In this issue of Blood, Tapper et al1 present genome-wide association analyses to identify germ line genetic determinants of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) phenotypes and leverage this to refine genetic risk prediction.

MPNs are clonal blood cancers driven by the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and excessive production of mature myeloid cells. Most cases arise from somatic activating mutations of the JAK–STAT signaling pathway and carry risks of progression to myelofibrosis or leukemic transformation. Despite these shared features, MPNs display striking clinical and phenotypic diversity, with subtypes defined by their predominant lineage output. The classical Philadelphia chromosome-negative subtypes include polycythemia vera (PV), defined by excess red blood cell production, and essential thrombocythemia (ET), characterized by excess platelet production. What determines this lineage specificity? Driver mutations certainly play a role: although nearly all PV cases carry JAK2 V617F, 50% to 60% of ET cases harbor this mutation, with the remainder involving CALR, MPL, or no known driver (“triple negative”). Yet, as both PV and ET frequently originate from the same JAK2 V617F mutation arising within HSCs, a central unresolved question is how a single somatic lesion can give rise to diverse MPN subtypes.

Increasing evidence highlights germ line predisposition as a key modifier of MPN phenotypes. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have uncovered both common and rare germ line variants that influence MPN risk through modulation of HSC function.2-5 Intriguingly, although first-degree relatives of affected individuals carry a five- to seven-fold increased risk of any MPN, such kindreds reveal increased propensity to develop the same MPN subtype.6 Recent work reveals that each 1 standard deviation increase in polygenic risk score (PRS) of predicted platelet count confers a ∼1.5-fold higher odds of ET diagnosis.7 Together, these clues implicate inherited genetic variation in shaping MPN phenotypes, although a systematic evaluation has been lacking.

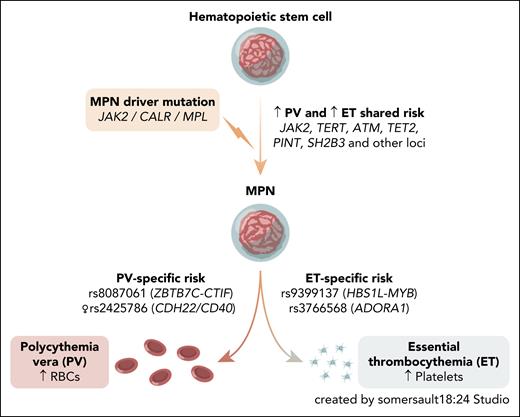

To this end, Tapper et al sought to identify germ line variants that influence MPN lineage specificity. Using a 2-stage case-only design, the authors first performed a GWAS comparing PV and ET among JAK2 V617F-positive cases, followed by replication in 4 independent European cohorts. Although many known MPN risk variants conferred susceptibility to both subtypes, this analysis highlighted a handful of variants with divergent effects between PV and ET (see figure). Notably, stratified analyses revealed a novel female-specific association at the CDH22/CD40 locus, where the risk allele increases susceptibility to PV but protects from ET. The authors propose that this PV-specific risk variant may interact with sex-specific biological processes, although mechanisms at this locus remain to be clarified.

MPN arises from somatic driver mutations in HSCs. Although most germ line risk loci predispose broadly to both PV and ET, Tapper et al identify common variants with opposing lineage-specific effects. RBC, red blood cell.

MPN arises from somatic driver mutations in HSCs. Although most germ line risk loci predispose broadly to both PV and ET, Tapper et al identify common variants with opposing lineage-specific effects. RBC, red blood cell.

The authors next used their subtype-specific genetic analyses to refine MPN risk prediction. They built a PRS from 48 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, adjusting for age, sex, and genetic ancestry. A subtype-agnostic PRS moderately predicted overall MPN risk (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.718). However, incorporating subtype-specific effects improved performance in UK Biobank, with PRSPV (AUC = 0.724) and PRSET (AUC = 0.755). These results highlight how accounting for subtype-specific genetic predisposition enhances predictive accuracy and helps dissect clinical heterogeneity of MPNs.

Despite these advances, several important questions remain. First, the study focused primarily on common variants, yet rare germ line alleles—such as those at CTR92 and CHEK23—can markedly increase MPN risk. Future efforts that integrate both common and rare variants in subtype-specific models will be highly informative. Second, the biological mechanisms by which germ line variants influence lineage specificity in MPN are unresolved. Such variants may bias a multipotent HSC with multilineage potential, or alternatively, act on already lineage-biased HSC subsets that exist at the apex of hematopoiesis.8 Third, the clinical utility of genetic risk prediction remains uncertain. Although these approaches could enable targeted prevention or screening, such end points raise concerns about overtreatment and inducing anxiety in a disease that has an indolent course for many. The greatest impact will likely come from integrating inherited risk with clinical parameters and profiling of clonal hematopoiesis9 to better define truly high-risk populations that may benefit from intervention.

Overall, the elegant study by Tapper et al advances our understanding of how genetic variation can affect subtype-specific risk profiles. In addition, their findings provide a foundation for functional studies exploring how germ line variation interacts with somatic drivers such as JAK2 V617F to shape clinical phenotypes. Increasingly accessible genome-editing tools now make it feasible to model these variants in relevant cellular systems,10 opening opportunities to understand mechanisms governing lineage specification in normal hematopoiesis and in MPNs. More broadly, this study highlights the power of germ line genetics to trace shared roots and divergent branches of MPN predisposition, a paradigm with broad scientific and clinical relevance across other cancers.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.