Background: The survival benefit of ruxolitinib, approved for treatment of intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera (PV) MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia (ET) MF, has been reported in phase-3 studies. However, population-based comparison data of its efficacy in primary and secondary MF are limited. We analyzed the effects of ruxolitinib in MF patients from a real-world population using National Health Insurance Research Database of Korea.

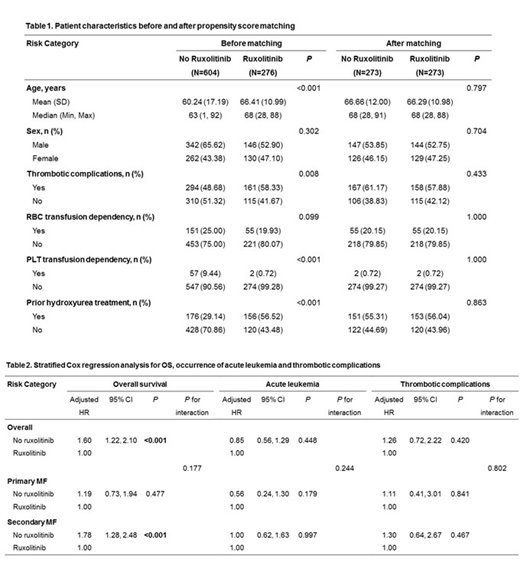

Methods: A total of 1171 patients who diagnosed MF (ICD-10 code D47.4) from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2017 were identified. Of these, 291 patients previously diagnosed with leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, or lymphoma were excluded. The remaining 880 patients (361 patients with primary MF and 519 with secondary MF) were included in the study and divided into 2 group according to ruxolitinib treatment. Patients who received ruxolitinib (n = 276) were matched with those who did not receive ruxolitinib (n = 604) using the 1:1 greedy matching algorithm. Propensity scores were formulated using six variables: age, sex, previous history of arterial/venous thrombosis, red blood cell (RBC) or platelet (PLT) transfusion dependence, and previous hydroxyurea treatment. Overall survival (OS) and occurrence of acute leukemia and thrombotic complications were evaluated using stratified Cox-regression analysis between patients who received ruxolitinib and those who did not. Among the former, we evaluated the risk factors for OS as the primary outcome and occurrence of acute leukemia, thrombotic complications, and RBC and PLT transfusion response as secondary outcomes using multivariable Cox-regression analysis. Primary MF was defined as MF without a prior diagnosis of PV (ICD-10 code D45), ET (ICD-10 code D47.3), and chronic myeloproliferative disease (ICD-10 code D47.1). Secondary MF was defined as MF, which was not included in primary MF.

Results: In the Cox-regression analysis for OS, non-ruxolitinib treatment (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22-2.10; P <0.001) was a significant prognostic factor for shorter survival. In the subgroup analysis, non-ruxolitinib treatment was a significant prognostic factor for poor survival in patients with secondary MF (adjusted HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.28-2.48; P <0.001). Contrastingly, no significant difference was observed in patients with primary MF (adjusted HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.94; P = 0.478). Ruxolitinib treatment did not affect the occurrence of leukemia and thrombotic complications in patients with both primary and secondary MF. In the multivariable Cox-regression analysis for OS in patients treated with ruxolitinib, older age (adjusted HR, 1.06; P <0.001), RBC (adjusted HR, 2.91; P <0.001), and PLT (adjusted HR, 9.65; P <0.001) transfusion dependence were significantly associated with poor survival, although MF type did not significantly affect survival. In the multivariable analysis for secondary outcomes, PLT transfusion dependency was the only significant risk factor for the occurrence of acute leukemia (adjusted HR, 4.78; P = 0.046) and thrombotic complications (adjusted HR, 14.16; P = 0.002). Older age (adjusted HR, 1.05; P <0.001) and previous hydroxyurea treatment (adjusted HR, 0.41; P = 0.005) significantly affected the response to RBC transfusion. Patients with secondary MF who received ruxolitinib showed a better RBC transfusion response than those with primary MF (adjusted HR, 0.51; P = 0.055).

Conclusions: Ruxolitinib treatment led to better survival in patients with MF and might be more beneficial in secondary MF. Moreover, ruxolitinib was more efficacious in reducing RBC transfusion requirement in secondary MF than in primary MF. Further studies on the efficacy of ruxolitinib in other populations are needed.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.