Key Points

A Lys311-to-glutamic acid substitution in the third kringle domain of Plg is associated with HAE.

Plm-Glu311 catalyzes BK release from HK and LK independently of PKa.

Abstract

Patients with hereditary angioedema (HAE) experience episodes of bradykinin (BK)-induced swelling of skin and mucosal membranes. The most common cause is reduced plasma activity of C1 inhibitor, the main regulator of the proteases plasma kallikrein (PKa) and factor XIIa (FXIIa). Recently, patients with HAE were described with a Lys311 to glutamic acid substitution in plasminogen (Plg), the zymogen of the protease plasmin (Plm). Adding tissue plasminogen activator to plasma containing Plg-Glu311 vs plasma containing wild-type Plg (Plg-Lys311) results in greater BK generation. Similar results were obtained in plasma lacking prekallikrein or FXII (the zymogens of PKa and FXIIa) and in normal plasma treated with a PKa inhibitor, indicating Plg-Glu311 induces BK generation independently of PKa and FXIIa. Plm-Glu311 cleaves high and low molecular weight kininogens (HK and LK, respectively), releasing BK more efficiently than Plm-Lys311. Based on the plasma concentrations of HK and LK, the latter may be the source of most of the BK generated by Plm-Glu311. The lysine analog ε-aminocaproic acid blocks Plm-catalyzed BK generation. The Glu311 substitution introduces a lysine-binding site into the Plg kringle 3 domain, perhaps altering binding to kininogens. Plg residue 311 is glutamic acid in most mammals. Glu311 in patients with HAE, therefore, represents reversion to the ancestral condition. Substantial BK generation occurs during Plm-Glu311 cleavage of human HK, but not mouse HK. Furthermore, mouse Plm, which has Glu311, did not liberate BK from human kininogens more rapidly than human Plg-Lys311. This indicates Glu311 is pathogenic in the context of human Plm when human kininogens are the substrates.

Introduction

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a genetic condition affecting 1 in 50 000 to 100 000 individuals.1 Patients with HAE experience recurring episodes of soft tissue swelling involving subcutaneous tissues (hands and face), oropharyngeal mucosa, the genitals, and the gastrointestinal tract.1-3 The underlying cause in most cases is dysregulation of the plasma kallikrein-kinin system (KKS).2,4,5 The KKS is composed of the zymogens prekallikrein (PK) and factor XII (FXII) and the cofactor/substrate high molecular weight kininogen (HK).6-8 PK and FXII reciprocally convert each other to the proteases plasma kallikrein (PKa) and FXIIa.6-10 PKa cleaves HK to release the vasoactive nonapeptide bradykinin (BK).4-8 The effects of BK are mediated through the B2 receptor, which is constitutively expressed in many tissues.11,12 Basal BK production likely contributes to setting normal blood vessel tone and permeability,13,14 while higher concentrations at injury sites facilitate vascular leak, tissue swelling, and pain sensation.4-8 In HAE, soft tissue swelling from excessive BK production distinguishes the disorder from the more common histamine-driven edema associated with allergic reactions.1-5

The primary regulator of PKa and FXIIa is the serpin C1 inhibitor (C1-INH).1-3,15 In most patients with HAE, plasma C1-INH activity is <50% of normal.1-3 However, at least 10% of those with HAE have normal C1-INH activity.2,10,16-19 Lysine or arginine substitutions for Thr309 in FXII were reported in patients with HAE with normal C1-INH in 200620 and have subsequently been identified in >150 families.16-19 FXII-Thr/Arg309 creates a protease cleavage site that facilitates generation of a truncated FXII (ΔFXII), which accelerates reciprocal activation with PK and overwhelms the inhibitory capacity of C1-INH.6,21 In 2018, 2 groups reported a Lys311 to glutamic acid substitution in the fibrinolytic zymogen plasminogen (Plg) in patients with HAE with normal C1-INH activity who lacked FXII-Thr309Lys/Arg.22,23 Plg-Glu311 has now been reported in ∼150 patients in 33 families.16-19 We prepared recombinant Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311 and their activated plasmin (Plm) forms (Plm-Lys311 and Plm-Glu311) and tested their effects on BK production in purified protein- and blood-based systems. We conclude that Plm-Glu311 is a potent kininogenase that catalyzes BK release from human HK and the related protein low molecular weight kininogen (LK) independently of PKa and FXIIa.

Methods

Materials

Materials used were as follows: normal human plasma (Precision BioLogic); human plasmas lacking FXII, FXI, PK, or kininogen (George King Biomed); FXII, FXIIa, PK, PKa, HK, human and mouse Plgs, human and mouse Plms, and corn trypsin inhibitor (Enzyme Research Laboratory); fibrinogen and α-thrombin (Haematologic Technologies); LK, soybean trypsin inhibitor, ɛ-aminocaproic acid (ɛ-ACA; Sigma-Aldrich); tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase; Genentech); S2302 (H-d-prolyl-l-phenylalanyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride; DiaPharma); polyclonal horseradish peroxidase–conjugated immunoglobulin (IgG) to hemagglutinin tag (HA) and rabbit anti-BK polyclonal IgG (Invitrogen); PKa inhibitor KV999272 (formerly VA999272) was previously described24; and BK (Eurofins Discover X, Fremont, CA) and kallidin standards (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan).

Recombinant proteins

Plgs and Plms

Complementary DNAs for wild-type human Plg (Plg-Lys311) and Plg with glutamic acid (Plg-Glu311) or alanine (Plg-Ala311) substitutions at amino acid 311 were expressed in Expi293 cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plgs were concentrated from conditioned media by binding to lysine-sepharose, purified further by ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography and converted to Plm (Plm-Lys311 and Plm-Glu311) by incubation with urokinase immobilized on sepharose at 37°C.

Kininogens

cDNAs encoding human HK and LK (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site), full-length mouse HK (mHK1; supplemental Figure 2), and mouse HK lacking domain 5 and part of domain 6 (mHK3; supplemental Figure 3) in expression vector pJVCMV9,10 were modified by adding an HA (Tyr-Pro-Tyr-Asp-Val-Pro-Asp-Tyr-Ala) tag to the C terminus. Kininogens were expressed in HEK293 cells and purified by chromatography using anti-HA IgG coupled to agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Pierce Protein Biology). Preparations of recombinant kininogens are shown in supplemental Figure 4. Preparation of human FXII lacking amino acids 1 to 309 (ΔFXII) has been previously reported.10

Chromogenic assays

All reactions were conducted in 96-well PEG-20000–coated plates in 100 μL of reaction buffer (20 mM of N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [pH, 7.4], 100 mM of NaCl, 0.1% PEG-8000, and 10 mM of ZnCl2) at 37°C. For all experiments involving enzyme activation or activity, the term vehicle refers to this buffer.

Discontinuous assays

Plg, FXII, or PK (200 nM) was incubated with tPA (20 nM), Plm (125 nM), FXIIa (20 nM), or PKa (20 nM). In some experiments, before addition of enzymes and substrates, fibrinogen (200 μg/mL) and thrombin (50 nM) were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes to form fibrin. Thrombin was inhibited with hirudin (250 μM), followed by addition of enzymes and substrates. At various times, aliquots were removed for activity testing. For measuring PKa or FXIIa generation by Plm, reactions were stopped with 2 μM of α2-antiplasmin for reactions with PKa or 3.3 μM of aprotinin for reactions with FXIIa. For measuring Plm generation by FXIIa and PKa, reactions were stopped with 600 nM of corn trypsin inhibitor or 10 μM of KV999272, respectively. S-2302 was added to a final concentration of 200 μM, and changes in optical density at 405 nm were measured. Results were converted to FXIIa, PKa, and Plm concentrations using control curves constructed with purified enzymes.

Continuous assays

Fibrinogen (200 μg/mL) and thrombin (50 nM) were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes, after which thrombin was inhibited with hirudin (250 μM). Plg (200 nM) and S-2302 (200 μM) were added with or without tPA (300 pM), and changes in optical density at 405 nm were followed.

Kinin assay

Normal, FXII-deficient, or PK-deficient plasma was supplemented with captopril (500 μM) and Plg (600 nM), and reactions (40-μL volumes) were started with different concentrations of tPA or ΔFXII at 37°C. At various times, 3-μL reaction volumes were transferred to 12 μL of ice-cold ethanol. Samples were clarified by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 minutes. Kininogen-deficient plasma was supplemented with plasma-derived human HK (640 nM), LK (2.3 μM) or both and then treated in a similar manner to other plasmas. For purified protein assays, HK, LK, mHK1, or mHK3 (200 nM) were incubated with different concentrations of PKa or Plm in reaction buffer (150 μL) at 37°C. At various times, 10-μL volumes were transferred into 90 μL of ice-cold ethanol and placed at −80°C overnight. Samples underwent clarification by centrifugation at 10 000g for 1 hour. For all reactions, kinins were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.). For any experiment involving BK release, the term vehicle refers to 20 mM of tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)-HCl and 136 mM of NaCl (pH, 7.4).

Mass spectroscopy

Purified kininogen samples were prepared in the same manner as for the kinin ELISA. For all analytes, ionization was achieved using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI). Analytes were deposited with matrix on MALDI targets. Matrix 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (Sigma) was purified by recrystallization from hot water. Matrix solution was prepared with recrystallized 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (15 mg/dL) in a water/acetonitrile/formic acid ratio of 1:1:0.1. Matrix solution (1 μL) was spotted onto the MALDI target with 1 μL of analyte sample and allowed to dry at room temperature. Samples were analyzed in a Bruker AutoFlex (Billerica, MA) mass spectrometer. Mass spectrometry data were collected in positive ion reflectron mode with a mass/charge (m/z) range from 600 to 6000. Spectra are from an average of at least 100 laser shots per sample spot. Mass spectra were analyzed with Compass 1.4 Flex Series software (Bruker Daltonics).

Western blots

Plasma HK (200 nM) with PKa (2 nM), or plasma HK (800 nM) with Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311(250 nM) was incubated in reaction buffer at 37°C. At various times, aliquots were removed into nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and size fractionated on 10% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were either stained with GelCode Blue or transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with an anti-human BK antibody. Detection was by chemiluminescence.

Coprecipitation

Two micrograms of Plg or Plm (active site inhibited with FPR-chloromethylketone) was incubated with recombinant human HK or LK (2 μg) for 30 minutes in 500 μL of Tris-buffered saline (20 mM of Tris-HCl [pH, 7.4] and 100 mM of NaCl). Kininogens were precipitated with anti-HA magnetic beads (Pierce) and washed 3 times with Tris-buffered saline/0.05% Tween-20. Proteins were eluted with SDS nonreducing sample buffer and size fractionated on 10% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were stained with GelCode Blue (Pierce).

Surface plasmon resonance

HK was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip using amine coupling. Binding of Plg or Plm (25-400 nM) to HK was assessed by a single-cycle assay at 25°C on a Biacore T200 device (Cytiva) in running buffer (10 mM of N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [pH, 7.4], 150 mM of NaCl, 50 μM of EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20). The data were fitted with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using Biacore T200 evaluation software (Biacore AB), which was also used to calculate kinetic and affinity constants.

Results

Recombinant Plg

Full-length Glu-Plg is converted to Lys-Plg by removal of the N-terminal PAN domain (Figure 1A, left). Glu- and Lys-Plg are converted to Plm by cleavage of the Arg561-Val562 peptide bond. Because Lys-Plg is in an open conformation with a more accessible activation cleavage site, it is activated by tPA ∼10-fold faster than Glu-Plg in the absence of fibrin (Figure 1B). Recombinant Plg-Lys311, Plg-Glu311, and their Plm forms were compared with plasma Glu-Plg and Glu-Plm, as shown in Figure 1A (center and right). Plg-Ala311 (supplemental Figure 5) was prepared as a control. Although the recombinant Plgs are Glu-Plgs,25,26 they are activated similarly to Lys-Plg (Figure 1C). This is due to glycosylation differences near the activation site in Glu-Plg expressed in HEK293 cells (isoform 1) and plasma-derived Glu-Plg (mostly isoform 2).25,26 To account for this, Plg-Glu311 and Plg-Ala311 were compared with wild-type Plg-Lys311, rather than plasma-derived Glu-Plg, in activity assays. Plg bound to fibrin adopts an open conformation that accelerates activation by tPA (supplemental Figure 6A). Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311 are activated comparably to plasma-derived Glu-Plg in the presence of fibrin (supplemental Figure 6B).

Recombinant Plg activation and effects on BK generation in normal plasma. (A) Coomassie Blue stained SDS–polyacrylamide gels of plasma-derived Plgs (left), recombinant Plgs (center), and recombinant Plms (right). Shown in the center and right panels are 2-μg samples of plasma-derived Glu-Plg/Plm (P), Plg/Plm-Lys311 (Lys), and Plg/Plm-Glu311. Positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are shown at the left of each figure, and positions of standards for zymogen Plg (Z) and the heavy (HC) and light chains (LC) of Plm are shown on the right. (B) Activation of 200 nM of plasma-derived Glu-Plg (green), Lys-Plg (orange), or vehicle (no Plg; purple) by 20 nM of tPA in reaction buffer. (C) Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Glu311 (red), Plg-Ala311 (green), or vehicle (purple), 200 nM each, were incubated in reaction buffer with 20 nM of tPA. In panels B and C, at indicated times, samples were removed for measurement of Plm by chromogenic assay. (D) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Ala311 (green), Plg-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple) after addition of tPA (final, 125 nM). (E) Controls for reactions in panel D. BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Glu311 and tPA (light green), Plg-Glu311 alone (blue), tPA alone (red), or vehicle (purple). (F) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Glu311 (600 nM) after adding tPA to 250 (lavender), 125 (steel blue), 62.5 (blue) or 50 nM (magenta). (G) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue) or Plg-Glu311 (red) after addition of tPA (various concentrations) and thrombin (50 nM; to generate fibrin). In panels B to D, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panels F and G, results are for single representative experiments.

Recombinant Plg activation and effects on BK generation in normal plasma. (A) Coomassie Blue stained SDS–polyacrylamide gels of plasma-derived Plgs (left), recombinant Plgs (center), and recombinant Plms (right). Shown in the center and right panels are 2-μg samples of plasma-derived Glu-Plg/Plm (P), Plg/Plm-Lys311 (Lys), and Plg/Plm-Glu311. Positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are shown at the left of each figure, and positions of standards for zymogen Plg (Z) and the heavy (HC) and light chains (LC) of Plm are shown on the right. (B) Activation of 200 nM of plasma-derived Glu-Plg (green), Lys-Plg (orange), or vehicle (no Plg; purple) by 20 nM of tPA in reaction buffer. (C) Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Glu311 (red), Plg-Ala311 (green), or vehicle (purple), 200 nM each, were incubated in reaction buffer with 20 nM of tPA. In panels B and C, at indicated times, samples were removed for measurement of Plm by chromogenic assay. (D) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Ala311 (green), Plg-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple) after addition of tPA (final, 125 nM). (E) Controls for reactions in panel D. BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Glu311 and tPA (light green), Plg-Glu311 alone (blue), tPA alone (red), or vehicle (purple). (F) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Glu311 (600 nM) after adding tPA to 250 (lavender), 125 (steel blue), 62.5 (blue) or 50 nM (magenta). (G) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue) or Plg-Glu311 (red) after addition of tPA (various concentrations) and thrombin (50 nM; to generate fibrin). In panels B to D, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panels F and G, results are for single representative experiments.

Plg activation and BK generation in normal plasma

When tPA was added to normal plasma supplemented with recombinant Plg, BK generation was substantially greater with Plg-Glu311 than with Plg-Lys311 or Plg-Ala311 (Figure 1D-E). There was a threshold for inducing measurable BK in this system that required relatively high tPA concentrations (Figure 1F), likely reflecting slow tPA-catalyzed Plg activation in the absence of fibrin and the short plasma half-life of tPA. Adding thrombin to plasma to convert fibrinogen to fibrin led to measurable BK production at a 10-fold lower tPA concentration (Figure 1G), again with more BK generated with Plg-Glu311. The enhanced activity associated with the Glu311 substitution cannot be attributed specifically to loss of Lys311, because Plg-Ala311 did not create the gain-of-function phenotype noted with Plg-Glu311 (Figure 1D).

Plg-Glu311 enhances BK generation independently of PKa and FXIIa

Plm activates FXII.27-30 Increased BK generation in plasma containing Plg-Glu311 may, therefore, reflect enhanced FXII activation by Plm-Glu311.27-30 However, Plm-Glu311 and Plm-Lys311 were comparable, relatively weak, activators of FXII (Figure 2A) and PK (Figure 2B). Furthermore, Plg-Glu311 enhanced BK generation comparably in normal (Figure 2C), PK-deficient (Figure 2D), and FXII-deficient (Figure 2E) plasmas. Rapid HK cleavage may be induced in normal plasma by adding ΔFXII, identified in patients with HAE with FXII-Lys/Arg309 substitutions.10 ΔFXII is activated by PKa ∼40 times faster than FXII, accelerating reciprocal activation of PK.10 Accordingly, ΔFXII-induced BK generation was blocked by the PKa inhibitor KV999272 (Figure 2F).24 In contrast, BK generation induced by adding tPA to plasma containing Plg-Glu311 was unaffected by KV999272 (Figure 2G), consistent with Plm-Glu311 driving BK generation independently of PKa.

Recombinant Plg and the KKS. (A-B) Activation of FXII (A) or PK (B), 200 nM each, by 200 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue), Plm-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple). Reactions without FXII or PK for Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311 are indicated in green and gray, respectively. (C-E) BK generation in normal plasma (C), PK-deficient plasma (D), or FXII-deficient plasma (E) supplemented with 600 nM (final concentration) of Plg-Lys311 (blue) or Plg-Glu311 (red) after addition of tPA (125 nM final concentration). (F) BK generation in normal plasma after addition of ΔFXII (160 nM; lavender), ΔFXII and KV999272 (10 μM; steel blue), or vehicle (light blue). (G) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Glu311 (red and steel blue) or vehicle (lavender) in response to tPA (125 nM) in the absence (red) or presence (steel blue) of 10 μM of KV999272. (H) Activation of Plg-Lys311 (blue, light green, and orange) or Plm-Glu311 (red, purple, and gray), 200 nM each, by 20 nM of tPA (blue and red), PKa (light green and purple), or FXIIa (orange and gray). (I) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple) after addition of ΔFXII (final concentration, 62.5 nM). For reactions in panels A, B, and H, samples were removed at indicated times and protease measured by chromogenic assay. In panels C to G and I, samples were removed at indicated times and BK measured by ELISA. In panels A to H, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panel I, error bars indicate standard errors for 2 experiments.

Recombinant Plg and the KKS. (A-B) Activation of FXII (A) or PK (B), 200 nM each, by 200 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue), Plm-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple). Reactions without FXII or PK for Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311 are indicated in green and gray, respectively. (C-E) BK generation in normal plasma (C), PK-deficient plasma (D), or FXII-deficient plasma (E) supplemented with 600 nM (final concentration) of Plg-Lys311 (blue) or Plg-Glu311 (red) after addition of tPA (125 nM final concentration). (F) BK generation in normal plasma after addition of ΔFXII (160 nM; lavender), ΔFXII and KV999272 (10 μM; steel blue), or vehicle (light blue). (G) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with 600 nM of Plg-Glu311 (red and steel blue) or vehicle (lavender) in response to tPA (125 nM) in the absence (red) or presence (steel blue) of 10 μM of KV999272. (H) Activation of Plg-Lys311 (blue, light green, and orange) or Plm-Glu311 (red, purple, and gray), 200 nM each, by 20 nM of tPA (blue and red), PKa (light green and purple), or FXIIa (orange and gray). (I) BK generation in normal plasma supplemented with Plg-Lys311 (blue), Plg-Glu311 (red), or vehicle (purple) after addition of ΔFXII (final concentration, 62.5 nM). For reactions in panels A, B, and H, samples were removed at indicated times and protease measured by chromogenic assay. In panels C to G and I, samples were removed at indicated times and BK measured by ELISA. In panels A to H, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panel I, error bars indicate standard errors for 2 experiments.

BK generation after KKS activation

PKa can activate Plg by a fibrin-independent mechanism,31,32 suggesting KKS activation could generate Plm that may contribute to BK formation. However, we found that PKa and FXIIa were weak activators of Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311 when compared with tPA (Figure 2H). As shown in Figure 2I, ΔFXII was added to plasma to activate the KKS. Adding Plg-Lys311 or Plg-Glu311 to this system modestly increased BK production that may be slightly greater with Plg-Glu311 than Plg-Lys311. However, this would not account for the difference in magnitude of the effects of Plg-Lys311 or Plg-Glu311 in plasma treated with tPA (Figure 2C-E).

Plm cleaves kininogens

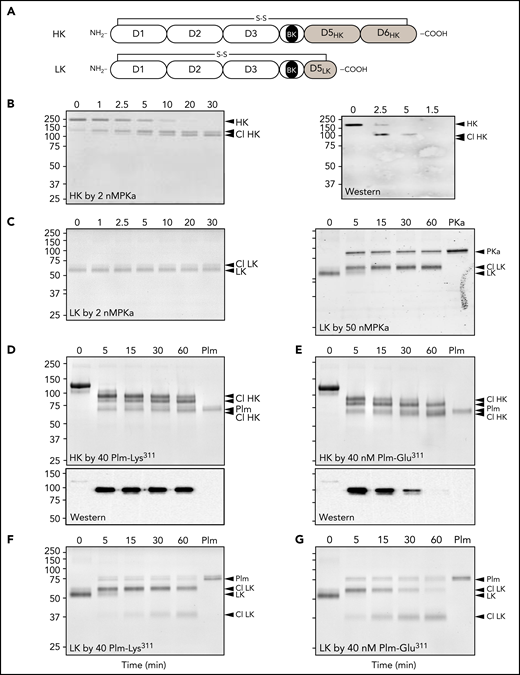

Human plasma contains 2 kininogens, HK and LK, which are encoded by alternatively spliced messenger RNAs from the Kng1 gene.33,34 Sequential cleavage of HK by PKa after Arg371 and Lys362 releases BK (Arg363-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg371), whereas LK cleavage by tissue kallikreins after Arg371 and Met361 releases the decapeptide kallidin (Lys-BK, Lys362-Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg371).35,36 HK and LK each contain a disulfide bond (Cys10-Cys596 and Cys10-Cys389, respectively) that connects the N and C termini of the protein (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 1).36,37 PKa cleavage of the Arg371-Ser372 peptide bond produced a pronounced downward shift in HK migration on nonreducing SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis corresponding to conversion of HK to a linear form (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4). Cleavage of the Lys362-Arg363 bond then released BK, causing an additional subtler downward shift. A western blot using an anti-BK IgG was consistent with the BK sequence remaining associated with HK after 1 cleavage and then being released by the second cleavage (Figure 3B, right). LK cleavage by PKa caused a slight upward shift in migration. A higher PKa concentration was required to observe LK cleavage than that required with HK (Figure 3C).

Kininogen cleavage by Plm. (A) Schematic diagrams of human HK (top) and LK (bottom) showing domain structure and the disulfide bond connecting the N and C termini. The position of the BK nanopeptide is shown in black. (B-G) Coomassie Blue–stained SDS polyacrylamide gels showing HK and LK cleavage. At indicated times, samples were removed into nonreducing sample buffer and size fractionated on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. (B) Time course of HK cleavage by PKa. Human plasma–derived HK (200 nM) was incubated with PKa (2 nM) in reaction buffer at 37°C. The right panel is a western blot of samples from a reaction similar to that in panel D using an antibody to BK. (C) Time course of LK cleavage by PKa. Human plasma–derived LK (200 nM) was incubated with 2 (left) or 50 nM (right) of PKa in reaction buffer at 37°C. (D-E) Human plasma–derived HK (800 nM) incubated with 160 nM of Plm-Lys311 (D) or Plm-Glu311 (E). Bottom shows western blots for samples from reactions in the top using an antibody to BK. (F-G) Human plasma–derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 nM of Plm-Lys311 (D) or Plm-Glu311 (E). For all panels, positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left. Positions of standards for uncleaved HK or LK, cleaved forms of HK (Cl HK) or (Cl LK), and PKa or Plm are indicated on the right. Numbers at the tops of gels represent incubation times in minutes.

Kininogen cleavage by Plm. (A) Schematic diagrams of human HK (top) and LK (bottom) showing domain structure and the disulfide bond connecting the N and C termini. The position of the BK nanopeptide is shown in black. (B-G) Coomassie Blue–stained SDS polyacrylamide gels showing HK and LK cleavage. At indicated times, samples were removed into nonreducing sample buffer and size fractionated on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. (B) Time course of HK cleavage by PKa. Human plasma–derived HK (200 nM) was incubated with PKa (2 nM) in reaction buffer at 37°C. The right panel is a western blot of samples from a reaction similar to that in panel D using an antibody to BK. (C) Time course of LK cleavage by PKa. Human plasma–derived LK (200 nM) was incubated with 2 (left) or 50 nM (right) of PKa in reaction buffer at 37°C. (D-E) Human plasma–derived HK (800 nM) incubated with 160 nM of Plm-Lys311 (D) or Plm-Glu311 (E). Bottom shows western blots for samples from reactions in the top using an antibody to BK. (F-G) Human plasma–derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 nM of Plm-Lys311 (D) or Plm-Glu311 (E). For all panels, positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left. Positions of standards for uncleaved HK or LK, cleaved forms of HK (Cl HK) or (Cl LK), and PKa or Plm are indicated on the right. Numbers at the tops of gels represent incubation times in minutes.

HK cleavage patterns produced by incubation with Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311 are shown in Figure 3D-E, respectively. Corresponding western blots (Figure 3D-E, lower) indicate BK is released by Plm-Glu311 more rapidly than by Plm-Lys311. Perhaps Plm-Glu311 makes the second cleavage after Lys362 that releases BK more efficiently than Plm-Lys311. Alternatively, Plm-Lys311 and Plm-Glu311 may cleave HK at different sites. A similar shift to that observed with PKa occurred when LK was incubated with Plm-Lys311 (Figure 3F) or Plm-Glu311 (Figure 3G). For HK and LK, additional cleavage occurred over time with Plms that were not observed with PKa, indicating PKa and Plm cleave the kininogens differently.

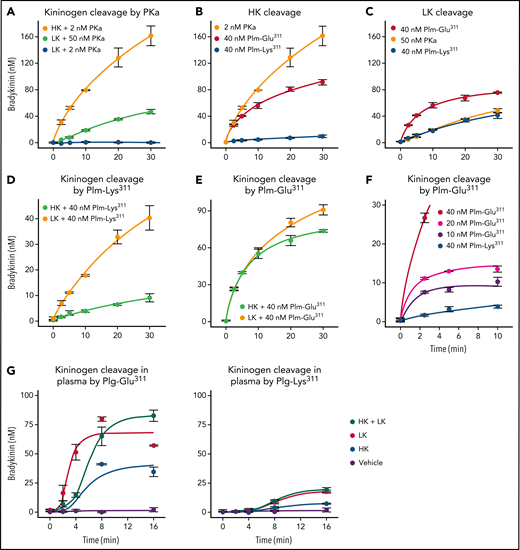

BK generation

PKa released BK from HK at a rate 50- to 100-fold higher than from LK (Figure 4A). BK release from HK catalyzed by Plm-Lys311 was at least 50-fold slower than in reactions with PKa (Figure 4B). Interestingly, PKa and Plm-Lys311 released BK from LK at similar rates (Figure 4C). Furthermore, Plm-Lys311 released BK at a rate approximately three- to fourfold higher from LK than from HK (Figure 4D). Plm-Glu311 liberated BK at an initial rate at least 10-fold faster from HK (Figure 4B) and two- to threefold faster from LK (Figure 4C) than from Plm-Lys311. Indeed, BK release catalyzed by Plm-Glu311 was comparable for HK and LK (Figure 4E). In experiments with HK, peak BK generation roughly correlated with Plm-Glu311 concentration (Figure 4F), suggesting a stochiometric interaction rather than a Michaelis-Menten–type process. When comparing these data with results shown in Figure 3, it is again apparent that kininogen cleavage on SDS polyacylamide gels does not necessarily reflect BK release, probably because Plms are cleaving kininogens at locations other than those required to release BK.

BK generation from HK and LK. For all reactions, samples were collected at the indicated time points, and BK concentration was determined by ELISA. (A) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 2 nM of PKa (orange), and plasma-derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 (light green) or 2 nM of PKa (blue). (B) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 2 nM of PKa (orange), 40 nM of Plm-Glu311 (red), or 40 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue). (C) Plasma-derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 nM of PKa (orange), 40 nM of Plm-Glu311 (red), or 40 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue). (D) Plasma-derived HK (light green) or LK (orange; 200 nM) incubated with 40 nM of Plm-Lys311. (E) Plasma-derived HK (green) or LK (orange; 200 nM) incubated with 40 nM of Plm-Glu311. (F) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 40 (red), 20 (magenta), or 10 nM (purple) of Plm-Glu311 or 40 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue). (G) Plasma from a patient deficient in HK and LK was supplemented with 600 nM of plasma-derived HK (blue), 2.3 μM of plasma-derived LK (red), HK and LK (green), or vehicle (purple). Plg-Glu311 or Plg-Lys311 was added to a final concentration of 600 nM, and tPA (125 nM) was added to activate Plg. In panels A to E, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panels F and G, error bars indicate standard errors for 2 experiments.

BK generation from HK and LK. For all reactions, samples were collected at the indicated time points, and BK concentration was determined by ELISA. (A) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 2 nM of PKa (orange), and plasma-derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 (light green) or 2 nM of PKa (blue). (B) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 2 nM of PKa (orange), 40 nM of Plm-Glu311 (red), or 40 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue). (C) Plasma-derived LK (200 nM) incubated with 50 nM of PKa (orange), 40 nM of Plm-Glu311 (red), or 40 nM of Plm-Lys311 (blue). (D) Plasma-derived HK (light green) or LK (orange; 200 nM) incubated with 40 nM of Plm-Lys311. (E) Plasma-derived HK (green) or LK (orange; 200 nM) incubated with 40 nM of Plm-Glu311. (F) Plasma-derived HK (200 nM) incubated with 40 (red), 20 (magenta), or 10 nM (purple) of Plm-Glu311 or 40 nM of Plg-Lys311 (blue). (G) Plasma from a patient deficient in HK and LK was supplemented with 600 nM of plasma-derived HK (blue), 2.3 μM of plasma-derived LK (red), HK and LK (green), or vehicle (purple). Plg-Glu311 or Plg-Lys311 was added to a final concentration of 600 nM, and tPA (125 nM) was added to activate Plg. In panels A to E, error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements. In panels F and G, error bars indicate standard errors for 2 experiments.

Plasma from a person with a congenital deficiency of HK and LK (supplemental Figure 7)38 was supplemented with physiologic concentrations of plasma-derived HK (640 nM), LK (2.3 μM), or both. Plg-Lys311 or Plg-Glu311 was added, followed by tPA to activate Plg. For Plg-Lys311 and Plg-Glu311, BK generation was greater in plasma containing LK than in plasma containing HK (Figure 4G). As shown in Figure 1E, BK generation was greater with Plg-Glu311 (Figure 4G, left) than with Plg-Lys311 (Figure 4G, right). As in Figure 2G, adding KV999272 to block PKa activity did not affect results (supplemental Figure 8).

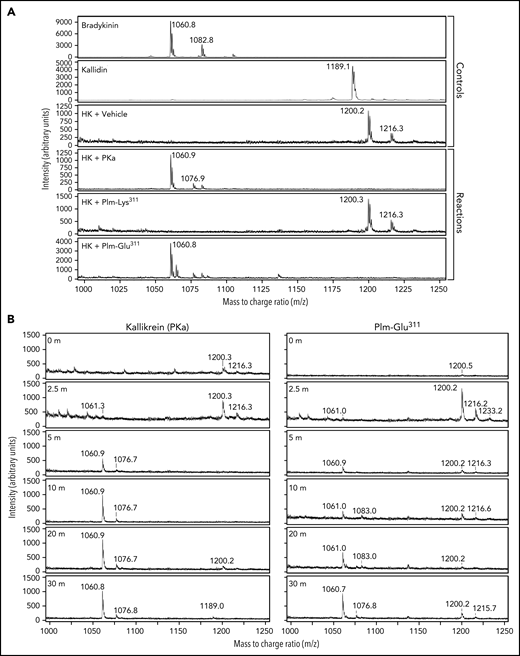

Mass spectroscopy

The ELISA used in this study does not distinguish between BK and kallidin (Lys-BK) and may detect other novel peptides containing BK sequence. We addressed this issue with mass spectroscopy. Mass spectra for BK and kallidin standards are shown in Figure 5A. Although incubating HK without a protease did not result in detectable cleavage on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, a mass peak at m/z = 1200 was observed in the MALDI analysis that did not correspond to BK or kallidin. This may reflect contamination of the HK preparation with an unknown protease. Incubating HK with PKa or Plm-Glu311 generated a peak (m/z = 1060) corresponding to BK (Figure 5A). Plm-Lys311 did not produce a detectable BK peak in these experiments. Time courses of BK formation during HK incubation with PKa or Plm-Glu311 are shown in Figure 5B. The proteases generated similar patterns over time, indicating Plm-Glu311 does not form BK from an intermediate such as kallidin. Similarly, peaks representing BK were detected during LK cleavage by PKa or Plm-Glu311, with no evidence of kallidin generation (supplemental Figure 9). These data show that Plm-Glu311, like PKa, cleaves HK and LK after Arg371 and Lys362 to form BK.

Mass spectroscopy. (A) Mass spectrometry (MALDI) analysis of cleavage of HK (200 nM) by PKa (2 nM), Plm- Lys311 (40 nM), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM), or vehicle. BK and kallidin standards were used as controls. Mass peak at m/z = 1060 confirms the release of BK from cleavage of HK by PKa and Plm-Glu311. A BK peak was not observed during incubation with Plm-Lys311. (B) Comparison of mass spectra (MALDI) of time course reactions of HK incubated with PKa or Plm-Glu311. Both reactions show accumulation of bradykinin (m/z = 1060) and absence of kallidin (m/z = 1188). The absence of a kallidin peak or other peaks suggests that BK is not formed as a mass fragmentation product during the MALDI process or an intermediate of kallidin generated during the 30-minute incubation of HK with Plm-Glu311.

Mass spectroscopy. (A) Mass spectrometry (MALDI) analysis of cleavage of HK (200 nM) by PKa (2 nM), Plm- Lys311 (40 nM), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM), or vehicle. BK and kallidin standards were used as controls. Mass peak at m/z = 1060 confirms the release of BK from cleavage of HK by PKa and Plm-Glu311. A BK peak was not observed during incubation with Plm-Lys311. (B) Comparison of mass spectra (MALDI) of time course reactions of HK incubated with PKa or Plm-Glu311. Both reactions show accumulation of bradykinin (m/z = 1060) and absence of kallidin (m/z = 1188). The absence of a kallidin peak or other peaks suggests that BK is not formed as a mass fragmentation product during the MALDI process or an intermediate of kallidin generated during the 30-minute incubation of HK with Plm-Glu311.

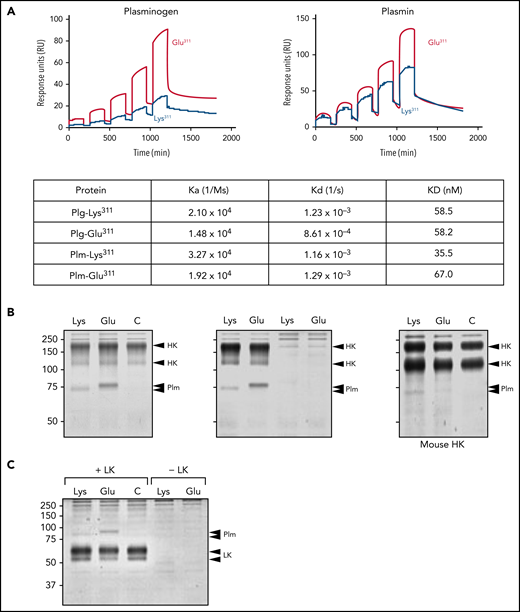

Plg binding to kininogens

We examined Plg/Plm binding to HK by surface plasmon resonance. The amounts of Plg-Glu311 and Plm-Glu311 bound to HK were greater than the amounts of Plg-Lys311 and Plm-Lys311 (Figure 6A). Plm-Glu311 also gave a stronger signal than Plm-Lys311 in coprecipitation experiments with HK (Figure 6B) and LK (Figure 6C). However, Kds for binding of Plgs and Plms containing Lys311 and Glu311 to HK determined by surface plasmon resonance were comparable (Figure 6A), indicating different affinities do not explain the enhanced BK generation associated with Plg-Glu311.

Binding of Plg and Plm to HK. (A) Surface plasmon resonance. Human HK was immobilized on CM5 sensor chips, and binding affinities for Plgs or Plms (25-400 nM) were measured by a single-cycle assay at 25°C. Binding curves for Plg-Glu311 and Plm-Glu311 are shown in red and for Plg-Lys311 and Plm-Lys311 in blue. Data were fitted with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model (dashed line). Association rate constants (ka), dissociation rate constants (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) are as listed in the table. (B) Coprecipitation. Human recombinant HK (2 μg) was incubated for 30 minutes in 500 μL of buffer with or without 2 μg of active site–inhibited Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311. HK was precipitated with anti-HA IgG bound to magnetic beads. Proteins were eluted with SDS nonreducing sample buffer and size fractionated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue (left). Similar to the left panel, except controls with Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311 but no HK were included (center). Similar to the left panel, except human HK was replaced with mouse HK (right). For all panels, positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are shown to the left of each image, and positions of controls for HK and Plms are shown to the right of each image. Human and mouse HK normally contain 2 bands. The 2 arrows for the Plm controls are needed because human and mouse Plms migrate slightly differently. (C) Coprecipitation experiment for human recombinant LK run in an identical manner to the studies for HK in panel B. Note that coprecipitated Plms migrate above LK, whereas they run lower than HK, on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Binding of Plg and Plm to HK. (A) Surface plasmon resonance. Human HK was immobilized on CM5 sensor chips, and binding affinities for Plgs or Plms (25-400 nM) were measured by a single-cycle assay at 25°C. Binding curves for Plg-Glu311 and Plm-Glu311 are shown in red and for Plg-Lys311 and Plm-Lys311 in blue. Data were fitted with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model (dashed line). Association rate constants (ka), dissociation rate constants (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) are as listed in the table. (B) Coprecipitation. Human recombinant HK (2 μg) was incubated for 30 minutes in 500 μL of buffer with or without 2 μg of active site–inhibited Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311. HK was precipitated with anti-HA IgG bound to magnetic beads. Proteins were eluted with SDS nonreducing sample buffer and size fractionated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue (left). Similar to the left panel, except controls with Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311 but no HK were included (center). Similar to the left panel, except human HK was replaced with mouse HK (right). For all panels, positions of molecular mass standards (kDa) are shown to the left of each image, and positions of controls for HK and Plms are shown to the right of each image. Human and mouse HK normally contain 2 bands. The 2 arrows for the Plm controls are needed because human and mouse Plms migrate slightly differently. (C) Coprecipitation experiment for human recombinant LK run in an identical manner to the studies for HK in panel B. Note that coprecipitated Plms migrate above LK, whereas they run lower than HK, on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Glu311 restores a consensus binding site for basic amino acids

Plg and Plm bind lysine and arginine residues on fibrin through Asp-X-Asp/Glu motifs on their kringle domains.37,39 Plg has 5 kringle domains.25,26 In human Plg, an Asp-X-Asp/Glu motif is present on kringles 1, 2, 4, and 5, but Lys311 disrupts the motif (Asp-X-Lys) in kringle 3. Interestingly, Plg-Glu311, which creates an Asp-X-Asp/Glu motif in kringle 3, is the standard in mammals (supplemental Figure 10). The Glu311 substitution in patients with HAE, therefore, restores the ancestral pattern. This raises the possibility that an interaction between Plg/Plm-Glu311 kringle 3 and basic amino acids on HK contributes to BK release. ε-ACA, a lysine analog used therapeutically to reduce fibrinolysis by inhibiting Plg binding to fibrin, inhibits BK release from HK by Plm-Lys311 and Plm-Glu311 (Figure 7A).40 Both Plms, therefore, appear to bind basic residues on HK . The additional binding site on kringle 3 provided by Glu311 may alter binding orientation to facilitate cleavage of the kininogen Arg371-Ser372 and Lys362-Arg363 bonds.

BK generation with human and mouse HK. For all studies, reactions were run in reaction buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C. BK generation was determined by ELISA. (A) Effect of ε-ACA on Plm-mediated BK generation. Human plasma–derived HK (200 nM) was incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or control vehicle (C; purple) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 10 mM of ε-ACA. (B) Human plasma–derived HK (left), human recombinant HK (rHK; center), and recombinant full-length mHK1 (right), 200 nM, were incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or C vehicle (purple). (C) Human rHK (left), recombinant full-length mHK1 (center), and mHK3 (right), 200 nM, were incubated with 40 nM of human Plm (H-Plm; mustard), mouse Plm (M-Plm; green), or vehicle C (purple). (D) Recombinant HKs used in panel C were incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or C vehicle (purple). Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements.

BK generation with human and mouse HK. For all studies, reactions were run in reaction buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C. BK generation was determined by ELISA. (A) Effect of ε-ACA on Plm-mediated BK generation. Human plasma–derived HK (200 nM) was incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or control vehicle (C; purple) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 10 mM of ε-ACA. (B) Human plasma–derived HK (left), human recombinant HK (rHK; center), and recombinant full-length mHK1 (right), 200 nM, were incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or C vehicle (purple). (C) Human rHK (left), recombinant full-length mHK1 (center), and mHK3 (right), 200 nM, were incubated with 40 nM of human Plm (H-Plm; mustard), mouse Plm (M-Plm; green), or vehicle C (purple). (D) Recombinant HKs used in panel C were incubated with PKa (2 nM; orange), Plm-Glu311 (40 nM; red), Plm-Lys311 (40 nM; blue), or C vehicle (purple). Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for duplicate experiments, each with 2 separate measurements.

Murine HK

The observation that Plg residue 311 is glutamic acid in most mammals, but is associated with HAE only in humans, is intriguing. Interestingly, little BK was released from full-length mHK1 (supplemental Figure 3) by either Plm-Lys311 or Plm-Glu311 (Figure 7B). Furthermore, BK release from human HK and mouse HK was similar when plasma-derived human Plm (Lys311) or mouse Plm (Glu311) was used to catalyze reactions (Figure 7C). These data suggest HAE requires Glu311 in the context of human Plm, in combination with features specific to human kininogens. Mice have, in addition to mHK1, an HK form (mHK3) lacking the D5 domain and part of the D6 domain found in mHK1, as a result of alternative messenger RNA splicing (supplemental Figures 3 and 4A).41 Incubating mHK3 with human or mouse Plm produced similar results to those for mHK1 (Figure 7C-D).

Discussion

The most common cause of HAE is reduced plasma C1-INH activity.1-4,15-19 As the main regulator of PKa and FXIIa, C1-INH maintains BK generation within an appropriate range. Angioedema associated with low C1-INH is highly responsive to PKa inhibitors,42-44 reduction of plasma PK,45 or a FXIIa neutralizing antibody,46 indicating dysregulated FXIIa-mediated generation of PKa is causative. Given this, the source of BK during acute episodes of angioedema in patients with low C1-INH is almost certainly HK, because LK is a poor PKa substrate. Patients with signs and symptoms of HAE, but with normal C1-INH levels, were first reported in 2000.47,48 It is estimated that this condition, called HAE with normal C1-INH, accounts for >10% of patients with HAE and perhaps substantially more.16-19 Mutations in genes for FXII,10,20,49 Plg,22,23,50,51 angiopoietin-1,52 and kininogen53 were identified in large families and are presumed causative. Suspect mutations in genes for myoferlin54 and heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase 655 have also been reported. The manifestations of HAE, therefore, may be caused by a variety of defects affecting kinin production or vascular sensitivity to kinins.

Plg-Glu311 was reported in 2018 in patients in Germany by Bork et al22 and by Dewald.23 The prevalence of the mutation is not known, but Plg-Glu311 patients have been identified in several European countries, Japan, and the United States, suggesting wide distribution.51 A relationship between fibrinolysis and kinin generation was described by Kaplan and Austen28 in 1971. Oral-lingual edema after thrombolytic therapy is a well-recognized clinical example of this association.56,57 Plm activates FXII,29,30 while PKa activates Plg and the Plg activator prourokinase.31,32,57-59 It has been proposed that Plg-Glu311 may have an enhanced capacity to activate the KKS.16 Hypothetically, if Plm-Glu311 activates FXII faster than Plm-Lys311, or if PKa activates Plg-Glu311 more rapidly than Plg-Lys311, a positive feedback cycle that amplifies PK activation could result, leading to excessive kinin production.

Our data suggest an alternative scenario in which Plg-Glu311 contributes to angioedema by directly catalyzing kinin release from HK and LK. HK is a component of the KKS, serving as a substrate for PKa and a cofactor for PK and FXI binding to surfaces during contact activation. LK lacks the elements for surface, PK, and FXI binding found on the HK D5 and D6 domains and is thought to function primarily as a substrate for tissue kallikreins.60,61 Previously, several groups reported HK cleavage by Plm, although it is not clear that BK was a major product of the reaction.31-33,62 In our analysis, both wild-type Plm-Lys311 and mutant Plm-Glu311 readily cleaved human HK and LK, but BK release was substantially greater with Plm-Glu311. Interestingly, Plm-Glu311 catalyzed BK release from HK and LK at comparable rates. Furthermore, Plm-Lys311 released BK from LK 3 to 4 times faster than from HK. Because the plasma concentration of LK is two- to fourfold greater than HK, most BK generated by either Plg-Lys311 or Plg-Glu311 may come from LK, a premise supported by our studies with supplemented kininogen-deficient plasmas.

Replacing Plg-Lys311 with glutamic acid creates a consensus binding site for lysine and arginine side chains in the kringle 3 domain, similar to those normally found on kringles 1, 2, 4, and 5.25,26 The ability of ε-ACA to inhibit HK cleavage by Plm indicates binding to basic amino acids is important for the Plm-HK interaction, as shown previously by Kleniewski et al.63,64 Lysine binding to kringle 3 may alter the orientation of kininogen-bound Plm relative to the kininogen Arg371-Ser372 and Lys362-Arg363 cleavage sites. Curiously, residue 311 is normally glutamic acid in mammalian Plgs. Lys311 is found only in humans and the closely related chimpanzee and gorilla (supplemental Figure 10). However, Glu311 is linked to HAE only in humans. Our data support the conclusion that it is the combination of Glu311 in human Plm and human kininogen that is pathogenic. HK and LK share common D1, D2, D3, and D4 domains. There are differences in distribution of basic amino acids in these domains between human and mouse kininogens that may underlie the different susceptibilities of the proteins for Plg-Glu311–catalyzed BK release (supplemental Figure 2).

There is a predilection for oral-lingual edema in Plg-Glu311 carriers.51 Tongue swelling occurs in 80% of symptomatic Plg-Glu311 patients and is often the only manifestation of HAE.16-19,22,51 Edema involving the extremities, gastrointestinal tract, and larynx is less common, and the prodromal rash (erythema marginatum) associated with HAE is rare in Plg-Glu311 patients. Observations of patients with bleeding tendencies indicate that the oral cavity has relatively high intrinsic fibrinolytic activity.65 Therefore, the predilection for oral-lingual angioedema in Plg-Glu311 patients may, at least in part, reflect normal robust Plg activation in the mouth. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which inhibit BK degradation, may also trigger oral-lingual angioedema. A recent case report by Wang et al66 describes successful treatment of a patient with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–induced angioedema with the lysine analog tranexamic acid, raising the possibility that local Plm-mediated production of BK contributes to the syndrome.

Our study raises the possibility that certain therapeutic approaches commonly used to treat patients with HAE, including C1-INH supplementation and PKa inhibition, may be less effective in Plg-Glu311 patients. In a case series, Bork et al51 reported a mean angioedema episode duration of 4.3 ± 2.6 hours (201 episodes) in 13 patients with Plg-Glu311 treated with the B2 receptor antagonist icatibant, compared with 44.7 ± 28.6 hours (149 episodes) in the same patients in the absence of treatment (88% reduction in episode duration). In 12 patients receiving C1-INH infusion (74 episodes), treatment had a more modest effect (mean episode duration decreased from 48.2 ± 32.5 to 31.5 ± 8.6 hours). These results suggest icatibant is more effective than C1-INH in Plg-Glu311–associated HAE and are consistent with a relatively small contribution to angioedema from the KKS. However, such a conclusion should be considered tentative. A majority of Plg-Glu311 carriers receiving C1-INH in this study were considered to have had good responses,51 perhaps reflecting a KKS contribution to the disease process. Alternatively, C1-INH inhibits Plm and tPA,67,68 and this could be relevant at doses used to treat angioedema. There are few data on the efficacy of PKa inhibitors in Plg-Glu311 patients. Such information will be important in determining the contributions of different BK-generating pathways that may operate in Plg-Glu311 patients. World Allergy Organization/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2021 guidelines calling for screening for known mutations in HAE patients with normal C1-INH will also help in this regard.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards HL140025 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (D.G.); APP1129592 from the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (J.C.W. and R.H.P.L.), and FL18010019 from the Australian Research Council (J.C.W. and R.H.P.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.K.D. designed and performed assays for protease activation and bradykinin generation and contributed to writing the manuscript; S.K. and D.R.P. designed and performed mass spectroscopy analysis and contributed to writing the manuscript; M.-F.S. and B.M.M. prepared recombinant high molecular weight kininogens and conducted precipitation experiments; J.C.W. and A.J.Q. prepared recombinant plasminogen and plasmin and performed surface plasmon resonance binding experiments; E.P.F. contributed to writing the manuscript; R.H.P.L. oversaw preparation of recombinant plasminogen mutants and binding studies and contributed to writing the manuscript; and D.G. oversaw the project and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.G. receives consultancy fees from pharmaceutical companies (Anthos Therapeutics, Aronora, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ionis, Janssen) with an interest in inhibition of contact activation and the kallikrein-kinin system for therapeutic purposes. E.P.F. is an employee of Kalvista Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Gailani, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Room 4918, The Vanderbilt Clinic, 1301 Medical Center Drive, Nashville, TN 37232; e-mail: dave.gailani@vanderbilt.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.