Key Points

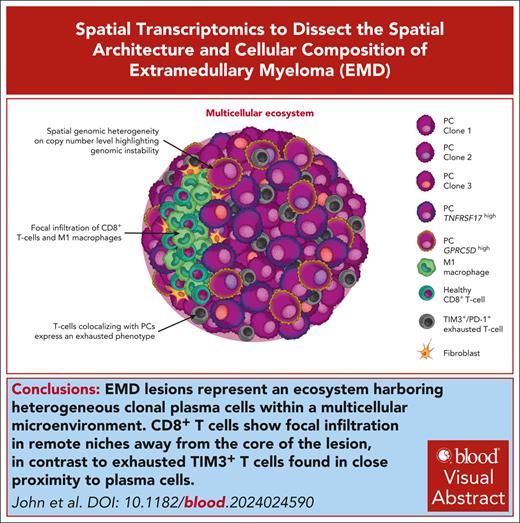

EMD mimics the architectural complexity of solid tumors, marked by diverse microenvironments, multiclonality, and TNFRSF17 and GPRC5D levels.

EMD shows infiltration of active T cells spatially confined to niches segregated from MM cells, potentially affecting the therapeutic response.

Visual Abstract

Extramedullary disease (EMD) is a high-risk feature of multiple myeloma (MM) and remains a poor prognostic factor, even in the era of novel immunotherapies. Here, we applied spatial transcriptomics (RNA tomography for spatially resolved transcriptomics [tomo-seq] [n = 2] and 10x Visium [n = 12]) and single-cell RNA sequencing (n = 3) to a set of 14 EMD biopsies to dissect the 3-dimensional architecture of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Overall, infiltrating immune and stromal cells showed both intrapatient and interpatient variations, with no uniform distribution over the lesion. We observed substantial heterogeneity at the copy number level within plasma cells, including the emergence of new subclones in circumscribed areas of the tumor, which is consistent with genomic instability. We further identified the spatial expression differences between GPRC5D and TNFRSF17, 2 important antigens for bispecific antibody therapy. EMD masses were infiltrated by various immune cells, including T cells. Notably, exhausted TIM3+/PD-1+ T cells diffusely colocalized with MM cells, whereas functional and activated CD8+ T cells showed a focal infiltration pattern along with M1 macrophages in tumor-free regions. This segregation of fit and exhausted T cells was resolved in the case of response to T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies. MM and microenvironment cells were embedded in a complex network that influenced immune activation and angiogenesis, and oxidative phosphorylation represented the major metabolic program within EMD lesions. In summary, spatial transcriptomics has revealed a multicellular ecosystem in EMD with checkpoint inhibition and dual targeting as potential new therapeutic avenues.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is considered the paradigm of a tumor in its microenvironment because the survival of MM cells is largely confined to the plasma cell (PC) survival niche, a microanatomical area located along the capillaries of the bone marrow (BM).1,2 Outside this niche, both malignant and healthy PCs are subject to apoptosis. Extramedullary disease (EMD), which refers to the presence of plasmacytomas outside of the BM, challenges this paradigm. Approximately 6% of patients with MM have EMD lesions at diagnosis, and up to 30% develop them during the disease.3-6 Although patients with intramedullary myeloma have benefited greatly from recent advances in immunotherapy, the response rates to chimeric antigen receptor T cells, monoclonal antibodies, and bispecific antibodies are ∼50% lower in patients with EMD for reasons that are not yet understood.5,7-10 In the absence of an optimal treatment or follow-up strategy, EMD has emerged as a key challenge in relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting in MM.5,11-13

Knowledge of the biological mechanisms underlying extramedullary spread is limited. We and others have previously shown that the genomic profiles of EMD are distinct from those of diffuse BM infiltration.14 We have identified highly aggressive subclones that exhibit biallelic inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, including TP53, and increased proliferation in focal lesions,15 aiding in the explanation of its poor prognostic impact. Recent studies on solid cancer have uncovered complex ecosystems in primary tumors and their metastases that influence immune cell fitness and metabolic programs.16-18 Solid tumors often exhibit distinct “hot” and “cold” regions, characterized by high and low T-cell infiltrates, respectively.19-21 This suggests that dysfunctional T-cell phenotypes can be localized spatially within the tumor.19 However, in EMD, it is commonly believed that lesions comprise only sheets of PCs.

To shed light on the spatial organization of MM and immune cells in EMD, we applied spatial transcriptomics (ST) using RNA tomography for spatially resolved transcriptomics (tomo-seq), 10x Visium, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on a set of biopsies from patients with R/RMM. We show substantial tumor heterogeneity and spatial variation in the distribution of exhausted T cells within EMD lesions, which may be related to the decreased response rate to novel immunotherapies, as shown in 2 case studies.

Methods

Patients and sample preparation

This study was approved by the internal review board of the University of Würzburg (Germany, reference nos. 8/21 and 151/19-sc) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki of 2008. All patients gave their written informed consent.

Extramedullary lesion punch biopsies were taken at the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) or frozen in a CryoStor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Tissue staining

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed. CD3e, CD11b, CD31, CD138, and collagen I protein expression was determined by immunofluorescence (IF) staining.

tomo-seq

The EMD from PT01A was cut in half. One-half was used for tomo-seq and the other half was used for H&E staining and 10x Visium ST. Sections for tomo-seq were at a 90° angle for H&E staining. Sections 1 to 3 are 2 sections combined with each 20 μm section with 120 μm distance. From section 4 on, 30 μm sections were used with a 60 μm distance to the next section. For PT10A, 40 μm sections were used, and between sections were 80 μm distance. RNA was isolated from each section, and 30 ng of RNA was used as input in the NEBNext Single Cell/Low Input RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany). Libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol, pooled, and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq2000.

10x Visium ST

Approximately 10 μm sections of the EMDs were placed on 10x Visium Spatial Gene Expression slides for fresh-frozen tissues and processed following the manufacturer’s protocol (Visium Spatial Gene Expression Reagent Kits, CG000239, 10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA). Pooled libraries were sequenced using an Illumina NextSeq2000.

scRNA-seq

Tissues were digested into single cells and viability staining was performed. Cells were blocked and stained with extracellular (CD3e, CD38, CD138, CD140a, CD140b, and podoplanin) and hash-tagged antibodies (TotalSeq-B0251-B0254). Cells were sorted for viable cells (FACS Aria III, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). A total of 20 000 cells were loaded onto the 10x controller and library preparation was performed following the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit v3.1 (Dual Index). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq2000.

WGS

For whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of PT08 and PT10, 1 punch biopsy was snap-frozen. WGS was performed as described earlier.22

Bioinformatic and statistical analyses

tomo-seq analysis

The quality of the FASTQ files was evaluated using FASTQC, resulting in the removal of section 29.23 Reads were aligned to the human genome (Ensembl Release 105) using STAR, and expression levels were quantified using FeatureCounts and normalized to transcripts per million.24 Analysis using the tomoda R package25 encompassed Pearson correlation, uniform manifold approximation projection, and identification of spatially upregulated genes. Immune and stromal gene set enrichment analysis scores were calculated using estimation of stromal and immune cells in malignant tumor tissues using expression data (ESTIMATE).26 Cell type proportions were estimated using mean expression profiles from Blueprint and Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data, integrated with a signature matrix created in the Deconvolution Model Comparison (DMC) R package.27-29 Both were processed using CIBERSORT implementation in the immunedeconv R package.30,31

scRNA-seq analysis

Cell Ranger 7.0.0 mapped libraries to GRCh38 (GENCODE v32/Ensembl 98).32 Quality control removed cells with <200 and >10% mitochondrial genes, and DoubletFinder was used to remove doublet cells.33 The analysis was conducted using Seurat 4.3.0 according to the recommended workflow,34 including normalization, log transformation, identification of the top 2000 variable features (“vst”), and uniform manifold approximation projection embedding using 30 principal components. Harmony-corrected batch effects between the samples. The cell types were assigned via canonical markers identified using FindAllMarkers.34,35 The top 100 upregulated genes per cell type were subjected to pathway enrichment analysis using ClusterProfiler.36 scCustomize was used for visualization.37

10x Visium ST analysis

The libraries were processed using Space Ranger 1.1.0.32 GRCh38 was used as the reference genome. Loupe Browser 6 aided in identifying tissue-covered spots using IF images and Visium slides. Seurat 4.3.0 was used with certain quality control parameters (spots with >300 reads or >20% mitochondrial genes). Cell2location uses publicly available single-cell data from human lymph nodes, spleen, and tonsils to estimate cell type abundances per spot using a negative binomial regression model. The untransformed and unnormalized messenger RNA counts of selected genes were used to quantify cell abundance after excluding mitochondrial genes.38,39

Inferring spatial CNVs

The gene expression matrixes were processed using InferCNV.40 Immune cells from our scRNA-seq data set served as reference. Genes expressed in <3 spots were removed. After normalization, log transformation, and centering of gene expression across normal cells, copy number variations (CNVs) were summarized into cytogenetic regions via mean residual expression intensities. The Hidden Markov model classified CNVs into 6 states. In silico spike-ins were generated based on the normal cell properties for calibration. The Bayesian latent mixture model was used to determine the posterior probabilities of the states in each cell and region. Predictions were visualized using PlotCNV.41

Results

Patients’ characteristics

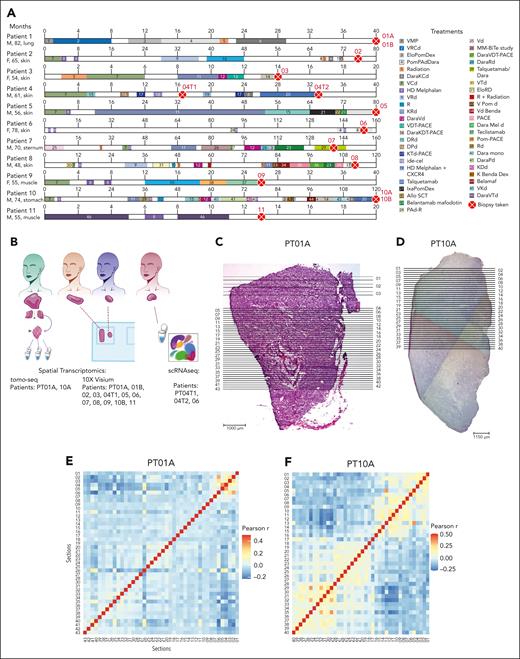

To investigate the spatial architecture of EMD, we analyzed 14 biopsies from 11 patients (7 males and 4 females) with a median age of 61 years (age range, 48-82; Figure 1A). Patients were heavily pretreated with a median number of 8 prior lines of therapy (range 2-18). Four patients underwent biopsy while being treated with the bispecific T-cell redirecting antibody, teclistamab or talquetamab. Samples were divided for ST, either tomo-seq and/or 10x Visium, and scRNA-seq (Figure 1B).

Methodological overview and tomo-seq highlights spatial heterogeneity in 2 whole-tumor lesions. (A) Graphical representation of the patients’ clinical information. Each horizontal line represents a patient. The timeline is segmented and colored according to the duration and treatment agent. The red dot with a cross represents the time at which the biopsies were collected. (B) A scheme illustrating the methods used. (C-D) Longitudinal H&E images of the whole lesion of PT01A (C) and PT10A (D). The horizontal lines represent the approximate locations of the sections used for the tomo-seq. (E-F) Pearson correlation coefficients between every pair of sections calculated using the whole transcriptome profiles for PT01A (E) and PT10A (F). (G-H) Inferred cell type fractions for all sections for PT01A (G) and PT10A (H) generated using CIBERSORT and a reference of RNA sequencing data of pure stroma and immune cell types retrieved from Blueprint and ENCODE. (Gi,Hi) The panel represents all detected cell types, including PCs. (Gii,Hii) Representative fractions of cell types, excluding PCs. (I-J) Normalized counts of GPRC5D and TNFRSF17 in PT01A (I) and PT10A (J). (K) Circos plot of WGS of PT10. A, AraC; Allo SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; B, BCNU; Benda, bendamustine; C, cyclophosphamide; C in PACE, cisplatine; D, doxorubicine; Dara, daratumumab; d/Dex, dexamethasone; E, etoposide; Elo, elotuzumab; F, female; HD, high dose; ide-cel, idecaptagene vicleucel; Ixa, ixazomib; K, carfilzomib; M, male; M/Mel, melphalan; P, prednisone; Pom, pomladomide; R, lenalidomide; T, thalidomide; V, bortezomib.

Methodological overview and tomo-seq highlights spatial heterogeneity in 2 whole-tumor lesions. (A) Graphical representation of the patients’ clinical information. Each horizontal line represents a patient. The timeline is segmented and colored according to the duration and treatment agent. The red dot with a cross represents the time at which the biopsies were collected. (B) A scheme illustrating the methods used. (C-D) Longitudinal H&E images of the whole lesion of PT01A (C) and PT10A (D). The horizontal lines represent the approximate locations of the sections used for the tomo-seq. (E-F) Pearson correlation coefficients between every pair of sections calculated using the whole transcriptome profiles for PT01A (E) and PT10A (F). (G-H) Inferred cell type fractions for all sections for PT01A (G) and PT10A (H) generated using CIBERSORT and a reference of RNA sequencing data of pure stroma and immune cell types retrieved from Blueprint and ENCODE. (Gi,Hi) The panel represents all detected cell types, including PCs. (Gii,Hii) Representative fractions of cell types, excluding PCs. (I-J) Normalized counts of GPRC5D and TNFRSF17 in PT01A (I) and PT10A (J). (K) Circos plot of WGS of PT10. A, AraC; Allo SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; B, BCNU; Benda, bendamustine; C, cyclophosphamide; C in PACE, cisplatine; D, doxorubicine; Dara, daratumumab; d/Dex, dexamethasone; E, etoposide; Elo, elotuzumab; F, female; HD, high dose; ide-cel, idecaptagene vicleucel; Ixa, ixazomib; K, carfilzomib; M, male; M/Mel, melphalan; P, prednisone; Pom, pomladomide; R, lenalidomide; T, thalidomide; V, bortezomib.

ST reveals diverse cellular niches within EMD lesions

Extramedullary plasmacytoma lumps may measure several centimeters in all dimensions. To gain insight into the overall cell type architecture, we performed tomo-seq42 on 2 whole EMD samples surgically removed from patients 1 and 10 (PT01A and PT10A). The sample was cut in half, with the horizontal cut used for H&E staining and the vertical cut used for tomo-seq. The tissue was cut into 43 (PT01A) or 40 (PT10A) sections and bulk RNA sequencing was performed on each section (Figure 1C-D).

We observed high intersectional heterogeneity, as shown by the Pearson correlation coefficients calculated between each pair of sections (Figure 1E-F). Although most sections for PT01A were transcriptionally heterogeneous, the transcriptomes of sections 1 to 6 were more similar to each other, with the highest correlation compared with other sections (Figure 1E). The EMD lesions of PT10A showed clusters of sections with similar expression profiles (sections 1-4, 7-16, 18-27, 28-37, and 38-40; Figure 1F). We calculated scores for immune and stromal cells in each section using the ESTIMATE R package.26 These cell types were predicted to be enriched in sections 1 to 6 and sections 22 to 28 (PT01A; supplemental Figure 1A-B, available on the Blood website) and sections 6 to 15 and 14 to 28, respectively (PT10A; supplemental Figure 1C-D). We further used CIBERSORT with Blueprint and ENCODE as references.27,28,30 As expected, PCs were the predominant cell type in all sections from both patients ranging, from 59.3% to 91.6% (Figure 1G-H). For the PT01A EMD lesion, immune cells, including CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and dendritic cells (DCs), were also predicted to be enriched (Figure 1Gi-ii), whereas for the EMD lesion of PT10A, endothelial cells and regulatory T cells were observed (Figure 1Hi-ii). The range of cell types varied between every section (supplemental Table 1). In the first 6 sections of the EMD lesion of PT01A, we found an enrichment of immune and stromal pathways corresponding to the immune and stromal scores (supplemental Figure 1E), whereas, in the EMD lesion of PT10A, stromal pathways were enriched in sections 1 to 15 (supplemental Figure 1F). Our approach revealed a multicellular network within the EMDs and identified a spatial organization of immune and stromal cells clustering in specific regions.

Intratumor heterogeneity in the expression levels of BCMA and GPRC5D

We asked whether the expression levels of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) and GPRC5D, 2 major antigens in MM immunotherapy, were homogeneous across EMD sections. GPRC5D and TNFRSF17 (BCMA) showed profound expression differences throughout the lesions, especially in PT01A, which may be clinically relevant (Figure 1I). PT10A, who was treated with talquetamab before biopsy, showed more homogenous expression of TNFRSF17 and no expression of GPRC5D (Figure 1J), and WGS displayed loss of 1 GPRC5D allele (Figure 1K; supplemental Figure 6K). This was different from the derived PC fractions, which were constant across all sections, suggesting relevant clonal heterogeneity for these PC antigens.

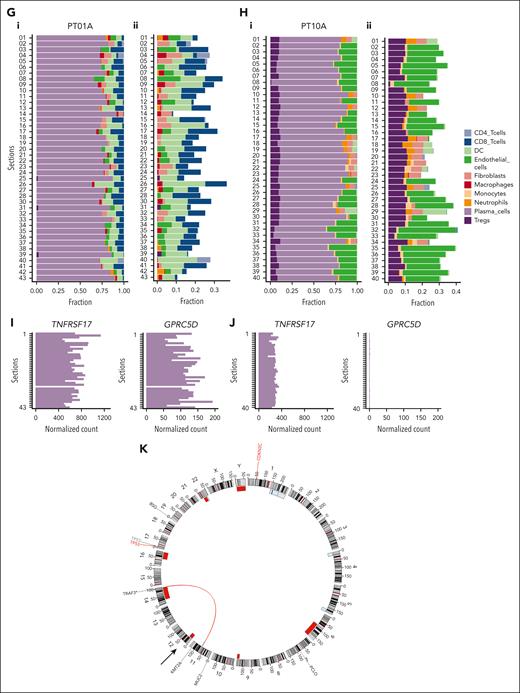

Fit and exhausted T cells localize to distinct niches within EMD lesions

Although tomo-seq provided a high-level overview of the transcriptomic architecture in EMD, we next investigated the spatial cellular composition at a closer level. Because tomo-seq revealed an abundance of T cells within EMD lesions, we wanted to confirm this finding using IF and immunohistochemistry. Here, 7 of 9 biopsies (PT01A and B, PT03, PT07, PT08, PT11, and PT10B) showed T-cell infiltration, whereas 2 of 9 (PT02 and PT09) were found to be T-cell depleted (Figure 2; supplemental Table 2). In T-cell–infiltrated lesions, T cells were found near PCs and stromal cells (Figure 2A), inside and outside blood vessels (Figure 2B), and in areas with varying myeloid cell content (Figure 2C).

T-cell infiltration of EMD lesions. Representative IF of T-cell–infiltrated and T-cell–depleted EMDs. (A) IF of PT01B (left), PT03 (center), and PT02 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, red), and collagen (α-Collagen I, blue). (B) IF of PT11 (left) and PT09 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, blue), and endothelium (α-CD31, red). (C) IF of PT10B (left) and PT09 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, blue), and myeloid cells (α-CD11b, red). Scale bars 500 μm. Inlay scale bars 100 μm.

T-cell infiltration of EMD lesions. Representative IF of T-cell–infiltrated and T-cell–depleted EMDs. (A) IF of PT01B (left), PT03 (center), and PT02 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, red), and collagen (α-Collagen I, blue). (B) IF of PT11 (left) and PT09 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, blue), and endothelium (α-CD31, red). (C) IF of PT10B (left) and PT09 (right) for markers of T cells (α-CD3e, green), PCs (α-CD138, blue), and myeloid cells (α-CD11b, red). Scale bars 500 μm. Inlay scale bars 100 μm.

We then used an untargeted microarray-based ST approach (10x Visium) and processed 12 EMD biopsies from 11 patients. Nine samples met our stringent quality control criteria (reads >300 and mitochondrial genes <20%) and were used for further analysis (supplemental Figure 2A-H). We used the Leiden algorithm to cluster cell type abundances, identifying tissue regions for each sample (Figure 3A).43 To deconvolute cell types, we used cell2location and an annotated scRNA-seq data set of human secondary lymphoid organs (supplemental Figure 2I).38 In agreement with the IF and immunohistochemistry analysis, this analysis confirmed that PT02 and PT09 were T-cell depleted (supplemental Table 2).

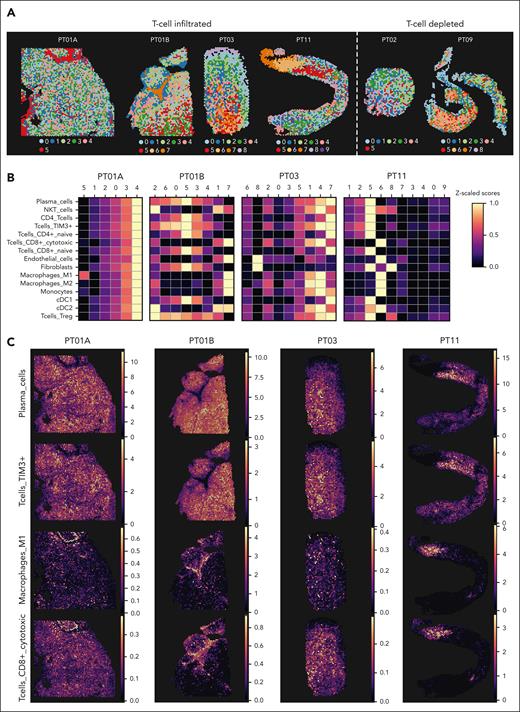

Focal infiltration of immune cells in EMD lesions. (A) Clusters generated using the Leiden algorithm based on estimated cell type abundances calculated from cell type deconvolution using cell2location of ST data of samples taken from PT01A, PT01B, PT03, and PT11 for T-cell–infiltrated lesions and PT02 and PT09 for T-cell depleted lesions. (B) Heat map showing the scaled z score of estimated cell abundance of cell types across Leiden clusters shown in panel A for T-cell–infiltrated lesions (PT01A, PT01B, PT03, and PT11). (C) Estimated spatial cell type abundances of PCs, T-cells Tim3+, M1 macrophages, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells across samples, as in panel B.

Focal infiltration of immune cells in EMD lesions. (A) Clusters generated using the Leiden algorithm based on estimated cell type abundances calculated from cell type deconvolution using cell2location of ST data of samples taken from PT01A, PT01B, PT03, and PT11 for T-cell–infiltrated lesions and PT02 and PT09 for T-cell depleted lesions. (B) Heat map showing the scaled z score of estimated cell abundance of cell types across Leiden clusters shown in panel A for T-cell–infiltrated lesions (PT01A, PT01B, PT03, and PT11). (C) Estimated spatial cell type abundances of PCs, T-cells Tim3+, M1 macrophages, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells across samples, as in panel B.

Focusing on the T-cell–infiltrated EMD lesions (PT01A, PT01B, PT03, and PT11), we indeed observed different cell types within the clustered spots of each lesion, supporting the tomo-seq analysis (Figure 3B). Although PCs were the predominant cell type in all samples (median, 3.2 ± 2.71 cell type abundance; supplemental Figure 2J; supplemental Table 3), our approach uncovered microanatomical niches populated by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, endothelial cells, and formally known as M1 macrophages in otherwise PC-free regions in PT01B, PT03, and PT11 (clusters 7, 4, and 6, respectively; Figure 3B). Spatial deconvolution confirmed that PCs were distributed throughout the sample area, whereas M1 macrophages and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells clustered in distinct niches (Figure 3C). In contrast, T cells expressing high levels of genes related to T-cell exhaustion and dysfunction, TIM3+/PD-1+ T cells, colocalized with PCs, highlighting the spatial distance between fit and exhausted immune cells (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 2K). Our data revealed that EMD lesions are infiltrated by several types of immune cells that are anatomically confined to distinct niches. Remarkably, functional cytotoxic T cells appeared to be excluded from PC areas, whereas T cells found in the vicinity of PCs showed signs of T-cell dysfunction. We went on to explore the biological mechanisms underlying the separation of fit and exhausted T cells. Focusing on the patient sample PT01B (surgically removed lesion of considerable size), we found enrichment of the hallmarks of angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the areas of fit T cells. Areas with high PC abundance were enriched for proliferation-related signatures, and at the metabolic level, were enriched for an oxidative phosphorylation signature (supplemental Figure 3A).

In situ activation via CD2-CD58 interactions has been shown to be critical for T-cell entry into MM nodules.44 Cell type deconvolution showed that cDC1s deprived of CD58 expression were found in PC-rich niches. cDC2s with high CD58 expression were found in remote niches similar to cytotoxic T cells, supporting these data and strengthening a possible defect in the ability of active T cells to infiltrate the EMD mass (supplemental Figure 2K; supplemental Figure 3B).

In summary, our data support a distinct metabolic program and potential vascular content at the interface between M1 macrophages, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and tumor cells.

Clonal and subclonal CNVs highlight differences within and between patients

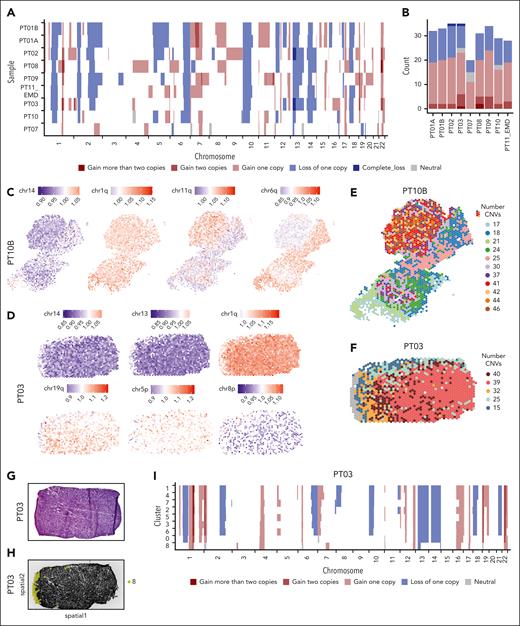

CNVs are a hallmark of MM. Our untargeted spatial approach allowed us to predict CNVs in MM using a Hidden Markov model. We inferred CNVs from messenger RNA data in all 9 EMD lesions using a pipeline validated by previous studies45,46 (Figure 4A; supplemental Figures 4A-J and 6D-I; supplemental Table 4).

Clonal and subclonal CNVs highlight the spatial variation. (A) Hidden Markov Model (HMM)-based CNVs prediction depicting the state of CNVs (complete loss, loss of 1 copy, neutral, gain of 1 copy, gain of 2 copies, and gain of >2 copies) in regions across all 22 chromosomes. Each row represents a patient and each column represents a chromosome. The samples were ordered according to the number of CNV predicted with the patient with the highest number at the top. (B) The total number of predicted CNVs in each patient, color-coded, as in panel A. (C-D) Per spot mean residual expression values of all detected genes across a chromosome or chromosome arm in the ST sample of PT10B (C) and PT03 (D), respectively. The gain in the CNVs is represented in red and the loss is represented in blue. (E) The total number of predicted CNVs for each spot of PT10B. (F) The total number of predicted CNVs for each spot for PT03. (G) H&E staining of the punch biopsy from PT03. (H) Black and white images of punch biopsy of PT03 used for ST. Spots belonging to cluster 8 (normal skin) are highlighted. (I) HMM-based CNVs prediction of the ST Leiden clustering of the sample obtained from PT03, in which each row represents a cluster identified.

Clonal and subclonal CNVs highlight the spatial variation. (A) Hidden Markov Model (HMM)-based CNVs prediction depicting the state of CNVs (complete loss, loss of 1 copy, neutral, gain of 1 copy, gain of 2 copies, and gain of >2 copies) in regions across all 22 chromosomes. Each row represents a patient and each column represents a chromosome. The samples were ordered according to the number of CNV predicted with the patient with the highest number at the top. (B) The total number of predicted CNVs in each patient, color-coded, as in panel A. (C-D) Per spot mean residual expression values of all detected genes across a chromosome or chromosome arm in the ST sample of PT10B (C) and PT03 (D), respectively. The gain in the CNVs is represented in red and the loss is represented in blue. (E) The total number of predicted CNVs for each spot of PT10B. (F) The total number of predicted CNVs for each spot for PT03. (G) H&E staining of the punch biopsy from PT03. (H) Black and white images of punch biopsy of PT03 used for ST. Spots belonging to cluster 8 (normal skin) are highlighted. (I) HMM-based CNVs prediction of the ST Leiden clustering of the sample obtained from PT03, in which each row represents a cluster identified.

More than 35 CNVs were identified, with more gains than deletions (Figure 4B). Known MM aberrations included amp(1q) in patients PT02, PT03, PT08, and PT09 and clonal del(13q) in patients PT02 and PT03 (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 4E,G).6,11 Some CNVs were clonal, such as chr14, and chr1q for PT10B and PT03 and chr13 for PT03 (Figure 4C-D), with most spots showing either gain (red) or loss (blue), others were subclonal and restricted to a limited number of spots, such as chr11q for both PT03 and PT10B, chr6q for PT10B and finally, chr5p, and chr8p for PT03 (Figure 4C-D). An intriguing snapshot of genomic instability was identified in PT03 and PT10B. In PT10B, 11 distinct clusters of spots with varying CNV counts and spatial locations were identified, notably clusters 2, 8, 10, and 5, which had 30, 42, 44, and 46 CNVs, respectively (Figures 4E). PT03 had 6 clusters with different CNV numbers and fewer aberrations near normal tissue. This highlighted the genomic instability present in spatially distinct areas of the lesion (Figure 4F). Inferring CNVs from gene expression data is challenging because of the noisy nature of read count data.47 Therefore, we performed validation approaches to confirm our findings. The biopsy from PT03 contained skin tissue, which we used as a negative control (Figure 4G). Indeed, cluster 8, which was specific to the skin, showed only a few CNVs (Figure 4H-I). Furthermore, a diagnostic set of fluorescence in situ hybridization probes from iliac crest biopsies was available in 3 patients and confirmed the clonal events seen in our analysis (supplemental Table 5). Last, WGS data of the PT08 EMD lesion were available, and we confirmed the losses and gains predicted by us (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 6J; supplemental Table 6).

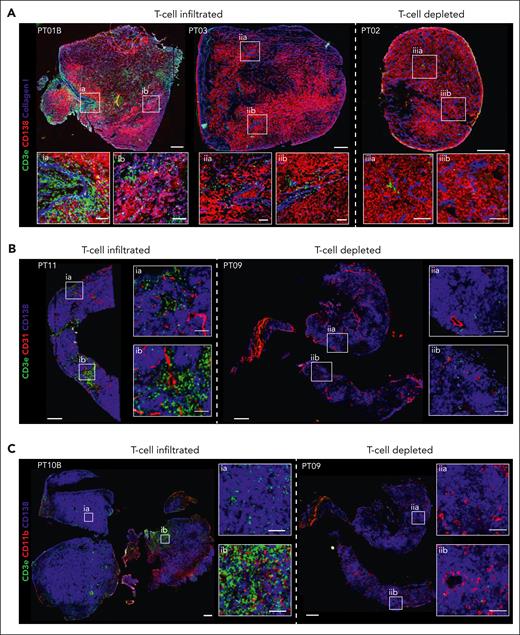

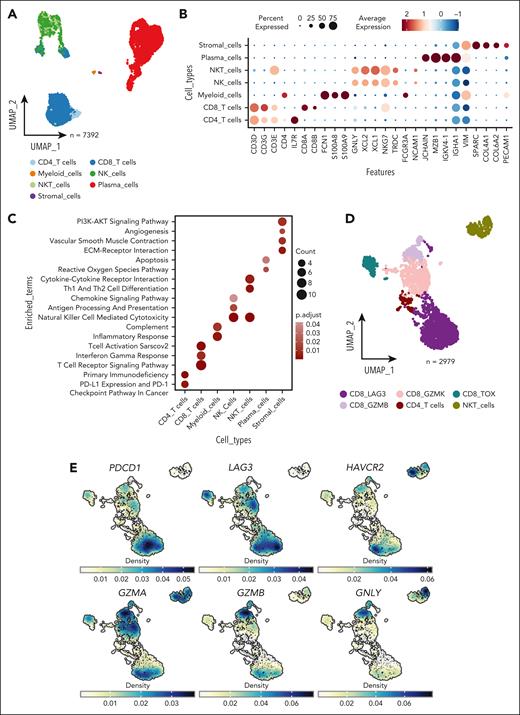

scRNA-seq reveals the cellular constituents of the microenvironment of EMDs. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot calculated using the top 30 principal component analysis (PCA) components identified after batch correction for samples showing annotated cell types. (B) Normalized expression of marker genes used to annotate cell types. (C) Enriched pathways of each cell type, cross-referencing Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), MSigDB hallmarks, and WikiPathways databases with the top 50 upregulated genes for each cell type. (D) UMAP visualization depicting the annotated subclusters of T cells. (E) Density plot illustrating the expression of genes associated with T-cell dysfunction (PDCD1, LAG3, and HAVCR2) and T-cell function (GZMA, GZMB, and GNLY). NK, natural killer cells; NKT, natural killer T cells.

scRNA-seq reveals the cellular constituents of the microenvironment of EMDs. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot calculated using the top 30 principal component analysis (PCA) components identified after batch correction for samples showing annotated cell types. (B) Normalized expression of marker genes used to annotate cell types. (C) Enriched pathways of each cell type, cross-referencing Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), MSigDB hallmarks, and WikiPathways databases with the top 50 upregulated genes for each cell type. (D) UMAP visualization depicting the annotated subclusters of T cells. (E) Density plot illustrating the expression of genes associated with T-cell dysfunction (PDCD1, LAG3, and HAVCR2) and T-cell function (GZMA, GZMB, and GNLY). NK, natural killer cells; NKT, natural killer T cells.

ST reveals microenvironmental differences between therapy-responsive and therapy-resistant patients. (A-C) Leiden clustering of spots based on the cell type abundances for PT07 (A), PT08 (B), and PT10B (C). (D) Maximum-intensity projection (MIP) and transaxial [18F] fluorodesoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography. The leftmost panels show PT07 at baseline and multiple lesions on both sides are indicated by arrowheads. In the middle panel, after talquetamab treatment, a follow-up scan was conducted 14 months later. A punch biopsy was taken from the lesion indicated by the circle. The rightmost panels display a follow-up scan after 20 months. Arrows indicate location of biopsied lesion. (E-G) Cell type abundances of PCs, macrophages M1, CD8+ T cytotoxic, and T-cells Tim3+ for PT07 (E), PT08 (F), and PT10B (G). (H) Cell type abundance comparing PCs, macrophages M1, and T-cells Tim3+ in all patients. Pairwise comparisons were implemented using the Wilcoxon test; ∗∗∗P < .001.

ST reveals microenvironmental differences between therapy-responsive and therapy-resistant patients. (A-C) Leiden clustering of spots based on the cell type abundances for PT07 (A), PT08 (B), and PT10B (C). (D) Maximum-intensity projection (MIP) and transaxial [18F] fluorodesoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography. The leftmost panels show PT07 at baseline and multiple lesions on both sides are indicated by arrowheads. In the middle panel, after talquetamab treatment, a follow-up scan was conducted 14 months later. A punch biopsy was taken from the lesion indicated by the circle. The rightmost panels display a follow-up scan after 20 months. Arrows indicate location of biopsied lesion. (E-G) Cell type abundances of PCs, macrophages M1, CD8+ T cytotoxic, and T-cells Tim3+ for PT07 (E), PT08 (F), and PT10B (G). (H) Cell type abundance comparing PCs, macrophages M1, and T-cells Tim3+ in all patients. Pairwise comparisons were implemented using the Wilcoxon test; ∗∗∗P < .001.

In summary, we have shown profound spatial genomic heterogeneity at the micrometer scale in EMD, highlighting genomic instability and the ability of ST to capture these alterations.

EMD microenvironments reveal the coexistence of dysfunctional and cytotoxic CD8 T cells

To investigate the supporting microenvironment, we performed scRNA-seq on 3 punch biopsies (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 5A) excluding malignant cells (identified as CD138 and CD38 negative). After quality control, 7392 cells were further analyzed and annotated using canonical markers for T, myeloid, natural killer, stromal, and plasma cells (Figure 5A-B). To functionally characterize the EMD microenvironment, over-representation analyses were conducted using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), MSigDB hallmarks, and WikiPathways (Figure 5C). Here, CD8 T, natural killer T cells, myeloid, and natural killer cells were enriched in pathways related to the activation of immune function, confirming our previous observation of an activated subpopulation of T cells. However, it was unclear whether these cells infiltrated the tumor due to the loss of spatial information resulting from tissue dissociation. Increased vessel density is a hallmark of EMD,48-50 and stromal cells showed enrichment of pathways related to angiogenesis.

Among EMDs, most T cells were CD8 T cells. After clustering and annotation of the T cells (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 5B), we identified a CD8 T-cell cluster with the expression of T-cell dysfunction markers (HAVCR2 (TIM3), LAG3, and PDCD1; Figure 5D-E) and another cluster expressing genes associated with T-cell cytotoxicity (GZMA, GZMB, and GNLY). We confirmed this finding by examining T cells from an external data set of 5 EMD samples. (supplemental Figure 5C-D).51

Our results support the coexistence of both dysfunctional and cytotoxic CD8 T cells within EMD and reinforce the observation that these distinct populations may occupy separate sites within the lesion.

ST reveals microenvironmental differences between responders and nonresponders to bispecific antibody treatment

One of EMD's major unmet challenges is its significantly lower response rate to novel immunotherapies. Because we previously found the exclusion of functional CD8+ cytotoxic T cells from PC-enriched niches, we wanted to investigate whether this might contribute to the therapeutic response. We thus took advantage of our ST approach to investigate the mechanism of resistance in 3 patients with EMD (PT07, PT08, and PT10B) undergoing bispecific antibody treatment at the time of sampling (Figure 6A-C). PT07 responded well to talquetamab, a GPRC5D-targeting bispecific, but a single soft tissue mass of 3.7 × 1.9 cm originating from the sternum remained 18F-fluorodesoxyglucose (FDG)-avid on positron emission tomography–computed tomography scans after 14 months of treatment. Later, the patient experienced complete resolution of the soft tissue mass (Figure 6D). In contrast, PT08 had extensive EMD involvement of the skin and was primarily refractory to teclistamab, a BCMA-targeting bispecific. A biallelic hit in BCMA with subsequent antigen loss was excluded by WGS in this case (supplemental Figure 6J; supplemental Table 5). Finally, PT10 underwent talquetamab treatment and exhibited a heterogeneous response depending on the organ that harbored EMD. Comparing the ST data of all patients with EMD, the sample of PT07 had the lowest abundance of PCs (P < .001; Figure 6B-H; supplemental Figure 6A-C). In contrast, this sample showed features of a more intact immune function with the highest abundance of M1 macrophages (P < .001, Wilcox test) and a lower degree of exhausted T cells (T cells TIM3+) compared with the other patients (P < .001, Wilcox test; Figure 6D-F). In contrast, EMD samples of PT08 and PT10B showed a high abundance of exhausted T cells, and the few CD8+ cytotoxic T cells were again located in PC-free regions at the biopsy margins and did not infiltrate the lesion (Figure 6E-G; supplemental Figure 6A-C). Although the data are based on a limited number of cases, it may be postulated that there is a correlation between intralesional T-cell exhaustion and resistance to bispecific antibodies. This hypothesis requires further investigation and confirmation in future studies.

Discussion

Using state-of-the-art technology, we were able to dissect the spatial architecture of EMD and uncover a multicellular ecosystem within 3-dimensional tumor lesions. As expected, most cells were PCs, but we also found immune cells, especially T cells. They showed focal and diffuse infiltration patterns, a typical picture reminiscent of solid tumors.52

Our approach revealed genomic instability in PCs, with both shared and diverse CNVs among tumor cells. Subclonal CNVs suggest the emergence of new genetic variants that contribute to treatment resistance and poor outcomes in EMD. Although we assumed the Warburg effect to be active in EMD (lesions are typically positive on 18F-FDG–positron emission tomography), we identified oxidative phosphorylation as the major metabolic program in PC-rich areas. Interestingly, similar observations have been made in other hematologic malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia and lymphoma, which are resistant to chemotherapy or B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibition.53-55 Notably, in solid cancers, oxidative phosphorylation has been associated with decreased response rates to chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibition.56-59

We found an immune infiltrate in many EMD specimens, contrary to the previous perception of EMD lesions. Thus, according to the definition of Camus et al,60 Galon and Bruni,61 or Dhodapkar,62 EMD lesions could be considered as T-cell–infiltrated lesions because the majority appeared relatively rich in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Our transcriptomic approach uncovered spatial phenotypic differences between T cells and macrophages. Exhausted T cells were found to be colocalized with PCs, whereas activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and M1 macrophages were found in PC-free areas or at the biopsy margins. This suggests that T cells become dysfunctional and exhausted upon entering tumor lesions. The cause of these changes is unclear, possibly resulting from direct interactions between the plasma and immune cells or a distinct metabolic microenvironment lacking specific amino acids and nutrients, as hypothesized in other cancers.63,64 TIM3, the key T-cell exhaustion marker in our data, was noted for its role in T-cell exhaustion and suppression of innate immune responses in various malignancies.65-67 Although checkpoint inhibition failed in randomized trials in R/RMM,68 it could be evaluated in EMD once more, as T cells expressed programmed cell death protein 1.

The presence of EMD has been associated with decreased response rates and progression-free survival in recent chimeric antigen receptor T-cell and bispecific trials. Our study argues for dual- or multiepitope targeting because GPRC5D and TNFRSF17 expressions were heterogeneous in our EMD samples. Simultaneous targeting of both antigens could result in a higher number of bound antibodies per tumor cell. Indeed, the ongoing Phase 1b RedirecTT-1 study supports our hypothesis. The overall response rate in patients with EMD (n = 35) treated with teclistamab and talquetamab was 71.4%, nearly double the overall response rate of the respective monotherapies.68,69 We also began to understand the spatial coordination of immune response after successful bispecific antibody treatment. In this scenario, M1 macrophages and activated CD8 T cells can infiltrate the lesions and eradicate myeloma cells. However, this process may take several months, as observed for PT07.

Our study has several limitations. To our knowledge, we were the first to use the 10x Visium ST platform in MM, which poses challenges related to tissue preservation and composition. Likewise, our setup was not optimized for BM biopsies, which did not allow a paired analysis of EMD and concurrently assessed BM samples. Another drawback was the resolution, which was only close to the single-cell level. Overall, we worked with mostly small, routine clinical tissue samples from heavily pretreated patients that represented only a small fraction of the EMD mass and did not necessarily include the regions of interest. Samples from treatment-naïve patients would be of great interest but are only found in <5% of newly diagnosed patients with MM. The number of biopsies was limited, primarily from accessible skin or muscle lesions, restricting additional analyses, such as genomic profiling and functional T-cell experiments. As a result, we cannot answer the question of whether genomic features, such as a particular mutational profile, influence the immune microenvironment in EMD, as has previously been shown for intramedullary MM70 or non–small-cell lung cancer.70,71 However, our experimental setup provided a unique insight into the spatial organization of extramedullary PC tumors. The combination of microanatomical architecture and gene expression data surpasses the capabilities of traditional technologies and heralds an era of multiomics analysis that includes spatial information.

In conclusion, we identified T-cell exhaustion and profound genomic heterogeneity as novel hallmarks of EMD. We have uncovered a complex cell composition and provided a rationale for dual targeting with anti-BCMA and anti-GPRC5D agents in this difficult-to-treat condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study. The authors further acknowledge the sequencing efforts of the Core Unit SysMed, and especially Panagiota Arampatzi.

The authors thank the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Core Unit of the Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung (IZKF) Würzburg for the support of this study. M.J., M.H., G.M., N.A., K.M.K., A. Riedel, and L.R. were supported by the German Cancer Aid via the Mildred Scheel Early Career Centre (MSNZ) program (grants NG-2 and NG-4). S.-K.K. and L.R. thank the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung: Twinsight program for their support. L.R. is supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) (TissueNET, grant 031L0311B), and the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation. This study was funded by IZKF Project Z-12. T.J. was supported by the Czech Health Research Council (grant NU23-03-00374).

Authorship

Contribution: M.J., M.H., A. Riedel, and L.R. contributed to the study design; J.D., M.J.S., X.Z., J.M., J.M.W., C.R., S.-K.K., H.E., K.M.K., and L.R. provided study material from the patients; M.J.S. provided detailed clinical data on the patients; R.A.W. performed and analyzed the positron emission tomography scans; M.J. and E.S. performed immunostaining; M.J. and A. Riedel interpreted the immunostainings; J.D. performed ultrasound-guided biopsies; M.J. performed tomo sequencing; K.K. helped analyze tomo sequencing; M.J. and G.M. performed 10x Visium spatial transcriptomics; M.J. and M.H. performed single-cell RNA sequencing; M.H., A.M.L., N.A., D.Ž., A.A.S., and T.J. performed bioinformatics data analysis; M.T. and C.H. performed the whole-exome sequencing data analysis; A. Rosenwald analyzed the pathological samples; M.J., M.H. conceived the figures with input from A. Riedel and L.R.; M.J., M.H., A. Riedel and L.R. wrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.D. has received research support from Regeneron and Incyte, and has received honoraria from Incyte and MorphoSys. R.A.W. is speaker honoraria from Novartis/AAA and PentixaPharm; reports advisory board work for Novartis/AAA and Bayer; and is involved in [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET Imaging in PAN Cancer (FORPAN, sponsored by PentixaPharm). H.E. has participated in scientific advisory boards for Janssen, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda; has received research support from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, and Novartis; and has received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda. L.R. received honoraria from Janssen, BMS, Pfizer, Amgen, GSK and research support from SkylineDx. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Leo Rasche, Department of Internal Medicine 2, University Hospital Würzburg, Oberdürrbacher Str, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; email: rasche_l@ukw.de; and Angela Riedel, Mildred Scheel Early Career Center, University Hospital Würzburg, Versbacher Str 7, 97078 Würzburg, Germany; email: angela.riedel@uni-wuerzburg.de.

References

Author notes

M.J. and M.H. contributed equally to this study.

A. Riedel and L.R. are joint last authors.

Raw sequencing and processed files have been submitted to the European Genome-Phenome Archive (ID EGAS50000000227) and will be made available after publication.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![ST reveals microenvironmental differences between therapy-responsive and therapy-resistant patients. (A-C) Leiden clustering of spots based on the cell type abundances for PT07 (A), PT08 (B), and PT10B (C). (D) Maximum-intensity projection (MIP) and transaxial [18F] fluorodesoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography. The leftmost panels show PT07 at baseline and multiple lesions on both sides are indicated by arrowheads. In the middle panel, after talquetamab treatment, a follow-up scan was conducted 14 months later. A punch biopsy was taken from the lesion indicated by the circle. The rightmost panels display a follow-up scan after 20 months. Arrows indicate location of biopsied lesion. (E-G) Cell type abundances of PCs, macrophages M1, CD8+ T cytotoxic, and T-cells Tim3+ for PT07 (E), PT08 (F), and PT10B (G). (H) Cell type abundance comparing PCs, macrophages M1, and T-cells Tim3+ in all patients. Pairwise comparisons were implemented using the Wilcoxon test; ∗∗∗P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/20/10.1182_blood.2024024590/3/m_blood_bld-2024-024590-gr6.jpeg?Expires=1768639481&Signature=uRG-hAwQHaoi9noGlUoza~uwz3vj7k31G9D2XJCJzcC0JuQvo~bhZgkcaRqV1GeDy4SGpkrhQMP8WjPulQd6soxV0Cp6H5YJA1iH5WPMdKaWQNcNSzDz4~9RCMapQV4UNVXN0ihMKWl-FB~0txzqHePs8EQZ25gcszg7c1Vt6tXCYZd3woAPG9C-mDrjHZFWWo77cvesrquUzcbOBZzFKfJzNwlvsUc37bLTRFdkgh7~RFB3U0E-NmMv3HE2~Uz6jslZxcFJqlKmUbFnfEUBr59SF3RNOQfj~vkl8dkN5wJSi~-QwLR-LwW5XsvFcfjSRyZe3ADmCCFI9iN56e0icQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal