Key Points

HSCT is recommended for patients achieving PR after initial treatment; patients with CR could adopt a wait-and-see strategy.

Prognostic risk models of adult patients with EBV-HLH with or without HSCT were developed by Lasso-Cox regression.

Visual Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome characterized by aberrant immunological activity with a dismal prognosis. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated HLH (EBV-HLH) is the most common type among adults. Patients with EBV infection to B cells could benefit from rituximab, whereas lethal outcomes may occur in patients with EBV infection to T cells, nature killer cells, or multilineages. The necessity of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in adult patients with EBV-HLH remains controversial. A total of 356 adult patients with EBV-HLH entered this study. Eighty-eight received HSCT under medical recommendation. Four received salvage HSCT. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for patients who underwent HSCT was 48.7% (vs 16.2% in patients who did not undergo transplantation; P < .001). There was no difference in OS between patients who received transplantation at first complete response (CR1) and those at first partial response (PR1) nor between patients at CR1 and CR2. Patients who received transplantation at PR2 had inferior survival. The rate of reaching CR2 was significantly higher in patients with CR1 than PR1 (P = .014). Higher soluble CD25 levels, higher EBV-DNA loads in plasma after HSCT, poorer remission status, more advanced acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and the absence of localized chronic GVHD were associated with inferior prognosis (P < .05). HSCT improved the survival of adult EBV-HLH significantly. For patients who achieved PR after initial treatment, HSCT was recommended. A wait-and-see strategy could be adopted for patients who achieved CR after initial treatment but with the risk of failing to achieve CR2.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rapidly progressive, life-threatening syndrome arising from excessive immune activation.1 In accordance with etiology, HLH can be categorized into primary (pHLH) and secondary HLH (sHLH).2 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated HLH (EBV-HLH) is one of the most common subtypes of sHLH, notably in Asia.3 The clinical course of EBV-HLH is heterogeneous, ranging from self-limiting to aggressive course with fatal outcomes.4 Patients with EBV infection limited to B cells could benefit from rituximab.5 In contrast, EBV-positive T and nature killer (NK) cells are challenging to eradicate, leading to disease recurrence and a poor prognosis.6 Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been demonstrated to be the most reliable radical treatment for pHLH7,8 and malignancy-associated HLH.9,10 HSCT can also improve the prognosis of children with refractory/relapsed EBV-HLH,6,11 but studies in adults are scant. This study aimed to determine whether adult patients with EBV-HLH with EBV infection to T cells, NK cells, or multilineages could benefit from transplantation, as well as the optimal time of transplantation.

Materials and methods

Patients

Adult patients with confirmed EBV-HLH admitted to Beijing Friendship Hospital from January 2015 to August 2021 were included in this study. Ethics approval was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (2020-P2-096-01). Informed written consent was obtained following the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 264 patients have been reported in our previous study.12

Inclusion criteria required that HLH be diagnosed according to the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria.1 NK-cell activity and expression levels of cytotoxic function–related proteins were examined in all patients. Patients with significant abnormalities or recurrent HLH underwent gene sequencing to exclude pHLH. All patients received bone marrow (BM) aspirate, BM biopsy, immunophenotyping, chromosome, lymph node ultrasound, and abdominal ultrasound. Patients with enlarged lymph nodes underwent lymph node biopsy or positron emission tomography–computed tomography to exclude malignant disease.

EBV-HLH was defined as the occurrence of HLH ascribed to EBV infection without known immunodeficiencies. Chronic active EBV disease (CAEBV) was diagnosed following the guidelines proposed by the Japanese Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare research team. In situ hybridization (ISH) was applied to detect the EBV genome or EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in tissues. EBV DNA load in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The threshold value was 500 copies per mL. Diagnosis of EBV infection was based on the positive result of in situ hybridization or RT-PCR. EBV-infected cell lineages were determined by performing RT-PCR on PBMCs fractioned into B, T, and NK cells using magnetic beads. All patients were regularly monitored for EBV-DNA load (both plasma and PBMC) as well as the EBV-infected cell lineages. EBV-DNA load was recorded in this study 1 week after HSCT for patients who received HSCT.

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) incomplete clinical data; (2) pHLH or other subtypes of sHLH with concomitant EBV infection; and (3) age <18 years.

Patients eligible for transplant

Patients who fulfilled the following were considered as eligible for transplant: (1) age <60 years; (2) without severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, cardiac disease, or active infections; (3) achieved HLH remission; and (4) had EBV infection to T/NK/multilineages. For these patients, HSCT was medically recommended. However, whether HSCT proceeded or not was also determined by the donor availability, the patient’s willingness, and the cost.

HLH status before HSCT

Efficacy was assessed every 2 weeks with indicators including body temperature, serum soluble CD25 (sCD25), ferritin (FER), blood cell count, alanine transaminase (ALT), triglyceride (TG), phagocytosis, and central nervous system (CNS) involvement.13 Complete response (CR) was defined as a return to normal for all of the above indicators. Partial response (PR) was defined as at least a 25% improvement in ≥2 symptoms/laboratory indicators: sCD25 level decreased by one-third or more; FER and TG decreased by ≥25%; neutrophil increases by 100% to >0.5 × 109/L for patients with counts <0.5 × 109/L or by 100% with normalization for patients with counts between 0.5 × 109/L and 2.0 × 109/L; and a decrease of >50% for patients with ALT >400 U/L. Nonresponse (NR) was defined as not meeting the above criteria.

CR1/PR1

Patients underwent allogeneic HSCT as soon as they reached CR or PR with initial induction therapy (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood website).

CR2/PR2

Patients received allogeneic HSCT after obtaining CR or PR with salvage therapy due to refractory or relapsed disease (supplemental Figure 1A).

Refractory/relapsed

Refractory was defined as fail to achieve at least PR with first-line induction therapy. Relapse was defined as responded to the induction therapy but recurred.

CNS involvement

CNS involvement was considered with any following signs : psychiatric and or neurological symptoms, CNS imaging abnormalities, cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities.

Conditioning regimen

Myeloablative conditioning regimens were performed in allogeneic HSCT with total body irradiation (TBI)/Cy/VP-16 or Bu/Cy/VP-16. Bu/Cy/VP-16 consisted of etoposide at 10 mg/kg on days –9 to –8, busulfan 3.2 mg/kg per day on days –7 to –5, and cyclophosphamide at 1.8 g/m2 per day on days –4 to –3. TBI/Cy/VP-16 consisted of TBI of 900 cGy on days –8 to –7, etoposide at 10 mg/kg on days –6 to –5, and cyclophosphamide at 1.8 g/m2 per day on days –4 to –3.

Prevention of aGVHD

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis included anti-human thymocyte globulin, cyclosporine A, and mycophenolate mofetil. Rabbit anti-human thymocyte globulin was given once daily on days –2 to –1 with a total dose of 2.5 mg/kg in patients who had HLA-matched related donor or on days –3 to –1 with a total dose of 7.5 mg/kg in patients with haploidentical donor or unrelated donor. With cyclosporine A beginning doses of 3 mg/kg per day, target levels were 150 to 200 g/L; thereafter, doses decreased and were withdrawn 180 days after HSCT without acute GVHD (aGVHD). From days +5 to +35, mycophenolate mofetil was given at a dose of 15 mg/kg every 8 hours (with a daily maximum of 3000 mg), and it was stopped in the absence of GVHD.

Hematopoietic recovery

Neutrophil engraftment was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count >0.5 × 109/L in 3 consecutive days. Platelet engraftment was defined as achieving a platelet count >20 × 109/L without platelet transfusions for 7 days. Erythrocyte engraftment was defined as maintenance of hemoglobin (Hb) >90 g/L without transfusions for 15 days.14

Follow-up

Telephone follow-ups were conducted based on hospitalization information. Starting point was the day the patient was diagnosed with EBV-HLH; end point was on 31 August 2022 or death.

Statistical analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software and R v4.1.2 were used. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the independent samples t test was used for the comparison of groups. Nonnormally distributed data were presented by median (range), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the 2 groups. Categorical variables were expressed as (frequency [percentage]), and intergroup comparisons were performed using the χ2 test. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in subgroups were assessed by the log-rank test. Multivariable analysis is performed using Cox proportional hazards regression. The crucial point is that patients in the HSCT group were naturally alive at transplant and thus had a better prognosis than those in the non-HSCT group. To address this phenomenon, known as immortal-time bias, a time-dependent Cox regression model was used to evaluate the association between patient characteristics and OS. HSCT was an internal time-dependent variable. Based on the median survival of non-HSCT group and the median interval from diagnosis to HSCT, cutoff point was selected. Follow-up of patients was split into 2 observation intervals and to estimate regression coefficients. Transplant recipients contributed to time-at-risk to the non-HSCT group if they received HSCT beyond the cutoff point after HLH diagnosis.

Lasso regression was used with an iterative 10-fold crossvalidation procedure to filter the factors associated with prognosis. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to determine the appropriate bounds for variables. The Cox regression model was used to produce a model based on these factors. Patients without HSCT were randomly divided into the training set and the validation set in a 1:1 ratio, and internal validation was used to verify the model performance. Patients who received HSCT (except 4 cases with NR) in this study were used as a training set. Twenty-three adult patients with EBV-HLH who underwent HSCT in our center from September 2021 to April 2023 were used as the validation set. Model validation of patients who underwent transplantation was performed through external validation (supplemental Figure 1B). The C-index and calibration curve were used to assess the discrimination and consistency of the model, respectively. P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

A total of 356 patients with EBV-HLH were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. A total of 177 patients (60.4%) were positive for EBER-ISH. EBV infection was limited to B cells in 15 patients, in whom transplantation was not performed. In 89 patients, EBV-infected multilineages of lymphocytes, and there was a preponderance of EBV-positive NK cells in 34 cases. EBV genomes were detected in T cells, NK cells, or both of the remaining patients. Sixty-six patients had a history of CAEBV, and the median time from CAEBV diagnosis to EBV-HLH diagnosis was 156 days (5-4219). Highly elevated levels of FER (medium, 2182.9 μg/L) and sCD25 (medium, 22 217.5 pg/mL) were found at diagnosis, as well as a high EBV-DNA viral load in plasma and PBMCs with a median of 23 000 and 40 000 copies per mL, respectively. The median levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-18, IL1RA, and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) were all higher than the upper limit of normal.

A total of 199 patients were considered eligible for transplant, of whom 88 received HSCT and 111 did not. HSCT was not medically recommended in 157 patients, of whom 4 patients received HSCT due to solid willingness. Eventually, 92 patients performed HSCT. The median interval from diagnosis to HSCT was 83 days (26-1035). Detailed reasons for performing HSCT or not were summarized in Figure 1A. Nontransplant patients were older and had lower blood counts, higher bilirubin, creatinine (Cr), FER, and EBV loads than patients receiving HSCT (P < .05; supplemental Table 1).

Cohort details. (A) Detailed reasons for performing HSCT or not. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of entire cohort (n = 356).

Cohort details. (A) Detailed reasons for performing HSCT or not. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of entire cohort (n = 356).

Treatment process and HLH status

A total of 170 patients received doxorubicin-etoposide-methyprednisolone (DEP)/L-asparaginasum-DEP (LDEP) regimen initially, with a remission rate of 82.9% (141/170) and a CR rate of 51.8%. Sixty-three patients received DEP/LDEP regimen as salvage treatment, 60.3% of them reached remission, and the CR rate was 36.5%. A total of 179 patients had EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment. Among 111 from the non-HSCT cohort, the EBV-DNA load was 2100 copies per mL (0 × 107 to 1.7 × 107) in PBMC and 6500 copies per mL (0 × 106 to 8.7 × 106) in plasma. Sixty-eight patients from the HSCT cohort had EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment. The EBV-DNA load was 0 copies per mL (0 × 106 to 3.2 × 106) in PBMC and 16 000 copies per mL (0 × 107 to 2.3 × 107) in plasma. Among the HSCT cohort, 22 patients were initially treated with the HLH-94/2004 regimen. Fifteen patients (68.2%) achieved remission. Sixty-eight patients received DEP/LDEP regimen as initial treatment, and 59 patients (86.8%) achieved remission. Sixteen patients (17.4%) were refractory to initial therapy, and 13 (14.1%) achieved CR/PR after salvage therapy. Twenty-two patients underwent HSCT at CR1 and 29 patients at PR1. Twenty-five (27.2%) had relapses before HSCT, including 11 with CR, 13 with PR, and 1 with NR after salvage treatment. Four (4.3%) with persistent NR underwent salvage transplantation in accordance with the strong wishes of the patients and their families. Among patients who were eligible for transplant, 17 of 28 patients (60.7%) with CR1 reached remission after second-line treatment, with a CR2 rate of 46.4% (13/28) and a PR2 rate of 14.3% (4/28). Twenty-seven of 54 patients (50%) with PR1 reached remission after second-line treatment, with a CR2 rate of 20.4% (11/54) and a PR rate of 29.6%. The rate of reaching CR2 was significantly higher in patients with CR1 than PR1 (P = .014).

Conditioning, donor typing, engraftment, and GVHD

The conditioning regimen was TBI/Cy/VP-16 for 78 patients (84.8%) and Bu/Cy/VP-16 for the rest. A total of 79 patients (85.9%) had a haploidentical donor, and 13 (14.1%) had a matched-related donor. All donors were examined for EBV-related antibodies and EBV-DNA load before HSCT. EBV-related immunoglobulin G were positive in all donors but with negative immunoglobulin M and EBV-DNA. The stem cell source was the peripheral blood stem cell in all patients. The median time of leukocyte engraftment was 13 days (10-23) after HSCT and was 13 days (8-43) for platelet. Primary graft failure was observed in 1 patient. Patients were regularly evaluated for chimeric status after transplantation, with 61 (69.3%) sustaining full donor chimerism (FDC). Twenty-one (23.8%) converted from mixed chimerism (MC) to FDC. Six patients (6.8%) sustained MC, all of whom ultimately died. The incidence of MC in patients with EBV infection to all lineages, all lineages (NK-dominant), NK, T, and NK/T were 14.3% (3/21), 35.7% (5/14), 52.9% (9/17), 29.2% (7/24), and 25.0% (3/12), respectively. The incidence of MC was significantly higher in patients with NK and all lineages (NK-dominant) than others (P = .03). Twenty-six patients received donor stem cell infusion (DSI) after transplantation, of whom 6 (23.1%) survived; 17 received donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), of whom 7 (41.2%) survived. aGVHD was observed in 77 of 92 patients (83.7%). The cumulative incidence of aGVHD grades 2 to 4 was 63.1% (58/92), and nearly half were grade 2 (48.9%). Only 3 patients had grade 4 aGVHD. Thirty-six patients (39.1%) developed chronic GVHD (cGVHD) during long-term follow-ups, all of which were localized and mild. The occurrence of aGVHD (P = .686) and cGVHD (P = .505) was not associated with donor type.

Outcomes

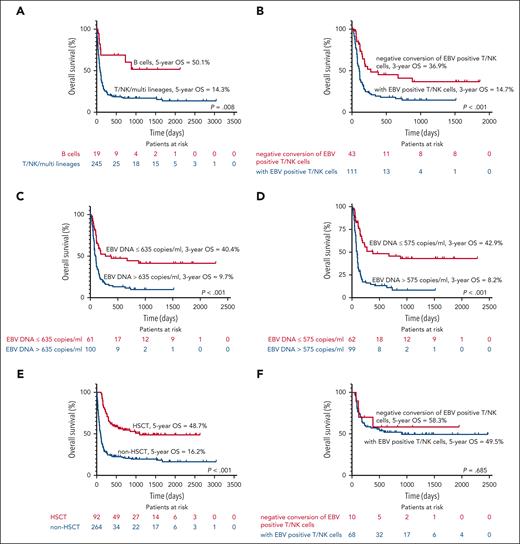

Outcomes of the entire cohort

The median follow-up of the entire cohort was 967 days (2-3045). At the last follow-up, 123 patients (34.6%) were alive, with a median survival time of 153 days. The 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year probability of survival were 76.1%, 44.9%, 34.2%, 30.2%, 27.4%, and 25.0%, respectively (Figure 1B). Of 264 patients who did not receive transplantation, the 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 67.5%, 30.8%, 23.5%, 21.0%, 19.5%, and 16.2%, respectively. Among non-HSCT group, EBV infection limited to B cells was associated with superior outcomes (Figure 2A). Detection of EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment was associated with a worse prognosis (P < .001; Figure 2B). EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after initial treatment over 635 copies per mL in PBMCs and 575 copies per mL in plasma was also associated with a worse prognosis (P < .001; Figure 2C-D). HSCT improved the survival of patients with EBV-HLH remarkably (P < .001; Figure 2E). The 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 100%, 81.5%, 62.0%, 54.6%, 48.7%, and 48.7%, respectively, among the HSCT cohort. In both patients with CAEBV (5-year OS, 66.9% vs 25.4%; P < .001) and acute EBV infection (5-year OS, 41.9% vs 14.8%; P < .001), transplantation significantly improved survival. OS of HSCT patients was not affected by EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after treatment in PBMC or plasma. Detection of EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment did not affect the OS (P = .685; Figure 2F). HSCT also diminished the recurrence rate of HLH (22.8% vs 36.7%; P = .015).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients. (A) OS according to EBV-infected cell lineages. (B) OS based on the whether EBV-positive T/NK cells were detected or not at 8 weeks after initial treatment. (C) OS according to EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after initial treatment in PBMC. (D) OS of according to EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after initial treatment in plasma. (E) OS of patients who received HSCT compared with those who did not. (F) OS based on whether EBV-positive T/NK cells were detected at 8 weeks after initial treatment among patients who underwent HSCT.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients. (A) OS according to EBV-infected cell lineages. (B) OS based on the whether EBV-positive T/NK cells were detected or not at 8 weeks after initial treatment. (C) OS according to EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after initial treatment in PBMC. (D) OS of according to EBV-DNA load at 8 weeks after initial treatment in plasma. (E) OS of patients who received HSCT compared with those who did not. (F) OS based on whether EBV-positive T/NK cells were detected at 8 weeks after initial treatment among patients who underwent HSCT.

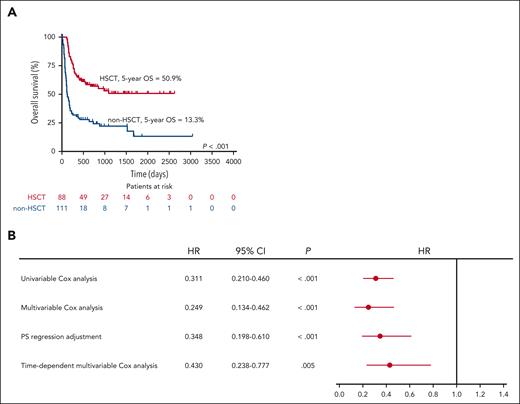

Validating the effectiveness of transplantation in the eligible cohort

Comparing the baseline data between the HSCT group and the non-HSCT group, there were no significant differences in sex, peripheral blood count, triglyceride, fibrinogen (FIB), FER, sCD25, and EBV-DNA copies. The incidence of hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and BM hemophagocytosis showed no differences. Patients in the non-HSCT group were older and had higher Cr (P < .05; Table 1). The median interval from diagnosis to HSCT was 83 days (26-1035). The 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates of HSCT group were 100.0%, 83.0%, 64.8%, 57.0%, 50.9%, and 50.9%, respectively. The median survival of non-HSCT group was 124 days (87-161), and the 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 83.1%, 38.1%, 30.7%, 26.2%, 22.1%, and 13.3%, respectively. HSCT improved the OS of patients (P < .001; Figure 3A).

Analysis of transplant effectiveness. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of non-HSCT and HSCT among patients eligible for transplant. (B) Forest plot showing the effect of transplantation on prognosis. PS, propensity score.

Analysis of transplant effectiveness. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of non-HSCT and HSCT among patients eligible for transplant. (B) Forest plot showing the effect of transplantation on prognosis. PS, propensity score.

Univariable Cox analysis showed that HSCT is a favorable prognostic factor of patients with EBV-HLH (hazard ratio [HR], 0.311; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.210-0.460; P < .001). In multivariable Cox analysis, the influence of sex, age, EBER, history of CAEBV, levels of white blood cells (WBCs), Hb, platelets, ALT, albumin (ALB), Cr, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), TG, FIB, β-2-microglobin (β2M), procalcitonin (PCT), FER, sCD25, and HSCT were analyzed. Correspondingly, the association between HSCT and superior OS was significant (HR, 0.249; 95% CI, 0.134-0.462; P < .001; supplemental Table 2). Propensity score was estimated by sex, age, EBER, history of CAEBV, levels of WBC, Hb, platelets, ALT, ALB, Cr, BUN, TG, Fbg, β2M, PCT, FER, and sCD25. Propensity score regression showed that HSCT is an independent positive prognostic factor of patients with EBV-HLH as well (HR, 0.348; 95% CI, 0.198-0.610; P < .001). Based on the median survival of non-HSCT group and median interval from diagnosis to HSCT, day 90 was selected as the cutoff point. Follow-up of patients was split into 2 observation intervals. The significant association was retained in the multivariable Cox analysis after adjusting (HR, 0.430; 95% CI, 0.238-0.777; P = .005; Figure 3B).

Outcomes of patients who underwent transplantation

As shown in Table 2, 48 patients (48/92 [52.2%]) in the HSCT cohort were alive at the last follow-up, with a mean survival time of 1343 days. At a median follow-up from transplantation of 980 days (49-2479), the 8-week, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 78.3%, 64.1%, 57.5%, 52.3%, 50.3%, and 50.3% among HSCT cohort, respectively. Overall, 44 patients died. Twenty-one died of HLH recurrence or progression, and 23 died of transplant-related complications, including GVHD (n = 11) and infection (n = 12). Details of death causes are summarized in supplemental Table 3. Patients who survived >6 months after transplantation have a relatively lower risk of death. The 5-year OS after HSCT for patients who obtained CR at HSCT was significantly higher than those with PR (61.3% vs 44.4%; P = .021; Figure 4A). The OS of patients who underwent HSCT at CR1 was not statistically different from those at PR1. There was also no difference between patients who received HSCT at CR1 and those at CR2 (P = .263; P = .156; Figure 4B). Notably, patients who received HSCT at CR1/PR1 had a significantly better prognosis than patients at PR2 (P = .001; P = .049; Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4C, patients with MC had an inferior OS compared with those with sustained FDC and those converted from MC to FDC (P = .002; P = .030). EBV infection to NK cells predominates over other lineages was associated with inferior outcomes (P = .002; Figure 4D). In univariable analysis, the CNS involvement (P = .210), conditioning regimen (P = .172), and donor type (P = .339) were not associated with the OS. Table 2 provides the univariable analysis results of other tested factors.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the HSCT patients. (A) OS by the HLH status at HSCT. (B) OS by the HLH status and timing of HSCT. (C) OS by the chimerism. (D) OS by the EBV-infected cell lineages.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the HSCT patients. (A) OS by the HLH status at HSCT. (B) OS by the HLH status and timing of HSCT. (C) OS by the chimerism. (D) OS by the EBV-infected cell lineages.

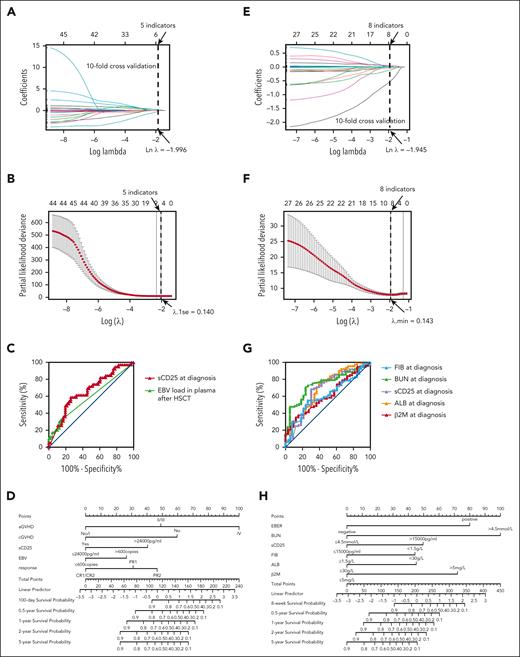

Prediction model for patients with HSCT built based on Lasso-Cox regression

Five indicators were obtained through Lasso regression when λ was 0.140 (the natural logarithm [Ln] of λ = –1.966; Figure 5A-B). The results of the Cox analysis are displayed in Table 3. The Cox regression model was further established based on sCD25, aGVHD, cGVHD, and EBV-DNA in plasma at 1 week after HSCT and HLH status at HSCT. When the cut-off value was 24 000 pg/mL for sCD25, 600 copies per mL for the post-HSCT EBV-DNA, the model showed excellent performance (Figure 5C). The Cox regression model was then turned into a nomogram (Figure 5D). The C-index of the model in the training set was 0.825 (95% CI, 0.795-0.856). The calibration curves of the model of 100, 180, and 300 days indicated good consistency between the predicted and observed results in both the training set and validation set (supplemental Figure 2A-F).

Prognostic risk models of patients with or without HSCT. (A) Reducing the effect of multicollinearity by compressing regression coefficients of variables in the model to 0 for patients undergoing HSCT. (B) The λ.1se was 1 standard error of λ, which corresponded to the smallest partial likelihood deviance of evaluation index for patients with HSCT. (C) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for sCD25 and EBV-DNA load of patients undergoing HSCT. (D) Nomogram used to predict time-related morality in patients with HSCT. (E) Reducing the effect of multicollinearity by compressing regression coefficients of variables in the model to 0 for patients without HSCT. (F) The λ.min corresponded to the smallest partial likelihood deviance of evaluation index for patients without HSCT. (G) ROC curves for indicators of patients without HSCT. (H) Nomogram used to predict time-related morality in patients without HSCT.

Prognostic risk models of patients with or without HSCT. (A) Reducing the effect of multicollinearity by compressing regression coefficients of variables in the model to 0 for patients undergoing HSCT. (B) The λ.1se was 1 standard error of λ, which corresponded to the smallest partial likelihood deviance of evaluation index for patients with HSCT. (C) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for sCD25 and EBV-DNA load of patients undergoing HSCT. (D) Nomogram used to predict time-related morality in patients with HSCT. (E) Reducing the effect of multicollinearity by compressing regression coefficients of variables in the model to 0 for patients without HSCT. (F) The λ.min corresponded to the smallest partial likelihood deviance of evaluation index for patients without HSCT. (G) ROC curves for indicators of patients without HSCT. (H) Nomogram used to predict time-related morality in patients without HSCT.

Prediction model for patients without HSCT built based on Lasso-Cox regression

Similarly, the prognosis of patients without HSCT was modeled using the methods described above. Variables screened by Lasso regression in Figure 5E and then crossvalidated were EBER, WBC, ALB, Cr, BUN, FIB, β2M, and sCD25 when λ was 0.143 (Ln λ = –1.945; Figure 4F). When sCD25 was 15 000 pg/mL, ALB was 30 g/L, FIB was 1.5 g/L, BUN was 4.5 mmol/L, and β2M was 5 mg/L; Figure 5G shows the most vital prognostic predictive value. The Cox regression model was then turned into a nomogram (Figure 5H) based on the above parameters (Table 4). The C-index of the model in the training set and validation set was 0.809 (95% CI, 0.781-0.838) and 0.688 (95% CI, 0.655-0.722), respectively. The calibration curves of the model built for predicting survival of 0.5, 1, and 2 years indicated good consistency between the predicted and observed results in both the training set and validation set (supplemental Figure 3A-F).

Discussion

HLH is an immunological aberrant activation syndrome with rapid progression and high mortality. The proposal of the HLH-94 protocol has remarkably improved the prognosis of HLH, with OS increasing from 5% to 54%.1 HSCT is regarded as a curative approach for HLH. In our previous studies, 5-year post-HSCT in adult patients with pHLH and lymphoma-associated HLH (LAHS) were 73% and 63%, respectively.15,16 Frustratingly, there is no consensus on transplantation for EBV-HLH. The risk of transplant-related death is considerable,17 and it is debatable whether such a risk is worth taking to treat EBV-HLH. A previous retrospective meta-analysis did not show the superiority of transplantation over immunochemotherapy in children with EBV-HLH.18 However, EBV reactivation and replication were commonly seen in patients with EBV-HLH, leading to a dismal prognosis.19 Reconstruction of the immune system through HSCT is a reliable way to prevent sustained viral replication. In this study, the 5-year OS of HSCT patients was 48.7%, which was remarkably higher than the 16.2% of patients who did not undergo transplant (P < .001). Among patients who achieved remission after immunochemotherapy, HSCT was associated with superior OS (P < .001) and lower relapse rate (P = .015). Our results suggest that transplantation does improve the prognosis of adult patients with EBV-HLH. The transplant-related mortality (TRM) in adult patients with EBV-HLH was 25%, which was comparable with data from adult pHLH, LAHS, and common hematologic malignancies.20,21 To further validate the prognostic impact of HSCT, we compared the OS of the HSCT group and the non-HSCT group in patients suitable for transplantation to reduce bias. Univariable analysis showed patients who received HSCT had superior survival. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that HSCT is an independent positive prognostic factor of adult patients with EBV-HLH. This significant association was retained in the multivariable Cox analysis after time adjusting.

Previous studies showed that HLH status at transplantation was associated with post-HSCT survival. Active HLH at transplantation was an adverse prognostic factor.22 In this study, 4 patients who received HSCT at active disease all died. Holistically, patients who achieved CR at transplantation had superior survival compared with patients with PR (HR, 0.467; 95% CI, 0.241-0.906; P = .024). More elaborate analyses show that there was no difference in OS between patients who received transplantation at CR1 and those at PR1 nor between patients at CR1 and CR2. However, patients who received transplantation at PR2 had inferior survival (P < .05). Among patients eligible for transplant, 60.6% of patients with CR1 achieved second remission, with a CR2 rate of 46.7%. Thus, for patients who achieved CR1, the opportunity to benefit from HSCT after second-line therapy remains high, and long-term survival would not be affected in nearly half of patients. Considering the treatment-related risk and the cost of HSCT, a wait-and-see strategy can be used. In contrast, only 20.4% of patients with PR1 achieved CR2, which is significantly lower than patients with CR1 (P = .014). Thus, HSCT was strongly recommended in patients with PR1. Regardless, obtaining remission before HSCT, preferably CR, is warranted. In a pediatric cohort, the response rate to the LDEP regimen was 61.5% in refractory EBV-HLH.23 The response rate to the DEP/LDEP regimen was >80%. These results suggest that the DEP/LDEP regimen is a promising treatment for EBV-HLH. Biological agents have offered alternative options for HLH treatment. Six relapsed/refractory adult patients with EBV-HLH treated with nivolumab monotherapy responded to treatment, with 5 remaining in CR for >40 weeks.24 Janus kinase protein inhibitors and interferon antibodies have been applied in the treatment of EBV-HLH as well.25,26

DLI/DSI is a practical approach in treating and preventing relapse after HSCT, as well as improving chimerism.27-29 In this study, 43 patients received DLI/DSI, and the effective rate was 30.2% (13/43). Our data indicated that patients with MC had a worse prognosis than those with FDC (P < .001). Although chimerism stabilization at 10% to 20% is adequate to prevent disease recurrence in patients with pHLH,30 it is evident that MC is insufficient for patients with EBV-HLH. MC was more common in patients with EBV infection to NK cells (along or dominantly) (P = .03). For this group of patients, intensive monitoring of the chimerism and more vigorous DLI/DSI therapy may be beneficial. Unfortunately, patients with FDC might suffer HLH relapse as well. A recent study found that the portion of EBV-positive cells could be relatively low in patients with EBV-HLH.31 This might explain the recurrence of HLH among patients retained FDC. Apart from relapse and graft failure, the leading causes of TRM in this study were aGVHD and infection, with the former occurring predominantly in the early stages after transplantation and the latter throughout the entire posttransplant period. Alloreactive T cells mediate beneficial graft vs disease effects and deleterious GVHD.32 In various studies,33,34 the occurrence of cGVHD has been linked to a lower relapse rate, leading to improved prognosis. A similar result was obtained in our study. Development of cGVHD is a favorable prognostic factor (HR, 0.432; 95% CI, 0.219-0.851; P = .015).

Our results showed that post-HSCT EBV-DNA load exceeding 600 copies per mL in plasma has a negative impact on survival after HSCT (HR, 2.150; 95% CI, 1.010-4.575; P = .047). Lytic replication of EBV typically results in cell death and the release of infectious viruses.35 Hence, an elevated plasma EBV load may indicate active viral replication, resulting in a poor prognosis. In the study by Yanagaisawa et al, it was found that patients with high EBV-DNA load in plasma were more predisposed to HLH recurrence.36 Intensive monitoring of the EBV-DNA load after HSCT is necessary. Therefore, quantitative detection of EBV is more recommended than serological assays.37 For patients with posttransplant viral reactivation, rituximab, immunosuppressant dose decrease, and EBV-cytotoxic T lymphocyte infusion should be considered.38 A high level of sCD25 represents a negative prognostic factor in both transplant (HR, 3.221; 95% CI, 1.559-6.654; P = .002) and nontransplant patients (HR, 2.086; 95% CI, 1.073-4.058; P = .030). sCD25 is an indicator of T-cell activation.39 The correlation between sCD25 and prognosis is not surprising given the critical role of the excessive T-cell activation in HLH.40 In nontransplant patients, patients with EBV infection restricted to B cells had significantly superior survival compared with others (P = .010), which may be attributed to the depletion of B cells by anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.5 Unfortunately, patients with EBV infection to T or NK cells have a dismal prognosis, particularly for those with NK cells. A recent study showed that EBV-positive NK cells could secrete abundant IFN-γ, thereby promoting differentiation of monocytes to macrophages and enhancing the procoagulant activity of monocytes. This phenomenon was less pronounced in EBV-positive T cells. That may account for the worse prognosis of patients with EBV infection to NK cells.41,42 Our results showed that HSCT overcomes the detrimental prognostic effects of the persistence of EBV-positive T/NK cells. Thus, for patients with EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment, HSCT was recommended.

This study followed, to our knowledge, the largest cohort of 356 adult patients with EBV-HLH. Our data demonstrated that HSCT improved the survival of adult EBV-HLH significantly. For patients who achieved PR after initial treatment, HSCT was strongly recommended. A wait-and-see strategy could be adopted for patients who achieved CR after initial treatment but with the risk of failing to achieve CR2. HSCT was recommended for patients with EBV-positive T/NK cells at 8 weeks after initial treatment. The prognostic prediction models established in this study might help the treatment decision-making in adult patients with EBV-HLH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhao Wang, Jingshi Wang, Lin Wu, and Na Wei for the work of transplantation and the attentive care of patients. The authors are grateful to Shanshan Wu for her assistance with the statistical design.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 82170122).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.W. designed the research; S.Y., L.H., D.S., H.Z., Y.Z., and Y.W. analyzed and interpreted the data; S.Y. and L.H. wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation of Y.W. is Department of Hematology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Correspondence: Yini Wang, Department of Hematology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Anzhen Rd, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China; email: wangyini@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

Author notes

S.Y. and L.H. contributed equally as first authors to this study.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Yini Wang (wangyini@ccmu.edu.cn).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.