Key Points

KDM1A activation marks high-risk CLL, and genetic KDM1A depletion impedes leukemic growth via cell-intrinsic and milieu-derived programs.

KDM1A loss alters H3 methylation, promoter occupancies, and transcriptomes in CLL alongside apoptotic effects of KDM1A pharmacoinhibition.

Abstract

In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), epigenetic alterations are considered to centrally shape the transcriptional signatures that drive disease evolution and underlie its biological and clinical subsets. Characterizations of epigenetic regulators, particularly histone-modifying enzymes, are very rudimentary in CLL. In efforts to establish effectors of the CLL-associated oncogene T-cell leukemia 1A (TCL1A), we identified here the lysine-specific histone demethylase KDM1A to interact with the TCL1A protein in B cells in conjunction with an increased catalytic activity of KDM1A. We demonstrate that KDM1A is upregulated in malignant B cells. Elevated KDM1A and associated gene expression signatures correlated with aggressive disease features and adverse clinical outcomes in a large prospective CLL trial cohort. Genetic Kdm1a knockdown in Eμ-TCL1A mice reduced leukemic burden and prolonged animal survival, accompanied by upregulated p53 and proapoptotic pathways. Genetic KDM1A depletion also affected milieu components (T, stromal, and monocytic cells), resulting in significant reductions in their capacity to support CLL-cell survival and proliferation. Integrated analyses of differential global transcriptomes (RNA sequencing) and H3K4me3 marks (chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing) in Eμ-TCL1A vs iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (confirmed in human CLL) implicate KDM1A as an oncogenic transcriptional repressor in CLL which alters histone methylation patterns with pronounced effects on defined cell death and motility pathways. Finally, pharmacologic KDM1A inhibition altered H3K4/9 target methylation and revealed marked anti–B-cell leukemic synergisms. Overall, we established the pathogenic role and effector networks of KDM1A in CLL via tumor-cell intrinsic mechanisms and its impacts in cells of the microenvironment. Our data also provide rationales to further investigate therapeutic KDM1A targeting in CLL.

Introduction

The concept of cancer as a genetic disease has been supplemented by mounting evidence that also epigenetic alterations, including permissive chromatin states, significantly confer the malignant cell fate changes.1 In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the described patterns of locally disordered DNA methylation or their global changes, as well as alterations in the chromatin landscape, can only be in part attributed to underlying genetic variants of epigenetic regulators.2-5 Nevertheless, epigenetic evolution in CLL, as dictated by inherent cell-of-origin and general leukemogenic programs, is considered a major determinant of the variable transcriptional signatures that underlie the different clinically relevant biological features of the disease.2 In fact, DNA methylome analyses allowed the assignment of CLL cases to differentiate epigenetic subgroups that correlate well with major histogenetic trajectories, ie, memory vs naïve B-cell derivation.4,6,7 These differential methylome patterns also associate well with the major immunogenetic strata of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene mutated (M-CLL) vs unmutated (U-CLL) cases.

Aberrant high expression of the T-cell leukemia / lymphoma 1A (TCL1A) oncogene is centrally implicated in the pathogenesis of CLL. Higher TCL1A levels are more frequent in U-CLL and linked to adverse features, such as high-risk (cyto)genetics, faster tumor cell doubling, and poorer responses to chemoimmunotherapies.8,9 Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable promoter/Eμ-enhancer TCL1A-transgenic (Eμ-TCL1A-tg) mice resemble the biology and course of U-CLL, including recapitulation of involved methylome changes.10,11 In the evolving molecular concept of the 14 kDa TCL1A adapter protein,12,13 it was also shown to interact with the DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), which reduces its enzymatic activity and contributes to epigenetic reprogramming in CLL.14 Fittingly, induced mono- or biallelic losses of Dnmt3a result in murine CLL.15

Beyond that, epigenetic regulators in general and histone-modifying enzymes (HME) in particular are much less well-investigated in CLL. However, histone modifications are key alterations in the pathogenesis of various cancer types, including CLL.16-19 Deregulated histone methylation has been shown to promote oncogene expression, tumor suppressor inactivation, deficient DNA repair, and chromosomal instability.20 The lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A (KDM1A, also LSD1) removes methyl groups from mono- or dimethylated lysine 4 or 9 on histone 3 (H3K4me1/2; H3K9me1/2) working as a repressor or activator of gene expression, respectively.21 This dual effect also depends on further specific lysines and histones that can be targeted through KDM1A (ie, H3K27, H4K20). Its association with transcriptionally repressing (eg, CoREST, SNAIL) or coactivating (eg, estrogen or androgen receptor) chromatin complexes is functionally best established.22,23 Moreover, KDM1A was shown to demethylate specific lysine residues of nonhistone proteins (eg, P53, STAT3, E2F1) or to possess methylase-independent functions.22,23

Upregulated KDM1A has been linked to poor clinical outcomes in various cancers, including hematological malignancies.24 KDM1A is involved in cancer stem cell self-renewal, cell proliferation and differentiation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition as well as in metastasis.22 Numerous KDM1A-targeting compounds have been developed and some are undergoing clinical investigation, particularly for small-cell lung cancer and acute myeloid leukemia.25

We demonstrate here that TCL1A interacts with KDM1A and enhances its demethylase activity in B cells. Moreover, a KDM1Ahigh gene expression signature marked more aggressive CLL. In leukemic Eμ-TCL1A mice, knockdown of Kdm1a resulted in reduced tumor burden and prolonged animal survival. As underlying, reduced CLL-intrinsic Kdm1a impeded tumor cell growth, and depleted Kdm1a in the micromilieu reduced its prosurvival support. The altered patterns of histone methylation and gene expression in leukemic cells upon Kdm1a knockdown implicate a transcriptional repressor function. Pharmacologic KDM1A inhibition increased histone methylation and induced CLL-cell apoptosis. These data establish the pathogenetic relevance and target properties of KDM1A in CLL.

Methods

Patient samples

Peripheral blood (PB) samples from patients with CLL (departmental biorepository) and age-matched healthy donors (institutional blood bank) were obtained under Intitutional Review Board–approved protocols (#11-319, 01-143, 19-1085) with written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ficoll-isolated PB mononuclear cells (MCs) and purified B cells were cultured as reported.26 Patient data are summarized in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website.

Animal experiments

Procedures were approved under NRW State Governmental #’s 84-02.04.2014.A146, 2019.A009, and 2016.A243. Doxycycline (Dox) inducible Kdm1a knockdown (iKdm1aKD) mice were provided by Roland Schüle (University of Freiburg).27iKdm1aKD and Eμ-TCL1A mice were crossbred to obtain iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A animals. Kdm1a knockdown in murine CLL was achieved via a Dox-containing diet. Details are given in supplemental Materials.

Flow cytometry

Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and reagents are listed in supplemental Table 2. β-Galactosidase substrate fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside staining was conducted to assess cellular senescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher). Flow-cytometric (Gallios device) analysis used the Kaluza software (both Beckman Coulter).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting (cell protein lysates) was conducted as described.8 Antibodies and working dilutions are listed in supplemental Table 3. Blot development used WesternBright ECL (Advansta). Visualization on autoradiography films (Santa Cruz) was followed by densitometry using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Immunoprecipitation

Anti-TCL1A antibody coupled Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen) were incubated with cell lysates at 4°C overnight to pull down TCL1A with interacting proteins. Eluates of immunoprecipitates and input cell extracts (controls) were analyzed using immunoblotting.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq)

The SimpleChIP enzymatic chromatin IP Kit (cell signaling) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After reverse cross-linking and DNA purification, ChIP-DNA and whole nuclear DNA (control) were subjected to library preparation and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 device. Further details on data processing are provided in supplemental Materials.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA, isolated from murine splenocytes using the mirVana Kit (Invitrogen), was subjected to library preparation and sequenced (Illumina NovaSeq6000; result of data analyses is provided in supplemental Materials).

Gene expression profiling (GEP)

Tissue cytometry

Immunofluorescent staining was performed on 6 μm cryosections of murine spleens (details are provided in supplemental Materials). Primary and secondary antibodies (supplemental Table 4) were applied according to standard procedures. Visual slides were computed and analyzed using the image cytometry software StrataQuest (TissueGnostics).

Statistics

Specific tests to assess difference probabilities (GraphPad Prism 8 and 9) are given in “Results” and the figures; P < .05 was considered significant.

Additional technical details (eg, mass spectrometry [MS] protocols) are provided in supplemental Materials.

Results

TCL1A interacts with KDM1A and enhances its activity in B cells

To study the TCL1A interactome in more detail, a quantitative large-scale MS analysis was performed on eluates of TCL1A-IPs from whole-cell lysates of CLL samples (N = 11) from genetically and clinically defined patient subgroups (supplemental Table 1) and non-malignant tonsillar B cells (N = 3).31 We identified ∼1000 proteins with significant (fold-change [FCh] > 2; false discovery rate [FDR], q < 0.05) interaction with TCL1A in isolates from tonsils and/or CLL, also confirming described binding partners, such as ATM or IκB (supplemental Table 5).32,33

Notably, in support of a (less well-established) role of nuclear TCL1A, we also detected interactions of TCL1A with chromatin-modifying enzymes (supplemental Table 6), indicating involvement of TCL1A in epigenetic transcriptional regulation. We focused on the histone demethylase, KDM1A, based on its established importance in other cancers24 and a trend of differential complexation with TCL1A between M-CLL and U-CLL (Figure 1A-B). We validated the TCL1A-KDM1A interaction under relevant conditions (eg, proliferation and DNA damage) in human CLL cells and in TCL1A-tg B cells of Eμ-TCL1A mice (Figure 1C-D). Importantly, we observed an increased histone demethylase activity after introduction of TCL1A into DoHH2 B-cell lymphoma cells (P = .008, Figure 1E). In line with this, a quantitative MS-based analysis of histone posttranslational modifications demonstrated lower H3K9me2/3 in DoHH2TCL1A cells than in controls (Figure 1F). We confirmed lower levels of H3K9me3 in these DoHH2TCL1A cells using immunoblotting (Figure 1G). Higher KDM1A levels also correlated with higher demethylase activity in human CLL cells (Figure 1H). A less abundant physical TCL1A-KDM1A interaction was identified in T-PLL cells (Figure 1I).

TCL1A interacts with KDM1A and enhances its demethylase activity. (A) Experimental setting of MS of TCL1A coimmunoprecipitations (co-IPs) in human CLL B cells (nonmalignant B cells from tonsils as biological controls). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) co-IPs in CLL B cells served as technical controls. CLL sample strata: immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) mutated (M-CLL, N = 6) vs IGHV unmutated (U-CLL, N = 5). Proteins that showed a significant enrichment between the IgG control and CLL samples (459 proteins) or tonsils (889 proteins) were considered TCL1A interacting partners (Welch test, FDR q-value ≤ 0.05, FCh ≥ 2.0). Four hundred nine and 407 TCL1A-interacting proteins were identified in M-CLL and U-CLL cells, respectively (324 proteins overlapped between both subsets). (B) Left: selected pathways identified by overrepresentation analysis (ORA; supplemental Table 6), bars illustrate the percentage of involved proteins from the TCL1A interactome within each pathway. Right: heatmap of chromatin-modifying enzymes that interact with TCL1A protein. KDM1A (∗) tended to interact with TCL1A at a higher abundance in U-CLL than M-CLL (P = .052, Mann Whitney test). (C) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies in primary CLL B cells cocultured with differentiated THP-1 monocytic cells supplemented with CpG and IL-15 for 36 hours to induce proliferation (Ki67+ 38.9%-54.1%). Each lane represents an individual CLL sample. (D) Immunoblots of TCL1A co-IPs from Eμ-TCL1A splenic leukemic cells (2 mice) treated with DNA double strand break–inducing etoposide (10 μM, at 0, 1, and 3 hours). (E) Histone demethylase activity assay: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in DoHH2 B cells transfected with TCL1A (N = 3, each experiment in duplicates; P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (F) Quantitative MS analysis of histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in DoHH2±TCL1A B cells (N = 3 independent experiments). Left: principal component analysis (PCA) of MS data showing distinct groups by the presence of TCL1A (blue DoHH2, red DoHH2TCL1A). Each data point represents 1 independent experiment. Middle: heatmap showing differential histone single marks in TCL1A positive and negative DoHH2 cells. Right: lower levels of H3K9me2 (P = .013) and H3K9me3 (P < .001) in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells (Student t test, mean ± SEM). (G) Immunoblots showing lower levels of H3K9me3 in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells. (H) Top: immunoblots showing KDM1A levels in 14 CLL (lanes = case numbers). Bottom: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in cases with higher KDM1A levels as per KDM1A activity assay (N = 4 CLL per group, P = .028, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM; KDM1A levels shown in top panel). Supplemental Figure 1A shows no correlation between KDM1A and H3K9me2/3 protein signals (nonexclusive impact of KDM1A on H3K9me2/3 levels). (I) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies illustrating higher abundance of TCL1A-KDM1A interaction in primary CLL B cells vs T-PLL T cells. Each lane represents an individual B-CLL or T-PLL sample. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

TCL1A interacts with KDM1A and enhances its demethylase activity. (A) Experimental setting of MS of TCL1A coimmunoprecipitations (co-IPs) in human CLL B cells (nonmalignant B cells from tonsils as biological controls). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) co-IPs in CLL B cells served as technical controls. CLL sample strata: immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) mutated (M-CLL, N = 6) vs IGHV unmutated (U-CLL, N = 5). Proteins that showed a significant enrichment between the IgG control and CLL samples (459 proteins) or tonsils (889 proteins) were considered TCL1A interacting partners (Welch test, FDR q-value ≤ 0.05, FCh ≥ 2.0). Four hundred nine and 407 TCL1A-interacting proteins were identified in M-CLL and U-CLL cells, respectively (324 proteins overlapped between both subsets). (B) Left: selected pathways identified by overrepresentation analysis (ORA; supplemental Table 6), bars illustrate the percentage of involved proteins from the TCL1A interactome within each pathway. Right: heatmap of chromatin-modifying enzymes that interact with TCL1A protein. KDM1A (∗) tended to interact with TCL1A at a higher abundance in U-CLL than M-CLL (P = .052, Mann Whitney test). (C) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies in primary CLL B cells cocultured with differentiated THP-1 monocytic cells supplemented with CpG and IL-15 for 36 hours to induce proliferation (Ki67+ 38.9%-54.1%). Each lane represents an individual CLL sample. (D) Immunoblots of TCL1A co-IPs from Eμ-TCL1A splenic leukemic cells (2 mice) treated with DNA double strand break–inducing etoposide (10 μM, at 0, 1, and 3 hours). (E) Histone demethylase activity assay: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in DoHH2 B cells transfected with TCL1A (N = 3, each experiment in duplicates; P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (F) Quantitative MS analysis of histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in DoHH2±TCL1A B cells (N = 3 independent experiments). Left: principal component analysis (PCA) of MS data showing distinct groups by the presence of TCL1A (blue DoHH2, red DoHH2TCL1A). Each data point represents 1 independent experiment. Middle: heatmap showing differential histone single marks in TCL1A positive and negative DoHH2 cells. Right: lower levels of H3K9me2 (P = .013) and H3K9me3 (P < .001) in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells (Student t test, mean ± SEM). (G) Immunoblots showing lower levels of H3K9me3 in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells. (H) Top: immunoblots showing KDM1A levels in 14 CLL (lanes = case numbers). Bottom: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in cases with higher KDM1A levels as per KDM1A activity assay (N = 4 CLL per group, P = .028, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM; KDM1A levels shown in top panel). Supplemental Figure 1A shows no correlation between KDM1A and H3K9me2/3 protein signals (nonexclusive impact of KDM1A on H3K9me2/3 levels). (I) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies illustrating higher abundance of TCL1A-KDM1A interaction in primary CLL B cells vs T-PLL T cells. Each lane represents an individual B-CLL or T-PLL sample. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

Together, these results suggest that increased TCL1A levels in CLL might affect the epigenetic signature of B cells by directly modulating the demethylase activity of KDM1A.

Higher KDM1A levels are associated with adverse features in CLL

Apart from this novel interaction of TCL1A with KDM1A, there have been no dedicated reports on KDM1A in CLL. We, therefore, analyzed available genomic data on large CLL series and identified that KDM1A is not a recurrent target of copy number alterations or mutations (copy number alterations: N = 319 CLL30,34; mutations: N = 1308 CLL, eBioPortal35-38). Analysis of KDM1A messanger RNA (mRNA) expression in CLL using public databases39 revealed its upregulation at magnitudes similar to other leukemias (supplemental Figure 1B).

Immunoblotting detected increased KDM1A protein levels in primary CLL cells than healthy B cells (P = .004, Figure 2A). Higher KDM1A mRNA levels were observed in CLL cases at disease progression (P = .037, Figure 2B) as well as in Eμ-TCL1A mice at overt leukemic vs preleukemic stages (P = .04, supplemental Figure 1C). Furthermore, we analyzed GEP data of samples from patients (N = 337) enrolled in the CLL8 trial. This prospective study compared outcomes after fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide treatment with or without rituximab (FC vs FCR).30 We identified 586 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among patients of the low vs high quartile of KDM1A expression (supplemental Table 7). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways highlighted DNA replication, DNA repair, and B-cell receptor signaling in the KDM1Ahigh quartile, whereas cytokine receptor pathways were enriched in the KDM1Alow quartile (Figure 2C-D). Three clusters (1, 2, 3; FCh > 1.55; FDR q < 0.02) were identified using the top 449 DEGs (Figure 2E; supplemental Table 8). KDM1A levels were significantly higher in cluster 3 than in cluster 1 (P < .001, supplemental Figure 1D). SLAMF6, whose gene product has been implicated in CLL progression,40 positively correlated with KDM1A levels. In contrast, the AP1 transcription factor (TF) subunits FOS and FOSB showed lower expression in patients with high KDM1A (supplemental Figure 1E). TCL1A expression was significantly high in the cases of KDM1Ahigh quartile (supplemental Figure 1F).

There were higher white blood cell counts (P < .001) and higher serum thymidine kinase levels (P = .009) at presentation in patients in cluster 3 (Figure 2F-G). Higher TCL1A levels (P < .001), higher rates of TP53 aberrations (P = .022), and shorter telomere lengths (P = .003) were also detected in this KDM1Ahigh cluster 3 (Figure 2H-J). Patients in cluster 3 (both treatment arms) had significantly shorter progression-free survival as compared with those in cluster 1 (median 32.4 months [cluster 3] vs 46.6 months [cluster 1], P = .011, Figure 2K). This prognostic impact derived predominantly from patients of the FC arm (median progression-free survival 29.1 months [cluster 3] vs 34.1 months [cluster 1], P = .029, Figure 2L; FCR: 42.4 months vs 55.2 months, P = .16; supplemental Figure 1G; confirmation in FCR300 trial41 [supplemental Figure 1H]). Most of these associations sustained in the U-CLL subset (supplemental Figure 1I-M). In summary, KDM1A is upregulated in CLL and gene expression signatures associated with higher KDM1A levels mark a more aggressive disease with adverse clinical outcomes.

Knockdown of Kdm1a reduces tumor burden in CLL mice

To evaluate the relevance of KDM1A and the therapeutic potential of its inhibition in vivo, we took advantage of the Eμ-TCL1A model and crossed it with iKdm1aKD mice (supplemental Figure 2A).27 We confirmed the systemic Dox-induced Kdm1a knockdown (Kdm1a-KD) in PB leukocytes, splenic MCs, and bone marrow (BM) leukocytes (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 2B-C). Strikingly, Dox-exposed leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice showed a significantly longer overall survival as compared with Eμ-TCL1A animals or to non-Dox–treated iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (median 67 vs 39 [P = .018] vs 41 days [P = .036], Figure 3B). In addition, white blood cell counts of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice remained relatively stable, whereas Eμ-TCL1A mice showed steadily increasing white blood cell and died from leukemia within 8 weeks (P = .01, Figure 3C). Timelines of Dox-induced Kdm1a-KD also revealed decreased numbers of CD19+CD5+ leukemic cells in PB of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (P = .013, Figure 3D). PB platelet counts dropped in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice confirming previous observations in iKdm1aKD mice,27 whereas there were no significant differences in erythroid PB parameters upon Dox-exposure between Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A leukemic mice (supplemental Figure 2D-E).

Knockdown of Kdm1a reduces leukemic burden in vivo. (A) Setup of mouse experiments. Top: for survival analyses, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼50 to 70 × 109/L) were treated with Dox to induce Kdm1a-KD and observed until the clinical endpoints (defined in supplemental Materials). Blood was taken every week to monitor leukemic load and changes in other blood parameters. Bottom: for RNA-seq and cryosectioning, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼30 × 109/L) were exposed to Dox for 2 weeks. For ChIP experiments, mice were treated with Dox for 2 weeks when WBCs reached 80 to 100 × 109/L. (B) Significantly longer survival (Log-rank test) of Dox-treated leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red, 12 females, median 67 days) vs Dox-exposed leukemic Eμ-TCL1A mice (blue, 12 females, median 39 days, P = .018) or vs non-Dox–exposed leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (green, 9 females, median 41 days, P = .036). (C) Significantly lower WBCs in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (N = 8, red) leukemic mice under Dox treatment as compared with Eμ-TCL1A (N = 7, blue, P = .01, 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (D) Lower total number of PB leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells (flow cytometry) in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 6, red) in comparison with those of Eμ-TCL1A (N = 6, blue, P = .013, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). End: end point of survival experiment. (E) Lower percentage of CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens and BM of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice under short term (≤2 weeks, left) or long term (≥4 weeks, right) in vivo Dox treatment (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). (F) Top: representative images (taken at 60× original magnification) of immunofluorescent B220/KDM1A/Hoechst staining of spleen sections from Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice under Dox treatment for 2 weeks (B220 green, KDM1A red, Hoechst blue). Bottom: quantification of B220/KDM1A signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest showing reduced population of KDM1A+ cells (left, P < .001), B220+ B cells (middle, P = .002), and KDM1A+B220+ cells (right, P = .009) in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) than that of Eμ-TCL1A (blue) mice (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (G) Spleen volumetry after magnetic resonance imaging scanning of Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice (WBCs ∼50 × 109/L) treated with Dox for 6 weeks. Representative images of abdominal region (red dashed line highlights splenic circumference). Bar chart displays splenic volumes before and under Dox treatment at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Both groups presented significantly enlarged spleens at 6 weeks (N = 5, P < .05, Student t test, mean ± SEM). (H) Tissue cytometer analysis of B220/Ki-67 immunofluorescent signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest. Left: representative tissue cytometry plots show B220+/Ki-67+ B cells in spleens (Eμ-TCL1A blue, iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A red). Right: quantified signal implicates decreased Ki-67+ B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A animals (N = 4 of each group, P = .029, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (I) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic leukemic B cells in spleens (annexin V staining). Left: representative density plots and histograms illustrate a smaller population of leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells and a higher percentage of apoptotic leukemic cells in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice after 2 weeks of Dox treatment (comparison to Eμ-TCL1A). Right: higher percentages of apoptotic CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A compared with that of Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 5 of each group, P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). BMMCs, bone marrow MCs.

Knockdown of Kdm1a reduces leukemic burden in vivo. (A) Setup of mouse experiments. Top: for survival analyses, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼50 to 70 × 109/L) were treated with Dox to induce Kdm1a-KD and observed until the clinical endpoints (defined in supplemental Materials). Blood was taken every week to monitor leukemic load and changes in other blood parameters. Bottom: for RNA-seq and cryosectioning, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼30 × 109/L) were exposed to Dox for 2 weeks. For ChIP experiments, mice were treated with Dox for 2 weeks when WBCs reached 80 to 100 × 109/L. (B) Significantly longer survival (Log-rank test) of Dox-treated leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red, 12 females, median 67 days) vs Dox-exposed leukemic Eμ-TCL1A mice (blue, 12 females, median 39 days, P = .018) or vs non-Dox–exposed leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (green, 9 females, median 41 days, P = .036). (C) Significantly lower WBCs in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (N = 8, red) leukemic mice under Dox treatment as compared with Eμ-TCL1A (N = 7, blue, P = .01, 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (D) Lower total number of PB leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells (flow cytometry) in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 6, red) in comparison with those of Eμ-TCL1A (N = 6, blue, P = .013, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). End: end point of survival experiment. (E) Lower percentage of CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens and BM of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice under short term (≤2 weeks, left) or long term (≥4 weeks, right) in vivo Dox treatment (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). (F) Top: representative images (taken at 60× original magnification) of immunofluorescent B220/KDM1A/Hoechst staining of spleen sections from Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice under Dox treatment for 2 weeks (B220 green, KDM1A red, Hoechst blue). Bottom: quantification of B220/KDM1A signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest showing reduced population of KDM1A+ cells (left, P < .001), B220+ B cells (middle, P = .002), and KDM1A+B220+ cells (right, P = .009) in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) than that of Eμ-TCL1A (blue) mice (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (G) Spleen volumetry after magnetic resonance imaging scanning of Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice (WBCs ∼50 × 109/L) treated with Dox for 6 weeks. Representative images of abdominal region (red dashed line highlights splenic circumference). Bar chart displays splenic volumes before and under Dox treatment at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Both groups presented significantly enlarged spleens at 6 weeks (N = 5, P < .05, Student t test, mean ± SEM). (H) Tissue cytometer analysis of B220/Ki-67 immunofluorescent signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest. Left: representative tissue cytometry plots show B220+/Ki-67+ B cells in spleens (Eμ-TCL1A blue, iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A red). Right: quantified signal implicates decreased Ki-67+ B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A animals (N = 4 of each group, P = .029, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (I) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic leukemic B cells in spleens (annexin V staining). Left: representative density plots and histograms illustrate a smaller population of leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells and a higher percentage of apoptotic leukemic cells in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice after 2 weeks of Dox treatment (comparison to Eμ-TCL1A). Right: higher percentages of apoptotic CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A compared with that of Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 5 of each group, P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). BMMCs, bone marrow MCs.

Dox-exposed iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice showed a significant reduction in CLL-cell content of suspended spleens and BM as compared with that of Eμ-TCL1A animals (Figure 3E). Quantifications of B220/KDM1A immunofluorescence costainings of tissue sections validated the splenic B-cell depletion (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 2F). The similar extent of splenomegaly in both models (Figure 3G) might be explained by splenic stress erythropoiesis in iKdm1aKD mice as reported before.27 In fact, the Kdm1a-KD reduced the number of proliferating splenic B cells (Ki-67) and increased the population of apoptotic (AnnV) splenic CLL cells (Figure 3H-I; supplemental Figure 2G).

Collectively, genetic Kdm1a depletion in Eμ-TCL1A mice reduced tumor burden in PB, spleen, and BM via leukemic cell death, which translated into increased animal survival.

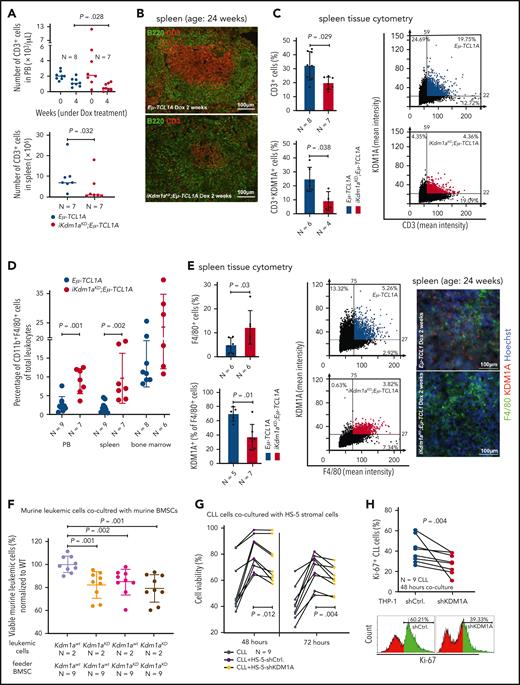

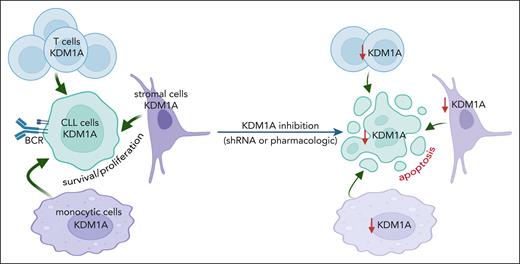

Targeting KDM1A in micromilieu components impairs survival support for CLL cells

CLL-cell sustenance and leukemic progression are entertained through vital interactions with elements of the microenvironment, eg, T cells,42 macrophages,43 or stromal cells.42 Our animal model of systemic Kdm1a-KD allows to address the role of KDM1A in non-CLL cells and to draw parallels with whole-organismal effects of its pharmacologic targeting. CD3+ T-cell numbers were reduced in PB (4 weeks Dox-exposure, P = .028) and spleens (at end point, P = .032) of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice vs Eμ-TCL1A animals (Figure 4A). Immunostained sections showed lower T-cell numbers in splenic germinal centers in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A animals (Figure 4B-C) accompanied by reversion of the skewed CD4+/8+ ratio in Eμ-TCL1A mice (supplemental Figure 3A). Importantly, pharmacoinhibition of KDM1A did not affect T-cell counts in wild-type mice or in patients (NCT03136185 trial data of IMG7289 in myelodysplastic syndrome) (supplemental Figure 3B-C). In addition, an increased percentage of CD11b+F4/80+ monocytes or macrophages was present in PB and spleens of Dox-exposed iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (Figure 4D-E). There were no significant differences in splenic vimentin-positive fibroblast counts between both models, despite decreased Kdm1a protein levels in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A fibroblasts (supplemental Figure 3D).

Effect of Kdm1a depletion on components of the CLL microenvironment. (A) iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A leukemic mice (red) with reduced absolute numbers of CD3+ T cells in PB (top, Dox-treatment for 4 weeks, P = .028) and spleen (bottom, Dox-treatment until end of survival experiment, P = .032) compared with those of Eμ-TCL1A animals (blue, Mann Whitney test). “N” in panels A-E indicates the number of analyzed animals. (B) Representative images of B220 (green)/CD3 (red) immunofluorescence stainings illustrating reduced density of CD3+ T cells in splenic germinal centers of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (bottom) vs Eμ-TCL1A (top) mice (2 weeks of Dox-treatment). (C) Tissue cytometer analysis (StrataQuest) of CD3/KDM1A immunofluorescence stainings of spleen sections. Left: quantification of CD3/KDM1A signals demonstrating decreased CD3+ T cells (P = .029) and confirming KDM1A knockdown in the reduced T cells (P = .038) in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) vs Eμ-TCL1A mice (blue, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). Right: representative tissue cytometry plots of CD3/KDM1A stainings. (D) Significantly higher percentage of CD11b+F4/80+ monocytes/macrophages in PB (P = .001) and spleens (P = .002) of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) mice vs control (blue) animals (flow cytometry, Mann Whitney test at end point). (E) Left: quantification of immunofluorescence signals from F4/80 and KDM1A costained spleen sections display an increase of F4/80+ macrophages (P = .03) with reduced KDM1A signal in F4/80+ macrophages (P = .01) in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) vs Eμ-TCL1A (blue, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD) mice after 2 weeks of Dox-treatment. Middle: representative tissue cytometry plots of F4/80 and KDM1A costainings. Right: representative immunofluorescence staining of F4/80 (green)/KDM1A (red) in spleen sections from Eμ-TCL1A (top) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (bottom) mice. (F) Murine primary CLL cells (Eμ-TCL1A with or without induced KDM1A-KD) were cocultured for 48 hours with murine BM stromal cells (BMSCs) supplemented with CpG and IL-15. Flow cytometry for annexin V demonstrates lower viabilities of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs or with iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs and of Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs (all compared with Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs; all P < .05, Mann Whitney test). (G) Human primary CLL cells as suspension cultures or cocultured with HS-5-shCtrl. or HS-5-shKDM1A stromal cells (confirmed KDM1A-KD in supplemental Figure 3E). Reduced prosurvival effect of HS-5-shKDM1A stromal feeders on CLL cells (annexin V flow cytometry) at 48 hours (P = .012) and 72 hours (P = .004; Student t test, black connecting lines for samples from identical patients). (H) Primary CLL cells cocultured for 48 hours with differentiated THP-1-shCtrl. or THP-1-shKDM1A monocytic cells (confirmed KDM1A-KD in supplemental Figure 3F) supplemented with CpG and IL-15. Top: knockdown of KDM1A in THP-1 cells reduces the percentage of proliferating (Ki-67+) CLL cells (P = .004, Student t test; black connecting lines for samples of identical patients). Bottom: representative histogram of flow-cytometric Ki-67 expression.

Effect of Kdm1a depletion on components of the CLL microenvironment. (A) iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A leukemic mice (red) with reduced absolute numbers of CD3+ T cells in PB (top, Dox-treatment for 4 weeks, P = .028) and spleen (bottom, Dox-treatment until end of survival experiment, P = .032) compared with those of Eμ-TCL1A animals (blue, Mann Whitney test). “N” in panels A-E indicates the number of analyzed animals. (B) Representative images of B220 (green)/CD3 (red) immunofluorescence stainings illustrating reduced density of CD3+ T cells in splenic germinal centers of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (bottom) vs Eμ-TCL1A (top) mice (2 weeks of Dox-treatment). (C) Tissue cytometer analysis (StrataQuest) of CD3/KDM1A immunofluorescence stainings of spleen sections. Left: quantification of CD3/KDM1A signals demonstrating decreased CD3+ T cells (P = .029) and confirming KDM1A knockdown in the reduced T cells (P = .038) in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) vs Eμ-TCL1A mice (blue, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). Right: representative tissue cytometry plots of CD3/KDM1A stainings. (D) Significantly higher percentage of CD11b+F4/80+ monocytes/macrophages in PB (P = .001) and spleens (P = .002) of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) mice vs control (blue) animals (flow cytometry, Mann Whitney test at end point). (E) Left: quantification of immunofluorescence signals from F4/80 and KDM1A costained spleen sections display an increase of F4/80+ macrophages (P = .03) with reduced KDM1A signal in F4/80+ macrophages (P = .01) in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) vs Eμ-TCL1A (blue, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD) mice after 2 weeks of Dox-treatment. Middle: representative tissue cytometry plots of F4/80 and KDM1A costainings. Right: representative immunofluorescence staining of F4/80 (green)/KDM1A (red) in spleen sections from Eμ-TCL1A (top) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (bottom) mice. (F) Murine primary CLL cells (Eμ-TCL1A with or without induced KDM1A-KD) were cocultured for 48 hours with murine BM stromal cells (BMSCs) supplemented with CpG and IL-15. Flow cytometry for annexin V demonstrates lower viabilities of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs or with iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs and of Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs (all compared with Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with Eμ-TCL1A BMSCs; all P < .05, Mann Whitney test). (G) Human primary CLL cells as suspension cultures or cocultured with HS-5-shCtrl. or HS-5-shKDM1A stromal cells (confirmed KDM1A-KD in supplemental Figure 3E). Reduced prosurvival effect of HS-5-shKDM1A stromal feeders on CLL cells (annexin V flow cytometry) at 48 hours (P = .012) and 72 hours (P = .004; Student t test, black connecting lines for samples from identical patients). (H) Primary CLL cells cocultured for 48 hours with differentiated THP-1-shCtrl. or THP-1-shKDM1A monocytic cells (confirmed KDM1A-KD in supplemental Figure 3F) supplemented with CpG and IL-15. Top: knockdown of KDM1A in THP-1 cells reduces the percentage of proliferating (Ki-67+) CLL cells (P = .004, Student t test; black connecting lines for samples of identical patients). Bottom: representative histogram of flow-cytometric Ki-67 expression.

To corroborate the conclusion of the antileukemic impact of a Kdm1a-KD to originate from combined effects on leukemic cells and milieu components, we used reciprocal coculture systems. We observed a decreased viability of primary murine CLL cells upon Kdm1a-KD (a) in cocultured murine BM stromal cells, (b) in the leukemic cells, or (c) in both compartments as compared with Eμ-TCL1A leukemic cells cocultured with Kdm1a wild-type (Kdm1aWT) murine BM stromal cells (Figure 4F). Moreover, an efficient knockdown of KDM1A in human HS-5 fibroblastic cells or in THP-1 monocytic cells (supplemental Figure 3E-F) diminished their prosurvival or proproliferative impact on cocultured human CLL cells (Figure 4G-H). Interestingly, this KDM1A-KD did not affect HS-5 stromal cell proliferation (supplemental Figure 3G), however it compromised the proliferation of THP-1 monocytes (supplemental Figure 3H).

Taken together, these findings suggest a proleukemic relevance of KDM1A in CLL via its effects in supporting cells of the micromilieu in addition to tumor-cell intrinsic mechanisms.

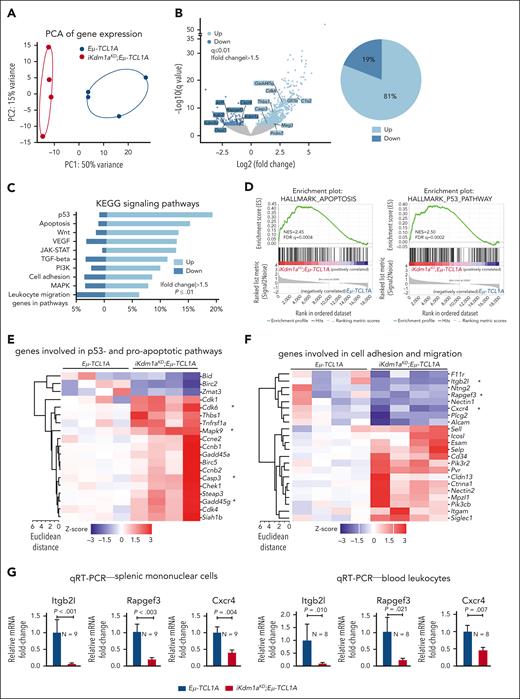

Depletion of Kdm1a in murine CLL implicates its role as a transcriptional repressor

To assess alterations in gene expression caused by the Kdm1a-KD, we performed RNA-seq of splenic MCs (mean purity 70% B cells) from Dox-exposed leukemic Eμ-TCL1A vs iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice. Principal component analysis of transcript levels demonstrated separate clustering of the 2 genotypes (Figure 5A). We identified 1013 DEGs between the 2 genotypes, of which 81% were upregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A cells (FCh > 1.5, q ≤ 0.01, Figure 5B; supplemental Table 9), suggesting that Kdm1a suppresses global transcriptional activity in murine CLL. In line with the proapoptotic effect of a Kdm1a-KD in leukemic B cells (Figure 3I), programmed cell-death genes were overrepresented in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A cells, as per GSEA of KEGG or Hallmark pathways (Figure 5C-D), exemplified by higher mRNA abundances of proapoptotic Casp3, Cdk6, Mapk9, or Gadd45g (Figure 5E). DEGs involved in cell adhesion and migration (Figure 5F), eg Itgb2l, Rapgef3, and Cxcr4, were downregulated in splenic MCs and PB leukocytes of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (Figure 5G).

Transcriptional changes following Kdm1a depletion in Eμ-TCL1A mice. (A) PCA of RNA-seq data reveals distinct groups by genotype. Each data point represents 1 mouse. (B) Left: volcano plot showing differential gene expression between splenic MCs from Eμ-TCL1A vs from iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (light blue: upregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A, dark blue: downregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A). Right: pie chart indicating the percentage of up- and downregulated genes. One thousand thirteen genes were differentially expressed between splenic MCs from Eμ-TCL1A vs from iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice, FCh > 1.5, q ≤ 0.01, with most of them (81%) upregulated in the iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A model. (C) GSEA of DEGs between the Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A systems. The bars represent the percentage of genes from the data set that mapped to the corresponding KEGG pathways. Light blue: upregulated genes and dark blue: downregulated genes in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A splenocytes, FCh > 1.5, P ≤ .01. (D) Enrichment plots of GSEA of apoptosis (left) and p53 (right) pathways. NES and FDR q values are indicated. (E) Heatmap of DEGs associated with p53- and proapoptotic pathways. (F) Heatmap of DEGs associated with the pathway clusters of cell adhesion and migration. (G) Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactionanalysis demonstrating reduced expression of Itgb2l, Rapgef3, and Cxcr4 in splenic MCs and in PB leukocytes of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice (all P < .05, Student t test, mean ± SEM).

Transcriptional changes following Kdm1a depletion in Eμ-TCL1A mice. (A) PCA of RNA-seq data reveals distinct groups by genotype. Each data point represents 1 mouse. (B) Left: volcano plot showing differential gene expression between splenic MCs from Eμ-TCL1A vs from iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (light blue: upregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A, dark blue: downregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A). Right: pie chart indicating the percentage of up- and downregulated genes. One thousand thirteen genes were differentially expressed between splenic MCs from Eμ-TCL1A vs from iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice, FCh > 1.5, q ≤ 0.01, with most of them (81%) upregulated in the iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A model. (C) GSEA of DEGs between the Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A systems. The bars represent the percentage of genes from the data set that mapped to the corresponding KEGG pathways. Light blue: upregulated genes and dark blue: downregulated genes in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A splenocytes, FCh > 1.5, P ≤ .01. (D) Enrichment plots of GSEA of apoptosis (left) and p53 (right) pathways. NES and FDR q values are indicated. (E) Heatmap of DEGs associated with p53- and proapoptotic pathways. (F) Heatmap of DEGs associated with the pathway clusters of cell adhesion and migration. (G) Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactionanalysis demonstrating reduced expression of Itgb2l, Rapgef3, and Cxcr4 in splenic MCs and in PB leukocytes of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice (all P < .05, Student t test, mean ± SEM).

Kdm1a knockdown alters the H3K4me3 epigenetic profile in leukemic mice

Given this predominantly global transcriptional activation after a Kdm1a-KD and based on H3K4 trimethylation to be generally enriched at active gene promoters near transcription start sites, we expected more H3K4me3 marks in Kdm1a depleted leukemic cells. Indeed, H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments from splenic MCs (>85% CD19+CD5+ B cells) of leukemic Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (confirmed Kdm1a-KD in supplemental Figure 4A) identified 38 880 and 40 041 regions (predominantly promoters by log2 enrichment) to be enriched for H3K4me3, respectively. Among these, 5327 and 14 824 regions were specific for Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A, respectively (Figure 6A-C; supplemental Table 10). The patterns of distribution of enriched H3K4me3 regions at the genome-wide level did not show significant differences between Eμ-TCL1A and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A CLL cells (Figure 6C). Nevertheless, there was differential H3K4me3 enrichment with higher occupancies at specific regions in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A cells (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 4B).

Among the H3K4me3 marked TF binding motifs we identified 3 highly enriched iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A–specific sites. These were binding motifs of the krüppel–like factor family (KLF) members KLF3 and KLF1 and of Sp2 (Figure 6E). Furthermore, KEGG pathway analysis of genes associated with the iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A–specific H3K4me3 regions showed, among others, enrichment for gene sets related to apoptosis and chemokine signaling (Figure 6F). In biological process analysis defined by gene ontology terms, we detected prominent enrichments of the process “regulation of leukocyte cell-cell adhesion” (supplemental Figure 4C). These findings support our notion from the transcriptome analysis that Kdm1a-KD regulated genes are involved in apoptotic pathways and cell migration or adhesion (Figure 5C).

In addition, a total of 543 genes were both upregulated by Kdm1a-KD and associated with H3K4me3 binding sites, of which 19 were TF-encoding genes (Figure 6G). This suggests that the transcriptional effects by Kdm1a-KD are also mediated secondarily through H3K4me3-conveyed regulation of TF expression. Fittingly, an increase of H3K4me3 marks in regions surrounding genes upregulated in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A splenocytes was observed (supplemental Figure 4D). Examples include the apoptotic executioners Casp3 and Mapk9, the TFs Gata1 and Gfi1b, and the tumor suppressor Trim16 (Figure 6H). These findings were validated in human CLL44 cells with low vs high KDM1A expression (supplemental Figure 4E-F; Figure 6I-J).

Overall, our data suggest that Kdm1a acts in CLL predominantly as a transcriptionally repressive regulator by modifying H3K4, with pronounced effects on defined cell death and motility genes.

KDM1A pharmacoinhibition induces H3-methylation and apoptosis in leukemic B cells

To eventually validate KDM1A as a therapeutic target, we examined the antileukemic efficacy of 6 different compounds, reported to inhibit KDM1A25,45,46 (supplemental Table 11). In JVM3±TCL1A cells, only compound C12 markedly decreased cell viability via reduction in metabolic activity and induction of apoptosis, accompanied by phosphoactivation of P53 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage (supplemental Figure 5A-B). C12 treatment increased H3K4 and H3K9 methylation irrespective of TCL1A status, whereas the other inhibitors increased H3-methylation preferably in the TCL1A-negative parental line (supplemental Figure 5B). C12 performed similarly in a CLL cell line harboring mutant TP53 (Mec-1) and in DoHH2±TCL1A lymphoma cells (supplemental Figure 5C-D).

Next, we tested these inhibitors in primary human CLL cells that were cocultured with monocytic THP-1 cells in presence of a CpG/IL-15 cocktail (supplemental Table 12). Only C12 notably reduced cellular metabolic activity of these stimulated CLL cultures (supplemental Figure 5E). C12 induced apoptotic cell death, whereas RN1 only induced early apoptosis, represented by single annexin V positivity (supplemental Figure 5F-G). Such a pattern is described for metabolically (hyper)active senescent cells that undergo apoptotic transition.47,48 In agreement, RN1 markedly induced cellular senescence as recorded by fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside staining (supplemental Figure 5H). Nevertheless, only C12 and IMG7289 strongly induced H3K9me3 levels and PARP cleavage. C12 also increased H3K4me3 levels and P53 phosphoactivation (P < .05, Figure 7A). Interestingly, C12 and IMG7289 inhibited cell proliferation in JVM3TCL1A and Mec-1 cells (Figure 7B), which was validated via a short hairpin RNA–mediated KDM1A-KD (Figure 7C). Moreover, C12 and IMG7289 reduced the interaction of KDM1A with its coeffector Co-REST (supplemental Figure 6A), further emphasizing KDM1A-specific modes of inhibition.

KDM1A inhibition acts synergistically with antagonists of BCL2 and MDM2

Despite the availability of highly effective targeted agents, many patients with CLL experience hard-to-treat relapses under these therapies.50 Combination therapies hold the promise to prevent resistance and to minimize undesired side effects, and proposed targets include Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) or B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) in conjunction with (histone)deacetylases ([H]DACs).51,52 We, therefore, interrogated in JVM3TCL1A and Mec-1 CLL–like cells the KDM1A inhibitor C12 as a combination partner with ibrutinib, venetoclax, the pan-HDAC inhibitor panobinostat, the MDM2 inhibitor idasanutlin (the latter to reinstate P53-mediated apoptosis53; TP53 is in wild-type configuration in JVM3), and inhibitors targeting known TCL1A interactors (Figure 7D). Combinations of C12 with venetoclax showed synergistic antileukemic relationships (zero-interaction potency synergy scores49 >10, Figure 7E-F), which might be attributed to increased BCL2 levels upon KDM1A depletion or upon C12 treatment (supplemental Figure 6B-C). C12 and idasanutlin were only synergistic in JVM3TCL1A cells, likely because of the TP53 lesion in Mec-1 (Figure 7E; supplemental Figure 6B). Furthermore, conditioning of B-cell lines with sublethal dosages of C12 as well as a Kdm1a-KD in murine leukemic cells both sensitized toward venetoclax or idasanutlin (Figure 7G-H), supporting a KDM1A-dependent effect.

In THP-1 cocultured CLL cells the KDM1A inhibitors C12 and GSK showed synergistic relationships with venetoclax, whereas IMG7289 was synergistic with venetoclax and with idasanutlin (Figure 7I-J). These data indicate that KDM1A might be a suitable target for selected combination therapies in CLL.

Discussion

The epigenetic layers of chromatin dynamics and histone modulations have just started to be recognized as important disease-defining features of CLL.54 Since the first published profiling of chromatin accessibilities in CLL in 2016,19 few more studies have consolidated a concept of specific chromatin configurations and dynamic histone modifications to underly leukemic evolution, disease heterogeneity, and its relapsed/refractory state.3,44,55,56 Also, currently used treatments, such as ibrutinib, significantly reprogram patterns of chromatin accessibility and histone marks.57,58 The promise of pharmacoepigenomics in CLL to revert resistances against CD20-antibodies as well as B-cell receptor- and BCL2-inhibitors is mainly based on encouraging observations of enhanced target (re)expression and highly synergistic drug relationships toward re-established sensitivities.54,59 HME represent the central target category therein. However, besides first data on HDACs, EZH2, SIRT1, or SETD2, HME in CLL are generally poorly characterized for their dysregulation, functional relevance, and target properties.54,60-62

To our knowledge, in this first report on KDM1A in CLL, we establish an actionable oncogenic role of this lysine-specific demethylase. We identify KDM1A as a novel effector of TCL1A in B cells adding to our functional concept of this oncogenic chaperone. This protein interaction enhances the catalytic activity of KDM1A and fittingly, MS-based analyses of histone posttranslational modifications demonstrate lower H3K9me2/3 upon introduction of TCL1A into malignant B cells. Overexpressed in CLL, high-level KDM1A and associated transcriptional clusters correlated with aggressive disease features and inferior clinical outcomes in the 337 patient CLL8 trial cohort. Genetic KDM1A depletion in Eμ-TCL1A CLL mice suppresses leukemic growth via CLL-cell intrinsic as well as milieu-mediated mechanisms. Through integration of KDM1A-associated transcriptome and H3K4me3 changes in murine CLL, we establish KDM1A as a predominant transcriptional repressor, whose specifically modified histone methylation profiles regulate defined B-cell survival pathways. We finally demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of KDM1A alters H3K4/9 methylation and induces apoptosis in CLL cells and therein also cooperates with antagonists of BCL2 and MDM2.

We consider an induced depletion of Kdm1a in leukemic Eμ-TCL1A mice (iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A) as a highly informative model. It allowed the establishment of Kdm1a’s leukemic relevance in the context of its catalytically activating interactor TCL1A. Such whole-organismal Kdm1a loss can partially mimic the systemic effects of pharmacologic targeting of KDM1A. However, in contrast to enzymatic inhibition, a genetic KDM1A downregulation impairs its scaffolding function as well. The Kdm1a-KD reduced leukemic burden in PB and lymphoid tissues by inducing CLL-cell apoptosis and impeding their proliferation, which translated into prolonged animal survival. Importantly, to our knowledge, we provide here first evidence that such a systemic Kdm1a impairment acts as antileukemic not only via B-cell intrinsic mechanisms, but also by reshaping the composition of the local micromilieu (T, stromal, and monocytic cells). Moreover, reduced KDM1A in murine and human stromal and monocytic cells diminished their ability to provide prosurvival or proproliferative support to cocultured CLL cells. In agreement, KDM1A inhibition had been implicated in modulating the tumor micromilieu in breast cancer, eg, by affecting the stromal compartment or the infiltration of T cells and macrophages.63-65 Interpretations of such findings also need to provide room for consequences of a myeloid-biased differentiation triggered by KDM1A inhibition.66 Further studies also need to address differential pro- or antileukemic roles of developmental stages and polarized subsets of these milieu components regulated by KDM1A to anticipate the effects of KDM1A inhibitor treatments.

Our data also provide insights into the molecular networks regulated by KDM1A in CLL. SLAMF6, a key rheostat of the interactions between T follicular helper cells and germinal center B cells,40 was among the top 10 upregulated genes in KDM1Ahigh CLL. Targeting SLAMF6 was effective in xenografts derived from patients with CLL.67 High KDM1A also correlated with low FOS family (ie, FOS and FOSB) expression, which already indicated poorer outcomes in CLL.68 Moreover, from our transcriptome analysis of splenocytes from iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice we infer that Kdm1a is a transcriptional repressor of proapoptotic genes and pathways (eg, p53 signaling). It also seems to have activating effects on molecules involved in B-cell homing and adhesion, such as Itgb2l and Rapgef3 (mediators of the cross talk between malignant B cells and their micromilieu)69 or the homing chemokine Cxcr4, whose overexpression correlates with inferior prognoses in patients with CLL.70

In the subsequent H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments the deregulated cell-death pathway molecules upon Kdm1a targeting can be associated in part with altered H3K4me3 at the involved gene regions. Additionally identified H3K4me3-mediated Kdm1a targets were KLF1 and KLF3. KLFs are essential in promoting marginal-zone B–cell fate programs.71,72 Discrepancies between the observed global changes in gene expression and predicted targets of enriched H3K4me3 binding upon Kdm1a depletion indicate that (a) alterations in H3K4me3 do not exclusively dependent on KDM1A, (b) other KDM1A targets (eg, H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20)21 might be involved, and (c) KDM1A also demethylates nonhistone proteins, such as TFs.22

Finally, our assessment of the therapeutic potential of KDM1A inhibitors in CLL revealed that some (eg, C12, IMG7289) are effective at increasing H3K4/K9 methylation and in inducing CLL cell death, whereas others that are clinically active in acute myeloid leukemia or other diseases,25 showed limited activity here. It appears plausible that different disease biologies and various KDM1A specificities of the compounds (Sonnemann et al73 and supplemental Table 11) contribute to these differences in biochemical and cell-biological outcomes. In alignment with our enriched KDM1A target pathways and following the concept that targeting HME is an effective strategy of drug (re)sensitization, C12 and GSK showed synergisms with BCL2-inhibition. Importantly, IMG7289, which is currently in clinical trials for hematological malignancies, showed the highest synergisms with BCL2- and MDM2-inhibition in CLL cells. These findings highly warrant the development of optimized KDM1A inhibitors and thorough synergy studies, ie, in relapsed/refractory CLL.

Overall, as the first description of KDM1A in CLL, we established the pathogenic relevance, molecular effector networks, and target properties of this HME, both in the leukemic cell and in components of its micromilieu. This provides a rationale for KDM1A inhibition in CLL.

Acknowledgments

CLL sample acquisition was supported by the Biobank of the Center for Integrated Oncology Aachen-Bonn-Cologne-Duesseldorf funded by the German Cancer Aid. Healthy blood donors, who consented to the use of residual material of their donation, are acknowledged. The analysis of GEP data from the CLL8 trial was supported by the German CLL Study Group. The authors thank R. Schüle (Freiburg, Germany) for providing the iKdm1aKD mice. Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted at the Cologne Excellence Cluster on Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases proteomics facility. Use of an Olympus microscope was provided by the microscopy core facility of the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC).

M. Herling (principal investigator) and E.V. (Female Research Grant) were funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, HE-3553/3-2) as part of the collaborative research group KFO-286. M. Herling is funded by the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation (R12/08). E.V. also received support from the Köln Fortune Program (110/2012), German Cancer Aid (70112788), as well as the Nolting, Kaethe-Hack, and Hochhaus Foundations. This work was also supported by the CMMC (Project C08; Project 23-RP, to M. Herling and E.V.). Q.J. was funded by a scholarship of the China Scholarship Council ([2017]3109). M.R.S. received funding through the DFG KFO-286 and SFB1399, and the CMMC.

The authors dedicate this article to their colleague and dedicated mentor Elena Vasyutina, who, although no longer with us, continues to inspire by her outstanding example as a creative scientist and committed teacher.

Authorship

Contribution: E.V., Q.J., J.S., J.B., and M. Herling were responsible for experimental design and data analysis; Q.J., E.V., J.S., F.G., O.O., C.A., Z.W., C.D.H., P.M., M.K., H.Y.R., Y.Z., J.A., K.E.-J., C.J.B., and M.O., performed experiments and data analysis; J.B., S.R., K.F., B.J., S.S., and M. Hallek analyzed GEP and clinical data of the CLL8 trial; RNA-seq data were analyzed by P.W., P.S.D., and Q.J.; A.P., Q.J., and M.R.S. performed ChIP-seq data analysis; B.P., R.E., and Q.J. analyzed the tissue cytometric data; C.D.H., K.R.C., and L.V.A. provided and analyzed the data of the FCR300 trial; B.G. was responsible for healthy donor samples; Q.J., E.V., J.S., and T.P. performed magnetic resonance imaging scans of mice; and Q.J., J.S., T.M., and M. Herling prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Elena Vasyutina died on 24 February 2020.

Correspondence: Marco Herling, Department of Hematology, Cellular Therapy, and Hemostaseology, University of Leipzig, Liebigstr 22, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; e-mail: marco.herling@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

References

Author notes

∗E.V. and M. Herling contributed equally to this study.

Microarray data are available at GEO under accession number GSE126595. RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data were submitted to GEO under accession number GSE190108 and GSE188536. The mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomics data are deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium (project #PXD030773). MS data of histone posttranslational modifications are available at the Chorus repository (https://chorusproject.org/; project #1743).

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Marco Herling (marco.herling@medizin.uni-leipzig.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![TCL1A interacts with KDM1A and enhances its demethylase activity. (A) Experimental setting of MS of TCL1A coimmunoprecipitations (co-IPs) in human CLL B cells (nonmalignant B cells from tonsils as biological controls). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) co-IPs in CLL B cells served as technical controls. CLL sample strata: immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) mutated (M-CLL, N = 6) vs IGHV unmutated (U-CLL, N = 5). Proteins that showed a significant enrichment between the IgG control and CLL samples (459 proteins) or tonsils (889 proteins) were considered TCL1A interacting partners (Welch test, FDR q-value ≤ 0.05, FCh ≥ 2.0). Four hundred nine and 407 TCL1A-interacting proteins were identified in M-CLL and U-CLL cells, respectively (324 proteins overlapped between both subsets). (B) Left: selected pathways identified by overrepresentation analysis (ORA; supplemental Table 6), bars illustrate the percentage of involved proteins from the TCL1A interactome within each pathway. Right: heatmap of chromatin-modifying enzymes that interact with TCL1A protein. KDM1A (∗) tended to interact with TCL1A at a higher abundance in U-CLL than M-CLL (P = .052, Mann Whitney test). (C) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies in primary CLL B cells cocultured with differentiated THP-1 monocytic cells supplemented with CpG and IL-15 for 36 hours to induce proliferation (Ki67+ 38.9%-54.1%). Each lane represents an individual CLL sample. (D) Immunoblots of TCL1A co-IPs from Eμ-TCL1A splenic leukemic cells (2 mice) treated with DNA double strand break–inducing etoposide (10 μM, at 0, 1, and 3 hours). (E) Histone demethylase activity assay: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in DoHH2 B cells transfected with TCL1A (N = 3, each experiment in duplicates; P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (F) Quantitative MS analysis of histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in DoHH2±TCL1A B cells (N = 3 independent experiments). Left: principal component analysis (PCA) of MS data showing distinct groups by the presence of TCL1A (blue DoHH2, red DoHH2TCL1A). Each data point represents 1 independent experiment. Middle: heatmap showing differential histone single marks in TCL1A positive and negative DoHH2 cells. Right: lower levels of H3K9me2 (P = .013) and H3K9me3 (P < .001) in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells (Student t test, mean ± SEM). (G) Immunoblots showing lower levels of H3K9me3 in TCL1A-positive DoHH2 cells. (H) Top: immunoblots showing KDM1A levels in 14 CLL (lanes = case numbers). Bottom: higher demethylase activity of KDM1A in cases with higher KDM1A levels as per KDM1A activity assay (N = 4 CLL per group, P = .028, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM; KDM1A levels shown in top panel). Supplemental Figure 1A shows no correlation between KDM1A and H3K9me2/3 protein signals (nonexclusive impact of KDM1A on H3K9me2/3 levels). (I) Immunoblots of co-IPs using IgG or TCL1A antibodies illustrating higher abundance of TCL1A-KDM1A interaction in primary CLL B cells vs T-PLL T cells. Each lane represents an individual B-CLL or T-PLL sample. RFU, relative fluorescence units.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/142/1/10.1182_blood.2022017230/2/m_blood_bld-2022-017230-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1769150624&Signature=lvdU6arKYpKiuwULcBcHLpbb9Hu2UeFPLTeqNAarNlmEw~a4nVs~M-LI4OcX62YvK-Itx0dzwVY4im~-zdJiRem8MiLRDKWN1qJzRvKuDL1YgaGWb3ylcDauTjiI7LwT96E69FBKLiyBou12Gc3whMEWbL4bPphkc-vMK~2gDlBsQaLBc~5vdWeyToP8aqsFP4KgFhYDXmoAF1k9AZ9zxO0MkO5X9VlTVjDNXW7iD4xIJqMn9ZMEqSMGi1-xk9d1Oa7NcPGN0~9lAOhXpTSqDWJjniH4B3~~xh7hB3kcLiYWMjvzLiB0ztLxKOym8KR8R3eOVeP960qW4m0ytKplYA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Knockdown of Kdm1a reduces leukemic burden in vivo. (A) Setup of mouse experiments. Top: for survival analyses, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼50 to 70 × 109/L) were treated with Dox to induce Kdm1a-KD and observed until the clinical endpoints (defined in supplemental Materials). Blood was taken every week to monitor leukemic load and changes in other blood parameters. Bottom: for RNA-seq and cryosectioning, leukemic mice (WBCs ∼30 × 109/L) were exposed to Dox for 2 weeks. For ChIP experiments, mice were treated with Dox for 2 weeks when WBCs reached 80 to 100 × 109/L. (B) Significantly longer survival (Log-rank test) of Dox-treated leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red, 12 females, median 67 days) vs Dox-exposed leukemic Eμ-TCL1A mice (blue, 12 females, median 39 days, P = .018) or vs non-Dox–exposed leukemic iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (green, 9 females, median 41 days, P = .036). (C) Significantly lower WBCs in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (N = 8, red) leukemic mice under Dox treatment as compared with Eμ-TCL1A (N = 7, blue, P = .01, 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (D) Lower total number of PB leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells (flow cytometry) in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 6, red) in comparison with those of Eμ-TCL1A (N = 6, blue, P = .013, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). End: end point of survival experiment. (E) Lower percentage of CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens and BM of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A mice under short term (≤2 weeks, left) or long term (≥4 weeks, right) in vivo Dox treatment (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SEM). (F) Top: representative images (taken at 60× original magnification) of immunofluorescent B220/KDM1A/Hoechst staining of spleen sections from Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice under Dox treatment for 2 weeks (B220 green, KDM1A red, Hoechst blue). Bottom: quantification of B220/KDM1A signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest showing reduced population of KDM1A+ cells (left, P < .001), B220+ B cells (middle, P = .002), and KDM1A+B220+ cells (right, P = .009) in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (red) than that of Eμ-TCL1A (blue) mice (Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (G) Spleen volumetry after magnetic resonance imaging scanning of Eμ-TCL1A (left) and iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A (right) mice (WBCs ∼50 × 109/L) treated with Dox for 6 weeks. Representative images of abdominal region (red dashed line highlights splenic circumference). Bar chart displays splenic volumes before and under Dox treatment at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Both groups presented significantly enlarged spleens at 6 weeks (N = 5, P < .05, Student t test, mean ± SEM). (H) Tissue cytometer analysis of B220/Ki-67 immunofluorescent signals of spleen sections by StrataQuest. Left: representative tissue cytometry plots show B220+/Ki-67+ B cells in spleens (Eμ-TCL1A blue, iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A red). Right: quantified signal implicates decreased Ki-67+ B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A vs Eμ-TCL1A animals (N = 4 of each group, P = .029, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). (I) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic leukemic B cells in spleens (annexin V staining). Left: representative density plots and histograms illustrate a smaller population of leukemic CD19+CD5+ B cells and a higher percentage of apoptotic leukemic cells in iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A mice after 2 weeks of Dox treatment (comparison to Eμ-TCL1A). Right: higher percentages of apoptotic CD19+CD5+ leukemic B cells in spleens of iKdm1aKD;Eμ-TCL1A compared with that of Eμ-TCL1A mice (N = 5 of each group, P = .008, Mann Whitney test, mean ± SD). BMMCs, bone marrow MCs.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/142/1/10.1182_blood.2022017230/2/m_blood_bld-2022-017230-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1769150624&Signature=RMQm2c0w1GvWe8bS7pxW3TYsxwhDXTDdV-wlDPdAbXCCA04DEwHIrDNG86ajGW2TL25Hv8bnkChgsgrYCb73RlsgFgbH57~F7LIojuU9W~InvHYxFyhbh6g-M1AU0l5jyotcYmrGQXrUjLE8AiNp3VFpYTZz0MH1eq6JUYXY5alOQ8gqFmfFPvqe9XtnbUtZhuQnYbcUdVn25ddGJ4r-CQxax6enKVyCAwICtjuzxG5IcXrVFJXfUZtANVIB7uZfkSUKFOyM5IuO7MKEOjXK1SDVzxNdgQzQjC-Fh17lEBu-zOTQ4oxNNaQwtC60Ul33arW6Q6wp~vEiq8vxgmXsIQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)