TCN2, F9, and THBD.65-73 The threshold for significance was set to 5.6 × 10−3 (0.05/9), and 3 variants reached the significance threshold: KNG1 rs1648711 (OR, 1.05 for minor allele; P = 4.5 × 10−4), TCN2 rs1884841 (OR, 1.05; P = 8.8 × 10−6), and F9 rs6048 (OR, 0.94 for minor allele; P = 7.8 × 10−8). A fourth variant (FGA rs6050) reached significance in the GWAS but was no longer significant (P = .49) in analyses conditioned on FGA rs2066864.

Previously known loci and variants

In addition to the novel associations, single variant and conditional meta-analysis provided evidence of association for known variants (Table 1; supplemental Results): F5 rs6025 and rs452454,55 ; FGG rs206686457 ; STXBP5 rs1039084 (strong LD with rs9390460)49 ; ZFPM2 rs4541868 (exact proxy for rs4541868)7,8 ; ABO variants rs8176749, rs687289, rs2519093, and rs5794595,60 ; TSPAN15 rs787077137 ; F2 variants rs191945075 (LD with rs1799963) and rs31365168 ; SLC44A2 rs4548995 (strong LD with rs2288904)7 ; NLRP2 rs1671135 (strong LD with GP6 rs1613662)4 ; PROCR variants rs867186 and rs608873561,62 ; and F8 rs143478537 (moderate LD with rs114209171).9

Heritability and genetic risk score

The heritability on the observed scale due to genotyped variants was 0.23 (standard error 0.02). Transforming this to the liability scale assuming a disease prevalence of 0.5% resulted in a heritability of 0.15 (standard error 0.01).

In total, the GRS included 37 variants (supplemental Table 11). Figure 2 shows the distribution of risk alleles for cases and controls. Relative to individuals with scores in the interquartile range (25% to 75% percentile), those in all other categories had VTE risks that were statistically different (Table 2). At the extremes, individuals at and below the bottom fifth percentile had a 50% lower risk for VTE (OR, 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43-0.61) and those at or above the top fifth percentile had a 3.2-fold greater risk for VTE (OR: 3.19; 95% CI: 2.89-3.52) relative to half of the population in the middle of the range.

Novel associations from transcriptome-wide association analyses of VTE

Transcriptome-wide association analyses identified 4 genes not previously associated with VTE: SPSB1, ERAP1, RP11-747H7.3, and RP4-737E23.2, and replicated SH2B3 (Table 3). SPSB1 genetic variation has previously been associated with eosinophil counts, as well as with neutrophil and eosinophil percentages of granulocytes.44 ERAP1 has been associated with Behcet’s syndrome, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory and autoimmune conditions that are purported risk factors for VTE.74-79 RP11-747H7.3 and RP4-737E23.2 are long noncoding RNAs. RP11-747H7.3 genetic variation has been associated with mean platelet volume.44 We replicated associations with SH2B3, previously hypothesized to be associated with VTE.80 SH2B3 plays a critical role in hematopoiesis, and SH2B3 has been associated with platelet density and count, lymphocyte count, reticulocyte count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, leukocyte count, erythrocyte count, granulocyte count, eosinophil and neutrophil counts, monocyte counts,44 coronary artery disease,51 stroke,81 and autoimmune diseases.82

MR of blood cell phenotypes and VTE

In our GWAS and TWAS findings, we observed that many of the novel loci associated with VTE have also been associated with blood cell traits. Therefore, we conducted MR analysis of VTE and 7 blood cell traits: lymphocyte counts, red blood cell volume and distribution width, and platelet volume, mass, distribution width, and count. We extracted the genome-wide significant variants associated with each of the blood cell traits from the report by Astle and colleagues, conducted using UK Biobank data.44 For VTE GWAS summary data, we excluded UK Biobank from our VTE meta-analysis to avoid sample overlap. We observed high heterogeneity in the inverse-variance–weighted MR analysis, which can imply pleiotropy; therefore, we performed MR Egger as a sensitivity analysis. Across the MR approaches, there was some evidence that blood traits, particularly red blood cell and platelet distribution widths, were causally associated with VTE risk (supplemental Table 12). Although MR Egger regression can provide unbiased estimates in the presence of directional pleiotropy, it relies on the InSIDE assumption, that the instrument strength is independent of the direct effect. Therefore, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis using the weighted-median MR, which is not as sensitive as MR Egger regression to violation of the InSIDE assumption but requires that at least 50% of the genetic variants are valid instrumental variables.42 In contrast to the MR Egger regression, we observed no evidence that platelet mass and count are associated with VTE; however, we observed suggested associations for platelet and red cell distribution width (both P < .05). We note that the estimates for platelet and red blood cell distribution width were consistent across MR methods, adding support for the association. Although platelet distribution width was associated with an increased risk for VTE, red blood cell distribution width was associated with a decreased risk, an unexpected result given previous observations studies.83-85 However, given the inconsistent results from the range of MR approaches that we applied, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

In transancestry GWAS meta-analysis data from 18 studies, combined with TWASs and colocalization analyses, we identified 16 loci newly associated or confirmatory with the VTE phenotype: 11 from GWAS meta-analyses and 5 from TWAS analyses. Among the 11 novel GWAS findings, 6 replicated in an independent data set; 3 of 11 had strong evidence of colocalized GWAS genetic and transcription signals associated with the VTE phenotype. The 37-variant GRS identified risk across the range of scores. MR investigations suggested that blood traits may contribute to the underlying biology of VTE risk.

Biologic insights

A theme from the discovery was that many newly associated loci were also associated with blood traits, particularly platelets. GP6,4 ZFPM2,86 VWF, and ABO loci have been associated with platelet biology and with VTE risk. Discovery findings produced a list of new candidates, including PLEK, GRK5, MPHOSPH9, PLCG2, SMG6, and SH2B3. Further, PLEK, MPHOSPH9, and ARID4A were associated with red blood cell traits. MR analyses suggested that platelet and red blood cell traits have an etiologic role in VTE; however, the inconsistency in MR results across various statistical approaches indicates that the relationship between blood traits and VTE is likely complex and that more research is needed to clarify the role of individual blood cell traits. Although the role of coagulation in VTE is very well characterized, the roles of platelets and red blood cells in thrombosis are less well characterized, and research continues to provide new insights into biologic mechanisms.87,88

Most of the 11 newly identified signals were intragenic, and the highest-signal variants were intronic. For 3 of the loci (12.q24.31 [MPHOSPH9], 14.q23.1 [ARID4A], and 17.p13.1 [EIF5A]), we found evidence that the identified variants were influencing VTE risk through gene expression in blood and liver tissue. The role of gene-specific expression in VTE risk was further supported by our agnostic TWAS analysis identifying 4 novel candidate genes whose imputed gene expression was associated with VTE risk. In addition, several of the lead variants in the newly identified loci were located in regulatory regions, as identified in blood and liver tissue.

Clinical significance

Although genetic predictors of VTE have been known since the 1960s, consensus on the clinical and economic utility of assessing genetic risks has not been reached.89 In this article, we expand the number of independent variants associated with VTE from 23 to 37, 32 of which have strong replication evidence. We found limited statistical evidence that the 11 novel VTE variants were associated with plasma levels of the 10 hemostasis traits, suggesting that the majority of these variants affect VTE risk through other mechanisms or pathways yet to be characterized. A GRS constructed from these variants identified a risk gradient of risk alleles that could be tested for utility in the setting of shortening (those in the lowest fifth percentile of the GRS distribution were at a 50% decreased risk for VTE relative to those with mid-range GRSs) or prolonging (those in the highest fifth percentile of the GRS distribution were at threefold increased risk for VTE relative to those with mid-range GRSs) prophylaxis for incident VTE events. A better understanding of the biologic pathways through which individual or aggregated (GRS) variants contribute to risk is needed, but evidence from this study suggest that little of any additional risk or protection from the novel VTE variants contributing to the GRS are mediated by the 10 hemostasis traits interrogated. Given the roles of anticoagulation therapy and, to some extent, antiplatelet therapy in reducing the risk for incident and recurrent VTE, findings from this GWAS meta-analysis, especially those involved in platelet biology, may eventually be used to identify those who are at highest risk for an event, incident or otherwise, and provide guidance for the most effective treatment strategy.90,91

Strengths and limitations

The present study constitutes the largest GWAS of VTE to date and the first transancestry GWAS meta-analysis of VTE. The meta-analysis approach performs equally well in terms of efficiency compared with a combined (mega) analysis approach.92 Although we had good statistical power for common variants with modest effect sizes, uncommon and familial rare variants (eg, those in PROS1 and PROC), even those with large effect sizes, are not likely to be detected by GWAS, especially if the variants are poorly imputed. However, we were able to detect a variant with an MAF of 0.01 and effect size ≥ 30% with 82% power. We assessed the association of previously reported VTE variants in our GWAS (supplemental Table 10) and found that some previously reported variants were not associated with VTE (P > .1) in our data. We had modest numbers of AA participants, which limited our power to identify associations unique to them and to test differences across ancestry. Other investigators have attempted to identify variants unique to the AA population.93 Further, P values were generally higher in EA-only meta-analyses than in combined EA and AA analyses, suggesting that differential LD with any causative variant may have diluted some genetic signals in the transancestry analyses. Although all 11 newly associated loci exhibit genome-wide significant signals, replication in an independent study was only successful for 6; the remaining 5 were not replicated because of the low statistical power given MAF and effect size (range of power from 48% to 72% for α 0.0045) or as a result of a false-positive GWAS signal. Adjusting for winner’s curse of the original point estimate would further diminish power. For conditional analyses, we relied on a genotype-imputed data set of >9000 individuals from 4 cohorts, and it is possible that we might have missed additional independent signals as a result of mismatching LD patterns or incomplete coverage of the genetic variation in the reference population. However, variants in strong LD with one another can each be causally related to the outcome. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to apply TWASs to VTE. Using transcription information to inform discovery is particularly powerful when many variants in a region contribute to disease risk, but no single variant has an association strong enough to reach genome-wide significance by itself. The TWAS approach aims to detect situations in which gene expression and phenotype are associated, which may not reflect the complete underlying biology. For example, in the case in which the variant leads to a change in the protein structure, such as F5 rs6025, the variant is not expected to be linked to expression. For 2 of the TWAS signals (ERAP1 and SH2B3), we did not observe strong evidence for a colocalization between the eQTL and GWAS signal. Both of these regions only showed moderate single-variant associations with VTE (lowest single-variant P values were P = 7.8 × 10−6 for ERAP1 and P = 2.9 × 10−6 for SH2B3). Thus, these results likely reflect a situation in which there are strong eQTL signals with multiple variants/loci associated with gene expression, each with a small effect on VTE.

Conclusions

We identified 34 independent genetic signals for VTE risk from GWAS meta-analysis, of which 14 are newly reported associations. This included 11 newly associated genetic loci and 3 new independent signals in known genes. Further, TWAS identified 5 additional genetic loci. In some of the loci, we found that the association signal for novel and previously known regions is likely mediated by gene expression of nearby genes. We further show that a GRS based on 37 VTE-susceptibility variants can identify a subset in the population that is at particularly high risk for developing VTE. The MR analyses suggested that blood traits may contribute to the underlying biology of VTE risk.

Please contact Nicholas L. Smith (nlsmith@u.washington.edu) or David-Alexandre Trégouët (david-alexandre.tregouet@u-bordeaux.fr) for information on INVENT Consortium data sharing.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The INVENT Consortium thanks all of the participants across the 18 studies who provided their health information to support these analyses.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL134894, HL139553, and HL141791 (N.L.S.). The K.G. Jebsen Thombosis Research and Expertise Center is supported by an independent grant from Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen (J.H.) and HL116854 (C. Kabrhel). Sources of funding for the specific cohorts can be found in the supplemental Materials.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Authorship

Contribution: S.L., E.N.S., A.v.H.V., M.d.A., D.I.C., P.S., N.P., M.K.P., S.R.H., S.M.D., P.N., D.K., P.S.d.V., M.S.-L., J.E.H., K.A.F., J.S.P., A.P.R., M.E.G., C.J.O., J.-B.H., F.R.R., J.A.H., B.M.P., W.T., C. Kabrhel, K.H., P.M.R., P.-E.M., A.D.J., C. Kooperberg, D.-A.T., and N.L.S. designed the study; S.L., L.W., W.G., J.A.B., J.W.P., J.H., B.M.B., M.-H.C., C.T., M.G., K.L.W., J.M., S.K.B., S.M.A., S.M.D., P.N., D.K., P.S.d.V., M.S.-L., J.E.H., T.K.B., B.M.M., K.T., J.-F.D., B.M., P.K., D.-A.T., and N.L.S. designed and/or performed analyses; S.L., P.-E.M., A.D.J., C. Kabrhel, D.-A.T., and N.L.S. wrote 1 or more parts of the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and provided comments on the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: B.M.P. serves on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access project funded by Johnson & Johnson. P.N. has received grant support from Amgen, Apple, and Boston Scientific and is a scientific advisor to Apple. S.M.D. receives institutional funding from CytoVas LLC and RenalytixAI. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

D.K., Emma Busenkell, Renae Judy, Julie Lynch, Michael Levin, J.H., Krishna Aragam, Mark Chaffin, Mary Haas, S.L., Themistocles L. Assimes, Jie Huang, Kyung Min Lee, Qing Shao, J.E.H., C. Kabrhel, Yunfeng Huang, Yan V. Sun, Marijana Vujkovic, Danish Saleheen, Donald R. Miller, Peter Reaven, Scott DuVall, William Boden, Saiju Pyarajan, A.P.R., D.-A.T., Peter Henke, C. Kooperberg, J. Michael Gaziano, John Concato, Daniel J. Rader, Kelly Cho, Kyong-Mi Chang, Peter W. F. Wilson, N.L.S., C.J.O., Philip S. Tsao, Sekar Kathiresan, Andrea Obi, S.M.D., and P.N. represent the Million Veteran Program. The INVENT Consortium consists of all the authors of the present paper.

Correspondence: Nicholas L. Smith, Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, 1730 Minor Ave, Suite 1360, Seattle WA 98101; e-mail: nlsmith@u.washington.edu.