Abstract

Most of the 39 members of the homeobox (HOX) gene family are believed to control blood cell development. HOXC4 and HOXC6 gene expression levels increase with differentiation of lymphoid cells. In contrast, HOXC5 is not expressed in the lymphoid lineage, but was found in lymphoid cell lines, representing the neoplastic equivalents of various differentiation stages of T and B lymphocytes. In the present study, we investigated the HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 gene expression pattern in 89 non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHLs) of different histologic subtypes and originating from different sites. Using RNA in situ hybridization and semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, we found expression of HOXC4 in 83 of 88 and HOXC6 in 77 of 88 NHLs and leukemias investigated. In contrast, HOXC5 expression was found in only 26 of 87 NHLs and appeared to be preferentially expressed by two specific subsets of lymphomas, ie, primary cutaneous anaplastic T-cell lymphomas (9 of 9) and extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (maltomas; 7 of 9). These results indicate that, in contrast to HOXC4 and HOXC6, HOXC5 shows a type- and site-restricted expression pattern in both T- and B-cell NHLs.

ACCUMULATING EVIDENCE suggests that homeobox (HOX) genes play an important role in the regulation of hematopoiesis.1,2 Several HOX genes are lineage-specifically expressed, indicating a role in the lineage commitment.3-6 From the HOXC cluster, HOXC4, HOXC6, HOXC8, and HOXC11 genes are expressed in lymphoid cells.7-9 Moreover, in lymphoid cells, a specific alternative transcript of HOXC4 was found.7

Modulation of HOX gene expression can cause phenotypic changes, including the adhesive properties between cells and their environment.10,11 Increasing evidence indicates that genes encoding adhesion molecules are targets of HOX gene encoded proteins (homeoproteins).12-15 Furthermore, it has been suggested that adhesion molecules on the membranes of lymphocytes direct the migration of lymphocytes to particular organs.16 17 Therefore, alteration of adhesion molecule expression by homeoproteins might influence the homing of lymphocytes to different body sites.

Recently, we have shown that the HOXC4 and HOXC6 genes are increasingly expressed with progression of lymphoid differentiation.9 In contrast, HOXC5 expression was absent in reactive lymph nodes and tonsils and in unstimulated and stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes and lymphoid leukemias. However, lymphoma-derived cell lines did show HOXC5 expression.9 In addition, analysis of primary cutaneous lymphomas showed a strong expression of HOXC5 mRNA only in CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL) of the T-cell type.18

Because it appeared that HOXC5 shows strong expression in a subset of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, ie, ALCL, and homeoproteins might influence homing of lymphocytes, the question arises as to whether HOXC5 expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is correlated with histologic subtype and/or sites of origin.

In this study, using RNA in situ hybridization (RISH) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), we investigated the expression of HOXC5 and also of its flanking genes on the chromosome, HOXC4 and HOXC6, in a large group of NHLs differing in histologic type and sites of origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissues. Routinely formalin- and sublimate-fixed specimens of 89 NHLs derived from different sites, ie, lymph nodes, skin, Waldeyer's ring and gut, were selected from the files of the Comprehensive Cancer Center Amsterdam (for T-cell lymphomas see Table 1 and for B-cell lymphomas see Table 2). Lymphomas were classified according to the Updated Kiel classification with some modifications according to the REAL (revised European-American lymphoma) classification. All but 3 primary cutaneous lymphomas (cases no. 19 and 31 in Table 1 and case no. 2 in Table 2) have been analyzed previously for HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression.18 One nodal ALCL is a relapse from a primary cutaneous CD30+ ALCL (case no. 39 in Table 1). Frozen material was available for RT-PCR from 12 of the 43 T-NHLs and from 17 of the 46 B-NHLs.

Control tissues included 1 thymus of a child (6 months of age), 8 hyperplastic tonsils, and 6 hyperplastic lymph nodes. Hyperplastic tonsils were immediately collected after surgery. The tonsils were cut and parts were fixed with formalin and embedded in paraffin, frozen in liquid-nitrogen, and used for lymphocyte isolation. For RT-PCR, snap-frozen material was available of 3 of 6 lymph nodes and of 1 thymus. Peripheral blood was obtained from 6 healthy volunteers. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected after centrifugation over a Ficoll density gradient, counted, and immediately used for RNA isolation.

RISH. A previously published nonradioactive protocol was used9,18,19 with minor modifications applied for the use of sublimate fixed tissue. Sublimate fixed tissue prehybridization treatments included a short rinse in 0.01 mol/L HCl, followed by digestion with 0.1% Pepsin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), which was dissolved and prewarmed in 0.01 mol/L HCl for 10 minutes at 37°C, instead of digestion with 10 μg/mL Proteinase K (Boerhinger Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). In 1 case (no. 36) of a nodal ALCL, a double staining for HOXC5 by RISH and CD30 by immunohistochemistry was performed. Indirect detection of RISH products using fluorescence-tyramine was followed by an indirect immunohistochemic method using streptavidin-cyanide 3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Labeled antisense and sense riboprobes specific for HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC68,20,21 were generated from clones in transcription vector pGEM-3 (Promega, Madison, WI) using digoxigenin-11-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim) and SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases (Promega).22 Probes were estimated on size and integrity and calibrated based on the number of incorporated digoxigenin-11-UTP molecules.23

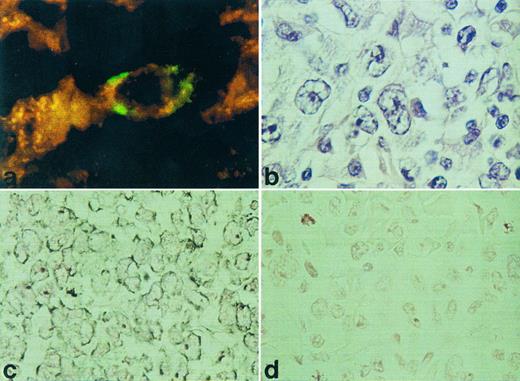

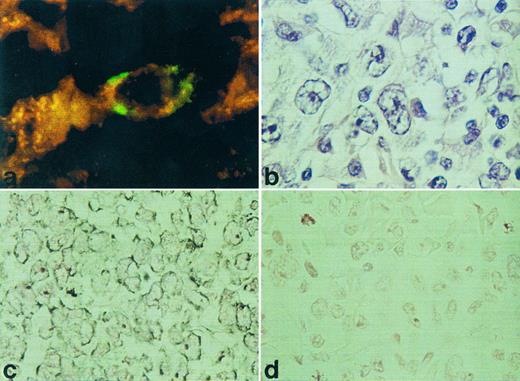

RISH analysis of HOXC5 on a nodal (a) and cutaneous (c) ALCL. A double staining for HOXC5 using RISH (green) and CD30 using immunohistochemistry (red) of a nodal ALCL (case no. 36) is shown in (a) and a hematoxlin and eosin staining of this lymphoma is shown in (b). Positive signals are shown as black DAB/Ni precipitates in (c), and sense control is shown in (d).

RISH analysis of HOXC5 on a nodal (a) and cutaneous (c) ALCL. A double staining for HOXC5 using RISH (green) and CD30 using immunohistochemistry (red) of a nodal ALCL (case no. 36) is shown in (a) and a hematoxlin and eosin staining of this lymphoma is shown in (b). Positive signals are shown as black DAB/Ni precipitates in (c), and sense control is shown in (d).

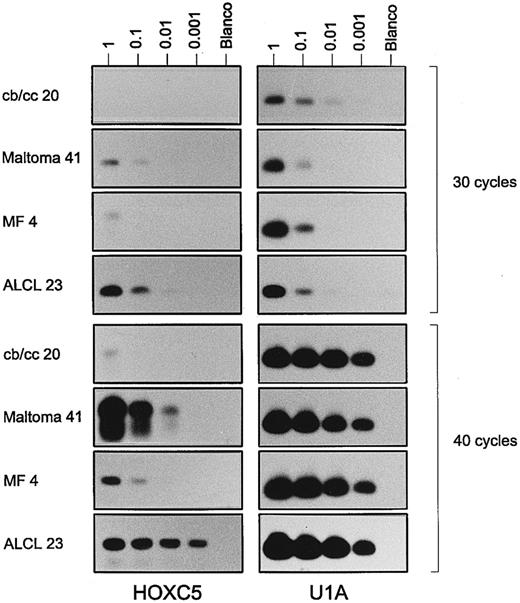

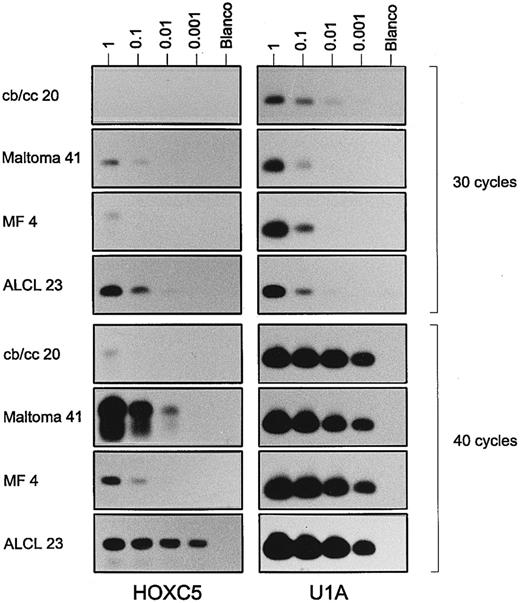

Results of a semiquantitative RT-PCR for HOXC5 (left panels) and control gene U1A (right panels) on a serial dilution of total RNA (1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 μg) from a centroblastic/centrocytic (cb/cc) lymphoma (case no. 20), a maltoma (case no. 41), an MF (case no. 4), and an ALCL (case no. 23). PCR results performing 30 cycles (upper panels) and 40 cycles (lower panels) are shown. Note that signals for HOXC5 in the maltoma and ALCL are visible after less PCR cycles and at higher dilutions than those in the cb/cc and the MF. Very weak bands for HOXC5 in the first dilution of cb/cc, the third dilution of maltoma after 30 cycles, and the fourth dilution of the maltoma after 40 cycles are not visible in the figure, but are present on the films.

Results of a semiquantitative RT-PCR for HOXC5 (left panels) and control gene U1A (right panels) on a serial dilution of total RNA (1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 μg) from a centroblastic/centrocytic (cb/cc) lymphoma (case no. 20), a maltoma (case no. 41), an MF (case no. 4), and an ALCL (case no. 23). PCR results performing 30 cycles (upper panels) and 40 cycles (lower panels) are shown. Note that signals for HOXC5 in the maltoma and ALCL are visible after less PCR cycles and at higher dilutions than those in the cb/cc and the MF. Very weak bands for HOXC5 in the first dilution of cb/cc, the third dilution of maltoma after 30 cycles, and the fourth dilution of the maltoma after 40 cycles are not visible in the figure, but are present on the films.

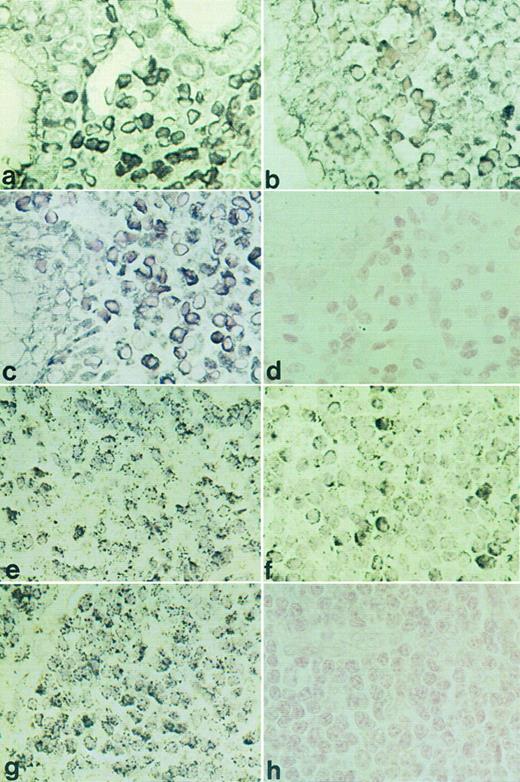

RISH analysis of HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 on a maltoma (a through d) and an immunocytoma (e through h). HOXC4 expression is shown in (a) and (e), HOXC5 in (b) and (f ), HOXC6 in (c) and (g), and sense control for HOXC5 in (d) and (h). Positive signals are shown as black DAB/Ni precipitates (a) or as black silver granules (e).

RISH analysis of HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 on a maltoma (a through d) and an immunocytoma (e through h). HOXC4 expression is shown in (a) and (e), HOXC5 in (b) and (f ), HOXC6 in (c) and (g), and sense control for HOXC5 in (d) and (h). Positive signals are shown as black DAB/Ni precipitates (a) or as black silver granules (e).

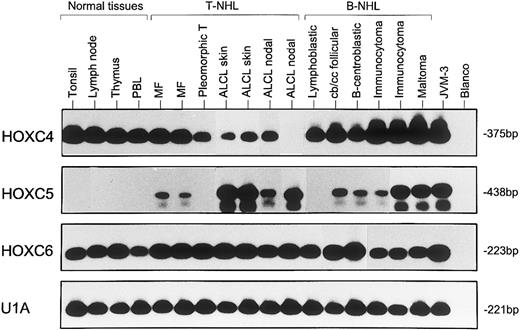

Representative results from two to five independent experiments of RT-PCR analysis showing expression of HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 in normal lymphoid tissues (lanes 1 through 4), T-NHL (lanes 5 through 11), and B-NHL (lanes 12 through 17). MF samples correspond with cases no. 1 and 4, pleomorphic T-cell lymphomas correspond with case no. 12, and ALCLs correspond with cases no. 39, 26, 30, and 32 of Table 1. B-NHLs correspond with cases no. 5, 19, 22, 35, 32, and 41 of Table 2. Controls included B-cell line JVM-3 and water (blanco). The snRNP gene U1A was used as control for the RNA quality and quantity. Blots hybridized with specific oligomer probes were exposed for 20 hours. Note that the immunocytoma in lane 16 (case no. 32), which is positive for HOXC5 expression by RISH analysis, shows a stronger signal for HOXC5 by RT-PCR than the RISH HOXC5-negative immunocytoma in lane 15 (case no. 35).

Representative results from two to five independent experiments of RT-PCR analysis showing expression of HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 in normal lymphoid tissues (lanes 1 through 4), T-NHL (lanes 5 through 11), and B-NHL (lanes 12 through 17). MF samples correspond with cases no. 1 and 4, pleomorphic T-cell lymphomas correspond with case no. 12, and ALCLs correspond with cases no. 39, 26, 30, and 32 of Table 1. B-NHLs correspond with cases no. 5, 19, 22, 35, 32, and 41 of Table 2. Controls included B-cell line JVM-3 and water (blanco). The snRNP gene U1A was used as control for the RNA quality and quantity. Blots hybridized with specific oligomer probes were exposed for 20 hours. Note that the immunocytoma in lane 16 (case no. 32), which is positive for HOXC5 expression by RISH analysis, shows a stronger signal for HOXC5 by RT-PCR than the RISH HOXC5-negative immunocytoma in lane 15 (case no. 35).

Controls included hybridization with a sense probe and hybridization without probe. Additionally, several specimens were incubated with 1.2 mg/mL RNase A (Promega) proteinase K digestion to determine the RNA origin of the signal. RNA quality of the sections was checked with a probe for human elongation factor-1α (hEF-1α)24 or β2 microglobulin (β2m). Sections lacking or showing very weak expression of hEF-1α or β2m were not included in the study.

RT-PCR. RT-PCR for HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 was performed as described previously.9,19 Briefly, total RNA was isolated from tonsillar lymphocytes and from 10 serial cryostat sections of frozen specimens of reactive lymph nodes, thymus, and lymphomas using the RNAzol B method. To avoid the possible amplification of HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 mRNA of epidermal cells in cutaneous lymphomas, the epidermis was removed by cutting it from the dermis. This was confirmed by light microscopy in the first and last hematoxylin eosin stained section of the lesion. Primers and oligonucleotide probes (Perkin Elmer, Oudekerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands) specific for the respective PCR product, spanning an intron,25,26 were designed with the PCRPLAN program of the PC/Gene software (IntelliGenetics, Mountain View, CA; for sequences, see Bijl et al9 ).

cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA and subsequently amplified for 40 cycles at 60°C annealing temperature (GeneAmp PCR system 9600; Perkin Elmer, Branchburg, NJ). Amplification products were hybridized with 32P-labeled internal oligonucleotide probes, usually with a specific activity of 0.8 to 2 × 107 and diluted in prehybridization mix to 105 cpm/mL. Exposure time of membranes to a film was standardized to 20 hours. Samples containing distilled water and samples without reverse transcriptase enzyme were included as negative controls. RT-PCR for housekeeping gene snRNP U1A9,27 was performed to assess the quality of the mRNA. Samples with very low or absent expression of mRNA transcripts from the gene snRNP U1A were excluded from the study. In addition, all lymphomas also showed clearly visible 28S and 16S ribosomal bands at the gel level,28 indicating a good RNA quality of the samples analyzed. B-cell line JVM-3 was used as positive control for HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression.

To perform a semiquantitative expression analysis, 4 samples of a 1:10 serial dilution of total RNA were transcribed to cDNA using the antisense primer for HOXC5 together with the antisense primer of U1A. Subsequently, PCR was performed for 25, 30, 35, or 40 cycles.

Interpretation of results. Expression analysis showed that representative sections of lymphomas appeared to be positive for HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression by both RISH and RT-PCR, or only by RT-PCR, or negative using both techniques. Neoplastic cells of lymphomas were considered to express HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 when both RT-PCR and RISH results were positive. Because infiltrating lymphocytes have been repeatedly shown to lack HOXC5 mRNA expression,9 lymphomas that were RT-PCR positive and RISH negative for HOXC5 were considered to express low levels of HOXC5 mRNA. When HOXC4 and HOXC6 expression was only detected by RT-PCR and not by RISH, the neoplastic cells were considered to lack expression or to express very low levels of HOXC4 and HOXC6, because infiltrating reactive lymphoid cells are known to express HOXC4 and HOXC6.9

Statistical analysis. Comparisons of HOXC5 expression in lymphomas according to histologic type and in site of origin were performed using the Fisher exact test. All P values are based on two-tailed statistical analysis. P values less than .05 are considered significant. Analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression in various types of T-NHL. Using RISH, HOXC5 expression was found in 14 of 40 T-NHL and was restricted to ALCLs (12 of 17) and pleomorphic medium and large T-cell lymphomas (2 of 13; Table 1). All small T-cell lymphomas (mycosis fungoids [MF] and small pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma) did not show expression of HOXC5. Statistical analysis showed that HOXC5 expression was correlated with ALCL (P < .001; Table 3). Hybridization signals were mainly located in the cytoplasm, but some cases showed additional staining of nucleoli (Fig 1). When present, epithelial cells of skin and gut also showed HOXC5 expression. To confirm that CD30+ anaplastic cells show HOXC5 expression, double stainings of RISH (HOXC5) and immunohistochemistry (CD30) were performed on a CD30+ ALCL (case no. 36 in Table 1). The anaplastic cells showed coexpression of the CD30 protein and HOXC5 mRNA (Fig 1a).

Of the 11 T-NHL tested for HOXC5 by RT-PCR, 9 showed HOXC5 expression. Five of these cases also showed HOXC5 expression by RISH. In 3 cases of MF, which did not show HOXC5 expression by RISH, HOXC5 expression was found by RT-PCR, suggesting very low levels of HOXC5 expression. In 1 case (no. 32), RT-PCR data could not be compared with RISH data.

To confirm that lymphomas expressing HOXC5 both by RISH and RT-PCR expressed higher levels of HOXC5 than lymphomas showing HOXC5 expression only by RT-PCR, a semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed on 2 RISH HOXC5-positive ALCLs (cases no. 23 and 30) and 2 RISH HOXC5-negative, RT-PCR HOXC5-positive MF (cases no. 1 and 4; see Fig 2). In primary cutaneous ALCLs, RT-PCR signals for HOXC5 mRNA were already detectable after performing 25 cycles of PCR (data not shown), whereas in MF, signals were only detectable after 30 cycles (Fig 2). Furthermore, signals for HOXC5 expression were detectable in 100× higher dilutions of RNA from cutaneous ALCLs than from MF.

Analysis of HOXC5 expression in relation to the site of origin of the T-cell lymphomas showed that 9 of the 14 HOXC5 RISH-positive T-cell lymphomas were derived from the skin, 2 from the gastrointestinal tract, and 3 from the lymph node (Table 3). All of these skin lymphomas were primary cutaneous ALCLs. The expression of HOXC5 in all cutaneous lymphomas did not differ from those originating from other sites (P = .101). However, HOXC5 expression was significantly associated with primary cutaneous ALCLs as compared with all other T-NHL originating from different sites (P < .001; Table 3). In contrast to the cutaneous ALCLs, HOXC5 expression was only detected in 3 of 8 nodal ALCLs. Moreover, 1 of these 3 nodal lymphomas was a nodal relapse from a primary cutaneous CD30+ ALCL. Comparison of the HOXC5 expression in cutaneous and nodal ALCLs showed that HOXC5 expression was significantly associated with cutaneous origin (P = .009). These results indicate that, in addition to histologic type, the site of origin of ALCL is also associated to HOXC5 expression.

HOXC4 expression in the tumor cells was shown in 39 of 43 and HOXC6 in 41 of 43 T-NHL by RISH (Table 1). Reactive lymphocytes and, when present, epithelial cells did show HOXC4 and HOXC6 expression. RT-PCR analysis showed HOXC4 and HOXC6 expression in 10 of 11 tested T-NHLs. The lymphomas lacking HOXC4 or HOXC6 mRNA expression by RT-PCR were cases that also were negative by RISH.

HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression in various types of B-NHL. RISH analysis showed that HOXC5 mRNA expression was present in 12 of 45 B-cell lymphomas, including maltomas (7 of 9), lymphoplasmacytic immunocytomas (2 of 6), centroblastic lymphomas (2 of 7), and an immunoblastic lymphoma (1 of 3; Table 2). Statistical analysis showed that HOXC5 expression was associated with B-cell lymphomas with plasmacytic differentiation (9 of 12), ie, maltomas (77%) and immunocytomas (22%), compared with other B-NHL (P = .001; Table 3). All small B-cell lymphomas without plasmacytic differentiation lacked HOXC5 expression. Representative examples of HOXC5 expression in a maltoma and a lymphoplasmacytic immunocytoma are shown in Fig 3b and f.

RT-PCR showed HOXC5 expression in 15 of 17 B-NHLs tested (Fig 4 and Table 2). In 7 cases (5 were HOXC5-positive and 2 HOXC5-negative), the RISH results were identical to the RT-PCR results. In 8 lymphomas in which no HOXC5 expression was found by RISH, RT-PCR was positive for HOXC5, indicating low levels of HOXC5 expression (Table 2). These lymphomas included a mantle cell lymphoma, 2 follicular and 2 diffuse centroblastic/centrocytic lymphomas, and 3 immunocytomas.

To confirm that RISH HOXC5-positive B-cell lymphomas also expressed higher levels of HOXC5 than RISH HOXC5-negative and RT-PCR HOXC5-positive lymphomas, a semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed on a maltoma (case no. 41 in Table 2) and a centroblastic/centrocytic lymphoma (case no. 20 in Table 2). Signals of HOXC5 expression were detectable in the maltoma after 30 cycles in the three lowest dilutions and only very weakly detectable in one dilution in the centroblastic/centrocytic lymphoma (Fig 2). HOXC5 signals were detectable in 100× higher dilutions of RNA from a HOXC5 RISH-positive maltoma than of a HOXC5 RISH-negative and HOXC5 RT-PCR–positive centroblastic/centrocytic lymphoma.

When the relationship between HOXC5 expression and site of origin of B-cell lymphomas was studied, 8 of the 12 RISH HOXC5-positive lymphomas appeared to be derived from the oro-digestive tract (Table 3). Six of these 8 lymphomas were maltomas, 1 was an immunoblastic lymphoma, and 1 was a centroblastic lymphoma. Statistical analysis showed that HOXC5 expression was significantly associated with lymphomas originating from the oro-digestive tract as compared with lymphomas originating from other body sites (P = .014). Furthermore, HOXC5 expression was clearly associated with maltomas as compared with all other B-NHLs originating from different sites (P < .001). However, when HOXC5 expression in lymphomas with lymphoplasmacytic differentiation derived from the oro-digestive tract (ie, maltomas) was compared with nodal immunocytomas, no statistical differences were found (P = .3). No RISH HOXC5-positive B-cell lymphomas of the skin were found.

Using RISH, mRNA expression of HOXC4 and HOXC6 was found in the tumor cells of nearly all B-NHLs (44 of 45 and 37 of 45 B-NHL, respectively; Table 2). Remarkably, all B-CLLs (5 of 5) were negative for HOXC6 by RISH. Only a few reactive positive cells were seen in the sections. RT-PCR analysis showed HOXC4 expression in all and HOXC6 expression in 15 of 17 tested B-NHLs (Fig 4 and Table 2). There was no relationship between HOXC4 or HOXC6 expression and the site of origin of a lymphoma (Table 3).

HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6 expression in normal lymphoid tissues. Using RISH, no HOXC5 mRNA transcripts were detected in B and T cells of hyperplastic tonsils, lymph nodes, and thymus. In contrast, lymphocytes of these tissues showed expression of HOXC4 and HOXC6 mRNA. Overlying epithelium of the tonsil was positive for all three HOX genes and served as an internal positive control.

Moreover, HOXC5 expression was not detected in normal lymphocytes using RT-PCR (Fig 4), whereas RT-PCR products of HOXC4 and HOXC6 were generated from lymph nodes, thymus, and isolated lymphocytes of tonsils and peripheral blood, thus confirming RISH results.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a differential expression of HOXC5 was found in T-NHLs and B-NHLs. In T-NHL, HOXC5 was preferentially expressed in ALCLs (12 of 17). Only two pleomorphic medium/large T-cell lymphomas expressed HOXC5 mRNA (2 of 13). No HOXC5 mRNA was detected in 8 small T-cell lymphomas. From the observation that HOXC5 was expressed by all 9 cutaneous, but only by 3 of the 8 nodal large T-cell lymphomas, it can be concluded that this expression of HOXC5 is related to primary cutaneous and not to primary node-based ALCL. Moreover, 1 of the 3 nodal ALCLs, which was found to express HOXC5 by RISH, appeared to be a relapse of a primary cutaneous CD30+ ALCL (case no. 39), further suggesting a relationship between HOXC5 expression and skin localization. Unfortunately, no tissue of this primary cutaneous lymphoma was available to test HOXC5 gene expression. Furthermore, the expression of HOXC5 preferentially in primary cutaneous ALCL supports the notion that primary cutaneous and primary nodal ALCL are different clinicopathologic entities in terms of clinical behavior and molecular genetics.29

In the group of B-NHLs, we observed that HOXC5 mRNA expression was strongly associated to lymphomas with lymphoplasmacytic differentiation (9 of 15). Only 3 other B-cell lymphomas, including 2 centroblastic and 1 immunoblastic lymphoma, showed HOXC5 mRNA transcripts. Remarkably, most of these HOXC5-positive lymphomas (6 of 9) were derived from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue located along the oro-gastrointestinal tract (maltomas). Interestingly, the oro-digestive tract localization of a lymphoma was also associated with HOXC5 expression irrespective of its histologic type. In the group of lymphomas with lymphoplasmacytic differentiation, no preference of HOXC5 expression for an oro-digestive tract or lymph node origin was found (Table 3), indicating that HOXC5 expression in those lymphomas is more associated with histologic type than with body site origin. All small B-cell lymphomas, without plasmacytic differentiation, lacked strong HOXC5 expression, as found by RISH.

Overexpression of HOXC5 might be caused by amplifications or translocations involving the HOXC5 coding region or deregulation of gene expression. Although the precise location is not known for HOXC5, the complete HOXC cluster is designated to 12q13.3.30 Amplifications or translocations involving the HOXC cluster have to our knowledge not been described for lymphomas, and neither deregulation of HOXC gene expression has been reported in lymphomas. It might be useful to investigate this region more clearly in primary cutaneous ALCL and maltomas.

The preferential expression of HOXC5 in primary cutaneous ALCL and maltomas indicates that HOXC5 is site and type specifically expressed in NHLs. Together with the absence of HOXC5 expression in reactive skin infiltrates,18 in hyperplastic lymph nodes and tonsils,9 and in unstimulated and stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes,18 the expression pattern of HOXC5 strongly suggests that HOXC5 is involved in the pathogenesis of these lymphomas.

Furthermore, we have shown that HOXC4 and HOXC6 mRNA is found in 93% and 90% of all lymphomas tested, respectively. This is in agreement with earlier findings that HOXC4 and HOXC6 are expressed during normal lymphoid differentiation and are found in lymphoid cell lines of different maturation stages.9 Interestingly, HOXC6 mRNA expression was never found in the 5 B-CLLs tested. However, HOXC6 mRNA was found in germinal center B cells, follicle center cell lymphomas, and lymphomas with plasmacytic differentiation. Therefore, the absence of HOXC6 expression in B-CLL might be related to the incapability of the neoplastic cells to differentiate into plasma cells.

Our observation that HOXC5 is preferentially expressed in certain types of mature lymphomas originating from specific sites, ie, ALCL of the skin and maltomas, confirms a temporal as well as a positional dependent expression of HOXC5, similar to the expression of HOX genes as found during embryonic development. In the embryo, the homeotic network functions as a biologic clock, activating (groups of ) cells along the anterior-posterior axis to morphologic changes or migration at restricted time points in the development. Effector genes that can fulfill these functions and have been shown to be target genes of homeoproteins include genes that encode morphoregulatory proteins (including adhesion molecules),15,31 cytokines, growth factors, and homeoproteins themselves.25,32,33 In this respect, it is noteworthy that primary cutaneous ALCLs and maltomas express site-specific adhesion molecules involved in homing of lymphoid cells to specific body sites, ie, the cutaneous lymphocyte antigen for homing to the skin16,17,34 and the α4β7 integrin for homing to the gastrointestinal tract.16,17 35 Transfection of HOXC5 constructs in cell lines, enabling modulation of HOXC5 overexpression, are currently performed to elucidate whether homeoproteins of HOXC5 are capable of inducing the expression of these adhesion molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Prof Dr E. Boncinelli for providing the cDNA clones for the homeobox gene probes. Dr J. Middeldorp, Dr M. Jiwa, Dr G. Sauvageau, and W. Vos have contributed to this work by their stimulating discussions and advice.

Supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant No. IKA 90-17).

Address reprint requests to Chris J.L.M. Meijer, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Vrije Universiteit Hospital, De Boelelaan 1117, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands.