In this issue of Blood, Mateos-Jaimez et al1 establish LEF1 as a novel molecular player in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), with effects dependent upon protein levels and isoform composition due to switching.

LEF1 is a transcriptional target and canonical partner of β-catenin and acts as the main transcriptional mediator of the Wnt/B catenin pathway, where it regulates expression of genes involved in cell survival and proliferation.2 By using a large cohort of molecularly typed primary CLL cells, Mateos-Jaimez et al show increased LEF1 protein expression in samples with unmutated (UM-CLL) immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IgHV) genes compared to IgHV-mutated (M-CLL) ones. This is attributed to posttranscriptional stabilization events as LEF1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels are generally uniform throughout the cohort, including in monoclonal B lymphocytosis cells. Importantly, LEF1 protein levels are associated with a significantly shorter time to first treatment. Activation of primary CLL cells through B-cell receptor (BCR) triggering or by mimicking microenvironmental interactions upregulate LEF1 protein levels. This effect is driven, at least in part, by MYC, which is a direct transcriptional activator of LEF1, as CRISPR knockouts of MYC sharply reduce LEF1 protein. Moving to functional studies, the authors show differential genomic distribution of LEF1 in UM-CLL compared to M-CLL, with the former showing unique peaks localized in chromatin accessible sites, a characteristic that is maintained upon BCR activation. Transcribed genes in the UM-CLL category belong to cell cycle, cell proliferation, oxidative phosphorylation, and MYC targets, rather than survival genes, which represent the dominant signature in M-CLL cells.

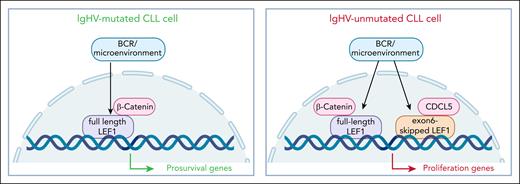

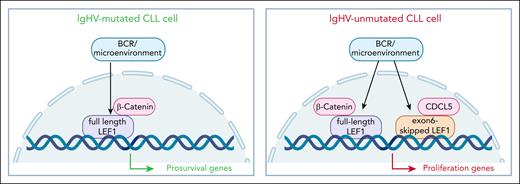

Finally, following evidence obtained in T lymphocytes,3 neurodevelopmental models,4 and solid cancers5 indicating that LEF1 exists in different isoforms, characterized by different transcriptional activities, the authors show that UM-CLL cells preferentially express a shorter version of LEF1, characterized by exon 6 skipping. This LEF1 isoform drives expression of proliferative genes, whereas the full-length form of LEF1, preferentially expressed by M-CLL, regulates an antiapoptotic gene signature. Accordingly, in both in vitro cultures and in vivo models, CLL cells with short LEF1 isoforms outgrow their full-length counterparts. This different behavior is attributed to the distinct transcriptional programs activated by LEF1 isoforms via differential cofactor recruitment. One such partner identified in this study is CDC5L, a cell cycle–regulating spliceosome factor that selectively interacts with short LEF1 isoform in UM-CLL, potentially linking LEF1 to mRNA processing and cell-cycle control (see figure).

LEF1 is a novel molecular player in CLL, with effects depending on protein levels and isoform switching. Specifically, IgHV-unmutated CLL cells are characterized by higher levels of LEF1 and by the presence of a shorter isoform. Together, these quantitative and qualitative changes induce differential binding to the DNA, triggering expression of proproliferation genes, at variance with IgHV-mutated CLL cells where the modulated pathways involve mostly prosurvival genes.

LEF1 is a novel molecular player in CLL, with effects depending on protein levels and isoform switching. Specifically, IgHV-unmutated CLL cells are characterized by higher levels of LEF1 and by the presence of a shorter isoform. Together, these quantitative and qualitative changes induce differential binding to the DNA, triggering expression of proproliferation genes, at variance with IgHV-mutated CLL cells where the modulated pathways involve mostly prosurvival genes.

Although LEF1 expression in CLL was previously reported as a diagnostic marker6,7 linked to the activation of prosurvival programs,8,9 this study extends our understanding of LEF1’s functions in CLL in 2 ways. First, it establishes LEF1 as an oncogenic driver in the disease, upregulated at the protein level in response to microenvironmental signals, including BCR ligation. This quantitative modulation, which is apparent in UM-CLL but not in M-CLL, may qualitatively affect its DNA binding activities, by inducing transcription of cell cycle regulation, metabolism, and mRNA processing genes, which are not constitutive LEF1 targets. Consistently, at least in the patient cohort used in the work, LEF1 expression levels carry independent prognostic significance. Second, it establishes LEF1 as a dynamic oncogene, which shifts from prosurvival to proproliferative factor through isoform switching. The concept that the same gene may code for proteins with differing, or even opposing functions, is well known in cancer, as underlined by the fact that alternative splicing has been proposed a hallmark of cancer.10 In the case of LEF1 in the context of CLL, the full-length isoform regulates expression of prosurvival molecules, whereas upon skipping of exon 6, it modulates proproliferative genetic programs. Because exon 6 contains the β-catenin–binding domain, this observation suggests that LEF1’s proproliferative activity in CLL may not strictly require canonical Wnt signaling and β-catenin binding. Consistent with this, LEF1-activated genes include E2F targets, MYC targets, and mTOR pathway genes, which are beyond the traditional Wnt target repertoire. This could explain why CLL cells, which often have minimal nuclear β-catenin, can still leverage LEF1 for proliferation.

This study leaves several open questions to future research. From the basic science standpoint, the signals that induce LEF1 protein accumulation need to be fully elucidated, including identification of intracellular molecular partners. A starting point could be to study the associations between expression of the different LEF1 isoforms and specific genetic lesions of the CLL cell, first and foremost those involving splicing mechanisms, such as SF3B1 mutations, a gene which intriguingly appears to be under LEF1 transcriptional control. Moving from correlations to function, the microenvironmental cues that the authors of the study refer to, will need to be teased out, not only in terms of determining whether they induce accumulation of LEF1 protein, but also in terms of understanding which LEF1 isoform they modulate. Additionally, critical and detailed information on the mechanisms that induce exon 6 skipping needs to be ascertained as this information has translational implications. It is important to recognize the effects derived from targeting the full-length vs the short version of LEF1 in the context of CLL. There is intense interest in targeting alternative splicing for cancer therapy by using different approaches, ranging from inhibiting key spliceosomal proteins or regulatory splicing factors to modulating specific alternative splicing events.10 Lastly, additional studies are needed to determine whether this regulatory mechanism is typical of CLL or whether it is shared by other hematological malignancies of the B series, starting with Richter transformation.

In conclusion, this study advances CLL research by revealing that LEF1 is not just a static marker or a prosurvival transcription factor but, rather, a dynamic regulator shaped by the microenvironment. These novel findings challenge us to rethink how alternative splicing contributes to cancer and highlight novel potential vulnerabilities that could be exploited therapeutically.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.