Key Points

Plasmodium falciparum sexual parasites can fully develop within human erythroblasts.

Gametocytes and parasite-derived extracellular vesicles delay erythropoiesis to allow complete gametocyte development in nucleated cells.

Abstract

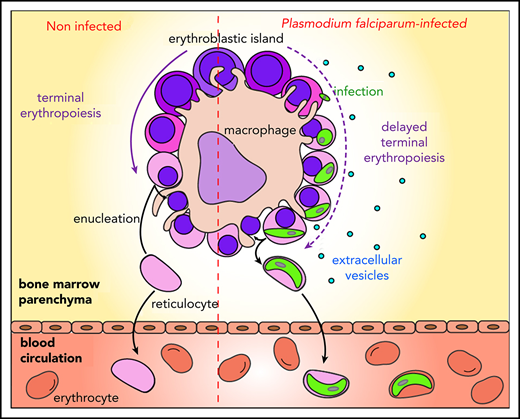

Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes, the sexual stage responsible for malaria parasite transmission from humans to mosquitoes, are key targets for malaria elimination. Immature gametocytes develop in the human bone marrow parenchyma, where they accumulate around erythroblastic islands. Notably though, the interactions between gametocytes and this hematopoietic niche have not been investigated. Here, we identify late erythroblasts as a new host cell for P falciparum sexual stages and show that gametocytes can fully develop inside these nucleated cells in vitro and in vivo, leading to infectious mature gametocytes within reticulocytes. Strikingly, we found that infection of erythroblasts by gametocytes and parasite-derived extracellular vesicles delay erythroid differentiation, thereby allowing gametocyte maturation to coincide with the release of their host cell from the bone marrow. Taken together, our findings highlight new mechanisms that are pivotal for the maintenance of immature gametocytes in the bone marrow and provide further insights on how Plasmodium parasites interfere with erythropoiesis and contribute to anemia in malaria patients.

Introduction

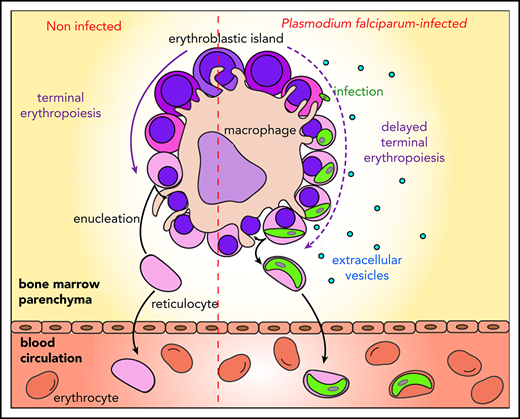

Malaria remains a major public health threat, with half a million deaths annually.1Plasmodium falciparum is the human parasite causing the most severe form of the disease. Sexual parasites, called gametocytes, are the only stage responsible for transmission from humans to Anopheles mosquitoes that spread the parasite in populations. Thus, understanding the biology of gametocyte development is crucial for successful malaria elimination. P falciparum gametocytes development takes ∼10 days, and their maturation is divided into 5 stages.2,3 Only mature stage V gametocytes circulate in the bloodstream where they are available for uptake by mosquitoes. In contrast, immature gametocytes from stages I to IV are sequestered in deep tissues, presumably to avoid clearance by the spleen. Recent examination of autopsies and ex vivo samples from malaria-infected patients revealed that immature gametocytes are enriched in the bone marrow.4-6 The emerging role of the erythropoietic environment in hosting gametocytes suggests the presence of mechanisms that regulate homing and maintenance of sexual parasites in this niche. Unlike asexual parasites that sequester by cytoadhesion of infected erythrocytes through PfEMP1 interaction with endothelial receptors, gametocytes do not express PfEMP1 and immature gametocyte-infected erythrocytes (GIEs) do not significantly adhere to endothelial cells from different organs, including bone marrow endothelial cells.7,8 These features are consistent with the observation that gametocytes preferentially accumulate in the bone marrow extravascular space.6 Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the mechanism of gametocyte sequestration in the bone marrow parenchyma. For instance, immature GIE maintenance in this microenvironment may be dependent on adhesion to nonendothelial bone marrow cells, because erythrocytes infected by asexual and immature gametocytes adhere to bone marrow mesenchymal cells via trypsin-sensitive parasite ligands exposed on the erythrocyte surface.9,10 Moreover, the increased rigidity of immature GIEs may also contribute to their sequestration locally by mechanical retention.11 Although both assumptions have yet to be validated in vivo, they do not fully reconcile with histological analyses of the bone marrow parenchyma reporting that gametocytes are predominantly localized in close proximity to erythroblastic islands.6 These specialized niches, where the terminal erythroid differentiation occurs, consist of a macrophage surrounded by differentiating erythroblasts.12 So far, the nature of the interactions between gametocytes and these islands remains elusive. Because immature GIEs fail to adhere to primary human erythroblasts,13 the contiguity observed between immature gametocytes and erythroblastic islands may be the result of erythroblast infection by parasites, followed by the maturation of gametocytes within these nucleated cells. Such a mechanism would allow gametocytes to benefit from direct adhesion of erythroblasts to the nursing macrophages in erythroblastic islands. In support of this hypothesis, studies have demonstrated that nucleated erythroid cells support P falciparum invasion.14-17 Moreover, the development of P falciparum asexual parasites can take place in ex vivo culture of primary human erythroblasts, and immature gametocytes of stages I and II have been observed in nucleated cells in vitro.6,18 These interactions may contribute to the maintenance of immature gametocytes from stage I to IV in the bone marrow parenchyma until the release of mature gametocyte-containing reticulocytes in the circulation. The consequences of these infections on human erythropoiesis are unknown, but they may be linked to erythroid disorders observed in malaria patients.19

Here, we set up a protocol to produce and quantify P falciparum gametocytes in a synchronized culture of primary human erythroblasts. We combined this approach with in vivo analyses to investigate, for the first time, P falciparum sexual maturation processes in erythroid precursors, as well as their effects on erythropoiesis.

Methods

Parasite culture and transfection

The P falciparum NF54 clone B1020 and the VarO line21 were cultivated in vitro as described.22 The NF54-pfs47-Hsp70-GFP line (called Hsp70-GFP), expressing GFP under the control of the constitutive promoter hsp70, and the NF54-pfs47-Pfs16-GFP line (called Pfs16-GFP), expressing GFP under the control of the gametocyte-specific promoter Pfs16, were obtained by transfection into clone B10, as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Malaria patient bone marrow

Three bone marrow smears were obtained from a 20-year-old female patient admitted to Ispat General Hospital with P falciparum infection (positive by microscopy and rapid diagnostic test), anemia (hemoglobin, 5.2 g/dL), and pancytopenia. The patient’s admission parasitemia (second day of fever) was 1320 parasites per microliter before antimalarial treatment was initiated, and no sexual forms of the parasite were detected on thick or thin blood smears. Bone marrow biopsy was carried out as part of the standard clinical care of malaria-related anemia, and secondary analyses of the tissue were performed through an ongoing study approved by the Institutional Review Boards of New York University School of Medicine (i12-03016), Ispat General Hospital (3137/E/05), and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Smears were immediately fixed by immersion in −20°C methanol for 5 minutes and left to dry prior to the immunofluorescence analyses.

Human primary erythroblasts

The human primary erythroblasts culture method is described in detail in supplemental Methods. CD34+ progenitor cells were collected from bone marrow aspirate or from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor–mobilized peripheral blood after cytapheresis from human healthy donors who gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The study has been approved by the INSERM Institutional Review Board IRB 00003888. Erythroid differentiation was analyzed by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of cytospun samples and by flow cytometry. Reticulocytes production was monitored using the DNA-labeling DRAQ5 probe (1/5000; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Erythroblast infection

At 40 hours postinfection (hpi), tightly synchronized schizonts were purified by magnetic isolation and were added to human primary erythroblasts at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2. Infected cells were cultivated at 37°C, 5% CO2, 5% O2 in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium containing 15% BIT 9500, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, erythropoietin (4 U/mL), hypoxanthine (10 mM), and heat-inactivated human serum (10%). At 24 hpi, noninfected erythrocytes were removed by adding erythrocyte lysis buffer (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Infected erythroblast cultures were diluted daily to 0.8 millions cells per milliliter. Gametocytemia and total parasitemia were monitored by flow cytometry analysis of the Pfs16-GFP and the Hsp70-GFP lines, respectively, using a BD Accuri C6 cytometer. DNA was labeled with the DRAQ5 probe (1/5000), and DNA levels were used to discriminate erythroblasts and Plasmodium-infected reticulocytes.

Electron microscopy

Erythroblasts infected at 6 days postinfection (dpi) were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, and 1 mM calcium chloride in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 10 minutes and processed for transmission electron microscopy, as described in supplemental Methods. Samples were observed using a Hitachi Transmission Electron Microscope HT7700. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) were incubated on Formvar-coated grids for 2 minutes and then with uranyl acetate 1% for 2 minutes. EVs were observed directly with a JEOL 1011 transmission electron microscope. Acquisitions were performed with a Gatan Orius 1000 camera.

Fluorescent microscopy

Infected erythroblasts were fixed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline/4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33342 (1/20 000) and PKH26. For immunofluorescence, cells or bone marrow smears were stained with anti–Glycophorin A (GPA) and anti–Pf11-123 antibodies. Details are provided in supplemental Methods. All samples were observed (original magnification ×100) using a Leica DMi8 microscope.

Gamete egress assay

At 9 to 10 dpi within erythroblasts or erythrocytes, Pfs16-GFP gametocytes were stained for 15 minutes at 37°C with 5 µg/mL wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)–Alexa Fluor 647, pelleted, and then mixed in 5 µL of human serum supplemented with 100 µM xanthurenic acid at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples were observed at ×100 magnification using a Leica DMi8 microscope. One hundred cells were counted for each condition.

Purification of EVs

The protocol for EV purification was adapted from Mbagwu et al.24 Purified EVs and conditioned medium were labeled with PC7-conjugated anti-GPA (1/10) or with the isotypes-PC7–conjugated monoclonal antibody (1/10; both from Beckman Coulter) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Total EVs were determined and counted by flow cytometry and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Details are provided in supplemental Methods.

Determination of the oxidative stress

Two days after incubation with EVs, medium conditioned with Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes (iECM), or iECM depleted of EVs (iECM − EV), erythroblasts were incubated with dihydroethidium (DHE) (2 mM; Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. The percentage of oxidized cells was determined by flow cytometry using a BD Accuri C6 cytometer.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test, paired Student t test, or 1-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism 7.

Results

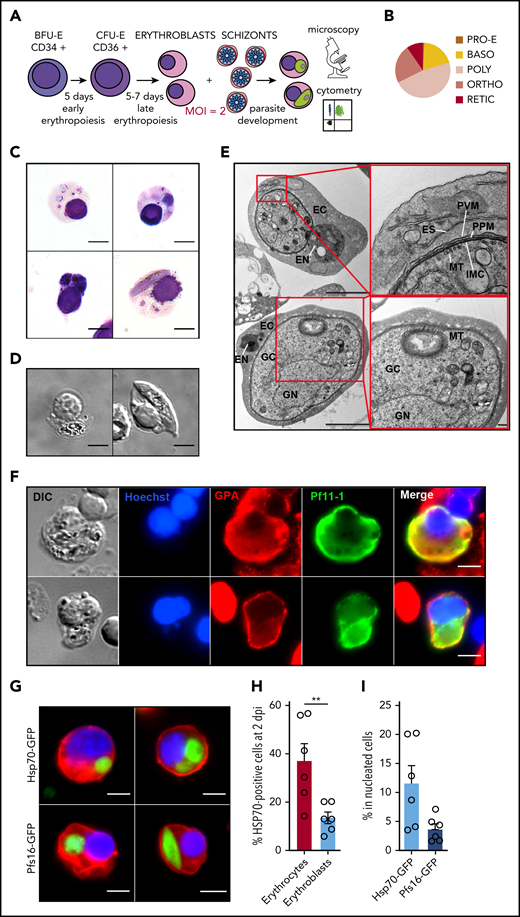

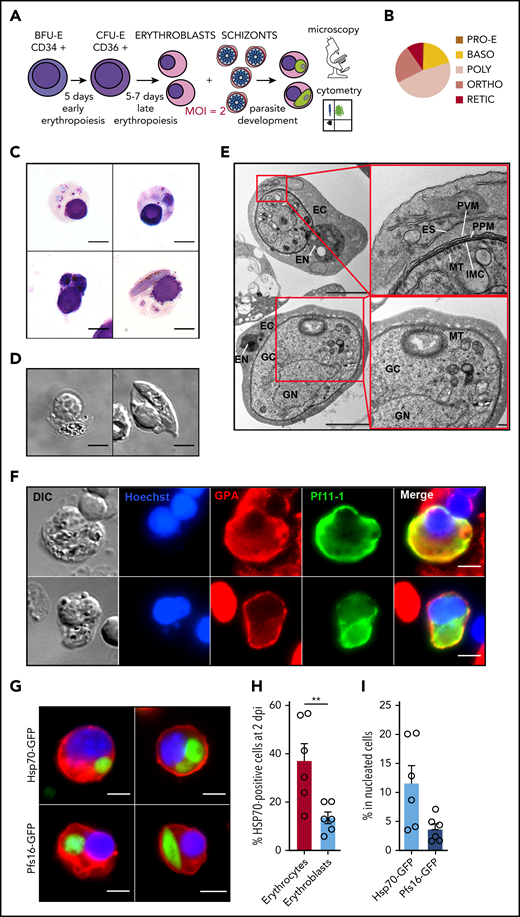

Immature gametocytes develop properly within human primary erythroblasts

To address whether P falciparum gametocytes can develop within erythroid precursors, we set up an infection protocol in which purified synchronized schizonts were added to human primary erythroblasts derived from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor–mobilized peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirate (Figure 1A). At the time of infection, erythroblasts were primarily at the polychromatic stage (Figure 1B). As previously reported,6,18 we observed young asexual parasites within erythroblasts at 24 hpi (Figure 1C). We then observed trophozoites and schizonts at 2 dpi and immature gametocytes at 6 dpi (Figure 1C-D). Immature gametocytes developing within erythroblasts presented typical features of sexual parasites, such as a microtubular network and an inner membrane complex25,26 (Figure 1E). Moreover, the gametocyte-specific protein Pf11-1 (PF3D7_1038400.1) was detected in the parasite and in the infected erythroblast27,28 (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 1).

Immature gametocytes develop properly within human primary erythroblasts. (A) Diagram illustrating the erythroblast infection protocol. Burst forming unit-erythroid cells (BFU-E) expressing CD34 were cultivated for 7 days to generate colony forming unit-erythroid cells (CFU-E) expressing CD36 and then CFU-E were allowed to differentiate into late erythroblasts for 5 to 7 days. Synchronized GFP-expressing schizonts at 40 hpi were added to erythroblasts at an MOI of 2. After several days of culture, infected erythroblasts were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry. (B) Distribution of the different erythroblast stages at the time of infection. Morphological analysis of erythroblasts was performed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining of cytospin from 3 independent experiments. (C) Erythroblast infection was observed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining at 1 dpi (ring stage, upper left panel), 2 dpi (trophozoite stage, upper right panel and schizont stage, lower left panel), and 6 dpi (stage III gametocyte, lower right panel). Scale bars, 5 μm. (D) Gametocytes within erythroblasts at 6 dpi were observed by differential interference contrast microscopy: stage III gametocyte (left panel) and stage IV gametocyte (right panel). Scale bars, 5 μm. (E) Transmission electron microscopy shows that immature gametocytes within infected erythroblasts present typical sexual structures as the microtubular network (MT) and the inner membrane complex (IMC). Scale bars, 1 µm (left panels); 200 nm (right panels). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of paraformaldehyde-fixed gametocyte-infected erythroblast at 6 dpi stained with anti–Pf11-1 antibodies (green) and with anti-GPA labeling the erythroblast membrane (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (G) Infection with the Hsp70-GFP line (upper panels) and with the Pfs16-GFP line (lower panels) was observed by fluorescent microscopy at 2 dpi (upper panels and lower left panel) and at 6 dpi (lower right panel). Erythroblast membrane is stained with PKH-26 (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (H) Infection of erythrocytes or erythroblasts with the Hsp70-GFP line was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi. (I) Infection of erythroblasts with the Hsp70-GFP and Pfs16-GFP lines was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi. (H-I) Circles indicate the number of independent experiments (n = 6) that were performed on erythroblasts derived from cytaphereses (n = 5) or bone marrow aspirates (n = 1) from 4 independent donors. Error bars show the standard error of the mean. **P < .01. BASO, basophilic stage; DIC, differential interference contrast; EC, erythroblast cytosol; EN, erythroblast nucleus; ES, exomembrane system; GC, gametocyte cytosol; GN, gametocyte nucleus; ORTHO, orthochromatic stage; POLY, polychromatic stage; PPM, parasite plasma membrane; PRO-E, proerythroblast stage; PVM: parasitophorous vacuole membrane; RETIC, reticulocyte stage.

Immature gametocytes develop properly within human primary erythroblasts. (A) Diagram illustrating the erythroblast infection protocol. Burst forming unit-erythroid cells (BFU-E) expressing CD34 were cultivated for 7 days to generate colony forming unit-erythroid cells (CFU-E) expressing CD36 and then CFU-E were allowed to differentiate into late erythroblasts for 5 to 7 days. Synchronized GFP-expressing schizonts at 40 hpi were added to erythroblasts at an MOI of 2. After several days of culture, infected erythroblasts were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry. (B) Distribution of the different erythroblast stages at the time of infection. Morphological analysis of erythroblasts was performed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining of cytospin from 3 independent experiments. (C) Erythroblast infection was observed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining at 1 dpi (ring stage, upper left panel), 2 dpi (trophozoite stage, upper right panel and schizont stage, lower left panel), and 6 dpi (stage III gametocyte, lower right panel). Scale bars, 5 μm. (D) Gametocytes within erythroblasts at 6 dpi were observed by differential interference contrast microscopy: stage III gametocyte (left panel) and stage IV gametocyte (right panel). Scale bars, 5 μm. (E) Transmission electron microscopy shows that immature gametocytes within infected erythroblasts present typical sexual structures as the microtubular network (MT) and the inner membrane complex (IMC). Scale bars, 1 µm (left panels); 200 nm (right panels). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of paraformaldehyde-fixed gametocyte-infected erythroblast at 6 dpi stained with anti–Pf11-1 antibodies (green) and with anti-GPA labeling the erythroblast membrane (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (G) Infection with the Hsp70-GFP line (upper panels) and with the Pfs16-GFP line (lower panels) was observed by fluorescent microscopy at 2 dpi (upper panels and lower left panel) and at 6 dpi (lower right panel). Erythroblast membrane is stained with PKH-26 (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (H) Infection of erythrocytes or erythroblasts with the Hsp70-GFP line was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi. (I) Infection of erythroblasts with the Hsp70-GFP and Pfs16-GFP lines was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi. (H-I) Circles indicate the number of independent experiments (n = 6) that were performed on erythroblasts derived from cytaphereses (n = 5) or bone marrow aspirates (n = 1) from 4 independent donors. Error bars show the standard error of the mean. **P < .01. BASO, basophilic stage; DIC, differential interference contrast; EC, erythroblast cytosol; EN, erythroblast nucleus; ES, exomembrane system; GC, gametocyte cytosol; GN, gametocyte nucleus; ORTHO, orthochromatic stage; POLY, polychromatic stage; PPM, parasite plasma membrane; PRO-E, proerythroblast stage; PVM: parasitophorous vacuole membrane; RETIC, reticulocyte stage.

To evaluate infection efficiency by flow cytometry, human primary erythroblasts were infected with 2 transgenic lines expressing fluorescent reporters: the Hsp70-GFP line (supplemental Figure 2), expressing GFP throughout the entire parasite life cycle under the control of the constitutive promoter hsp70, to monitor total parasitemia and the Pfs16-GFP line (supplemental Figure 3), expressing GFP under the control of the gametocyte-specific promoter Pfs16, to monitor gametocytemia (Figure 1G). The infection yield was lower in erythroblasts than in erythrocytes under the same conditions of infection; however, total parasitemia in nucleated cells at 2 dpi was 11.6%, indicating that the infection protocol is efficient (Figure 1H). Moreover, the gametocytemia in nucleated cells at 2 dpi was 3.7% (Figure 1I). These results suggest that immature gametocytes are adapted to develop in nucleated primary erythroblasts.

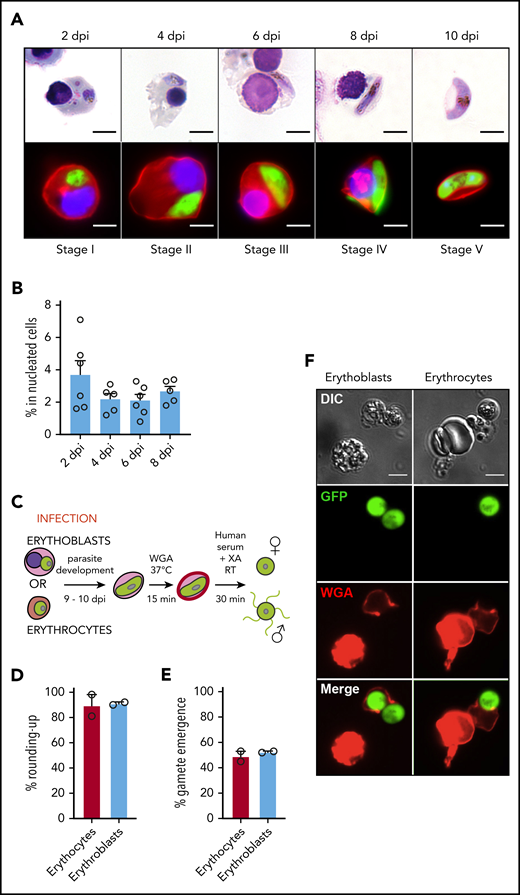

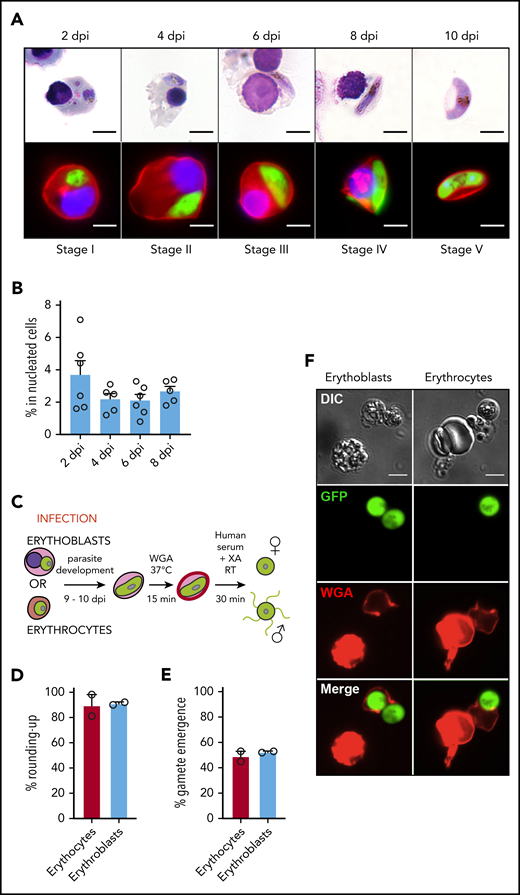

Infection of erythroblasts allows complete gametocytogenesis

To determine whether gametocytes undergo full maturation within erythroid precursors, erythroblast infection was followed for 10 days. We observed that nucleated cells supported immature gametocyte development from stage I to IV for 8 days, leading to the production of mature gametocytes within reticulocytes at 10 dpi (Figure 2A). The gametocytemia in nucleated cells decreased about twofold between 2 dpi and 4 dpi and then remained stable for several days (Figure 2B), indicating that sexual parasites can persist for several days in erythroblast culture. Because the ability of mature gametocytes to undergo gametogenesis is a marker of functionality, we quantified round and egressed gametes upon a temperature drop and an increase in serum concentration supplemented with xanthurenic acid (Figure 2C). Mature gametocytes were able to undergo a release of round or motile flagellated gametes from their host cell with a similar efficiency in reticulocytes and in erythrocytes (Figure 2D-F; supplemental Figure 4). These results indicate that gametocytes could achieve their maturation from stage I to IV in nucleated cells and suggest that resulting mature gametocytes within reticulocytes are potentially functional and may be transmissible to mosquitoes.

Infection of erythroblasts allows complete gametocytogenesis. (A) Gametocyte maturation after erythroblast infection with the Pfs16-GFP line was observed by light microscopy after May-Grünwald Giemsa staining (upper panels) and by fluorescent microscopy (lower panels). Erythroblast membrane was stained with PKH-26 (red). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Infection of erythroblasts with the Pfs16-GFP line was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2, 4, 6, and 8 dpi. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments (n = 6) that were performed on erythroblasts derived from cytaphereses (n = 5) or bone marrow aspirates (n = 1) from 4 independent donors. (C) Diagram illustrating the gamete activation protocol. After infection of erythroblasts or erythrocytes with Pfs16-GFP schizonts, gametocytes were allowed to differentiate for 9 to 10 days within erythroid precursors or erythrocytes. Mature gametocytes were stained with WGA–Alexa Fluor 647 (red) for 15 minutes at 37°C and then activated in human serum and xanthurenic acid (XA) at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes, leading to gamete activation. (D) GFP+ cells were scored as round or crescent shaped and plotted as percentage rounded-up. (E) GFP+ cells were scored as positive or negative for WGA-Alexa Fluor 647 staining and plotted as percentage gamete emergence. (D-E) One hundred cells were scored per condition. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. (F) Fluorescence microscopy of activated gametes from a culture of infected erythroblasts (left panels) or infected erythrocytes (right panels) with the Pfs16-GFP line. Erythroid cell membrane is stained with WGA–Alexa Fluor 647 (red). Scale bars, 5 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast.

Infection of erythroblasts allows complete gametocytogenesis. (A) Gametocyte maturation after erythroblast infection with the Pfs16-GFP line was observed by light microscopy after May-Grünwald Giemsa staining (upper panels) and by fluorescent microscopy (lower panels). Erythroblast membrane was stained with PKH-26 (red). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Infection of erythroblasts with the Pfs16-GFP line was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2, 4, 6, and 8 dpi. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments (n = 6) that were performed on erythroblasts derived from cytaphereses (n = 5) or bone marrow aspirates (n = 1) from 4 independent donors. (C) Diagram illustrating the gamete activation protocol. After infection of erythroblasts or erythrocytes with Pfs16-GFP schizonts, gametocytes were allowed to differentiate for 9 to 10 days within erythroid precursors or erythrocytes. Mature gametocytes were stained with WGA–Alexa Fluor 647 (red) for 15 minutes at 37°C and then activated in human serum and xanthurenic acid (XA) at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes, leading to gamete activation. (D) GFP+ cells were scored as round or crescent shaped and plotted as percentage rounded-up. (E) GFP+ cells were scored as positive or negative for WGA-Alexa Fluor 647 staining and plotted as percentage gamete emergence. (D-E) One hundred cells were scored per condition. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. (F) Fluorescence microscopy of activated gametes from a culture of infected erythroblasts (left panels) or infected erythrocytes (right panels) with the Pfs16-GFP line. Erythroid cell membrane is stained with WGA–Alexa Fluor 647 (red). Scale bars, 5 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast.

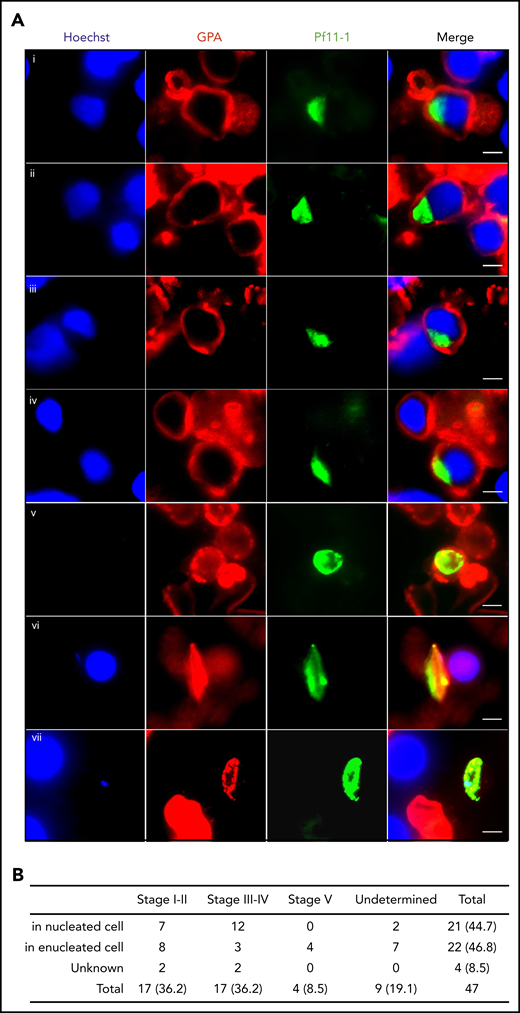

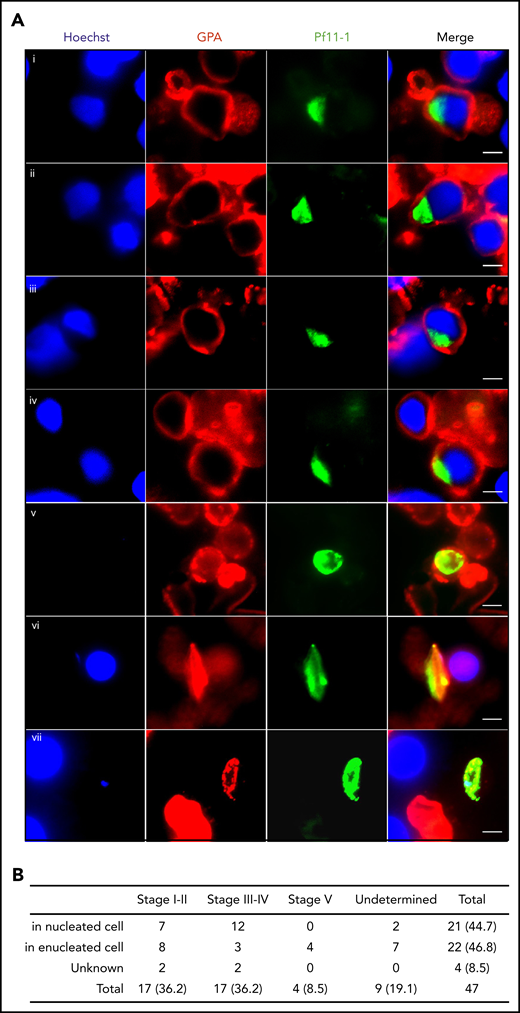

To address whether these in vitro observations can be translated in vivo, we analyzed 3 bone marrow smears from a P falciparum–infected Indian patient by immunofluorescence microscopy. Gametocytes stained with antibodies against the gametocyte-specific protein Pf11-1 (supplemental Figure 1) were detected within cells that were positive for the erythroid lineage–specific GPA staining (Figure 3A). About half of the observed gametocytes were inside nucleated cells (Figure 3B). These findings confirm that gametocytes can develop in bone marrow erythroblasts in vivo.

In vivo imaging of gametocytes within erythroblasts. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of gametocyte-infected erythroblasts on methanol-fixed bone marrow smears from a P falciparum–infected patient. Gametocytes were stained with anti–Pf11-1 antibody (green), and erythroblasts were stained with anti-GPA labeling the erythroid membrane (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (i-ii) Stage I-II gametocyte inside erythroblast. (iii-iv) Stage III-IV gametocyte inside erythroblast. (v) Stage I-II gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. (vi) Stage III-IV gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. (vii) Stage V gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. Gametocyte stages were evaluated based on the size and the shape of P11-1+ cells. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of P11-1+ cells in 3 bone marrow smears from the same patient. The absolute numbers of observed cells are indicated, with the percentages in parentheses.

In vivo imaging of gametocytes within erythroblasts. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of gametocyte-infected erythroblasts on methanol-fixed bone marrow smears from a P falciparum–infected patient. Gametocytes were stained with anti–Pf11-1 antibody (green), and erythroblasts were stained with anti-GPA labeling the erythroid membrane (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (i-ii) Stage I-II gametocyte inside erythroblast. (iii-iv) Stage III-IV gametocyte inside erythroblast. (v) Stage I-II gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. (vi) Stage III-IV gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. (vii) Stage V gametocyte inside reticulocyte or erythrocyte. Gametocyte stages were evaluated based on the size and the shape of P11-1+ cells. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of P11-1+ cells in 3 bone marrow smears from the same patient. The absolute numbers of observed cells are indicated, with the percentages in parentheses.

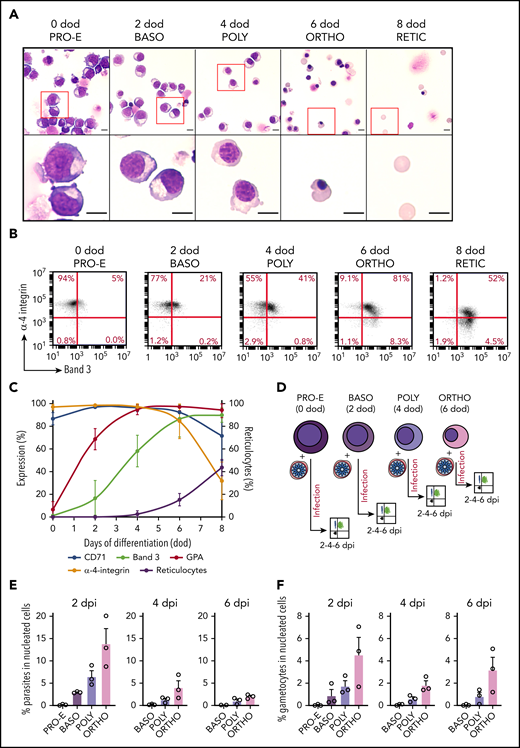

Intraerythroblastic gametocyte development occurs from the polychromatic stage

Terminal erythroid differentiation in vitro usually takes 8 to 10 days from proerythroblasts to reticulocytes.29 Thus, erythroblast infection should theoretically take place during the early stages of terminal erythropoiesis to allow complete development of immature gametocytes in nucleated cells; however, a previous study reports that orthochromatic cells are the earliest stages that may be invaded by P falciparum.18 To determine whether parasites could infect erythroblasts earlier in the erythropoiesis, we tightly synchronized human primary erythroblasts and infected them at different stages of maturation. Erythroid differentiation was monitored from proerythroblasts to reticulocytes (at 0 day of differentiation [dod], 2 dod, 4 dod, 6 dod, and 8 dod) by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining to determine cell size, cytoplasm basophily, and chromatin condensation (Figure 4A), as well as by flow cytometry to quantify reticulocyte production and expression of the surface markers Band 3, α-4-integrin, CD71, and GPA (Figure 4B-C). Synchronized erythroid precursors were infected at the proerythroblast (0 dod), basophilic (2 dod), polychromatic (4 dod), and orthochromatic (6 dod) stages with the Hsp70-GFP and Pfs16-GFP lines, and parasitemia and gametocytemia were monitored at 2 dpi, 4 dpi, and 6 dpi (Figure 4D). First, we observed that parasite invasion could occur from basophilic stages; however, gametocytes do not develop further in these early stages, perhaps as a result of the low hemoglobin content (Figure 4E). Therefore, only polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts sustained parasite and gametocyte development until 6 dpi (Figure 4E-F). These results indicate that the maturation duration of gametocytes in erythroblasts (∼10 days, consistent with the maturation time in erythrocytes3,30 ) is longer than the time usually required by uninfected erythroblasts to develop from orthochromatic stages to reticulocytes in vitro (∼3-4 days).31 Therefore, our data suggest that parasites must prevent or delay the differentiation of erythroblasts into reticulocytes to complete their development in nucleated cells.

Intraerythroblastic gametocyte development occurs from the polychromatic stage. (A) Morphological analysis of developing erythroblasts was performed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining from 0 dod to 8 dod; a representative experiment is shown. Erythroblasts were primarily at the proerythroblast stage (PRO-E) at 0 dod, the basophilic stage (BASO) at 2 dod, the polychromatic stage (POLY) at 4 dod, the orthochromatic stage (ORTHO) at 6 dod, and the reticulocyte stage (RETIC) at 8 dod. The red boxes (upper panels) are shown at higher magnification (lower panels). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Representative experiment of erythroblast differentiation monitored by flow cytometry from 0 dod to 8 dod by cell surface expression of Band 3 and α-4-integrin. (C) Evolution of cell surface markers CD71, Band 3, GPA, and α-4-integrin and of reticulocyte rate measured by flow cytometry during terminal erythropoiesis. (D) Diagram illustrating the infection protocol of synchronized erythroblasts. At 40 hpi, synchronized schizonts were added to proerythroblasts, as well as basophilic, polychromatic, and orthochromatic erythroblasts, at an MOI of 2. Infected erythroblasts were analyzed by flow cytometry at 2, 4, and 6 dpi. Total parasitemia (E) and gametocytemia (F) in erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi, 4 dpi, and 6 dpi after infection of erythroblasts from each stage with the Hsp70-GFP and Pfs16-GFP lines. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Intraerythroblastic gametocyte development occurs from the polychromatic stage. (A) Morphological analysis of developing erythroblasts was performed by May-Grünwald Giemsa staining from 0 dod to 8 dod; a representative experiment is shown. Erythroblasts were primarily at the proerythroblast stage (PRO-E) at 0 dod, the basophilic stage (BASO) at 2 dod, the polychromatic stage (POLY) at 4 dod, the orthochromatic stage (ORTHO) at 6 dod, and the reticulocyte stage (RETIC) at 8 dod. The red boxes (upper panels) are shown at higher magnification (lower panels). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Representative experiment of erythroblast differentiation monitored by flow cytometry from 0 dod to 8 dod by cell surface expression of Band 3 and α-4-integrin. (C) Evolution of cell surface markers CD71, Band 3, GPA, and α-4-integrin and of reticulocyte rate measured by flow cytometry during terminal erythropoiesis. (D) Diagram illustrating the infection protocol of synchronized erythroblasts. At 40 hpi, synchronized schizonts were added to proerythroblasts, as well as basophilic, polychromatic, and orthochromatic erythroblasts, at an MOI of 2. Infected erythroblasts were analyzed by flow cytometry at 2, 4, and 6 dpi. Total parasitemia (E) and gametocytemia (F) in erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry at 2 dpi, 4 dpi, and 6 dpi after infection of erythroblasts from each stage with the Hsp70-GFP and Pfs16-GFP lines. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean.

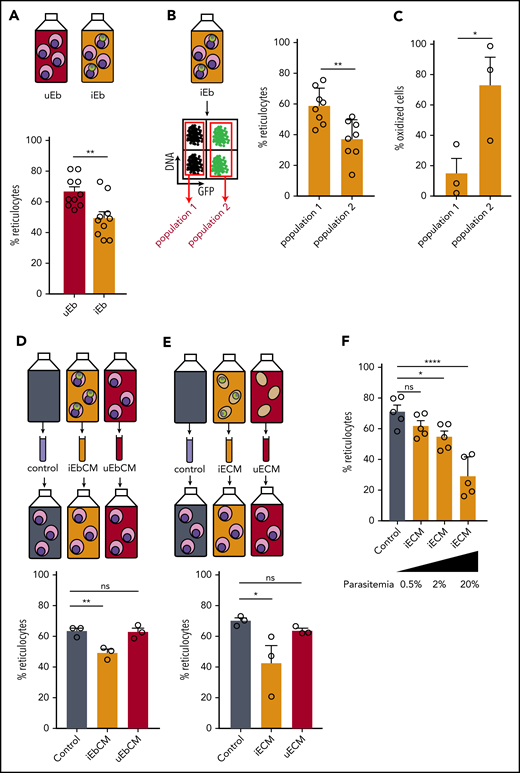

P falciparum infection induces a delay in erythroid maturation and oxidative stress in erythroblasts

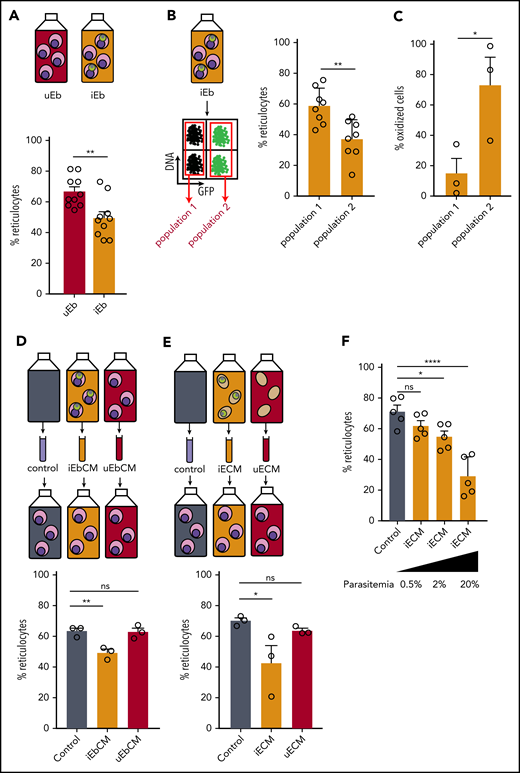

To address whether P falciparum induces a delay in erythroid maturation, we used flow cytometry to measure the impact of infection on the conversion of orthochromatic erythroblasts into reticulocytes (supplemental Figure 5A). At 2 dpi, reticulocytes made up 40% of cells in the infected erythroblast culture vs 48.3% in the uninfected culture; at 8 dpi, the frequency was 49.5% vs 66.7%, respectively (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 5B). This observation suggests that the differentiation of erythroblasts into reticulocytes is delayed by Plasmodium parasites. More precisely, at 8 dpi, the reticulocyte rate in infected cells was 37% vs 58% in uninfected cells within the same infected culture, indicating that gametocytes impede the maturation of their host cell (Figure 5B). Among many factors affecting erythropoiesis, oxidative stress in erythroblasts has been shown to negatively impact enucleation and reticulocyte rate.32 To examine whether the gametocyte-induced delay in erythropoiesis was related to an increase in oxidative stress in erythroblasts, we monitored the oxidation of erythroblasts using DHE at 2 dpi in the Pfs16-GFP line. Within the same infected culture, fivefold more infected erythroblasts were oxidized compared with uninfected erythroblasts at 2 dpi (Figure 5C). These results show that parasite infection induces oxidation of erythroid precursors in vitro, which could be linked to the delay in erythroblast maturation.

P falciparum infection induces a delay in erythroid maturation and oxidative stress in erythroblasts. (A) Percentage of reticulocytes in uninfected erythroblast culture (uEb) or infected erythroblast culture (iEb) was evaluated by flow cytometry at 8 dpi. (B) Percentage of reticulocytes in the population of noninfected cells (population 1) or Pfs16-GFP–infected cells (population 2) within an infected erythroblast culture at 8 dpi. (C) Percentage of oxidized erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry with DHE staining in the population of uninfected cells (Population 1) or Pfs16-GFP–infected cells (Population 2) in an infected erythroblast culture at 2 dpi. (D-E) Percentage of reticulocytes in uninfected erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of conditioned medium obtained with a culture of infected erythroblasts (iEbCM, D), uninfected erythroblasts (uEbCM, D), infected erythrocytes (iECM, E), uninfected erythrocytes (uECM, E), or control medium (Control). (F) Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of iECM obtained with parasite cultures at 0.5%, 2%, or 20% parasitemia or with control medium. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. ****P < .0001, **P < .01, *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant difference.

P falciparum infection induces a delay in erythroid maturation and oxidative stress in erythroblasts. (A) Percentage of reticulocytes in uninfected erythroblast culture (uEb) or infected erythroblast culture (iEb) was evaluated by flow cytometry at 8 dpi. (B) Percentage of reticulocytes in the population of noninfected cells (population 1) or Pfs16-GFP–infected cells (population 2) within an infected erythroblast culture at 8 dpi. (C) Percentage of oxidized erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry with DHE staining in the population of uninfected cells (Population 1) or Pfs16-GFP–infected cells (Population 2) in an infected erythroblast culture at 2 dpi. (D-E) Percentage of reticulocytes in uninfected erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of conditioned medium obtained with a culture of infected erythroblasts (iEbCM, D), uninfected erythroblasts (uEbCM, D), infected erythrocytes (iECM, E), uninfected erythrocytes (uECM, E), or control medium (Control). (F) Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of iECM obtained with parasite cultures at 0.5%, 2%, or 20% parasitemia or with control medium. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. ****P < .0001, **P < .01, *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant difference.

Parasite-conditioned medium induces a delay in erythroid maturation

P falciparum has been shown to affect host cells by modifying the culture medium.33,34 Because the reticulocyte rate from uninfected erythroblasts was lower in infected culture compared with uninfected culture (supplemental Figure 5B), we hypothesized that parasites hamper the maturation of their host cells, as well as induce a bystander effect on the other uninfected cells in the culture. Thus, the delay in erythroblast maturation may also be due to parasite-derived factors secreted in the medium. To address this hypothesis, uninfected orthochromatic erythroblasts were exposed to a medium conditioned by a culture of Plasmodium-infected erythroblasts (iEbCM). After 8 days, the reticulocyte rate from erythroblasts cultivated in the iEbCM was significantly lower than that of erythroblasts cultivated with regular medium (control) or with medium conditioned by uninfected erythroblasts (uEbCM). These results indicate a parasite-specific effect on erythropoiesis (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 6A). A significant decrease in reticulocyte production was also induced by addition of iECM (Figure 5E; supplemental Figure 6B). Because of the scarcity of human primary erythroblasts, iECM was used for additional experiments. The delayed effect of iECM was observed from 4 days of culture and was dependent on the parasitemia in the culture providing the conditioned medium (Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 7A). We then addressed the effect of medium conditioned by immature GIEs (supplemental Figure 7B) or by erythrocytes infected with asexual parasites from a line that has lost the ability to produce gametocytes (supplemental Figure 7C).21 Both conditions triggered similar delays in reticulocyte production, indicating that the observed effect was not dependent on the parasite stage.

To decipher whether this delay was due to an enrichment in specific parasite-secreted factors or to a depletion in nutrients essential for erythroblast development, iECM was supplemented with several components of the erythroblast culture medium: serum substitute, erythropoietin, l-glutamine, a pool of amino acids, human serum, or a pool of all of these components. However, none of these conditions was able to reverse the delay phenotype (supplemental Figure 8). Although we have not exhaustively tested all of the medium components, these data support the hypothesis that erythroid cellular development is affected by parasite-secreted factors rather than the consumption of essential nutrients by the parasite.

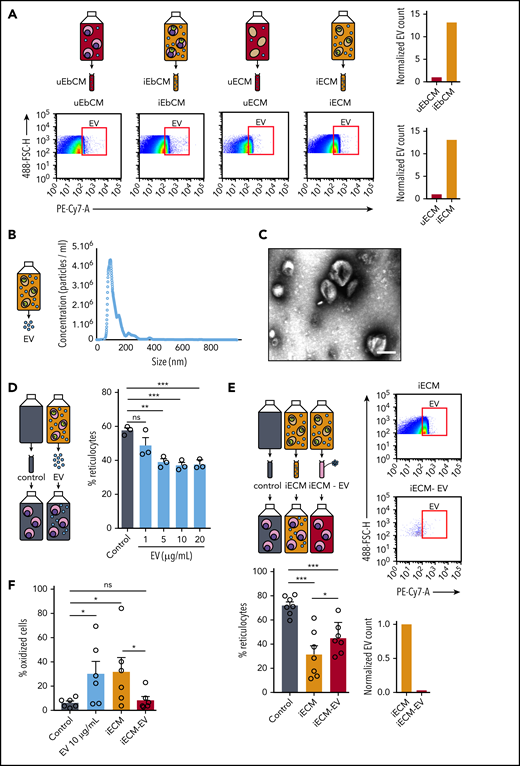

Parasite-derived EVs delay erythropoiesis and induce oxidative stress

Upon infection with P falciparum, erythrocytes produce EVs.35,36 Because infected erythrocyte–derived EVs have been shown to directly affect host cells by altering the vascular functions of endothelial cells37 or by activating immune cells,35,38 we addressed whether EVs could affect erythroid precursors. First, flow cytometry quantification of GPA-labeled EVs (supplemental Figure 9) showed that parasite infection increases the production of EVs by erythroblasts to a similar level as that by erythrocytes (Figure 6A). Electron microscopy analysis and NTA of EVs purified from a culture of infected erythrocytes confirmed the presence of vesicular structures with characteristic EV size distribution primarily ranging from 70 nm to 200 nm, with a main peak near 130 nm (Figure 6B-C; supplemental Figure 10). Importantly, adding purified EVs to uninfected erythroblasts for 8 days significantly decreased the reticulocyte rate, suggesting that EVs negatively affect erythropoiesis (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 11A). To confirm this result, erythroid precursors were cultivated for 8 days with iECM or with iECM − EV. After validating that iECM − EV contained 500-fold fewer EVs than complete iECM, we observed that EV depletion attenuated the iECM-induced delay in erythropoiesis (Figure 6E; supplemental Figure 11B). These experiments provide evidence that parasite-secreted EVs contribute to the erythropoiesis delay induced by P falciparum. Next, we examined whether the EV-induced delay in erythropoiesis was related to an increase in oxidative stress in erythroblasts. Importantly, fivefold more erythroblasts cultivated with 10 µg/mL purified EVs or with iECM were oxidized compared with erythroblasts cultivated with control medium or with iECM − EV (Figure 6F). These results show that EVs induce the same level of oxidation of erythroid precursors as does parasite infection. Both mechanisms may contribute to the delay in erythroblast maturation observed previously.

Parasite-derived EVs delay the erythroid maturation and induce oxidative stress. (A) EVs in conditioned medium obtained with a culture of uninfected erythroblasts (uEbCM), infected erythroblasts (iEbCM), uninfected erythrocytes (uECM) or infected erythrocytes (iECM) were observed and quantified by flow cytometry with a GPA-PC7 labeling. EV counts in iEbCM and iECM are normalized to uEbCM and uECM, respectively. Gating strategy is shown in supplemental Figure 7. (B) The size distribution of EVs purified from a culture of infected erythrocytes was determined by NTA. (C) EVs purified from a culture of infected erythrocytes were observed by electron microscopy with a negative staining. Scale bar, 100 nm. (D) Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of 1, 5, 10, or 20 µg/mL EVs or control medium. (E) EVs in iECM or in iECM − EV were observed and quantified by flow cytometry with GPA-PC7 labeling. Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblasts at 8 days after addition of iECM, iECM − EV, or control medium (lower left panel). (F) Percentage of oxidized erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry with DHE staining 2 days after addition of 10 µg/mL EVs, iECM, iECM − EV, or control medium. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. ***P < .001, **P < .01, *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant difference.

Parasite-derived EVs delay the erythroid maturation and induce oxidative stress. (A) EVs in conditioned medium obtained with a culture of uninfected erythroblasts (uEbCM), infected erythroblasts (iEbCM), uninfected erythrocytes (uECM) or infected erythrocytes (iECM) were observed and quantified by flow cytometry with a GPA-PC7 labeling. EV counts in iEbCM and iECM are normalized to uEbCM and uECM, respectively. Gating strategy is shown in supplemental Figure 7. (B) The size distribution of EVs purified from a culture of infected erythrocytes was determined by NTA. (C) EVs purified from a culture of infected erythrocytes were observed by electron microscopy with a negative staining. Scale bar, 100 nm. (D) Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblast culture at 8 days after addition of 1, 5, 10, or 20 µg/mL EVs or control medium. (E) EVs in iECM or in iECM − EV were observed and quantified by flow cytometry with GPA-PC7 labeling. Percentage of reticulocytes in erythroblasts at 8 days after addition of iECM, iECM − EV, or control medium (lower left panel). (F) Percentage of oxidized erythroblasts was evaluated by flow cytometry with DHE staining 2 days after addition of 10 µg/mL EVs, iECM, iECM − EV, or control medium. Circles indicate the number of independent experiments, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. ***P < .001, **P < .01, *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant difference.

Discussion

Unraveling the retention mechanisms of immature GIEs in the bone marrow parenchyma is necessary to decipher P falciparum transmission biology. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain gametocyte localization in the bone marrow. Sequestration of gametocytes in this niche may be mediated by cytoadhesion of immature GIEs to bone marrow mesenchymal cells,10 or it may depend on mechanical retention, which could result from the high rigidity of immature GIEs.11,25,39 In this study, we addressed the new hypothesis that gametocytes could mature within erythroblasts bound to the nursing macrophages of erythroblastic islands. We demonstrate that Plasmodium infection impedes enucleation of primary erythroblasts, thereby allowing immature gametocytes to complete their full development within these nucleated cells. Once maturation is complete inside reticulocytes, stage V gametocytes can reach the blood circulation, where they are available for uptake and further transmission by mosquitoes. The ability to undergo a temperature-dependent release of round gametes from their reticulocyte host substantiates the functional maturity of gametocytes and suggests that they are transmissible to mosquitoes.40 Importantly, these observations are supported by in vivo analyses of bone marrow smears from a malaria-infected patient.

This discovery of a new host cell for P falciparum sheds light on a poorly understood part of the parasite life cycle and raises new questions about the cross talk between gametocytes and these nucleated cells. In infected erythrocytes, it is well known that P falciparum gametocytes drastically modify the structural and mechanical properties of the host cell membrane. This remodeling is induced by the export of several parasite-expressed proteins and plays a key role in gametocyte survival, chemosensitivity, and recognition by the immune system.41 For instance, gametocyte-induced remodeling of the erythrocyte membrane regulates deformability and permeability of the infected erythrocyte, 2 features involved in the ability of gametocytes to persist in circulation and their susceptibility to antimalarial drugs, respectively.11,42 In addition, several parasite proteins exposed at the GIE surface have recently been proposed as target antigens for transmission-blocking vaccines.9 Our findings indicate that gametocytogenesis progresses in a similar manner in erythroblasts and their mature counterparts. Further studies should address whether gametocytes export their proteins to the membrane of the infected erythroblast and whether these proteins influence the mechanical, adhesive, and immunogenic properties of the nucleated host cells. Such remodeling has crucial implications for how to target gametocytes in drug- or vaccine-based interventions, which must now be reevaluated in the light of gametocyte development within erythroblasts.

The most striking impact of gametocyte development within erythroblasts is the inhibition of their conversion into reticulocytes. This host cell subversion is redolent of previous findings showing that Plasmodium vivax parasites accelerate the aging of infected reticulocytes.43 Taken together, these observations highlight how Plasmodium hijacks the maturation of its host cell to complete its own development. This is in line with the characteristic manipulation of mammalian cell functions by protozoan parasites.44 Impaired erythropoiesis observed in P falciparum–infected erythroblasts results from a direct effect of gametocytes on their host cell, as well as parasite factors secreted in the extracellular environment. Gametocytes might delay erythroid maturation by exporting proteins to the erythroblast nucleus. In erythrocytes, gametocytes express a wide range of proteins, and >10% are exported to the host cell.45 Although most of these proteins lack any functional annotation, the presence of a nuclear localization signal in the sequence of some of them suggests that these proteins might interfere with the regulation of genes in erythroblasts. Such mechanisms could conceivably affect erythroid differentiation. We also demonstrate that parasite-derived EVs play a key role in impairing the erythroid maturation process. Although EVs produced by protozoan parasites have already been shown to contribute to the manipulation of their host cells,37,46 our results demonstrate, for the first time, an effect of Plasmodium-secreted vesicles on erythropoiesis. However, the molecular identity of the EV-embedded factor(s) triggering this delay remains to be identified. Such factors could be nucleic acids or proteins, because EVs contain microRNAs affecting host cells,37 and the recent protein-dependent effect of parasite-conditioned medium has been shown to impair erythroblast differentiation.47 Among the multiple outcomes that parasite infection and EVs may induce in erythroid precursors, our results show that they cause oxidative stress. This is consistent with the results of a transcriptomic assay, in which coculture and infection of erythroid precursors with P falciparum asexual stages increased the expression of several genes involved in the NFR2-mediated oxidative stress response.48 Because oxidative stress can lead to inhibition of erythroid maturation and dyserythropoiesis, such an increase in oxidation may be responsible for the reported delay in erythroblast enucleation.32 Importantly, dyserythropoiesis is a major contributor to malarial anemia19 and has been associated with a higher prevalence of gametocytes in bone marrow, suggesting a relationship between hematological disturbances and gametocyte development in this tissue.4 Therefore, erythroblast infection by gametocytes and parasite-derived EVs secreted in the bone marrow parenchyma may be involved in erythroid disorders in patients infected with P falciparum. Thus, our results imply that therapeutic and vaccine interventions targeting gametocytes would prevent transmission, as well as decrease anemia in malaria patients.

Collectively, our findings shed light on a new mechanism that may contribute to the maintenance of immature gametocytes in the bone marrow extravascular space, and they provide new insights into the processes by which Plasmodium parasites subvert their host cell and may interfere with erythropoiesis in malaria patients. Future therapies aimed at disrupting these mechanisms may help to decrease transmission in endemic areas, as well as treat malarial anemia.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Catherine Lavazec (catherine.lavazec@inserm.fr).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the CYBIO Flow Cytometry core facility, the IMAG’IC imaging core facility, and the Electron microscopy core facility (Institut Cochin), for technical help. Electron microscopy was also carried out at ICM-QUANT Bioimaging core facility, Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle Épinière-Hospital Pitié Salpêtrière. The authors are grateful to Odile Mercereau-Puijalon and Micheline Guillotte for providing the anti–Pf11-1 antibodies and the VarO parasite line. They thank Jayamalini Jeremias for technical support and Naomi Taylor, Silvia Portugal, Laurent Renia, Bjorn Kafsack, Robert Ménard, and Frédéric Ariey for fruitful discussions.

This work was supported by CNRS, INSERM, the French Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, and the Laboratory of Excellence GR-Ex (ANR-11-LABX-0051), funded by the IdEx program “Investissements d’Avenir” of the French National Research Agency (ANR-18-IDEX-0001) (G.N., C.L., and F. Verdier). This study was also funded by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (“Equipe FRM” EQ20170336722) (C.L.), the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U19AI089676) (S.C.W.), and the UK Medical Research Council (MR/S009450/1) (S.C.W.). This work was supported in part by French Parasitology consortium grant ParaFrap (ANR‐11‐LABX0024) (D.M.), and P.A.S. was supported by an Agence Nationale de la Recherché (ANR) grant “HypEpicC” to D.M.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Authorship

Contribution: G.N., F. Verdier, and C.L. conceived the project; G.N., C.R., F. Volpe, F.D., P.A.S., B.M.-Z., P.V., M.A., A.L., and C.L. performed experiments; P.B., N.A., R.M.M., J-J.L.-R., A.M.M., D.M., S.S., F.G., A.K.A.S., and S.C.W. contributed resources or data; and G.N. and C.L. wrote the article, with major input from F. Verdier and S.C.W.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Catherine Lavazec, INSERM U1016, CNRS UMR 8104, Université de Paris, 22 Rue Méchain, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: catherine.lavazec@inserm.fr.

REFERENCES

Author notes

F. Verdier and C.L. contributed equally to this work.