In this issue of Blood, Yamamoto et al1 investigate the associations between parental occupational exposure to anticancer agents, anesthetics, or ionizing radiation and childhood cancer in the offspring using prospectively collected data from the large Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) (see figure). The authors report a nearly eightfold increased risk of leukemia among children aged 1 to 3 years whose mothers were occupationally exposed to anticancer agents during pregnancy. Contrariwise, neither maternal occupational exposure to ionizing radiation or anesthetics during pregnancy nor paternal occupational exposure to these agents prior to conception were associated with cancer risk in the offspring. The study builds upon and, to some extent, contrasts with findings from a previous publication from the JECS demonstrating increased risk of neuroblastoma among infants whose mothers reported occupational exposure to radiation during pregnancy.2

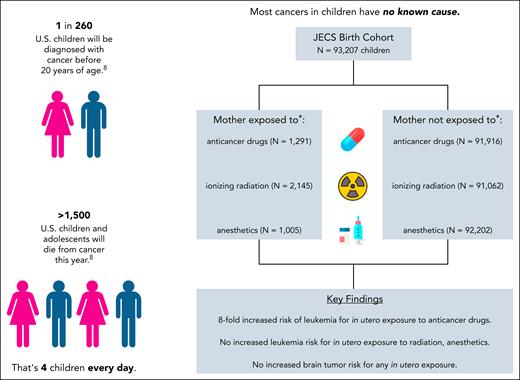

Risk of leukemia and brain tumors among children whose parents reported occupational exposure to anticancer drugs, ionizing radiation, or anesthetics in the JECS. Cancer remains the leading cause of death by disease in children older than 1 year, and most cases have no known etiology. JECS investigators sought to determine whether exposure to anticancer drugs, ionizing radiation, or anesthetics reported by mothers during pregnancy or by fathers in the 3 months prior to becoming aware of their partner's pregnancy was associated with cancer risk in offspring up to age 3 years. Maternal exposure to anticancer drugs during pregnancy was associated with an eightfold increased risk of childhood leukemia. No associations were observed for leukemia in connection with maternal exposure to ionizing radiation or anesthetics, brain tumors in connection with any maternal exposure, or childhood cancer in connection with paternal preconception exposures. ∗Occupational exposure during pregnancy. This figure was prepared using images from Flaticon.com.

Risk of leukemia and brain tumors among children whose parents reported occupational exposure to anticancer drugs, ionizing radiation, or anesthetics in the JECS. Cancer remains the leading cause of death by disease in children older than 1 year, and most cases have no known etiology. JECS investigators sought to determine whether exposure to anticancer drugs, ionizing radiation, or anesthetics reported by mothers during pregnancy or by fathers in the 3 months prior to becoming aware of their partner's pregnancy was associated with cancer risk in offspring up to age 3 years. Maternal exposure to anticancer drugs during pregnancy was associated with an eightfold increased risk of childhood leukemia. No associations were observed for leukemia in connection with maternal exposure to ionizing radiation or anesthetics, brain tumors in connection with any maternal exposure, or childhood cancer in connection with paternal preconception exposures. ∗Occupational exposure during pregnancy. This figure was prepared using images from Flaticon.com.

In the context of pediatric cancer, occupational exposures affecting health care workers have received scant attention. The first report of a potential association between in utero ionizing radiation and childhood cancer was published in 1956,3 but the concept has remained controversial, and subsequent studies focused on other pathways of exposure.4 Similarly, although the increased incidence of second malignant neoplasms among survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer survivors who received chemo- or radiotherapy is now well characterized,5-7 the potential role of maternal exposure to these agents in the child’s first primary malignant tumor has been understudied.2 Indeed, a recent umbrella review of environmental factors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common cancer in children,8 presented no findings related to parental occupational exposure to medical agents or ionizing radiation.9 Thus, the present study is noteworthy for the fact that it is the first to demonstrate an association between exposure to anticancer agents in pregnant people and leukemia in their offspring; for the strength of this association (as measured by the relative risk); and for the use of prospectively collected data from a large birth cohort, a rarity among epidemiological studies of childhood cancer. Prospective ascertainment of exposure status reduces recall bias that may introduce error in the more common case-control design.

While providing important insights into the potential causes of acute leukemia in children, the authors’ work also highlights important knowledge gaps. Only cancers diagnosed within the first 3 years of life were evaluable; further work will be necessary to replicate these findings and determine whether the exposures in question associate with tumors diagnosed in older children, adolescents, and young adults. Should the study’s findings be validated, it is anticipated that there will be concern around exposure to anticancer agents among people who are or may become pregnant, but careful characterization of dosages and critical windows of exposure will be necessary for proper risk mitigation.

Intriguingly, no cases of infant leukemia were observed among individuals whose mothers reported handling anticancer agents during pregnancy. These data suggest that there may be enrichment (or conversely, depletion) of certain leukemia subtypes among children exposed to anticancer agents in utero. Further work incorporating information on tumor mutational signatures10 and molecular characteristics may be informative for characterizing the key events and pathways in childhood cancer initiation and progression following in utero exposure to anticancer agents.

The present investigation suggests a novel mechanism by which environment may influence the risk of childhood cancer and should stimulate further research into these important unanswered questions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.