Abstract

The interleukin-3 (IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and IL-5 receptor α chains are each composed of three extracellular domains, a transmembrane domain and a short intracellular region. Domains 2 and 3 constitute the cytokine receptor module (CRM), typical of the cytokine receptor superfamily; however, the function of the N-terminal domain is not known. We have investigated the functions of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of the IL-3 receptor (IL-3R) α chain. We find that cells transfected with the receptor β chain (hβc) and a truncated IL-3Rα that is devoid of the intracellular region fail to proliferate or to activate STAT5 in response to human IL-3, despite binding the IL-3 with affinity indistiguishable from that of full-length receptor. In addition, IL-3–induced phosphorylation of hβc was not detected. Thus, the IL-3Rα intracellular region does not contribute detectably to stabilization of the receptor/ligand complex, but is essential for signal propagation. In contrast, a truncated IL-3Rα with the N-terminal domain deleted interacts functionally with the β chain; mouse cells transfected with these receptor chains proliferate in response to human IL-3 and STAT5 transcription factor is activated. High- and low-affinity binding sites are retained, although the affinity for IL-3 is decreased 15-fold, indicating a significant role for the N-terminal domain in IL-3 binding.

HEMATOPOIESIS AND LEUKOCYTE function are regulated by a large family of hematopoietic cytokines.1 These molecules are glycoproteins, typically 100 to 200 amino acids in length, folded in a four alpha helix bundle.2,3 They promote the generation of the various hematopoietic cell lineages from bone marrow precursors, and regulate the functions of the mature cells. Although rather dissimilar in primary amino acid sequence, they have a common tertiary structure and are encoded by genes with a similar number of exons and introns with a conserved organization (see Boulay and Paul4 for review). Members of this hematopoietic cytokine family include granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF ), erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and most of the interleukins, as well as growth hormone and prolactin.

The subunits of cytokine receptors also form a family, bearing similarities in both protein and gene structure.5 Members of the cytokine receptor superfamily are characterized by the presence of a 200-amino acid extracellular cytokine receptor module (CRM) composed of two discrete folding domains, each of which contains seven β strands folded into antiparallel sandwiches, and bears a structural similarity to the immunoglobulin constant domains.6,7 This predicted structure has been confirmed for two members of the family, the growth hormone receptor and prolactin receptor, by x-ray crystallography studies.8,9 Primary sequence conservation is limited to a number of individual residues within the CRM, including four conserved cysteine residues that are located in the N-terminal domain of the CRM, and a membrane proximal Trp-Ser-Xaa-Trp-Ser (where Xaa is any amino acid) motif, also known as the “WSXWS box,” located in the C-terminal domain.6,10,11 Some receptors contain additional extracellular domains. For example, the thrombopoietin receptor12 and the common chain of the interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5, and GM-CSF receptors (hβc)13 contain two CRMs, the G-CSF receptor contains three fibronectin type III domains between the CRM and the transmembrane domain, and the IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptor α chains all contain an additional domain N-terminal to the CRM.

The receptors for GM-CSF,14 IL-3,15 and IL-516 are each heterodimers made up of a ligand-specific α chain and hβc, with the three α chains being more closely related to each other in primary sequence than to other members of the superfamily.17 Given their interaction with a common chain, it is intriguing that the IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptor α chains share a similar domain structure. Furthermore, the N-terminal domains share significant sequence similarity (16% to 24% identity, 39% to 47% similarity17 ) suggesting that these N-terminal domains may play some role in receptor function. Each N-terminal domain has an odd number of cysteine residues, raising the possibility that disulfide formation, either with hβc, between two α chains, or between two domains of the α chain, may be involved in receptor activation.

The similarity between the members of the receptor family allows sequence alignment and structural modeling to be performed.17 From the known structure of the complex of growth hormone bound to its soluble receptor (growth hormone binding protein),8 it is evident that a ligand binding pocket is formed between the two domains of each CRM. This feature is included in our model of the IL-3/ILR complex, and is supported by mutagenesis studies on the IL-3 ligand,18,19 IL-3Rα (Barry et al, in preparation), and hβc.20 21 However, as the growth hormone receptor does not contain an additional N-terminal domain, modeling the IL-3R on the growth hormone receptor structure gives no indication of the role of this extra domain in the IL-3Rα. We therefore performed experiments to assess the role of this domain.

In this study, we have constructed IL-3 receptor α chains devoid of either the N-terminal domain or the C-terminal domain to probe the role of these domains in receptor function. We find that removal of the N-terminal domain reduces, but does not abolish, binding of IL-3. When this truncation was compared with a full-length receptor for its ability to form a high-affinity complex and to induce a proliferative signal, we observed a reduction in proliferative potency that was similar to the reduction in observed binding affinity. However, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (MoAb) that can compete with IL-3 for binding to IL-3Rα chain in a dose-dependent manner was unable to bind to the truncated receptor. Furthermore, this antibody was unable to neutralize the IL-3–dependent proliferation of cells coexpressing the truncated receptor and a normal hβc. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain of IL-3Rα resulted in wild-type high-affinity ligand binding, when compared with the full-length IL-3Rα coexpressed with hβc, demonstrating that the cytoplasmic domain is not required for receptor complex formation. Nevertheless, when this truncated receptor was coexpressed with hβc in FDC-P1 cells, these cells were unable to proliferate in response to hIL-3.

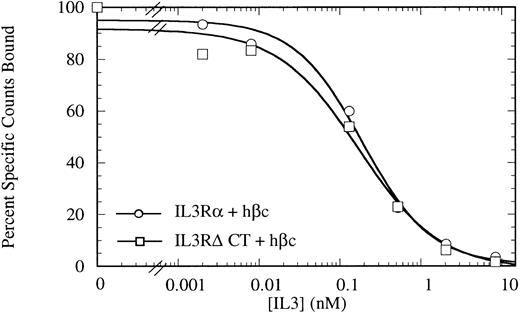

Competitive binding assay showing indistinguishable high-affinity binding kinetics for COS cells transiently expressing IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔCT + hβc (□). Cells were treated with 150 pmol/L 125I-IL–3 and a titration of cold competitor was performed. Data are the mean of triplicate points.

Competitive binding assay showing indistinguishable high-affinity binding kinetics for COS cells transiently expressing IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔCT + hβc (□). Cells were treated with 150 pmol/L 125I-IL–3 and a titration of cold competitor was performed. Data are the mean of triplicate points.

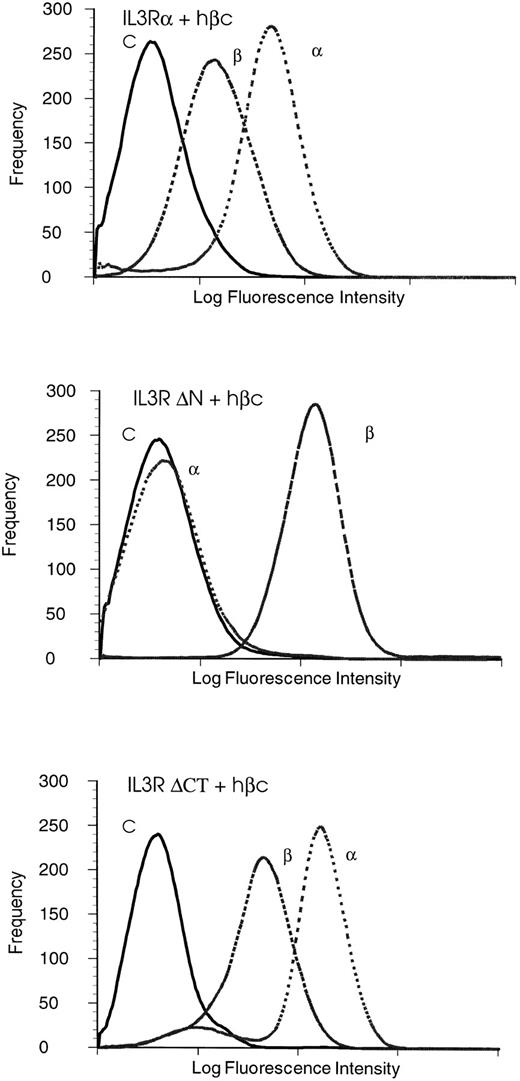

Analysis of surface expression on FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc or IL-3RΔNT + hβc or IL-3RΔCT + hβc by flow cytometry using isotype control MoAb (C), MoAb 1C1 for hβc detection (β), and MoAb 7G3 for IL-3Rα detection (α). IL-3Rα and IL-3RαΔCT are expressed at similar levels, but IL-3RαΔNT is not recognized by the MoAb 7G3.

Analysis of surface expression on FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc or IL-3RΔNT + hβc or IL-3RΔCT + hβc by flow cytometry using isotype control MoAb (C), MoAb 1C1 for hβc detection (β), and MoAb 7G3 for IL-3Rα detection (α). IL-3Rα and IL-3RαΔCT are expressed at similar levels, but IL-3RαΔNT is not recognized by the MoAb 7G3.

To analyze the early FDC-P1 signaling pathways activated in response to the IL-3, we followed the phosphorylation of hβc and activation of STAT proteins22-25 by JAK kinases, which have recently been found to associate with hβc.26 27 To do this, we performed both immunoprecipitation assays (for analyzing phosphorylation of hβc) and gel retardation assays using a STAT recognition sequence from the β-casein promoter. These experiments show that both the wild-type and N-terminally truncated, but not the C-terminally truncated, receptor α chain mediate phosphorylation of hβc and activation of STAT5. These results indicate an involvement of the N-terminal domain of the IL-3Rα in ligand binding, with the implication that the homologous domain in the GM-CSF and IL-5 receptors may also play a role in ligand binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis of the IL-3Rα sequence.The IL-3Rα cDNA was subcloned into pALTER (Promega Inc, Madison, WI) site-directed mutagenesis vector, and single-stranded DNA was prepared and used as the template for oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis, as detailed in the manufacturer's protocol. A 237-bp deletion (aa 2-80 of the mature protein), corresponding to the entire 80 amino acid predicted N-terminal domain (oligo: 5′ GCT TCC CAC TGT TCT CCT TCG TTT GCA GGA GA 3′), and the insertion of a stop codon in frame substituting aa314 to a termination codon (oligo: 5′ AAG AGT CTC TGC TAC ACC AGA TAC CT 3′) were performed to generate IL-3RΔNT and IL-3RΔCT, respectively. These mutants were sequenced to verify incorporation of the desired modification.

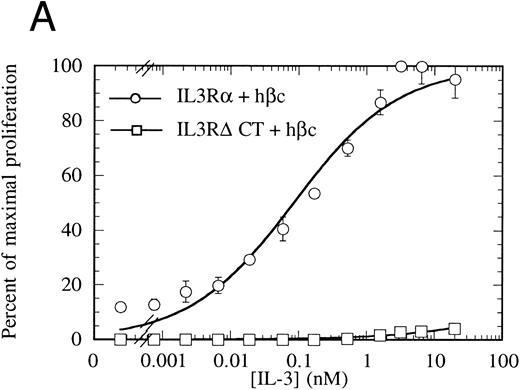

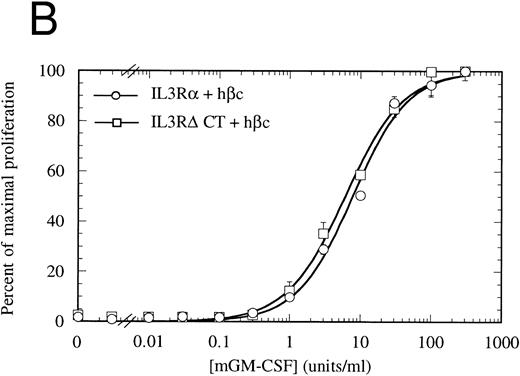

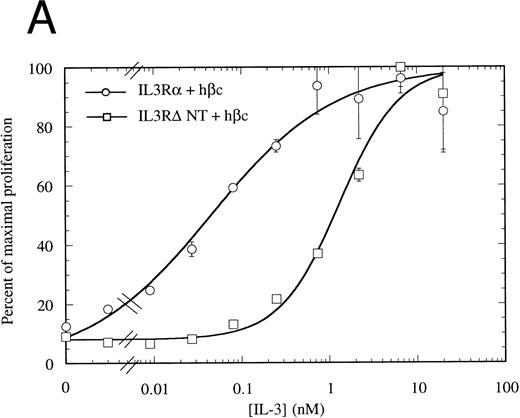

Proliferation of FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔCT + hβc (□) in response to hIL-3 (A) or, as a control for viability, mGM-CSF (B). Proliferation was determined using the CellTiter 96 nonradioactive assay (Promega). Data are the means of triplicate points ± standard deviation (SD).

Proliferation of FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔCT + hβc (□) in response to hIL-3 (A) or, as a control for viability, mGM-CSF (B). Proliferation was determined using the CellTiter 96 nonradioactive assay (Promega). Data are the means of triplicate points ± standard deviation (SD).

Retroviral expression.Wild-type or truncated IL-3Rα cDNAs were inserted into the Hpa I site of the retroviral vector pRufNeo.28 The hβc cDNA was subcloned into the Hpa I site of pRUFPuro. Constructs were transfected by CaPO4 precipitation into the amphotrophic retroviral producer line ψ2, as previously described.28,29 The murine, mGM-CSF–responsive, myeloid cell line FDC-P1 was used to assess the proliferative response from the wild-type or truncated IL-3 receptors. These cells were infected with retrovirus by cocultivation with the ψ2 producer cell lines, as detailed elsewhere.28

Cell culture and proliferation assay.For transient expression studies, the permissive COS cell line was used. These cells were maintained in culture in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 0.12 μg/mL penicillin, and 1.6 μg/mL gentamycin. For functional experiments FDC-P1 cells and ψ2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented as above. Selection for neomycin resistance was performed with G418 at 1 mg/mL for FDC-P1 cells, and 400 μg/mL for ψ2 cells. Cells infected with constructs expressing a puromycin resistance gene were selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO). Proliferation of retrovirally infected sublines of FDC-P1 in response to either hIL-3 or mGM-CSF was assayed using the CellTiter 96 nonradioactive cell proliferation assay kit (Promega Inc) based on the method originally described by Mosmann.30

Expression of the IL-3Rα and β chains on transfected cells.Full-length cDNA clones of IL-3Rα or mutated IL-3Rα chain were subcloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA1Neo (Stratagene Inc, La Jolla, CA) and transfected into COS cells by electroporation.31 Briefly, 108 cells were washed and resuspended in transfection buffer with DNA (10 μg IL-3Rα + 20 μg hβc), incubated for 10 minutes on ice, then electroporated in a 0.4-cm cuvette at 250 μF, 250 V on a gene pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Cells were plated into 175-cm2 flasks and incubated in standard tissue culture conditions (5% CO2 , 37°C). Two days after transfection, the cells were harvested with 5 mmol/L EDTA and used in binding assays. Expression of the receptor protein was assessed using fluorescent conjugate antibody staining techniques with MoAbs against both the IL-3Rα chain (9F5, 7G3) and hβc (4F3, 1C1), as detailed elsewhere.32 33

Radioreceptor assays.IL-3 was radio-iodinated by the iodine monochloride method34 and used in either direct competitive binding experiments as described35,36 or in equilibrium binding experiments37 using different concentrations of 125I-IL-3. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of at least 100-fold excess of unlabeled IL-3. EBDA-LIGAND software38 39 was used to determine dissociation constants (kd) and maximal binding (Bmax ). Binding experiments were performed with triplicate samples per data point, and results are representative of at least two separate experiments.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.Nuclear extracts were prepared from cytokine-treated FDC-P1 cells. Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were treated with varying concentrations of cytokine for 15 minutes and then nuclear extracts prepared as described previously.22 Protein quantitation was performed on nuclear extracts using the BCA reagent (Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed using a double-stranded oligonucleotide sequence corresponding to the canonical STAT5 binding site found in the β-casein promoter. The probe was labeled by end-filling 2 pmol of double-stranded oligonucleotide with overhanging 5′ ends using Klenow, 0.1 mmol/L dGTP/dCTP/dTTP, and 50 μCi [α32P]dATP. Binding reactions were performed in a total volume of 15 μL with 5 μL of nuclear exctract and 30 fmol of [32P]-labeled probe in the following buffer: 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 5 mmol/L MgCl2 , 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 7% glycerol, and 1 μg poly dI-dC. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 2 μg of nuclear extract protein and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes before electrophoretic analysis on a nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE buffer. In supershift experiments, the nuclear extracts were preincubated with chicken anti-STAT5 antibody40 or anti-STAT1 antibody from UBI (Lake Placid, NY) for 30 minutes before addition of the probe. Specificity was confirmed by addition of excess cold oligonucleotide or cold mutant oligonucleotide, which was unable to bind STAT proteins. The oligonucleotide probes used for competition studies were: (1) wild-type β-casein promoter probe (5′-AGATTTCTAGGAATTCAAATCC-3′); (2) mutant β-casein promoter probe (5′-AGATTTATATTAATTCAAATCC-3′). Results were analyzed by autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation.Murine FDC-P1 cells stably expressing the hβc and either of IL-3Rα, IL-3RαΔNT, or IL-3RαΔCT were washed three times and then cultured in the absence of human growth factor for 18 hours. For immunoprecipitation (IP), 2 × 107 cells were then lysed in 1 mL IP lysis buffer (as detailed elsewhere41 ), and precleared for 1 hour with Protein A Sepharose beads (AMRAD Pharmacia Biotech, Boronia, Vic. Australia). The cleared lysate was then incubated for 4 hours at 4°C with 100 μL of anti-hβc MoAb 4F3 coupled to Protein A Sepharose. The beads were washed four times with lysis buffer and the bound protein analyzed by reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on an 8% gel. Detection of phosphorylated protein was performed by Western blotting with a commercial antiphosphotyrosine MoAb 3-365-10, as detailed in the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer-Mannheim, Frankfurt, FRG).

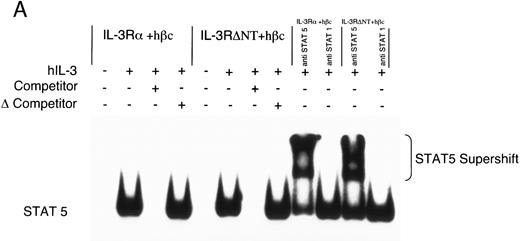

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using a STAT binding probe to demonstrate activation of STAT5 in FDC-P1 cells in response to hIL-3. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc or IL-3RΔNT + hβc and stimulated with or without 1 nmol/L IL-3. Specificity of binding was confirmed by addition of 100-fold excess cold competitor oligonucleotide, or 100-fold excess of a mutant oligonucleotide, which cannot bind STAT protein. The binding protein was verified to be STAT5 and not STAT1 by addition of specific antibodies to each: only anti-STAT5 antibody gave a supershift. (B) Analysis of dose responses to IL-3 by IL-3Rα + hβc, IL-3RΔNT + hβc, IL-3RΔCT + hβc, hβc only, untransfected FDC-P1 cells (FD-), and untransfected FDC-P1 cells stimulated with mGM-CSF as a positive control (last lane).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using a STAT binding probe to demonstrate activation of STAT5 in FDC-P1 cells in response to hIL-3. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc or IL-3RΔNT + hβc and stimulated with or without 1 nmol/L IL-3. Specificity of binding was confirmed by addition of 100-fold excess cold competitor oligonucleotide, or 100-fold excess of a mutant oligonucleotide, which cannot bind STAT protein. The binding protein was verified to be STAT5 and not STAT1 by addition of specific antibodies to each: only anti-STAT5 antibody gave a supershift. (B) Analysis of dose responses to IL-3 by IL-3Rα + hβc, IL-3RΔNT + hβc, IL-3RΔCT + hβc, hβc only, untransfected FDC-P1 cells (FD-), and untransfected FDC-P1 cells stimulated with mGM-CSF as a positive control (last lane).

RESULTS

The cytoplasmic domain is not necessary for IL-3 binding.To investigate the role of the IL-3Rα intracellular region, we generated a mutant IL-3Rα cDNA with a stop codon engineered at codon 314, just beyond the transmembrane region (deleting amino acids 314-360), which we call (IL-3RαΔCT). This cDNA was introduced into COS cells in conjunction with a human IL-3Rβ chain (hβc), and these cells were used for competitive binding assays. These cells bound IL-3 with high affinity indistinguishable from those of full-length receptors (Fig 1) with an ED50 for competition of radiolabel by cold IL-3 of 173 pmol/L versus 192 pmol/L for the wild-type receptor. This result indicates that any interaction between the intracellular region of IL-3Rα and hβc does not play a role in stabilization of the high-affinity receptor complex.

The cytoplasmic domain is essential for intracellular signaling.To assess whether the IL-3Rα intracellular region participates in intracellular signaling, we introduced a retroviral construct containing IL-3RαΔCT into hematopoietic cells. For these experiments, we used FDC-P1 cells, which require murine IL-3 or GM-CSF for survival and proliferation, but can proliferate in response to human IL-3 if transfected with functional human IL-3 receptor.42 The IL-3RαΔCT and as a control the wild-type IL-3Rα were each stably introduced into FDC-P1 cells that had been previously transfected with hβc. We used flow cytometry to verify that the receptors were expressed at similar levels in each of the cell lines (Fig 2). These cells were treated with human IL-3 and the cellular proliferation rate measured. We found that the proliferation of the cells transfected with IL-3RαΔCT was not stimulated by hIL-3 over the concentration range tested (Fig 3A). Cell viability was indistinguishable from the control cells expressing both IL-3Rα and hβc, as tested by proliferation in response to mGM-CSF (Fig 3B).

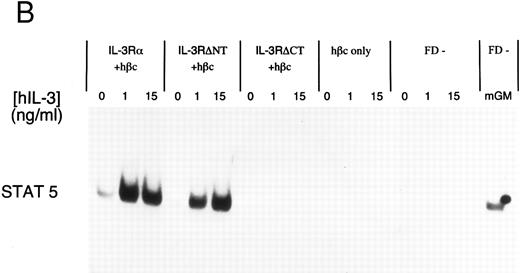

Antiphosphotyrosine Western blot of anti-hβc immunoprecipitate from FDC-P1 cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc, IL-3RΔNT + hβc, or IL-3RΔCT + hβc, with (+) and without (-) stimulation by 15 nmol/L hIL-3. Cells were cultured for 18 hours in the presence or absence of hIL-3 and the hβc immunoprecipitated with MoAb 4F3. Phosphoprotein in the immunoprecipitate was detected by Western blotting using antiphosphotyrosine MoAb 3-365-10 (Boehringer Mannheim).

Antiphosphotyrosine Western blot of anti-hβc immunoprecipitate from FDC-P1 cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc, IL-3RΔNT + hβc, or IL-3RΔCT + hβc, with (+) and without (-) stimulation by 15 nmol/L hIL-3. Cells were cultured for 18 hours in the presence or absence of hIL-3 and the hβc immunoprecipitated with MoAb 4F3. Phosphoprotein in the immunoprecipitate was detected by Western blotting using antiphosphotyrosine MoAb 3-365-10 (Boehringer Mannheim).

To further investigate the effects of cytoplasmic truncation of IL-3Rα on intracellular signaling, we performed gel retardation assays with an oligonucleotide probe containing a STAT recognition sequence, capable of binding STAT1 and STAT5. We first confirmed STAT5 protein was binding specifically to the probe using nuclear extracts from unstimulated and IL-3–stimulated cells expressing IL-3 receptors. This was analyzed by competition with either excess unlabeled oligonucleotide or excess unlabeled mutant oligonucleotide (which is unable to bind any STAT proteins) and by antibody supershift (Fig 4A). Addition of anti-STAT5 antibody, but not anti-STAT1 antibody, resulted in formation of a slower migrating complex in the gel shift assay. The IL-3–induced STAT5 activation was confirmed to be dependent on the expression of α chains by analysis of control extracts from either uninfected FDC-P1 cells or FDC-P1 cells expressing hβc only (Fig 4B). Neither of these cells was able to activate the STAT5 protein in response to hIL-3. Nuclear extracts from cells expressing the IL-3RαΔCT + hβc did not detectably activate STAT5 when stimulated with IL-3 (Fig 4B). Thus the intracellular region of IL-3Rα appears to be essential for generating proliferative signals in response to IL-3, and activation of STAT5 protein is also dependent on the cytoplasmic domain.

To determine the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain of the IL-3Rα to earlier activation events, we next performed an immunoprecipitation with a MoAb against hβc, and examined the phosphorylation of the hβc in response to IL-3. We found that when the C-terminal domain of IL-3Rα was deleted, IL-3 stimulation was no longer able to induce phosphorylation of hβc, when compared with IL-3Rα (Fig 5). To confirm that the lack of hβc phosphorylation was not simply due to a failure to immunoprecipitate the β chain from the IL-3RαΔCT cells, we quantitated the phosphotyrosine by phosphorimaging and also measured the hβc in the Western blot with anti-hβc antibody 1C1 (Table 1). These results suggest that the early activation events of the receptor complex require the interaction of the cytoplasmic domain of both receptor chains, or that the kinase required for phosphorylation of hβc interacts directly with the cytoplasmic domain of the α chain.

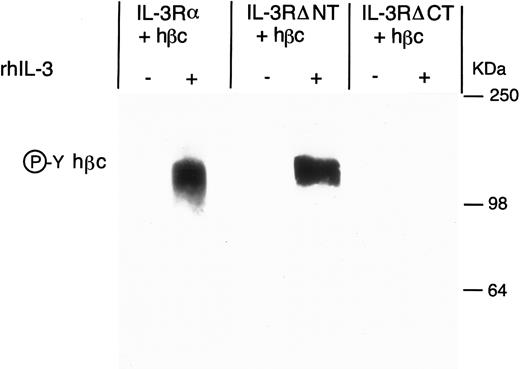

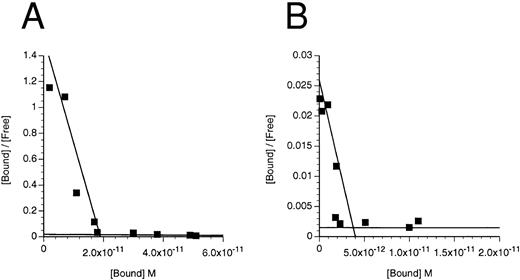

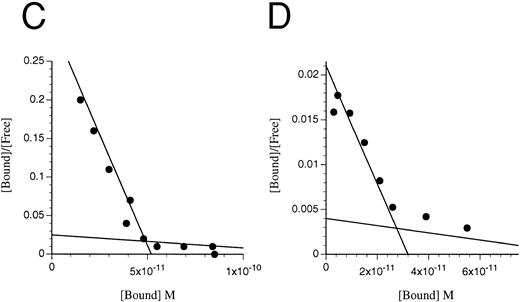

Deletion of the N-terminal domain reduces, but does not eliminate, IL-3 binding.To assess the role of the N-terminal domain, we used site directed mutagenesis to construct a cDNA encoding IL-3Rα devoid of the N-terminal domain (which we call IL-3RαΔNT). In initial experiments, we transfected COS cells with the IL-3RαΔNT cDNA, but were unable to reliably determine the kd of the specific binding of IL-3 (data not shown), indicating that either the IL-3RαΔNT was not expressed on the cell surface or the affinity of IL-3RαΔNT is significantly less than that of IL-3Rα (which has a kd of 50 to 100 nmol/L in the absence of hβc15). Because coexpression of hβc with IL-3Rα results in a higher affinity receptor,42 we cotransfected the IL-3RαΔNT cDNA with hβc cDNA into COS cells and measured the affinity of the expressed receptor 3 days later. Two classes of binding site were detected (Fig 6 and Table 2), indicating that the IL-3RαΔNT can be expressed on the cell surface and is able to interact with hβc to form a higher affinity complex. The higher affinity site bound IL-3 with approximately 15-fold reduced affinity compared with the higher affinity site on cells transfected with the IL-3Rα and hβc (kd = 1,231 ± 243 pmol/L v 82 ± 37 pmol/L, respectively). Importantly, a second, lower affinity site appeared to be present, with a kd of 1.6 ± 1.5 μmol/L (n = 2) compared with the IL-3Rα (kd = 28 ± 16 nmol/L; n = 5). We also performed binding experiments on the FDC-P1 cells expressing IL-3RαΔNT + hβc and found similarly decreased affinity and two-site binding kinetics (Fig 6, Table 2). These experiments demonstrate that the N-terminally truncated receptor binds IL-3 less avidly than the IL-3Rα, but can still interact with hβc, since two-site binding kinetics are observed.

Scatchard transformation of representative binding data. (A) COS cells transfected with IL-3Rα + hβc showing two site binding kinetics with a mean high-affinity kd of 80 pmol/L (n = 6, P < .001). (B) COS cells transfected with IL-3RΔNT + hβc also showing two site binding kinetics, but with a 14-fold decreased mean high-affinity kd of 1,146 pmol/L (n = 4, P < .001). (C) FDC-P1 cells stably expressing IL-3RαΔCT + hβc (high-affinity kd of 224 pmol/L). (D) FDC-P1 cells stably expressing IL-3RαΔNT + hβc (high-affinity kd of 1,600 pmol/L). Data points are the means of duplicates.

Scatchard transformation of representative binding data. (A) COS cells transfected with IL-3Rα + hβc showing two site binding kinetics with a mean high-affinity kd of 80 pmol/L (n = 6, P < .001). (B) COS cells transfected with IL-3RΔNT + hβc also showing two site binding kinetics, but with a 14-fold decreased mean high-affinity kd of 1,146 pmol/L (n = 4, P < .001). (C) FDC-P1 cells stably expressing IL-3RαΔCT + hβc (high-affinity kd of 224 pmol/L). (D) FDC-P1 cells stably expressing IL-3RαΔNT + hβc (high-affinity kd of 1,600 pmol/L). Data points are the means of duplicates.

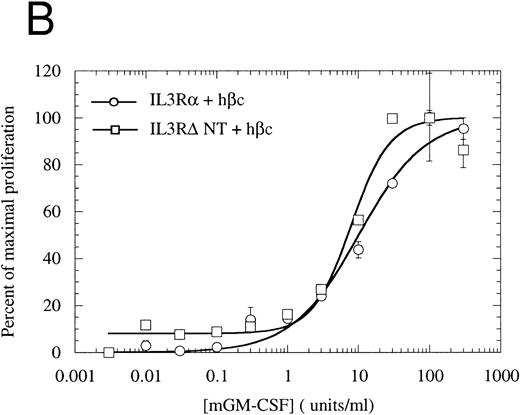

The N-terminally truncated IL-3Rα can form a functional receptor.To verify that IL-3RαΔNT retains the ability to interact with hβc, we investigated whether it retained the capacity to transmit intracellular signals in conjunction with hβc. FDC-P1 cells coexpressing IL-3RαΔNT and hβc proliferated in response to human IL-3, but with a reduced ED50 compared with that of cells expressing both IL-3Rα and hβc (Fig 7A). The 14-fold reduction in ED50 (8.03 ng/mL [518 pmol/L], n = 3, v 0.58 ng/mL [37.4 pmol/L], n = 3 for wild-type receptor, Fig 7A) closely paralleled the decrease in affinity observed in binding experiments (Fig 6, Table 2). In all cases, the cell pools were tested for their growth characteristics in mGM-CSF to ensure that the observed differences were not due to intrinsically slower growth. All pools were found to have similar dose response curves to mGM-CSF (Fig 7B). Scatchard analysis demonstrated that there was, at most, only a twofold difference in the number of high-affinity binding sites between the cells bearing IL-3Rα versus IL-3RαΔNT. Thus, interactions with hβc appear to be unaffected by removal of the N-terminal domain, further suggesting that interaction between the IL-3Rα N-terminal domain and hβc is not essential for receptor function. To confirm that the full-length and truncated receptors were signaling via the same cellular pathway, we performed gel retardation assays to assess STAT5 activation. Figure 4B shows that when coexpressed with hβc, both IL-3Rα and IL-3RαΔNT are able to mediate activation of STAT5 protein in response to stimulation with hIL-3. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation experiments showed that the IL-3–induced phosphorylation of hβc was indistinguishable for the IL-3RΔNT + hβc or IL-3Rα + hβc cell populations (Fig 5). We conclude that this IL-3–dependent signaling is via the same pathway for both receptors.

Proliferation assay in response to hIL-3 (A) or mGM-CSF, as a control for cell growth and viability (B) by FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (□). Cells expressing IL-3RΔNT + hβc show a mean 14-fold decrease in responsiveness to hIL-3 (ED50 = 518 pmol/L) compared with IL-3Rα + hβc (ED50 = 37.4 pmol/L, n = 3, P < .014). Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

Proliferation assay in response to hIL-3 (A) or mGM-CSF, as a control for cell growth and viability (B) by FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (□). Cells expressing IL-3RΔNT + hβc show a mean 14-fold decrease in responsiveness to hIL-3 (ED50 = 518 pmol/L) compared with IL-3Rα + hβc (ED50 = 37.4 pmol/L, n = 3, P < .014). Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

MoAb 7G3, which binds to the N-terminal domain of IL-3Rα, blocks binding of IL-3 to IL-3Rα, but does not inhibit binding of IL-3 to IL-3RαΔNT.The MoAb 7G3, raised against the wild-type IL-3Rα, has recently been shown to compete with IL-3 for binding to the receptor.33 In addition, IL-3 is able to inhibit 7G3 binding to the receptor. These results suggest that all or part of the epitope for MoAb 7G3 overlaps the IL-3 binding region of the receptor. We tested the ability of MoAb 7G3 to recognize full-length or truncated receptor expressed on both COS cells and FDC-P1 cells. When we used 7G3 in initial experiments to check for expression of IL-3RαΔNT on transfected cells, we were unable to detect binding of the MoAb by flow cytometry (Fig 2) or by Western blotting (data not shown), despite the clear detection of the full-length IL-3Rα by both techniques. This suggested that the N-terminal domain is required for binding of 7G3. That the IL-3RαΔNT subunit is expressed on the surface of the transfected FDC-P1 cell line was verified by Scatchard analysis on both COS cells (Fig 6B) and FDC-P1 cells (Fig 6D).

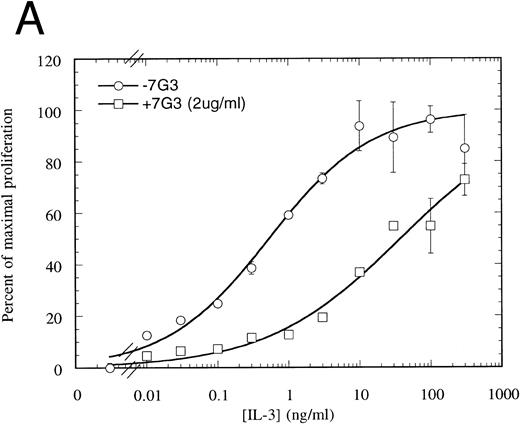

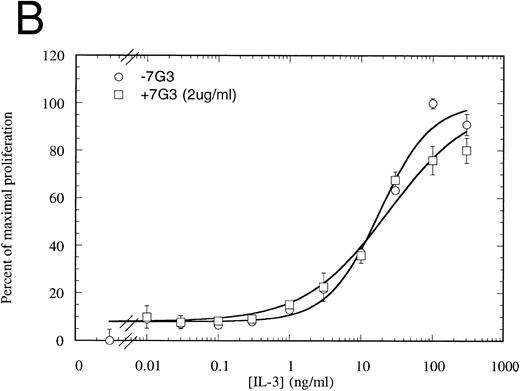

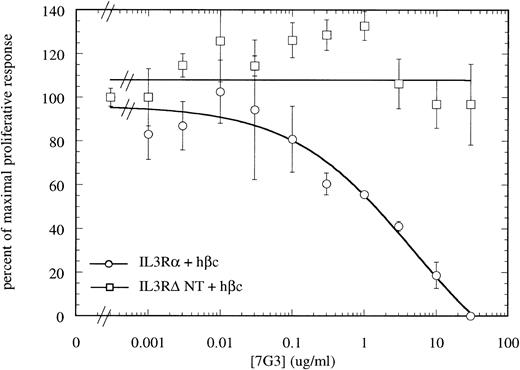

MoAb 7G3 is able to neutralize the biological response of a number of hIL-3–responsive cells, including TF-1 erythroleukemia cells, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECS).33 We tested the ability of MoAb 7G3 to neutralize the proliferation of FDC-P1 cells expressing the two forms of IL-3 receptor (IL-3RαΔNT + hβc or IL-3Rα + hβc). We first tested the effect of a fixed dose of MoAb 7G3 (2 μg/mL) on the dose response to IL-3 (Fig 8) and, as a control, mGM-CSF (data not shown). This MoAb showed no effects on mGM-CSF–mediated proliferation, but was able to significantly inhibit the stimulation by IL-3 of FDC-P1 cells expressing the IL-3Rα + hβc (Fig 8A). In contrast, MoAb 7G3 showed no effect on the IL-3–induced proliferation of FDC-P1 cells expressing IL-3RαΔNT + hβc (Fig 8B). To confirm this, various concentrations of MoAb were tested at a fixed concentration of IL-3 (5 ng/mL; 322 pmol/L), a concentration that gives maximal proliferation of both cell lines. Complete inhibition of growth of cells expressing IL-3Rα was seen at 30 μg/mL MoAb, with an ED50 of 2 μg/mL, whereas the proliferation of cells expressing IL-3RαΔNT + hβc was not significantly affected at any concentration of MoAb tested (Fig 9). This loss of MoAb binding on removal of the N-terminal domain suggests that all or at least part of the epitope for this MoAb lies in the N-terminal domain of the receptor. Since the binding epitope for 7G3 overlaps the IL-3 binding site, this indicates that the IL-3Rα N- terminal domain forms part of, or lies close to, the IL-3 binding site.

Proliferation assay in response to hIL-3 on FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (A) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (B) with (□) and without (○) a fixed concentration of MoAb 7G3, showing that this MoAb is able to neutralize IL-3–dependent proliferation from the wild-type receptor (A), but has no effect on IL-3–dependent proliferation from the truncated receptor at the concentration tested (B). Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

Proliferation assay in response to hIL-3 on FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (A) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (B) with (□) and without (○) a fixed concentration of MoAb 7G3, showing that this MoAb is able to neutralize IL-3–dependent proliferation from the wild-type receptor (A), but has no effect on IL-3–dependent proliferation from the truncated receptor at the concentration tested (B). Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

Titration of the neutralizing MoAb 7G3 against a fixed dose of hIL-3 (322 pmol/L) on FDC-P1 expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (□), showing complete neutralization of proliferation induced by hIL-3 on cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc, but no inhibition of IL-3–induced proliferation of cells expressing IL-3RΔNT + hβc. This confirms that the MoAb 7G3 cannot bind to the truncated receptor. Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

Titration of the neutralizing MoAb 7G3 against a fixed dose of hIL-3 (322 pmol/L) on FDC-P1 expressing either IL-3Rα + hβc (○) or IL-3RΔNT + hβc (□), showing complete neutralization of proliferation induced by hIL-3 on cells expressing IL-3Rα + hβc, but no inhibition of IL-3–induced proliferation of cells expressing IL-3RΔNT + hβc. This confirms that the MoAb 7G3 cannot bind to the truncated receptor. Data are the mean of triplicate points ± SD.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated the roles of the N- and C-terminal domains of the IL-3Rα. Because the IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF α chains all contain similar domains, and use a common signaling molecule (hβc), common functions could be postulated for the homologous domains. In the experiments presented here, we have observed that a truncation, which removes the entire cytoplasmic domain of the IL-3Rα, was completely unable to deliver a proliferative signal. This receptor was expressed on the cell surface at normal levels, and was able to bind IL-3 with high affinity when expressed along with hβc. These observations show that the interaction between the two receptor subunits, which results in heterodimerization, must reside in the extracellular domains of the proteins, but interactions between the cytoplasmic domains are essential for signaling. This has also been observed for both the IL5R43,44 and GM-CSFR.45

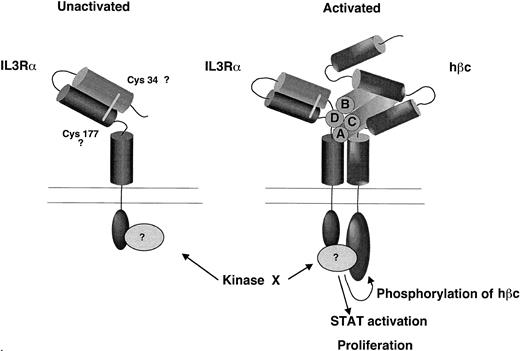

We find no STAT protein activation in response to hIL-3, suggesting that the pathway resulting in STAT activation is dependent on the cytoplasmic domain of the IL-3Rα. This domain appears to contain no intrinsic kinase activity, and so a molecule must be recruited to perform this activity. The initial step in activation appears to be phosphorylation of hβc.45 It has been recently demonstrated that STAT activation requires the interaction of JAK2 with hβc,27 and that JAK2 phosphorylates STAT5,22,23 but no role for the IL-3Rα in STAT activation has previously been determined. Our observations suggest there may be interactions between a kinase and the IL-3Rα, which leads to phosphorylation of hβc, and this allows additional interactions resulting in activation of STAT5. The identity of this molecule, and whether it also interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of hβc, have yet to be determined. It is suggestive that the cytoplasmic domains of both α and hβc chains contain a proline rich region (called box 1 in hβc) near the transmembrane domain. This proline rich box in hβc is required for JAK2 activation,27 46 and ultimately for proliferation. Perhaps the initial kinase activation that triggers the signaling pathway requires an interaction involving the proline rich boxes of both the α and β chains. Chimeric receptors in which the intracellular region of IL-3Rα is replaced by the intracellular domain of hβc47-49 may function because box 1 of hβc is functionally equivalent to the proline rich region of IL-3Rα.

We have also demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of the IL-3Rα contributes to the IL-3 binding site, but is not essential for ligand binding, since its removal results in a 14-fold reduction in high-affinity binding for IL-3, and also a reduction in low-affinity binding. The clear presence of two sites in the Scatchard analysis of binding experiments when IL-3RαΔNT and hβc were coexpressed strongly supports the interpretation that the defect is indeed in ligand binding and not a gross structural perturbation or a defect in interaction with hβc. In fact, the difference between high- and low-affinity kds appears to be greater for the N-terminally deleted receptor than for the full-length receptor, suggesting that the hβc is able to partially compensate for the binding defect caused by the N-terminal truncation. The role of hβc as an affinity converting molecule for all three α chains of the subfamily has been clearly demonstrated, and although the low-affinity binding of each receptor ranges from 50 nmol/L (IL-3Rα) to 500 pmol/L (IL-5Rα), all have a similar kd for high-affinity binding of approximately 100 pmol/L.

The 15-fold reduction in high-affinity binding to IL-3RΔNT + hβc is also reflected in a similar (14-fold) reduction in responsiveness to hIL-3 when the truncated receptor is coexpressed with hβc on murine FDC-P1 cells. Clearly, the truncated receptor can still interact with the hβc, since the receptor complex can signal in response to IL-3. We show that IL-3 responsiveness directly correlates with coexpression of hβc, and that IL-3–induced phosphorylation of hβc also occurs, implying that the wild-type and truncated receptors signal via the same pathway. The gel retardation assays confirm this observation, as the same STAT protein is specifically activated by these receptor complexes in response to stimulation with IL-3.

To test the functional significance of the N-terminal domain, we exploited the neutralizing properties of an MoAb, 7G3.33 This MoAb is able to bind to IL-3Rα and can neutralize both binding and biological activity. This MoAb was unable to bind to the N-terminally truncated receptor, as determined by fluorescent staining or Western blotting. When we tested this antibody for neutralization of proliferation of FDC-P1 cells expressing either IL-3Rα or IL-3RαΔNT and hβc, we found that the MoAb only neutralized IL-3–dependent proliferation from the wild-type receptor complex. This confirms that MoAb 7G3 does not bind to IL-3RαΔNT and indicates that the epitope for the 7G3 MoAb lies at least in part within the N-terminal domain of the receptor. The epitope may not be exclusively in this region, since a discontinuous epitope could be recognized. The simplest interpretation of these results is that the N-terminal domain is folded back to lie close to the IL-3 binding pocket formed between the two domains of the CRM (as suggested in Fig 10), and makes some direct contact(s) with IL-3. The contribution of the equivalent N-terminal domain of the IL-5 receptor α chain to the function of the IL-5 receptor has recently been reported,50 where species specificity of the receptor was found to be determined by residues in the N-terminal domain. Furthermore, deletion of the N-terminal region of this receptor resulted in complete loss of ligand binding.51 These data suggest that the N-terminal domain of the IL-5 receptor also plays a critical role in ligand binding.

A model for the contribution of the N-terminal domain of the IL-3Rα to ligand binding pocket based on the experimental observations presented here. We propose that the N-terminal domain is folded over so that it lies in close proximity to the hβc and predicted ligand binding region and that the cytoplasmic domain is essential for receptor phosphorylation and STAT activation.

A model for the contribution of the N-terminal domain of the IL-3Rα to ligand binding pocket based on the experimental observations presented here. We propose that the N-terminal domain is folded over so that it lies in close proximity to the hβc and predicted ligand binding region and that the cytoplasmic domain is essential for receptor phosphorylation and STAT activation.

Tertiary structure can be highly conserved even when there is little primary sequence homology. For example, the short 4 helix bundle cytokines such as IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, and GM-CSF all share a common structural motif,2,52 and all interact with a receptor complex that is multimeric. The multimerization of these receptor chains is an important step in formation of the signaling complex, and in several cases, a dimerization event is required for signal transduction (eg, IL-6 receptor53,54 and EpoR55,56 ). It is interesting to observe that the N-terminal region of all three cytokine receptors in the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF subfamily contains an odd number of cysteine residues, such that a disulfide-linked interaction with other receptor chains could take place. There is also an odd number of Cys residues in the membrane distal domain of the IL-3Rα CRM, raising the possibility of an intramolecular disulfide bond forming, which could stabilize the ligand binding site. In contrast, it has been demonstrated that a ligand-induced, disulfide-linked complex can form between the α and β chains.41 Furthermore, disulfide formation may not be required for high-affinity binding, but may confer stability on the high-affinity complex, as the deletion of the N-terminus does not result in complete loss of function or binding. It is not yet clear which disulfide bonds occur.

The contribution of the N-terminal domain to IL-3 binding, combined with the loss of binding of the neutralizing MoAb 7G3 on deletion of the N-terminal domain, suggests that at least part of this domain lies in close proximity to, or forms a part of, the IL-3 binding site. However, it is clear that significant ligand binding interactions must also reside in the CRM, since ligand is still able to bind (with reduced affinity) to the N-terminally truncated receptor. We have performed site directed mutagenesis on several residues predicted to lie in exposed loops within the CRM and find several sites that contribute to ligand binding (Barry et al, manuscript in preparation).

Secondary structure predictions indicate that the N-terminal domain contains seven beta strands, indicating that they may adopt a fibronectin-like structure similar to that of the domains within the cytokine receptor modules. In Fig 10, we propose a model for the structure of the IL-3 receptor complex that incorporates these findings. In this model the N-terminal domain lies close to the ligand binding cleft, as suggested by the contribution of this domain to binding and the involvement of this domain in the epitope for the neutralizing MoAb 7G3. The N-terminal CRM of the β chain may also lie in close proximity to the ligand binding site and α chain, as suggested by our finding that a disulphide bond forms between the α and β chains upon IL-3 binding.41 We further propose that the N-terminal domain of all three cytokine receptors, IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF, plays a role in formation of the ligand binding pocket and may be important in formation of the stable high-affinity receptor complex. Site directed mutagenesis of this domain may further define the regions involved in formation of the ligand binding site.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Chris Bagley for valuable discussions, Mara Dottore for excellent assistance with setting up binding assays, and Tom Gonda for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funded in part by a program grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Address reprint requests to G.J. Goodall, PhD, Hanson Centre for Cancer Research, IMVS, Frome Rd, Adelaide, S.A. 5000, Australia.